Abstract

The Hsp60-type chaperonin GroEL assists in the folding of the enzyme human carbonic anhydrase II (HCA II) and protects it from aggregation. This study was aimed to monitor conformational rearrangement of the substrate protein during the initial GroEL capture (in the absence of ATP) of the thermally unfolded HCA II molten-globule. Single- and double-cysteine mutants were specifically spin-labeled at a topological breakpoint in the β-sheet rich core of HCA II, where the dominating antiparallel β-sheet is broken and β-strands 6 and 7 are parallel. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was used to monitor the GroEL-induced structural changes in this region of HCA II during thermal denaturation. Both qualitative analysis of the EPR spectra and refined inter-residue distance calculations based on magnetic dipolar interaction show that the spin-labeled positions F147C and K213C are in proximity in the native state of HCA II at 20 °C (as close as ∼8 Å), and that this local structure is virtually intact in the thermally induced molten-globule state that binds to GroEL. In the absence of GroEL, the molten globule of HCA II irreversibly aggregates. In contrast, a substantial increase in spin–spin distance (up to >20 Å) was observed within minutes, upon interaction with GroEL (at 50 and 60 °C), which demonstrates a GroEL-induced conformational change in HCA II. The GroEL binding-induced disentanglement of the substrate protein core at the topological break-point is likely a key event for rearrangement of this potent aggregation initiation site, and hence, this conformational change averts HCA II misfolding.

Keywords: Molecular chaperone, Protein aggregation, Unfoldase, Carbonic anhydrase, Molten globule, Misfolding

Introduction

Protein folding is facilitated in vivo because aberrant folding is involved in a large number of devastating diseases such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer's disease, and familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy [1]. It is known that misfolded protein intermediates tend to aggregate into oligomers [2, 3]. Therefore, recognition of aggregation-prone intermediates is essential for the viability of the cell, and hence, protein folding in vivo demands strict quality control. Here, molecular chaperones constitute the cellular first line of defense both for correct folding and trafficking [4].

The Hsp60 class of molecular chaperones forms oligomeric assemblies of 14 or 16 subunits stacked in a double ring arrangement called chaperonin. Chaperonins are specialized in binding to partially unfolded intermediates, often of molten-globule type possessing significant structure. Such intermediates are notorious for their specific aggregation prone behavior [5, 6]. One important role of a molecular chaperone is to provide a container that prevents intermolecular interactions and keeps the substrate protein secluded from bulk proteins. For cylindrical chaperonin-type chaperones, this is referred to as the “Anfinsen's cage” [7]. The importance of this role is evident because Hsp60 levels are increased under stressful conditions such as elevated temperature, where aggregation is promoted. However, this is not the complete story. If chaperonins were merely functioning as holdases, the Hsp60 system would be overwhelmed with trapped substrates. A more active role has therefore been suggested where an unfoldase function would actively unfold a potentially misfolded substrate, giving it a new chance to fold correctly [8]. There is still a debate in the literature regarding the role of GroEL as a passive test tube or an active unfoldase [9]. We have previously shown that GroEL, in the absence of ATP and GroES, has an active role in unfolding the substrate through binding-induced unfolding force [10–12]. A very similar binding-induced domain separation of β-actin by the interaction of the chaperonin TriC was recently demonstrated by us [13]. In comparison with GroEL, the TriC binding-induced domain separation was more specific and dramatic, but also for GroEL-bound β-actin, conformational rearrangements were evident [14]. Unfoldase activity has also been suggested for the Hsp70 system DnaK, once considered to be a classic example of a holdase [15]. Other chaperone systems are known for their strong unfoldase activity, for example, the Hsp100 system ClpA stretches its substrates apart to facilitate degradation [16].

It is important to clarify what is meant by unfoldase activity. An active unfolding mechanism does not require complete unfolding of the substrate protein. Instead, a “loosening up” of the substrate protein structure through partial unfolding would be evidence for unfoldase activity.

It has been shown that GroEL alone can actively assist in the folding of certain proteins [8, 10, 12, 17–19]. The first step in GroEL interaction is the binding of the peripheral part of the substrate protein, in our case, human carbonic anhydrase II (HCA II), which has a molecular mass of 29.3 kDa. We have studied the complex between the molten-globule state of HCA II [20] and GroEL [10]. GroEL protects HCA II in this aggregation-prone intermediate state from aggregation at elevated temperatures [21]. As a consequence of binding, the GroEL molecule expands to accommodate the substrate and utilizes this expansion to stretch HCA II [11, 12].

In general, the structure of the bound substrate is of particular interest and all performed studies report an unstructured protein. In the case of barnase, an H/D exchange is shown corresponding to an unfolded state [18]. The substrates dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH), which are of similar size as HCA II, shows partially intact cores with native like topology, however, with very labile NHs with modest protection factors only in the 100 range [22, 23]. The preserved native-like topology has been the main argument against binding-induced unfoldase activity of GroEL-bound substrates [22, 23]; however it has been shown by the Shortle group that a protein can preserve native-like topology even under highly denaturing conditions such as 8 M urea [24].

Surprisingly few data are available on the structure of a captured GroEL substrate. NMR measurements have been limited to H/D exchange measurements. In addition, partial protease digestion and hydrogen/tritium exchange have been performed [25, 26], as well as cryo electron microscopy [27]. We have used site-specific spin [10] and fluorescence labeling [12] to investigate the structure of HCA II in the GroEL-bound state. Those studies were very informative but were limited to single positions throughout the structure. Measuring the substrate protein expansion that would follow from GroEL stretching requires intramolecular distance measurements under near physiological temperatures in solution. Our previous work along these lines has relied on FRET measurements from multiple Trp-donors to single site-specific AEDANS-acceptors inserted in the protein. There are some limitations to FRET in measuring small changes in protein compactness, since FRET is most suitable for measurements of distances in the range 10–100 Å [28]. To obtain information in the 5–20 Å range, we have chosen to use an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) approach based on the magnetic dipolar interaction of a doubly spin-labeled protein, a technique that is most commonly used on frozen samples at high protein concentrations [29–31]. The site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) technique has very recently been applied on site-directed mutagenesis of unnatural amino acids rendering a very interesting approach for protein structure and dynamics studies, which even goes beyond the conventional cysteine labeling approach [32]. The lineshape of the EPR spectrum for the singly spin-labeled protein sample depends on the mobility of the spin label, which relates to the protein structure in the vicinity of the spin label. Previously, the GroEL-HCA II interaction was studied with the SDSL approach, and it was found that the interaction leads to higher flexibility of the rigid and compact hydrophobic core of HCA II, which is likely to facilitate rearrangement of misfolded structure [10]. In this work, we have gone further, by introducing not only single spin labels but also a pair of spin labels at sites located at a topological breakpoint in the central core of HCA II on cysteine mutants. Using this approach, it should be possible to monitor the change in intramolecular distance resulting from GroEL-HCA II interaction in the required temperature range of 20–60 °C. The modified sites are F147 of β-strand 6 and K213 of β-strand 7 (Fig. 1). This core forms a stable residual structure in the unfolded protein and is a nucleation site for specific interactions in the aggregation of the molten-globule intermediate [3, 12, 33, 34]. Our specific question we addressed in this study was: To what extent does the GroEL-induced stretching of bound HCA II separate the central β-strands in comparison to the previously reported overall expansion of GroEL bound HCA II?

