Abstract

RNase BN, the Escherichia coli homolog of RNase Z, was previously shown to act as both a distributive exoribonuclease and an endoribonuclease on model RNA substrates and to be inhibited by the presence of a 3′-terminal CCA sequence. Here, we examined the mode of action of RNase BN on bacteriophage and bacterial tRNA precursors, particularly in light of a recent report suggesting that RNase BN removes CCA sequences (Takaku, H., and Nashimoto, M. (2008) Genes Cells 13, 1087–1097). We show that purified RNase BN can process both CCA-less and CCA-containing tRNA precursors. On CCA-less precursors, RNase BN cleaved endonucleolytically after the discriminator nucleotide to allow subsequent CCA addition. On CCA-containing precursors, RNase BN acted as either an exoribonuclease or endoribonuclease depending on the nature of the added divalent cation. Addition of Co2+ resulted in higher activity and predominantly exoribonucleolytic activity, whereas in the presence of Mg2+, RNase BN was primarily an endoribonuclease. In no case was any evidence obtained for removal of the CCA sequence. Certain tRNA precursors were extremely poor substrates under any conditions tested. These findings provide important information on the ability of RNase BN to process tRNA precursors and help explain the known physiological properties of this enzyme. In addition, they call into question the removal of CCA sequences by RNase BN.

Keywords: Nucleic Acid Enzymology, Ribonuclease, RNA, RNA Catalysis, Transfer RNA (tRNA), 3′-tRNase, CCA-containing tRNA Precursor, CCA-less tRNA Precursor, ElaC, tRNA 3′-End Maturation

Introduction

3′-Maturation of tRNA precursors differs among organisms depending on whether or not the universal 3′-terminal CCA sequence is encoded (1–6). In eukaryotic cells, this sequence is absent from tRNA precursors, and the 3′-processing step is catalyzed by the endoribonuclease, RNase Z or 3′-tRNase, which cleaves at the discriminator base to allow subsequent CCA addition by tRNA nucleotidyltransferase (3, 5, 7). In contrast, in some bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, the CCA sequence is encoded, and maturation of the 3′ terminus is carried out by exoribonucleases (8, 9), whereas in other organisms, such as Bacillus subtilis, both types of 3′-processing are operative (3). Surprisingly, in E. coli, despite the fact that the CCA sequence is present in all known tRNA precursors, an RNase Z homolog, termed RNase BN, is present (10). As a consequence, it has been of considerable interest to understand the function in E. coli of this apparently unnecessary enzyme.

RNase BN was originally discovered as an enzyme required for the maturation of those bacteriophage T4 precursor tRNAs that lack a CCA sequence (11). Subsequently, RNase BN was shown to also be able to process the CCA-encoded host E. coli tRNA precursors in vivo (8, 9). However, of the five E. coli RNases able to carry out the 3′-processing reaction, RNase BN was the least efficient (12, 13). Thus, under normal growth conditions, RNase BN is unlikely to function in total tRNA maturation, although it cannot be ruled out that the enzyme may participate in 3′-maturation of some select tRNA species (8). However, because E. coli mutants lacking RNase BN grow essentially normally (14–17), either such tRNAs must be nonessential, or their 3′-maturation can also be carried out by other RNases.

RNase BN was initially thought to be an exoribonuclease based on its ability to remove a mononucleotide residue from the 3′ terminus of synthetic tRNA precursors (11). This conclusion was strengthened by the subsequent finding that the enzyme is also a zinc phosphodiesterase (10). However, study of RNase Z enzymes from various other organisms showed that these enzymes are endoribonucleases (6, 18, 19), and the E. coli enzyme was also found to display endoribonuclease activity on certain tRNA precursors in vitro (14, 20). To help clarify this situation, we recently carried out a detailed analysis of RNase BN/RNase Z action on a variety of oligoribonucleotide substrates and showed that the enzyme can act both as a distributive exoribonuclease and an endoribonuclease depending on the nature of the substrate and on its 3′-terminal structure (21). For example, the presence of a CCA sequence or a 3′-phosphoryl group was found to inhibit RNase BN (11, 21). On the other hand, in a recent study (20), it was suggested that RNase BN can act on E. coli tRNA precursors and that it can actually remove the CCA sequence. Hence, the mode of action of RNase BN on tRNA precursors, the effect of the CCA sequence on the activity of the enzyme, and what determines the catalytic specificity have been unclear.

