Abstract

Many experimental and clinical studies suggest a relationship between enhanced angiotensin II release by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. The atherosclerosis-enhancing effects of angiotensin II are complex and incompletely understood. To identify anti-atherogenic target genes, we performed microarray gene expression profiling of the aorta during atherosclerosis prevention with the ACE inhibitor, captopril. Atherosclerosis-prone apolipoprotein E (apoE)-deficient mice were used as a model to decipher susceptible genes regulated during atherosclerosis prevention with captopril. Microarray gene expression profiling and immunohistology revealed that captopril treatment for 7 months strongly decreased the recruitment of pro-atherogenic immune cells into the aorta. Captopril-mediated inhibition of plaque-infiltrating immune cells involved down-regulation of the C-C chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9). Reduced cell migration correlated with decreased numbers of aorta-resident cells expressing the CCR9-specific chemoattractant factor, chemokine ligand 25 (CCL25). The CCL25-CCR9 axis was pro-atherogenic, because inhibition of CCR9 by RNA interference in hematopoietic progenitors of apoE-deficient mice significantly retarded the development of atherosclerosis. Analysis of coronary artery biopsy specimens of patients with coronary artery atherosclerosis undergoing bypass surgery also showed strong infiltrates of CCR9-positive cells in atherosclerotic lesions. Thus, the C-C chemokine receptor, CCR9, exerts a significant role in atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Lymphocyte, Macrophage, Peptide Hormones, Angiotensin II

Introduction

Several clinical studies show that pharmacological inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system could mediate atheroprotection (1–4). In agreement with those clinical data, experimental studies demonstrated a causal relationship between angiotensin II release by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE),2 the angiotensin II AT1 receptor, and the development of atherosclerosis because genetic inactivation of either ACE or the AT1 receptor prevents atherosclerosis development in various animal models of atherosclerosis (5, 6). Likewise, inhibition of angiotensin II activity by ACE inhibitors or AT1 receptor antagonists is curative in such animal models of atherosclerosis (7, 8).

In view of the major anti-atherosclerotic effects of ACE inhibitors and AT1 antagonists, many studies investigated mechanisms that could contribute to atheroprotection upon angiotensin II inhibition. The effects of angiotensin II in atherosclerosis are complex involving actions on circulating blood cells and arterial smooth muscle cells as major targets (9–11). Established pro-atherogenic effects of angiotensin II on smooth muscle cells are related to a phenotype transformation from contractile to synthetic (11). The effects of angiotensin II on circulating immune cells are less clear, although, gene inactivation studies clearly demonstrated the involvement of circulating blood and progenitor cells in the atherosclerosis-enhancing activity of ACE and the AT1 receptor (9).

Several studies revealed that AT1 receptor-stimulated signaling enhances the pro-atherogenic potential of monocytes and macrophages by sustaining monocyte/macrophage migration into the subendothelial layer of the arterial wall, where transformation into foam cells occurs (9, 10). In addition to macrophages, the AT1 receptor may also exert effects on T lymphocytes by supporting T lymphocyte migration into the perivascular tissue (12). Infiltrating T cells also play a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis as demonstrated by studies with animal models and patients (13, 14). However, the full impact of angiotensin II on peripheral immune cells in the course of atherosclerosis development is still not understood.

To further analyze the role of immune cells in the atherogenic process, and the anti-atherogenic potential of angiotensin II inhibition, we performed microarray gene expression profiling of the aorta as the target organ of atherosclerosis. As a prototypic ACE inhibitor we chose captopril with established anti-atherosclerotic actions in vivo, in various animal models (7, 10, 15), and patients (16). We report here that inhibition of angiotensin II generation and atherosclerosis development by captopril in hypercholesterolemic apoE-deficient mice led to a profound change of the aortic immune cell infiltrate, and down-regulated the chemoattractant C-C chemokine receptor type 9 (CCR9), with its specific ligand, C-C motif chemokine 25 (CCL25).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal Experiments

For the study, 4–6-week-old apoE-deficient mice on a C57BL/6J background, and non-transgenic C57BL/6J controls were used. Mice were kept on a 12-h light/12-h dark regime, had free access to food and water, and were fed a standard rodent chow containing 7% fat and 0.15% cholesterol (AIN-93-based diet). As indicated, apoE-deficient mice received captopril in drinking water (20 mg/kg; prepared fresh every day) for 7 months, or the angiotensin II AT1 receptor-specific antagonist, losartan (30 mg/kg). At an age of 32–34 weeks, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100/10 mg/kg), and perfused intracardially with sterile phosphate-buffered saline. The aorta was isolated, rapidly dissected free of adherent adipose tissue, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, or processed for further use. Total plasma cholesterol was determined using a standard enzymatic kit, and systolic blood pressure was measured by the tail-cuff method (10). Atherosclerotic lesion area of the aortic root was quantified by computerized image analysis as described (10). Mouse peripheral blood mononuclear cells and monocytes were isolated from heparin-anticoagulated blood diluted with phosphate-buffered saline by density gradient centrifugation through Ficoll-Paque or Opti-prep followed by plastic adherence or by Nycoprep density gradients (10). Monocyte purity was >80% as determined by immunofluorescence staining of cell-specific antigens (10). Monocytes were cultivated as described (10). All solutions and chemicals used in monocyte isolation and activation were endotoxin-free (endotoxin <0.008 ng/ml). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the NIH guidelines, and were reviewed and approved by the local committees on animal care and use (University of Zurich and Hamburg).

Patients

The study was performed with coronary artery biopsy specimens obtained from 15 patients with coronary artery disease undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery (diseased vessels 2.3 ± 0.5; age 51 ± 6 years; 9 males). All the patients had a recent history of an acute coronary syndrome (3 weeks to 3 months prior to bypass surgery). Coronary artery biopsy specimens without atherosclerotic lesions as confirmed by the absence of Oil-red O-stained atherosclerotic lesions served as controls. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Ain Shams University, Cairo).

Bone Marrow Transplantation

For lentiviral-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) inhibition of CCR9 in hematopoietic progenitors, transduced bone marrow cells isolated from apoE-deficient donors (1 × 106) were injected into the tail vein of irradiated 11–12-week-old, syngeneic apoE-deficient recipients as described previously (10). For RNA interference, lentiviral constructs with RNA polymerase II promoter-driven expression of micro-RNAs targeting CCR9 (nucleotides 359–379), or β-galactosidase as a control (nucleotides 1298–1318) were used. Generation of high-titer lentiviruses and murine hematopoietic cell transduction were performed essentially as described (10, 17). Four months after bone marrow transplantation, mice were sacrificed, blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and mononuclear cells were isolated for assessment of CCR9 protein levels (10). Persistent reduction of CCR9 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (18) was maintained throughout the observation period of 4 months after transplantation.

Microarray Gene Expression Profiling

Microarray gene expression analysis of the aorta was performed essentially as described previously (19). Briefly, total RNA of the dissected aortas was isolated with the RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen). Procedures for cDNA synthesis, labeling, and hybridization were carried out according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Affymetrix). For hybridization, 15 μg of fragmented cRNA were incubated with the chip (Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse genome MG430 2.0 Array) in 200 μl of hybridization solution in a Hybridization Oven 640 (Affymetrix) at 45 °C for 16 h. GeneChips were washed and stained using Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 according to the GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual (revision 5). Microarrays were scanned with the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 7G, and the signals were processed with a target value of 200 using GCOS (version 1.4, Affymetrix). All microarray gene expression data are available at NCBI GEO data base accession number GSE19286.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting: monoclonal rat anti-CD8a antibodies (BD Pharmingen), rabbit anti-CD22 antibodies (BD Pharmingen), monoclonal rat anti-MOMA-2 antibodies (Serotec), affinity-purified rabbit anti-AT1 receptor antibodies raised against an antigen corresponding to positions 306–359 of the mouse AT1A receptor sequence (10), affinity-purified rabbit/rat anti-CCR9 antibodies raised against recombinant CCR9 protein, or an antigen encompassing amino acids 321–351 of the human or mouse CCR9 sequence, respectively, rabbit/rat anti-mCCL25 antibodies raised against an antigen encompassing amino acids 1–27 of the mouse CCL25 sequence, or recombinant mouse CCL25. Recombinant CCL25 was produced in Escherichia coli and purified similarly as described (20), and the CCR9 protein was expressed in and purified from Spodoptera frugiperda cells infected with a recombinant baculovirus encoding CCR9 as detailed previously (21). Immunization of antigens (1 mg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline mixed 1:1 with complete Freund's adjuvant was done according to standard protocols followed by booster injections in incomplete Freund's adjuvant 2 weeks after the first injection and monthly thereafter (17). Immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry were routinely used to determine and confirm cross-reactivity of the antibodies with the respective proteins.