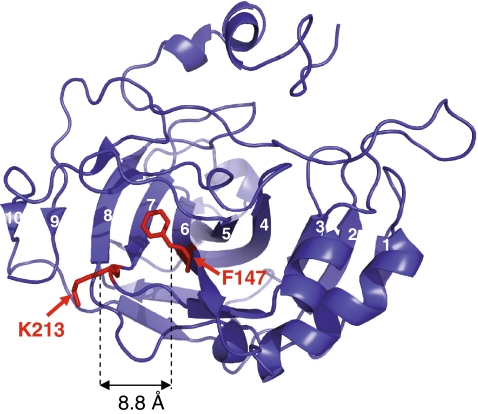

Fig. 1.

The HCA II structure in cartoon representation with the sites of mutation, residues F147 and K213, indicated in red. The β-carbon–β-carbon distance between these sites is 8.8 Å. The ten central β-strands of HCA II are numbered. β-strands 6 and 7 are parallel and the remainder of the central β-sheet is in an antiparallel arrangement. The figure was generated using PyMol (DeLano Scientific, LLC) with coordinates provided from RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession code 2CBA [39])

Materials and methods

Chemicals The spin label (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl)-methanethiosulfonate (MTSSL) was purchased from Reanal (Budapest, Hungary). Sucrose was of reagent grade and was obtained from Aldrich (Stockholm, Sweden).

Production, purification, and spin labeling of protein mutants GroEL was produced using temperature induction (42 °C for 4 h) of RSC 677 cells transformed with the pBS559 plasmid and was purified as previously described [21]. Three mutants of HCA II were made using the cysteine-free C206S template (possessing the same properties as the wild-type HCA II): F147C, K213C, and F147C/K213C. Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA). All mutants were verified by DNA sequencing. Spin labeling of the mutants with MTSSL was performed in the denatured state followed by a refolding step as previously described [34, 35], producing the side chain commonly designated R1. The purity of all proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

Stability measurements To determine the temperature stability of the HCA II mutants, in the absence and presence of GroEL, unfolding in buffer was monitored by intrinsic Trp fluorescence [10] or by enzyme activity (CO2-hydration) [21] for sucrose solutions. Fluorescence spectra of 0.85 μM protein in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5, were obtained on a Hitachi F-4500 spectrofluorimeter equipped with a thermostated cell. Spectra were recorded using a 1-cm quartz cuvette in a stepwise manner over a temperature range of 5–65 °C. The excitation wavelength was 295 nm and three accumulative emission spectra were recorded in the wavelength region 310–450 nm. Five-nanometer slits were used for both excitation and emission.

EPR measurements X-band EPR measurements were performed using a Bruker ER200D-SRC CW EPR spectrometer and an ER4102TM cavity with its standard variable temperature quartz insert for flat cells. Samples were introduced in an appropriate quartz flat cell (Wilmad, Buena, NJ, USA). A Bruker VT4112 system was used to provide a flow of nitrogen gas with constant temperature at the position of the sample. Before each measurement, the temperature inside the quartz insert, at the center of the resonator, was controlled with an external thermocouple. HCA II mutant concentrations were 6.8 μM, and when GroEL was added, the GroEL:HCA II molar ratio was 1.0.A first set of samples of MTSSL-labeled F147C (F147R1), K213C (K213R1), and F147C/K213C (F147R1/K213R1), without/with GroEL present was prepared in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5, at a sample volume of 200 μL. Measurements were performed at 20 and 50 °C using a scan width of 120 G and a measurement time of 30–60 min. For measurements at 50 °C, we rapidly inserted the sample flat cell in the preheated resonator. Two different procedures were then adopted: (1) A series of single 2.8-min scans were recorded immediately after having inserted the sample and tuned the resonator. This was done to follow the slow kinetics of the temperature-induced unfolding/aggregation of HCA II (in the absence of GroEL) on one hand and the GroEL-HCA II interaction on the other, and (2) the sample was incubated for 7 min before starting the measurement to make sure the GroEL-HCA II complex was established.A second set of samples of F147R1, K213R1, and F147R1/K213R1, tailored to facilitate the estimation of distances from EPR data, was prepared. For measurements at 20 °C, labeled mutants (without GroEL) were prepared in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5, with subsequent addition of 40% (w/w) sucrose. For measurements at 60 °C, labeled mutants were prepared without/with GroEL in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5, with subsequent addition of 52.5% (w/w) sucrose. The final sample volume was 300 μL. Measurements were performed using a scan width of 300 G and a measurement time of 90–180 min. The same measurement procedures as for the first set were used, except for a longer incubation time (11 min) and no monitoring of slow kinetics.Lineshape distortions from experimental conditions were avoided by using a modulation amplitude less than 1/3 of the linewidth of the mI = 0 nitrogen hyperfine transition, a time constant less than 1/10 of the time spent to sweep the mI = 0 line, and a microwave power of 4 mW.

Analysis of EPR spectra in terms of side-chain mobility and interspin distance For the analysis of the doubly labeled mutant, spectra of the two singly labeled mutants were added, i.e., F147R1 + K213R1. If the protein concentration is kept constant at 6.8 μM and the degree of labeling is the same, the numbers of spins contributing to the spectra of the double mutant and sum of single mutants are equal (13.6 μM). To correct for differences in acquisition parameters and labeling degree, all spectra were normalized to a double integral equal to 1.Analysis of the EPR spectra in terms of the interspin distance between the nitroxide pair in F147R1/K213R1 was carried out using the “Distances” software developed by Altenbach and co-workers. This software is based on the strategy of using rigid-lattice conditions to estimate interspin distance distributions at ambient temperatures using a deconvolution method [36]. It was necessary to correct the spectra of F147R1/K213R1 with a small fraction of non-interacting spins likely due to incomplete labeling of the cysteines. Derived interspin distance distributions are expressed as normalized distance populations.

Results

The HCA II structure is dominated by a 10-stranded β-sheet that spans the entire molecule. The central part of the sheet comprising β-strands 3–7 constitutes a very hydrophobic region [20, 37]. The β-sheet is composed of predominantly antiparallel β-strands. However, there is one pronounced topological breakpoint where β-strands 6 and 7 form a parallel motif. The strands are composed of residues 140–147 and 206–213, and are therefore separated in the primary sequence by 58 residues. This intervening stretch of residues (148–205) forms one helix, β-strands 1 and 8 and some connecting structure. In this work, we used SDSL of the single mutants F147C and K213C and the double mutant F147C/K213C to investigate the conformational consequences of HCA II when binding to GroEL. The sites, F147 in β-strand 6 and K213 in β-strand 7, are situated very closely (Cβ–Cβ distance only 8.8 Å) [38, 39] in the tertiary structure, in the central part of the topological breakpoint (Fig. 1).