In this study, we analyzed the action of RNase BN on a variety of E. coli and phage T4 tRNA precursors. We show that RNase BN can act on tRNA precursors containing or lacking a CCA sequence and that it can do so as either an exoribonuclease or an endoribonuclease. However, its mode of cleavage is very dependent on the assay conditions, particularly with regard to the identity of the metal ion present. When conditions more closely resemble those thought to occur in vivo, RNase BN functions primarily as an endoribonuclease, although these are not necessarily the conditions under which RNase BN is most active. Thus, RNase BN specificity and efficiency can be greatly affected by assay conditions. Moreover, certain tRNA precursors are extremely poor substrates for RNase BN under any condition tested, which may explain why RNase BN is so poor at total tRNA maturation in vivo. These findings provide important information on the catalytic capabilities of RNase BN on tRNA precursors and help explain the known physiological properties of this enzyme.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

T4 polynucleotide kinase, DNase I, and RNase A were purchased from New England Biolabs. Calf intestine alkaline phosphatase and proteinase K were obtained from Fermentas. T4 RNA ligase, NucAwayTM spin columns, and the MEGAshortscriptTM kit were purchased from Ambion, Inc. The genomic DNA isolation kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). ExpressHyb hybridization solution was purchased from Clontech. [α-32P]ATP, [γ-32P]ATP, [5′-32P]pCp,2 and GeneScreen Plus hybridization transfer membrane were obtained from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. The GenEluteTM PCR clean-up kit was purchased from Sigma. The KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase was obtained from Novagen. SequaGel for denaturing urea-polyacrylamide gels was from National Diagnostics. The HisTrap HP column was obtained from Amersham Biosciences. All other chemicals were reagent grade. RNase BN was overexpressed and purified as described previously (14, 21). The purity of the RNase BN preparation was determined by silver staining of an overloaded SDS-polyacrylamide gel (2.5 μg of the purified protein). Only a single band at ∼35 kDa was observed; no minor contaminating proteins were detected.

Isolation of DNA from Phage T4 and E. coli

50 μg of DNase I and 100 μg of RNase A were added to 750 μl of phage T4 preparation (1011 plaque-forming units/μl), and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. 150 μl of lysis buffer (0.4 m EDTA, pH 8.0, 1% SDS, and 50 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.0) and 10 μl of proteinase K (10 μg/μl) were then added, and incubation was continued at 65 °C for 30 min. The mixture was then vortexed for 10 min with 750 μl of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:24:1) and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min. The aqueous layer was re-extracted with 750 μl of chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1), and the DNA in the aqueous layer was precipitated at −20 °C for 2 h in the presence of 0.1 volume of 0.3 m sodium acetate, pH 5.0, and 0.7 volume of isopropyl alcohol. DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 20,000 × g, and the DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried, and dissolved in 50 μl of DNase-free water.

E. coli DNA was purified using the genomic DNA isolation kit (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer's protocol. B. subtilis DNA was obtained from Dr. Chaitanya Jain (University of Miami).

Synthesis of tRNA Precursors

Genomic DNAs, obtained as described above, were used as the templates in PCRs using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase to prepare mature or pre-tRNA genes. In all cases, the forward primer contained a T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence. PCR products were purified using the GenEluteTM PCR clean-up kit and were used as the templates in in vitro transcription reactions for the synthesis of tRNAs using the MEGAshortscriptTM transcription kit. Transcription conditions were according to the manufacturer's protocol. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was extracted twice with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), and the tRNA products were precipitated at −20 °C in the presence of 0.1 volume of 20% potassium acetate and 2.5 volumes of 95% ethanol for 1 h. The samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, followed by washing with 70% ethanol. The supernatant fraction was discarded, and the RNA pellet was air-dried and dissolved in 50 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water.

Northern Blot Analysis

tRNA samples digested with RNase BN were resolved on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris borate/EDTA buffer and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by horizontal transfer for 1.5 h at 150 mA using 0.5× Tris borate/EDTA as the transfer solution. DNA oligonucleotide probes complementary to the 5′-end of the tRNA were 32P-labeled at their 5′-ends with T4 polynucleotide kinase. Probes were allowed to anneal to the transferred RNA by overnight incubation in ExpressHyb hybridization solution, and the detected bands were visualized by PhosphorImager analysis (GE Healthcare).

3′-End Labeling of tRNA

tRNAs were labeled at their 3′-ends with [5′-32P]pCp using T4 RNA ligase in the presence of unlabeled ATP at 4 °C for 16 h. 20 μl of the labeling reaction mixture contained 10 pmol of tRNA, 12 pmol of [5′-32P]pCp, 10 units of T4 RNA ligase, and 1× T4 RNA ligase buffer (0.05 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 0.01 m MgCl2, 0.01 m dithiothreitol, and 1 mm unlabeled ATP). Unincorporated [32P]pCp was removed using a NucAwayTM spin column. The 3′-terminal phosphate was removed by treatment with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase. The 20-μl dephosphorylation reaction contained 5 pmol of [3′-32P]pCp-labeled tRNA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1× calf intestine alkaline phosphatase buffer, and 1 unit of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and then extracted twice with the same volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). tRNAs were precipitated at −20 °C for 1 h in the presence of 0.1 volume of 20% potassium acetate and 2.5 volumes of 95% ethanol. The tRNA pellet was collected by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min, air-dried, and dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water.

3′-tRNA Processing Assay

Each 30-μl reaction mixture containing either 20 mm HEPES, pH 6.5, 200 mm potassium acetate, and 0.2 mm CoCl2 or 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 200 mm potassium acetate, ∼0.05 μm tRNA substrates, and 0.14 μm purified RNase BN was incubated at 37 °C. Portions were taken at the indicated times, and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 2 volumes of gel loading buffer (95% formamide, 20 mm EDTA, 0.05% SDS, 0.025% bromphenol blue, and 0.025% xylene cyanol). Reaction products were resolved on 20% denaturing 7.5 m urea-polyacrylamide gels and visualized using a STORM 840 phosphorimaging device (GE Healthcare). Quantification was carried out using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare).

