Abstract

Methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP) catalyzes the hydrolytic cleavage of the N-terminal methionine from newly synthesized polypeptides. The extent of methionyl removal from a protein is dictated by its N-terminal peptide sequence. Earlier studies revealed that MetAPs require amino acids containing small side chains (e.g., Gly, Ala, Ser, Cys, Pro, Thr, and Val) as the P1’ residue, but their specificity at positions P2’ and beyond remains incompletely defined. In this work, the substrate specificities of Escherichia coli MetAP1, human MetAP1, and human MetAP2 were systematically profiled by screening against a combinatorial peptide library and kinetic analysis of individually synthesized peptide substrates. Our results show that although all three enzymes require small residues at the P1’ position, they have differential tolerance for Val and Thr at this position. The catalytic activity of human MetAP2 toward Met-Val peptides is consistently two orders of magnitude higher than that of MetAP1, suggesting that MetAP2 is responsible for processing proteins containing N-terminal Met-Val and Met-Thr sequences in vivo. At positions P2’ to P5’, all three MetAPs have broad specificity, but are poorly active toward peptides containing a proline at the P2’ position. In addition, the human MetAPs disfavor acidic residues at the P2’ to P5’ positions. The specificity data have allowed us to formulate a simple set of rules that can reliably predict the N-terminal processing of E. coli and human proteins.

Keywords: Methionine aminopeptidase, N-terminal processing, substrate specificity, kinetics, peptide library

Ribosomal protein synthesis is universally initiated with methionine (in eukaryotic cytoplasm) or N-formylmethionine (in prokaryotes, mitochondria, and chloroplasts). During protein maturation, the N-formyl group is removed by peptide deformylase, leaving methionine with a free NH2 group (1). Subsequently, the initiator methionine is removed from many but not all of the proteins by methionine aminopeptidase(s) (MetAPs). For example, in a cytosolic extract of Escherichia coli, only 40% of the polypeptides retain the initiator methionine, whereas the majority of the polypeptides display alanine, serine, or threonine at their N-termini (2). There are two types of MetAPs, MetAP1 and MetAP2. While eubacteria have only MetAP1 and archaea have only MetAP2, eukaryotes including yeast have both MetAP1 and MetAP2 in the cytoplasm and MetAP1D in the mitochondria (3). MetAP activities are essential for survival in both bacteria and yeast (4–6). As a result, there has been a renewed interest in designing specific inhibitors against bacterial MetAP1 as novel antibiotics (7–10). We and others have previously discovered that MetAP2 is the molecular target of fumagillin, a fungal metabolite and potent inhibitor of angiogenesis, validating MetAP2 as a novel target for anticancer treatment (11, 12). In fact, a semisynthetic analog of fumagillin, TNP-470, has entered Phase II clinical trial as an anticancer agent (13). TNP-470 preferentially inhibits endothelial cell growth in tumor vasculature by arresting the cell cycle in the late G1 phase (14, 15). Presumably, inhibition of MetAP2 by TNP-470 prevents the methionine removal from one or more critical proteins and therefore their maturation. However, the identity of these MetAP2-specific substrates is currently unknown.

N-terminal methionine removal is a co-translational process and occurs as soon as a polypeptide emerges from the ribosome (16). Previous studies indicate that the fate of the N-terminal methionine is dictated by the substrate specificities of MetAPs, which require Met as the P1 residue and amino acids with small side chains as the P1’ residue (e.g., Ala, Gly, Pro, Ser, Thr, or Val) (17–24). Amino acid residues at positions P2’ and beyond also play a role. For example, a hemoglobin variant with a proline at position 3 (P2’) retains the initiator methionine in vivo, whereas mutation of the proline to Arg or Gln leads to complete cleavage of the methionine (20). Chang et al. reported a two-fold difference in activity of purified yeast MetAP1 toward Met-Ala-Ile-Pro-Glu vs Met-Ala-Ile-Pro-Ser, which differ only at the P4’ position (21). These studies clearly demonstrate the existence of sequence specificity by MetAPs. However, because these studies employed the individual synthesis and activity assay of each peptide, the sequences that have been tested represent only a small fraction of the possible protein N-terminal sequence space and are generally limited to examine the specificity at the P1, P1’ and occasionally P2’ positions. One recent study by Frottin et al. has generated a more complete specificity profile of E. coli MetAP1 and Pyrococcus furiosus MetAP2, by synthesizing and assaying ∼120 short peptides (25). To our knowledge, no systematic study has been performed for any eukaryotic MetAPs. A potential approach to systematically determining the substrate specificity of a MetAP is to screen it against a combinatorial peptide library. This, however, has not been possible due to the technical difficulty in differentiating reaction products from unreacted substrates, which are both peptides with free N-termini. Herein, we report a novel peptide library screening strategy and its application to determine the sequence specificity of E. coli MetAP1, human MetAP1 and MetAP2. The specificity information should be useful in designing specific MetAP2 inhibitors as anticancer agents and compounds specific for the bacterial MetAP1 as antibacterial agents.

Materials and Methods

Materials and General Methods

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 DPX spectrometer at 300 and 75 MHz, respectively. Fmoc-protected L-amino acids were purchased from Advanced ChemTech (Louisville, KY), Peptides International (Louisville, KY), or NovaBiochem (La Jolla, CA). O-Benzotriazole-N,N,N',N'-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt) were from Peptides International. All solvents and other chemical reagents were obtained from Aldrich, Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), or VWR (West Chester, PA) and were used without further purification unless noted otherwise. N-(9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyloxy) succinimide (Fmoc-OSu) was from Advanced ChemTech. Phenyl isothiocyanate (PITC) was purchased in 1-mL sealed ampoules from Sigma-Aldrich, and a freshly opened ampoule was used in each experiment. N-(4-[4’-(Dimethylamino)phenylazo]benzoyloxy)succinimide (Dabcyl-OSu) was from ABD Bioquest (Sunnyvale, CA). Amino polyethylene glycol (PEGA) resin (0.4 mmol/g, 150–300 µM in water) was from Peptide International. Clear amide resin (90 µm, 0.23 mmol/g) was from Advanced ChemTech. α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (α-CCA) was purchased from Sigma and recrystallized prior to use. E. coli MetAP1 was purified from an E. coli strain overproducing the enzyme as previously described (26). Recombinant human MetAP1 and MetAP2 were expressed and purified as previously described (11, 26). Anti-Flag, anti-PGM1, and anti-TXNL1 antibodies were purchased from Sigma or Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA).

Synthesis of MetAP Library

The peptide library was synthesized on 2.0 g of PEGA resin (0.4 mmol/g, 150–300 µm in water). All of the manipulations were performed at room temperature unless otherwise noted. Synthesis of the N-1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohexylidene)ethyl (Dde) linker began with acylation of the resin bounded amine with glutaric anhydride (3.0 equiv) in 15 mL of CH2Cl2 containing diisopropylethylamine (1.1 equiv). After 3 h, the resin was washed with CH2Cl2 and the newly formed carboxylic acid was treated with 15 mL of CH2Cl2 containing 5,5-dimethylcyclohexanedione (4.0 equiv), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDCI, 2 equiv), and N,N-diaminopyridine (2 equiv) for 36 h. The excess reagents were removed by filtration and the beads were washed with CH2Cl2 (50 mL) and DMF (50 mL). Next, the resin was incubated with 1,5-diaminopentane (20 equiv) in 15 mL of CH2Cl2 to furnish the Dde linker. Coupling of the first amino acid and the rest of peptide synthesis followed standard Fmoc/HBTU chemistry using four equiv of Fmoc-amino acids. To construct the random region, the resin was split into the desired number of equal portions and each portion was coupled twice with 4 equiv of a different Fmoc-amino acid plus HBTU/HOBt/N-methylmorpholine (NMM) for 2 h at room temperature. To differentiate isobaric amino acids during MS analysis, 5% (mol/mol) CD3CO2D was added to the coupling reaction of Leu, whereas 5% CH3CD2CO2D was added to the coupling reaction of norleucine (27). After the coupling of the last random residue, the resin was pooled into three sub-libraries according to the identity of the last random residue. Sub-libraries I and II contained Ser and Thr as the N-terminal residues, respectively, while sub-library III contained an equimolar mixture of the other 16 L-α-amino acids excluding Ser and Thr. The three sub-libraries were separately coupled with 4 equiv of Fmoc-Met-OH and deprotected by treatment with the modified reagent K (TFA:phenole:H2O:thioanisole:ethanedithiol:anisole = 79:7.5:5:5:2.5:1). The resin-bound sub-libraries were washed exhaustively with CH2Cl2 and DMF, suspended in DMF, and stored under argon atmosphere at 4 °C.

N-Hydroxylsuccinimidyl 3-[4-(4-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoylamino]propionate (Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu)

To a 100 mL dry flask was added Dabcyl-OSu (0.366 mg, 1 mmol), DMF (25 mL), triethylamine (0.42 mL, 3.0 mmol), and β–alanine (0.091g, 1.02 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the solid residue was washed with H2O and then dried via azeotrope with toluene to give 0.322 g (88% yield) of a crude product. The crude product (0.322 g, 0.946 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (15 mL), to which N-hydroxysuccinimide (0.163 g, 1.42 mmol) and EDCI (0.272 g, 1.42 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred overnight and the solvent was removed under vacuum. The solid residue was dissolved in dichloromethane, washed with H2O, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give a red solid (0.372 g, 90% yield). 1H NMR (250 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.96-7.86 (m, 6H), 6.77 (d, 2H, J = 9.3), 3.92 (m, 2H), 3.11 (s, 6H), 3.00-2.95 (m, 2H), 2.89 (s, 4H). HRMS (ESI): Calcd for C22H24N5O5 (M++H) 438.1772, found 438.1764.