The magnetic dipolar interaction between the two spin labels was used to monitor the interspin distance [29]. Changes in the dipolar interaction can result in large spectral changes, making the technique particularly useful to study conformational changes [40, 41]. In addition, the possibility to obtain quantitative intra-protein distances is certainly of value in studies of protein structure [31]. In order to monitor the dynamic GroEL-induced structural effects on HCA II, the experiments require solution measurements at physiological to mildly denaturing temperatures (20–50 °C). Under these conditions, the Fourier deconvolution distance analysis method [42], based on the rigid-lattice condition, is applicable if the rotational correlation time of the interspin vector is long enough [36]. The estimated useful distance range of ∼8–20 Å for this method with frozen samples [30] can also be achieved at physiological temperatures depending on protein size and solvent viscosity [36]. This analysis technique has been applied at room temperature in studies of light-dependent structural changes in rhodopsin [43], the arrangement of subunits and ordering of β-strands in an amyloid structure of transthyretin [44], and the phosphorylation-triggered domain separation in NarL [45].

In this work, EPR lineshapes from spin-labeled HCA II in its native and molten-globule conformations, and when bound to GroEL, were compared and analyzed in terms of side chain mobility, magnetic dipolar interaction, and distance.

Conditions for HCA II binding to GroEL

In order to bind to GroEL, HCA II needs to be partially unfolded to the molten globule state [10, 21]. We therefore used moderately denaturing conditions using elevated temperature (50 °C), which is above the melting temperature, Tm, of the HCA II mutants but below the Tm of GroEL, which denatures above 60 °C (Tm of 63–64 °C) [46]. The Tm, of the mutants were in the range 35–50 °C in the absence and 34–46 °C in the presence of GroEL (Table 1). Sucrose was found to increase the stability of HCA II at 50 °C (showing residual enzyme activity for the mutants), but at 60 °C, there was no measurable activity for the F147C/K213C and F147C mutants, and >80% of the activity was lost for the K213C mutant. Hence, in the presence of sucrose, EPR spectra were collected for samples incubated at 60 °C. This temperature was selected based on sucrose-induced stabilizing effects on seven other proteins, where the stabilizing effect of 50% sucrose (1.5 M) should render a Tm shift of ∼10 °C [47, 48]. In accordance with this, GroEL should withstand the 60 °C temperature by the stabilizing effect caused by 52.2% sucrose.

Table 1.

Midpoints of thermal denaturation (Tm) of HCA II mutants in the absence and presence of GroEL at equimolar concentration (see details in “Materials and methods” section)

| Mutant | Tm (°C)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Mutant | Mutant + GroEL | |

| F147C-R1 | 35 | 34 |

| K213C-R1 | 50 | 46 |

| F147C/K213Cb | 46 | 45 |

aDetermined by tryptophan fluorescence

bUnlabeled mutant

EPR spectra for mutants in the native state indicate preserved structure

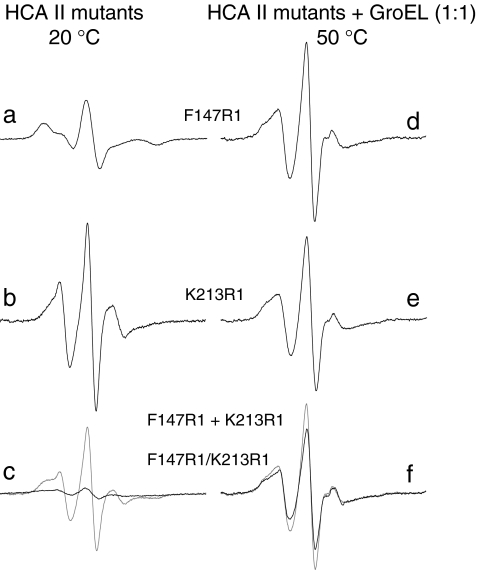

Figure 2 presents EPR spectra for F147R1, K213R1, and F147R1/K213R1 at 20 °C where HCA II is in the native state. The broad spectrum of F147R1 is representative of an immobilized spin label, which is normally the signature of a buried site such as F147 (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, the spectrum of K213R1 clearly shows the nitroxide triplet, characteristic of a mobile spin label, as expected from the surface-located K213 site (Fig. 2b). The double mutant F147R1/K213R1 shows a very broad EPR lineshape (Fig. 2c, black trace), which is the resulting signal from both spin labels. This broad spectrum differs substantially in line width and amplitude compared with the spectrum of F147R1 + K213R1, i.e., the sum of the single-mutant spectra (Fig. 2c, gray trace). Magnetic dipolar interaction leads to spectral broadening to an extent dependent on the interspin distance. Adding equimolar amounts of GroEL to the mutants at 20 °C produced no spectral changes (data not shown) as expected, since GroEL cannot bind HCA II in the native state [10].

Fig. 2.

EPR spectra of spin labeled HCA II mutants in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5 at 20 °C: a F147R1, b K213R1, and c F147R1/K213R1 (black trace) and F147R1 + K213R1 (summed spectra) (gray trace). EPR spectra of spin labeled HCA II mutants bound to GroEL at equimolar concentration in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5 at 50 °C: d F147R1, e K213R1, and f F147R1/K213R1 (black trace) and F147R1 + K213R1 (summed spectra) (gray trace). The same amplitude scale was used in all spectra, but spectra in c and f had first been divided by 2 to have all spectra representing one-spin systems. The scan width was 120 G

The structure is preserved at the topological break point in the molten globule state

The molten-globule intermediate of HCA II is very compact, has distorted tertiary structure, but possesses native-like secondary structure [33]. In the molten globule state, the diameter has been estimated to be ∼30% larger than for the native protein [12]. The HCA II molten-globule is highly prone to specific aggregation at temperatures above Tm [10], with the aggregation interface at β-strands 4–7 [3], and the aggregate size grows over time [12, 34]. It is important to characterize the molten-globule state of the mutants in the absence of GroEL, with the least possible interference from aggregation, to be able to isolate the structural effects from the GroEL interaction.

The molten-globule state of the spin-labeled mutants was induced by quickly raising the temperature from 20 to 50 °C. Because of the large surface area relative to the thickness of the flat cell, equilibration of the sample temperature was fast. One-scan spectra were recorded and the change in the peak-to-peak amplitude (Aptp) of the mI = 0 hyperfine line was used to follow the slow kinetics of the unfolding transition and subsequent aggregation up to 20 min (Fig. 3). By collecting the first spectrum ∼1 min after the rise in temperature, unfolding towards the molten-globule state is initiated and the influence from aggregation is at a minimum [10].

