Abstract

Objective

To gain insight into the needs of pregnant women during Hurricane Katrina.

Design

Grounded theory using semi-structured interviews.

Setting

Subjects were recruited with flyers. Interviews were conducted in a location preferred by the participant.

Patients/Participants

Eleven participants were interviewed. All were pregnant during the storm, lived in an area impacted by Hurricane Katrina prior to the storm, were between the ages of 18–49, and spoke English.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were performed and recorded, transcribed, and reviewed to organize the women's thoughts into categories.

Results

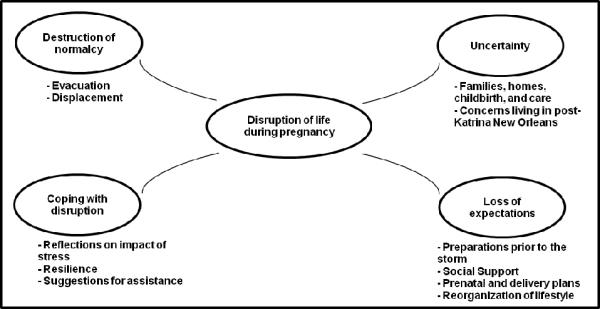

The core category was “disruption of life during pregnancy,” and four additional subcategories were “destruction of normalcy,” “uncertainty,” “loss of expectations,” and “coping with disruption.”

Conclusion

The women relied on family and friends for support. Life in New Orleans for months after the storm was difficult due to unreliable information. Healthcare professionals that interact with pregnant women should move toward use of electronic medical records and educate women about coping with stress during pregnancy.

Keywords: Pregnancy, stress, Hurricane Katrina, evacuation, social support, qualitative analysis

I'm getting induced and I'm watching the TV and I'm watching Mayor Nagin completely break down on TV and all the people break down around him saying, “Where is our help? Where is our help?” and I can remember feeling guilty for being in pain over labor because I felt like the pain that the city and that our people were going through was far greater than anything that I was going through at the time.”

Hurricane Katrina grew to a Category 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall along Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama as a Category 3 storm. The resulting levee failures surrounding Lake Pontchartrain caused the mass flooding in New Orleans, and weeks passed before the water was drained from the city (McQuaid & Schleifstein, 2006).

Previous studies of disaster have shown correlations between stress and adverse health effects in the general population, and the impact of stress manifests differently in mental and physical function among people (Murphy, 1984; Clayer, Bookless-Pratz, & Harris, 1985). Specifically, mental health of disaster victims is particularly affected by stress, loss, and lack of social support (Norris et al., 2002), and the quantity of disaster experiences has been shown to exacerbate risk of mental health problems. Women who experienced at least three adverse life occurrences such as disaster and violence were almost seven times as likely to experience lingering depressive symptoms as women who did not report such experiences (Tanskanen et al, 2004). Women have also been shown to have more severe Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) than men in the same disaster experience (Verger et al, 2003; Galea et al, 2007).

This study specifically explores women's experiences with pregnancy during the unique circumstance of a natural disaster, in this case the evacuation and devastation resulting from Hurricane Katrina. Although research pertaining to the effects of disaster on pregnant women is limited, existing research generally concludes that disaster has an adverse effect. For example, the impact of a flood disaster on 47 pregnant women in Poland showed that 55.3% of study participants experienced miscarriage, fetal death, or other adverse outcomes, along with other physical and mental complications that were associated with stress (Neuberg, Pawlosek, Lopuszanski, & Neuberg, 1998). Prenatal maternal stress has also been associated with an increased risk for preterm birth and adverse mental health outcomes in child development (Beydoun & Saftlas, 2008). Current literature has not explored the women's perception of disaster during pregnancy.

The needs specific to reproductive health and expecting mothers, such as basic prenatal care and accessibility to medical personnel, must be recognized in order to implement effective emergency preparedness plans. Therefore, understanding the impact of disaster serves the purpose of providing resources that will effectively allow people to cope with loss and stress while maintaining public health. Qualitative research of disaster victims provides uniquely detailed information as grounds for further investigation. The objective of this study was to examine the experiences of women pregnant during Hurricane Katrina, the impact of the disaster on their lives, and the implications that may be drawn from concepts outlined in the data.

