Abstract

Background

Over 1.8 million women in the U.S. are veterans of the armed services. They are at increased risk of occupational traumas, including military sexual trauma. We evaluated the association between major traumas and irritable bowel syndrome among women veterans accessing VA healthcare.

Methods

We administered questionnaires to assess trauma history as well as IBS, PTSD and depression symptoms to 337 women veterans seen for primary care at VA Women’s Clinic between 2006 and 2007. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between individual traumas and IBS risk after adjustment for age, ethnicity, PTSD and depression.

Results

IBS prevalence was 33.5%. The most frequently reported trauma was sexual assault (38.9%). Seventeen of eighteen traumas were associated with increased IBS risk after adjusting for age, ethnicity, PTSD and depression, with six statistically significant (range of adjusted odds ratios (OR) between 1.85 [95% CI, 1.08–3.16] and 2.6 [95% CI, 1.28–3.67]). Depression and PTSD were significantly more common in IBS cases than controls, but neither substantially explained the association between trauma and increased IBS risk.

Conclusions

Women veterans report high frequency of physical and sexual traumas. Lifetime history of a broad range of traumas is independently associated with an elevated IBS risk.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, veterans, women, PTSD, trauma, Department of Veterans Affairs, depression

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent and costly functional gastrointestinal disorder. An IBS diagnosis is based upon presence of chronic or recurrent bowel abnormalities with abdominal pain relieved by defecation and not explainable by other causes. IBS is the most frequent cause for gastroenterologist visits in the U.S.(1) responsible for 3.7 million physician visits annually(2) and direct medical costs in excess of 1.6 billion dollars.(3) Considerable indirect costs, in excess of $19 billion dollars annually(3), also result from substantially higher total healthcare utilization and costs(4–6) and reduced work productivity.(5–7) Furthermore, a markedly decreased health-related quality of life is consistently reported in patients with IBS (4–6, 8–10), with an estimated 75% of cases still symptomatic after ten years.(11)

Although IBS is known to be clinically under-recognized among both genders in the general population(12), IBS prevalence in clinical settings is 2–3 times greater in women.(13) This female preponderance has been attributed to a combination of sex-based physiological differences and gender-based psychosocial and environmental differences, including likelihood of experiencing sexual trauma.(14) Several biological factors have been associated with IBS risk including GI infection(15–17), food intolerance/allergies(18, 19), and genetic susceptibility.(20–23) Psychological disorders including depression(24–27), anxiety(24, 27–29), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)(30–33) are more common in IBS cases.

The over 1.8 million women veterans in the U.S.(34) constitute a large occupational cohort at risk of IBS. Women also comprise approximately 14% of all active duty military personnel and 20% of all new military recruits. Currently, around 11% of all active-duty service members serving in Iraq and Afghanistan (OIF/OEF) conflicts are women, with women veterans of OIF/OEF now the single largest living group of women veterans (~187,000).(34–36) Women veterans are known to have increased risk of occupational trauma including in association with deployment and combat.(37) They also have high rates of lifetime sexual traumas including rape during military service.(38–40)

We previously reported a high survey-based prevalence of IBS as well as of psychological distress, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care at a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center.(32) The primary aims of our current research were: 1) to determine survey-based prevalence of a broad range of individual traumas in a larger sample of women veterans, and 2) to evaluate the association between individual traumas and IBS risk after adjustment for PTSD and depression. An associated exploratory aim was to perform a medical record review to assess clinical recognition of IBS in women veterans who access VA healthcare.

Methods

Sample and Questionnaires

We recruited consecutive women veterans aged 18–70 years old at the time of a scheduled primary medical care appointment in the Women’s Clinic at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas. All eligible women veterans were approached about study participation by a female researcher who was not part of the clinical staff. Study participants completed a self-administered survey prior to their clinical visit and received five-dollar remuneration. Our research protocol was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

We used the validated Bowel Disorder Questionnaire (BDQ)(41, 42) to measure type, frequency and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms experienced during the previous year. We applied symptom-based diagnostic criteria adapted from gold-standard Rome II clinical guidelines to define if a woman veteran had IBS.(32)

We used the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD) to define presence of PTSD using the recommended diagnostic cutoff of ≥107, a level at which the M-PTSD demonstrated a 93% sensitivity in comparison to the gold-standard clinical diagnosis.(43) Depression was assessed using the validated Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI-II).(44) We categorized total instrument sum score using recommended cut-points of 0–13 (no-minimal depression), 14–19 (mild depression), 20–28 (moderate depression) and 29–63 (severe depression).

We determined whether a woman veteran ever experienced a broad range of major life traumas using the validated 18-item Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ)(45). Our interim analyses suggested a very high prevalence of sexual traumas among our women veteran study participants. These results in conjunction with greatly increased national media and public awareness about the scope and burden of military sexual trauma(46) led to our addition of a second trauma measure, the Trauma Questionnaire (TQ)(47), to specifically capture timing of abusive traumas (i.e., sexual assault/rape, sexual harassment, and domestic violence) in relation to military service. The TQ was given to the final 25% of our study participants.

Electronic Medical Record Review

We evaluated VA electronic medical record of all BDQ-identified IBS cases for presence of alternate explanations for their symptoms. We also evaluated medical records for all participants for presence of a clinical IBS diagnosis and/or at least 2 cardinal symptoms consistent with a possible IBS diagnosis during the one-year time period prior to survey administration. Finally, we reviewed the records of a random sample of women veterans who refused to participate to see if they differed in likelihood of having IBS diagnosis or symptoms compared to study participants.

