Abstract

Metal complexes bearing dichalcogenated imidodiphosphinate [R2P(E)NP(E)R2′]− ligands (E = O, S, Se, Te), which act as (E,E) chelates, exhibit a remarkable variety of three-dimensional structures. A series of such complexes, namely, square-planar [Cu{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}2], tetrahedral [Zn{(EPPh2)(EPPh2)N-E,E}2], E = O, S, and octahedral [Ga{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O,O}3], were tested as potential inhibitors of either the platelet activating factor (PAF)- or thrombin-induced aggregation in both washed rabbit platelets and rabbit platelet rich plasma. For comparison, square-planar [Ni{(Ph2P)2N-S-CHMePh-P, P}X2], X = Cl, Br, the corresponding metal salts of all complexes and the (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand were also investigated. Ga(O,O)3 showed the highest anti-PAF activity but did not inhibit the thrombin-related pathway, whereas Zn(S,S)2, with also a significant PAF inhibitory effect, exhibited the highest thrombin-related inhibition. Zn(O,O)2 and Cu(O,O)2 inhibited moderately both PAF and thrombin, being more effective towards PAF. This work shows that the PAF-inhibitory action depends on the structure of the complexes studied, with the bulkier Ga(O,O)3 being the most efficient and selective inhibitor.

1. Introduction

Extensive research work over the last few years has revealed a remarkable structural variability of transition metal compounds bearing dichalcogenated imidodiphosphinate type of ligands, that is, [R2P(E)NP(E)R2′]−, E = O, S, Se, Te; R, R′ = various aryl or alkyl groups. These ligands have been shown to display great coordinating versatility, producing both single and multinuclear metal complexes, with a variety of bonding modes [1–3]. The coordinating flexibility of these (E,E) chelating ligands is attributed, mainly, to their large (c a. 4 Å) E⋯E bite, which would accommodate a range of coordination sphere geometries. For instance, it was recently shown that the [iPr2P(Se)NP(Se)iPr2]− ligand affords both tetrahedral and square-planar complexes of Ni(II) [4], in agreement with an earlier observation on the analogous [Ph2P(S)NP(S)Ph2]− ligand [5]. Moreover, the nature of the R and R′ peripheral groups of the [R2P(S)NP(S)R2′]− ligand has been shown to affect the geometry of the complexes formed upon its coordination to Ni(II) [6, 7]. In a more general sense, depending on the nature of the metal ion, the chalcogen E atom and the R peripheral group, complexes bearing the above type of ligands were shown to contain rather diverse coordination spheres [8]. Such structural differences are of significant importance, as they are expected to lead not only to different stereochemical characteristics, but also to varied electronic properties of the metal site, which, in turn, could potentially result in significant biological reactivity [9].

The aim of this work was to investigate a series of structurally diverse metal coordination compounds bearing dichalcogenated imidodiphospinate ligands, as potential inhibitors of PAF (1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine). PAF is a phospholipid signalling molecule of the immune system and a significant mediator of inflammation. PAF transmits outside-in signals to intracellular transduction systems in a variety of cell types, including key cells of the innate immune and haemostatic systems, such as neutrophiles, monocytes, and platelets [10, 11]. In addition, it exhibits biological activity through specific membrane PAF-receptors, coupled with G-proteins. The binding of PAF on its receptor induces intracellular signaling pathways that lead to several cellular activation mechanisms, depending on the cell or tissue type [12]. It is well established that increased PAF-levels in blood or tissues lead to various inflammatory manifestations [10–12] such as cardiovascular, renal and periodontal diseases [13–16], allergy [17], diabetes [18], cancer [19] and AIDS [20].

A great variety of chemical compounds, both natural and synthetic, have demonstrated an inhibitory effect towards the PAF-induced biological activities, acting either through direct antagonistic/competitive effects by binding to the PAF-receptor, or through indirect mechanisms. In the latter case, the biofunctionality seems to correlate with changes in the membrane microenvironment of the PAF-receptor. Natural and synthetic PAF antagonists exhibit variable chemical structures that might lead to different pharmacological profiles. Since PAF is assumed to play a central role in many diseases, the effects of its antagonists have been widely studied in experimentally induced pathologies and in clinical studies [21–24].

The use of metal complexes as potential pharmaceutics is increasingly gaining ground [25, 26]. Particularly, complexes of Ga(III) bearing (O,O) chelating ligands have been studied thoroughly as promising nonplatinum compounds with superior anticancer activity and lower side effects [27, 28]. These complexes have also shown anti-inflammatory activity towards reumatoidis arthritis or Alzheimer's disease [25]. Cu(II) complexes have been investigated as anticancer agents, based on the assumption that endogenous metals may be less toxic [29]. In addition, Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes have been screened for their in vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity [30], whereas Zn(II) complexes have been investigated as agents against diabetes mellitus and ulcer [31]. A mechanistic understanding of how metal complexes exhibit their biological activity is crucial to their clinical success, as well as to the rational design of new compounds with improved pharmacological properties. In that respect, the in vitro investigation of novel metal complexes with targeted biomolecules may prove extremely valuable, before the in vivo tests in animal models.