METHODS

Design and Sample

Grounded theory methodology was used to learn about the process of childbearing during a natural disaster and dealing with the recovery through women's perspectives. The interview questions evolved based on issues revealed by the women (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Women were eligible for this study if they were English-speaking, in any stage of pregnancy at the time of Hurricane Katrina, and between the ages of 18 and 49. Participants initially contacted the researchers due to interest in a larger cohort study of postpartum mental health but were ineligible because they had already given birth. To further recruit participants, flyers were distributed in Tulane and Lakeside Hospitals and clinics. Four women were interviewed at their homes, five women were interviewed at the Tulane research center, one woman was interviewed at a coffee shop, and another woman was interviewed at her place of employment (N=11). All the women carried their babies to term, although four women mentioned prior pregnancies that had ended in miscarriages.

Instrument

The principal investigator conducted ten of the interviews. Another researcher participated in study design development and recruitment and conducted one of the interviews. The interviews were semi-structured with open-ended questions that pertained to four general areas: thoughts on pregnancy before the storm; Hurricane Katrina/evacuation experience; access to health care during evacuation and after returning to New Orleans; and perceived impact of stress on diet, physical activity, pregnancy, infant care, and postpartum. These questions covered topics pertaining to pregnancy and disaster but allowed the participants to provide their own interpretation of their disaster experiences and pregnancies.

Procedure

All protocols in this study were approved by the Tulane University Institutional Review Board. Every participant was introduced to the study with a consent form which explained the purpose of the study and their roles as participants. This document was signed by all participants before the interviews began. All interviews were conducted in a private location chosen by the participant, tape-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Interviews included in the analysis lasted on average about 35 minutes (minimum: 16 minutes, maximum: 1 hour and 15 minutes) and occurred between October 2006 and July 2007 (a course of ten months). Qualitative analysis software was used to code the 99 pages of text. Two additional researchers read the transcriptions and discussion among the researchers was done to reach consensus of major concepts and develop categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

CALLOUT 1

RESULTS

The core category for this analysis was “disruption of life during pregnancy.” Every woman described how they envisioned their pregnancies would be prior to the hurricane. This pregnancy plan provided a sense of security. Katrina disrupted these plans and challenged women's ability to cope with uncertainty. Four additional categories emerged from the eleven interviews to elaborate this core concept, including “destruction of normalcy,” “uncertainty,” “loss of expectations,” and “coping with disruption” (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Four subcategories surrounding the core category of pregnant women's experiences during Hurricane Katrina.

Destruction of normalcy

Evacuation

Characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. All of the 11 women eventually evacuated New Orleans, but three women sought refuge in the city during the storm. These three women all expressed depression and had some of the most dramatic stories. These women did not evacuate because they wanted to avoid spending hours in cars or had no transportation with which to leave the city. Concerns for their babies and fear of death were mentioned by all three women who were later forced to evacuate the storm's aftermath:

I thought we were gonna die. I really did. I mean the building just didn't seem like it was going to hold up… Then…the emergency system started going off in the building saying too that everyone had to evacuate…and I'm meanwhile starting to kind of have cramps. Actually the only thing I knew was if water gonna come through, we're gonna die, can't swim, I'm gonna die.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Interviewed Women Pregnant During Hurricane Katrina (n=11)

| MARITAL STATUS | N |

|---|---|

| Married | 9 |

| Single (but with partner) | 2 |

| EMPLOYED | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 8 |

| No | |

| Unknown | 3 |

| YEARS RESIDING IN NEW ORLEANS | |

|---|---|

| ≤18 | 4 |

| >18 | 7 |

| PARITY | |

|---|---|

| 1st | 7 |

| 2nd | 2 |

| 3rd | 1 |

| 4th | 1 |

| GESTATION AT HURRICANE | |

|---|---|

| <20 weeks | 5 |

| 20–29 weeks | 4 |

| 30–39 weeks | 2 |

| EVACUATED | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 8 |

| No | 3 |

| HOME FLOODED | |

|---|---|

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 4 |

Two of the three women's significant others were helping with boat rescues when the city began to flood. Displacement of loved ones was a reality in the flood evacuation as one woman expressed fear of separation from her partner, “My husband, he did rescues … I started worrying 'cause I was wondering where he was and I refused to get on any helicopter… without him.”

