Abstract

Pulsatile insulin release from glucose-stimulated β-cells is driven by oscillations of the Ca2+ and cAMP concentrations in the subplasma membrane space ([Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm). To clarify mechanisms by which cAMP regulates insulin secretion, we performed parallel evanescent wave fluorescence imaging of [cAMP]pm, [Ca2+]pm, and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) in the plasma membrane. This lipid is formed by autocrine insulin receptor activation and was used to monitor insulin release kinetics from single MIN6 β-cells. Elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm induced, after a 2.7-min delay, coordinated oscillations of [Ca2+]pm, [cAMP]pm, and PIP3. Inhibitors of protein kinase A (PKA) markedly diminished the PIP3 response when applied before glucose stimulation, but did not affect already manifested PIP3 oscillations. The reduced PIP3 response could be attributed to accelerated depolarization causing early rise of [Ca2+]pm that preceded the elevation of [cAMP]pm. However, the amplitude of the PIP3 response after PKA inhibition was restored by a specific agonist to the cAMP-dependent guanine nucleotide exchange factor Epac. Suppression of cAMP formation with adenylyl cyclase inhibitors reduced already established PIP3 oscillations in glucose-stimulated cells, and this effect was almost completely counteracted by the Epac agonist. In cells treated with small interfering RNA targeting Epac2, the amplitudes of the glucose-induced PIP3 oscillations were reduced, and the Epac agonist was without effect. The data indicate that temporal coordination of the triggering [Ca2+]pm and amplifying [cAMP]pm signals is important for glucose-induced pulsatile insulin release. Although both PKA and Epac2 partake in initiating insulin secretion, the cAMP dependence of established pulsatility is mediated by Epac2.

Keywords: Calcium, Cyclic AMP, Diabetes, Glucose, Protein Kinase A, Signal Transduction, Epac, Evanescent Wave Microscopy

Introduction

Pancreatic β-cells release insulin in response to glucose stimulation, and appropriate secretion is essential for glucose homeostasis. Signals derived from glucose metabolism lead to closure of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels2 and depolarization of the plasma membrane. This in turn activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry, and the resulting elevation of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) triggers exocytosis of insulin granules (1). Studies of the detailed kinetics of glucose-stimulated insulin release have clarified that it consists of distinct regular pulses, the first of which is more pronounced (2, 3). It has been proposed that the initial and late secretion may reflect release of insulin from functionally distinct granule pools (4, 5). The first phase has been proposed to correspond to exocytosis of granules from a small readily releasable pool with rise of [Ca2+]i as the only triggering signal, whereas later secretion supposedly involves recruitment of granules from a reserve pool by a series of ATP- and Ca2+-dependent priming reactions (6). Glucose induces oscillations of [Ca2+]i in β-cells (7), and these oscillations seem to underlie pulsatile release of insulin from isolated islets (8, 9) and individual β-cells (10–12).

Ca2+-triggered exocytosis is potently amplified by cAMP (13), and this messenger has long been known to mediate the insulinotropic action of glucagon and the incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide 1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (13–15). In contrast, the role of cAMP in glucose-induced insulin secretion has been uncertain. Early studies indicated that glucose alone only modestly elevates cAMP (16–18) but that the sugar could amplify hormone-stimulated formation of cAMP (13, 19). More recently, fluorometric recordings of cAMP in MIN6 cells indicated that glucose alone elevates the intracellular cAMP level (20). Using a new technique for single-cell measurements of cAMP, we recently found that glucose triggers pronounced oscillations of the cAMP concentration beneath the plasma membrane ([cAMP]pm) and that these changes are important for regulating the kinetics of insulin secretion (21). However, the precise mechanisms by which cAMP acts remain unclear.

Protein kinase A (PKA) and the cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor cAMP-GEFII, also known as “Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 2” (Epac2), are the major cAMP effectors expressed in β-cells (22–24). Studies of insulin granule exocytosis based on cell membrane capacitance measurements have indicated that cAMP amplification of insulin secretion involves both PKA-dependent and PKA-independent mechanisms (25–28). Although many proteins involved in the stimulus-secretion coupling and exocytosis of insulin granules have been identified as targets for PKA phosphorylation (25), inhibitors of this kinase have surprisingly small effects on glucose-induced insulin secretion (29, 30). Such modest effects may be expected if PKA only amplifies first phase secretion as indicated by recent imaging of exocytosis with fluorescent tracers (31). The PKA-independent amplification of insulin secretion by cAMP is probably mediated by Epac2, which has been proposed to act via the small GTPase Rap-1 (24), the regulatory SUR1 subunit of the KATP channel (27) as well as via SNAP-25 (32), Rim2, and Piccolo (33), which are proteins involved in the exocytosis machinery.

The aim of the present study was to clarify mechanisms by which cAMP oscillations contribute to glucose-induced pulsatile insulin secretion in individual β-cells. The data indicate that cAMP amplifies both the first and the subsequent pulses of secretion via Epac2. PKA seems important for establishing pulsatile insulin release by promoting concomitant initial elevation of the subplasma membrane Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]pm) and [cAMP]pm, but the kinase is not required for maintaining already manifested pulsatile insulin secretion from glucose-stimulated β-cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Reagents of analytical grade and deionized water were used. Insulin, tolbutamide, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), EGTA, forskolin, methoxyverapamil, 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine (DDA), SQ22536, H89, and KT5720 were from Sigma. The Epac agonist 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (007) and its acetoxymethyl ester, and PKA antagonist 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer, were from Biolog Life Science Institute (Bremen, Germany). The acetoxymethyl esters of the Ca2+ indicators Fluo-4, Fluo-5F, Fura Red, and Indo-1 as well as Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, Opti-MEM®, and LipofectamineTM 2000 were obtained from Invitrogen. The Ca2+ indicator Fura-2-AM was provided by AnaSpec, Inc. (San José, CA).