In this study, we examined the in vitro effects of representative bis- or tris-chelated complexes of dichalcogenated imidodiphosphinate ligands, involving Cu(II), Zn(II) and Ga(III) centers, against PAF-induced biological activities. For this purpose, the potent inhibitory effect of these metal complexes was studied on PAF-induced platelet aggregation towards both washed rabbit platelets (WRPs) and rabbit platelet rich plasma (PRP). The complexes investigated contain diverse metal coordination spheres, exhibiting square-planar, tetrahedral and octahedral geometries. In addition, two square-planar complexes of Ni(II), bearing one bidentate diphosphinoamine ligand [32] and two halide ions were also investigated, with a view of revealing the necessary structural features, among this set of coordination compounds, that would ensure efficient and selective inhibition of PAF. Moreover, the inhibitory action of some of these complexes towards thrombin was also investigated, in order to probe their selectivity with respect to either the PAF- or the thrombin-dependent platelet aggregation.

2. Experimental Part

2.1. Materials and Methods

The following complexes were prepared according to published procedures: [Cu{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}2] [33], [Zn{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}2] [34], [Zn{(SPPh2)(SPPh2)N-S, S}2] [35], [Ga{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}3] [36], [Ni{(Ph2P)2N-S-CHMePh-P, P}Cl2] [37]. These complexes are abbreviated as Cu(O,O)2, Zn(O,O)2, Zn(S,S)2, Ga(O,O)3 and Ni(P,P)Cl2, respectively. The synthesis of the analogous to Ni(P,P)Cl2, bromide-containing Ni(P,P)Br2 complex, was carried out according to the published procedure [37], with the exception of using Ni(DME)Br2 (DME = 1,2-dimethoxyethane) as a starting material. The detailed synthesis and characterization of Ni(P,P)Br2 will be described elsewhere. The (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand was prepared as described in the literature [38]. The following metal salts, CuCl2, ZnCl2, Ga(NO3)3·9H2O and NiCl2·6H2O, were also tested for comparison purposes. All chemical reagents used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo, USA).

UV-vis spectra were recorded in a Varian Cary 3E spectrophotometer.

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), PAF (1-O-hexadecyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), thrombin and analytical solvents for the biological assays were purchased from Sigma.

Centrifugations were performed in a Heraeus Labofug 400R and a Sorvall RC-5B refrigerated super-speed centrifuge (Sigma-Aldrich). Aggregation studies were performed in a Chrono-Log aggregometer (model 400, Havertown, Pa, USA) coupled to a Chrono-Log recorder (Havertown) at 37°C with constant stirring at 1200 rpm.

2.2. Biological Assay on WRPs and Rabbit PRP

The potential inhibitory effect of a range of metal complexes towards PAF-related biological activities was estimated by biological assays based on WRPs aggregation [10]. The examined metal complexes were first dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), at an initial concentration of (4–8) × 10−3 M. Subsequently, different aliquots of the complexes' solutions were added in a BSA solution (2.5 mg BSA/mL of saline). PAF was also dissolved in the same BSA solution. The metal salts were dissolved in saline. The platelet aggregation induced by PAF (4.4 × 10−11 M final concentration in the aggregometer cuvette) or by thrombin (0.1 IU) on WRPs, was measured before (considered as 0% inhibition) and after the addition of the sample examined. A linear plot of inhibition percentage (ranging from 20% to 80%) versus the concentration of the sample was established for each metal complex. From this curve, the concentration of the sample that inhibited 50% of the PAF-induced aggregation (IC50) was calculated. Biological assays were performed several times (n > 3), according to methods of Demopoulos et al. [10] and Lazanas et al. [39], so as to ensure reproducibility. The same procedure was also followed in the case of rabbit PRP, as previously described [40].

2.3. Statistical Methods

All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The t-test was employed to assess differences among the IC50 values of each metal complex against either the PAF- or thrombin-induced aggregation. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when the statistical p value was smaller than 0.05. Data were analyzed using a statistical software package (SPSS for Windows, 16.0, 2007, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) and Microsoft Excel 2007.

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Structures and Stability of the Complexes