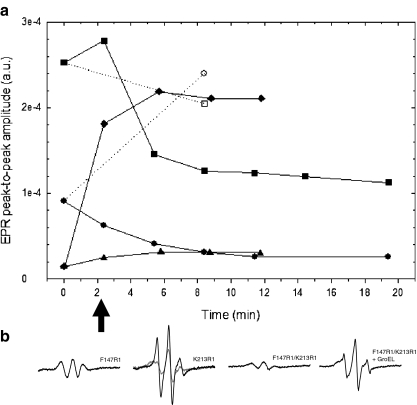

Fig. 3.

a EPR peak-to-peak amplitudes (Aptp) of the mI = 0 hyperfine line as a function of time after the 20 °C sample has been inserted into the resonator, preset to 50 °C: filled circles F147R1, filled square K213R1, filled triangle F147R1/K213R1, and filled diamond F147R1/K213R1 and GroEL, all in 0.1 M Tris–H2SO4, pH 7.5. All Aptp values were normalized to the same parameter set to allow comparison (see “Materials and methods” section). Aptp values at 0 min were taken from spectra measured at 20 °C (Fig. 2). Time values of data obtained at t > 0 correspond to the time when the center of the mI = 0 line was swept. For comparison, Aptp values from single mutants equilibrated at 50 °C in the presence of GroEL were included: open circles GroEL-F147R1 and open squares GroEL-K213R1. Lines were displayed for guidance. b The first one-scan EPR spectra taken after samples were introduced to 50 °C. The scan was started after 1 min and corresponding Aptp values are marked with an arrow in a. For K213R1, the last spectrum taken (after 18 min) is shown for comparison (gray trace). The same y-axis scale was used for all spectra

The Aptp of F147R1 decreases and levels out smoothly at 50 °C over the studied time period (Fig. 3a). Already after ∼1–3 min, the spectral features of the native state are replaced by a rather different spectrum (Fig. 3b), and judging from its line width and reduced amplitude, there is clear dipolar interaction due to spins in close proximity within the aggregate, which dominates over the spectral features of the fraction of immobilized non-interacting R1 side chains. The presence of position 147 at the aggregation interface is well in accordance with previous data showing that position 146 was a part of the aggregation interface during thermal denaturation [12]. Aptp of K213R1, on the other hand, shows an early mobility increase of the spin label from the elevated temperature at this surface-exposed site (Fig. 3b, black trace), followed by the gradual development of a second component that is broader than the first one (Fig. 3b, gray trace). The broader component probably originates from the gradual immobilization of the local motion of K213R1 approaching that of a fully immobilized R1 side chain (note that Aptp after 18 min was similar to that of F147R1 in the native state). A reduced overall protein tumbling (global motion) of HCA II was previously measured upon aggregate formation [34]. The very broad spectrum of F147R1/K213R1 is subject to minor changes and the slight increase in Aptp is due to the combined effects of increased temperature, reduced compactness, and aggregation on the motion of the spin labels. The strongly interacting spins of this mutant are quite insensitive to the reduced global motion from aggregation, since the motional broadening effect on the spectrum is smaller than the dipolar one in this motional regime.

An important finding from Fig. 3 is that thermal unfolding of the mutants to the molten-globule state (and the effects of aggregation) does not disrupt the structure in the region of β-strands 6 and 7. An increased distance between positions 147 and 213 would give rise to a weaker dipolar interaction, and hence, a much larger Aptp and narrower line shape of the spectrum than what is seen in Fig. 3b (F147R1/K213R1). Such a radical spectral change was, however, observed first after unfolding the double mutant beyond the molten-globule state (in 5 M GuHCl at 20 °C), which resulted in a narrow three-line spectrum from the non-interacting R1 moieties, distant in the unfolded protein (data not shown). Visual inspection of the samples (HCA II in the absence of GroEL) after the 50 °C measurements indeed revealed opalescent to precipitated samples, i.e., clear evidence of aggregate formation. The cell had to be carefully rinsed with 5 M GuHCl followed by buffer washing prior to every new experiment to eliminate the protein aggregates and to avoid their contaminating broad EPR signature.

Interaction with GroEL dislocates the β-strands at the topological break point

It is well established that, when GroEL is present at 50 °C, the molten-globule intermediate of HCA II will bind to GroEL rather than aggregate [10–12, 21]. This was found to have dramatic consequences for the mobility of the spin labels at the studied sites, primarily in the central β-strands 4–7. EPR spectra for F147R1, K213R1, and F147R1/K213R1 upon interaction with GroEL at 50 °C are shown in Fig. 2d–f. The changes in spin-label mobility, in terms of Aptp, from the native to the GroEL-bound mutant state, are also illustrated in Fig. 3a (dashed traces). As expected, none of the samples with GroEL present had an opalescent appearance after the measurements at 50 °C. Hence, the mutants bind to GroEL and are protected from aggregation. At position 147, the spin label clearly experiences an increased motion, as judged from the narrower spectral lineshape (Fig. 2d), compared with the native state of the protein where the label was buried (Fig. 2a). Such a reduction in compactness of the local protein structure was not observed at 50 °C in the absence of GroEL; thus, it points to a GroEL-induced unfolding of the bound substrate. For position 213, a slightly broader spectrum is obtained (Fig. 2e) in the GroEL-bound state, which means a somewhat immobilized spin label, indicative of a reduced surface exposure compared to the native state (Fig. 2b). Actually, the lineshapes of GroEL-F147R1 and GroEL-K213R1 are very similar (Fig. 2d, e). Thus, the labels at both positions are exposed to a structural surrounding of similar compactness in the GroEL-bound state. This is well in accordance to our previous study, where the peripheral positions became more rigid and buried positions were exposed during interaction with GroEL [10]. The binding of F147R1/K213R1 to GroEL produces a striking effect on the EPR signature (Fig. 2f, black trace) when compared with the broad spectra of the native and molten-globule states (Fig. 2c, black trace, and Fig. 3b, respectively). The spectrum is very similar to that of GroEL-F147R1 + GroEL-K213R1 (Fig. 2f, gray trace), and such a narrow lineshape of the double mutant spectrum can only be attributed to a substantial loss of dipolar interaction between the two spin labels.

How can we assign this spectral effect to GroEL-induced conformational changes rather than to thermal unfolding to the molten-globule state alone? Figure 3a (diamonds) shows the increase in Aptp over time; after that, F147R1/K213R1 has been exposed to 50 °C in the presence of GroEL, reaching a stable level with mobile separated spin-labels. The one-scan spectrum of F147R1/K213R1 in the presence of GroEL taken 1 min after the temperature increase presents a narrow lineshape very different from that of F147R1/K213R1 in the absence of GroEL. The spectrum from the double mutant in the absence of GroEL represents the molten-globule state with preserved interspin distance (Fig. 3b). This strongly implies that the increased inter-residue distance is a result of GroEL-induced stretching of the substrate protein. As a further control, we added GroES (2:1 over GroEL) and 1 mM Mg-ATP to the samples at 50 °C, which resulted in loss of signal due to formation of an opalescent sample, resulting from aggregation of HCA II (data not shown), showing that HCA II can be forced to release from the GroEL complex even at elevated temperatures, but then fails to refold due to aggregation. Hence, no EPR measurements were performed on the complete HCA II-GroEL/ES/ATP complex.

