In longitudinal studies with active outcome surveillance, the 3-month risk of stroke after TIA is approximately 17%.1 Recent reports suggest that expedient management of TIA can reduce this risk by as much as 80%.2,3 For such a strategy to have a major impact on the burden of cerebrovascular disease in the general population, stroke with preceding TIA must be a relatively common occurrence. Using data from the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network (RCSN), we sought to ascertain the frequency, characteristics, and outcomes of acute stroke patients with a prior TIA.

Methods.

We prospectively identified consecutive patients with a final diagnosis of acute stroke admitted to 12 Ontario hospitals through data recorded in the RCSN (accrual interval July 1, 2003, to September 30, 2007). Chart validation studies have shown excellent agreement with the RCSN database, with duplicate data abstraction performed on a random sample of 10% of charts. Patients with in-hospital strokes (n = 78) or unknown final diagnosis (n = 615) were excluded. Further details regarding the RCSN have been published elsewhere.4,5

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study was approved by the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Research Ethics Board and the Privacy Office of the Canadian Stroke Network; the requirement for written informed consent from participants was waived under Ontario privacy legislation.

Results.

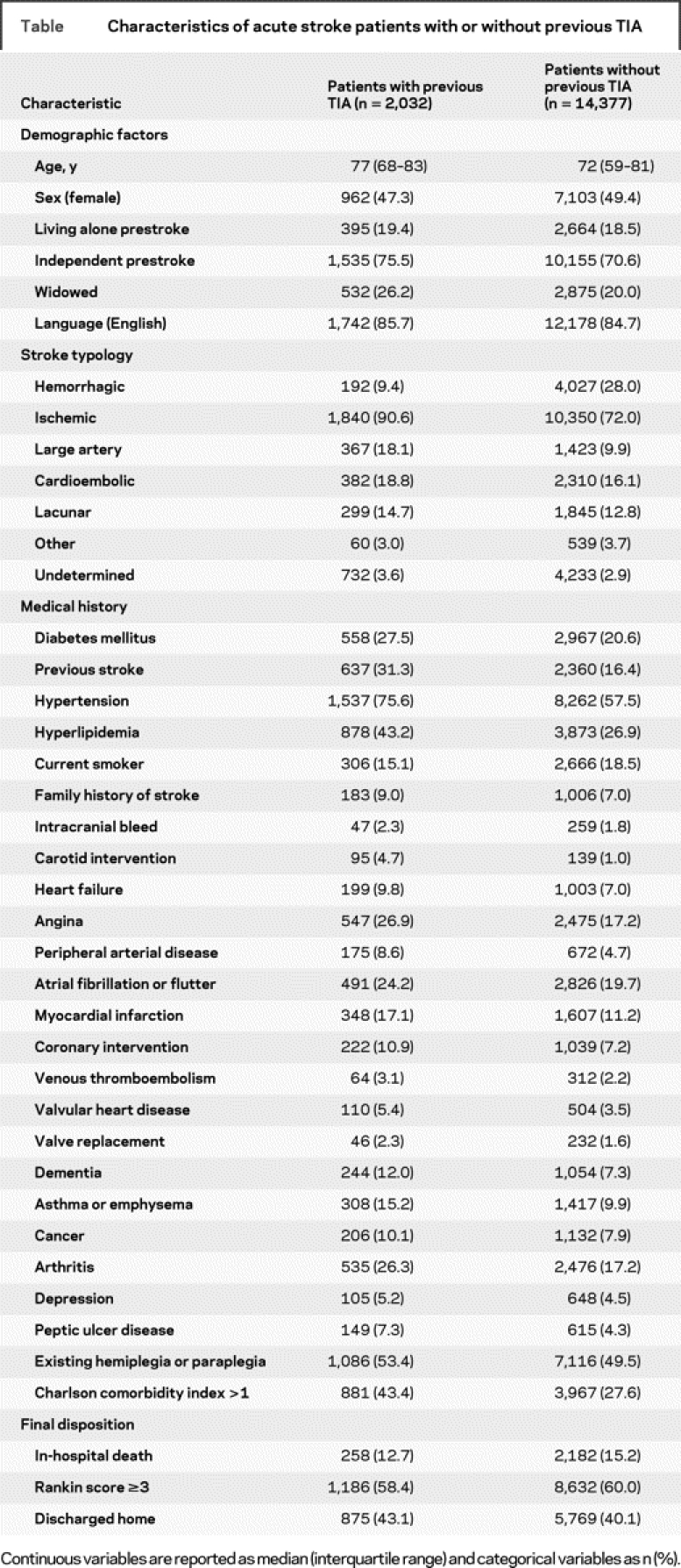

Of 16,409 consecutive patients with a final diagnosis of acute stroke in the RCSN, 2,032 (12.4%) had a prior TIA (ischemic neurologic deficit lasting less than 24 hours). Those with large artery ischemic stroke were most likely to have a previous TIA (20.5%), whereas patients with hemorrhagic stroke (4.6%) were least likely; 15.1% of ischemic stroke patients had a previous TIA. Patients with previous TIA were typically older than patients without previous TIA and more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, angina, peripheral arterial disease, and heart failure (table). Conversely, patients without prior TIA were significantly more likely to die during their hospital stay (15.2% vs 12.7%; p = 0.003), experience an in-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest (4.8% vs 3.1%; p < 0.001) or seizure (2.7% vs 1.5%; p = 0.002), and were less likely to be discharged to home (40.1% vs 43.1%; p = 0.012). After multivariable adjustment, lack of prior TIA continued to predict poor prognosis (for example, a 14% reduction in the odds of being discharged home, 95% confidence interval 5 to 22). These findings may be due to a lack of ischemic preconditioning in patients without prodromal TIA.6