Women described their nutritional status as inadequate but most continued to take prenatal vitamins. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle of cooking meals and exercising was not sustainable during the evacuation and most women ate snack foods to satiate themselves: “If you couldn't walk and get your own food, like stand in them long lines, and sometimes people stand in line, three or four times and they run out… Some days I didn't eat at all.”

I was feeling just incredibly guilty like I was taking a meal away from somebody but… I knew that I needed to feed my baby… it was a very just humbling experience because…my dad's almost 70 and my mom is 65 and my husband [were] sitting and watching me eat…this meal, and I knew that they were hungry too, and I just remember…feeling this huge amount of guilt…like I was taking food from them.

Among the three women who did not evacuate, one woman delivered at 39 weeks by vaginal birth just days after the storm, another at 37 weeks by Cesarean delivery four months after Katrina, and the other woman delivered at 28 weeks gestation by Cesarean delivery the month after the hurricane. “I was so stressed out and they told me I had a ruptured placenta and made me -- I had to take my baby early; she was two pounds.”

The women who did evacuate took clothes for several days, snack food, and a few irreplaceable items. The perceptions of the evacuation process varied across all stages of gestation. For some women, sitting for several hours at a time in traffic was uncomfortable. Other women expressed a preference for being pregnant during an evacuation rather than caring for an infant. At 28 weeks gestation, one woman said, “It would have been a lot easier to deal with the storm I think mentally if I had not been pregnant.” At 12 weeks gestation another said, “I think [my sister] may have had more stress during the hurricane with the new baby than I did being pregnant, because… she has to go through all this for the baby, but at least my baby is safe inside.”

Displacement

Life was disorganized in the city immediately after the hurricane and during the flood. Family members were separated, and cell phones were not functioning so communication was limited. Power outages prevented media from distributing information about road closures and flooding, which left people unaware of the reason for the rising water. One participant described feeling disconnected from the rest of the world, “We didn't have a portable TV, so I didn't really know what was going on in the city. The batteries died in the radio… You know everybody was trying to figure out what was going on and it's like everybody's cell phone was dead so nobody knew where nobody was.”

While the storm displaced and separated families, the evacuation provided some women with the opportunity to spend time with other family members, “It felt good to just be hugged by my mom. …for them it was really exciting because it's their first grandchild and they got to see pictures of him live, actual moving pictures and not just what grandparents usually see: the oh, here's four pictures they printed out for us.”

Uncertainty

Family, homes, childbirth, and care

All the women believed that normal life would resume after several days. After evacuating and learning the severity of the flood, questions began to arise about their pregnancies, medical access, status of their homes, and their futures. Women described feelings of frustration with their temporary living situations, unfamiliarity with their surroundings, and uncertain futures. Living with friends or family was convenient, but privacy and space were lacking. Further, these arrangements were not sustainable for the months that many women had to remain evacuated.

Every woman described frustration of not knowing the answers to questions about their lives. Developing a plan for recovery was difficult since the extent of damage was unknown. Further, women were further stressed by separation from family members who also fled and not knowing where these family members were. “Everybody was trying to get in touch with us, and we were trying to get in touch with all other friends and family, and it was very difficult and stressful not knowing where anybody was.” Another participant related, “I still didn't know what had happened to my parents at this point because we had not heard from them, and I was getting more and more anxiety ridden about that.”

In addition to missing family and friends and the uncertain status of their homes, prenatal care, delivery, and jobs compounded the stress of the participants. For some women the fear of losing their homes and jobs became a reality. Many of them had spent most of their lives in New Orleans and consequently felt committed to the city but were unsure how their lives could flourish with the extent of damage. For others the process of rebuilding every aspect of their lives became a reality. A number of major life questions left to be answered faced the women:

We started getting scared and worried …what was our house like, what was our home like, and what was the city that we loved and grew up in? What was going to happen, what was going to go on, where were we going to go? What about our belongings and our pictures, memories? And you know everything was gone.