4-(4-Dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid hydrazide

To a solution of Dabcyl-OSu (0.366 g, 1 mmol) in DMF was added dropwise anhydrous NH2NH2 (31.4 µL, 1.0 mmol) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 20 min. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the solid residue was washed with H2O and dried under vacuum to give 0.253 g (89.4%) of product as a red solid. 1H NMR (400 Hz, DMSO-d6): δ 9.86 (s, 1H), 7.97-7.93 (m, 2H), 7.82-7.77 (m, 4H), 6.86-6.82 (m 2H), 4.55 (brs, 2H), 3.08 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 Hz, DMSO-d6): δ 165.3, 154.0, 152.9, 142.7, 133.6, 128.1, 125.1, 121.6, 111.6, 39.9. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C15H17N5ONa (M+ + Na) 306.1331, found 306.1323.

MetAP Library Screening (Method A)

A typical screening involved 20 mg of sub-library III (∼71,000 beads), which was transferred into a disposable Bio-spin column (2.0 mL). The resin was washed with DMF (5 × 1.8 mL), H2O (5 × 1.8 mL), and a MetAP screening buffer (30 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM CoCl2). After incubation with the screening buffer for 10 min, the resin was treated with 75–500 nM MetAP at room temperature for 30–180 min. The reaction was terminated by removing the enzyme solution (via filtration) and washing the resin with a 0.2 M EDTA solution (5 × 1.8 mL). After 10 min incubation with 0.2 M EDTA, the resin was washed with 1 M NaCl (5 × 1.8 mL) and incubated with 1 M NaCl for 10 min. The resin was next washed with H2O (5 × 1.8 mL) and DMF (5 × 1.8 mL) and treated with 1.2 equiv of 39:1 (mol/mol) Fmoc-OSu and Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu dissolved in a 9:1 (v/v) DMF: phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0) for 1.5 h. The resulting resin was washed with DMF (5 × 1.8 mL) and incubated with 20% piperidine in DMF for 5 and 15 min. The resin was washed with DMF (5 × 1.8 mL) and H2O (5 × 1.8 mL) and incubated overnight with 100 mg/mL CNBr in 70% formic acid at room temperature. After the overnight incubation, the resin was thoroughly washed with 70% HCOOH and transferred into a 60 × 15 mm Petri dish with H2O. After the addition of a drop of 6 M HCl into the Petri dish, the red colored beads were manually removed from the dish using a micropipette with the aid of a dissecting microscope. A control reaction without MetAP produced no colored beads.

MetAP Library Screening (Method B)

Sub-library I or II (typically 4.3 mg) was washed and treated with MetAP as described above. After the MetAP reaction, the resin was washed exhaustively with H2O and then treated with 2 equiv of NaIO4 dissolved in 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 5 min at room temperature. The reaction solution was removed and the resin was washed with H2O. The resin was suspended in 0.9 mL of 1% ethylene glycol in H2O and incubated for 10 min. The resin was washed with H2O (5 × 0.9 mL) and treated with 0.1 equiv of Dabcyl-NHNH2 in a 7:3 (v/v) mixture of 30 mM NaOAc buffer (30 mM, pH 4.5)/MeCN for 1.5 h at room temperature. The reaction solution was removed and the resin was washed with MeCN (5 × 0.9 mL) and DMF (5 × 0.9 mL). The resin was treated with 10 equiv of NaBH3CN in 0.9 mL of DMF containing 1% HOAc for 36 h. After that, the resin was washed with DMF (5 × 0.9 mL), H2O (5 × 0.9 mL) and transferred into a Petri dish with H2O. The solution was acidified with HCl and the red colored beads were manually removed from the library.

Peptide Sequencing by Partial Edman Degradation-Mass Spectrometry (PED-MS)

Positive beads derived from the same screening experiment were pooled into a single reaction vessel, suspended in 160 µL of 2:1 (v/v) pyridine/water containing 0.1% triethylamine, and mixed with an equal volume of 80:1 (mol/mol) PITC and Fmoc-OSu in pyridine (625 mM of PITC and 7.8 mM of Fmoc-OSu). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 6 min at room temperature, and the beads were washed sequentially with pyridine, CH2Cl2, and TFA. The beads were treated twice with 500 µL of TFA for 6 min each. The beads were washed with CH2Cl2 and pyridine and the PED cycle was repeated 5 (for hits from method A) or 6 times (for hits from method B). Finally, the beads were treated twice with 1 mL of 20% piperidine in DMF at room temperature (5 min each). The beads were washed exhaustively with water and transferred into individual microcentrifuge tubes (1 bead/tube). Each bead was treated with 10 µL of 1.5% hydrazine in THF/H2O (1:1) at room temperature for 15 min. The solution was acidified by the addition of 10 µL of 7% TFA in H2O. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the released sample was dissolved in 5 µL of 0.1% TFA in water. One µL of the peptide solution was mixed with 2 µL of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in acetonitrile/0.1% TFA (1:1), and 1 µL of the resulting mixture was spotted onto a 384-well sample plate. Mass spectrometry was performed at Campus Chemical Instrument Center of The Ohio State University on a Bruker III MALDI-TOF instrument in an automated manner. The data obtained were analyzed by Moverz software (Proteometrics LLC, Winnipeg, Canada).

Synthesis of Individual Peptides

Individual peptides were synthesized using standard solid phase Fmoc/HBTU chemistry. Each peptide was synthesized on 100 mg of CLEAR-amide resin (0.49 mmol/g). Ninhydrin test was used to monitor the completion after each coupling reaction. After cleavage and deprotection with a modified reagent K (7.5% phenol, 5% water, 5% thioanisole, 2.5% ethanedithiol, 1% anisole in TFA), the crude peptides were precipitated in cold diethyl ether and purified by reversed-phase HPLC on a C18 column (Varian 120 Ǻ, 4.6 × 250 mm). The identity of the peptides was confirmed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric analyses.

MetAP Activity Assay

A typical assay reaction (total volume of 100 µL) contained 1x MetAP reaction buffer (30 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM CoCl2) and 0–200 µM peptide substrate. The reaction was initiated by the addition of MetAP (final concentration 5–1000 nM) and quenched after 10–90 min with the addition of three drops of TFA. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge for 5 min and the clear supernatant was analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC on an analytical C18 column (Vydac C18 300 Å) eluted with a linear gradient of acetonitrile in water containing 0.05% TFA (10–40% acetonitrile in 18 min). The percentage of substrate-to-product conversion was determined from the peak areas of the remaining substrate and the reaction product (monitored at 214 nm) and kept at <20%. The initial rates were calculated from the conversion percentages and plotted against [S]. Data fitting against the Michaelis-Menten equation V = Vmax · [S]/(KM + [S]) or the simplified equation V = kcat[E][S]/KM (when KM >> [S]) gave the kinetic constants kcat, KM, and/or kcat/KM.

DNA Constructs and Cell Transfection

The coding sequences of BTF3L4, phosphoglucomutase (PGM1) and thioredoxin-like protein 1 (TXNL1) proteins were amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the cDNA pool of HEK293T cells with the introduction of EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. The DNA primers used for PCR amplification of the BTF3L4 gene were 5’-CGCGAATTCAGCATGAATCAAGAAAAGTTAGCC-3’ and 5’-CCGGGATCCGTTAGCTTCATTCTTTGATGC-3’. The primers used for the PGM1 gene were 5’-CGCGAATTCGCGATGGTGAAGATCGTGACAGTTAAG-3’ and 5’-CGCGGATCCGGTGATGACAGTGGGTGC-3’. The primers used for the TXNL1 gene were 5'-GAGCGGCCGCCATGGTGGGGGTGAAG-3’ and 5'-CGCGCGGATCCGTGGCTTTCTCCTTTTTTGC-3’. The PCR products were cloned into the p3xFLAG-CMV-14 vector (Sigma), resulting in the addition of a C-terminal 3xFlag tag. The final constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. The plasmids for transfection were isolated from E. coli using PureLink™ HiPure Plasmid Filter Purification Kit and PureLink™ HiPure Precipitator Module (Invitrogen).

HEK293T cells were grown in a humidified environment at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in low glucose DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) unless otherwise stated. One day prior to transfection, the cells were seeded with a density of 2 × 106 cells per 10-cm petri dish containing 10 mL of media. Immediately before transfection, 10 µg of the appropriate plasmid DNA (p3xFLAG-CMV-14-BTF3L4, p3xFLAG-CMV-14-PGM1, or p3xFLAG-CMV-14-TXNL1) was added to 1 mL of serum-free DMEM, to which 25 µL of Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, 301305) was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The cell media was then changed and the transfection mixture was added in a dropwise fashion.