AMP Incorporation Assay

Assays were carried out in 20-μl reaction mixtures containing 20 mm HEPES, pH 6.5, 200 mm potassium acetate, 0.2 mm CoCl2, 0.11 μm T4 tRNAPro-Ser substrate, 0.14 μm purified RNase BN, 1.0 μg of purified tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, 1 mm unlabeled CTP, and 22 pmol of [α-32P]ATP. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 37 °C, and two samples were withdrawn at the indicated times. 150 μl of 0.5% (w/v) yeast RNA and 200 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid were added to one set of samples to stop the reaction. The samples were placed in ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Pellets were collected and dissolved in 50 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, and the radioactivity associated with the pellets was determined by liquid scintillation counting using an LS 6500 multipurpose scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

RNA loading dye (2 volumes) was added to the other set of samples to stop the reaction. The products were resolved on a denaturing 7.5 m urea-polyacrylamide gel and visualized using the STORM 840 phosphorimaging device.

RESULTS

The action of E. coli RNase BN/RNase Z on tRNA precursors has remained unclear. In the earliest studies, RNase BN was shown to be required for maturation of certain phage T4 tRNA precursors that lack an encoded CCA sequence (11, 22), and such an activity is consistent with that of other RNase Z enzymes, which generally cleave after the discriminator residue (6, 18). Interestingly, RNase BN also could act on the E. coli tRNA precursor analog tRNA-CCA-Cn in vitro (23) and on E. coli tRNA precursors in vivo to generate mature tRNAs (9, 12), indicating that it could process CCA-containing precursors and that the CCA sequence was retained. These data also are consistent with our recent studies that showed that RNase BN can remove residues following a CCA sequence but that it slows dramatically at a CCA sequence in model RNA substrates (21). Hence, the recent report of Takaku and Nashimoto (20) that RNase BN cleaves mature and precursor E. coli tRNAs to remove the CCA sequence was quite surprising. As a consequence, we have re-examined the action of RNase BN on representative E. coli tRNA precursors that contain a CCA sequence and also on a phage T4 precursor and a B. subtilis precursor that lack the CCA sequence to ascertain the products of RNase BN action and to determine whether RNase BN functions as an exoribonuclease or endoribonuclease on these substrates.

Action of RNase BN on a CCA-less tRNA Precursor

RNase Z enzymes from most organisms cleave tRNA precursors lacking a CCA sequence in an endonucleolytic fashion right after the discriminator nucleotide to generate a substrate for subsequent CCA addition by tRNA nucleotidyltransferase (1–3, 5, 24). To determine the mode of action of RNase BN on a tRNA precursor of this type, we prepared by in vitro transcription the phage T4 dimeric tRNAPro-Ser precursor (Fig. 1A), known to be a substrate for 3′-processing by RNase BN in vivo (23, 25, 26). This RNA was treated with purified RNase BN, and the products were analyzed in detail.

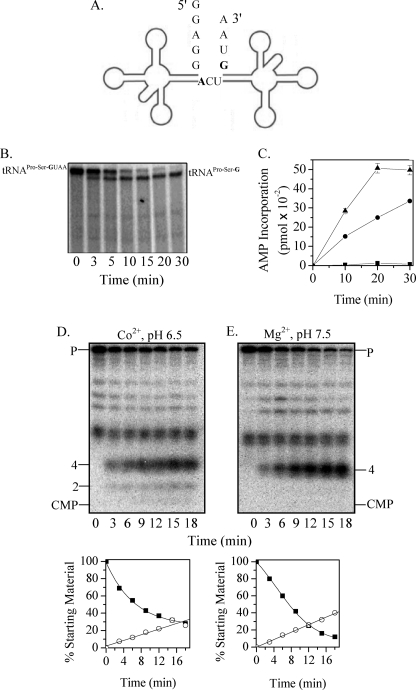

FIGURE 1.

Processing of phage tRNAPro-Ser precursor by RNase BN. A, shown is the structure of phage T4 tRNAPro-Ser dimeric precursor. The discriminator nucleotides are shown in boldface. B, uniformly 32P-labeled phage T4 tRNAPro-Ser (25 nm) was used as the substrate. Digestion was carried out in the presence of Co2+ at pH 6.5 with 0.14 μm RNase BN for the indicated times. Products were analyzed by 6% denaturing PAGE. C, [32P]AMP incorporation was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures” using unlabeled phage T4 tRNAPro-Ser precursor (0.11 μm) as the substrate. Portions were withdrawn at the indicated time points. High molecular weight products were precipitated by 10% trichloroacetic acid, and radioactivity associated with the precipitate was counted in a scintillation counter. ■, tRNAPro-SerGUAA, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase; ●, tRNAPro-SerG, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, RNase BN; ▴, tRNAPro-SerGUAA, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, RNase BN. D and E, phage T4 tRNAPro-Ser dimeric precursor (12 nm), labeled at its 3′-end with [32P]pC as described under “Experimental Procedures,” was used as the substrate. Digestion with RNase BN (0.04 μm) was carried out in the presence of either Co2+ at pH 6.5 (D) or Mg2+ at pH 7.5 (E). Quantitation of the data in D and E is shown below the gels. Disappearance of the tRNA precursor (P) (■) and appearance of the 4-nt product (○) are presented as the percentage of the initial amount of precursor. All bands shorter than the full-length tRNAPro-Ser precursor are incomplete transcripts that are labeled with [32P]pCp.