Statistical Analyses

We compared sociodemographic characteristics and IBS risk factors between women veterans with IBS (cases) and those without IBS (controls) using the χ2 test for categorical variables and Student’s T-test for continuous variables. We evaluated how specific traumas influence IBS risk using logistic regression. We performed three sets of multivariate analyses. In the first minimal multivariate analysis, we adjusted for two well-established confounders, age and ethnicity. In the second intermediate analysis, we also adjusted for PTSD to see if any observed association between a specific trauma and IBS risk was attributable to its presence. In the third or full multivariate model, we additionally adjusted for presence of depression. We evaluated potential effect modification by creating all first-level interaction terms and assessing their significance using the Wald test. Interaction terms were included in reported models if significant at p<0.15. All logistic regression results are reported as odds ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Trauma timing in relation to military service

We calculated lifetime prevalence of abusive traumas in the final 83 women veterans who had been given the TQ. Participants were classified as having never experienced the trauma, experienced the trauma during military service, or experienced the trauma only outside of military service. To evaluate utility of the THQ and TQ to identify forcible sexual assault or rape, we calculated concordance between their most directly comparable questions using the kappa statistic.

Validation analyses of key study measures and clinical recognition of IBS

To assess our use of the BDQ to identify cases, we first calculated the false-positive rate as the proportion of BDQ-identified IBS cases with exclusionary medical conditions or symptoms in their medical records. We also calculated negative and positive predictive values (NPV and PPV respectively) or probability that the BDQ-derived IBS case-status accurately predicts IBS case-status in the medical record. Using the validated BDQ and adapted Rome II clinical guidelines as the ‘gold standard’, we calculated clinical under-recognition of IBS as the proportion of BDQ-identified IBS cases without a confirmed, suspected or differential diagnosis of IBS in their medical record. Finally, to assess potential selection bias, we used the χ2 test to compare the proportion of participants with either a clinical IBS diagnosis or ≥ 2 symptoms suggestive of IBS reported in the medical record in both our entire cohort and in a random sample of non-participants.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Demographic and clinical features

We recruited 337 consecutive women veterans prior to their primary care visit at the Women’s Clinic at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas (11/2005–2/2006, 3/2007–6/2007). Over 95% of eligible women veterans approached about the study participated. The mean age of participants was 48.5 years, and most were African-American (48.1%) or non-Hispanic White (39.7%). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of 337 women veterans receiving primary medical care at a VA Women’s Clinic stratified according to presence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)1.

| IBS+ | IBS− | IBS+ vs. IBS− 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=113 (33.5%) |

N=224 (66.5%) |

p-value |

|

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | |||

| Age in years Mean (SD) | 46.9 (10.0) | 49.3 (12.9) | 0.06 |

| Age-group in years n (%) | 0.02* | ||

| 18–30 | 5 (4.4%) | 21 (9.4%) | |

| 31–45 | 48 (42.5%) | 61 (27.2%) | |

| 46–60 | 51 (45.1%) | 112 (50.0%) | |

| 61+ | 9 (8.0%) | 30 (13.4%) | |

| Ethnicity n (%) | 0.02*+ | ||

| African-American | 55 (48.7%) | 107 (47.8%) | |

| White | 52 (46.0%) | 82 (36.6%) | |

| Hispanic/Other | 6 (5.3%) | 34 (15.2%) | |

| Missing | - | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Education n (%) | 0.07 | ||

| High school graduate or less | 9 (8.0%) | 38 (17.0%) | |

| Some college | 70 (61.9%) | 122 (54.5%) | |

| College graduate | 33 (29.2%) | 61 (27.2%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Marital Status n (%) | 0.61 | ||

| Currently Married | 35 (31.0%) | 58 (25.9%) | |

| Previously Married | 59 (52.2%) | 122 (54.5%) | |

| Never Married | 19 (16.8%) | 43 (19.2%) | |

| Missing | - | 1 (0.4%) | |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SD, standard deviation

Statistically significant at p<0.05.

Presence or absence of IBS determined from responses to the validated Bowel Disorder Questionnaire (BDQ) consistent with a diagnosis of IBS using adapted Rome II criteria. (see also Methods section)

Missing not included in calculation of test statistic as less than 1.5% of either IBS+ cases or IBS− controls had missing values.

Although overall ethnic distributions significantly different, % African-Americans not significantly different in IBS+ and IBS− (48.7% vs. 47.8% respectively).

Approximately 33.5% (n=113) were BDQ-defined as IBS cases, with IBS prevalence among Whites modestly higher than among African-Americans (38.8% vs. 34.0% respectively, N.S.). IBS cases were slightly younger than IBS-free controls (mean age 46.9 vs. 49.3 years, P=0.06). Although the proportion of African–Americans was similar among IBS cases and controls (48.7% vs. 47.8% respectively, N.S.), cases were significantly more likely to be White (46.0% vs. 36.6%) and much less likely to be Hispanic (5.3% vs. 15.2) than controls. IBS cases were significantly more likely to have PTSD (22.1% vs. 10.7%, P=0.006) or depression (44.2% vs. 29.5%, P=0.01) than IBS-free controls. (Table 1) As (98%) of IBS cases had diarrhea as a contributing or primary clinical feature (data not shown), all subsequent multivariate analyses apply to the entire sample without adjustment for clinical features.

Trauma history as predictor of IBS

The most frequently reported traumas on the THQ were “ever being forced to have sex against your will” (46.6%) and “being fondled under force or threat” (41.8%). (Table 2) Both were more common in IBS cases than controls.

Table 2.