Immunohistology and Immunofluorescence

For immunohistology, cryosections or paraffin sections of the aortic sinus region (10 μm, taken at 50-μm intervals for analyses, 10–15 sections per set) were used (10, 17). Immunohistological detection of CCR9 and CCL25 was performed with affinity-purified, polyclonal antibodies pre-absorbed to mouse or human tissue similarly as described (10, 17). All sections were imaged with a Leica DMI6000 microscope equipped with a DFC420 camera.

Immunofluorescence localization studies were performed with cryosections (10 μm) of post-fixed and frozen aortas, which were obtained from 8-month-old apoE-deficient mice. For co-localization of CCR9 and CCL25, affinity-purified rabbit anti-CCL25 antibodies and rat anti-CCR9 antibodies were applied (dilution 1:4000), followed by secondary antibodies or F(ab)2 fragments of the antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 546, respectively (dilution 1:5000), and counterstaining with DAPI. Sections were imaged with a Leica DMI6000 microscope and a Leica (TCS) confocal laser microscope.

Immunoblot Detection of Proteins

Immunoblot detection of proteins was performed as described previously with affinity-purified antibodies pre-absorbed to mouse or human proteins, respectively (10, 17). Bound antibody was visualized with F(ab)2 fragments of enzyme-coupled secondary antibodies, or by enzyme-coupled protein A followed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise stated, data are expressed as mean ± S.D. To determine significance between two groups, we made comparisons using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. p values of <0.05 were considered significant unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Captopril Inhibits Atherosclerosis Development of apoE-deficient Mice

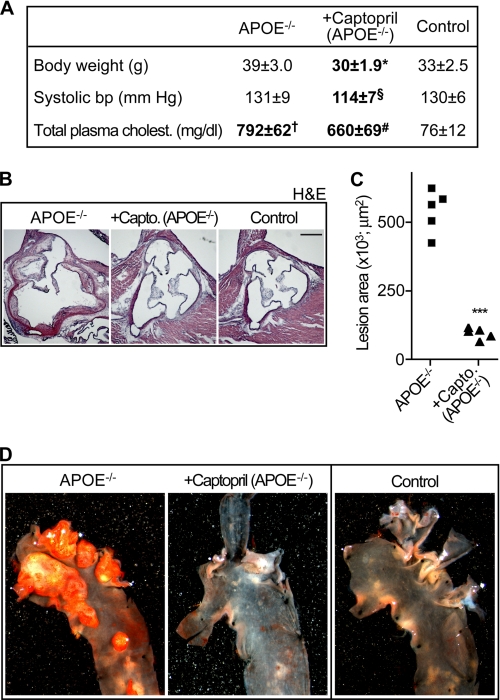

To assess the effect of ACE inhibition on atherosclerosis development, atherosclerosis-prone, 4–6-week-old apoE-deficient mice were treated for 7 months with the ACE inhibitor, captopril, in drinking water. After 7 months, captopril-treated mice had a modest decrease in body weight and blood pressure relative to age-matched, non-treated apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 1A). Those observations are in agreement with established effects of ACE and ACE inhibitors, respectively (10, 22). In contrast, captopril did not affect total plasma cholesterol levels of apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Captopril inhibits atherosclerosis development of apoE-deficient mice. A, characteristic parameters of the three study groups, i.e. untreated apoE-deficient (APOE−/−), captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril, APOE−/−), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (Control) mice (age 32–34 weeks). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 5 mice/group; *, p < 0.01 (APOE−/− versus Captopril); §, p < 0.05 (APOE−/− versus Captopril); †, p < 0.05 (APOE−/− versus Control); #, p < 0.05 (Captopril versus Control); analysis of variance with Dunn's multiple comparison test. B, representative hematoxylin-eosin (H & E)-stained sections representing the mean aortic root lesion area of 32–34-week-old apoE-deficient (APOE−/−, left panel), captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Capto., apoE−/−, middle panel), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (Control; right panel) mice demonstrate that captopril suppressed atherosclerotic plaque formation of apoE-deficient mice (bar, 500 μm). C, quantification of the atherosclerotic lesion area in the aortic root of 32–34-week-old untreated apoE-deficient (APOE−/−) and captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Capto., APOE−/−) mice; n = 5 mice/group; ***, p < 0.0001. D, representative Oil-red O-staining of atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic arch of an untreated apoE-deficient mouse (APOE−/−, left panel) relative to captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril, APOE−/−, middle panel) and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (Control, right panel) mice.

Concomitantly, captopril treatment largely prevented the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic root of apoE-deficient mice as evidenced by histological analysis (Fig. 1B, middle versus left panel). As a control, the aortic root of non-transgenic C57BL/6J mice was lesion-free (Fig. 1B, right panel). Quantification of the plaque area demonstrated that captopril treatment had reduced the mean aortic root lesion area by 79 ± 9% relative to untreated apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 1C). Altogether, these findings confirm that captopril efficiently inhibits atherosclerosis development of apoE-deficient mice (7, 10).

Microarray Analysis of Atherosclerosis Prevention by Captopril

To assess the mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis prevention mediated by captopril, we performed microarray gene expression profiling of the aorta of 8-month-old apoE-deficient mice with overt atherosclerosis relative to age-matched apoE-deficient mice treated for 7 months with the ACE inhibitor, captopril (Fig. 1D, middle versus left panel). As a control, we used non-transgenic C57BL/6J mice without atherosclerosis (Fig. 1D, right panel). Oil-red O staining of representative aortas of the three study groups confirmed that captopril treatment for 7 months prevented the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the aorta of apOE-deficient mice, whereas age-matched apoE-deficient mice showed a high plaque load of the aortic arch (Fig. 1D, middle versus left panel).

For microarray analysis, total aortic RNA isolated of the three study groups were used, i.e. untreated apoE-deficient, captopril-treated apoE-deficient, and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice. Data obtained after chip scanning revealed uniform quality of the microarrays as assessed by the comparable number of probe sets present, and the 3′/5′ ratio of probe sets detecting glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and β-actin (GEO data base number GSE19286).