Cell Culture and Transfection

MIN6 cells (34) of passages 17–30 were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 4.5 g/liter glucose and supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. INS1(832/13) cells were used in one experimental series. These cells were kept in RPMI 1640 medium containing 11.1 mm glucose, 10% fetal calf serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm l-glutamine, and 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. The same transfection protocol was used for both cell lines: ∼2 × 105 cells were suspended in 100 μl OptiMEM® medium containing 0.5 μl LipofectamineTM 2000 (Invitrogen) with 0.2–0.5 μg of plasmid DNA and plated on a 25-mm polylysine-coated coverslip. After 4 h when the cells were firmly attached, the transfection was interrupted by addition of 3 ml of complete cell culture medium, and the cells were maintained in this medium for 12–24 h. Prior to experiments, the cells were incubated for 30–60 min at 37 °C in buffer containing 125 mm NaCl, 4.9 mm KCl, 1.28 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 3 mm glucose, and 25 mm HEPES with pH adjusted to 7.40 with NaOH.

Measurements of [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]pm

Where indicated, MIN6 cells were loaded with the Ca2+-indicator Indo-1, Fura-2, Fluo-4, Fluo-5F, or Fura Red by 45–60-min incubation at 37 °C in experimental buffer supplemented with a 2–10 μm concentration of their respective acetoxymethyl esters. After rinsing the cells in indicator-free medium, [Ca2+]i was monitored in Fura-2-loaded cells using a Nikon Diaphot microscope equipped with a wide field epifluorescence illuminator, a 40 × 1.3-NA objective, and an intensified CCD camera (Extended ISIS-M, Photonic Science, Robertsbridge, UK). [Ca2+]i values were calculated from the 340/380 nm fluorescence excitation ratio after subtraction of background as described by Grynkiewicz et al. (35). Imaging of [Ca2+]pm in cells loaded with Fura Red, Fluo-4, Fluo-5F, or Indo-1 was performed with an evanescent wave microscope setup described below.

Measurements of [cAMP]pm

[cAMP]pm was measured using a fluorescent translocation biosensor as described previously (36). The biosensor consists of a membrane-anchored and truncated form of the PKA regulatory RIIβ subunit labeled or not with CFP, and a YFP-labeled PKA catalytic Cα subunit (Cα-YFP). Upon elevation of [cAMP]pm, Cα-YFP dissociates from the regulatory subunit at the plasma membrane and diffuses into the cytoplasm. This translocation is detected with evanescent wave microscopy as loss of membrane fluorescence.

Measurements of Insulin Secretion from Individual Cells

We recently demonstrated that insulin secretion can be recorded from individual cells by monitoring the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-induced formation of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) in the plasma membrane that follows autocrine activation of insulin receptors (11). Full-length “General receptor for phosphoinositides isoform 1” (Grp1) fused to four consecutive GFP molecules (GFP4-Grp1) or the isolated PH domain from protein kinase B/Akt fused to the cyan fluorescent protein (PHAkt-CFP) was used as the translocation biosensor for the concentration of membrane PIP3 (11, 21). The PH domain of Grp1 has a well documented binding selectivity for PIP3 (37), and that of Akt preferentially binds PIP3 and phophatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate over other phosphoinositides (38).

Evanescent Wave Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence in the subplasma membrane compartment was recorded with an evanescent wave microscopy setup built around an E600FN upright microscope (Nikon, Kanagawa, Japan) contained in an acrylic glass box thermostatted at 37 °C by an air-stream incubator. A helium-cadmium laser (Kimmon, Tokyo, Japan) provided 442-nm light for excitation of CFP, and an argon laser (Creative Laser Production, Munich, Germany) was used for GFP, Fura Red, Fluo-5F, Fluo-4 (488 nm) and YFP (514 nm) excitation. A diode-pumped solid-state laser provided 355-nm light (Zouk, Cobolt AB, Stockholm, Sweden) for Indo-1 excitation. The laser beams were merged with dichroic mirrors (Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT), homogenized, and expanded by a rotating light shaping diffuser (Physical Optics Corp., Torrance, CA) before being refocused through a modified quartz dove prism (Axicon, Minsk, Belarus) with 70° angle to achieve total internal reflection. Laser lines were selected with interference filters (Semrock, Rochester, NY) in a motorized filter wheel equipped with a shutter (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) blocking the beam between image captures. The coverslips with attached cells were used as exchangeable bottoms of an open 200-μl superfusion chamber. The chamber was mounted on the custom-built stage of the microscope such that the coverslip was maintained in contact with the dove prism by a thin layer of immersion oil. Fluorescence from the cells was collected through a 40 × 0.8-NA water immersion objective (Nikon), selected with interference filters (Semrock) at 405/35 nm (center wavelength/half-bandwidth) and 483/32 nm for Indo-1; 485/25 nm for CFP; 530/50 nm for GFP, Fluo-5F, and Fluo-4; 542/27 nm for YFP; and a >645-nm glass filter for Fura Red, and detected with a back-illuminated EMCCD camera (DU-887; Andor Technology, Belfast, Northern Ireland) under MetaFluor (Molecular Devices, Downington, PA) software control. If not otherwise stated, images were acquired every 2–5 s using exposure times in the 100–200-ms range.

Electrophysiology

Membrane potential was recorded in the perforated patch whole cell configuration using an EPC-9 patch clamp amplifier and Pulse software (Heka Elektronik, Lamprecht/Pfalz, Germany). Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries, coated with dental wax, and fire-polished. The extracellular solution consisted of 138 mm NaCl, 5.6 mm KCl, 2.6 mm CaCl2, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 3 mm glucose, and 5 mm HEPES (pH 7.4 using NaOH). The pipette solution consisted of 76 mm K2SO4, 10 mm KCl, 10 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 5 mm HEPES (pH 7.15 with KOH) supplemented with 0.24 mg/ml amphotericin B. Drugs were dissolved in extracellular solution and applied locally through a 100-μm capillary.