Initiator Methionine Release Assay

This assay was a modification of a previously described procedure (28, 29). At 19.5 h post-transfection, the cells were treated for 4.5 h with either vehicle (DMSO), MetAP1 inhibitor IV-43 (30) (10 µM), MetAP2 inhibitor TNP-470 (100 nM), or both in 4 mL of methionine-free DMEM supplemented with 4.5 g/L glucose and sodium pyruvate (Mediatech) and 10% dialyzed FBS (Gibco). For the final 4 h of treatment, the cells were incubated with 0.2 mCi of [35S]-methionine (PerkinElmer, NEG709A). The media was removed by aspiration and the cells were resuspended in 5 mL of ice cold PBS, collected by centrifugation at 225 × g, and resuspended using a Pasteur pipet in 1 mL of ice cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.0) containing 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11872580001). Following a 10 min incubation (at 4 °C), the cell lysate was centrifuged at ∼16,000 × g for 20 min (4 °C), and the cleared supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube containing 30 µL of anti-Flag conjugated agarose resin (Sigma, A2220) that had been equilibrated by washing with RIPA buffer (3 × 1 mL). After incubation for 1.5 h on a rotating wheel (4 °C), the resin was collected by centrifugation at 500 × g for 30 s (4 °C) and washed five times with 0.9 mL of ice cold RIPA buffer (by inverting the tube 15 times between centrifugation steps). Finally, the resin was washed twice with 0.9 mL of ice cold MetAP reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 100 µM CoCl2, pH 7.5) before being resuspended in 250 µL of MetAP reaction buffer and split into two equal aliquots. Each aliquot was centrifuged at 500 × g and the supernatant was aspirated. The supernatant from one aliquot was discarded (the “no enzyme” tube) and 50 µL of MetAP reaction buffer was added to the resin. The supernatant from the other aliquot (the “enzyme reaction tube”) was set aside as the “wash” sample and recombinant MetAP1 and MetAP2 (5 µM each) were added to the resin suspended in 50 µL of MetAP reaction buffer. After incubation overnight (∼16 h) at room temperature, 75 µL of MetAP reaction buffer was added to each tube, followed by pelleting the resin and transferring the supernatant to a fresh tube. The 35S content of each sample (including the “wash” sample) was determined by mixing with 1 mL of scintillation fluid (PerkinElmer, 1200-439) and scintillation counting on a 1450 MicroBeta apparatus (Wallac). The percentage of [35S]-methionine release was calculated from the ratio of counts in the reaction buffer to the sum of these counts and the counts from the corresponding resin sample.

Results and Discussion

Design and Synthesis of MetAP Substrate Library

A one-bead-one-compound (OBOC) MetAP substrate library in the form of NH2-MX1X2X3X4X5LNBBR-Dde-resin [where B is β-alanine and X1–X5 are 2-aminobutyrate (Abu or U) and norleucine (Nle or M), which were used as Cys and Met surrogates, respectively, or any of 16 proteinogenic amino acids except for Arg, Cys, Lys, and Met] was synthesized on PEGA resin (0.4 mmol/g, 150–300 µm in diameter when swollen in water) (Scheme 1). A methionine was placed at the N-termini of all sequences because it is already well established that all MetAPs have a stringent requirement of Met as the P1 residue (21, 31). Arg, Lys, Cys, and Met were excluded (or replaced) from the random region because they would interfere with the screening procedure (vide infra). The invariant sequence LNBBR was added to facilitate MALDI MS analysis, by providing a fixed positive charge (Arg) and shifting the mass of all peptides to >500 (to avoid overlap with MALDI matrix signals). The peptides were covalently linked to the PEGA resin via a Dde linker, which permits facile peptide release by treatment with hydrazine prior to MS analysis. To construct the Dde linker, the free amino group on PEGA resin was first acylated with glutaric anhydride and the resulting carboxylic acid (1) was activated with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and condensed with 5,5-dimethylcyclohexane-1,3-dione to give enol 2 (32). Subsequent reaction of enol 2 with excess 1,5-diaminopentane provided the desired Dde linker 3 containing a free amine as the anchor for peptide synthesis. After the addition of the LNBBR sequence using standard Fmoc/HBTU chemistry, the random region was synthesized via the split-and-pool method (33, 34). After the addition of the last random residue (X1), the library was split into three sub-libraries. Sub-libraries I and II contained Ser and Thr as the X1 residue, respectively, whereas in sub-library III, the X1 residue represented an equimolar mixture of the other 16 amino acids. The theoretical diversity of the library is 185 or 1.9 × 106.

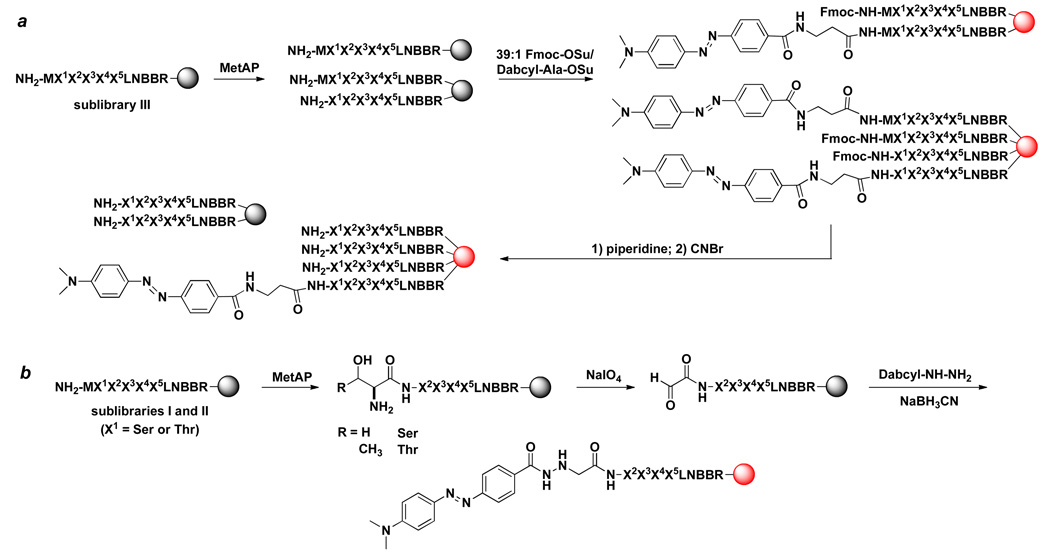

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of MetAP Substrate Librarya

aReagents and Conditions: (a) glutaric anhydride (3 equiv), DIPEA, CH2Cl2; (b) 5,5-dimethylcyclohexane-1,3-dione (4 equiv), EDC (2 equiv), DMAP (2 equiv), CH2Cl2; (c) NH2-(CH2)5-NH2 (20 equiv), CH2Cl2; (d) solid-phase peptide synthesis using Fmoc chemistry, split-and-pool synthesis at random positions, and deprotection; (e) 1.5% NH2NH2 in THF/H2O (1:1).

MetAP Library Screening

Two different methods were devised to screen the MetAP substrate library. Method A (Scheme 2a) was designed for sub-library III, which was subjected to limited MetAP reaction, so that only those beads that carried the most efficient substrates of MetAP would undergo partial cleavage of the N-terminal methionine (usually a few percent), while the vast majority of beads (which displayed poorer substrates or inactive peptides) would have little or no reaction. The library was then treated with a 39:1 (mol/mol) mixture of Fmoc-OSu and Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu, a red dye molecule. This resulted in the N-terminal acylation (or carbamoylation) of all library peptides (both MetAP reaction products and unreacted substrates) and all of the library beads became red colored (due to attachment of the Dabcyl moiety). Next, the library was treated with piperidine to remove the N-terminal Fmoc group, followed by CNBr to cleave any N-terminal methionine. For beads/peptides that did not undergo any MetAP reaction, CNBr would remove the N-terminal methionine, along with the Dabcyl group, rendering these beads colorless. On the other hand, any MetAP reaction products would not be affected by the CNBr treatment because they no longer contained any methionine in their sequences. Thus, those beads that had undergone significant MetAP reaction (positive beads) would retain the Dabcyl group and remain red colored. The positive beads were manually removed from the library using a micropipette and their peptide sequences were determined by PED-MS (27). It is worth noting that the use of 39:1 Fmoc-OSu/Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu was critical for successful library screening, as it ensured that there were sufficient amounts of peptides with free N-termini (after Fmoc removal) for PED-MS analysis. It also improved the color contrast between positive and negative beads. When only Dabcyl- β-Ala-OSu was used for N-terminal acylation, all of the library beads retained significant red color after the CNBr treatment, because methionine removal by CNBr was not quantitative.

Scheme 2.

Two Methods for Library Screening against MetAP

The above method was less effective for sub-libraries I and II (which contained Ser and Thr at the P1’ position, respectively) because CNBr cleavage of methionine is inefficient when Ser or Thr is next to methionine (35). The β-hydroxyl group of Ser (or Thr) can intramolecularly react with the five-membered-ring intermediate, resulting in the conversion of the methionine into a homoserine instead of peptide bond cleavage. We therefore developed an alternative approach (method B) for those two sub-libraries (Scheme 2b). Enzymatic cleavage of the N-terminal methionine from the library peptides generated an N-terminal Ser or Thr, which was selectively oxidized by sodium periodate into a glyoxyl group. The newly formed aldehyde group was then selectively conjugated with Dabcyl-hydrazide and reduced with NaBH3CN. Again, the resulting positive (red colored) beads were readily identified from the library and sequenced by the PED-MS method.