As shown in Fig. 1B, treatment with RNase BN led to the disappearance of the 32P-labeled dimeric precursor with the concomitant increase in a slightly shorter product that migrated in the position of the dimer from which the 3′-terminal UAA residues have been removed. To confirm that RNase BN removes the 3 precursor-specific residues from the 3′-end of tRNASer, the RNase BN cleavage reaction was repeated with nonradioactive precursor in the presence of tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, CTP, and [α-32P]ATP. If the complete UAA sequence were removed by RNase BN, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase would add CC-32P-A following the discriminator nucleotide. That this occurs is shown in Fig. 1C. No [32P]AMP was incorporated into the dimeric precursor in the absence of RNase BN, but there was considerable incorporation (0.46 pmol) when RNase BN was present. This level of incorporation amounted to ∼85% of the tRNA precursor added. As a control, [32P]AMP incorporation into tRNAPro-Ser lacking the UAA residues was also measured. In this case, incorporation continued for 30 min and did not yet reach a limit. The higher level in the presence of RNase BN appears to be due to some cleavage of the dimeric precursor by RNase BN to individual tRNAPro and tRNASer, resulting in additional 3′ termini for CCA addition. This was confirmed by gel electrophoresis, which showed monomer-sized tRNA products (data not shown).

Of most interest to understanding the mode of action of RNase BN is the question of whether the UAA residues at the 3′ terminus of the dimeric precursor are removed by a single endonucleolytic cleavage or by exoribonucleolytic trimming because RNase BN has the capacity for either activity (21). To answer this question, [32P]pCp was added to the 3′ terminus, followed by removal of the 3′-phosphoryl group by phosphatase. The resulting labeled precursor was treated with RNase BN, and the cleavage products were analyzed on a 20% denaturing acrylamide gel. Fig. 1D shows that the major product produced was a tetranucleotide, with essentially no [32P]CMP evident. These data demonstrate that RNase BN removes the 3 extra nucleotides in pre-tRNAPro-Ser by endonucleolytic cleavage rather than by exonucleolytic trimming.

Action of RNase BN on a tRNA Precursor with a Long 3′-Trailer

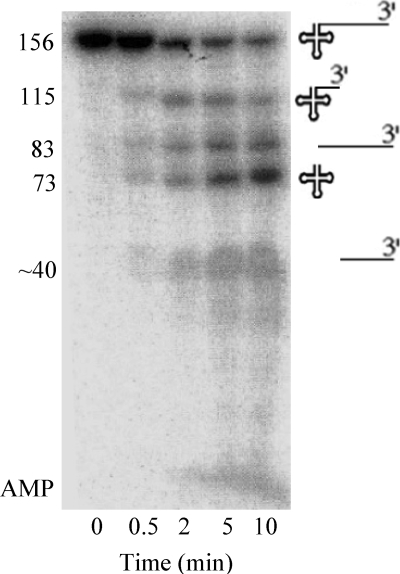

It was recently suggested that E. coli RNase Z cannot cleave pre-tRNAs with 3′-trailer sequences >6 nt (20). This observation is surprising considering that RNase BN/RNase Z can function to mature all E. coli tRNA precursors in a strain lacking other tRNA-processing exoribonucleases (8, 12). To re-examine this point in more detail, we prepared 32P-labeled B. subtilis pre-tRNAThr. This RNA contains tRNAThr plus an 83-nt 3′-trailer and is known to be cleaved by the B. subtilis RNase Z after the discriminator nucleotide (18). The precursor was treated with purified RNase BN, and the data from this experiment are presented in Fig. 2. RNase BN efficiently cleaved the 156-nt precursor to generate, as the major products, the 73-nt CCA-less tRNAThr and a second, slightly longer product corresponding to the 83-nt 3′-trailer. Interestingly, RNase BN also cleaved the precursor at a second position within the 3′-trailer to generate a product ∼115 nt in length and a smaller fragment from the 3′-trailer. This ∼115-nt product slowly disappeared with time, presumably due to an additional RNase BN cleavage after the discriminator residue that also generated tRNAThr. Nevertheless, these data clearly show that RNase BN can endonucleolytically cleave even long 3′-trailer sequences from tRNA precursors. A small amount of [32P]AMP also accumulated with increasing time of reaction due to the exoribonuclease activity of RNase BN (11, 21), most likely resulting from subsequent action on some of the product fragments generated by the initial endonucleolytic cleavages.

FIGURE 2.