siRNA Treatment, Real-time PCR, and Western Blotting

Where indicated, MIN6 cells were transfected with 100 nm siRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) against Epac2 (5′-gaguuagcagguguucucatt-3′) or luciferase-GL3 as control (5′-cuuacgcugaguacuucgatt-3′), alone or together with GFP4-Grp1, 24–72 h prior to experiments. Efficiency of knockdown was verified with real-time PCR and immunoblotting. Total mRNA were isolated from MIN6 cells using RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions and reverse-transcribed with SuperScriptTM III First-strand synthesis system for reverse-transcription-PCR (Invitrogen) using random primers. The real-time PCR was performed using SYBR® Green JumpStart Taq ReadyMixTM (Sigma-Aldrich) and the following primers: Epac2 sense, 5′-ggcgtaccagatgacaacct-3′ and antisense, 5′-cctcctcaggaacaaatcca-3′, β-actin sense, 5′-gttacaggaagtccctcacc-3′ and antisense 5′-ggagaccaaagccttcatac-3′. PCR products were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin, and expression levels are given relative to control according to the formula: fold change = 2ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt = [Ct(Epac2 siRNA) − Ct(β-actin)] − [Ct(Epac2 control) − Ct(β-actin control)].

The level of Epac2 protein was determined by Western blotting. Samples were prepared by washing the MIN6 cells twice with phosphate-buffered saline followed by lysis in a buffer containing 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mm EGTA, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min. After lysis, the preparations were collected and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 0.1% SDS, glycerol, and 2-mercaptoethanol, and boiled for 5 min. 20 μl of each sample was then subjected to SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblot analysis was performed with a mouse polyclonal antibody against Epac2 (generous gift from Johannes Bos, Utrecht University) using an ECL Plus Western blot detection system (GE Healthcare). Immunoreactive bands were imaged on a Kodak image station 4000MM.

Data and Statistical Analysis

Image analysis was performed using MetaFluor, MetaMorph (Universal Imaging), and ImageJ (W. S. Rasband, National Institutes of Health) software. Fluorescence intensities are expressed as changes in relation to initial fluorescence after subtraction of background (ΔF/F0). Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) and Illustrator (Adobe Systems, San José, CA) software were used for curve fitting and illustrations. All data are presented as mean values ± S.E. Differences were statistically evaluated by two-tailed Student's t test.

RESULTS

Glucose Induces Concomitant Elevations of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm, which Trigger Pulsatile Insulin Release

MIN6 β-cells responded after a 2–3-min delay to elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm with slow oscillations of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm reported with evanescent wave microscopy and the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 and a PKA-based translocation biosensor (36), respectively (Fig. 1A). Cells expressing the PIP3-binding translocation biosensor GFP4-Grp1 showed an analogous response. After an initial increase of the fluorescence (124 ± 13%, n = 36) there were pronounced oscillations from a slightly elevated level (frequency 0.21 ± 0.01 min−1, n = 36; Fig. 1A). We have previously demonstrated that this PIP3 response reflects autocrine activation of insulin receptors and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, which in turn parallels insulin secretion (11, 21).

FIGURE 1.

Glucose triggers oscillations of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm that underlie pulsatile insulin release. A, evanescent wave microscopy recordings of PIP3 with GFP4-Grp1 (black trace, reflecting insulin secretion kinetics), [cAMP]pm with ΔRII-CFP-CaaX and Cα-YFP (green trace), and [Ca2+]pm with Fluo-4 (red trace) in three separate MIN6 β-cells. Elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm triggers oscillations in all three messengers. Images of GFP4-Grp1 fluorescence are from the time points indicated by the numbered arrowheads. B, simultaneous evanescent wave microscopy recordings of PIP3 with PHAkt-CFP (black trace), [cAMP]pm with Cα-YFP and a nonfluorescent ΔRII-CaaX (green trace), and [Ca2+]pm with Indo-1 (red trace) during stimulation of MIN6 cells with 20 mm glucose, showing coordinated increases of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm that precedes the increase of PIP3. C, imposed elevations of cAMP by intermittent application of 50 μm IBMX trigger pulsatile insulin secretion (n = 13).

To clarify the temporal relationship between the messengers, we simultaneously recorded PIP3, [cAMP]pm, and [Ca2+]pm in the same cell using modified versions of the biosensors to avoid spectral overlap between the signals. Fig. 1B shows that elevation of the glucose concentration caused concomitant elevations of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm that were followed by a rise of PIP3. Although [Ca2+]pm increased before [cAMP]pm in some cells and after in others, the PIP3 response was typically delayed further. In simultaneous recordings of [cAMP]pm and PIP3, the glucose-induced increase in [cAMP]pm preceded that of PIP3 by 14 ± 3 s (n = 30). Most of this delay is explained by the time required for insulin receptor signal transduction, PIP3 formation, biosensor diffusion, and association with the membrane. Accordingly, exposure of the cells to 100 nm exogenous insulin caused membrane translocation of GFP4-Grp1 after 10 ± 1 s (n = 13; data not shown).

To test whether oscillations in [cAMP]pm are sufficient to drive pulsatile insulin secretion from glucose-stimulated β-cells, MIN6 cells exposed to 11 mm glucose were subjected to brief (2–5 min) applications of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX, which results in elevations of [cAMP]pm (36). Each application of IBMX triggered a rise of PIP3 that returned to base line when IBMX was removed (n = 13). This effect is particularly evident in Fig. 1C, which shows a cell with an initial peak response to glucose followed by stable, suprabasal second phase secretion. Imposed oscillations of [cAMP]pm can thus generate pulsatile insulin secretion from glucose-stimulated β-cells.