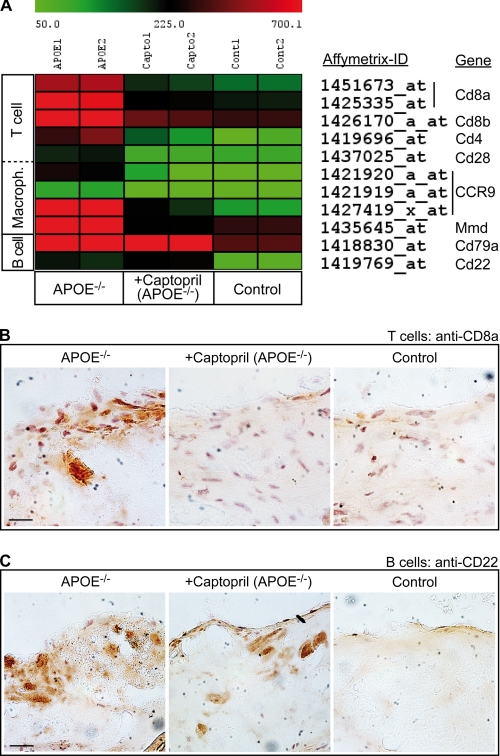

Microarray Analysis Reveals Infiltrating Immune Cells in the Aorta of ApoE-deficient Mice

After data normalization, microarray data were evaluated. Because ACE inhibitors target inflammatory immune cells (9, 10), we determined the impact of captopril on immune cell recruitment. To identify microarray probe sets specific of aorta-infiltrating immune cells, we applied a stringent filtering strategy (19). Aortic probe sets of captopril-treated apoE-deficient mice were selected displaying: (i) a significantly different signal compared with untreated apoE-deficient mice (*, p < 0.05), (ii) a more than 50% reduction of signal intensity relative to untreated apoE-deficient mice, (iii) membrane localization according to gene ontology analysis, and (iv) immune cell specificity. The very stringent approach identified only 9 differentially expressed probe sets, which showed effects of captopril on the infiltration of the aorta with immune cells (Fig. 2A). Notably, captopril normalized the increased aortic expression of T cell- and macrophage-specific marker proteins of apoE-deficient mice, i.e. Cd8a, Cd8b, Cd4, Cd28, Ccr9, and Mmd (monocyte to macrophage differentiation-associated) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, B lymphocyte-specific markers, such as Cd79a and Cd22, were not significantly affected by captopril (Fig. 2A). As a control, atherosclerosis development of apoE-deficient mice was accompanied by a strong up-regulation of all mononuclear cell-specific probe sets relative to non-transgenic C57BL/6J controls, i.e. T cell-, macrophage-, and B cell-specific marker proteins (Fig. 2A). Thus, the microarray approach was capable to detect aorta-infiltrating immune cells in the course of atherosclerosis development.

FIGURE 2.

Microarray analysis reveals infiltrating immune cells in the aorta of apoE-deficient mice. A, normalized signal intensity values of differentially expressed probe sets detecting immune cell-specific markers in the aortas of captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril, APOE−/−) relative to untreated apoE-deficient (APOE−/−) mice are presented as a heat map centered to the median value. Probe sets of captopril-treated mice, which showed (i) a significantly different signal intensity value relative to untreated apoE-deficient mice (p < 0.05), (ii) a more than 50% reduction of signal intensity relative to untreated apoE-deficient mice, (iii) membrane localization, and (iv) immune cell specificity are listed. As a control, the B cell-specific probe sets of Cd79a and Cd22 were also included, which are not different between captopril-treated and untreated apoE-deficient mice. For comparison, all immune cell markers were significantly different between non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Control) and apoE-deficient mice (p < 0.05). B, immunohistology analysis of infiltrating T cells in aortic root sections of an apoE-deficient (APOE−/−, left panel), captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril, APOE−/−, middle panel), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (Control, right panel) mouse was performed with anti-CD8a antibodies. C, detection of infiltrating B cells by immunohistology of aortic root sections of an apoE-deficient (APOE−/−, left panel), captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril, apoE−/−, middle panel), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (Control, right panel) mouse was performed with CD22-specific (anti-CD22) antibodies (bar, 20 μm). Immunohistology data are representative of at least 3 different mice per group (B and C).

Captopril Suppresses Aortic T Cell Infiltration of ApoE-deficient Mice

To validate the microarray data regarding the observed effect of captopril on aortic T cell recruitment, we performed immunohistology analysis of the aortic sinus region. Immunostaining with antibodies specifically recognizing CD8a revealed that captopril significantly suppressed the infiltration of the aortic sinus region with CD8a-positive cells (Fig. 2B, middle versus left panel). As a control, non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice did not show substantial infiltration of the aorta with CD8a-positive cells compared with apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 2B, right versus left panel).

The CD8a positive cells did not stain positive for the dendritic cell-specific marker protein, CD11c (data not shown). In addition, the microarray data did not show a significant difference in the expression of Cd11c between untreated and captopril-treated apoE-deficient mice (cf. GSE19286).

Altogether, the data are compatible with the notion that captopril suppresses aortic T cell infiltration of apoE-deficient mice. Because T cells are considered pro-atherogenic (13), suppression of T cell migration may contribute to atherosclerosis prevention exerted by captopril.

Captopril Maintains the Presence of B Lymphocytes in the Aorta of Atherosclerosis-prone ApoE-deficient Mice

We also used immunohistology to validate the microarray data on B cell migration. In contrast to T cells, B lymphocytes are considered atheroprotective (23). In agreement with the microarray data, captopril treatment did not significantly reduce the presence of B cells in the aorta of apoE-deficient mice according to immunohistology analysis applying CD22-specific antibodies (Fig. 2C, middle versus left panel). As a control, B cells were largely absent in non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Fig. 2C, right versus left panel). Altogether, captopril treatment may sustain the migration of atheroprotective B cells into the aorta of atherosclerosis-prone apoE-deficient mice while suppressing the aortic infiltration with atherosclerosis-promoting T cells.

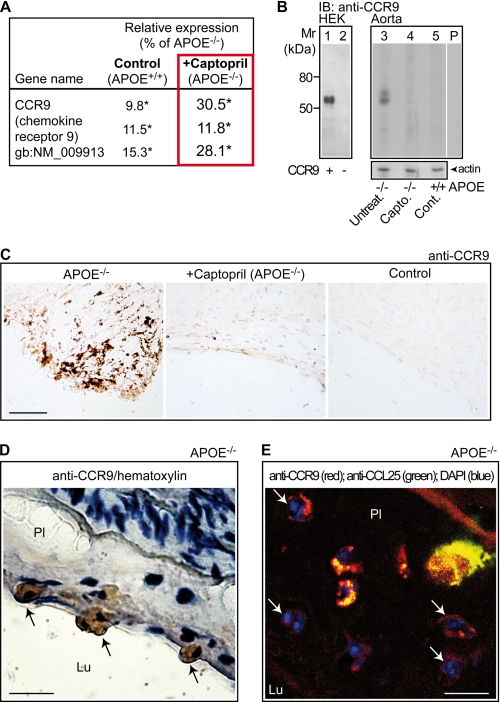

Captopril Suppresses the Recruitment of CCR9-positive Immune Cells into the Aorta of ApoE-deficient Mice

In addition to the lymphocyte markers for T and B cells, the microarray data revealed the strong up-regulation of three different probe sets detecting Ccr9 in the atherosclerotic aorta of apoE-deficient mice relative to non-transgenic controls (Figs. 2A and 3A). All three probe sets were substantially down-regulated by captopril treatment (Fig. 3A). Immunoblotting with CCR9-specific antibodies (Fig. 3B, lane 1 versus 2) confirmed the microarray data revealing a strong reduction of aortic CCR9 protein levels upon captopril treatment (Fig. 3B, lane 4 versus 3, and cf. Fig. 7D). As a control, non-transgenic control mice did not show significant CCR9 protein levels in the aorta (Fig. 3B, lane 5).

FIGURE 3.