Analysis of interacting spin pairs in terms of distance

At physiological temperatures, the overall tumbling motion of HCA II itself results in partial or complete averaging of the dipolar interactions [49]. Another consideration is the internal motion of the side chain R1 relative to the protein, which modulates the magnetic anisotropies and varies in correlation time depending on the local protein structure. In general, R1 has a relatively constrained local motion compared to other spin labels [34, 49–53], and this motion has been found to have little effect on the magnetic dipolar interaction [36]. Thus, the extent of the dipolar averaging depends on the interspin distance relative to the rotational correlation time (τR) of the protein.

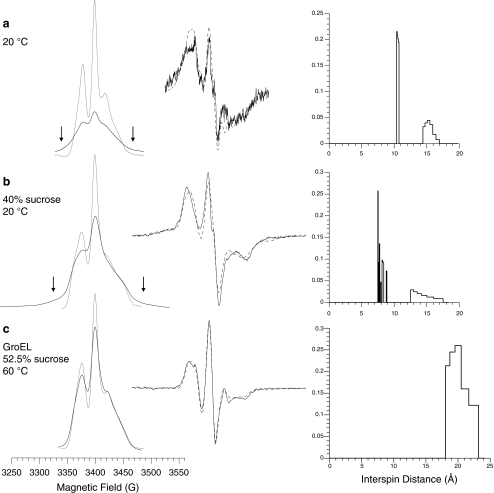

Figure 4 shows the absorption spectra for a number of F147R1/K213R1 samples, together with the corresponding sum of single-mutant spectra (left). In addition, the simulated and experimental first-derivative double-mutant spectra (middle) and the derived interspin distance distribution (right) are presented. In each case, the simulated spectrum is in acceptable agreement with the experimental spectrum of the double mutant. At 20 °C (Fig. 4a), the obtained bimodal distance distribution has one population at ∼10.5 Å with narrow distribution and another population at ∼15 Å with broader distribution. The existence of strongly interacting spin pairs is revealed by the broad component in the absorption spectrum of the double mutant only (Fig. 4a, arrows). At 50 °C in the presence of GroEL, the increased interspin distance that is expected from the diminished dipolar broadening could not be quantified due to the low sensitivity of the method in this motional regime. Thus, quantitative distance analysis usually demands reduced overall motion of the protein to prevent averaging of the dipolar anisotropy. Hence, by increasing the viscosity of the solvent, the sensitivity for weakly interacting spins can be improved. This will also increase the precision in the simulation of strong dipolar interactions. Hubbell and co-workers studied T4 lysozyme mutants, doubly labeled at solvent-exposed sites, in 40% sucrose solutions, and concluded that a τR of ∼30 ns (cf. ∼6 ns in buffer) was long enough to measure distances up to ∼20 Å [36]. For the slightly larger protein HCA II (r ≈ 20 Å), the addition of 40% sucrose (η ≈ 6.3 mPa s) [54] gives even better conditions (τR ≈ 53 ns; cf. ∼8 ns in buffer) for analysis of data obtained at 20 °C. Due to the increased stability of the HCA II mutants in solutions containing sucrose, measurements of the GroEL-induced effects on HCA II had to be performed at 60 °C to induce the molten-globule state. Consequently, 52.5% sucrose was used for these samples to maintain η ≈ 6.3 mPa s.

Fig. 4.

Left part, absorption EPR spectra of F147R1/K213R1 (black trace) and F147R1 + K213R1 (gray trace). All spectra are plotted with reference to a 300 G field scan. The vertical arrows denote regions of spectral broadening due to dipolar interaction. Middle part, first-derivative EPR spectra of F147R1/K213R1 together with simulated spectra from the distance analysis (dashed line). All spectra are plotted with reference to a spectral width of 200 G. Right part, derived interspin distance distributions expressed as normalized distance populations. a At 20 °C with no viscosity modifying agent, b with 40% sucrose at 20 °C, and c with 52.5% sucrose and equimolar amounts of GroEL at 60 °C

At 20 °C, a significantly broader absorption spectrum is seen for the spin-labeled double mutant in sucrose-containing solution compared with that of the sum of single mutants (Fig. 4b, arrows), which again points to a magnetic dipolar interaction between the spin labels at F147 and K213. A good simulation of the double mutant first-derivative spectrum was obtained from defining a bimodal distance distribution with a narrow component at ∼8 ± 2 Å and a broad component at ∼14 ± 2 Å. For reasons discussed above and the quality of the fit, this distance simulation is likely more accurate than the one presented in Fig. 4a.

Especially small distances have to be interpreted with the utmost caution because of the potential influence from the relative spin label conformations. The intrinsic motional restriction of the R1 side chain is caused by anchoring of the label through a disulfide group close to the backbone atoms. Hereby, a significant change in dipolar coupling is likely caused by a change in tertiary contact interactions, i.e., governed by a local two-state conformational heterogeneity of a partially exposed R1 group (K213R1) with different surroundings of two thermally populated rotameric states of the R1 side chain.

It is important to keep in mind that the contribution from through-space exchange interaction on the dipolar splitting was not specifically addressed in the distance analysis (pulsed-EPR techniques are required to separate the contributions from dipolar and exchange coupling [55]. The effect is negligible at ≥14 Å [56], but can be significant at shorter distances, such as around 8 Å, causing the determined interspin distance to be somewhat smaller than the “true” distance (if exchange was considered). Thus, the determined distances in this work should be regarded as estimates and not absolute quantitative numbers.

The estimated interspin distance for F147R1/K213R1 in the native state, and in particular that of the narrow population, is very close to the predicted distance from the crystal structure where the Cβ–Cβ distance is 8.8 Å [38, 39]. However, a more accurate comparison would be to compare the interspin distance with that obtained from structural molecular modeling including the spin labels [57]. This has, however, not been performed in the current work.

The spectra of the mutants when partly unfolded HCA II interacted with GroEL at 60 °C in sucrose-containing solution reveal that the spin-labeled double mutant produces a spectrum which is only slightly broader than that of the sum of single mutants (Fig. 4c). Nevertheless, in the absence of dipolar interaction, the broad component likely originating from the overall tumbling of the protein complex is still well emphasized in the spectra from the sucrose-containing samples due to the reduced motional averaging of the magnetic anisotropy. From the distance simulation, an average spin–spin distance of ∼20 Å was calculated, suggesting a distance increase of ∼12 or ∼6 Å, respectively, from the two distance populations seen in the native state at 20 °C. CW EPR distance analysis with deconvolution methods is generally considered to be effectively blind to distances longer than 20 Å; however, a recent study has shown that the upper limit for accurate distances from such methods is even lower, 15–17 Å [58]. This underlines the rather qualitative distance measure obtained for this sample. Due to these limitations, the obtained data and analysis are also consistent with a transition from a defined initial state that binds to GroEL, followed by a very broad conformational ensemble as the final state with increased distances compared to the molten globule.

The changes in experimental conditions (52.5% sucrose and 60 °C) that were introduced to obtain quantitative distance information may have influenced the characteristics of HCA II unfolding, the binding to GroEL, and the function of GroEL. This is, however, less likely because, qualitatively, the increased spin–spin separation induced by GroEL was very similar to that obtained in buffer at 50 °C.