Proper Glucose Stimulation of Insulin Secretion Requires PKA Activity

Suppression of cAMP production by inhibition of adenylyl cyclases with 50 μm DDA markedly reduced the PIP3 response to glucose stimulation (Fig. 2, A, B, and E). In cells pretreated with DDA, the initial PIP3 response amplitude was reduced to 64 ± 8% of control (p < 0.01, n = 17). Although the amplitudes were decreased, glucose still triggered PIP3 oscillations in most cells exposed to DDA (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained with inhibitors of PKA. Accordingly, the amplitudes of the initial PIP3 response to glucose were reduced to 66 ± 7% (p < 0.01, n = 35) and 41 ± 10% (p < 0.001, n = 19) of control by 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS and 2 μm KT5720, respectively (Fig. 2, C–E), but the sugar still triggered PIP3 oscillations. However, washout of the adenylyl cyclase inhibitors or PKA inhibitors did not result in consistent normalization of the response amplitude within the time frame of the experiment. We also tested the importance of PKA for Ca2+ influx and insulin secretion elicited by depolarization with KCl, which preferentially triggers the fusion of primed readily releasable granules (39). When the cells were exposed to 30 mm KCl there was a rapid increase of [Ca2+]pm, followed after 16 ± 3 s (n = 14) by pronounced rise of GFP4-Grp1 fluorescence (92 ± 15% fluorescence increase, n = 14) and a decline to a sustained plateau (Fig. 2, F and G). The GFP4-Grp1 responses were not different in cells depolarized in the presence of Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS or DDA (Fig. 2, F–H), suggesting that cAMP/PKA is not required for the KCl-evoked exocytosis of primed granules. It was ascertained that the effects of the adenylyl cyclase and PKA inhibitors were not due to a direct effect on phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Accordingly, slight tendencies of DDA and Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS to reduce PIP3 formation induced by 300 nm insulin did not reach statistical significance (−11 ± 6%, n = 12 for DDA and −11 ± 8% for Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS; n = 8; data not shown). Similarly, when added to unstimulated cells, neither of the inhibitors affected the insulin-induced PIP3 response (Fig. 2I). Together, these results indicate that activation of PKA is important for the ability of glucose to initiate insulin secretion properly.

FIGURE 2.

PKA is involved in glucose initiation of insulin secretion. A, evanescent wave microscopy recording of pulsatile insulin release (PIP3 oscillations) from an individual GFP4-Grp1-expressing MIN6 β-cell stimulated by elevating the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm. B, suppression of the glucose-induced secretory response by 50 μm adenylyl cyclase inhibitor DDA (n = 17). C and D, effect of the PKA inhibitors Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (100 μm, n = 35) (C) and KT5720 (2 μm, n = 19) (D) on the glucose-induced insulin secretory responses. E, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the effects of DDA and PKA inhibitors on the amplitude of the initial GFP4-Grp1 response induced by 11 mm glucose. All values are expressed relative to control (11 mm glucose). F and G, simultaneous evanescent wave microscopy recordings of PIP3 with GFP4-Grp1 (black traces) and [Ca2+]pm with Fura Red (dotted gray traces) in MIN6 β-cells depolarized with 30 mm KCl in the presence of 3 mm glucose under control conditions and after exposure to 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS. Images were acquired every 2 s. The Fura Red traces have been inverted to show increases in [Ca2+]pm as upward deflections. H, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the amplitudes of the depolarization-induced GFP4-Grp1 translocation in the absence (n = 37) or presence of 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (n = 47) or 50 μm DDA (n = 20). I, 2 μm KT5720 (open symbols) and 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (gray symbols) were without effects on GFP4-Grp1 translocation induced by addition of 300 nm insulin (black symbols, control; n = 12–15 cells). *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 for difference from control.

Temporal Dissociation of the Glucose-induced Initial [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm Responses Results in Reduced Insulin Secretion

We next investigated whether inhibition of PKA interferes with the glucose-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i. MIN6 cells loaded with Fura-2 responded to elevations of the glucose concentration with slow, large amplitude [Ca2+]i oscillations (first peak, 306 ± 40 nm; frequency, 0.27 ± 0.01 min−1; n = 30; Fig. 3A). Inhibition of PKA with 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS was without detectable effect on the magnitude of the glucose-induced [Ca2+]i response (first peak, 340 ± 60 nm) and the frequency of the oscillations (0.32 ± 0.02 min−1; n = 15; Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained when Ca2+ was instead measured in the submembrane space with the much lower affinity indicator Fluo-5F (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

PKA inhibition changes the timing of glucose-stimulated Ca2+ influx and insulin secretion but is without effect on the elevation of cAMP. A and B, wide-field epifluorescence microscopy recordings of [Ca2+]i in single MIN6 β-cells loaded with Fura-2 and stimulated by elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm in the absence (A) (n = 19) or presence (B) (n = 27) of 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS. Representative single-cell traces are shown. C, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the glucose-induced [Ca2+]pm elevation detected with the low-affinity Ca2+ indicator Fluo-5F in the absence or presence of PKA inhibitors. D and E, simultaneous evanescent wave microscopy recordings of [Ca2+]pm with Fura Red (dotted gray traces) and PIP3 with CFP-PHAkt (black traces) during elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm in control MIN6 β-cells and those exposed to 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (added 5 min before the increase of glucose). The Fura Red traces have been inverted to show increases in [Ca2+]pm as upward deflections. F and G, simultaneous evanescent wave microscopy measurements of PIP3 with CFP-PHAkt (black traces) and [cAMP]pm with Cα-YFP and ΔRII-CaaX (dotted gray traces) after elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm in the absence (A) (n = 100) or presence (B) (n = 35) of 2 μm KT5720. The dashed lines have been included to visualize the delays between glucose stimulation and rise of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm in the absence and presence of PKA inhibitor. H, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the effect of 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS on the initial PIP3 and [Ca2+]pm responses to glucose. I, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the effect of 2 μm KT5720 on the initial PIP3 and [cAMP]pm response amplitudes to glucose. J, correlation between the amplitude of the PIP3 response and the temporal relationship of the [cAMP]pm and PIP3 increases in the absence of PKA inhibitor. Average time differences for cells in which cAMP precedes (n = 59) or lags behind (n = 17) PIP3 by >10 s are plotted against the PHAkt-CFP response amplitude. *, p < 0.05 for difference from control; ***, p < 0.001 for difference from cells with cAMP behind.