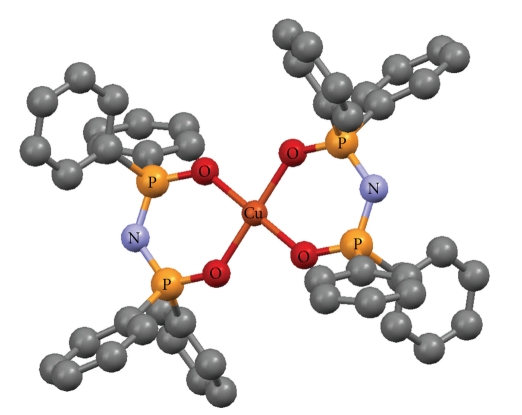

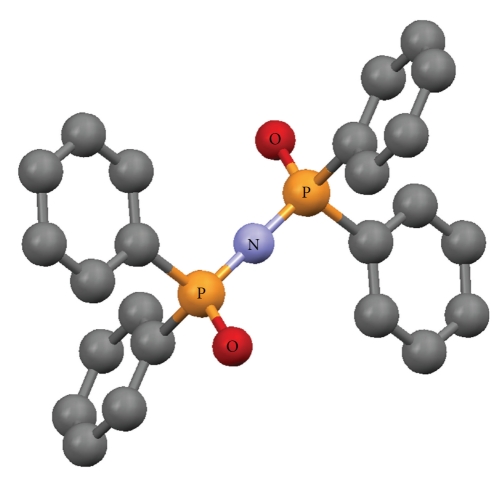

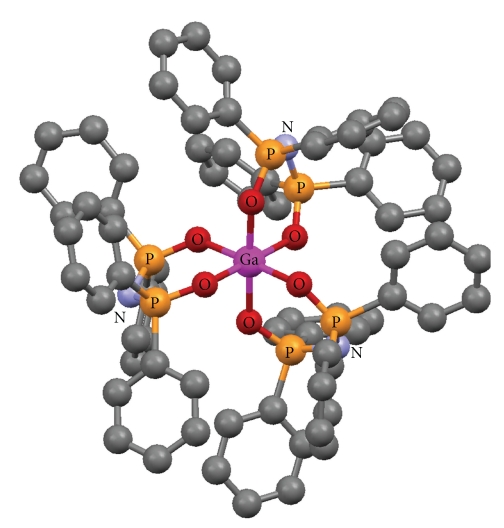

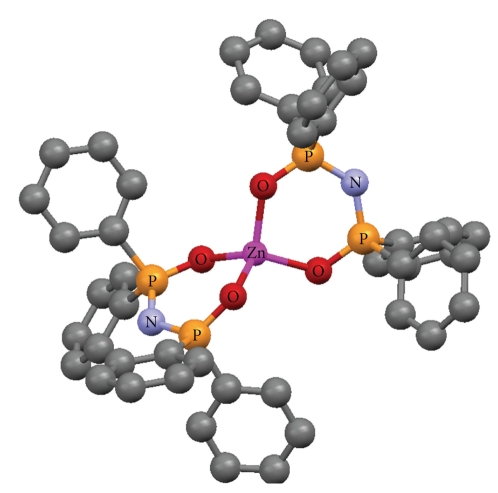

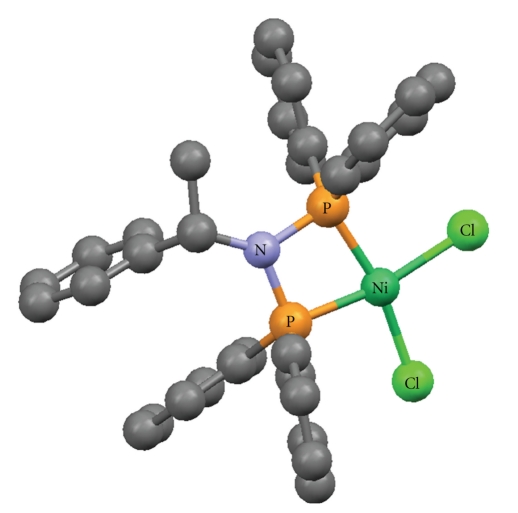

The crystallographic structures of Cu(O,O)2 [33], Zn(O,O)2 [34], Ga(O,O)3 [36] and Ni(P,P)Cl2 [37], as well as the (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand [41] have been already described (Figures 1–5). A variety of metal core geometries is demonstrated: Cu(O,O)2 and Ni(P,P)Cl2 are square-planar, whereas Zn(O,O)2 is tetrahedral and Ga(O,O)3 is octahedral. The Zn(S,S)2 and Ni(P,P)Br2 complexes are expected to be structurally similar to Zn(O,O)2 and Ni(P,P)Cl2, respectively. UV-vis absorption spectra of the light blue DMSO solutions of Cu(O,O)2 confirmed that the complex was stable for the time-span of the study. This is expected since Cu(O,O)2 and the rest of the dichalcogenated imidodiphosphinate complexes, contain highly stable six-membered M-E-P-N-P-E chelating rings [1, 2]. On the other hand, for Ni(P,P)2X2, X = Cl, Br, the intensity of the absorption maximum was gradually decreasing. Therefore, degradation of the complexes at some extent is likely, which is expected to affect their inhibitory action.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of [Cu{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}2] [33]. Color code: Cu (brown), O (red), P (orange), N (light blue), C (grey).

Figure 5.

Crystal structure of the (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand [41]. Color code: O (red), P (orange), N (light blue), C (grey).