Discussion

The central structure of HCA II is dominated by antiparallel β-strands, but a topological breakpoint between β-strands 6 and 7 renders these two strands parallel. The central part of the β-sheet (β-strands 4–7) of HCA II has been shown to be a nucleation site for highly specific protein aggregation [3, 12]. The reported structures for amyloid fibrils of Aβ 1–42 and the yeast prion protein Het-s report on a cross-β-sheet structure composed of parallel β-strands [59, 60] suggest that parallel β-strands are excellent propagation motifs for protein aggregates. It is of interest to know to what extent this potential feature for specific aggregation can be disrupted by GroEL, known to possess unfoldase activity.

GroEL recognition and binding

The present study shows, in agreement with our previous findings, that binding of GroEL to HCA II has dramatic consequences for the HCA II conformation. Several surface regions of the molten-globule state of HCA II are grasped by the apical domains of GroEL. Sites that have been experimentally shown to be involved are located at positions W16, H64, S56, F176, K213, and W245 [10, 12]. These residues are widely distributed throughout the HCA II structure both in the primary sequence and the folded structure, and they are all surface-exposed: W16 in the N-terminal region, H64 in the opening to the active site in the central part of the protein, S56 and F167 on the edge of β-strands 2 and 3, respectively, K213 at the edge of β-strand 7, and W245 in an exposed loop position. This indicates very promiscuous recognition of HCA II by GroEL where, in essence, GroEL “swallows” HCA II (Fig. 5a). The apical domain opening is 45 Å in diameter and the diameter of the molten-globule state of HCA II is in the range 50–60 Å. Our data strongly support a multivalent binding of HCA II, as was also shown to be the case for binding of MDH and Rubisco [27, 61]. The multi-valence binding was recently shown for GroEL bound MDH to invoke three or four apical domains on one side of the GroEL ring. The captured substrate was in close contact to the apical domains but also included binding deep down into the GroEL cavity, and could extend up to the periphery of the ring entrance [27].

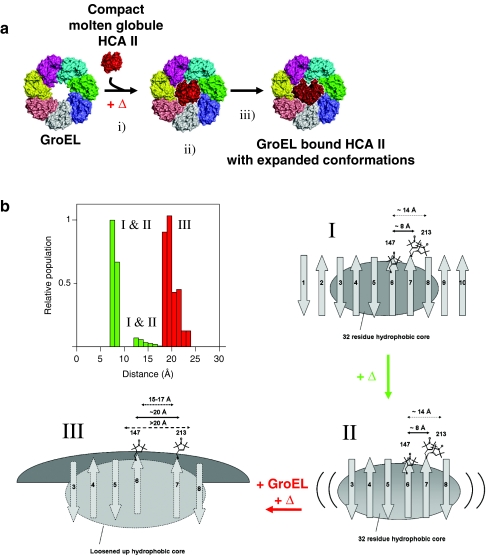

Fig. 5.

a Schematic top view structural model showing GroEL binding-induced unfolding of HCA II. i The thermally induced molten globule is captured by multiple valences to the GroEL apical domains. ii Initially, the molten globule has preserved central strand compactness, and iii the GroEL induced expansion of the central core of the bound substrate. b Cartoon representations of the topography of the native (I), molten globule (II), and GroEL bound HCA II (III). Distance distributions between position F147R1 and K213R1 (top left image). The capital roman numerals refer to the conformational states in the cartoon. I In the native state (20 °C) (top right cartoon), the ten stranded β-sheet with antiparallel arrangement between β-strands 1–6 and between β strands 7–9 are indicated, together with the parallel arrangement of β-strands 6 and 7 forming a topological breakpoint. The two calculated spin–spin distance populations of ∼8 Å and ∼14 Å are indicated. II The central core comprising residues from strands 3–8 are preserved in the molten globule state formed at elevated temperature [37] (lower right cartoon), as well as the native state distance between residues F147R1 and K213R1, with distances of ∼8 Å and ∼14 Å from spin–spin EPR measurements. III The GroEL bound state (bottom left cartoon) shows the GroEL-induced separated topological breakpoint indicated by three distance arrows. The short arrow includes the uncertainties of CW EPR distance analysis with deconvolution methods (often limited to 15–17 Å distances [58] the second arrow is taken from our calculated distance distribution ∼20 Å, and the third arrow denotes the possibility that the true distance is >20 Å, where the method is irrefutably blind

GroEL dislocates the substrate protein topology analogous to an “accordion player”

As a consequence of GroEL binding (even in the absence of GroES and ATP), the bound HCA II protein undergoes partial unfolding of its interior core. Previous measurements together with this work show that positions located in the core of HCA II, W97, L118, W123, A142, I146, F147, and C206, are all becoming more exposed and flexible as a consequence of the interaction with GroEL [10, 12]. This is most likely accomplished through binding-induced partial unfolding of HCA II (Fig. 5a) in an expanded GroEL cavity [11]. Alteration of the GroEL conformation during substrate protein binding was corroborated in analysis of cryo-EM images of the MDH-GroEL complex, showing asymmetric dislocation of 3–4 apical domains with the captured substrate [27]. In previous fluorescence experiments measuring the compactness of HCA II, under similar conditions to those reported here, we obtained a 29% increase in the global diameter of HCA II from thermal denaturation of the native protein to the molten globule. The GroEL-bound state compared to the native state showed 53% increase in the diameter of HCA II [12]. It has previously been shown by H/D exchange and NMR that very modest protection factors are present in substrate proteins bound to GroEL, but having a native-like topology of the substrate protein [22, 23].

In this work, we used SDSL for intramolecular distance estimations in solution to show that the topological breakpoint in the center of the 10-stranded β-sheet of HCA II, namely, β-strands 6 and 7, are preserved in the molten globule, at a distance as small as ∼8 Å, and a second distance shows a native state and molten globule state distance of ∼14 Å. These spin–spin distances become dislocated up to >20 Å (in the range of the limit of the EPR spin–spin dipolar coupling method: 15 to >20 Å) upon GroEL binding (Fig. 5b). If we assume that all differences between the single-labeled mutants and the double mutant in terms of EPR line shape broadening are due to spin–spin interactions, this would (at the longest calculated distance difference: 8 and 20 Å) correspond to a 2.5-fold increase in distance between these sites induced by GroEL binding.