Captopril suppresses the recruitment of CCR9-positive immune cells into the aorta of apoE-deficient mice. A, microarray data showing down-regulation of aortic Ccr9 expression of captopril-treated apoE-deficient mice (+Captopril; APOE−/−) relative to untreated apoE-deficient mice (APOE−/−). For comparison, the decreased signal intensities of the Ccr9-specific probe sets of non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Control; APOE+/+) are also presented. Relative expression values of the Ccr9-specific probe sets are presented as % of apoE−/−, i.e. 100% (*, p < 0.04). B, immunoblot (IB) detection of the CCR9 protein (IB, anti-CCR9) was performed with affinity-purified CCR9-specific antibodies on HEK cell membranes, transfected with (+) and without (−) a plasmid encoding CCR9 (lanes 1 and 2), and on aortic membranes isolated from an untreated apoE-deficient (APOE−/−; Untreat., lane 3), a captopril-treated apoE-deficient (APOE−/−; Capto., lane 4), and a non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (APOE+/+; Cont., lane 5) mouse, respectively. Immunoblot data are representative of 4 different mice/group. Lane P is a specificity control showing an immunoblot of aortic membranes from an apoE-deficient mouse and pre-absorption of the antibodies with the antigen used for immunization. The lower panel shows an immunoblot of β-actin demonstrating equal protein loading. C, immunohistology detection of CCR9 with affinity-purified CCR9-specific antibodies on aortic root sections of apoE-deficient (APOE−/−, left panel), captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril; APOE−/−, middle panel), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control (Control, right panel) mice (bar, 100 μm). D, immunohistology detection of CCR9-positive cells (marked by arrows) docking to the aortic intima (with atherosclerotic plaque, Pl) from the side of the aortic lumen (Lu) of an apoE-deficient mouse (APOE−/−). The aortic root section was counterstained with hematoxylin (bar, 20 μm). E, CCR9-positive cells in the aortic root section (with atherosclerotic plaque, Pl) of an apoE-deficient mouse (APOE−/−) were detected by immunofluorescence with affinity-purified, rat anti-CCR9 antibodies followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 546-labeled secondary antibodies (red). The presence of CCL25 was detected with affinity-purified, rabbit anti-CCL25 followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies (green). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows point to multinucleated CCR9-positive foam cells. Autofluorescence marks internal elastic lamina (bar, 20 μm). Immunohistology/immunofluorescence data are representative of at least 3 different mice/group (C–E).

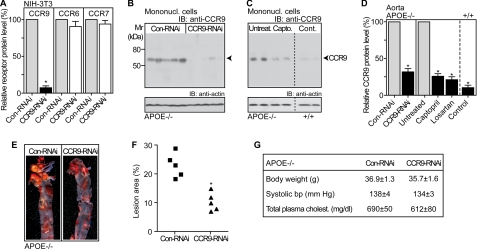

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of CCR9 in hematopoietic progenitors retards atherosclerosis development of apoE-deficient mice. A, immunoblot (IB) quantification of relative CCR9, CCR6, and CCR7 protein levels on membranes of the receptor-expressing NIH-3T3 cells transduced with a control lentivirus (Con-RNAi; 100%) or with lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of Ccr9 (CCR9-RNAi). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 4; *, p < 0.0001. B, immunoblot detection of CCR9 with affinity-purified anti-CCR9 antibodies (IB: anti-CCR9) on membranes of circulating mononuclear cells (Mononucl. cells) isolated from apoE-deficient mice (APOE−/−) with lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of Ccr9 in hematopoietic progenitors (CCR9-RNAi) relative to apoE-deficient mice transplanted with cells transduced with a control lentivirus (Con-RNAi); n = 5 mice/group. C, immunoblot detection of CCR9 (IB: anti-CCR9) on membranes of circulating mononuclear cells isolated from 28-week-old untreated apoE-deficient mice (Untreat., APOE−/−), captopril-treated apoE-deficient mice (Capto., APOE−/−), and untreated non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Cont., APOE+/+); n = 2 mice/group. B and C, lower panels show immunoblots of β-actin demonstrating equal protein loading (IB: anti-actin). D, quantification of relative aortic CCR9 protein levels of apoE-deficient mice (APOE−/−) with lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of CCR9 in hematopoietic progenitors (CCR9-RNAi) relative to apoE-deficient mice transplanted with cells transduced with a control lentivirus (Con-RNAi; 100%) by densitometric immunoblot scanning. As a control, aortic CCR9 protein levels were quantified of age-matched, untreated APOE-deficient mice (Untreated; 100%), captopril-treated APOE-deficient mice (Captopril, 4 months of treatment), losartan-treated apoE-deficient mice (Losartan, 4 months of treatment), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Control, APOE+/+). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 5 mice/group; *, p < 0.001. E, Oil-red O staining of the aorta revealed a significantly decreased atherosclerotic plaque area upon lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of Ccr9 in hematopoietic progenitors (CCR9-RNAi) relative to apoE-deficient mice receiving transplantation of cells transduced with a control lentivirus (Con-RNAi). F, quantification of the atherosclerotic lesion area was performed by quantitative image analysis of the Oil-red O-stained lesion area of the aorta. Data are reported as the percent of the aortic surface area covered by lesions of apoE-deficient mice with lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of Ccr9 in hematopoietic progenitors (CCR9-RNAi), and apoE-deficient mice receiving transplantation of control lentivirus-transduced cells (Con-RNAi); *, p < 0.001 (n = 5). G, body weight, systolic blood pressure, and total plasma cholesterol were not significantly different between 28-week-old apoE-deficient (APOE−/−) mice with lentiviral-mediated inhibition of CCR9 in hematopoietic progenitors (CCR9-RNAi), and apoE-deficient mice transplanted with cells transduced with a control lentivirus (Con-RNAi). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 5 mice/group.

CCR9 is expressed on various immune cells including T cells and macrophages (20, 24). Immunohistology was performed to identify the aorta-infiltrating cells, which were CCR9-positive. Immunohistology of aortic sinus sections with CCR9-specific antibodies showed localization of CCR9 on plaque-resident cells of the atherosclerotic aorta (Fig. 3C, left panel). CCR9-positive cells were strongly reduced by captopril treatment and virtually absent in non-transgenic C57BL/6J controls (Fig. 3C, middle and right panels).

Some CCR9-positive cells were docking to the atherosclerotic intima from the side of the aortic lumen suggesting that CCR9-positive cells could be derived from circulating immune cells (Fig. 3D, and cf. Fig. 4). As a control, significant staining of endothelial cells by CCR9-specific antibodies was not observed (data not shown).

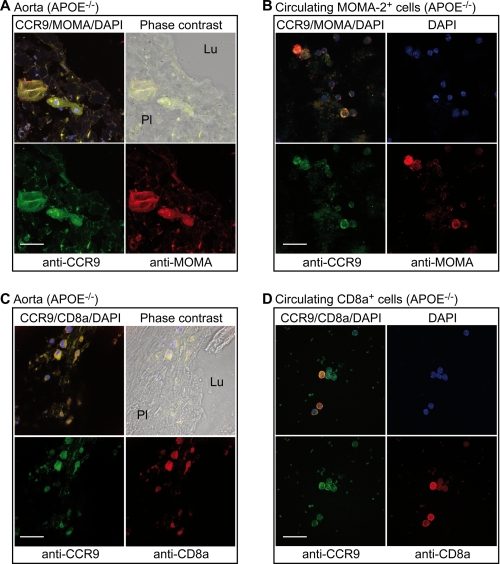

FIGURE 4.

CCR9 localization on plaque-resident macrophages and circulating monocytes. A, localization of CCR9 on MOMA-2-positive macrophages/foam cells of the aortic root of an apoE-deficient mouse (APOE−/−). Aortic lumen (Lu) and plaque area (Pl) are indicated on the phase-contrast image (right upper panel, overlay CCR9/MOMA-2). B, circulating MOMA-2-positive monocytes of apoE-deficient mice are also CCR9-positive. C, the CCR9 protein is localized on CD8a positive cells of the aortic root of apoE-deficient mice. Aortic lumen (Lu) and plaque area (Pl) are indicated on the phase-contrast image (right upper panel, overlay CCR9/CD8a/DAPI). D, circulating CD8a-positive cells are CCR9-positive. CCR9-positive cells were detected by immunofluorescence on aortic cryosections (A and C) or circulating cells (B and D) with affinity-purified, rabbit anti-CCR9 antibodies (anti-CCR9) followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibodies (green, A–D). The presence of the monocyte-macrophage-specific marker, MOMA-2, was detected with rat anti-MOMA-2 antibodies (anti-MOMA) followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 546-labeled secondary antibodies (red, A and B). CD8a-positive cells were identified by rat anti-CD8a antibodies (anti-CD8a) followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 546-labeled secondary antibodies (red, C and D). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue, A–D; bar, 20 μm). Immunofluorescence data are representative of at least 3 different mice.