Prevalence of selected traumas1, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)2 and depression3 among 337 women veterans seen for primary care at a VA Women’s Clinicaccording to presence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)4.

| IBS+ | IBS− | IBS+ vs. IBS− | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=113 |

N=224 |

||

| n (%) |

p-value |

||

| Positive history of specific trauma1,5 | |||

| Someone tried to take things from you by force/threat | 44 (38.9%) | 49 (21.9%) | 0.001** |

| Someone tried and/or succeeded breaking into home while there | 21 (18.6%) | 27 (12.1%) | 0.120 |

| Serious accident anywhere | 49 (43.4%) | 81 (36.2%) | 0.245 |

| ‘Man-made’ disaster like train crash, fire, etc. where felt you/loved ones were in physical danger | 26 (23.0%) | 29 (12.9%) | 0.022* |

| Other situation where you were seriously injured | 27 (23.9%) | 34 (15.2%) | 0.054^ |

| Other situation feared might be killed/seriously injured | 52 (46.0%) | 72 (32.1%) | 0.014* |

| Seen someone seriously injured/killed | 46 (40.7%) | 72 (32.1%) | 0.148 |

| Seen or had to handle dead bodies (not funerals) | 54 (47.9%) | 82 (36.6%) | 0.058^ |

| Close family/friend killed by drunk driver | 19 (16.8%) | 38 (17.0%) | 0.943 |

| Spouse/partner/child died | 41 (36.3%) | 62 (27.7%) | 0.122 |

| Serious or life-threatening illness | 32 (28.3%) | 40 (17.9%) | 0.033* |

| Forced to have sex against will | 63 (55.8%) | 94 (42.0%) | 0.019* |

| Fondled under force or threat | 56 (49.6%) | 85 (37.9%) | 0.054^ |

| Other situation with attempted force for unwanted sexual contact | 41 (36.3%) | 47 (21.0%) | 0.003** |

| Attacked with weapon | 36 (31.9%) | 39 (17.4%) | 0.003** |

| Attacked without weapon and seriously injured | 29 (25.7%) | 34 (15.2%) | 0.023* |

| Any family member ever beaten/pushed hard enough to cause injury | 38 (33.6%) | 45 (20.1%) | 0.007** |

| Experienced any other extraordinarily stressful event | 37 (32.7%) | 51 (22.8%) | 0.057^ |

| PTSD2,5 | |||

| Present | 25 (22.1%) | 24 (10.7%) | 0.006** |

| Depression3,5 | |||

| Present | 50 (44.2%) | 66 (29.5%) | 0.010* |

Statistically significant at p<0.05.

Statistically significant at p<0.01.

Approach significance (0.05≤P≤0.06).

Presence of trauma determined by self-reported responses to the validated Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ).

Presence of PTSD determined by self-reported responses to the validated Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Trauma (M-PTSD) with score ≥107 consistent with PTSD diagnosis.

Presence of depression of at least moderate level determined by self-reported responses to the validated Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

Presence or absence of IBS as determined by self-reported responses to the validated Bowel Disorder Questionnaire (BDQ) consistent with a diagnosis of IBS per adapted Rome II criteria. (see also Methods section)

Less than 3% missing values

Collectively, nine traumas in univariate analysis were significantly associated with IBS (ORs=1.79–2.24). (Table 3) Another four traumas were associated with increased risk closely approaching significance (ORs=1.56–1.74, 0.05≤ P ≤0.06).

Table 3.

Logistic regression models evaluating lifetime history of individual traumas as potential risk factors for IBS1 among 337 women veterans receiving primary medical care at a VA Women’s Clinic.

| Type of trauma2 |

Unadjusted Estimates |

Age- and Ethnicity-Adjusted Estimates |

Age-, Ethnicity-, and PTSD3- Adjusted Estimates |

Age-, Ethnicity-, PTSD3-, and Depression4-Adjusted Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of trauma+ |

History of trauma+ |

History of trauma+ |

History of trauma+ |

|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Someone tried to take things from you by force/threat | 2.24 (95% CI 1.36–3.68)** | 2.38 (95% CI 1.42–3.98)* | 2.18 (95% CI 1.29–3.69)* | 2.16 (95% CI 1.28–3.67)* |

| Someone tried and/or succeeded breaking into home while there | 1.63 (95% CI 0.88–3.05) | 1.83 (95% CI 0.96–3.49) | 1.71 (95% CI 0.89–3.31) | 1.71 (95% CI 0.88–3.30) |

| Serious accident anywhere | 1.32 (95% CI 0.83–2.10) | 1.38 (95% CI 0.85–2.23) | 1.27 (95% CI 0.78–2.08) | 1.21 (95% CI 0.75–2.04) |

| ‘Man-made’ disaster like train crash, fire, etc. where felt that you/loved ones in physical danger | 1.97 (95% CI 1.10–3.56)* | 2.19 (95% CI 1.19–4.02)* | 2.05 (95% CI 1.10–3.80)* | 2.06 (95% CI 1.11–3.82)* |

| Other situation where you were seriously injured | 1.74 (95% CI 0.99–3.07)^ | 1.76 (95% CI 0.99–3.16)^ | 1.51 (95% CI 0.83–2.77) | 1.48 (95% CI 0.88–2.72) |

| Other situation feared might be killed/seriously injured | 1.79 (95% CI 1.12–2.87)* | 1.83 (95% CI 1.13–2.98)* | 1.55 (95% CI 0.93–2.58) | 1.52 (95% CI 0.91–2.55) |

| Seen someone seriously injured/killed | 1.42 (95% CI 0.88–2.28) | 1.40 (95% CI 0.86–2.27) | 1.27 (95% CI 0.77–2.08) | 1.25 (95% CI 0.76–2.06) |