3.2. Inhibitory Effect of Metal Complexes and Metal Salts towards the PAF-Induced WRP's Aggregation

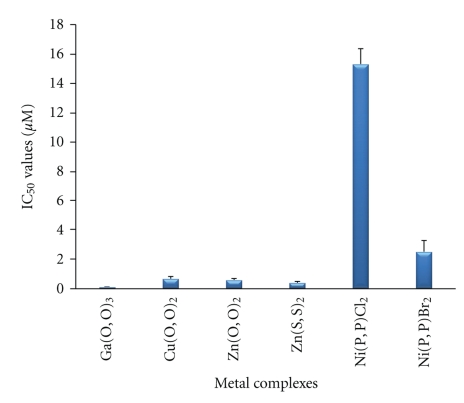

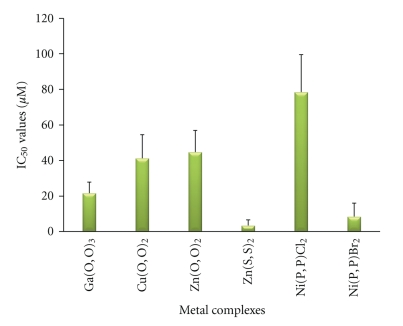

All metal complexes under investigation inhibited the PAF-induced aggregation of WRPs. This inhibitory effect was expressed by their IC50 value (Figure 6). Among the metal complexes tested, Ga(O,O)3 exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect towards the PAF-induced WRP's aggregation, with an IC50 value of 62.4 ± 45.0 nM, which is more than one order of magnitude lower compared to the IC50 value of the other complexes tested. The Cu(O,O)2, Zn(O,O)2 and Zn(S,S)2 complexes also exhibited a significant inhibitory effect, with IC50 values (300–600 μM) being more than one order of magnitude smaller compared to the value of the Ni(P,P)Cl2 and Ni(P,P)Br2 complexes.

Figure 6.

The inhibitory effect of metal complexes towards the PAF-induced WRP's aggregation.

In order to assess whether the observed inhibitory effect of the metal complexes was due to their properties—mainly their three-dimensional structure—we also tested the corresponding metal salts. All metal salts examined exhibited a weak inhibitory effect, with their IC50 values ranging between 0.1 and 1 mM (Figure 7), significantly lower than those of the corresponding metal complexes (p < 0.001) (Figure 6). Moreover, since Ga(O,O)3 showed the most prominent inhibitory effect, we also examined the corresponding (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand, which has already been structurally characterized [41]. This compound exhibited a significantly smaller inhibitory effect (two orders of magnitude) against PAF (IC50 = 1.57 ± 0.37 μM) compared with the Ga(O,O)3 complex (p < 0.001). This ligand's IC50 value is clearly smaller than those of the metal salts, but significantly greater than those of the Cu(O,O)2 and Zn(O,O)2 complexes (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

The inhibitory effect of metal salts towards the PAF-induced WRP's aggregation.

3.3. Inhibitory Effect of Metal Complexes and Metal Ions against the Thrombin-Induced WRP's Aggregation

The metal complexes exhibiting the stronger inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced WRP's aggregation were further tested for their potential inhibitory effect towards the thrombin-induced WRP's aggregation [10]. The data of Table 1 show that, among all complexes tested, Ga(O,O)3 did not inhibit thrombin, even at concentrations up to 10−4 M, while Zn(S,S)2 showed the strongest inhibitory effect, displaying an IC50 value at least one order of magnitude smaller than that of Cu(O,O)2 and Zn(O,O)2.

Table 1.

The inhibitory effect of metal complexes towards the thrombin-induced WRP's aggregation.

| Metal complex | IC50 value (μM) |

|---|---|

| Ga(O,O)3 | — |

| Cu(O,O)2 | 7.86 ± 4.77 |

| Zn(O,O)2 | 12.80 ± 5.62 |

| Zn(S,S)2 | 0.594 ± 0.41 |

3.4. Inhibitory Effect of Metal Complexes and Metal Ions against the PAF-Induced Rabbit PRP Aggregation

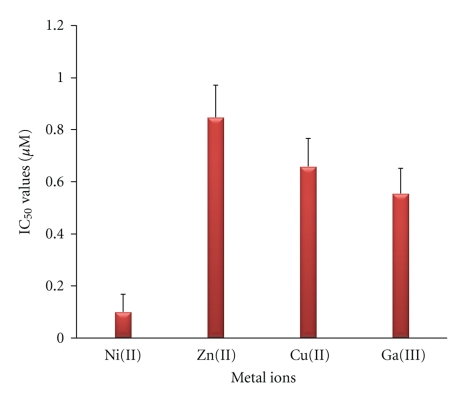

The metal complexes that inhibited the PAF-induced WRP's aggregation were further tested for their potential inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced rabbit PRP aggregation. All metal complexes indeed showed such inhibitory behavior, with IC50 values presented in Figure 8. The Ga(O,O)3, Zn(S,S)2 and Ni(P,P)Br2 complexes exhibited the highest inhibitory effect, since their IC50 values were significantly lower than that of all the other complexes tested (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

The inhibitory effect of metal complexes towards the PAF-induced rabbit PRP aggregation.

Moreover, we also tested the potential inhibitory effect of the corresponding metal salts. From all metal salts tested, only CuCl2 exhibited a weak inhibitory effect (IC50 = 12.3 ± 1.13 mM), three orders of magnitude larger than that of its corresponding Cu(O,O)2 complex (p < 0.001). On the contrary, the Ga(III), Ni(II) and Zn(II) salts did not inhibit the PAF-induced aggregation of rabbit PRP. Similarly, the (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand did not show such an inhibitory action.

4. Discussion

The successful application of several anti-PAF agents [11–24], and metal complexes [25–31] towards various inflammatory pathological situations, led us to study the effect of the metal complexes described above towards PAF-related biological activities. In that respect, we have primarily studied the in vitro effects of these compounds on the PAF-induced platelet aggregation. We have previously showed that cis-[RhL2Cl2]Cl, L = 2-(2'-pyridyl)quinoxaline, is a potent inhibitor of this type, having an IC50 value of 210 nM (at 0.02 nM PAF), with the inhibitory effect taking place, partly, through the PAF-receptor dependent way [42].