Simultaneous evanescent wave microscopy recordings of [Ca2+]pm with Fura Red and PIP3 with CFP-PHAkt demonstrated that [Ca2+]pm started to increase 164 ± 5 s after glucose stimulation and PIP3 after an additional 14 ± 3 s (n = 20; Fig. 3D). Inhibition of PKA with Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS reduced the delay between glucose stimulation and elevation of [Ca2+]pm to 134 ± 7 s (n = 11, p < 0.01) without significantly affecting the subsequent delay of the PIP3 elevation (19 ± 5 s; Fig. 3, D and E). Similar results were obtained with KT5720 (data not shown). Although the CFP-PHAkt fluorescence response to glucose was suppressed to 67% in the presence of PKA inhibitor (p < 0.05), there was no difference in the magnitude of the Fura Red response (Fig. 3H).

Also, the amplitude of the glucose-induced rise in [cAMP]pm was unaffected by PKA inhibition with 2 μm KT5720 (Fig. 3, F, G, and I). Moreover, the timing of the response was unchanged with a 176 ± 6 s (n = 100) delay between glucose stimulation and elevation of [cAMP]pm in control cells compared with 176 ± 10 s (n = 35) in KT5720-treated cells. However, simultaneous recordings of cAMP and PIP3 indicated a striking shift in the timing of cAMP and insulin release. In control cells stimulated with 11 mm glucose alone, the initial increase in [cAMP]pm preceded that of PIP3 in 78% of the cells, and the average time difference for all cells was 20 ± 4 s (n = 100; Fig. 3F). In contrast, during treatment with KT5720, the rise of [cAMP]pm typically lagged behind that of PIP3, with an average time difference of 17 ± 6 s (n = 35; Fig. 3G). The earlier PIP3 response reflects the shortened delay between glucose stimulation and elevation of [Ca2+]pm (see above), and under these conditions the amplifying cAMP signal has not yet been generated. Because the magnitudes of the [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm elevations were unaffected, it seems likely that the temporal dissociation of the two signals explains the suppression of the early secretory response after PKA inhibition. Indeed, glucose elicited a 75% greater increase of PHAkt-CFP fluorescence in control cells with [cAMP]pm increasing >10 s before PIP3 than in the less common control cells with [cAMP]pm increasing >10 s after PIP3 (n = 22; Fig. 3J).

To test the hypothesis further that dissociation of the triggering Ca2+ and amplifying cAMP signals underlies the impaired secretory response after PKA inhibition, the cells were stimulated by elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm, followed after 1 min by depolarization with the KATP channel blocker tolbutamide. This treatment triggered Ca2+ influx before the glucose-induced cAMP signal was manifested and was associated with a smaller PIP3 response (77 ± 5% of that obtained with 11 mm glucose alone; p < 0.001, n = 141 and 157 cells with and without tolbutamide, respectively; Fig. 4, A and C). If glucose-induced Ca2+ influx was instead prevented by exposure to the hyperpolarizing KATP channel opener diazoxide for a longer period than normally required for the cAMP rise, the presence of a PKA inhibitor did not affect the PIP3 response when [Ca2+]i was subsequently allowed to increase after washout of diazoxide (Fig. 4, B and C).

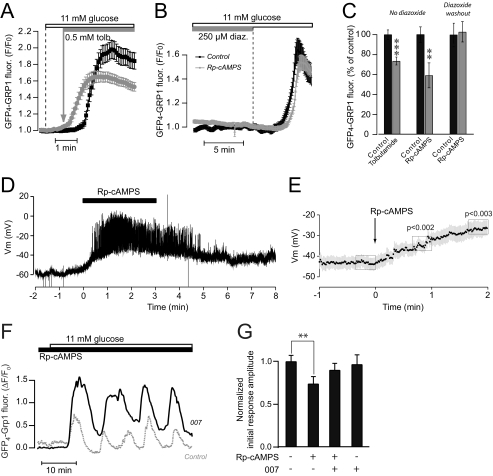

FIGURE 4.

Dissociation of the triggering Ca2+ and amplifying cAMP signals reduces glucose-induced insulin secretion. A, evanescent wave microscopy recordings from MIN6 cells expressing GFP4-Grp1. The cells were exposed to a rise of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm in some cells followed by the addition of 0.5 mm tolbutamide after 1 min. The traces are means ± S.E. of 25 cells in one control experiment (black trace) and 27 cells exposed to tolbutamide in one experiment (gray trace). B, evanescent wave microscopy recordings from MIN6 cells expressing GFP4-Grp1. The cells were hyperpolarized with 250 μm diazoxide, exposed to 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (gray) or vehicle (black) followed by elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm and subsequent washout of diazoxide. Data are presented as means ± S.E. for 35 control cells and 28 cells exposed to Rp-8CPT-cAMPS. C, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the initial response amplitudes to 11 mm glucose in the absence (black) or presence (gray) of 0.5 mm tolbutamide, 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS, or 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS following washout of diazoxide. n = 30–85 cells. D, membrane potential recording from a single MIN6 β-cell within a small cell cluster exposed to 3 mm glucose. Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (100 μm) was applied at t = 0 s as indicated. E, means ± S.E. from 14 recordings as shown in D. F, evanescent wave microscopy recording of PIP3 dynamics with GFP4-Grp1 during elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm in the presence of 100 μm Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS with (n = 40) or without (n = 31) preincubation for 10 min with the Epac-selective agonist 007. G, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the effects of Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS and 007 on the initial PIP3 response amplitude induced by 11 mm glucose. All values are normalized to the effect of 11 mm glucose alone, n = 31–53 cells. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 for difference from control.

Because PKA-mediated phosphorylation has been reported to increase the KATP channel activity (40, 41), we hypothesized that PKA inhibition may accelerate the glucose-induced depolarization by decreasing KATP channel activity. The membrane potential was therefore recorded in MIN6 cells using the patch clamp technique in the perforated patch configuration. In cells exposed to 3 mm glucose, PKA inhibition by Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS indeed caused depolarization, often associated with the appearance of action potentials (Fig. 4, D and E).