| Seen or had to handle dead bodies (not including funerals) | 1.56 (95% CI 0.98–2.49)^ | 1.57 (95% CI 0.97–2.53)^ | 1.48 (95% CI 0.91–2.41) | 1.50 (95% CI 0.92–2.44) |

| Close family/friend killed by drunk driver | 0.98 (95% CI 0.53–1.79) | 0.99 (95% CI 0.53–1.85) | 0.92 (95% CI 0.49–1.74) | 0.93 (95% CI 0.49–1.77) |

| Spouse/partner/child died | 1.47 (95% CI 0.90–2.39) | 1.78 (95% CI 1.05–3.03)* | 1.65 (95% CI 0.96–2.83)^ | 1.65 (95% CI 0.96–2.82)^ |

| Serious or life-threatening illness | 1.79 (95% CI 1.04–3.05)* | 2.01 (95% CI 1.14–3.54)* | 2.00 (95% CI 1.12–3.55)* | 1.96 (95% CI 1.09–3.51)* |

| Forced to have sex against will | 1.74 (95% CI 1.09–2.77)* | 1.72 (95% CI 1.06–2.79)* | 1.58 (95% CI 0.97–2.60)^ | 1.55 (95% CI 0.94–2.57)^ |

| Fondled under force or threat | 1.57 (95% CI 0.99–2.50)^ | 1.48 (95% CI 0.92–2.40) | 1.29 (95% CI 0.78–2.13) | 1.26 (95% CI 0.75–2.10) |

| Other situation with attempted force for unwanted sexual contact | 2.16 (95% CI 1.30–3.57)** | 2.09 (95% CI 1.25–3.49)* | 1.87 (95% CI 1.10–3.19)* | 1.85 (95% CI 1.08–3.16)* |

| Attacked with weapon | 2.20 (95% CI 1.30–3.72)** | 2.43 (95% CI 1.40–4.19)* | 2.19 (95% CI 1.25–3.82)* | 2.15 (95% CI 1.23–3.78)* |

| Attacked without weapon and seriously injured | 1.91 (95% CI 1.09–3.34)* | 2.11 (95% CI 1.18–3.78)* | 1.84 (95% CI 1.01–3.35)* | 1.80 (95% CI 0.97–3.23)^ |

| Family member beaten/pushed you hard enough to cause injury | 2.01 (95% CI 1.20–3.35)* | 2.23 (95% CI 1.30–3.80)* | 1.95 (95% CI 1.12–3.38)* | 1.91 (95% CI 1.08–3.34)* |

| Experienced any other extraordinarily stressful event | 1.63 (95% CI 0.98–2.71)^ | 1.73 (95% CI 1.02–2.91)* | 1.65 (95% CI 0.97–2.80)^ | 1.61 (95% CI 0.95–2.75)^ |

Statistically significant at p<0.05.

Statistically significant at p<0.01.

Approach significance (0.05≤P≤0.06).

CI, confidence interval; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Presence of IBS determined according to responses to the Bowel Disorder Questionnaire (BDQ) consistent with a diagnosis of IBS per adapted Rome II criteria. (see also Methods section)

Trauma history determined by responses to the Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ)

Presence of PTSD determined by responses to the Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Trauma (M-PTSD) with score ≥107 consistent with diagnosis of PTSD.

Presence of depression of at least moderate severity determined by responses to the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) with score ≥20.

In the first minimal multivariate model which adjusted for age and ethnicity, eleven traumas (61%) were associated with significantly increased risk (ORs=1.72 – 2.43), with another four (22%) closely approaching significance. (Table 3) In the second model which also adjusted for PTSD, the excess IBS risk associated with individual traumas was slightly attenuated in comparison to the minimal model, with seven traumas (39%) still associated with significant excess risk (ORs=1.84 – 2.19). Similar to results from the first or minimal model, all but one remaining trauma, although non-significant, were associated with excess risk (ORs=1.27–1.71). (Table 3) Across all trauma histories, PTSD was consistently associated with an independent 100% increase in IBS risk (ORs =2.02–2.70, data not shown). In the final multivariate model that also adjusted for depression, IBS risk was again attenuated only slightly, significant excess risk was still observed for six traumas, with another four closely approaching significance. Further, additional adjustment for depression only minimally attenuated the independent excess IBS risk associated with PTSD for all but three traumas (home break-in, seeing/handling dead bodies not related to funerals, and serious illness), where there was evidence of strong confounding by depression. (data not shown)

Only one trauma, “having someone close to you killed by a drunk driver”, was not associated with increased IBS risk in univariate or multivariate analysis.

We found no evidence of interaction between any main effects or of lack of model fit in any multivariate model.

Military sexual trauma (MST) and overlap with other abusive traumas

The final 83 study participants completed the TQ. There was high concordance (κ=0.75, P=0.001) between comparable TQ and THQ items for occurrence of forcible sexual assault expressed as ‘Has anyone ever used force or threat of force to have sex with you against your will?’ (TQ) and ‘Has anyone ever made you have intercourse, oral or anal sex against your will?’ (THQ) Specifically, 90% of women who reported experiencing sexual assault on the TQ also reported experiencing it on the THQ.