Processing of B. subtilis tRNAThr precursor. Uniformly 32P-labeled tRNAThr precursor (0.26 μm) containing 83 extra nt at its 3′-end was treated with RNase BN (0.14 μm) in the presence of Co2+ at pH 6.5. The resulting products, displayed on the right, were analyzed by 8% denaturing PAGE.

Action of RNase BN on CCA-containing tRNA Precursors

To determine the mode of action of RNase BN on CCA-containing tRNA precursors and to examine the conclusion of Takaku and Nashimoto (20) that RNase BN removes the CCA sequence, we prepared several E. coli precursors by in vitro transcription and treated them with purified enzyme. We chose initially pre-tRNAPheV (Fig. 3A), a substrate studied in detail by Takaku and Nashimoto (20). Two variants were prepared containing either 3 or 6 nt following the CCA sequence. As shown in the Northern analyses in Fig. 3 (B and C), RNase BN converted each precursor to the size of mature tRNAPhe. No products shorter than the mature form were detectable. Moreover, RNase BN did not remove any residues from mature tRNAPhe (Fig. 3D). Thus, contrary to the results of Takaku and Nashimoto (20), under the assay conditions used, we found no evidence for removal of the CCA sequence by RNase BN.

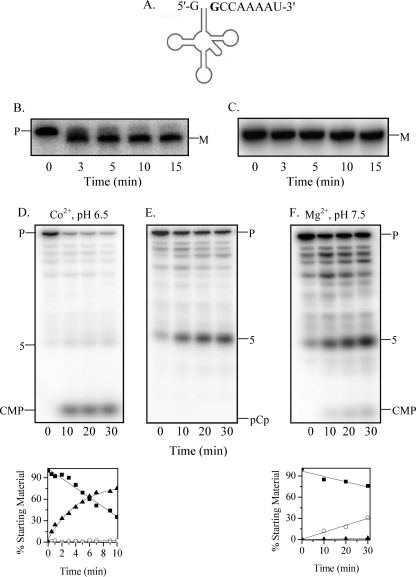

FIGURE 3.

Maturation of tRNAPheV precursor by RNase BN. A, shown is the structure of the E. coli tRNAPhe precursor. The discriminator nucleotide is shown in boldface. B, the tRNAPhe precursor (0.05 μm) with 6 extra 3′-residues after the CCA sequence was treated with RNase BN (0.14 μm), and the cleavage products were analyzed by 6% denaturing PAGE, followed by Northern blotting with a 5′-probe. C, the conditions were the same as described for B except that the precursor has 3 extra 3′-nt. D, the conditions were the same as described for B except that the substrate was mature (M) tRNAPhe. E and F, tRNAPhe labeled with [32P]pC at its 3′-end (48 nm) was treated with RNase BN (0.14 μm) in the presence of either Co2+ at pH 6.5 (E) or Mg2+ at pH 7.5 (F). The cleavage products were analyzed by 20% denaturing PAGE. Quantitation of the data from experiments similar to those in E and F is shown below the gels. Disappearance of the precursor (P) (■) and generation of CMP (▴) and 7-nt oligomer (○) products are presented as a percentage of the initial amount of precursor.

To ascertain the mode of removal of the extra 3′-residues on pre-tRNAPhe, [32P]CMP was added to the 3′ terminus of each precursor using RNA ligase, [32P]pCp, and phosphatase, and the products generated by RNase BN action were analyzed by PAGE (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, with the pre-tRNA containing 6 extra 3′-residues, both [32P]CMP and a 32P-labeled 7-mer oligonucleotide were released as the major products at a ratio of ∼3:1, respectively (Fig. 3E). A small amount of dinucleotide was also noted, suggesting that cleavage may also occur within the 3′-trailer. From these data, we concluded that RNase BN can remove extra residues following the CCA sequence by either an exonucleolytic or endonucleolytic mechanism. Both exonucleolytic and endonucleolytic products were also obtained when the shorter pre-tRNAPhe was the substrate, and CMP was again the major product (data not shown). Thus, under the assay conditions used (Co2+, pH 6.5), the exonucleolytic mode of processing predominates. However, as shown below, the mode of processing can be altered dramatically by a change in assay conditions.

The second E. coli tRNA precursor examined was that of tRNASelC. In previous work from our laboratory (12), it was shown that this tRNA was matured even in the absence of the major tRNA-processing exoribonucleases, suggesting that another enzyme, such as RNase BN, might be involved. Pre-tRNASelC with 4 nt following the CCA sequence (Fig. 4A) was synthesized and treated with purified RNase BN. The data in Fig. 4B show, by Northern analysis, that RNase BN readily converted the precursor to the size of the mature tRNA. Identical results were obtained with [α-32P]-labeled precursor (data not shown), confirming the Northern data. Furthermore, there was no reduction in size upon treatment of mature tRNASelC with RNase BN (Fig. 4C). Thus, for tRNASelC as well, there is no evidence for removal of the CCA sequence.

FIGURE 4.