Immunofluorescence was applied to determine the cellular localization of CCR9. Membrane-localized CCR9 was present on cells, which displayed characteristics of macrophages differentiating into foam cells with multiple cell nuclei (Fig. 3E). CCR9-positive cells in the atherosclerotic aortic intima of apoE-deficient mice were localized in close proximity to cells releasing the CCR9-specific chemoattractant, CCL25 (Fig. 3E). Thus, atherosclerotic plaques of apoE-deficient mice show CCR9-positive cells, and captopril treatment strongly reduced the recruitment of aorta-infiltrating CCR9-positive cells.

CCR9 Localization on Plaque-resident Macrophages and Circulating Monocytes

We next asked whether the plaque-resident CCR9-positive cells showed characteristics of macrophages as a major source of foam cells. Immunofluorescence studies revealed the co-localization of CCR9 with the monocyte/macrophage-specific marker, MOMA-2, on plaque-resident macrophages/foam cells of the aorta (Fig. 4A). In agreement with the migration of blood-derived monocytes into the inflamed aortic intima, circulating MOMA-2-positive monocytes of apoE-deficient mice also stained positive for the CCR9 protein (Fig. 4B). In contrast, circulating mononuclear cells of captopril-treated and non-transgenic control mice did not show significant CCR9 protein levels (cf. Figs. 6A and 7C). In addition to monocytes and macrophages, plaque-infiltrating and circulating CD8a+ T cells were also CCR9-positive (Fig. 4, C and D).

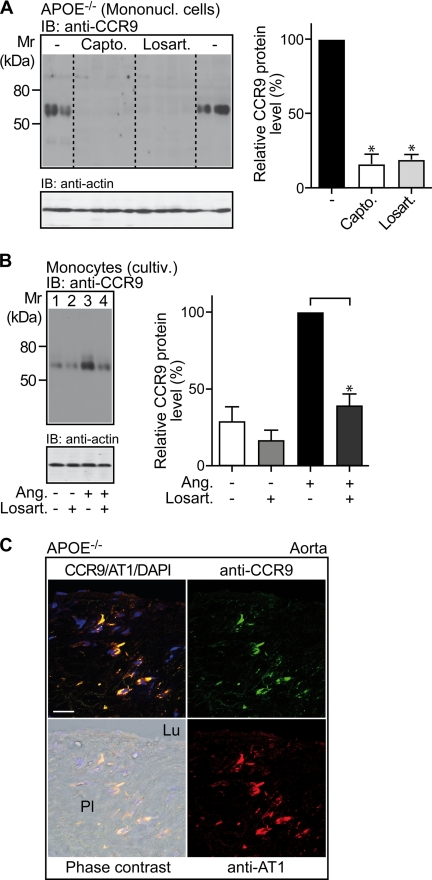

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of ACE-dependent angiotensin II AT1 receptor activation reduces CCR9 protein levels of circulating mononuclear cells. A, immunoblot (IB) detection of CCR9 (IB, anti-CCR9) on mononuclear cell membranes (Mononucl. cells) isolated from 32-week-old untreated apoE-deficient mice (−), captopril-treated (Capto.), and losartan-treated (Losart.) apoE-deficient mice (n = 4 mice/group). The lower panel is a control immunoblot of β-actin (IB: anti-actin) demonstrating equal protein loading. The right panel shows quantification of the relative CCR9 protein levels by densitometric immunoblot scanning (Untreated,−; 100%). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 4 mice/group; *, p < 0.001. B, immunoblot detection of CCR9 (IB, anti-CCR9) on cultivated monocytes (cultiv.) isolated from apoE-deficient mice. Cultivated monocytes were incubated for 30 h in the absence (−) or presence (+) of angiotensin II (Ang; 50 nm), and/or losartan (Losart.; 5 μm; added 30 min before angiotensin II) as indicated. The left panel shows a representative immunoblot, and the right panel shows quantification of the relative CCR9 protein levels by densitometric immunoblot scanning of three independent experiments (Ang,+; 100%). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 3; *, p < 0.01. C, immunofluorescence reveals co-localization of CCR9 and AT1 on plaque-resident cells of apoE-deficient mice. CCR9 was detected with affinity-purified, rat anti-CCR9 (anti-CCR9) antibodies followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled (green) secondary antibodies. Detection of the AT1 receptor was performed with affinity-purified anti-AT1 antibodies from rabbit (anti-AT1) followed by Alexa Fluor 546-labeled (red) secondary antibodies. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The lumen (Lu) and plaque (Pl) areas are indicated on the phase-contrast image (overlay CCR9/AT1/DAPI), bar, 20 μm. Immunofluorescence data are representative of 3 different mice.

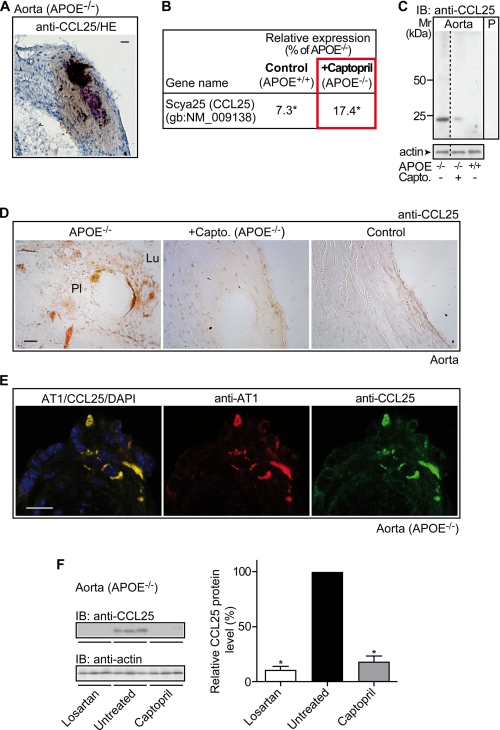

Captopril Reduces Plaque-resident CCL25-positive Cells

The C-C chemokine, CCL25, attracts CCR9-positive cells (20, 24). Immunohistology revealed the CCR9-specific chemoattractant, CCL25, in the atherosclerotic aortic root with advanced plaques adjacent to necrotic core areas (Fig. 5A). In agreement with immunohistology data, there was a significantly increased Ccl25 expression in the atherosclerotic aorta relative to non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, atherosclerosis prevention by captopril treatment largely suppressed the increase in aortic Ccl25 expression of apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 5B). Microarray data on Ccl25 expression in the atherosclerotic aorta were confirmed by immunoblotting with CCL25-specific antibodies (Fig. 5C).

FIGURE 5.