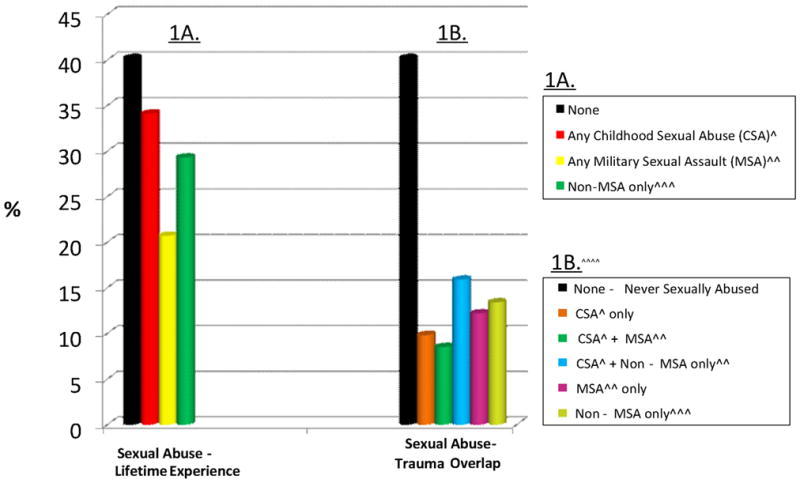

Approximately 60% of women who completed the TQ reported experiencing ≥1 sexual assault during their lifetime, with 21% reporting forcible sexual assault during military service. (Figure 1) Slightly more than one-third (34%) reported sexual abuse during childhood, with 25% subsequently reporting sexual assault or rape during military service. More women veterans reported domestic violence than sexual harassment or assault occurred during military service (49% vs. 38% vs. 21% respectively). Overall, almost two-thirds experienced ≥1 of these three abusive traumas (rape, sexual harassment and domestic violence) during military service, with 39% of abused women experiencing ≥2 traumas. (data not shown)

Fig 1.

History of Sexually Abusive Traumas reported on Trauma Questionnaire (TQ) by final 83 women veteran study participants*.

*Only 1 missing value (1%)

^Sexual abuse in childhood by age 13 and perpetrated by someone at least 5 years older.

^^TQ-defined sexual assault or sex against will by force or threat of force occuring at least once during military service.

^^^Any non-childhood sexual assault that occurred at any time other than during military service.

^^^^Given TQ question structure, can only determine if MSA or another non-MSA occured but not if both an MSA and a non-MSA occurred.

Validation of BDQ to identify IBS cases and evaluation of selection bias

Use of the BDQ to identify IBS cases was associated with a low false positive rate, as <4% had exclusionary conditions anywhere in their medical record. Use of the BDQ to identify presence of an IBS diagnosis in the medical record was associated with good NPV (0.73, [95% CI, 0.67–0.78]). However, the corresponding PPV was lower (0.65, [95% CI, 0.51–0.77]).

Overall, medical-record documented prevalence of either an IBS diagnosis or of ≥2 symptoms suggestive of IBS in the year prior to the index clinic visit were similar in study participants and in a random sample of 35 non-participants (14.3% vs. 16.8% for diagnosis and 17.1% vs. 17.1% for ≥2 symptoms, both N.S.).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study conducted in 337 women veterans receiving primary medical care at the VA is the first study to assess lifetime history of a broad range of multiple individual traumas as risk factors for symptom-confirmed IBS in any veteran or military population.

All but one of the broad range of traumas examined were associated with increased IBS risk in women veterans, most with modest to moderate 50–115% excess risk. The excess risk associated with individual traumas persisted with only minor attenuation in multivariate analyses even after adjusting for other well-established risk factors, specifically age, ethnicity, depression and PTSD. However, the number of traumas reaching or approaching significance was reduced given concomitant reduction in study power.

The very high prevalence of sexual traumas observed in this study is not completely surprising. A mandated VA-wide clinical screening for military sexual trauma demonstrated a 22% prevalence rate in women veterans.(38) To better understand how often a self-reported history of sexual assault may have in fact included forcible sexual assault during military service, the final 25% of participants completed a second trauma measure, the Trauma Questionnaire (TQ).(47) More than 40% of women reporting a history of non-childhood sexual assault on this measure reported experiencing forcible sexual assault during military service. However, the substantive reduction in sample size, particularly of IBS cases, precluded valid assessment of abusive traumas experienced specifically during military service as independent IBS risk factors.

Depression and PTSD are among the top three diagnostic codes assigned to women veterans using the VA, with both shown to increase IBS risk in women veterans.(31, 32) PTSD was associated with an independent 100% increased IBS risk for 15 of 18 traumas we assessed. However, PTSD neither substantially explained nor modified the independent increased IBS risk conveyed by individual traumas. This modest to moderate increased IBS risk persisted for most traumas even after additional adjustment for depression.

A number of studies have evaluated individual abusive traumas like sexual abuse as IBS risk factors,(48–57) with most reporting increased IBS risk.(49–54, 56, 57) One group evaluated abusive traumas as IBS risk factors in a manner generally comparable to ours, i.e., a survey-based epidemiologic study conducted in a single general adult population not selected based on disease or clinical sub-specialty and with adjustment for concomitant psychological comorbidity. Their initial study was a mail survey to residents of a Penrith, Australia(48), with subsequent interview of a small sample of initial participants.(55) In contrast to our findings, they found almost no abusive traumas were associated with excess IBS risk after adjustment for general overall psychological morbidity level and neuroticism. Some of this discrepancy between our study findings is likely attributable to substantial differences in our underlying target populations, including our restriction to women, and specifically women veterans, who have a high lifetime trauma burden, and in measures of psychological comorbidity. Other relevant factors may include our use of direct recruitment with high participation rate compared to their use of a mailed survey and follow-up interviews in a sub-sample of participants with lower participation rates. The consistency of our findings suggestive of excess IBS risk with many abusive as well as non-abusive traumas supports the internal validity of our findings. Future comparably conducted research may help clarify whether abusive as well as non-abusive traumas are independently associated with excess IBS risk after adjusting for similar psychological comorbidities in other civilian and military populations.