We next tested the possible role of Epac as mediator of cAMP-amplified insulin secretion. Whereas 100 μm Epac agonist 007 had little effect on the PIP3 response induced by rise of glucose from 3 to 11 mm under control conditions, it partially restored the response in cells treated with 100 μm PKA inhibitor Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (Fig. 4, F and G) without changing the timing of the PIP3 signal (not shown). These results indicate that Epac is an important mediator of the glucose-induced cAMP effect on insulin secretion.

cAMP Dependence of Manifest Glucose-induced Pulsatile Insulin Secretion Is Mediated by Epac2

In contrast to the early glucose response, the established pulsatile insulin secretion was not reduced by inhibitors of PKA. Thus, after treatment with Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (100 μm), KT5720 (2 μm), or H89 (10 μm) the amplitudes of the PIP3 oscillations were unaltered or even slightly increased, reaching 97 ± 4% (n = 38), 125 ± 10% (n = 35; p < 0.05), and 114 ± 6% (n = 27; p < 0.05) of control, respectively (Fig. 5, A–C). However, inhibition of adenylyl cyclases with 50 μm DDA or 400 μm SQ22536 reversibly suppressed the glucose-induced PIP3 response to 56 ± 5% (n = 39; p < 0.001) and 71 ± 4% (n = 51; p < 0.001) of control, respectively (Fig. 5, D–F). The action of cAMP is probably mediated by Epac because the agonist 007-AM restored the PIP3 response in cells treated with DDA or SQ22536 (Fig. 5, D–F). Similar results were obtained from the rat-derived β-cell line INS-1(832/13) (not shown). In addition, 007-AM restored spontaneously fading PIP3 oscillations in some glucose-stimulated cells (Fig. 5G).

FIGURE 5.

cAMP dependence of already established pulsatile insulin release in response to glucose is primarily mediated by Epac. A and B, evanescent wave microscopy recordings of glucose-stimulated PIP3 oscillations in a GFP4-Grp1-expressing MIN6 β-cell during inhibition of PKA with 2 μm KT5720 (A) (n = 35) or Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS (B) (n = 38). C, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the effect of different PKA inhibitors on the average PIP3 oscillation amplitudes. D and E, glucose-induced PIP3 responses are suppressed after inhibition of adenylyl cyclases with 50 μm DDA (D) (n = 39) or 400 μm SQ22536 (E) (n = 51), but in both cases the responses are partially restored by 1 μm Epac-selective activator 007-AM. F, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the effects of adenylyl cyclase inhibitors and 007-AM on the average PIP3 oscillation amplitude expressed in relation to the 11 mm glucose control. G, restoration of glucose-induced PIP3 oscillations in cells where the oscillations had spontaneously faded by application of 1 μm 007-AM (n = 10). ***, p < 0.001 compared with 11 mm glucose alone; #, p < 0.001 compared with 11 mm glucose + DDA and 007-AM.

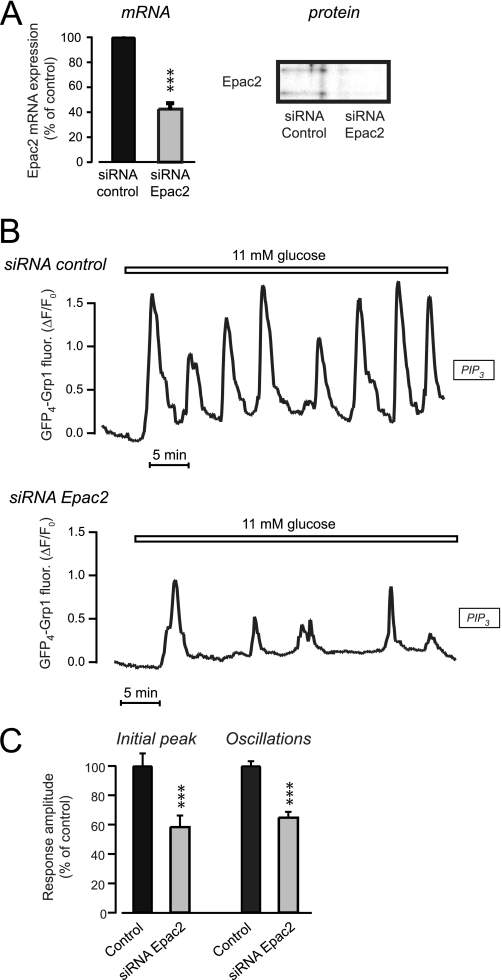

To pinpoint the role of Epac further, we next knocked down the Epac2 isoform. Treatment of the cells with 100 nm siRNA directed against Epac2 reduced the corresponding mRNA levels to 40% after 24 h compared with cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 6A). The knockdown of Epac2 protein was verified with Western blotting of whole cell extracts after 72 h (Fig. 6A). After Epac2 knockdown only 13% (n = 71) of cells responded to 007-AM with PIP3 elevation as compared with 66% (n = 59) in control siRNA treated cells (p < 0.001; data not shown). The glucose-induced PIP3 response was also markedly suppressed after Epac2 knockdown and the amplitude of both the initial and subsequent oscillations reached only 60% of control (n = 72–82 cells, p < 0.01; Fig. 6, B and C).

FIGURE 6.

Down-regulation of Epac2 expression suppresses glucose-induced pulsatile insulin secretion. A, Epac2 mRNA and protein expression in MIN6 cells detected with real-time PCR and Western blotting 24 h (mRNA) or 72 h (protein) after treatment with 100 nm siRNA targeted to Epac2 or luciferase as control. B, evanescent wave microscopy recording of membrane PIP3 concentration during elevation of the glucose concentration from 3 to 11 mm in single GFP4-Grp1-expressing MIN6 β-cells treated with 100 nm control (n = 82) or Epac2 siRNA (n = 72). C, means ± S.E. (error bars) of the amplitudes of the initial glucose-induced PIP3 peak and the average for the subsequent oscillations. ***, p < 0.001 for difference from control.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that cAMP is important for both initiating and maintaining pulsatile insulin release from glucose-stimulated MIN6 β-cells. During initiation of secretion, PKA activity is required to coordinate Ca2+ and cAMP elevations temporally, thereby allowing Epac to amplify the Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. However, PKA is also important for establishing subsequent pulsatile secretion. In contrast, already established pulsatile insulin secretion is maintained independently of PKA activity, and the cAMP dependence is mediated primarily by Epac2.