Substrate Specificity of E. coli MetAP1

A total of 105 mg of sub-library III (∼3.9 × 105 beads) was screened against E. coli MetAP1 in five separate experiments (25 or 25 mg of resin each). The most colored beads were isolated and sequenced by PED-MS to give 236 complete sequences, which should represent the most efficient substrates of E. coli MetAP1 (Table 1). Similar sequences were selected from each screening experiment, demonstrating the reproducibility of the screening method. E. coli MetAP1 has the most stringent specificity at the P1’ position, with Ala being the most preferred amino acid (in 84% of all selected sequences), followed by glycine (10%) and 2-aminobutyrate (6%) (Figure 1a). At the P2’ position, E. coli MetAP1 tolerates a wide variety of amino acids, but with preference for hydrophilic residues (Glu, Asp, Asn, Gln, Ser, and Thr) or small residues such as Ala and Abu. A few of the selected peptides also contained a Phe at the P2’ position. Interestingly, out of the 236 selected peptides, none contained a proline, histidine, or tryptophan at this position. The enzyme also has broad specificity at the P3’ position, where hydrophobic residues were frequently selected, whereas acidic residues (especially Asp), Gly, His, and Trp were underrepresented. There appears to be a negative correlation between the P2’ and P3’ positions with respect to acidic amino acids. When the P2’ residue was acidic, the P3’ residue was almost always hydrophobic; and vice versa, when Asp or Glu was present at the P3’ position, the P2’ residue was typically hydrophobic (Table 1). None of the most preferred substrates contained acidic residues at both P2’ and P3’ positions. No obvious selectivity was observed at the P4’ or P5’ position. Screening of sub-libraries I and II (9 mg each) by method B revealed a similar specificity profile at the P3’–P5’ positions, although Ala and acidic residues (Asp and Glu) were more frequently selected at the P2’ position when Ser or Thr was the P1’ residue (Figure 1b and Table S1 in Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Most Preferred Substrates of E. coli MetAP1 Selected from Sub-library III (236 Total)a

| AAADV | AEUEI | ANVIN | AUPSE |

| AADEI | AEUEG | ANVHI | AUSFG |

| AAELI | AEVMH | ANVIG | AUTAN |

| AAFNT | AEVMA | ANYGA | AUTNP |

| AAFTQ | AEVMD | ANYQG | AUUNH |

| AAIST | AEVNI | AQAGE | AUUFG |

| AALHQ | AEVTE | AQFAG | AUUEF |

| AAMEP | AEVIS | AQFGP | AUVHT |

| AANDI | AEVDI | AQGUI | AVEGY |

| AANN I | AEYPV | AQLVG | AVGFP |

| AAPEI | AEYGA | AQNVU | AVNHI |

| AATSI | AFAEG | AQNIP | AVTHT |

| AATYP | AFDND | AQNFT | AVTEU |

| AATNT | AFEGP | AQNFP | AVUAD |

| AAUIS | AFNUG | AQQUH | AVUDS |

| AAUHI | AFNQS | AQQUD | AYNQQ |

| AAUMD | AFPGI | AQSAN | AYNNU |

| AAASU | AFPNT | AQSMI | AYSET |

| ADAAL | AFPSP | AQSMI | AYSSG |

| ADAFE | AFSHS | AQSVQ | AYVSL |

| ADFEU | AFSTH | AQSNI | GAEIE |

| ADLMP | AFSDI | AQSTY | GAMHE |

| ADMDI | AFSNS | AQSSA | GAUEY |

| ADPEM | AFSQT | AQSHU | GDFDF |

| ADSLG | AFTMP | AQTEM | GDMLP |

| ADSAF | AFVGP | AQTAS | GDVSL |

| ADTQF | AGGPD | AQVUT | GEUID |

| ADTIN | AIDED | AQVGI | GFADQ |

| ADTAI | ALAGE | ASAES | GFAGE |

| ADUGA | ALUVU | ASFUU | GFIDN |

| ADUAA | AMAEQ | ASINE | GFSEI |

| ADWDM | AMANI | ASLEV | GFSQE |

| ADYNI | AMEVD | ASLNS | GFSSQ |

| AEAFD | AMNSG | ASMHQ | GLAHG |

| AEANY | AMUAP | ASNVG | GLTDT |

| AEFEM | ANADF | ASNIT | GMNEP |

| AEFHE | ANAEQ | ASSMN | GMUEE |

| AEISI | ANAEH | ASTHE | GMUTE |

| AEIED | ANFUT | ASUTL | GNFEE |

| AEIEIb | ANISI | ASVSM | GNLME |

| AEIIG | ANIDE | ASVHV | GSLES |

| AELID | ANLNV | ASVVS | GSTLE |

| AELFA | ANLEQ | ASYSU | GSUEF |

| AELEE | ANMIG | ATFTE | GUEEF |

| AELVU | ANMTA | ATIEE | UDYGD |

| AEMEI | ANMDF | ATMNS | UEFEE |

| AEMSN | ANNHE | ATQPI | UEMFE |

| AEMNQ | ANSQY | ATUYT | UETIN |

| AEMEW | ANTQL | ATVAU | UFSEV |

| AENYP | ANTVG | AUADF | UFUET |

| AEPIV | ANTEA | AUEYD | UNQIH |

| AESTF | ANTYT | AUFGA | UNVHN |

| AETLH | ANTVA | AUGEF | UNVDM |

| AETTY | ANUSI | AUIPS | UQGEF |

| AETID | ANUID | AUIGP | UQUNG |

| AEUVG | ANUEM | AUIAP | USMED |

| AEUGG | ANUQY | AUPAI | USUIT |

| AEUEH | ANVED | AUPSN | UTDLE |

| AEUQF | ANVIY | AUPSE | UUEID |

Sequences were obtained from five screening experiments performed at 75–100 nM E. coli MetAP1. U, α-L-aminobutyric acid; M, norleucine.

Peptide selected for further kinetic analysis.

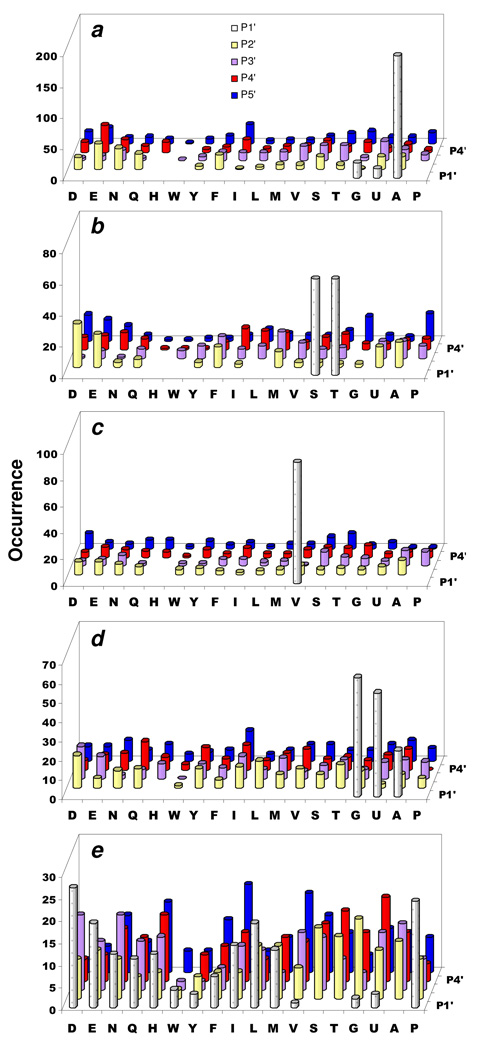

Figure 1.

Substrate specificity of E. coli MetAP1. (a) Most preferred substrates selected from sub-library III (total 236 sequences); (b) most preferred substrates from sub-library I and II (total 124 sequences); (c) Val-containing sequences (at P1’ position) derived from medium colored beads in sub-library III (total 92 sequences); (d) Ala-, Abu-, and Gly-containing sequences (at P1’ position) derived from medium colored beads in sub-library III (total 140 sequences); and (e) sequences derived from colorless beads in sub-library III (total 169 sequences). Displayed are the amino acids identified at each position (P1’ to P5’). Occurrence on the y axis represents the number of selected sequences that contained a particular amino acid at a certain position.

To identify the less efficient substrates and MetAP-resistant sequences, sub-library III (40 mg) was treated exhaustively with a high concentration of E. coli MetAP1 (1.0 µM) for an extended period of time (overnight). In addition to intensely colored beads, this screening experiment also produced many medium and lightly colored beads (∼15% of all library beads), which should represent the less efficient substrates of E. coli MetAP1. We randomly selected some of the medium colored beads for sequence analysis and obtained 232 complete sequences (Table S2 in Supporting Information). Our results showed that 40% of these less efficient substrates contained a Val as the P1’ residue, while the rest of peptides had Gly (27%), Abu (23%), and Ala (10%) at this position. When the subset of sequences that contained Val as the P1’ residue were analyzed, the specificity profile at the P2’–P5’ positions was essentially identical to that observed for the most efficient substrates (Figure 1c). Similar analysis of the other subset of sequences (which contained Gly, Abu, or Ala as the P1’ residue) showed that they usually contained less favorable amino acids at the P2’ (e.g., Gly, Ile, Leu, and Pro) and/or P3’ positions (e.g., Asp, Glu, and His) (Figure 1d). Sequence analysis of 171 randomly selected colorless beads from the library showed that most of the MetAP-resistant peptides contained amino acids with large side chains as the P1’ residue, while none of them had Ala at the P1’ position (Figure 1e and Table S3 in Supporting Information). Only six of the peptides contained Gly (MGDVFQ, MGPTET), Abu (MUHINS, MUPETF, MUILVE) or Val (MVLFHH) at the P1’ position. These peptides either contained a disfavored residue at the P2’ position (Pro or His) or were very hydrophobic (MUILVE and MVLFHH), making the beads poorly swelled in aqueous solution and thus poorly accessible to the enzyme during library screening. As expected from the large number of colorless beads (∼75% of all beads), there was no obvious “selectivity” at the P2’-P5’ positions. These data indicate that all N-methionyl peptides containing a small P1’ residue (Ala, Gly, Abu, Ser, Thr, and Val) are accepted as E. coli MetAP1 substrates, albeit with different catalytic efficiencies.

