Abstract

Background:

Extended exposure to low levels of lead causes high blood pressure in human and laboratory animals. The mechanism is not completely recognized, but it is relatively implicated with generation of free radicals, oxidant agents such as ROS, and decrease of available nitric oxide (NO). In this study, we have demonstrated the effect of ascorbic acid as an antioxidant on nitric oxide metabolites and systolic blood pressure in rats exposed to low levels of lead.

Materials and Methods:

The adult male Wistar rats weighing 200-250 g were divided into four groups: control, lead acetate (receiving 100 ppm lead acetate in drinking water), lead acetate plus ascorbic acid (receiving 100 ppm lead acetate and 1 g/l ascorbic acid in drinking water), and ascorbic acid (receiving 1 g/l ascorbic acid in drinking water) groups. The animals were anesthetized with ketamin/xylazine (50 and 7 mg/kg, respectively, ip) and systolic blood pressure was then measured from the tail of the animals by a sphygmomanometer. Nitric oxide levels in serum were measured indirectly by evaluation of its stable metabolites (total nitrite and nitrate (NOχ)).

Results:

After 8 and 12 weeks, systolic blood pressure in the lead acetate group was significantly elevated compared to the control group. Ascorbic acid supplementation could prevent the systolic blood pressure rise in the lead acetate plus ascorbic acid group and there was no significant difference relative to the control group. The serum NOχ levels in lead acetate group significantly decreased in relation to the control group, but this reduction was not significantly different between the lead acetate plus ascorbic acid group and the control group.

Conclusion:

Results of this study suggest that ascorbic acid as an antioxidant prevents the lead induced hypertension. This effect may be mediated by inhibition of NOχ oxidation and thereby increasing availability of NO.

Keywords: Blood pressure, lead, ascorbic acid, nitric oxide

Introduction

Chronic exposure to low levels of lead causes high blood pressure in human and laboratory animals which persists after cessation of lead exposure.[1,2] The mechanism is not completely understood, but it seems to be related to generation of free radicals, oxidant agents such as ROS, and decrease of available nitric oxide (NO). Exposure to low levels of lead causes the production of free radicals such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, oxygen, and hydrogen radicals.[3‐5] Oxidative stress plays an important role in lead-induced hypertension through inactivation of nitric oxide (NO) by ROS. Alleviation of oxidative stress using antioxidants could decrease blood pressure and increase available nitric oxide (NO) in lead-induced hypertension.[6,7] Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) a water soluble vitamin that is one of the important antioxidants in plasma and cell membranes that could act as a free radical (specially superoxide anion) scavenger and could increase the available nitric oxide through both protection from oxidation and increase in eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase) activity.[8,9] Ascorbic acid also is associated with a reduction in vascular sensitivity to noradrenaline and enhancement of endothelium-dependent relaxation due to increased nitric oxide bioavailability.[10‐12]

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of ascorbic acid supplementation as an antioxidant on blood pressure and nitric oxide metabolites level (total nitrite and nitrate (NOχ) after acute (4-8 weeks) and subacute (12 weeks) exposure to low levels of lead acetate in rats.

Materials and Methods

Adult male Wistar rats weighing 200-250 g were divided into four groups: control (CNTL), lead acetate (Ld) (receiving 100 ppm lead acetate in drinking water), lead acetate plus ascorbic acid (Ld+AA) (receiving 100 ppm lead acetate and 1g/l ascorbic acid in drinking water), and ascorbic acid (AA) (receiving 1 g/l ascorbic acid in drinking water) groups. The animals were anaesthetized with ketamin/xylazine (50 and 7 mg/kg, respectively, ip) and then systolic blood pressure were measured from the tail of the animals by a sphygmomanometer (PE300, Narco Biosystems) after stabilization of vital signs. Nitric oxide levels in serum were measured indirectly by evaluation of its stable metabolites nitrite and nitrate by the spectrophotometric method using the Griess reaction. A good correlation between endogenous NO production and nitrite/nitrate (NOχ) levels in plasma, serum, and urine has been reported.[13] In the present study, nitrate was reduced to nitrite by vanadium chloride(III). Diazotization of sulfanilamide by nitrous acid and its conjugation with a bicyclic amine produced a chromophore which had maximum absorbance at 540 nm.[14,15] In addition, the weight of animals was measured in different weeks. Blood ascorbic acid concentration was measured in each group after 12 weeks using the spectrophotometric method. The serum ascorbic acid was reduced to dehydroascorbic acid by Cu2+and then conjugated with the aromatic dinitro-phenyl hydrazine to produce a chromophore which had maximum absorbance at 520 nm.[16]