Most studies that have evaluated the association between military service and risk of GI symptoms or disorders including IBS examined deployment in veterans of the first Gulf War. A 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report evaluating this literature highlighted several key individual study findings including: 1) epidemiologic data demonstrating substantial deployment-related increases in IBS; 2) physiologic data demonstrating persistent low-grade colonic inflammation and increased visceral hypersentivity among deployed Gulf War veterans with IBS or IBS-type symptoms; and 3) epidemiologic data demonstrating greatly increased risk of IBS among veterans with a history of gastroenteritis, with effects particularly elevated among deployed veterans.(58) Unfortunately, we could not assess if there was a deployment-IBS association in our women veterans because we did not have access to necessary Department of Defense data to confirm deployment, including a history of combat or deployment-related gastroenteritis. However, our finding that multiple individual traumas, including many that may plausibly happen during deployment, independently increased risk of symptom-confirmed IBS in women veterans is consistent with the IOM findings. Our study offers several additions to the IOM-cited literature. First, we demonstrated that a trauma-IBS association exists for a broad range of traumas and persists even after adjustment for PTSD and depression. These two key psychological comorbidities in veterans that often co-occur with IBS were not controlled for in most of these Gulf War studies which often evaluated IBS as only one of multiple potential health outcomes. Second, because our study participants spanned a broad age-range, our results suggest a trauma-IBS association is unlikely to be limited to a single military cohort or era. Finally, our findings demonstrate a trauma-IBS association exists in women veterans, a population that was either absent or represented only a very small minority of the veterans evaluated in these earlier Gulf War studies.

Recent experimental and clinical studies have evaluated the association between early life trauma and stress in relation to IBS. In the neonatal maternal separation model (NMS) of IBS in rodents, several traumatic exposures during the early neonatal period increase visceral hyperalgesia,(59–62) a hallmark IBS symptom. For example, recent NMS studies demonstrated receipt of noxious stimuli like colorectal distention in this hyporesponsive periods leads to alterations in nociception, including increased immune and neurochemical responsivity at the level of the enteric nervous system.(61, 63) Others have shown this NMS-related visceral hyperalgesia persist in adulthood in response to subsequent noxious stimuli.(60, 62) Additional indirect evidence comes from epidemiologic studies demonstrating perinatal gastric suction(64) or living in a wartime environment during specific intervals in infancy(65) increases risk of functional gastrointestinal disorders including IBS in adulthood.

NMS in rodents also leads to chronic dysregulation in the limbic-pituatary-hypothalamic-adrenal (LPHA) axis,(66–68) with chronic LPHA dysregulation in humans associated with PTSD and depression(69), conditions often co-occurring with IBS. A recent structural MRI imaging study found increased hypothalamic gray matter and thinning of the anterior midcingulate limbic cortex in IBS cases compared to matched healthy controls.(70) Selective neural thinning that was observed only in IBS cases occurred in the supraspinal dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is extensively interconnected with both the limbic system and neocortex association areas and plays an important role in motor regulation and executive function. A recent functional MRI imaging study evaluated neural activation and pain perception in response to rectal distention in women, half of whom had IBS and half of whom had a history of abuse.(71) It demonstrated that both pain perception and a history of abuse were independently associated with increased activity in posterior and middle dorsal cingulate limbic cortex, with greatest effects observed in women who had both IBS and a history of abuse. Decreased activity in another limbic structure, the supragenual anterior cingulate cortex, was only observed in women with IBS who also had an abuse history. However, given the cross-sectional design and limited sample size of these studies, it is currently unknown to what extent these structural and functional differences may reflect increased susceptibility to versus are a result of or are reinforced by clinical presence of IBS.

Our results that a broad range of traumas are associated with increased IBS risk in women veterans are consistent with this emerging data suggesting potential biological linkage between trauma and IBS within the complex reciprocal interplay of the gut and the enteric nervous, central nervous and neuroendocrine systems. Our results also suggest the period in which traumas influence IBS risk may extend beyond early childhood into adulthood and also include a much broader range of major traumas than just abusive traumas. Additional indirect evidence supportive of potential role for trauma and stressors experienced in adulthood to increase IBS susceptibility comes from a recent experimental study in young healthy adult women that demonstrated visceral hypersensitivity and maladaptive intestinal epithelial responsitivity, both well-known to occur with IBS, were increased after receipt of noxious jejunal stimulation, with effects larger in healthy women placed under conditions of moderate compared to low background stress.(72)

Our study has multiple strengths including the prospective recruitment of a large and multiethnic sample of women veterans, restriction to a general care as opposed to specialty- or disease-specific clinical setting, high participation rate and use of validated measures. We also verified all IBS cases and controls in our study were veterans since up to half of women accessing VA healthcare are non-veterans (e.g., spouses/dependents or employees).(73) Our physician-performed medical record review substantiated our measure for the presence of IBS. It also provided data suggestive of substantial under-recognition of IBS among women veterans using the VA. Finally, to our knowledge, our study is the most comprehensive evaluation of individual traumas including multiple major lifetime traumas not previously examined for IBS in any population.

Our study also has several limitations. First, our study evaluated women veterans who have very high prevalence of IBS symptoms, trauma and psychological disorders; therefore, our findings may not generalize to women veterans who do not use the VA, to civilian women, or male veterans. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences as we cannot reliably establish whether IBS began before or after a trauma occurred. However, the consistent finding that a broad range of traumas, both abusive and non-abusive, experienced over a lifetime increased IBS risk suggests trauma is likely antecedent to IBS in at least some cases. Lastly, although recent community data suggests most IBS cases are symptomatic a decade later,(11) we were unable to evaluate differences in trauma-IBS association between those with long-standing versus only recent IBS.