Substrate Specificity of Human MetAP1

Human MetAP1 was similarly screened against sub-libraries I–III to identify peptide sequences that are most preferred or less preferred by the enzyme, and resistant to the enzyme. The most intensely colored beads were selected from sub-libraries III (60 mg) and I (9 mg) and sequenced to give 128 and 74 unambiguous sequences, respectively (Table S4 and Table S5). Similar sequences were selected from the two sub-libraries (Figure 2a, b). In general, human MetAP1 has a similar specificity profile to E. coli MetAP1, but also has some unique features. Like the E. coli enzyme, human MetAP1 prefers Ala at the P1’ position, but this preference is stronger than that of E. coli MetAP1 (124 out of the 128 best substrates had Ala as the P1’ residue). Only four peptides contained Gly (3 peptides) or Abu (1 peptide) as the P1’ residue. The underrepresentation of Abu at this position suggests that amino acids with larger (than a methyl group) side chains are poorly tolerated by the human MetAP1 active site. This notion is further supported by the data from sub-library II (which contained Thr as the P1’ residue) (Figure 2c and Table S6 in Supporting Information). Screening of sub-library II against human MetAP1 only produced lightly colored beads, despite the use of a higher enzyme concentration (800 nM) and longer reaction time (2 h), suggesting that any peptide containing a Thr at the P1’ position is a relatively poor substrate of human MetAP1. Other features shared with the E. coli enzyme include the absence (or underrepresentation) of Pro at the P2’ position and His and Trp at both P2’ and P3’ positions among the most active substrates. The most striking difference between the E. coli and human MetAP1 lies in their different tolerance to acidic residues. While E. coli MetAP1 prefers Asp and Glu at P2’, P4’, and P5’ positions (Figure 1), the human enzyme strongly disfavors acidic residues at all positions. Out of the 245 most preferred substrates selected from sub-libraries I, II, and III, only one sequence [MA(Nle)DWE] contained acidic residues. Another difference is that while E. coli MetAP1 disfavors Gly at P2’ and P3’ positions, the human enzyme has no such discrimination.

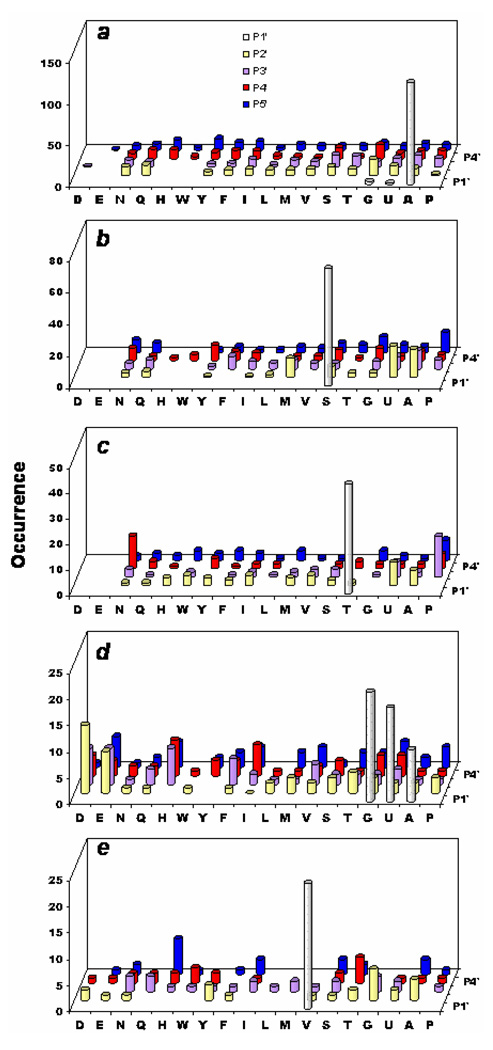

Figure 2.

Substrate specificity of human MetAP1. (a) Most preferred substrates selected from sub-library III (total 128 sequences); (b) most preferred substrates from sub-library I (total 74 sequences); (c) most preferred substrates selected from sub-library II (total 43 sequences); (d) Ala-, Abu-, and Gly-containing sequences (at P1’ position) derived from medium colored beads in sub-library III (total 50 sequences); and (e) Val-containing sequences (at P1’ position) derived from medium colored beads in sub-library III (total 24 sequences). Displayed are the amino acids identified at each position (P1’ to P5’). Occurrence on the y axis represents the number of selected sequences that contained a particular amino acid at a certain position.

The less optimal substrates and inactive peptides were identified by treating sub-library III (12 mg) with a high concentration of human MetAP1 (2.7 µM) for 24 h and randomly selecting a fraction of the medium colored and colorless beads for sequence analysis. The less optimal substrates contained Val (33%), Gly (28%), Abu (24%) and Ala (15%) as the P1’ residue (Table S7 in Supporting Information). Out of the 48 Gly-, Abu-, and Ala-containing (at P1’ position) peptides, 35 contained at least one acidic residue, often at the P2’ and/or P3’ position, while three other peptides had Pro as the P2’ residue (Figure 2d). The Val-containing peptides (at position P1’) contained no Pro at the P2’ position and much fewer acidic residues in their sequences (Figure 2e). None of the MetAP1-resistant peptides contained Ala or Gly at the P1’ position, while two peptides had Abu or Val as the P1’ residue (Figure S1 in Supporting Information). These data provide further support for our conclusion that a larger P1’ residue (e.g., Val and Thr), a Pro at the P2’ position, and/or acidic residues at P2’ to P5’ positions can decrease the catalytic activity toward human MetAP1. They also suggest that human MetAP1, like the E. coli enzyme, will accept essentially all N-methionyl peptides containing Ala, Gly, Abu, Ser, Thr, or Val at the P1’ position as substrates, although the Thr- and Val-containing peptides are generally inefficient substrates.

Substrate Specificity of Human MetAP2

Sub-libraries I (4.3 mg), II (4.3 mg), and III (80 mg) were screened against human MetAP2 and the most intensely colored beads were sequenced to give 96, 65, and 632 complete sequences, respectively (Tables S8–10 in Supporting Information). In addition, 88 medium colored beads were isolated from sub-library III and sequenced (Table S11 in Supporting Information). In general, human MetAP2 has a very similar specificity profile to human MetAP1 (Figure 3). For example, both human MetAP1 and MetAP2 disfavor Pro at the P2’ position, Trp at P2’ and P3’ positions, and acidic residues at positions P2’ to P5’. The main difference between the two enzymes is their specificity at the P1’ position. While only one out of the 128 most preferred substrates of human MetAP1 contained an Abu as the P1’ residue, MetAP2 selected Abu with the second highest frequency (122 out of 632 sequences), more frequently than Gly (90 sequences). Moreover, 19 of the most preferred substrates had a Val as the P1’ residue. This suggests that the S1’ site of human MetAP2 is more capable of accommodating amino acids with larger side chains than does MetAP1. This notion is also supported by our data on sub-library II. We found that treatment of sub-library II with 250 nM human MetAP2 generated intensely colored beads in 2 h, while treatment with 800 nM human MetAP1 for 2 h only produced lightly colored beads. We noted that unlike E. coli and human MetAP1, MetAP2 selected a significant number of His at the P2’ and P3’ positions. The underlying reason is not yet clear.

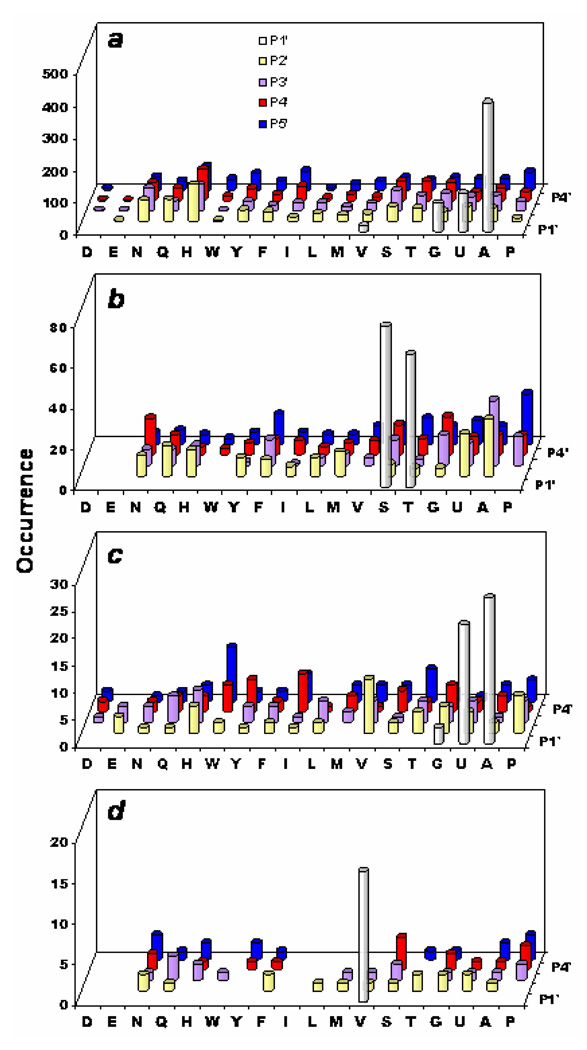

Figure 3.

Substrate specificity of human MetAP2. (a) Most preferred substrates selected from sub-library III (total 632 sequences); (b) most preferred substrates from sub-libraries I and II (total 144 sequences); (c) Ala-, Abu-, and Gly-containing sequences (at P1’ position) derived from medium colored beads in sub-library III (total 52 sequences); and (d) Val-containing sequences (at P1’ position) derived from medium colored beads in sub-library III (total 16 sequences). Displayed are the amino acids identified at each position (P1’ to P5’). Occurrence on the y axis represents the number of selected sequences that contained a particular amino acid at a certain position.

Kinetic Properties of Selected MetAP Substrates

Fifteen peptides were synthesized individually on a larger scale, purified by HPLC, and assayed against the three MetAPs to confirm the screening results as well as provide specificity data on amino acid residues excluded from the library (i.e., Arg and Lys) (Table 2, entries 1–15). Peptides 1 and 2 are two of the most preferred substrates of E. coli MetAP1, selected from sub-libraries III and I, respectively (Table 1 and Table S1). Peptide 12 is a preferred substrate of human MetAP2 selected from sub-library III (Table S8). The rest of the peptides are variants of peptides 1 and 12, designed to test the effect of the P1’–P3’ residues on MetAP activity. A Tyr was added to the C-terminus of each peptide to facilitate their concentration determination. Since most of the peptides did not reach saturation at the highest concentration tested (1.0 mM), only their kcat/KM values are used for comparison.

Table 2.