Similar to two-photon excitation imaging studies of the exocytosis in intact pancreatic islets (31), the present data indicate that PKA is involved primarily during early glucose-induced insulin secretion. Although voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels are substrates for PKA (25), PKA inhibitors did not suppress secretion by inhibiting the glucose-induced [Ca2+]i response. Neither did PKA inhibition interfere with the glucose-induced elevation of [cAMP]pm. Several proteins involved in insulin granule exocytosis are targets for PKA (25, 42), and PKA has been found to amplify exocytosis downstream of granule priming in a process regulated by ATP (28). On the other hand, we did not observe any effect of PKA inhibition on KCl depolarization-induced insulin secretion, which supposedly reflects exocytosis of primed, readily releasable granules (39). This observation is in line with results from membrane capacitance measurements showing that PKA has little effect on the readily releasable pool of granules (26).

Basal PKA activity seems to be a prerequisite for concomitant elevation of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm. Thus, after inhibition of PKA, the glucose-induced elevation of [Ca2+]pm and insulin secretion preceded the rise of [cAMP]pm. It is noteworthy that both the channel-forming Kir6.2 and the regulatory SUR1 subunit of the KATP channel are PKA substrates and that phosphorylation has been reported to increase channel activity (40, 41). Decreased KATP channel phosphorylation therefore likely explains the accelerated depolarization and earlier secretory response to glucose stimulation after PKA inhibition. However, there was no change in the timing of the cAMP elevation. This observation underscores that Ca2+ and cAMP are independently regulated in β-cells. Coordination of the Ca2+ and cAMP signals seems to be required for an optimal exocytosis response. An interesting possibility is that the reduced insulin secretion after inhibition of PKA is caused by temporal dissociation of the messenger signals, such that Ca2+ triggers exocytosis before the amplifying cAMP signal is manifested (Fig. 7). In support of this idea, we found that the initial secretory response was reduced when the KATP channel antagonist tolbutamide was used to induce precocious depolarization in glucose-stimulated MIN6 cells. Moreover, PKA inhibitors were without effect after synchronization of Ca2+ and cAMP elevations by washout of the KATP channel agonist diazoxide in the presence of 11 mm glucose.

FIGURE 7.

Model for the effect of PKA and Epac on glucose-induced pulsatile insulin secretion. Under control conditions, elevation of the glucose concentration triggers after a delay concomitant rises of [Ca2+]pm (red trace) and [cAMP]pm (black trace), which are followed by an increase of membrane PIP3 (green trace), reflecting the more pronounced initial peak of insulin secretion. During subsequent pulsatile secretion, [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm elevations slightly precede the rises of PIP3. When PKA is inhibited, the initial delay for increase of [Ca2+]pm is shortened. Moreover, The Ca2+-triggered rise of PIP3 is less pronounced than under control conditions and occurs before the elevation of [cAMP]pm. In contrast, inhibition of PKA during manifested pulsatile secretion does not alter the responses. Inactivation of Epac does not affect the glucose-induced [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm signals, but lowers the amplitude of both the first peak and the subsequent PIP3 responses.

Whereas basal PKA activity ascertains concomitant elevations of Ca2+ and cAMP, the cAMP effect is largely mediated by Epac because activation of this protein compensated for most of the suppressive effect of PKA inhibitors on glucose initiation of insulin secretion. However, additional mechanisms may be involved because not only the initial secretory response to glucose but also the subsequent development of pulsatile insulin release were compromised by PKA inhibition.

Epac2 is the major PKA-independent cAMP effector in islet cells, and it was recently reported that Epac2 knock-out mice show reduced cAMP amplification of glucose-induced insulin exocytosis (24). Epac2 has been implicated in the rapid cAMP-dependent potentiation of exocytosis in β-cells, whereas PKA is supposed to mediate a slower effect on secretion (26). Epac has also been reported to recruit insulin granules to the plasma membrane (24, 43) and together with PKA to stimulate granule-granule fusion events (43). Although it has been proposed that Epac primarily regulates exocytosis of small synaptic-like vesicles rather than insulin-containing dense core vesicles (44), our results based on the autocrine effect of secreted insulin favor the latter alternative. We now observed that both the initial peak of glucose-stimulated insulin release and the subsequent pulsatile secretion rely on a PKA-independent cAMP effector. The involvement of Epac was verified by two independent sets of experiments. First, pulsatile secretion perturbed by adenylyl cyclase inhibitors was restored by an Epac activator. Second, down-regulation of Epac2 expression with siRNA suppressed both the initial PIP3 response and the subsequent oscillations. However, the mechanisms of Epac2 action are not entirely clear. In addition to activating the small GTPase Rap1, which recently was found to play an important role in cAMP-potentiated exocytosis in β-cells (24), it is possible that Epac acts via mechanism(s) involving the SUR1 subunit of the KATP channel and/or the exocytosis proteins Rim2, Piccolo (45), and SNAP-25 (32).

In summary, we found that temporal coordination of [Ca2+]pm and [cAMP]pm signals are important for optimal glucose-induced insulin secretion from individual β-cells. Although initiation of glucose-stimulated secretion involves both PKA- and Epac-dependent mechanisms, the cAMP dependence of established pulsatile insulin secretion is mediated primarily by Epac2. Because type 2 diabetes is characterized by loss of glucose-stimulated first-phase insulin secretion (46) and perturbation of pulsatile secretion (47), clarification of the underlying Ca2+ and cAMP signaling events is important for understanding and correcting the defective β-cell function in this disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Johannes Bos for generous gifts of 007-AM and Epac2 antibodies; Cobolt AB, Stockholm, for collaboration regarding the Zouk UV laser; and Ing-Marie Mörsare for skillful technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Åke Wiberg Foundation, the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/MSD, the Family Ernfors Foundation, Harald and Greta Jeanssons Foundations, the Magnus Bergvall Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Swedish Diabetes Association, and the Swedish Research Council Grants 32X-14643, 32BI-15333, 32P-15439, and 12X-6240.