From data presented in this work together with our previous investigations, it is compelling that GroEL “swallows” the aggregation-prone molten globule HCA II molecule with preserved topology of the central parallel β-strands 6 and 7. Upon binding to GroEL, the chaperonin induces extensive stretching of the central parallel β-strands analogous to playing an accordion (Fig. 5b). A strikingly similar but more dramatic structural domain-separation by the chaperonin TriC of bound β-actin was recently shown to be necessary for productive folding of β-actin [13, 14]. That model is analogous to structural observations of TriC captured α-actin from cryo electron microscopy from the Valpuesta group [62]. Furthermore, biochemical and structural studies of folding incompetent mutant alanine glyoxylate aminotransferase co-expressed in Escherichia coli revealed a non-native extended conformation that crosses the GroEL central cavity and strongly advocates a functional model in which GroEL promotes folding through a forced unfolding mechanism [63]. Hence, the dislocation of the central part of HCA II through GroEL-induced stretching reported in this work is a very plausible mechanism by which the substrate is provided with a new chance to fold correctly and avoid misfolding side steps off the productive folding route. The binding-induced unfolding model (in the absence of ATP) for the chaperonins provides a new view of these biologically essential folding machines, without the consumption of vital energy, which is especially important during stressed conditions.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Anders Lund for giving us access to the EPR lab at IFM-Chemical Physics, Linköping University and Professor Sandra S. Eaton, University of Denver, for advice concerning EPR data analysis. We acknowledge Professor Mikael Lindgren and Dr. Malin Persson for valuable discussions and advice. We also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Christian Altenbach, University of California, Los Angeles, for providing his software for determining inter-residue distances. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (PH), the Swedish Research Council (BHJ, PH, and UC), and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (BHJ, PH, and UC). PH is a Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Research Fellow supported by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Abbreviations

- Aptp

peak to peak amplitude

- EPR

Electron paramagnetic resonance

- FRET

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GuHCl

Guanidine hydrochloride

- HCA II

Human carbonic anhydrase II

- MTSSL

(1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl)-methanethiosulfonate spin label

- R1

Cysteine side chain labeled with MTSSL

References

- 1.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammarström P, Persson M, Freskgård PO, Mårtensson LG, Andersson D, Jonsson BH, Carlsson U. Structural mapping of an aggregation nucleation site in a molten globule intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32897–32903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiseman RL, Powers ET, Buxbaum JN, Kelly JW, Balch WE. An adaptable standard for protein export from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 2007;131(4):809–821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.London J, Skrzynia C, Goldberg ME. Renaturation of Escherichia coli tryptophanase after exposure to 8 M urea. Evidence for the existence of nucleation centers. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47:409–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campioni S, Mossuto MF, Torrassa S, Calloni G, Laureto PP, Relini A, Fontana A, Chiti F. Conformational properties of the aggregation precursor state of HypF-N. J Mol Biol. 2008;379(3):554–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saibil HR, Zheng D, Roseman AM, Hunter AS, Watson GMF, Chen S, auf der Mauer A, O'Hara BP, Wood SP, Mann NH. ATP induces large quaternary rearrangements in a cage-like chaperonin structure. Curr Biol. 1993;3:265–273. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90176-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zahn R, Perrett S, Fersht AR. Conformational states bound by the molecular chaperones GroEL and secB: a hidden unfolding (annealing) activity. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:43–61. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwich AL, Fenton WA. Chaperonin-mediated protein folding: using a central cavity to kinetically assist polypeptide chain folding. Q Rev Biophys. 2009;42(2):83–116. doi: 10.1017/S0033583509004764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Persson M, Lindgren M, Hammarström P, Svensson M, Jonsson BH, Carlsson U. EPR mapping of interactions between spin-labeled variants of human carbonic anhydrase II and GroEL: evidence for increased flexibility of the hydrophobic core by the interaction. Biochemistry. 1999;38:432–441. doi: 10.1021/bi981442e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammarström P, Persson M, Owenius R, Lindgren M, Carlsson U. Protein substrate binding induces conformational changes in the chaperonin GroEL. A suggested mechanism for unfoldase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22832–22838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammarström P, Persson M, Carlsson U. Protein compactness measured by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Human carbonic anhydrase II is considerably expanded by the interaction of GroEL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21765–21775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villebeck L, Persson M, Luan SL, Hammarström P, Lindgren M, Jonsson BH. Conformational rearrangements of tail-less complex polypeptide 1 (TCP-1) ring complex (TRiC)-bound actin. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5083–5093. doi: 10.1021/bi062093o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villebeck L, Moparthi SB, Lindgren M, Hammarström P, Jonsson BH. Domain-specific chaperone-induced expansion is required for beta-actin folding: a comparison of beta-actin conformations upon interactions with GroEL and tail-less complex polypeptide 1 ring complex (TRiC) Biochemistry. 2007;46:12639–12647. doi: 10.1021/bi700658n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slepenkov SV, Witt SN. The unfolding story of the Escherichia coli Hsp70 DnaK: is DnaK a holdase or an unfoldase? Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1197–1206. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zolkiewski M. A camel passes through the eye of a needle: protein unfolding activity of Clp ATPases. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1094–1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viitanen PV, Donaldson GK, Lorimer GH, Lubben TH, Gatenby AA. Complex interactions between the chaperonin 60 molecular chaperone and dihydrofolate reductase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9716–9723. doi: 10.1021/bi00104a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zahn R, Perrett S, Stenberg G, Fersht AR. Catalysis of amide proton exchange by the molecular chaperones GroEL and SecB. Science. 1996;271:642–645. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid BG, Flynn GC. GroEL binds to and unfolds rhodanese posttranslationally. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7212–7217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlsson U, Jonsson BH. Folding of beta-sheet proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1995;5:482–487. doi: 10.1016/0959-440X(95)80032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persson M, Carlsson U, Bergenhem NCH. GroEL reversibly binds to, and causes rapid inactivation of, human carbonic anhydrase II at high temperatures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1298:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(96)00125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg MS, Zhang J, Sondek S, Matthews CR, Fox RO, Horwich AL. Native-like structure of a protein-folding intermediate bound to the chaperonin GroEL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1080–1085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J, Walter S, Horwich AL, Smith DL. Folding of malate dehydrogenase inside the GroEL-GroES cavity. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:721–728. doi: 10.1038/90443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shortle D, Ackerman MS. Persistence of native-like topology in a denatured protein in 8 M urea. Science. 2001;293:487–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1060438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gervasoni P, Staudenmann W, James P, Plückthun A. Identification of the binding surface on beta-lactamase for GroEL by limited proteolysis and MALDI-mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11660–11669. doi: 10.1021/bi980258q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shtilerman M, Lorimer GH, Englander SW. Chaperonin function: folding by forced unfolding. Science. 1999;284:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elad N, Farr GW, Clare DK, Orlova EV, Horwich AL, Saibil HR. Topologies of a substrate protein bound to the chaperonin GroEL. Mol Cell. 2007;26:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammarström P, Jonsson BH (2005) Protein denaturation and the denatured state. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Wiley, New York (doi:10.1038/npg.els.0003003)