Kinetic Constants of E. coli and Human MetAPs against Selected Peptidesa

| Entry No. |

Peptide |

kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) |

Rel. Activity MetAP2/1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli MetAP1 | Human MetAP1 | Human MetAP2 | |||

| 1 | MAEIEIYb | 14000 ± 3900 | 1700 ± 160 | 1040 ± 50 | 0.63 |

| 2 | MSDFIGYb | 28000 ± 1100 | ND | ND | ND |

| 3 | MGEIEIY | 4100 ± 120 | 180 ± 8 | 660 ± 20 | 3.6 |

| 4 | MPEIEIY | 3000 ± 1490 | 160 ± 8 | 140 ± 60 | 0.88 |

| 5 | MTEIEIY | 1500 ± 50 | 29 ± 2 | 460 ± 60 | 16 |

| 6 | MVEIEIY | 380 ± 110 | NA | 450 ± 180 | >200 |

| 7 | MARIEIY | 18900 ± 1300 | 6600 ± 600 | 23300 ± 1700 | 3.5 |

| 8 | MAGIEIY | 13500 ± 7600 | ND | ND | ND |

| 9 | MAPIEIY | NA | 1300 ± 20 | 540 ± 25 | 0.43 |

| 10 | MAHIEIY | 14500 ± 550 | 3580 ± 350 | 5000 ± 3800 | 1.4 |

| 11 | MVKIEIY | ND | ∼7 | 860 ± 210 | 116 |

| 12 | MAHAIHYb | ND | 41000 ± 18000 | 36000 ± 1900 | 0.88 |

| 13 | MAGAIHY | ND | 10000 ± 340 | 37000 ± 6200 | 3.7 |

| 14 | MAWIEIY | ND | 9600 ± 350 | 4900 ± 750 | 0.51 |

| 15 | MAEWEIY | ND | 5300 ± 90 | 2160 ± 800 | 0.41 |

| 16 | MVHQVLYc | ND | 64 ± 5 | 4000 ± 240 | 63 |

| 17 | MVNPTVYc | ND | 13 ± 2 | 2600 ± 60 | 200 |

| 18 | MVLSPAYc | ND | 15 ± 1 | 2600 ± 1000 | 175 |

| 19 | MVGVKPYc | ND | 28 ± 1 | 2070 ± 280 | 74 |

| 20 | MVAAAAYc | ND | 130 ± 6 | 10000 ± 1000 | 79 |

All peptides contained a free N-terminus and a C-terminal amide. NA, no detectable activity; ND, not determined.

Peptides selected from the combinatorial library.

Peptides derived from human proteins.

As expected, peptides 1 and 2 were highly active toward the E. coli enzyme, having kcat/KM values of 14000 and 28000 M−1 s−1, respectively (Table 2). Replacement of the Ala at the P1’ position with Gly, Pro, Thr, and Val decreased the activity by 3.4-, 4.7-, 9.3-, and 44-fold, respectively. This is largely consistent with the screening results, except for the proline-containing peptide. Previous studies have also shown that peptides containing Pro as the P1’ residue are efficiently hydrolyzed by MetAPs (17–25). Thus, the absence of Pro from the P1’ position among the selected substrates were likely caused by the bias of the screening procedure (method A). Proline, which bears a secondary amine, is significantly less reactive to activated esters such as Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu than the other 19 proteinogenic amino acids (36). Presumably, MetAP reaction products that contained an N-terminal proline were not efficiently labeled by Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu and became false negatives. Replacement of the P2’ residue (Glu) with an arginine, which was excluded from the library for technical reasons, slightly increased the catalytic activity (by 1.3-fold). This suggests that the frequent selection of acidic residues at the P2’ position was not due to the presence of favorable charge-charge interactions; the E. coli enzyme simply prefers a hydrophilic residue at this position. Indeed, other neutral, hydrophilic residues such as Asn, Gln, and Ser were also frequently selected at this position (Figure 1). Consistent with the absence of Pro from the P2’ position among the most preferred substrates, peptide 9 (MAPIEIY) had an activity that was too low to be reliably determined by the HPLC assay. A surprising finding was that peptide 10, which contains a His at the P2’ position, had excellent activity (kcat/KM = 14500 M−1 s−1), even though His was not at all selected at this position (Figure 1). Careful kinetic analysis showed that at higher concentrations (>100 µM), peptide 10 inhibited the MetAP activity (data not shown). During HPLC analysis of the MetAP reaction mixture, we observed that peptide 10 formed a complex with the Co2+ ion (used in MetAP assays). The peptide-metal complex had a different retention time from the free peptide and disappeared when a lower concentration of Co2+ ion was used in the assay buffer. Presumably, during library screening, the His-containing peptides inhibited the MetAP enzymes by binding to their active-site metal ion(s). Inhibition of MetAP by Met-X-His peptides had also been reported by other investigators (16).

Kinetic assays of human MetAP1 and MetAP2 against the above peptides also confirmed their specificity profiles revealed by library screening. Indeed, both human enzymes disfavor acidic residues. Replacement of a Glu at the P2’ position by either Arg or His increased the catalytic activity by 2–22-fold (Table 2, compare peptides 1, 7, and 10). Likewise, a Glu at the P4’ position reduced the activity of both enzymes by 7–12-fold (compare peptides 10 and 12). Human MetAP2 is more tolerant than MetAP1 to larger P1’ residues. While all of the peptides containing Ala, Gly, or Pro at the P1’ position had similar activities toward the two enzymes (MetAP2/1 ratio between 0.43 and 3.7), peptides 6 and 11, which contain a Val at the P1’ position, were two orders of magnitude more active toward MetAP2 than MetAP1. MetAP2 also had a 16-fold higher activity than MetAP1 toward a Thr-containing peptide (peptide 5). To test whether this is a general property of MetAP2, we synthesized five additional Met-Val peptides, derived from the N-terminal sequences of human proteins sulfurtransferase, cyclophilin A, hemoglobin α chain, thioredoxin-like protein 1 (TXNL1), and attractin, which are known to undergo N-terminal methionine removal in vivo (Table 2, peptides 16–20) (37). All five peptides had kcat/KM values in the range of 2000–10000 M−1 s−1 toward MetAP2, but were only poorly active toward human MetAP1 (74–200-fold lower activity). Our data suggest that these five proteins, and likely all Met-Val- and Met-Thr-containing proteins in human, are mainly processed by MetAP2 in vivo. Previous X-ray crystal structural studies have shown that human MetAP1 has a narrower active-site cleft than MetAP2 (by ∼1 Å) and the reduced size restricts the access of fumagillin and related compounds to the active site of MetAP1 (26). Similarly, the smaller active site of MetAP1 would sterically clash with the larger side chains of Val and Thr at the P1’ position. Finally, we tested two Trp-containing peptides (Table 2, peptides 14 and 15) to determine the effect of Trp on MetAP activities. Surprisingly, although none of the enzymes selected Trp among their most preferred substrates (Figures 1–3), both peptides (which contain a Trp at the P2’ and P3’ positions, respectively) were efficient substrates of human MetAP1 and MetAP2. A possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that beads displaying hydrophobic Trp-containing peptides swelled poorly in the aqueous screening buffer, rendering the peptides on these beads poorly accessible to the MetAP enzymes.