- KATP channel

- ATP-sensitive K+ channel

- [Ca2+]i

- cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration

- [Ca2+]pm

- cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration beneath the plasma membrane

- [cAMP]pm

- cAMP concentration beneath the plasma membrane

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- DDA

- 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine

- Epac

- exchange protein directly activated by cAMP IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- PH

- Pleckstrin homology

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- 007

- 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyladenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- Rp-8-CPT-cAMPS

- 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphorothioate, Rp-isomer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henquin J. C. (2000) Diabetes 49, 1751–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tengholm A., Gylfe E. (2009) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 297, 58–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henquin J. C. (2009) Diabetologia 52, 739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratanova-Tochkova T. K., Cheng H., Daniel S., Gunawardana S., Liu Y. J., Mulvaney-Musa J., Schermerhorn T., Straub S. G., Yajima H., Sharp G. W. (2002) Diabetes 51, Suppl. 1, S83–S90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rorsman P., Eliasson L., Renström E., Gromada J., Barg S., Göpel S. (2000) News Physiol. Sci. 15, 72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliasson L., Renström E., Ding W. G., Proks P., Rorsman P. (1997) J. Physiol. 503, 399–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grapengiesser E., Gylfe E., Hellman B. (1988) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 151, 1299–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergsten P., Grapengiesser E., Gylfe E., Tengholm A., Hellman B. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 8749–8753 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilon P., Shepherd R. M., Henquin J. C. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 22265–22268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian W. J., Peters J. L., Dahlgren G. M., Gee K. R., Kennedy R. T. (2004) BioTechniques 37, 922–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Idevall-Hagren O., Tengholm A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39121–39127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michael D. J., Xiong W., Geng X., Drain P., Chow R. H. (2007) Diabetes 56, 1277–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentki M., Matschinsky F. M. (1987) Physiol. Rev. 67, 1185–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furman B., Pyne N., Flatt P., O'Harte F. (2004) J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 56, 1477–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gromada J., Brock B., Schmitz O., Rorsman P. (2004) Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 95, 252–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellman B., Idahl L. Å., Lernmark Å., Täljedal I. B. (1974) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 71, 3405–3409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charles M. A., Fanska R., Schmid F. G., Forsham P. H., Grodsky G. M. (1973) Science 179, 569–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grill V., Cerasi E. (1973) FEBS Lett. 33, 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuit F. C., Pipeleers D. G. (1985) Endocrinology 117, 834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landa L. R., Jr., Harbeck M., Kaihara K., Chepurny O., Kitiphongspattana K., Graf O., Nikolaev V. O., Lohse M. J., Holz G. G., Roe M. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31294–31302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyachok O., Idevall-Hagren O., Sågetorp J., Tian G., Wuttke A., Arrieumerlou C., Akusjärvi G., Gylfe E., Tengholm A. (2008) Cell Metab. 8, 26–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones P. M., Persaud S. J. (1998) Endocr. Rev. 19, 429–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leech C. A., Holz G. G., Chepurny O., Habener J. F. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 278, 44–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibasaki T., Takahashi H., Miki T., Sunaga Y., Matsumura K., Yamanaka M., Zhang C., Tamamoto A., Satoh T., Miyazaki J., Seino S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19333–19338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seino S., Shibasaki T. (2005) Physiol. Rev. 85, 1303–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renström E., Eliasson L., Rorsman P. (1997) J. Physiol. 502, 105–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eliasson L., Ma X., Renström E., Barg S., Berggren P. O., Galvanovskis J., Gromada J., Jing X., Lundquist I., Salehi A., Sewing S., Rorsman P. (2003) J. Gen. Physiol. 121, 181–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi N., Kadowaki T., Yazaki Y., Ellis-Davies G. C., Miyashita Y., Kasai H. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 760–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persaud S. J., Jones P. M., Howell S. L. (1990) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 173, 833–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris T. E., Persaud S. J., Jones P. M. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232, 648–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatakeyama H., Kishimoto T., Nemoto T., Kasai H., Takahashi N. (2006) J. Physiol. 570, 271–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vikman J., Svensson H., Huang Y. C., Kang Y., Andersson S. A., Gaisano H. Y., Eliasson L. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297, E452–E461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimoto K., Shibasaki T., Yokoi N., Kashima Y., Matsumoto M., Sasaki T., Tajima N., Iwanaga T., Seino S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50497–50502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyazaki J., Araki K., Yamato E., Ikegami H., Asano T., Shibasaki Y., Oka Y., Yamamura K. (1990) Endocrinology 127, 126–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R. Y. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dyachok O., Isakov Y., Sågetorp J., Tengholm A. (2006) Nature 439, 349–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klarlund J. K., Guilherme A., Holik J. J., Virbasius J. V., Chawla A., Czech M. P. (1997) Science 275, 1927–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frech M., Andjelkovic M., Ingley E., Reddy K. K., Falck J. R., Hemmings B. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 8474–8481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olofsson C. S., Göpel S. O., Barg S., Galvanovskis J., Ma X., Salehi A., Rorsman P., Eliasson L. (2002) Pflügers Arch. 444, 43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Béguin P., Nagashima K., Nishimura M., Gonoi T., Seino S. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4722–4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin Y. F., Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 942–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lester L. B., Faux M. C., Nauert J. B., Scott J. D. (2001) Endocrinology 142, 1218–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwan E. P., Gao X., Leung Y. M., Gaisano H. Y. (2007) Pancreas 35, e45–e54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatakeyama H., Takahashi N., Kishimoto T., Nemoto T., Kasai H. (2007) J. Physiol. 582, 1087–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shibasaki T., Sunaga Y., Fujimoto K., Kashima Y., Seino S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7956–7961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosker J. P., Rudenski A. S., Burnett M. A., Matthews D. R., Turner R. C. (1989) Metabolism 38, 767–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang D. A., Matthews D. R., Burnett M., Turner R. C. (1981) Diabetes 30, 435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]