Maturation of tRNASelC precursor by RNase BN. A, shown is the structure of the E. coli tRNASelC precursor. The discriminator nucleotide is shown in boldface. B, the tRNASelC precursor (0.04 μm) with 4 extra residues after the CCA sequence was treated with RNase BN (0.14 μm), and the cleavage products were analyzed by 6% denaturing PAGE, followed by Northern blotting with a 5′-probe. C, the conditions were the same as described for B except that the substrate was mature (M) tRNASelC. D, tRNASelC (0.04 μm) labeled with [32P]pC at its 3′-end was treated with RNase BN (0.3 μg) in the presence of Co2+ at pH 6.5. Cleavage products were analyzed by 20% denaturing PAGE. E, the conditions were the same as described for D except that the tRNA was labeled with [3′-32P]pCp. F, the conditions were the same as described for D except that reaction was carried out with Mg2+ at pH 7.5. Quantitation of the data from experiments similar to those in D and F is shown below the relevant gels. Disappearance of the tRNA precursor (P) (■) and generation of CMP (▴) are 5-nt oligomer (○) products are presented as a percentage of the initial amount of tRNA precursor.

Analysis of the mode of 3′-maturation using precursor labeled at its 3′ terminus with [32P]CMP revealed that RNase BN action was almost exclusively exonucleolytic, releasing only CMP (Fig. 4D). However, when the 3′-phosphoryl group from pCp addition was not removed, only the endonucleolytic product, a 5-nt long oligomer, was detectable (Fig. 4E), in keeping with the known inhibition of the exoribonuclease activity by a 3′-phosphoryl group (21). As with tRNAPhe, assay conditions dramatically affected the mode of 3′-processing of pre-tRNASelC (see below).

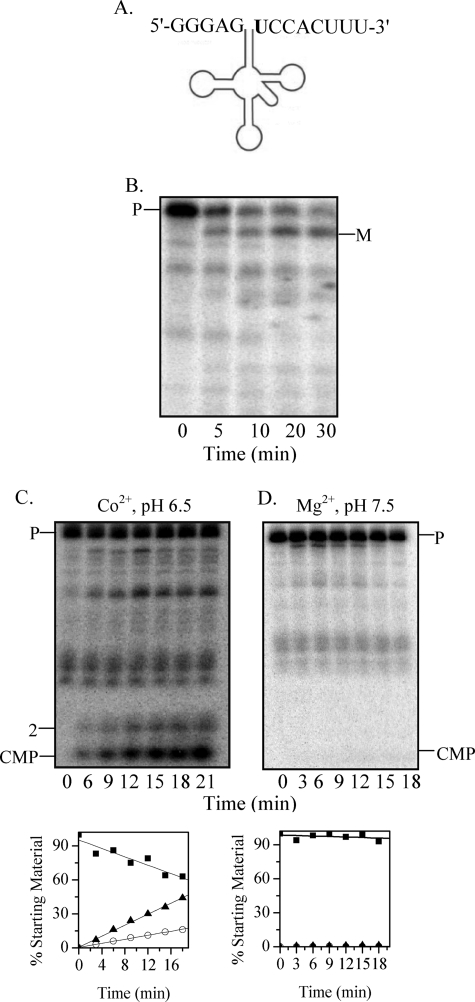

A third E. coli pre-tRNA, that of tRNACysT, which contained 4 nt following the CCA sequence (Fig. 5A), was also analyzed. Treatment of this precursor also generated a product that migrated with mature tRNACys (Fig. 5B), again providing no evidence for CCA removal. Determination of the mode of removal of the extra nucleotides using [3′-32P]CMP-labeled substrate, as described above, showed that CMP was the major product, indicating exoribonuclease action (Fig. 5C). However, in this case, a significant amount of dinucleotide was also generated by the endoribonuclease activity (Fig. 5C). Some anomalous internal cleavage was also observed (Fig. 5C). Assay conditions also affected processing of this tRNA precursor, as shown below.

FIGURE 5.

Maturation of tRNACysT precursor by RNase BN. A, shown is the structure of the E. coli tRNACys precursor. The discriminator nucleotide is shown in boldface. B, uniformly 32P-labeled pre-tRNACys (0.05 μm) was used as the substrate. Digestion was carried out in the presence of Co2+ at pH 6.5 with 0.14 μm RNase BN for the indicated times. Products were analyzed by 6% denaturing PAGE. M, mature tRNACys. C and D, tRNACys (0.05 μm) labeled with [32P]pC at its 3′-end was treated with RNase BN (0.14 μm) in the presence of Co2+ at pH 6.5 (C) or Mg2+ at pH 7.5 (D). The cleavage products were analyzed by 20% denaturing PAGE. Quantitation of the data in C and D is presented below the gels. Disappearance of the tRNA precursor (P) (■) and generation of CMP (▴) and endonucleolytic (○) products are presented as a percentage of the initial amount of precursor.