In this study, the biological assays were focused on the PAF-induced WRP's and rabbit PRP aggregation. In particular, our study on WRPs probes the anti-PAF activity of metal complexes under the experimental conditions applied, while, in the case of rabbit PRP, the conclusions drawn pinpoint the effect of these compounds towards the PAF activation at more similar to the in vivo conditions. Our work leads to the unprecedented conclusion that several metal complexes inhibited the PAF-induced aggregation towards both WRPs and rabbit PRP, in a dose-dependent manner. Significantly higher concentrations (at least one order of magnitude) of each compound were needed in order to inhibit the PAF-induced aggregation of rabbit PRP, compared to those needed in order to inhibit the corresponding aggregation of WRPs. The metal complexes with the most prominent anti-PAF activity were additionally tested towards the thrombin-induced aggregation of WRPs.

The IC50 values reflect the inhibition strength of each metal complex, since a low IC50 value reveals stronger inhibition of the PAF-induced aggregation for a given metal complex concentration. It is of significant importance that the IC50 values of these compounds (expressed as μM) against the PAF-induced aggregation are comparable with the IC50 values of some of the most potent PAF receptor antagonists, namely WEB2170, BN52021, and Rupatadine (0.02, 0.03 and 0.26 μM, resp.) [43–45]. This observation demonstrates that the metal complexes in question exhibit a strong inhibitory effect against the PAF activity. The octahedral Ga(O,O)3 complex, which contains the larger number (12) of phenyl rings in the second coordination sphere (Figure 3), is clearly the bulkier compared to the rest of the complexes studied (Figures 1, 2, and 4). This tris-chelated complex exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced aggregation of WRPs, with an IC50 value of 0.062 ± 0.045 μM. The fact that this complex did not inhibit the thrombin-induced aggregation of WRPs, even at high doses, suggests that it antagonizes the platelet aggregation through the selective inhibition of the PAF-receptor pathway. Moreover, since the complexes of Cu(II) (square planar) and Zn(II) (tetrahedral), bearing the same (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand, exhibited an appreciable but lower inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced aggregation of both WRPs and rabbit PRP compared to Ga(O,O)3, it is concluded that this action depends primarily on the complexes' three-dimensional structure. This proposal is also supported by the fact that the corresponding metal salts either inhibited weakly the PAF-induced WRP's aggregation, or showed no inhibitory action at all when tested in rabbit PRP. As far as the inhibitory effect of ZnCl2 is concerned, our results are consistent with those reported earlier [46].

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of [Ga{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}3] [36]. Color code: Ga (pink), O (red), P (orange), N (light blue), C (grey).

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of [Zn{(OPPh2)(OPPh2)N-O, O}2] [34]. Color code: Zn (pink), O (red), P (orange), N (light blue), C (grey).

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of [Ni{(Ph2P)2N-S-CHMePh-P, P}Cl2] [37]. Color code: Ni (green), Cl (light green), P (orange), N (light blue), C (grey).

It should be stressed that, even though the (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand (Figure 5) inhibited the PAF-induced aggregation of WRPs, this effect was significantly less prominent compared with the effects observed in the case of the metal complexes studied. In addition, this ligand did not influence the PAF-induced aggregation of rabbit PRP, a fact that confirms the importance of specific structural characteristics of the inhibitors. Moreover, it emphasizes that the coordination of metal ions to ligands, each separately showing some PAF-inhibitory action, enhances these inhibitory properties. Similar phenomena of pharmacological profile enhancement are also reported in the case of classic anti-inflammatory drugs like indomethacin, as well as antioxidants such as bioflavonoid rutin and naringin, coordinated to transition metals [47–50]. Similar behavior was also established in the case of Cu(II) and Pt(II) complexes with various ligands [25, 50–52].

Besides their anti-PAF activity, Cu(O,O)2 and Zn(O,O)2 inhibited also the thrombin-induced aggregation of WRPs, but at higher concentrations than those tested against PAF, suggesting that these metal complexes exhibit a more general anti-inflammatory action, which, however, is more specific towards the PAF-related pathway. As far the tetrahedral Zn(S,S)2 complex is concerned, it exhibited the highest inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced aggregation of rabbit PRP, even when compared with that of Ga(O,O)3. At the same time, this complex showed also a strong inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced aggregation of WRPs, which although lower than that of Ga(O,O)3, it is almost twice as strong (statistically borderline significant with p = 0.065) than that of Zn(O,O)2 and Cu(O,O)2. Also, this complex inhibited strongly the thrombin-induced aggregation of WRPs, at similar concentrations with those tested against PAF in WRPs, having an IC50 value at least one order of magnitude lower than those of Zn(O,O)2 and Cu(O,O)2. This result suggests that Zn(S,S)2 exhibits a more general anti-inflammatory activity, since it can equally inhibit both the PAF and thrombin-related activities. Taking also into account that in severe inflammatory procedures implicated in cancer situations like melanoma, the PAF- and thrombin-activated pathways are interrelated, thus regulating, for instance, both the melanoma cell adhesion and its metastasis [53, 54], compounds such as Zn(S,S)2, Zn(O,O)2 and Cu(O,O)2, with inhibitory effects towards both PAF and thrombin-related activities, are promising candidates as potential anticancer or antithrombotic agents.