Captopril reduces plaque-resident CCL25-positive cells. A, immunohistology detection of CCL25 on an aortic root section of an apoE-deficient mouse (APOE−/−) was performed with affinity-purified anti-CCL25 antibodies (anti-CCL25) visualizing CCL25 adjacent to a necrotic center. Cell nuclei were stained with hematoxylin (HE; bar, 20 μm). B, microarray data reveal down-regulation of aortic Ccl25 expression by captopril treatment (+Captopril; APOE−/−) relative to untreated apoE-deficient (APOE−/−) mice. For comparison, the relative signal intensity of the Ccl25-specific probe set of non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Control, APOE+/+) is also presented. The relative expression values of the probe set are presented as % of apoE−/−, i.e. 100% (*, p ≤ 0.01). C, immunoblot detection of CCL25 with affinity-purified CCL25-specific antibodies (IB: anti-CCL25) in aortic tissue isolated from an untreated apoE-deficient mouse (−/−; −), a captopril-treated apoE-deficient mouse (−/−; +Capto.), or an untreated non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mouse (+/+; −). Lane P is a specificity control showing an immunoblot of aortic tissue from apoE-deficient mice and pre-absorption of the antibodies with the antigen used for immunization. The lower panel shows an immunoblot of β-actin demonstrating equal protein loading. The immunoblots are representative of 4 different mice/group. D, immunohistology detection of CCL25 with affinity-purified CCL25-specific antibodies (anti-CCL25) on aortic root sections of apoE-deficient (APOE−/−, left panel), captopril-treated apoE-deficient (+Captopril; APOE−/−, middle panel), and non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice (Control, right panel). Lumen (Lu) and plaque (Pl) area are indicated, bar, 20 μm. E, immunofluorescence detection of CCL25 on plaque-resident cells of an apoE-deficient mouse. CCL25 was detected with affinity-purified, rat anti-CCL25 antibodies followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled (green) secondary antibodies (left/right panels). The CCL25-positive cells co-localized with AT1, which was detected with affinity-purified, rabbit anti-AT1 antibodies followed by F(ab)2 fragments of Alexa Fluor 546-labeled (red) secondary antibodies (left/middle panels). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue, left panel) (bar, 20 μm). Immunohistology/immunofluorescence data are representative of at least 3 different mice/group (A, D, and E). F, immunoblot detection of CCL25 with affinity-purified CCL25-specific antibodies (IB, anti-CCL25) in aortic tissue isolated from losartan-treated (Losartan), untreated (Untreated), and captopril-treated (Captopril) apoE-deficient mice (n = 3 mice/group). The lower panel is a control immunoblot detecting β-actin (IB, anti-actin). The right panel shows quantification of the relative CCL25 protein levels by densitometric immunoblot scanning (Untreated, 100%). Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 3 mice/group; *, p < 0.0004.

Immunohistology revealed the CCL25 protein on plaque-infiltrating cells of the atherosclerotic aortic intima of apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 5D, left panel). Infiltration of the aortic intima with CCL25-positive cells was strongly reduced by captopril treatment (Fig. 5D, middle panel). As a control, the aortic intima of non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice did not show significant numbers of CCL25-positive cells (Fig. 5D, right panel). Thus, atherosclerosis development is accompanied by the appearance of CCL25 and its specific receptor, CCR9, on plaque-infiltrating cells of apoE-deficient mice. On the other hand, prevention of atherosclerosis development by captopril down-regulated the CCL25-CCR9 axis.

CCL25 Co-localizes with the Angiotensin II AT1 Receptor on Plaque-resident Cells

Enhanced activation of AT1 receptors by ACE-dependent angiotensin II generation is considered to be causally involved in atherogenesis (5–8, 10). To assess whether there could be a relationship between the AT1 receptor and plaque-infiltrating CCL25-positive cells, we performed immunofluorescence localization of AT1 and CCL25. Immunofluorescence data with AT1-specific and CCL25-specific antibodies, respectively, showed localization of the AT1 receptor on plaque-infiltrating CCL25-positve cells of apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 5E). This finding strongly suggests that AT1-stimulated signaling could directly modulate the expression of CCL25. Previous findings support such a conclusion demonstrating that AT1-mediated signaling triggers the expression of Egr-1 (early growth response protein 1) target genes such as Ccl25 (25, 26).

In agreement with that notion, treatment of apoE-deficient mice with the AT1-specific antagonist losartan reduced the aortic protein levels of CCL25 by 89 ± 6% similarly as did the ACE inhibitor captopril (n = 3 mice/group, *, p < 0.0004; Fig. 5F). Together these data suggest a causal relationship between enhanced AT1 receptor activation and plaque-infiltrating CCL25-positive cells.

Inhibition of ACE-dependent Angiotensin II AT1 Receptor Activation Reduces CCR9 Protein Levels of Circulating Mononuclear Cells

We next analyzed the relationship between the AT1 receptor and the CCL25-specific receptor, CCR9. The CCR9 protein is expressed on plaque-infiltrating cells and on circulating mononuclear cells of apoE-deficient mice (cf. Fig. 4). Treatment with the ACE inhibitor captopril strongly decreased mononuclear cell CCR9 protein levels of apoE-deficient mice by 84 ± 6% (n = 4 mice/group, *, p < 0.001; Fig. 6A). In addition, treatment of apoE-deficient mice for 7 months with the angiotensin II AT1 receptor-specific antagonist, losartan, similarly reduced the CCR9 protein by 81 ± 6% (n = 4 mice/group; *, p < 0.001; Fig. 6A). Together these observations indicate that atherosclerosis development of apoE-deficient mice is accompanied by an AT1 receptor-dependent up-regulation of the CCR9 protein on circulating mononuclear cells.

AT1 Receptor Activation Increases CCR9 Protein Levels of Cultivated Monocytes

The causal relationship between increased CCR9 protein levels and AT1 receptor activation was analyzed with cultivated monocytes isolated from apoE-deficient mice. Incubation of cultivated monocytes for 48 h with the AT1 receptor antagonist, losartan, significantly reduced the angiotensin II-stimulated increase in CCR9 protein levels by 61 ± 7% (n = 3, *, p < 0.01) as determined by immunoblotting (Fig. 6B). As a control, losartan had no significant effect on cultivated monocytes in the absence of angiotensin II (Fig. 6B). Thus, AT1 receptor activation increases CCR9 protein levels of cultivated monocytes isolated from apoE-deficient mice.

Co-localization of AT1 and CCR9 on Plaque-resident Cells

In addition to circulating monocytes, CCR9 is present on plaque-resident macrophages (cf. Fig. 4, A and B). Immunofluorescence co-localization studies with CCR9-specific and AT1-specific antibodies, respectively, revealed localization of AT1 on CCR9-positive plaque-resident cells of apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 6C). Together these findings strongly suggest the involvement of enhanced AT1-stimulated signaling in the increased CCR9 protein levels of circulating monocytes and plaque-resident macrophages/foam cells of apoE-deficient mice.

Inhibition of CCR9 in Hematopoietic Progenitors Retards Atherosclerosis Development of ApoE-deficient Mice

To analyze whether recruitment of CCR9-positive immune cells into the aorta of apoE-deficient mice was involved in atherosclerosis development, we down-regulated the expression of Ccr9 in vivo by bone marrow transplantation of syngeneic (apoE-deficient) hematopoietic progenitors transduced with a lentivirus targeting Ccr9 by RNAi. The CCR9-RNAi lentivirus specifically reduced the protein expression of CCR9 without significantly affecting other related receptors, e.g. CCR6 and CCR7, as assessed with lentivirus-transduced receptor-expressing NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 7A). Four months after bone marrow transplantation, apoE-deficient mice with lentivirus-mediated RNAi inhibition of Ccr9 showed a significant reduction of circulating mononuclear cell CCR9 protein levels relative to control apoE-deficient mice receiving bone marrow transduced with a control lentivirus (Fig. 7B). RNAi-mediated inhibition of CCR9 induced a decrease of CCR9 protein levels on circulating mononuclear cells by 89 ± 6% (n = 5 mice/group, *, p < 0.001) as determined by densitometric immunoblot scanning (Fig. 7B).

The RNAi-mediated down-regulation of CCR9 in apoE-deficient mice was comparable with the captopril-induced inhibition of CCR9 protein levels (Fig. 7C). The induction of the CCR9 protein on circulating mononuclear cells was related to atherosclerosis development, because mononuclear cells of non-transgenic C57BL/6J control mice did not show significant CCR9 protein levels (Fig. 7C).