Statistics

Statistical comparison of data between the experimental groups with those obtained from the control group was performed by one-way ANOVA and then the Tukey-HSD test. The repeated measurement method used for comparison of data from the same groups but in different weeks. In all cases, a value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Results

Animal Weights

There was no difference in animal weights among different experimental groups and the CNTL before the experiment and after 4, 8 and 12 weeks of receiving lead acetate and ascorbic acid [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Animal weights in different groups. (CNTL: control group; AA: ascorbic acid group; Ld: lead acetate group; Ld+AA: lead acetate + ascorbic acid group)

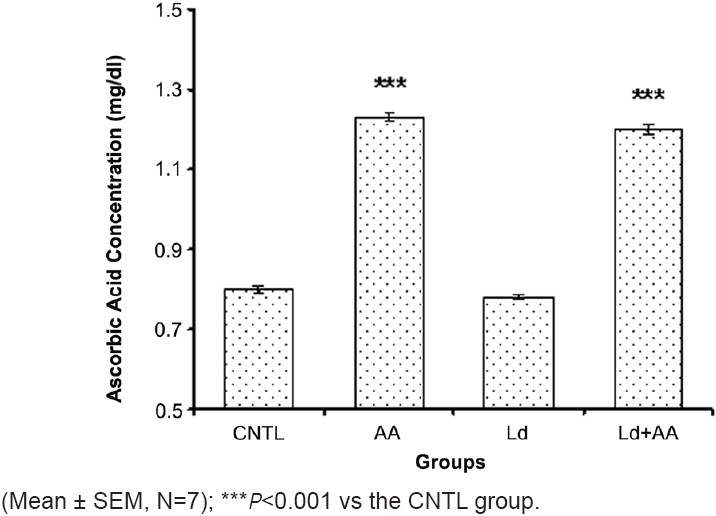

Ascorbic Acid

The serum ascorbic acid concentration in the AA group (1.23 ± 0.01 mg/dl) and Ld+AA group (1.2 ± 0.01 mg/dl) was significantly higher than that in the CNTL group (0.8 ± 0.008 mg/dl) and Ld group (0.78 ± 0.007 mg/dl) after 12 weeks [Figure 2]. There was no significant difference in the serum ascorbic acid concentration between the AA group and Ld+AA group, as well as between the CNTL group and Ld group after 12 weeks [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