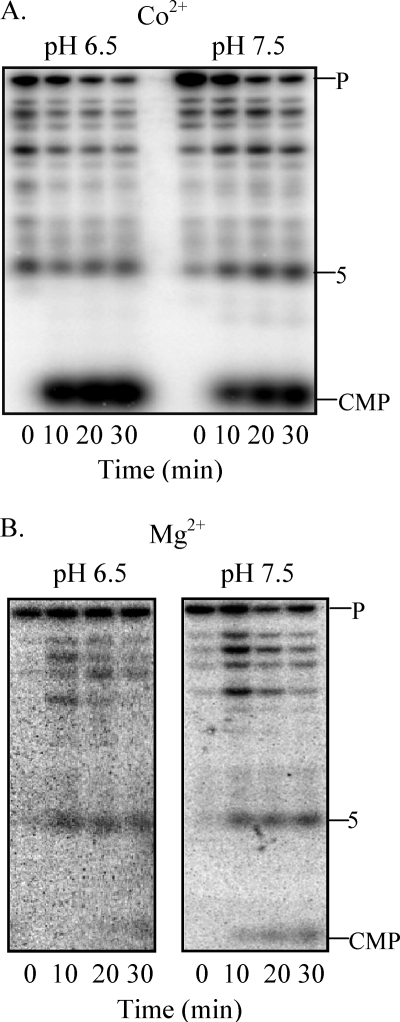

Effect of Assay Conditions on Mode of RNase BN Action

Previous work showed that the optimal in vitro assay conditions for RNase BN were at pH 6.5 in the presence of Co2+ (11, 21), and those were the conditions initially used in this study. However, because such conditions are unlikely to be present in vivo, we re-examined the mode of RNase BN action on the various pre-tRNAs using pH 7.5 in the presence of Mg2+. For the CCA-less precursors, tRNAPro-Ser (Fig. 1, D and E) and tRNAThr (data not shown), there was essentially no difference in the products generated or in their amounts. However, there were dramatic alterations in the products generated when the CCA-containing precursors were tested under the two assay conditions. Thus, for tRNAPhe (Fig. 3, E and F) and tRNASelC (Fig. 4, D and F), changing the conditions essentially eliminated the exoribonuclease activity. Based on the quantitation, the endoribonuclease activity on tRNAPhe remained at the same level, whereas with tRNASelC, it increased appreciably; but for both substrates, total processing activity decreased markedly due to the loss of exoribonuclease action. In contrast, with tRNACys as the substrate, changing the assay conditions completely eliminated both the exoribonuclease and endoribonuclease activities, and the precursor remained unprocessed (Fig. 5D). These data demonstrate that assay conditions can have a profound effect on RNase BN activity and on its mechanism of action, and this effect can vary substantially depending on the RNA substrate and whether or not a CCA sequence is present.

To define more carefully which aspect of the assay conditions is responsible for the mode of action of the enzyme, pH or metal ion, pre-tRNASelC was treated with RNase BN using multiple assay conditions. As shown in Fig. 6A, in the presence of Co2+, the predominant product at both pH 6.5 and 7.5 was CMP. In contrast, in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 6B), the predominant product was the 5-nt oligomer at both pH values. These data clearly indicate that the metal ion is the determining factor in whether RNase BN functions as an exoribonuclease or endoribonuclease.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of assay conditions on RNase BN specificity. [3′-32P]pC-labeled pre-tRNASelC (0.04 μm) was treated with RNase BN (0.14 μg) in the presence of Co2+ at pH 6.5 or pH 7.5 (A) or in the presence of Mg2+ at pH 6.5 or pH 7.5 (B). Cleavage products were analyzed by 20% denaturing PAGE.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study provide important information on E. coli RNase BN/RNase Z catalysis and function. We have shown that (a) RNase BN can process the 3′ termini of both CCA-less and CCA-containing pre-tRNAs; (b) contrary to the suggestion of Takaku and Nashimoto (20), RNase BN does not normally remove the CCA sequence from precursor or mature tRNAs; (c) RNase BN can act as either an exoribonuclease or endoribonuclease on tRNA precursors; and (d) the mode of action of RNase BN is dependent on the metal ion present. This combination of catalytic properties sets RNase BN apart from other RNase Z enzymes and raises again the question of what its function might be in E. coli. Despite its ability to act on tRNA precursors, there is no evidence that it does so in vivo except when all the other 3′-processing enzymes are absent or during bacteriophage T4 infection when it is required for T4 tRNA maturation (22). In fact, cells lacking RNase BN display no discernible phenotype (16).

The ability of RNase BN to process both CCA-less and CCA-containing tRNAs combines in this enzyme the catalytic properties of most RNase Z enzymes, which cleave after the discriminator nucleotide (11, 14), with those of the RNase Z from Thermotoga maritima, which cleaves right after the CCA sequence (6). This raises the question of why our results differ from those of Takaku and Nashimoto (20). Those workers suggested that E. coli RNase Z cleaved both mature tRNAs and tRNA precursors to remove the 3′-terminal CCA sequence. Aside from the fact that such a reaction would appear to be wasteful, requiring continued re-addition of the CCA sequence, we showed previously with model RNA substrates that RNase BN action is inhibited by the CCA sequence except for minor trimming of the terminal AMP residue (21). It is also known that end turnover of tRNA in vivo is due to the action of RNase T, not RNase BN (27). One possibility that might explain the difference in results is that Takaku and Nashimoto carried out all their studies at 50 °C with a much higher ratio of enzyme to substrate (20). Perhaps, at that elevated temperature, tRNA structure would be at least partially disrupted, altering the specificity of RNase BN for its substrates. However, when we tested RNase BN activity on tRNAPhe and tRNACys under the conditions used in Ref. 20, we were still unable to observe removal of the CCA sequence.3 Thus, further work will be necessary to reconcile the differences in data between the two laboratories.