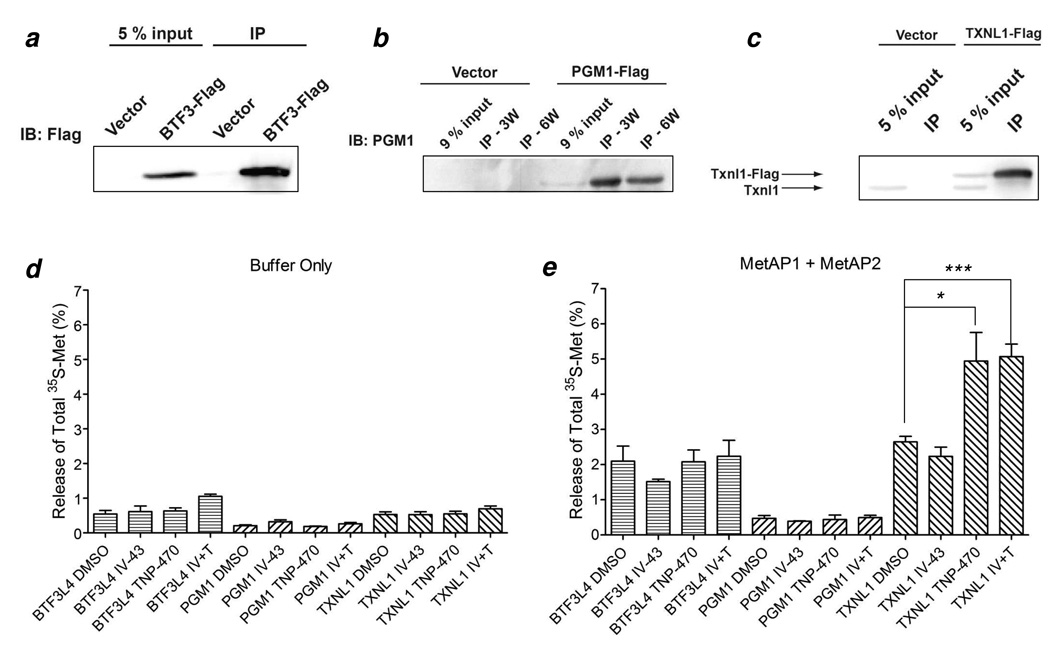

In Vivo Validation of MetAP1 and MetAP2 Substrate Specificity

To validate the in vitro substrate specificity data, we examined the N-terminal Met removal from phosphoglucomutase 1 (PGM1) and TXNL1 in vivo. PGM1 and TXNL1 contain N-terminal sequences of MVKIVT and MVGVKP, respectively, and are expected to be specific substrates of MetAP2. The protein BTF3L4, which has an N-terminal sequence of MNQEKL and is not expected to undergo N-terminal Met removal, was used as a negative control. Human embryonic kidney epithelial cell line HEK293T overexpressing C-terminally Flag-tagged PGM1, TXNL1, or BTF3L4 proteins were treated with IV-43 [a specific MetAP1 inhibitor (38)] and/or TNP-470 [a specific MetAP2 inhibitor (13)] and then pulsed with [35S]Met to label any newly synthesized proteins. The putative substrate proteins (and control) were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with antibodies against the Flag tag. The partially purified proteins were then treated with recombinant MetAP1 and MetAP2 in vitro to cleave any retained N-terminal [35S]Met residue, which was caused by inhibition of the cellular MetAPs. Treatment of the cells expressing TXNL1 with either TNP-470 alone or TNP-470 and IV-43 in combination, but not IV-43 alone, resulted in a two-fold increase in the N-terminal Met retention over the DMSO control (Figure 4). No significant increase in Met retention was observed for cells expressing BTF3L4 or PGM1. These results demonstrate that TXNL1 is indeed a specific substrate of MetAP2. The result with PGM1 was unexpected and may be caused by one or both of the following factors. Inspection of the structure of PGM1 shows that the retained Met would be buried in the folded protein and thus inaccessible to MetAP action (39). Alternatively, the N-terminal Met might be N-acetylated upon forced retention in cells and protected against MetAP2 in vitro. In this regard, treatment of human and mouse cells with TNP-470 resulted in the retention and acetylation of the N-terminal Met of cyclophilin A, a well-established MetAP2-specific substrate (40).

Figure 4.

Retention of the initiator methionine of TXNL1 caused by inhibition of MetAP2 by TNP-470. (a) Immunoblotting (IB) of immunoprecipitated (IP) C-terminal 3xFlag-tagged BTF3L4 protein from HEK293T cell lysate; (b) Immunoblotting of immunoprecipitated C-terminal 3xFlag-tagged PGM1 protein from HEK293T cell lysate (3W, three times washes with RIPA buffer; 6W, six times washes with RIPA buffer); (c) Immunoblotting of immunoprecipitated C-terminal 3xFlag-tagged TXNL1 protein from HEK293T cell lysate; (d) and (e) Immunoprecipitated C-terminal 3xFlag-tagged BTF3L4, PGM1 and TXNL1 were aliquoted for [35S]-methionine scintillation counting after incubation with MetAP reaction buffer (d) or after in vitro processing by both MetAP1 and MetAP2 (e). IV-43 or IV (10 µM), TNP-470 or T (100 nM) or both were added for the last 4.5 h. The error bars are standard errors from two (BTF3L4 and PGM1 in (d)), three (TXNL1 in (d) and BTF3L4 and PGM1 in (e)) or five (TXNL1 in (e)) independent experiments. N-Terminally methionine unprocessed BTF3L4, PGM1 and TXNL1 have 3, 12 and 8 methionine residues per molecule, respectively. * p=0.02; *** p=0.0003.

Corroboration with Literature Data

Previous studies have led to the conclusion that both bacterial and eukaryotic MetAPs prefer small amino acids (e.g., Ala, Gly, Ser, Pro, Cys, Thr, and Val) as the P1’ residue (17–25). Our results confirmed these earlier findings. Several studies demonstrated the importance of residues at positions P2’ and beyond for catalytic activity (20, 21). The only systematic study of MetAP substrate specificity was carried out by Frottin et al. (25), who synthesized and assayed ∼120 short peptides against E. coli MetAP1 and P. furiosus MetAP2. Their data suggest that N-terminal methionine removal from proteins in vivo is dictated by the substrate specificity of MetAP(s). Our data on E. coli MetAP1 are largely consistent with the results of Frottin et al, but with one key difference. Frottin et al. reported that E. coli MetAP1 had poor activity against peptides containing acidic residues at P2’–P4’ positions. In contrast, our library screening and kinetic analysis of individually synthesized peptides both showed that the E. coli enzyme prefers acidic residues at P2’, P4’, and P5’ positions. This discrepancy is likely due to the fact that Frottin et al. employed very short peptides containing free C-termini (primarily tri- and tetrapeptides), which generally had poor activities toward the E. coli enzyme (kcat/KM ∼ 102–103 M−1 s−1). As described previously, our screening data revealed a negative correlation between the P2’ and P3’ positions with regard to acidic residues (i.e., the enzyme disfavors the presence of negative charges at both positions). Presumably, the negatively charged C-terminus of the peptides used in the Frottin work interfered with the binding of acidic peptides to the enzyme active site.

Proteomics analyses of TNP-470 treated cells have identified several mammalian proteins as MetAP2-specific substrates, including bovine cyclophilin A (N-terminal sequence MVNPTV) (41) and glyeraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (MVKVGV) (41) and human thioredoxin (MVKQI) (40), SH3 binding glutamic acid rich-like protein (MVIRV) (40), and elongation factor-2 (MVNFT) (40). In vitro kinetic assays of the N-terminal peptides of these proteins confirmed that they all have two orders of magnitude higher activity toward MetAP2 than MetAP1. Thus, together with TXNL1 identified in this work, all six MetAP2 specific substrates contain a Val as the P1’ residue, consistent with our library screening data. One known exception is human protein 14-3-3γ, which became incompletely processed when either normal or tumor epithelial cells were treated with siRNA specific for MetAP2 or MetAP1-specific inhibitor IV-43 (30, 42). The N-terminal sequence of this protein, MVDREQ, suggests that it is a poor substrate for both MetAP1 and MetAP2 (Table 2, entry 6). It is thus not surprising that an increase in retention of its N-terminal methionine was observed upon inhibition of either MetAP1 or MetAP2, suggesting that both MetAP1 and MetAP2 are necessary to completely process its N-terminal Met.

Predicted N-Terminal Met Removal Pattern in E. coli and Human Proteome

On the basis of the specificity data from the current work and in the literature (43), we make the following predictions about the N-terminal Met removal (Table 3). In E. coli, proteins containing small residues Ala, Cys, Gly, Pro, and Ser as the P1’ residue and any amino acids other than Pro at the P2’ position are expected to undergo complete Met cleavage. When the P1’ residue is any amino acid other than Ala, Cys, Gly, Pro, Ser, Thr, and Val or if the P2’ residue is Pro, the N-terminal Met is retained. When the P1’ residue is Thr or Val and the P2’ residue is not Pro, N-terminal Met cleavage is variable, depending on several factors such as the actual N-terminal sequence at P2’–P5’ positions, the level of protein expression, and the growth condition of the cell. In mammalian cells, proteins containing Ala, Cys, Gly, Pro, or Ser at the P1’ position generally undergo complete N-terminal processing, catalyzed by MetAP1, MetAP2, or both. When the P1’ residue is Thr or Val, the N-terminal Met removal is primarily catalyzed by MetAP2 and the extent of cleavage depends on the sequence at P2’–P5’ positions. When the P2’ residue is not Asp, Glu, or Pro, the N-terminal processing is expected to be complete. When Asp, Glu, or Pro is the P2’ residue, Met removal is either incomplete or does not occur. It should be noted that these rules are meant to be a general guideline and occasional exceptions have been observed.

Table 3.

Prediction of N-Terminal Met Removal in E. coli and Mammalian Cytoplasm

| N-terminal sequence | Met Removal? | Enzyme |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| <M[ACGPS][^P]a | yes | MetAP1 |

| <M[ACGPSTV]P | no | |

| <M[VT][^P] | variable | MetAP1 |

| <M[DEFHIKLMNQRWY] | no | |

| Mammalian | ||

| <M[ACGPS] | yes | MetAP1 and 2 |

| <M[VT][^DEP] | yes | MetAP2 |

| <M[VT][DEP] | variable | MetAP2 |

| <M[DEFHIKLMNQRWY] | no |

“<M” indicates that the Met is at the N-terminus of a protein; “[ACGPS]” indicates that the P1’ residue is Ala, Cys, Gly, Pro, or Ser; “[^P]” indicates that Pro is excluded from the P2’ position.

Conclusion

We have developed a novel peptide library method to systematically profile the sequence specificity of bacterial and human MetAPs. The results show that the specificity of MetAPs is largely dictated by the P1’ residue, however, the sequence at P2’–P5’ positions does have a significant effect on the extent of Met removal, especially for proteins containing less optimal P1’ residues (e.g., Thr and Val). Further, we show that the primary difference between human MetAP1 and MetAP2 is their differential tolerance for Thr and Val at the P1’ position, suggesting that MetAP2 is primarily responsible for N-terminal processing of proteins that contain N-terminal Met-Val and Met-Thr sequences. This difference in substrate specificity between human MetAP1 and MetAP2 may be ultimately responsible for the unique effects of inhibitors of MetAP2 on angiogenesis. Finally, our data have permitted us to formulate a more complete set of rules for predicting the fate of N-terminal Met of bacterial and mammalian proteins.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- Abu (U)

2-aminobutyrate

- Dabcyl-β-Ala-OSu

N-hydroxylsuccinimidyl 3-[4-(4-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoylamino]propionate

- Dabcyl-OSu

N-(4-[4’-(dimethylamino)phenylazo]benzoyloxy)succinimide

- Dde

N-1-(4,4-dimethyl-2,6-dioxocyclohexylidene)ethyl

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide

- Fmoc-OSu

N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyloxy) succinimide

- HBTU

O-benzotriazole-N,N,N',N'-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate

- MetAP

methionine aminopeptidase

- Nle (M)

norleucine

- OBOC

one-bead-one-compound

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PED-MS

partial Edman degradation-mass spectrometry

- PEGA

amino polyethylene glycol

- PGM1

phosphoglucomutase

- PITC

phenyl isothiocyanate

- TXNL1

thioredoxin-like protein 1

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM062820, CA132855, and CA078743). BN was supported by the NIH Medical Scientist Training Program Grant T32GM07309.