Of course the stress of not knowing, 'cause you would look for your house on television, at least look in the area, and of course they were only showing the French Quarter and all those places.

I was scared my child wouldn't have somewhere to sleep and to have that fear is scary, that not knowing what was going to happen.

Since residents were not allowed into the city for weeks after the flood, the women did not know if they should build new relationships with OB/GYNs in other cities:

I did not know what was going on with our lives at that point and time and I wasn't sure how I could function in the disruption of everything with taking care of my two older children and being pregnant… what was going to happen with the third [child] and the destruction of the city and the condition of the hospitals and… who would deliver the baby and who would I see to have check-ups and just a lot of insecurity.

I've lost my OB, I've lost a hospital…this OB that's just giving me an ultrasound to make sure that the baby's ok I know isn't going to be my OB- where are we having this baby, where, where are we going to live, are we going back to New Orleans?

We were put on Medicaid because I lost my insurance with the storm…so that was a huge stress. I was extremely upset about that because I didn't know how we were gonna pay to have this baby.

Yet the painful realities that surfaced when the water receded were more manageable than not knowing anything. Once the status of their homes was known the women could plan what needed to be done to rebuild order in their lives, “We had water up to the second step from the top…so I felt better knowing what happened. It was the not knowing was more stressful.”

It was pretty rough to live here right at the beginning… utilities were kind of hit or miss, there'd be times when the electricity would be out or the water pressure wouldn't be up…but… if you don't know anything else, than you…deal with it versus… the chaos of living in a place that wasn't home.

Concerns Living in Post-Katrina New Orleans

Locating daycares and getting appointments with pediatricians after returning to the city was also difficult because websites were not updated and phone numbers were out of service. Women described a difficult balancing act of rebuilding their lives in a city slowly recovering while also preparing to deliver a baby or caring for an infant:

How am I going to save my baby? What if he gets sick? …Hearing that there were very few doctors in the city and I did not trust hospitals by that time- at all- especially in the city.

Every free second I got I was on the phone making phone calls, changing my address, trying to take care of bills,… trying to turn off electricity and then running to the store to go get things.

Women frequently mentioned mold exposure as an environmental concern for their infants; mold was a constant problem due to humidity, and debris was still ubiquitous for months after the storm, “I immediately had concern that she was gonna get asthma. I just thought, there's gotta be so many mold spores in the air here; God knows what's in the ground water.”

Loss of expectations

Preparations prior to the storm

At the time of the storm women ranged in gestation from 10 to 39 weeks; some women were just beginning to share their pregnancy news with family and coworkers, while others were far enough along that they were making preparations for the baby's arrival, “The weekend that Katrina hit we were going to pick out paint samples, our crib was in, and we were doing the nursery. Instead we boarded up our windows.”

Some women returned weeks after the storm and others returned months later. All women experienced some form of loss, whether they lost belongings, jobs, homes, or social support. The homes of seven of the eleven women flooded, but all the women temporarily lost the comfort of having a plan for their pregnancies:

All my baby[s] ultrasounds was in her little book I bought her and that drowned too. Pictures of the family are gone; my mother in law when she died left things to my husband - all those is gone.

One thing that I was doing that was really relieving a lot of stress…was taking prenatal yoga classes and…I met a lot of women in there that were the same stage of pregnancy that I was, and so… when that was gone…that was rough, because it was really something that helped me out a lot.

Social support

Arrangements for daycares, plans for baby showers, and delivery preparations had been made prior to the storm. Families and friends had supported them through their pregnancies, and the women planned to rely on that support system after their babies were born. Some women also expressed frustration by not having a release to cope with the stress like the general population because of medical restrictions for their pregnancies:

I was excited to have my friends around to support me [with my first baby] we didn't have a shower so I was kind of looking forward to that and I just thought… I'm gonna have a lot of support around me this time, so I was looking forward to that.

I felt alone… because everybody had left me. I was pregnant by myself in this town that I didn't know.

In between contractions my husband was going from me to putting cereal on the table and then back to me and running upstairs and putting clothes on. We didn't have anybody just to rush over… to help us out…If we were in pre-Katrina times, we had several friends right around the corner from us that could have just walked over and helped us out.