- 29.Berliner LJ, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, editors. Biological magnetic resonance, Vol. 19: distance measurements in biological systems by EPR. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persson M, Harbridge JR, Hammarström P, Mitri R, Mårtensson LG, Carlsson U, Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Comparison of electron paramagnetic resonance methods to determine distances between spin labels on human carbonic anhydrase II. Biophys J. 2001;80:2886–2897. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeschke G, Polyhach Y. Distance measurements on spin-labelled biomacromolecules by pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9:1895–1910. doi: 10.1039/b614920k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleissner MR, Brustad EM, Kálai T, Altenbach C, Cascio D, Peters FB, Hideg K, Schultz PG, Hubbell WL. Site-directed spin labeling of a genetically encoded unnatural amino acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(51):21637–21642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912009106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mårtensson LG, Jonsson BH, Freskgård PO, Kihlgren A, Svensson M, Carlsson U. Characterization of folding intermediates of human carbonic anhydrase II: probing substructure by chemical labeling of SH groups introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1993;32:224–231. doi: 10.1021/bi00052a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammarström P, Owenius R, Mårtensson LG, Carlsson U, Lindgren M. High-resolution probing of local conformational changes in proteins by the use of multiple labeling: unfolding and self-assembly of human carbonic anhydrase II monitored by spin, fluorescent, and chemical reactivity probes. Biophys J. 2001;80:2867–2885. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svensson M, Freskgard PO, Lindgren M, Boren K, Carlsson U. Mapping the folding intermediate of human carbonic anhydrase II. Probing substructure by chemical reactivity and spin and fluorescence labeling of engineered cysteine residues. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8606–8620. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altenbach C, Oh KJ, Trabanino RJ, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Estimation of inter-residue distances in spin labeled proteins at physiological temperatures: experimental strategies and practical limitations. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15471–15482. doi: 10.1021/bi011544w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammarström P, Carlsson U. Is the unfolded state the Rosetta Stone of the protein folding problem? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:393–398. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eriksson EA, Jones AT, Liljas A. Refined structure of human carbonic anhydrase II at 2.0 A resolution. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1988;4:274–282. doi: 10.1002/prot.340040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Håkansson K, Carlsson M, Svensson LA, Liljas A. Structure of native and apo carbonic anhydrase II and structure of some of its anion-ligand complexes. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90531-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anthony-Cahill SJ, Benfield PA, Fairman R, Wasserman ZR, Brenner SL, Stafford WF, Altenbach C, Hubbell WL, Grado WF. Molecular characterization of helix-loop-helix peptides. Science. 1992;255:979–983. doi: 10.1126/science.1312255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farrens DL, Altenbach C, Yang K, Hubbell WL, Khorana HG. Requirement of rigid-body motion of transmembrane helices for light activation of rhodopsin. Science. 1996;274:768–770. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rabenstein MD, Shin YK. Determination of the distance between two spin labels attached to a macromolecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8239–8243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Altenbach C, Cai K, Klein-Seetharaman J, Khorana HG, Hubbell WL. Structure and function in rhodopsin: mapping light-dependent changes in distance between residue 65 in helix TM1 and residues in the sequence 306-319 at the cytoplasmic end of helix TM7 and in helix H8. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15483–15492. doi: 10.1021/bi011546g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serag AA, Altenbach C, Gingery M, Hubbell WL, Yeates TO. Arrangement of subunits and ordering of beta-strands in an amyloid sheet. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:734–739. doi: 10.1038/nsb838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang JH, Xiao G, Gunsalus RP, Hubbell WL. Phosphorylation triggers domain separation in the DNA binding response regulator NarL. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2552–2559. doi: 10.1021/bi0272205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sot B, Bañuelos S, Valpuesta JM, Muga A. GroEL stability and function. Contribution of the ionic interactions at the inter-ring contact sites. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(34):32083–32090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Back JF, Oakenfull D, Smith MB. Increased thermal stability of proteins in the presence of sugars and polyols. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5191–5196. doi: 10.1021/bi00590a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JC, Timasheff SN. The stabilization of proteins by sucrose. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7193–7201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mchaourab HS, Oh KJ, Fang CJ, Hubbell WL. Conformation of T4 lysozyme in solution. Hinge-bending motion and the substrate-induced conformational transition studied by site-directed spin labeling. Biochemistry. 1997;36:307–316. doi: 10.1021/bi962114m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mchaourab HS, Lietzow MA, Hideg K, Hubbell WL. Motion of spin-labeled side chains in T4 lysozyme. Correlation with protein structure and dynamics. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7692–7704. doi: 10.1021/bi960482k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owenius R, Österlund M, Lindgren M, Svensson M, Olsen OH, Persson E, Freskgård PO, Carlsson U. Properties of spin and fluorescent labels at a receptor-ligand interface. Biophys J. 1999;77:2237–2250. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77064-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owenius R, Österlund M, Svensson M, Lindgren M, Persson E, Freskgård PO, Carlsson U. Spin and fluorescent probing of the binding interface between tissue factor and factor VIIa at multiple sites. Biophys J. 2001;81:2357–2369. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75882-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Langen R, Oh KJ, Cascio D, Hubbell WL. Crystal structures of spin labeled T4 lysozyme mutants: implications for the interpretation of EPR spectra in terms of structure. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8396–8405. doi: 10.1021/bi000604f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mathlouthi M, Reiser P, editors. Sucrose: properties and applications. London: Blackie; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weber A, Schiemann O, Bode B, Prisner TF. PELDOR at S- and X-band frequencies and the separation of exchange coupling from dipolar coupling. J Magn Reson. 2002;157:277–285. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2002.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiori WR, Millhauser GL. Exploring the peptide 3(10)-helix<–>alpha-helix equilibrium with double label electron spin resonance. Biopolymers. 1995;37:421–431. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sale K, Song L, Liu Y-S, Perozo E, Fajer P. Explicit treatment of spin labels in modeling of distance constraints from dipolar EPR and DEER. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9334–9335. doi: 10.1021/ja051652w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Banham JE, Baker CM, Ceola S, Day IJ, Grant GH, Groenen EJJ, Rogers CT, Jeschke G, Timmel CR. Distance measurements in the borderline region of applicability of CW EPR and DEER: a model study on a homologous series of spin-labelled peptides. J Magn Reson. 2008;191:202–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lührs T, Ritter C, Adrian M, Riek-Loher D, Bohrmann B, Döbeli H, Schubert D, Riek R. 3D structure of Alzheimer's amyloid-beta(1-42) fibrils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17342–17347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ritter C, Maddelein ML, Siemer AB, Lührs T, Ernst M, Meier BH, Saupe SJ, Riek R. Correlation of structural elements and infectivity of the HET-s prion. Nature. 2005;435:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nature03793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farr GW, Furtak K, Rowland MB, Ranson NA, Saibil HR, Kirchhausen T, Horwich AL. Multivalent binding of nonnative substrate proteins by the chaperonin GroEL. Cell. 2000;100:561–573. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Llorca O, McCormack EA, Hynes G, Grantham J, Cordell J, Carrascosa JL, Willison KR, Fernandez JJ, Valpuesta JM. Eukaryotic type II chaperonin CCT interacts with actin through specific subunits. Nature. 1999;402:693–696. doi: 10.1038/45294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albert A, Yunta C, Arranz R, Peña A, Salido E, Valpuesta JM, Martín-Benito J. Structure of GroEL in complex with an early folding intermediate of alanine glyoxylate aminotransferase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(9):6371–6376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]