Table Characteristics of acute stroke patients with or without previous TIA

Discussion.

A key limitation of our work is that we did not have information on the timing of prodromal TIA; however, previous data suggest that such events are most likely to occur within the week immediately preceding the stroke.7 In summary, only 1 in 8 patients with acute stroke had a previous TIA (with a higher frequency of TIA in large artery stroke). Widely implemented urgent TIA clinics might therefore prevent a small but significant fraction of the current stroke burden. In addition, these data highlight a need for risk profiles that accurately identify and stratify individual risk for first stroke.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by Julie T. Wang, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, Canada.

The study was sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network was sponsored by the Canadian Stroke Network and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Disclosure: Dr. Hackam, Dr. Kapral, Ms. Wang, and Dr. Fang report no disclosures. Dr. Hachinski serves as Editor-in-Chief of Stroke and has received honoraria for participation in symposia from Ferrer Group and Boehringer-Ingelheim.

Received March 9, 2009. Accepted in final form May 19, 2009.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Daniel G. Hackam, Stroke Prevention and Atherosclerosis Research Centre (SPARC), 1400 Western Road, London, Ontario, Canada N6G 2V2; dhackam@uwo.ca

&NA;

- 1.Wu CM, McLaughlin K, Lorenzetti DL, Hill MD, Manns BJ, Ghali WA. Early risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2417–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet 2007;370:1432–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavallee PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silver FL, Kapral MK, Lindsay MP, Tu JV, Richards JA. International experience in stroke registries: lessons learned in establishing the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:S235–S237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saposnik G, Hill MD, O’Donnell M, Fang J, Hachinski V, Kapral MK. Variables associated with 7-day, 30-day, and 1-year fatality after ischemic stroke. Stroke 2008;39:2318–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moncayo JM, de Freitas GRM, Bogousslavsky JM, Altieri MM, van Melle GP. Do transient ischemic attacks have a neuroprotective effect? Neurology 2000;54:2089–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: time window for prevention is very short. Neurology 2005;64:817–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]