In previous work using model RNA substrates, we showed that RNase BN had both exoribonuclease and endoribonuclease activities (21). The studies presented here extend those observations to tRNA precursors as well. With CCA-less substrates, the mode of cleavage was almost exclusively endonucleolytic, resulting in cleavage after the discriminator nucleotide; however, with CCA-containing tRNA precursors, either mode of action was possible and depended primarily on the metal ion present. In the presence of Co2+, RNase BN displayed increased activity and functioned largely as an exoribonuclease to remove extra 3′-residues from tRNA precursors. In the presence of Mg2+, its primary mode of action was as an endoribonuclease, cleaving after the CCA sequence. The role of the metal ion in the activity and specificity of RNase BN is of considerable interest for future structural and functional studies.

As noted, the action of RNase BN also varied dramatically with the pre-tRNA substrate. Thus, CCA-less tRNAs were cleaved endonucleolytically after the discriminator residue, whereas with CCA-containing molecules, residues following the CCA sequence could be removed either exonucleolytically or endonucleolytically. How the enzyme distinguishes the two types of substrates and what structural features of the tRNA determine this specificity remain to be explored. It should also be noted that several pre-tRNAs tested were poor substrates for RNase BN. These included tRNACys, which was active with Co2+ but was essentially inactive in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 5D). Pre-tRNALeuZ and pre-tRNAAlaU also were poorly acted upon by RNase BN even in the presence of Co2+.3 The inability of RNase BN to function efficiently on all pre-tRNAs likely explains why cells grow very slowly in the absence of all the other 3′-tRNA-processing enzymes present in E. coli (12).

The results presented here add considerably to our knowledge of RNase BN specificity and help explain what is known at present about its in vivo action on tRNA precursors. However, there is clearly still much to be learned about this interesting RNase with regard to its mechanism and its primary in vivo function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Georgeta Basturea and Pavanapuresan Vaidyanathan for helpful discussions and comments. We also thank Drs. Georgeta Basturea, Chaitanya Jain, and Arun Malhotra and Christie Taylor for reading and commenting on the manuscript. We thank Dr. Chaitanya Jain for providing B. subtilis DNA.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM16317.

T. Dutta and M. P. Deutscher, unpublished data.

- pCp

- cytidine 3′,5′-bis(phosphate)

- nt

- nucleotide(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Deutscher M. P. (1990) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 39, 209–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutscher M. P. (1995) in tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function (Soll D., Rajbhandary U. L. eds) pp. 51–65, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redko Y., Li de la Sierra-Gallay I., Condon C. (2007) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffer S., Rösch S., Marchfelder A. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2769–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel A., Schilling O., Späth B., Marchfelder A. (2005) Biol. Chem. 386, 1253–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minagawa A., Takaku H., Takagi M., Nashimoto M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15688–15697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubrovsky E. B., Dubrovskaya V. A., Levinger L., Schiffer S., Marchfelder A. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 255–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z., Deutscher M. P. (1996) Cell 86, 503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuven N. B., Deutscher M. P. (1993) FASEB J. 7, 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogel A., Schilling O., Niecke M., Bettmer J., Meyer-Klaucke W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29078–29085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asha P. K., Blouin R. T., Zaniewski R., Deutscher M. P. (1983) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 3301–3304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly K. O., Deutscher M. P. (1992) J. Bacteriol. 174, 6682–6684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutscher M. P., Li Z. (2001) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 66, 67–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezraty B., Dahlgren B., Deutscher M. P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16542–16545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z., Deutscher M. P. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 6064–6071 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schilling O., Rüggeberg S., Vogel A., Rittner N., Weichert S., Schmidt S., Doig S., Franz T., Benes V., Andrews S. C., Baum M., Meyer-Klaucke W. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320, 1365–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perwez T., Kushner S. R. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 60, 723–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pellegrini O., Nezzar J., Marchfelder A., Putzer H., Condon C. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 4534–4543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishii R., Minagawa A., Takaku H., Takagi M., Nashimoto M., Yokoyama S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14138–14144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takaku H., Nashimoto M. (2008) Genes Cells 13, 1087–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta T., Deutscher M. P. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15425–15431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidman J. G., Schmidt F. J., Foss K., McClain W. H. (1975) Cell 5, 389–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deutscher M. P. (1993) J. Bacteriol. 175, 4577–4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner A. M. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 883–885 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seidman J. G., McClain W. H. (1975) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72, 1491–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutscher M. P., Foulds J., McClain W. H. (1974) J. Biol. Chem. 249, 6696–6699 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutscher M. P., Marlor C. W., Zaniewski R. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 6427–6430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]