The serum ascorbic acid concentration on 12th week

Blood Pressure

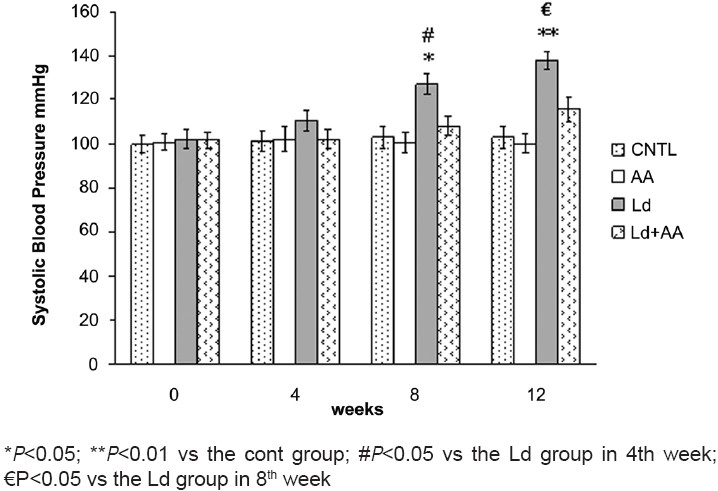

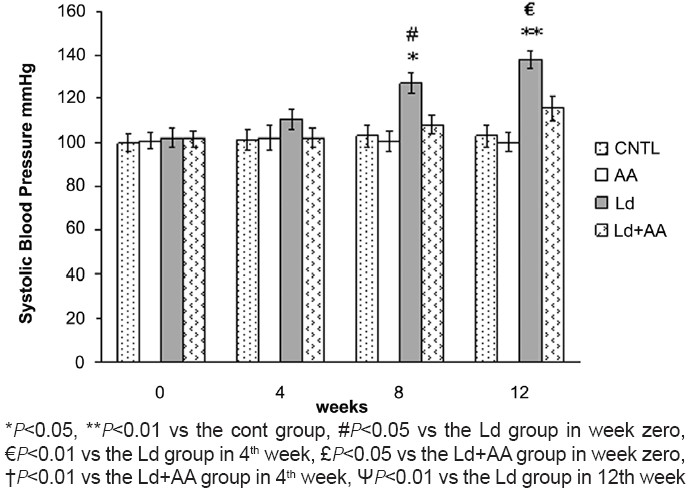

After 4 weeks of lead treatment, systolic blood pressure in the Ld group was elevated (110.28 ± 4.88 mmHg) but was not significantly different in comparison with the CNTL group (101.28 ± 4.55 mmHg). Persistent usage of lead acetate increased the systolic blood pressure significantly to 127.14 ± 4.83 mmHg and 137.85 ± 4.14 mmHg level after 8 and 12 weeks, respectively, as compared to the value in the CNTL group [Figure 3]. No significant difference in the systolic blood pressure between the Ld+AA group and the CNTL group in 4th, 8th and 12th week was seen. There was no significant difference in the systolic blood pressure of the AA group and the CNTL group in 4th, 8thand 12th week [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Measurement of systolic blood pressure (Mean ± SEM, N=7)

Nitric Oxide

After 4 weeks, the NOχ level in the Ld group (46.05 ± 1.69 μM) significantly decreased relatively to the CNTL group (54.18 ± 1.63 μM) [Figure 4]. Prolonged administration of lead acetate ended into a more decrease in NOχ level, there was a significant decrease in NOχ level in the Ld group after 8 weeks (39.03 ± 2.10 μM vs 53.77 ± 1.59 μM) and after 12 weeks (32.12 ± 1.57 μM vs 52.06 ± 1.96 μM) as compared to their corresponding control value. NOχ level in the Ld group after 8 weeks significantly decreased relatively to NOχ level in the Ld group before the experiment. Also, there was significant decrease in NOχ level in the Ld group after 12 weeks in comparison with the NOχ level in the Ld group after 4 weeks [Figure 4]. There was no significant difference in NOχ level between the Ld+AA group and the CNTL group, nor between the AA group and the CNTL group in 4th, 8th, and 12thweek. On the other hand, there was a significant difference in NOχ level between the Ld group and the Ld+AA group after 12 weeks [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Measurement of NOχ concentration (Mean ± SEM, N=7)

Discussion

The present study reveals that ascorbic acid can prevent the lead-induced hypertension via blocking NO oxidation by ROS and NO reduction. In the present study, administration of lead acetate and ascorbic acid in drinking water had no effect on food intake and water drinking. Karimi et al. reported similar results.[17] After 4 weeks, the systolic blood pressure increased, however non-significantly. Systolic blood pressure elevation was significant after 8 weeks of lead exposure and remained elevated after 12 weeks. These results are in agreement with another report by Ding et al.[18]

Administration of ascorbic acid prevented the lead-induced hypertension; however, it seems that this prevention was not complete, nevertheless, there was no significant difference in the systolic blood pressure between the Ld+AA group and the CNTL group. There was a significant decrease in NOχ level in the Ld group relative to the CNTL group in 4th, 8th, and 12th week. Although the NOχ level in the Ld+AA group had decreased in comparison with the CNTL group in 4th, 8th, and 12th week, but it was not significant and it seems that the administration of ascorbic acid could prevent the decrease in NOχ level and this prevention is not complete.

In recent studies, a good correlation has been reported between the blood lead levels and the hypertension.[1] High blood pressure has been reported in both acute and chronic exposure to lead.[19] In many studies, chronic exposure to low levels of lead caused a permanent increase in blood pressure.[20] Lead-induced hypertension have a close correlation with the increase in free radicals production and changes in nitric oxide metabolism.[21,22]

It is also known that the changes in blood nitric oxide level is not solely the cause of lead-induced hypertension[18,23] and the other factors such as changes in ACE activity, in Ang II level, EDCF, endothelin, and in vascular responsiveness might be involved.[23,24]

Conclusion

The results of this study reveal that the decrease in available NO is the main mechanism of lead-induced hypertension, and ascorbic acid supplementation prevents the lead-induced hypertension via inhibition of NO oxidation and an increase in available NO.