Our study demonstrated lifetime history of a broad range of major life traumas beyond those experienced in early childhood or that are abusive in nature are associated with increased IBS risk in women veterans, even after adjusting for their most common psychological comorbidities, depression and PTSD. Our findings also have potentially important implications for healthcare delivery for women veterans. Specifically, they suggest women veterans who use the VA and who screen positive for PTSD, depression or military sexual trauma during system-mandated universal screenings for these conditions may also benefit from additional screening for IBS. Finally, our results suggestive of considerable underdiagnosis of IBS in women veterans, also suggest that obtaining a detailed trauma history may be useful in facilitating appropriate clinical recognition and diagnosis of IBS.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported in part by the Houston VA HSR&D Center of Excellence (HFP90-020) and a project grant from Novartis pharmaceuticals (PI: H.B. El-Serag, MD, MPH). Dr. White receives salary support from a Career Development Award (NIDDK K-01, DK081736-01), Dr. Savas from a National Research Service Award (5 T32 HP10031-09) and the Health Cancer Education and Career Development Program (NCI/NIH R25-CA-57712), and Dr. El-Serag from an Advanced Career Development Award (NIDDK K-24, DK078154-03).

Role of the Funding Source: The study was funded in part by the Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The sponsors had no role in study design, implementation, analysis, interpretation or decision to publish.

Abbreviations

- BDI-II

Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition

- BDQ

Bowel Disorder Questionnaire

- CI

confidence interval

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- M-PTSD

Mississippi Scale Combat-Related PTSD

- MST

military sexual trauma

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- THQ

Trauma History Questionnaire

- TQ

Trauma Questionnaire

- VA

Department of Veteran Affairs

Footnotes

Authors’ Involvement: Donna White: Conception, analysis, writing, approval of final manuscript

Lara Savas: Conception, approval of final manuscript

Kuang Daci: Conception, approval of final manuscript

Rola Elsearg: Conception, approval of final manuscript

David P. Graham: Conception, approval of final manuscript

Stephanie Fitzgerald: Conception, approval of final manuscript

Shirley Laday Smith: Conception, approval of final manuscript

Gabriel Tan: Conception, approval of final manuscript

Hashem El-Serag: Conception, writing, approval of final manuscript

Reference List

- 1.Russo MW, Gaynes BN, Drossman DA. A national survey of practice patterns of gastroenterologists with comparison to the past two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29(4):339–43. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(5):1500–11. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, et al. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(6):2108–31. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RL, Von KM, Whitehead WE, et al. Costs of care for irritable bowel syndrome patients in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(11):3122–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pare P, Gray J, Lam S, et al. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther. 2006;28(10):1726–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60(1):77–81. doi: 10.1159/000007593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, et al. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(1 Suppl):S17–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(6):541–50. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318189a7f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne AM, et al. Racial differences in the impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(9):782–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000140190.65405.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JM, Choi MG, Kim YS, et al. Quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome in Korea. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(4):435–46. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, et al. Fluctuation of gastrointestinal symptoms in the community: a 10-year longitudinal follow-up study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(8):1013–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(11):1365–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih YC, Barghout VE, Sandler RS, et al. Resource utilization associated with irritable bowel syndrome in the United States 1987–1997. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(8):1705–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1016471923384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne S. Sex, gender, and irritable bowel syndrome: making the connections. Gend Med. 2004;1(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(04)80007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuteja AK, Talley NJ, Gelman SS, et al. Development of functional diarrhea, constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and dyspepsia during and after traveling outside the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(1):271–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes DY, Wallace M. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8(4):327–32. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji S, Park H, Lee D, et al. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Shigella infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(3):381–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, et al. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(7):765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uz E, Turkay C, Aytac S, et al. Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome in Turkish population: role of food allergy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(4):380–3. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225589.70706.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pata C, Erdal E, Yazc K, et al. Association of the −1438 G/A and 102 T/C polymorphism of the 5-Ht2A receptor gene with irritable bowel syndrome 5-Ht2A gene polymorphism in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(7):561–6. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JM, Choi MG, Park JA, et al. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18(11):995–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito YA, Locke GR, III, Zimmerman JM, et al. A genetic association study of 5-HTT LPR and GNbeta3 C825T polymorphisms with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(6):465–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Veek P, van den Berg M, de Kroon YE, et al. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(11):2510–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gros DF, Antony MM, McCabe RE, et al. Frequency and severity of the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome across the anxiety disorders and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(2):290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillila MT, Hamalainen J, Heikkinen ME, et al. Gastrointestinal complaints among subjects with depressive symptoms in the general population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(5):648–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wojczynski MK, North KE, Pedersen NL, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: a co-twin control analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2220–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu WH, Wong WM, Lam CL, et al. Anxiety but not depression determines health care-seeking behaviour in Chinese patients with dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(12):2081–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholl BI, Halder SL, Macfarlane GJ, et al. Psychosocial risk markers for new onset irritable bowel syndrome--results of a large prospective population-based study. Pain. 2008;137(1):147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S, Wu J, Ma YL, et al. Research article: Irritable bowel syndrome is strongly associated with generalized anxiety disorder: a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seng JS, Clark MK, McCarthy AM, et al. PTSD and physical comorbidity among women receiving Medicaid: results from service-use data. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(1):45–56. doi: 10.1002/jts.20097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobie DJ, Kivlahan DR, Maynard C, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in female veterans: association with self-reported health problems and functional impairment. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(4):394–400. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savas LS, White DL, Wieman M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia among women veterans: prevalence and association with psychological distress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liebschutz J, Saitz R, Brower V, et al. PTSD in urban primary care: high prevalence and low physician recognition. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):719–26. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Office of the Actuary. VetPop. 2007 9-30-2006. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Women Veterans Health Care: The Changing Face of Women Veterans. Apr 22, 2009. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Office of Policy and Planning. Women Veterans: Past, Present and Future, 2007 Update. 2007 Sep 30; Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zinzow HM, Grubaugh AL, Monnier J, et al. Trauma among female veterans: a critical review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(4):384–400. doi: 10.1177/1524838007307295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Military Sexual Trauma Support Team. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health Services, MST Support Team. 2007. Military Sexual Trauma Screening Report: Fiscal Year 2006. Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldzweig CL, Balekian TM, Rolon C, et al. The state of women veterans’ health research. Results of a systematic literature review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 (Suppl 3):S82–S92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Street AE, Stafford J, Mahan CM, et al. Sexual harassment and assault experienced by reservists during military service: prevalence and health correlates. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45(3):409–19. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.06.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, III, et al. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(8):671–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, et al. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65(11):1456–79. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL. Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: three studies in reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(1):85–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck A, Steer R, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: Psychology Corporation; 1996. (BDI-II) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green B. Trauma History Questionnaire, in Stamm BH, Varra EM (eds): Measurement of Stress, Trauma and Adaptation. In: Stamm B, Varra E, editors. Measurement of Stress, Trauma and Adaptation. Lutherville, MD: Sidran; 1966. pp. 366–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Washington D. From Victim To Accused Army Deserter. The Washington Post. 2006 September 19; [Google Scholar]