Regarding the square-planar complexes of Ni(II) studied in this work, both Ni(P,P)Cl2 and Ni(P,P)Br2 only weakly inhibited the PAF-induced aggregation of WRPs compared with the imidodiphosphinate-containing complexes. The gradual degradation of these complexes in DMSO, documented by their UV-vis spectra, is the most likely explanation for this observation. However, the fact that, in the case of rabbit PRP, the Ni(P,P)Br2 complex exhibited a noticeable inhibitory effect against the PAF-induced aggregation, at levels comparable to those of Ga(O,O)3 and Zn(S,S)2 (Figure 8), shows that the integrity of its structure is sufficiently retained. The observed instability of Ni(P,P)X2, X = Cl, Br, in DMSO renders them unsuitable for inhibitory action, at least under the conditions employed in this work. Therefore, the thrombin-induced WRP's aggregation by these complexes was not investigated.

5. Conclusions

A series of metal complexes, bearing dichalcogenated imidodiphosphinate ligands, inhibited the PAF-induced aggregation of both WRPs and rabbit PRP, at concentrations comparable with those of classical PAF-inhibitors. The compounds with the stronger anti-PAF activities exhibited different specificity against the thrombin-induced platelet aggregation: Ga(O,O)3, with the highest anti-PAF activity, did not inhibit the thrombin-related pathway, whereas Zn(S,S)2, with also a strong inhibitory effect against PAF, exhibited the highest inhibition against thrombin. On the other hand, Zn(O,O)2 and Cu(O,O)2 inhibited moderately both PAF and thrombin, being more effective towards PAF. The metal salts and the (OPPh2)(OPPh2)NH ligand showed no appreciable anti-PAF or antithrombin activity. By comparing the relative inhibitory activities of all compounds studied, it is concluded that the biological activities of the metal complexes depend, at least in part, on their stereochemical properties. In this respect, the more spherical and bulky structure of Ga(O,O)3 seems to be the most suitable for a PAF-related inhibitory action. On the contrary, this complex is totally inactive towards the thrombin-related pathway. Whether this remarkable selectivity is indeed due to a more efficient interaction of Ga(O,O)3 with the PAF-receptor, remains to be investigated in future studies. It is of interest that similar tris-chelated Ga(III) complexes have shown significant pharmaceutical action towards various pathological cases [27, 28]. The exploration of additional complexes of variable metal ions and three-dimensional structures is clearly needed, in an effort to further elucidate the necessary electronic or structural features for a significant and selective PAF- or thrombin-related inhibitory function.

Acknowledgments

P. Kyritsis thanks the Special Account of the University of Athens (Grant 7575) and the Empirikion Foundation for funding, as well as Dr G. S. Papaefstathiou for a gift of Ga(NO3)3·9H2O. The referees of the manuscript are thanked for their constructive comments. This article is dedicated to Professor Nick Hadjiliadis, on the occasion of his retirement.

References

- 1.Silvestru C, Drake JE. Tetraorganodichalcogenoimidodiphosphorus acids and their main group metal derivatives. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2001;223(1):117–216. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haiduc I. Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II: From Biology to Nanotechnology. Vol. 1. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2003. Dichalcogenoimidodiphosphinato ligands; pp. 323–347. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chivers T, Konu J, Ritch JS, Copsey MC, Eisler DJ, Tuononen HM. New tellurium-containing ring systems. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2007;692(13):2658–2668. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levesanos N, Robertson SD, Maganas D, et al. Ni[(EPi Pr 2)2N]2 complexes: stereoisomers (E = Se) and square-planar coordination (E = Te) Inorganic Chemistry. 2008;47(8):2949–2951. doi: 10.1021/ic800272v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simón-Manso E, Valderrama M, Boys D. Synthesis and single-crystal characterization of the square planar complex [Ni{(SPPh2)2N-S,S′}2] · 2THF. Inorganic Chemistry. 2001;40(14):3647–3649. doi: 10.1021/ic001184l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rösler R, Silvestru C, Espinosa-Pérez G, Haiduc I, Cea-Olivares R. Tetrahedral versus square-planar NiS4 core in solid-state bis(dithioimidodiphosphinato)nickel(II) chelates. Crystal and molecular structures of Ni[(SPR2)(SPPh2)N]2(R = Ph, Me) Inorganica Chimica Acta. 1996;241(2):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maganas D, Grigoropoulos A, Staniland SS. Tetrahedral and square-planar Ni[(SPR2)2N]2 complexes, R = Ph&iPr revisited: experimental and theoretical analysis of interconversion pathways, structural preferences and spin delocalization. Inorganic Chemistry. 2010;49(11):5079–5093. doi: 10.1021/ic100163g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ly TQ, Woollins JD. Bidentate organophosphorus ligands formed via P-N bond formation: synthesis and coordination chemistry. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1998;176(1):451–481. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon EI, Szilagyi RK, DeBeer George S, Basumallick L. Electronic structures of metal sites in proteins and models: contributions to function in blue copper proteins. Chemical Reviews. 2004;104(2):419–458. doi: 10.1021/cr0206317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demopoulos CA, Pinckard RN, Hanahan DJ. Platelet-activating factor. Evidence for 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphorylcholine as the active component (a new class of lipid chemical mediators) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1979;254(19):9355–9358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Stafforini DM. The platelet-activating factor signaling system and its regulators in syndromes of inflammation and thrombosis. Critical Care Medicine. 2002;30(5):S294–S301. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM. Platelet-activating factor, a pleiotrophic mediator of physiological and pathological processes. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 2003;40(6):643–672. doi: 10.1080/714037693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montrucchio G, Alloatti G, Camussi G. Role of platelet-activating factor in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80(4):1669–1699. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demopoulos CA, Karantonis HC, Antonopoulou S. Platelet activating factor—a molecular link between atherosclerosis theories. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology. 2003;105(11):705–716. [Google Scholar]