Supporting Information Available: Tables containing the peptides sequences selected against the three MetAP enzymes and additional figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meinnel T, Mechulam Y, Blanquet S. Methionine as translation start signal-A review of the enzymes of the pathway in Escherichia coli. Biochimie. 1993;75:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90005-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waller JP. The NH2-terminal residue of the proteins from cell-free extract of E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1963;7:483–496. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giglione C, Boularot A, Meinnel T. Protein N-terminal methionine excision. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:1455–1474. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3466-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang SP, McGary EC, Chang S. Methionine aminopeptidase gene of Escherichia coli is essential for cell growth. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:4071–4072. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.4071-4072.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Chang Y-H. Amino-terminal protein processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an essential function that requires two distinct methionine aminopeptidases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:12357–12361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller CG, Kukral AM, Miller JL, Movva NR. pepM is an essential gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:5215–5217. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5215-5217.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang W, Chai SC, Huang M, He H, Hurley TD, Ye Q. Discovery of inhibitors of Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase with the Fe(II)-form selectivity and antibacterial activity. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:6110–6120. doi: 10.1021/jm8005788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evdokimov AG, Pokross M, Walter RL, Mekel M, Barnett BL, Amburgey J, Seibel W, Soper SJ, Djung JF, Fairweather N, Diven C, Rastogi V, Grinius L, Klanke C, Siehnel R, Twinem T, Andrews R, Curnow A. Serendipitous discovery of novel bacterial methionine aminopeptidase inhibitors. Protein: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2007;66:538–546. doi: 10.1002/prot.21207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiracek J, Liboska R, Zakova L, Dygas-Holz AM, Holz RC, Zertova M, Budesinsky M. New pseudopeptide inhibitors for the type-1 methionine aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli. J. Pep. Sci. 2006;12 165-165. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Q, Huang M, Nan F-J, Ye Q. Metalloform-selective inhibition: Synthesis and structure-activity analysis of Mn(II)-form-selective inhibitors of Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:5386–5391. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith EC, Su Z, Turk BE, Chen S, Chang Y-H, Wu Z, Biemann K, Liu JO. Methionine aminopeptidase (type 2) is the common target for angiogenesis inhibitors AGM-1470 and ovalicin. Chem. Biol. 1997;4:461–471. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sin N, Meng L, Wang MQW, Wen JJ, Bornmann WG, Crews CM. The anti-angiogenic agent fumagillin covalently binds and inhibits the methionine aminopeptidase, MetAP-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6099–6103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingber D, Fujita T, Kishimoto S, Sudo K, Kanamaru T, Brem H, Folkman J. Synthetic analogs of fumagillin that inhibit angiogenesis and suppress tumor-growth. Nature. 1990;348:555–557. doi: 10.1038/348555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto T, Sudo K, Fujita T. Significant inhibition of endothelial-cell growth in tumor vasculature by an angiogenesis inhibitor, TNP-470 (AGM-1470) Anticancer Res. 1994;14:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abe J, Zhou W, Takuwa N, Taguchi J, Kurokawa K, Kumada M, Takuwa Y. A fumagillin derivative angiogenesis inhibitor, AGM-1470, inhibits activation of cyclin-dependent kinases and phosphorylation of retinoblastoma gene-product but not protein tyrosyl phosphorylation or protooncogene expression in vascular endothelial-cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3407–3412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendall RL, Bradshaw RA. Isolation and characterization of the methionine aminopeptidase from porcine liver responsible for the cotranslational processing of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:20667–20673. 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Bassat A, Bauer K, Chang SY, Myambo K, Boosman A, Chang S. Processing of the initiation methionine from proteins: Properties of the Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase and its gene structure. J. Bacteriol. 1987;169:751–757. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.751-757.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirel P-H, Schmitter J-M, Dessen P, Fayat G, Blanquet S. Extent of N-terminal methionine excision from Escherichia coli proteins is governed by the side-chain length of the penultimate amino acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:8247–8251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flinta C, Persson B, Jornvall H, von Heijne G. Sequence determinants of cytosolic N-terminal protein processing. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;154:193–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boissel J-P, Kasper TJ, Shah SC, Malone JI, Bunn HF. Amino-terminal processing of proteins - Hemoglobin south Florida, a variant with retention of initiator methionine and N-alpha-acetylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:8448–8452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang Y-H, Teicher U, Smith JA. Purification and characterization of a methionine aminopeptidase from Saccharomyces-cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:19892–19897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsunasawa S, Stewart JW, Sherman F. Amino-terminal processing of mutant forms of yeast iso-1-cytochrome-c - The specificities of methionine aminopeptidase and acetyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:5382–5391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker KW, Bradshaw RA. Yeast methionine aminopeptidase I - Alteration of substrate specificity by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13403–13409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang G, Kirkpatrick RB, Ho T, Zhang GF, Liang PH, Johanson KO, Casper DJ, Doyle ML, Marino JP, Jr, Thompson SK, Chen W, Tew DG, Meek TD. Steady-state kinetic characterization of substrates and metal-ion specificities of the full-length and N-terminally truncated recombinant human methionine aminopeptidases (type 2) Biochemistry. 2001;40:10645–10654. doi: 10.1021/bi010806r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frottin F, Martinez A, Peynot P, Mitra S, Holz RC, Giglione C, Meinnel T. The proteomics of N-terminal methionine cleavage. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:2336–2349. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600225-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addlagatta A, Hu X, Liu JO, Matthews BW. Structural basis for the functional differences between type I and type II human methionine aminopeptidases. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14741–14749. doi: 10.1021/bi051691k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thakkar A, Wavreille AS, Pei D. Traceless capping agent for peptide sequencing by partial Edman degradation and mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:5935–5939. doi: 10.1021/ac0607414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu X, Dang Y, Tenney K, Crews P, Tsai CW, Sixt KM, Cole PA, Liu JO. Regulation of c-Src tyrosine kinase activity by bengamide a through inbition of methionine aminopeptidases. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:764–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang JY, Sheppard GS, Lou PP, Kawai M, Park C, Egan DA, Schneider A, Bouska J, Lesniewski R, Henkin J. Physiologically relevant metal cofactor for methionine aminopeptidase-2 is manganese. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5035–5042. doi: 10.1021/bi020670c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu X, Addlagatta A, Lu J, Matthews BW, Liu JO. Elucidation of the function of type 1 human methionine aminopeptidase during cell cycle progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18148–18153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608389103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li J-Y, Chen L-L, Cui Y-M, Luo Q-L, Gu M, Nan F-J, Ye Q-Z. Characterization of full length and truncated type I human methionine aminopeptidases expressed from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7892–7898. doi: 10.1021/bi0360859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chhabra SR, Parekh H, Khan AN, Bycroft BW, Kellam B. A Dde-based carboxy linker for solid-phase synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2189–2192. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam KS, Salmon SE, Hersh EM, Hruby VJ, Kazmierski WM, Knapp RJ. A new type of synthetic peptide library for identifying ligand-binding activity. Nature. 1991;354:82–84. doi: 10.1038/354082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furka A, Sebestyen F, Asgedom M, Dibo G. General method for rapid synthesis of multicomponent peptide mixtures. Int. J. Peptide Protein res. 1991;37:487–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1991.tb00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser R, Metzka L. Enhancement of cyanogen bromide cleavage yields for methionyl-serine and methionyl-threonine peptide bonds. Anal. Biochem. 1999;266:1–8. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sweeney MC, Pei D. An improved method for rapid sequencing of support-bound peptides by partial Edman degradation and mass spectrometry. J. Comb. Chem. 2003;5:218–222. doi: 10.1021/cc020113+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gevaert K, Goethals M, Martens L, Van Damme J, Staes A, Thomas GR, Vandekerckhove J. Exploring proteomes and analyzing protein processing by mass spectrometric identification of sorted N-terminal peptides. Nature Biotech. 2003;21:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nbt810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo QL, Li JY, Liu ZY, Chen LL, Li J, Qian Z, Shen Q, Li Y, Lushington GHYQZ, Nan FJ. Discovery and structural modification of inhibitors of methionine aminopeptidases from Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:2631–2640. doi: 10.1021/jm0300532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bond CS, White MF, Hunter WN. High resolution structure of the phosphohistidine-activated form of Escherichia coli cofactor-dependent phosphoglycerate mutase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3247–3253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warder SE, Tucker LA, McLoughlin SM, Strelitzer TJ, Meuth JL, Zhang Q, Sheppard GS, Richardson PL, Lesniewski R, Davidsen SK, Bell RL, Rogers JC, Wang J. Discovery, Identification, and Characterization of Candidate Pharmacodynamic Markers of Methionine Aminopeptidase-2 Inhibition. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:4807–4820. doi: 10.1021/pr800388p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turk BE, Griffith EC, Wolf S, Biemann K, Chang YH, Liu JO. Selective inhibition of amino terminal methionine processing by TNP-470 and ovalicin in endothelial cells. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:823–833. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)80129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Towbin H, Bair KW, DeCaprio JA, Eck MJ, Kim S, Kinder FR, Morollo A, Mueller DR, Schindler P, Song HK, van Oostrum J, Versace RW, Voshol H, Wood J, Zabludoff S, Phillips PE. Proteomics-based target identification - Bengamides as a new class of methionine aminopeptidase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:52964–52971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinetz A, Traverso JA, Valot B, Ferro M, Espagne C, Ephritikhine G, Zivy M, Giglione C, Meinnel T. Extent of N-terminal modifications in cytosolic proteins from eukaryotes. Proteomics. 2008;8:2809–2831. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.