Footnotes

Source of Support:Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Sharp DS, Becker CE, Smith AH. Cronic low-level lead exposure: Its role in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Med Toxicol. 1987;2:210–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03259865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harlan WR. The relationship of blood lead levels to blood pressure in the US population. Environ Health Perspect. 1988;78:9–13. doi: 10.1289/ehp.88789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaziri ND. Pathogenesis of lead-induced hypertension: Role of oxidative stress. J Hypertension. 2002;20:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NI Z, Hou S, Barton CH, Vaziri ND. Lead exposure raises superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in human endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2329–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding Y, Gonick HC, Vaziri ND. Lead-induced hypertension: Increased hydroxyl radical production. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:169–73. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaziri ND, Liang K, Ding Y. Increased nitric oxide inactivation by reactive oxygen species in lead-induced hypertension. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1492–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurer H, Ercal N. Can antioxidants be beneficial in the treatment of lead poisoning? Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:927–45. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padayatty SJ, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee JH, et al. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: Evaluation of its role in disease prevention. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22:18–35. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang A, Vita JA, Venema RC, Keaney JF. Ascorbic acid enhances endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activity by increasing intracellular terahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17399–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newaz MA, Yousefipour Z, Nawal N. Modulation of nitric oxide synthase activity in brain, liver, and blood vessels of spontaneously hypertensive rats by ascorbic acid: Protection from free radical injury. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2005;27:497–508. doi: 10.1081/CEH-200067681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uscio L, Milstien S, Richardson D, Smith L, Katusic Z. Long-term vitamin C treatment increases vascular tetrahydrobiopterin levels and nitric oxide synthase activity. Circ Res. 2003;92:88–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000049166.33035.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ettarh RR, Odigie IP, Adigun SP. Vitamin C lowers blood pressure and alters vascular responsiveness in salt-induced hypertension. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:1199–202. doi: 10.1139/y02-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granger DL, Taintor RR, Boockvar KS, Hibbs JB. Measurement of nitrate and nitrite in biological samples using nitrate reductase and Griess reaction. Methods Enzymol. 1996;268:142–51. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun J, Zhang X, Broderick M, Fein H. Measurement of nitric oxide production in biological systems by using Griess reaction assay. Sensors. 2003;3:276–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roe JH. Ascorbic acid. In: Gyorgy P, Pearson WN, editors. The Vitamins. New york: Acad Press; 1976. pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karimi GR, Khoshbaten A, Abdollahi M, Sharifzadeh M, Namiranian KH, Dehpour AR. Effects of subacute lead acetate administration on nitric oxide and cyclooxygenase pathways in rat isolated aortic ring. Pharmacol Res. 2002;46:31–7. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(02)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding Y, Vaziri ND, Gonick HC. Lead induced hypertension: Response to sequential infusions of L-arginine, superoxide dismutase and nitroprusside. Environ Res. 1998;76:107–13. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1997.3796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp DS, Osterloh J, Becker CE, Bernard B, Smith AH, Fisher JM, et al. Blood pressure and blood lead concentration in bus drivers. Environ Health Perspect. 1988;78:131–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8878131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowack R, Wiecek A, Exner B, Gretz N, Ritz E. Chronic lead exposure in rats: Effects on blood pressure. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:433–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasperczyk S, Birkner E, Kasperczyk A, Zalejska J. Activity of superoxide dismutase and catalase in people protractedly exposed to lead compounds. J Ann Agric Environ Med. 2004;11:291–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaziri ND, Ding Y, Ni Z, Gonick HC. Altered nitric oxide metabolism and increased oxygen free radical activity in lead-induced hypertension: effect of lazaroid therapy. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1042–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heydari A, Norouzzadeh A, Khoshbaten A, Asgari A, Ghasemi A, Najafi S, et al. Effects of short-term and subchronic lead poisoning on nitric oxide metabolites and vascular responsiveness in rat. Toxicol lett. 2006;166:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharifi AM, Darabi R, Akbarloo N, Larijani B, Khoshbaten A. Investigation of circulatory and tissue ACE activity during development of lead-induced hypertension. Toxicol Lett. 2004;153:233–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]