- 15.López-Novoa JM. Potential role of platelet activating factor in acute renal failure. Kidney International. 1999;55(5):1672–1682. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McManus LM, Pinckard RN. PAF, a putative mediator of oral inflammation. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 2000;11(2):240–258. doi: 10.1177/10454411000110020701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasperska-Zajac A, Brzoza Z, Rogala B. Platelet-activating factor (PAF): a review of its role in asthma and clinical efficacy of PAF antagonists in the disease therapy. Recent Patents on Inflammation and Allergy Drug Discovery. 2008;2(1):72–76. doi: 10.2174/187221308783399306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathan N, Denizot Y, Huc MC, et al. Elevated levels of paf-acether in blood of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabete & Metabolisme. 1992;18(1):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsoupras AB, Iatrou C, Frangia C, Demopoulos CA. The implication of platelet activating factor in cancer growth and metastasis: potent beneficial role of PAF-inhibitors and antioxidants. Infectious Disorders—Drug Targets. 2009;9(4):390–399. doi: 10.2174/187152609788922555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsoupras AB, Chini M, Tsogas N, et al. Anti-platelet-activating factor effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a new insight in the drug therapy of HIV infection? AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2008;24(8):1079–1086. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Negro Álvarez JM, Miralles López JC, Ortiz Martínez JL, Abellán Alemán A A, Rubio Del Barrio R. Platelet-activating factor antagonists. Allergologia et Immunopathologia. 1997;25(5):249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desquand S. Effects of PAF antagonists in experimental models—possible therapeutic implications. Therapie. 1993;48(6):585–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koltai M, Hosford D, Guinot P, Esanu A, Braquet P. Platelet activating factor (PAF). A review of its effects, antagonists and possible future clinical implications. I. Drugs. 1991;42(1):9–29. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koltai M, Hosford D, Guinot P, Esanu A, Braquet P. PAF: a review of its effects, antagonists and possible future clinical implications. II. Drugs. 1991;42(2):174–204. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang CX, Lippard SJ. New metal complexes as potential therapeutics. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2003;7(4):481–489. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rijt SH, Sadler PJ. Current applications and future potential for bioinorganic chemistry in the development of anticancer drugs. Drug Discovery Today. 2009;14:1089–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timerbaev R. Advances in developing tris(8-quinolinolato)gallium(III) as an anticancer drug: critical appraisal and prospects. Metallomics. 2009;1:193–198. doi: 10.1039/b902861g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakupec MA, Keppler BK. Gallium in cancer treatment. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;4(15):1575–1583. doi: 10.2174/1568026043387449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marzano C, Pellei M, Tisato F, Santini C. Copper complexes as anticancer agents. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;9(2):185–211. doi: 10.2174/187152009787313837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chohan ZH. Metal-based antibacterial and antifungal sulfonamides: synthesis, characterization, and biological properties. Transition Metal Chemistry. 2009;34(2):153–161. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurai H, Katoh A, Yoshikawa Y. Chemistry and biochemistry of insulin-mimetic vanadium and zinc complexes. Trial for treatment of diabetes mellitus. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 2006;79(11):1645–1664. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamalesh Babu RP, Krishnamurthy SS, Nethaji M. Short-bite chiral diphosphazanes derived from (S)-α-methyl benzyl amine and their Pd, Pt and Rh metal complexes. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1995;6(2):427–438. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silvestru A, Rotar A, Drake JE, et al. Synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and structural studies of new Cu(I) and Cu(II) complexes containing organophosphorus ligands, and crystal structures of (Ph3P)2Cu[S2PMe2], (Ph3P)2Cu[(OPPh2)2N], Cu[(OPPh2)2N]2, and Cu[(OPPh2)(SPPh2)N]2 . Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 2001;79:983–991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silvestru A, Ban D, Drake JE. Zinc(II) tetraorganodichalcogenoimidodiphosphinates. Crystal and molecular structure of Zn[(OPPh2)2N]2 . Revue Roumaine de Chimie. 2002;47(10-11):1077–1084. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davison A, Switkes ES. The stereochemistry of four-coordinate bis(imidodiphosphinato)metal(II) chelate complexes. Inorganic Chemistry. 1971;10(4):837–842. [Google Scholar]