My husband…was spending probably 3–4 hours a day commute time, so he wasn't at home most of the time, and if that's the person who you vent to or you're used to spending leisure time with and they're not around, that's also very stressful.

Prenatal Care and Delivery Plans

The experiences with prenatal care and deliveries during and after evacuation varied among the women. Most women expressed that the process of making prenatal appointments with other doctors in the absence of medical records was not difficult given their circumstances; their experiences were not ideal but manageable. Some women's deliveries went smoothly. At the same time an influx of people in Baton Rouge and the hospitals surrounding New Orleans coupled with less hospital staff meant that some services were not provided for deliveries in some cases:

I was back where I felt comfortable in that hospital that I knew…My doctor actually didn't deliver me, but the hospital was wonderful. I was one of two people giving birth at the time, because people hadn't gotten back, but they were open, full staff and everything.

Another participant explained:

Unless you were having literally a baby in the lobby, they could not give me a bed because 50 women had given birth that day I believe, on that Tuesday. The babies were getting stacked in Woman's Hospital…there was no room.

Women still had to make prenatal visits and delivery preparations for the weeks/months leading up to their return. Evacuating from a disaster area meant the women had to establish relationships with new doctors without having access to their medical records:

All my medical records was lost in New Orleans, so every doctor you go to they always want to do their own tests… so basically I had the same tests over and over and over. I've seen I think maybe …four different doctors through that pregnancy all in different places… as you get further in the pregnancy, everything starts to get real tender on you…and it's aggravating; you don't want to be fooled with constantly.

Reorganization of lifestyle

The women elaborated on their difficulties with obtaining resources to restock their homes and for baby needs in the months after returning to the city. Few grocery stores were open in New Orleans, and the stores that were functioning did not have the supply to meet the demand of returned evacuees. This limited supply of goods required women to either make do or travel to neighboring cities to purchase items. Even purchases through the internet were difficult because the mail service was slow and unreliable:

I couldn't find baby food half the time on the shelves…Getting in to see a pediatrician here was really difficult because there's not enough of them to see all of the patients and since their schedules are constantly changing, or there might be this emergency or that emergency, or they're rebuilding their house, too.

Coping with disruption

Reflections on impact of stress

Prior to Hurricane Katrina all the women thought they would be focusing on their pregnancies and manage normal daily stressors. After the storm the women expressed other issues required immediate attention so their pregnancies took the backseat:

I just tried to take care of myself the best that I could, but it…was almost the last priority…, which is a shame; it should be the first thing I think of. But I had all these other worries, and I have a six year old son that was …having nightmares and at a new school and new place.

Women reflected about their stress from the uncertainty that developed as a result of the storm, the unusual circumstance of having to rebuild their lives, and how these obstacles might have affected their pregnancies:

It was very surreal and the labor and the delivery was… nothing compared to what we had already been through.… it's almost kind of sad now when I think about it, because the birth of your child should be this joyous, wonderful, emotional occasion, and I was almost numb.

I wonder about the stress… I mean, for six solid weeks of stress when you're so on edge and so short-tempered, does that cause problems … did that cause the pre-eclampsia? Was my stress so high and my body saying, “You need to take care of yourself and I'm gonna make you take care of yourself by basically putting you in organ failure until your baby's born?”

Four women had experienced miscarriages prior to the storm, but most women interviewed were worried about not carrying the baby to term and the impact of stress post-Katrina would have on their babies. Most women referred to prior knowledge they had that stress was not good for the womb, “I definitely felt it [effect of hurricane] physically…the stress was huge.… I think you know the number-one thing that you read and …the doctors say is … avoid stress as much as you possibly can, and we had more than we've ever had in our lives …and it was unavoidable.”

Resilience

In some cases, the loss of one social support system was followed by another support system such as coworkers. Some women managed the stress by gaining the perspective that they needed to be grounded for their health and their babies, “I knew that I had to be strong for him [my son]. He was the most important thing in my life at that point …If I [was] stressed out, I wasn't going to be producing milk.” “It [the storm] was completely life changing because I became a better person after it all happened. I just started to want to help people because so many people rose up to help us.”