Immunofluorescence studies showed that plaque-resident cells were positive for CCR9 and the T cell- and monocyte/macrophage-specific immune cell markers, CD8a and MOMA-2 (cf. Fig. 4). Lentiviral-mediated RNAi inhibition of CCR9 in hematopoietic progenitors and circulating immune cells (cf. Fig. 7B) was accompanied by a significant reduction of aortic CCR9 protein levels of apoE-deficient mice by 67 ± 8% (n = 5, *, p < 0.001; Fig. 7D). As a control, treatment with captopril and losartan led to a comparable decrease of the aortic CCR9 protein of apoE-deficient mice (Fig. 7D).

Next we assessed atherosclerosis progression upon inhibition of CCR9 expression. Quantification of the atherosclerotic lesion area of the aorta revealed that inhibition of CCR9 by RNAi significantly reduced the development of the atherosclerotic lesion area by 55 ± 13% (n = 5 mice/group, *, p < 0.001; Fig. 7, E and F). As a control, down-regulation of CCR9 did not significantly affect plasma cholesterol, body weight, or blood pressure (Fig. 7G). Together these findings strongly indicate that the CCR9-CCL25 axis contributes to the development of atherosclerosis of apoE-deficient mice.

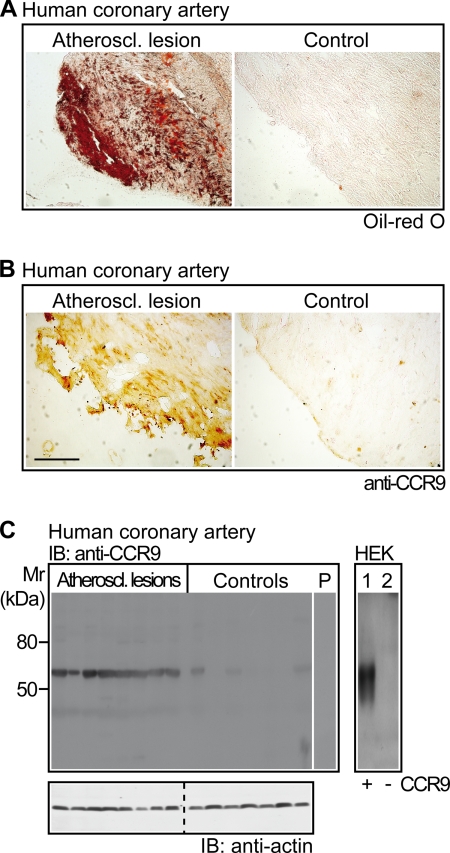

Infiltrates of CCR9-positive Cells in Atherosclerotic Lesions of Patients with Coronary Artery Disease

To analyze the potential impact of CCR9 for atherosclerosis development in patients, we determined the CCR9 protein in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary artery atherosclerosis undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Coronary artery biopsy specimens with atherosclerotic lesions as determined by positive Oil-red O staining showed a strong infiltration of CCR9-positive cells (Fig. 8, A and B, left panels). For comparison, coronary artery biopsy specimens without atherosclerotic lesions as verified by the absence of Oil-red O-positive lesions, did not show significant CCR9 staining (Fig. 8, A and B, right panels).

FIGURE 8.

Infiltrates of CCR9-positive cells in atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary artery disease. A, atherosclerotic lesions of human coronary artery biopsy specimens from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery were identified by positive Oil-red O staining of cryosections (left versus right panel). B, coronary artery biopsy specimens with atherosclerotic lesions showed strong infiltration of CCR9-positive cells (left panel), whereas CCR9 was almost undetectable on vessel specimens without Oil-red O-positive lesions (right panel). A and B, immunohistology data are representative of 6 different patients each (bar, 100 μm). C, the left panel shows immunoblot (IB) detection of CCR9 (IB: anti-CCR9) on membranes of coronary artery biopsy specimens with atherosclerotic lesions (Atheroscl. lesions; n = 8) relative to control specimens without atherosclerotic lesions (Controls; n = 7) obtained from patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. As a control, pre-absorption of the antibodies by the immunizing antigen abolished the specific staining (lane P). The lower panel shows a control immunoblot detecting β-actin (IB: anti-actin). The right panel represents an immunoblot detection of CCR9 with affinity-purified CCR9-specific antibodies pre-absorbed to human proteins on membranes of human embryonic kidney cells (HEK) overexpressing CCR9 (lane 1, +) compared with mock-transfected cells (lane 2, −).

Immunoblot detection with CCR9-specific antibodies confirmed the CCR9 protein on atherosclerotic lesions of patients (Fig. 8C). For comparison, vessel biopsy specimens without atherosclerotic lesions did not show significant CCR9 protein levels (Fig. 8C). As a control, the CCR9 antibodies cross-reacted specifically with the human CCR9 protein of transfected HEK cells, whereas the antibodies did not interact with mock-transfected control cells (Fig. 8C, lane 1 versus 2). Altogether, atherosclerotic lesions of patients and mice showed a strong infiltration with CCR9-positive cells.

DISCUSSION

Inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis because atherosclerotic plaque development involves the migration of pro-inflammatory immune cells into the arterial wall. Several studies with animal models of atherosclerosis showed that C-C chemokine receptors are important for the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic plaque formation by recruiting monocytes/macrophages into the subendothelial layer (27). Evidence for the causal involvement of individual C-C chemokines and their receptors is provided by gene inactivation and overexpression studies in mice (28–30). In addition to the experimental data, clinical studies with patients confirmed the up-regulation of several C-C chemokines in patients with atherosclerosis, unstable angina pectoris, and myocardial infarction (31, 32). The important role of C-C chemokines in atherogenesis was further confirmed by broad spectrum C-C chemokine blockers, which inhibited atherosclerotic plaque formation in mice (33, 34). The latter studies point to the therapeutic potential of C-C chemokine receptor blockade for atherosclerosis.

The present study investigated the impact of pro-inflammatory immune cells for atherosclerosis development by microarray gene expression analysis of aortic genes from atherosclerotic apoE-deficient mice relative to ACE inhibitor-treated mice. Microarray analysis and immunohistology revealed substantial effects of ACE inhibitor therapy on immune cell recruitment into the aorta. The study identified the strong up-regulation of a C-C chemokine receptor axis in atherosclerotic lesions, i.e. atherosclerosis development was accompanied by a strong increase of plaque-resident immune cells, which were positive for the chemoattractant CCL25, and its receptor CCR9. Atherosclerosis treatment by captopril reduced the aortic infiltration with CCR9- and CCL25-positive immune cells. That observation is intriguing because there seems to be a causal relationship between atherosclerosis-induced angiotensin II-AT1 receptor activation and enhanced Ccr9-Ccl25 expression. The expression of Ccl25 as an Egr-1 target gene (25), could be directly triggered by angiotensin II-mediated AT1 receptor signaling, which induces Egr-1 activation (26). In agreement with that notion, the AT1 receptor protein was co-localized with CCL25 on plaque-resident cells of apoE-deficient mice. Moreover, treatment with the AT1-specific antagonist, losartan, reduced the number of plaque-resident CCL25-positive cells in vivo.

Analogously to Ccl25, the up-regulation of Ccr9 in the course of atherosclerosis could be also mediated by angiotensin II-dependent AT1 receptor activation because ACE inhibition and AT1 antagonism blunted the increased mononuclear cell CCR9 protein levels of apoE-deficient mice, and the aortic recruitment of CCR9-positive immune cells. Moreover, angiotensin II-dependent AT1 receptor activation directly stimulated an increase in CCR9 protein levels of isolated monocytes. Moreover, the AT1 receptor protein was expressed on CCR9-positive cells of atherosclerotic plaques. A causal relationship between Ccr9 expression and AT1 receptor activation is also suggested by previous data, and could involve the AT1-dependent induction of tumor necrosis factor α synthesis (35, 36).