- 47.McIntyre LM, Butterfield MI, Nanda K, et al. Validation of a Trauma Questionnaire in veteran women. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(3):186–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut. 1998;42(1):47–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1040–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR. Self-reported abuse and gastrointestinal disease in outpatients: association with irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(3):366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reilly J, Baker GA, Rhodes J, et al. The association of sexual and physical abuse with somatization: characteristics of patients presenting with irritable bowel syndrome and non-epileptic attack disorder. Psychol Med. 1999;29(2):399–406. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Histories of sexual victimization in patients with irritable bowel syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(10):1502–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delvaux M, Denis P, Allemand H. Sexual abuse is more frequently reported by IBS patients than by patients with organic digestive diseases or controls. Results of a multicentre inquiry. French Club of Digestive Motility. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9(4):345–52. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jamieson DJ, Steege JF. The association of sexual abuse with pelvic pain complaints in a primary care population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(6):1408–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. A history of abuse in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: the role of other psychosocial variables. Digestion. 2005;72(2–3):86–96. doi: 10.1159/000087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drossman DA, Li Z, Leserman J, et al. Health status by gastrointestinal diagnosis and abuse history. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(4):999–1007. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(11):828–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Institute of Medicine. Committee on Gulf War and Health: Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. Gulf War and Health: Volume 8: Update of Health Effects of Serving in the Gulf War. 2010 Ref Type: Report. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chung EK, Zhang X, Li Z, et al. Neonatal maternal separation enhances central sensitivity to noxious colorectal distention in rat. Brain Res. 2007;1153:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lopes LV, Marvin-Guy LF, Fuerholz A, et al. Maternal deprivation affects the neuromuscular protein profile of the rat colon in response to an acute stressor later in life. J Proteomics. 2008;71(1):80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ren TH, Wu J, Yew D, et al. Effects of neonatal maternal separation on neurochemical and sensory response to colonic distension in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292(3):G849–G856. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00400.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tyler K, Moriceau S, Sullivan RM, et al. Long-term colonic hypersensitivity in adult rats induced by neonatal unpredictable vs predictable shock. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(9):761–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barreau F, Salvador-Cartier C, Houdeau E, et al. Long-term alterations of colonic nerve-mast cell interactions induced by neonatal maternal deprivation in rats. Gut. 2008;57(5):582–90. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.126680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anand KJ, Runeson B, Jacobson B. Gastric suction at birth associated with long-term risk for functional intestinal disorders in later life. J Pediatr. 2004;144(4):449–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klooker TK, Braak B, Painter RC, et al. Exposure to Severe Wartime Conditions in Early Life Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levine S. Primary social relationships influence the development of the hypothalamic--pituitary--adrenal axis in the rat. Physiol Behav. 2001;73(3):255–60. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Renard GM, Rivarola MA, Suarez MM. Sexual dimorphism in rats: effects of early maternal separation and variable chronic stress on pituitary-adrenal axis and behavior. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25(6):373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oomen CA, Girardi CE, Cahyadi R, et al. Opposite effects of early maternal deprivation on neurogenesis in male versus female rats. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e3675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reagan LP, Grillo CA, Piroli GG. The As and Ds of stress: metabolic, morphological and behavioral consequences. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;585(1):64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blankstein U, Chen J, Diamant NE, et al. Altered brain structure in irritable bowel syndrome: potential contributions of pre-existing and disease-driven factors. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(5):1783–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ringel Y, Drossman DA, Leserman JL, et al. Effect of abuse history on pain reports and brain responses to aversive visceral stimulation: an FMRI study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):396–404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alonso C, Guilarte M, Vicario M, et al. Maladaptive intestinal epithelial responses to life stress may predispose healthy women to gut mucosal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):163–72. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frayne SM, Yano EM, Nguyen VQ, et al. Gender disparities in Veterans Health Administration care: importance of accounting for veteran status. Med Care. 2008;46(5):549–53. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181608115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]