Women also found comfort in their jobs and used that responsibility to maintain focus and direction while other aspects of their lives were disorganized:

It [work] was a needed distraction. It was less stressful to worry about getting that together than to worry about what my own situation was.

I work on a faculty of six women who I sit and have lunch with every day that I'm very close to. And so probably that was another support system that wasn't in place, because really we would teach and then leave and so we didn't have a lot of interaction, except on the phone or emails.…That wasn't the same as having that day to day sort of office support from your co-workers who had children and had experience.

For some women the hurricane temporarily relieved them of their job responsibilities because the city was hardly functional. This opportunity allowed women to focus on their pregnancies, be with family, and rest when they needed to without having to use leave-time from work, “As often as I got sick during the hurricane, I said this is somewhat of a blessing in disguise because if I was at work I would have had to take all this time off.”

Suggestions for assistance

Women indicated that support systems and better access to updated information about the city would have made the rebuilding process easier. The movement of people back into a devastated city created more burdens with fewer workers, which consequently put more responsibility on less staff. This lack of availability was experienced in hospitals, retail establishments, and public services such as mail service and home repairs:

Just to have a list of pediatricians … what their real hours are and what they're really seeing for patients and childcare…parent-wise the hardest part is just the lack of quality resources. What are the parents' groups that you would want to be a part of, which children's stores are actually open because they say that they're open, they've got signage, but then they're not open.

Having access to medical records. If they were online, I wouldn't have had such a problem getting a physician.

DISCUSSION

Prior to the hurricane the women were comforted by knowing where they were going to deliver and having an established relationship with their doctors for prenatal visits. They were also comforted by having their homes prepared for their babies' arrivals, social support, and a plan for their lives after their babies were born. All these comforts were wiped away when the levees breached.

Dealing with loss was a major aspect of life for the women during the evacuation and living in post-Katrina New Orleans. Locating functioning stores, daycare centers, and doctor's offices was a challenge; for several months after the storm, few stores were open, hours of operation were shortened, and the supply of goods was minimal. Several participants expressed gratitude for the Red Cross and generosity from the general population for their contributions of food and clothing, which helped the women to rebuild their lives.

The most significant losses expressed by the women were social support, jobs, homes, and the comfort of a life plan. The uncertainty that filled so many aspects of their lives invoked stress and in some instances feelings of depression. Previous research among residents of Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) housing post- Katrina and Rita indicated that uncertain living situations, such as the number of times an individual relocated, were associated with a decline in mental health (Abrahamson, Stehling-Ariza, Garfield, & Redlener, 2008). Pre-Katrina residents of New Orleans in another study showed an increase in anxiety-mood disorders compared to other Gulf Coast areas affected by the storm (Galea et al, 2007).

Social support was noted as a significant coping measure, and several women suggested that a support system in New Orleans post-Katrina would have been beneficial. Previous research indicated the presence of social support is positively correlated with mental health (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993; Abrahamson et al, 2008). The hurricane created disorder in the participants' lives, but some women also described positive experiences, such as the opportunity to be with families or other relatives and to maintain bed rest without compromising their jobs.

Limitations

The results of this study only pertain to the population of women that returned to New Orleans, not women permanently displaced. The interviews were conducted almost two years after the storm, and the answers may have been different if they had been collected closer to the women's return. While these are significant limitations, the thoughts and concerns expressed by the participants in this study provide insight into their experiences and their perceptions of the storm on their pregnancies. Knowledge of patients' experiences and general perceptions may help professionals who interact with disaster victims to more effectively address their concerns.

Implications

Since most of these women still sought interaction with physicians for follow-up visits or infant care, healthcare professionals have the opportunity to assist women with regaining normalcy. Research of FEMA housing residents along the Gulf showed that recovering this normalcy in a social sense was advantageous to disaster victims (Abrahamson et al, 2008). To start with, healthcare professionals can make their operating hours, availability, and new patient practices clear and consistent and have this information available in as many places as possible. All personnel in an office can work together to make sure messages are straightforward and consistent. To the extent possible, healthcare providers can also serve as sources of information on topics such as child care and baby supplies.