In addition to the relationship between the angiotensin II system and CCR9-CCL25 protein expression, several lines of evidence support the concept of a causal involvement of the CCR9-CCL25 axis in atherosclerosis development. (i) Immunohistology and immunofluorescence data revealed circulating CCR9-positive monocytes and plaque-resident CCR9-positive macrophages with characteristics of multinucleated, plaque-forming foam cells in apoE-deficient mice. (ii) CCR9-positive monocytes/macrophages are attracted by CCL25, which was released into the plaque-forming aortic intima from aorta-resident cells. (iii) Inhibition of CCR9 by RNA interference significantly attenuated the formation of atherosclerotic plaques of apoE-deficient mice. (iv) Atherosclerotic lesions of patients with coronary artery atherosclerosis showed a strong infiltration of CCR9-positive cells. Thus, the study identified the pro-atherogenic role of the C-C chemoattractant receptor, CCR9, and its specific ligand, CCL25.

In agreement with an atherosclerosis-enhancing function, the CCR9-CCL25 axis is induced by several pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic stimuli such as interferon-γ, macrophage-colony stimulating factor, and tumor necrosis factor-α (37–39). Those CCR9/CCL25-inducing factors are causally involved in atherosclerosis development (40, 41). Therefore targeting the CCL25-CCR9 axis may have potential significance in diagnosing and treating atherosclerotic plaque formation independently of the angiotensin II system.

Acknowledgment

We thank A. Abd-elbaset for excellent assistance in animal experiments.

This work was supported in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation.

- ACE

- angiotensin-converting enzyme

- CCR9

- C-C chemokine receptor type 9

- CCL25

- C-C motif chemokine 25

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- Egr-1

- early growth response protein 1

- apoE

- apolipoprotein E

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lonn E., Yusuf S., Dzavik V., Doris C., Yi Q., Smith S., Moore-Cox A., Bosch J., Riley W., Teo K.SECURE Investigators (2001) Circulation 103, 919–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen M. H., Wachtell K., Neland K., Bella J. N., Rokkedal J., Dige-Petersen H., Ibsen H. (2005) Blood Press 14, 177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J., Bosch J., Davies R., Dagenais G. (2000) New. Engl. J. Med. 342, 145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stumpe K. O., Agabiti-Rosei E., Zielinski T., Schremmer D., Scholze J., Laeis P., Schwandt P., Ludwig M.MORE study investigators (2007) Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 1, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wassmann S., Czech T., van Eickels M., Fleming I., Böhm M., Nickenig G. (2004) Circulation 110, 3062–3067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daugherty A., Rateri D. L., Lu H., Inagami T., Cassis L. A. (2004) Circulation 110, 3849–3857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayek T., Attias J., Smith J., Breslow J. L., Keidar S. (1998) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 31, 540–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keidar S., Attias J., Smith J., Breslow J. L., Hayek T. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 236, 622–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda D., Sata M. (2008) Pharmacol. Ther. 118, 268–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AbdAlla S., Lother H., Langer A., el Faramawy Y., Quitterer U. (2004) Cell 119, 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eto H., Miyata M., Shirasawa T., Akasaki Y., Hamada N., Nagaki A., Orihara K., Biro S., Tei C. (2008) Hypertens. Res. 31, 1631–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guzik T. J., Hoch N. E., Brown K. A., McCann L. A., Rahman A., Dikalov S., Goronzy J., Weyand C., Harrison D. G. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 2449–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou X., Nicoletti A., Elhage R., Hansson G. K. (2000) Circulation 102, 2919–2922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gewaltig J., Kummer M., Koella C., Cathomas G., Biedermann B. C. (2008) Hum. Pathol. 39, 1756–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chobanian A. V., Haudenschild C. C., Nickerson C., Drago R. (1990) Hypertension 15, 327–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMurray J., Solomon S., Pieper K., Reed S., Rouleau J., Velazquez E., White H., Howlett J., Swedberg K., Maggioni A., Køber L., Van de Werf F., Califf R., Pfeffer M. (2006) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 47, 726–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AbdAlla S., Lother H., el Missiry A., Langer A., Sergeev P., el Faramawy Y., Quitterer U. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6554–6565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaballos A., Gutiérrez J., Varona R., Ardavín C., Márquez G. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 5671–5675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abd Alla J., Reeck K., Langer A., Streichert T., Quitterer U. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 387, 186–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vicari A. P., Figueroa D. J., Hedrick J. A., Foster J. S., Singh K. P., Menon S., Copeland N. G., Gilbert D. J., Jenkins N. A., Bacon K. B., Zlotnik A. (1997) Immunity 7, 291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenz K., Lohse M. J., Quitterer U. (2003) Nature 426, 574–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayasooriya A. P., Mathai M. L., Walker L. L., Begg D. P., Denton D. A., Cameron-Smith D., Egan G. F., McKinley M. J., Rodger P. D., Sinclair A. J., Wark J. D., Weisinger H. S., Jois M., Weisinger R. S. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 6531–6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caligiuri G., Nicoletti A., Poirier B., Hansson G. K. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 745–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurbel M. A., Philippe J. M., Nguyen C., Victorero G., Freeman T., Wooding P., Miazek A., Mattei M. G., Malissen M., Jordan B. R., Malissen B., Carrier A., Naquet P. (2000) Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 262–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu M., Zhu X., Zhang J., Liang J., Lin Y., Zhao L., Ehrengruber M. U., Chen Y. E. (2003) Gene 315, 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S., Kawamura M., Wanibuchi H., Ohta K., Hamaguchi A., Omura T., Yukimura T., Miura K., Iwao H. (1995) Circulation 92, 88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gautier E. L., Jakubzick C., Randolph G. J. (2009) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 1412–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boring L., Gosling J., Cleary M., Charo I. F. (1998) Nature 394, 894–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aiello R. J., Bourassa P. A., Lindsey S., Weng W., Natoli E., Rollins B. J., Milos P. M. (1999) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 1518–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braunersreuther V., Zernecke A., Arnaud C., Liehn E. A., Steffens S., Shagdarsuren E., Bidzhekov K., Burger F., Pelli G., Luckow B., Mach F., Weber C. (2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 373–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraaijeveld A. O., de Jager S. C., de Jager W. J., Prakken B. J., McColl S. R., Haspels I., Putter H., van Berkel T. J., Nagelkerken L., Jukema J. W., Biessen E. A. (2007) Circulation 116, 1931–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parissis J. T., Adamopoulos S., Venetsanou K. F., Mentzikof D. G., Karas S. M., Kremastinos D. T. (2002) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22, 223–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bursill C. A., Choudhury R. P., Ali Z., Greaves D. R., Channon K. M. (2004) Circulation 110, 2460–2466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Major T. C., Olszewski B., Rosebury-Smith W. S. (2009) Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 23, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schindler R., Dinarello C. A., Koch K. M. (1995) Cytokine 7, 526–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valdivia-Silva J. E., Franco-Barraza J., Silva A. L., Pont G. D., Soldevila G., Meza I., García-Zepeda E. A. (2009) Cancer Lett. 283, 176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung Y. J., Woo S. Y., Jang M. H., Miyasaka M., Ryu K. H., Park H. K., Seoh J. Y. (2008) Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 146, 227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lean J. M., Murphy C., Fuller K., Chambers T. J. (2002) J. Cell. Biochem. 87, 386–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hosoe N., Miura S., Watanabe C., Tsuzuki Y., Hokari R., Oyama T., Fujiyama Y., Nagata H., Ishii H. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G458–G466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLaren J. E., Ramji D. P. (2009) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 20, 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleemann R., Zadelaar S., Kooistra T. (2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 79, 360–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]