- 36.García-Montalvo V, Cea-Olivares R, Williams DJ, Espinosa-Pérez G. Stereochemical consequences of the bismuth atom electron lone pair, a comparison between MX6E and MX6 systems. Crystal and molecular structures of tris[N-(P,P-diphenylphosphinoyl)-P,P-diphenylphosphinimidato]bismuth(III),[[Bi{(OPPh2)2N}3], -indium(III),[In{(OPPh2)2N}3] · C6H6, and -gallium(III), [Ga{(OPPh2)2N}3] · CH2Cl2 . Inorganic Chemistry. 1996;35(13):3948–3953. doi: 10.1021/ic9512082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vougioukalakis GC, Stamatopoulos I, Petzetakis N, et al. Controlled vinyl-type polymerization of norbornene with a nickel(II) diphosphinoamine/methylaluminoxane catalytic system. Journal of Polymer Science A. 2009;47(20):5241–5250. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang FT, Najdzionek J, Leneker KL, Wasserman H, Braitsch DM. Facile synthesis of imidotetraphenyldiphosphinic acids. Synthesis and Reactivity in Inorganic and Metal-Organic Chemistry. 1978;8:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazanas M, Demopoulos CA, Tournis S, Koussissis S, Labrakis-Lazanas K, Tsarouhas X. PAF of biological fluids in disease: I.V. Levels in blood in allergic reactions induced by drugs. Archives of Dermatological Research. 1988;280(2):124–126. doi: 10.1007/BF00417717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsoukatos D, Demopoulos CA, Tselepis AD, et al. Inhibition of cardiolipins of platelet-activating factor-induced rabbit platelet activation. Lipids. 1993;28(12):1119–1124. doi: 10.1007/BF02537080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noth H. Crystal and molecular-structure of imido-tetraphenyl-dithio-phosphinic acid and imido-tetraphenyl-diphosphinic acid. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B. 1982;37:1491–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philippopoulos AI, Tsantila N, Demopoulos CA, Raptopoulou CP, Likodimos V, Falaras P. Synthesis, characterization and crystal structure of the cis-[RhL2Cl2]Cl complex with the bifunctional ligand (L) 2-(2′-pyridyl)quinoxaline. Biological activity towards PAF (Platelet Activating Factor) induced platelet aggregation. Polyhedron. 2009;28(15):3310–3316. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heuer HO. Involvement of platelet-activating factor (PAF) in septic shock and priming as indicated by the effect of hetrazepinoic PAF antagonists. Lipids. 1991;26(12):1369–1373. doi: 10.1007/BF02536569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fletcher JR, DiSimone AG, Earnest MA. Platelet activating factor receptor antagonist improves survival and attenuates eicosanoid release in severe endotoxemia. Annals of Surgery. 1990;211(3):312–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izquierdo I, Merlos M, García-Rafanell J. Rupatadine: a new selective histamine H1 receptor and platelet-activating factor (PAF) antagonist. A review of pharmacological profile and clinical management of allergic rhinitis. Drugs of Today. 2003;39(6):451–468. doi: 10.1358/dot.2003.39.6.799450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huo Y, Ekholm J, Hanahan DJ. A preferential inhibition by Zn2+ on platelet activating factor- and thrombin-induced serotonin secretion from washed rabbit platelets. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1988;260(2):841–846. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afanas’ev IB, Ostrakhovitch EA, Mikhal’chik EV, Ibragimova GA, Korkina LG. Enhancement of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of bioflavonoid rutin by complexation with transition metals. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;61(6):677–684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dillon CT, Hambley TW, Kennedy BJ, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity, antiinflammatory activity, and superoxide dismutase activity of copper and zinc complexes of the antiinfiammatory drug indomethacin. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2003;16(1):28–37. doi: 10.1021/tx020078o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kovala-Demertzi D, Hadjipavlou-Litina D, Staninska M, Primikiri A, Kotoglou C, Demertzis MA. Anti-oxidant, in vitro, in vivo anti-inflammatory activity and antiproliferative activity of mefenamic acid and its metal complexes with manganese(II), cobalt(II), nickel(II), copper(II) and zinc(II) Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;24(3):742–752. doi: 10.1080/14756360802361589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohan G, Nagar R, Agarwal SC, Mehta KMA, Rao CS. Syntheses and anti-inflammatory activity of diphenylamine-2,2′-dicarboxylic acid and its metal complexes. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;20(1):55–60. doi: 10.1080/1475636042000206455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pereira RMS, Andrades NED, Paulino N, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a metal complex containing naringin and Cu, and its antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiinflammatory and tumor cell cytotoxicity. Molecules. 2007;12(7):1352–1366. doi: 10.3390/12071352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pontiki E, Hadjipavlou-Litina D, Chaviara AT. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of copper (II) Schiff mono-base and copper(II) Schiff base coordination compounds of dien with heterocyclic aldehydes and 2-amino-5-methyl-thiazole. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;23(6):1011–1017. doi: 10.1080/14756360701841251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melnikova VO, Balasubramanian K, Villares GJ, et al. Crosstalk between protease-activated receptor 1 and platelet-activating factor receptor regulates melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM/MUC18) expression and melanoma metastasis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(42):28845–28855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melnikova VO, Bar-Eli M. Inflammation and melanoma metastasis. Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research. 2009;22(3):257–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]