After returning to the city women were frustrated by non-working phone numbers of daycare centers and stores. Community services could make maternal-child items available or refer women to other resources. Some women also expressed frustrations due to inaccessibility of their medical records. The use of electronic medical records would promote timely and easy transmission of information between healthcare professionals as long as remote, protected servers were maintained (Potash, West, Corrigan, & Keyes, 2009). Women would also have more control over access to their records and the opportunity to carry hard copies.

CALLOUT 2

Even women who felt they were coping well during and after the disaster still experienced loss. Depression was experienced by at least three women who described related symptoms and were diagnosed by a physician. Nurses can collect information on how pregnant women coped with stress prior to the disaster and encourage them to use these techniques again. A previous study among postpartum women living in post-Katrina New Orleans showed disaster experience was associated with decreased mental health (Harville, Xiong, Pridjian, Elkind-Hirsch, & Beukens, 2009). Methods of coping with loss should be ascertained by healthcare professionals who treat victims of disaster. Nurses can promote stress reduction and childbirth education. Before hurricane season, nurses interacting with pregnant women have the opportunity to assist them with preparing a disaster plan that fits their unique needs (Ewing, Buchholtz, & Rotanz, 2008).

CALLOUT 3

Conclusion

Uncertainty and coping with stress were expressed by every women interviewed. Some women contemplated the effect Katrina might have had on their pregnancies. Nurses and other healthcare professionals can reassure women that healthy babies have been delivered despite disasters experienced during pregnancies. Educating women on stress coping mechanisms and encouraging them to have an emergency plan would also give women a sense of control and focus. The impact of the disaster experience on pregnancy is beyond the interpretive boundaries of this study, but quantitative research of stress and birth outcomes among women in various stages of gestation at the time of a disaster as well as additional long-term qualitative studies among disaster victims are suggestions for further research.

Callouts.

Katrina disrupted pregnancy plans and challenged women's ability to cope with uncertainty.

Nurses can collect information on how pregnant women coped with stress prior to the disaster, and encourage them to use these techniques again.

Nurses and healthcare professionals have the opportunity to reassure women that healthy babies have been delivered despite disasters experienced during pregnancies.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R21 MH078185-01 and K12HD043451. The authors thank Dr. Tina Strickland for conducting one of the interviews and assisting with participant recruitment.

References

- Abrahamson D, Stehling-Ariza T, Garfield R, Redlener I. Prevalence and predictors of mental health distress post-Katrina: Findings from the gulf coast child and family health study. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Practice. 2008;2:77–86. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318173a8e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun H, Saftlas AF. Physical and mental health outcomes of prenatal maternal stress in human and animal studies: a review of recent evidence. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2008;22:438–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayer JR, Bookless-Pratz C, Harris RL. Some health consequences of a natural disaster. Medical Journal of Australia. 1985;143:182–184. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb122908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Buchholtz S, Rotanz R. Assisting pregnant women to prepare for disaster. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2008;33:98–103. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000313417.66742.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones R, King DW, King LA, Kessler RC. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Xiong X, Pridjian G, Elkind-Hirsch K, Beukens P. Postpartum mental health after Hurricane Katrina: A cohort study. BioMed Central Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:395–408. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid J, Schleifstein M. Path of destruction: The devastation of New Orleans and the coming age of superstorms. Little, Brown and Company; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SA. Stress levels and health status of victims of a natural disaster. Research in Nursing & Health. 1984;7:205–215. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770070309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberg M, Pawlosek W, Lopuszanski M, Neuberg J. The analysis of the course of pregnancy, delivery and postpartum among women touched by flood disaster in Kotlin Klodzki in July 1997. Ginekologia Polska. 1998;69:866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash MN, West JA, Corrigan S, Keyes MD. Pain management after Hurricane Katrina: outcomes of veterans enrolled in a New Orleans VA pain management program. Pain Medicine. 2009;10:440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tanskanen A, Hintikka J, Honkalampi K, Haatainen K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Viinamaki H. Impact of multiple traumatic experiences on the persistence of depressive symptoms--a population-based study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;58:459–64. doi: 10.1080/08039480410011687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verger P, Rotily M, Hunault C, Brenot J, Baruffol E, Bard D. Assessment of exposure to a flood disaster in a mental-health study. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology. 2003;13:436–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]