Abstract

Complete 1H, 13C, 19F and11B NMR spectral data for 28 potassium organotrifluoroborates are described. The resonance for the carbon bearing the boron atom is described for most of the studied compounds. A modified 11B NMR pulse sequence was used and better resolution was observed allowing the observation of 11B–19F coupling constants for some of the studied compounds.

Keywords: 1D NMR, 19F NMR, 11B NMR, potassium organotrifluoroborates

Introduction

Since the discovery of the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction,[1] organoboron have become important reagents in transition-metal-catalyzed reactions, particularly in palladium-catalyzed reactions, producing new carbon–carbon bonds. The large number of applications of tricoordinate boron compounds, particularly boronic acids and esters, can also be explained by the fact that these compounds are easily synthesized via transmetalation or hydroboration reactions.[2]

Organotrifluoroborates have proven to be a good option to replace boronic acids and boronate esters providing advantages over the latter reagents in many Suzuki type coupling reactions,[3] 1,2-[4] and 1,4-additons[5] to carbonyl compounds, Mannich type reactions,[6] synthesis of alcohols,[7] amines,[8] and iodides,[9] and Heck type reactions,[10] among other transformations.[11] (For an extensive review about synthesis and applications of organotrifluoroborate salts see Ref. [11].)

One of the major benefits is the ability to elaborate upon the structure of a simple, functionalized organotrifluoroborate, increasing its molecular complexity while maintaining the valuable carbon–boron bond for subsequent transformation. Organotrifluoroborates may also act as serine protease inhibitors[12] and, more recently, the pharmacological and toxicological properties of potassium thiophene-3-trifluoroborate were investigated.[13]

This paper describes the complete spectral reference data of 28 potassium organotrifluoroborates, including hetero-nuclei analysis of 11B and 19F. The selected list of organotrifluoroborates includes compounds with different functional groups and structures that allowed an analysis of the neighboring influence in the hetero-nuclei shifts. The structural and spectroscopic assignments were also made through the combined use of 1D and heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments.

Results and Discussion

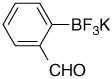

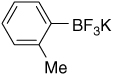

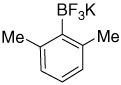

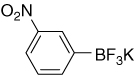

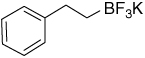

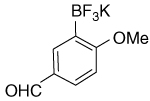

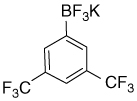

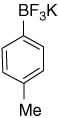

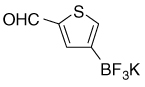

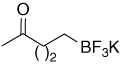

Compounds 1,[14] 2,[15] 3–4,[16] 27,[17] and 28[18] were prepared according to literature procedures. The potassium organotrifluoroborates 5–26 were prepared from the corresponding boronic acids using KHF2 in MeOH: H2O in good yields[19] and submitted to 1H, 13C, 11B, and 19F NMR analyses.

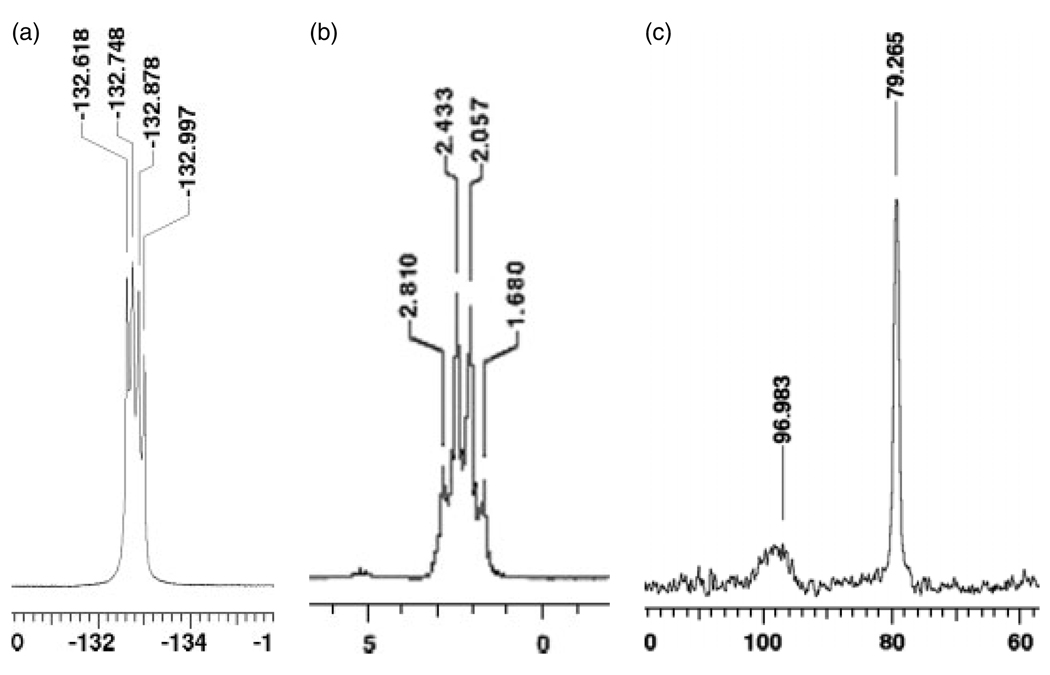

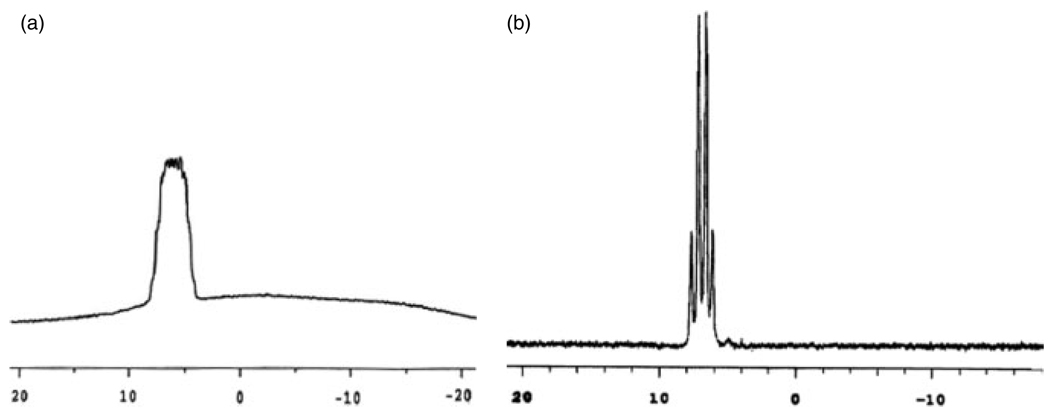

In some of the studied compounds the J (11B–19F) in the 11B NMR spectra and J (19F–11B) in the 19F NMR spectra were observed (Fig. 1a and b). The relative rapid 11B relaxation often hinders or excludes the observation of 11B coupling constants J (11B–X) in spectra of both 11B and other nuclei by line broadening.[20] A modified 11B NMR pulse sequence was used and better resolution was observed, allowing the observation of 11B–19F coupling constants for some compounds. A comparison between the spectrum obtained using standard acquisition parameters (Fig. 2a) and the spectrum obtained using a different pulse sequence (Fig. 2b) is shown in Fig. 2. Because of the better resolution on the spectrum, it was possible to observe the coupling constant more clearly.

Figure 1.

NMR spectra of compound 1, parts (a) 19F NMR spectrum (282 MHz, DMSO-d6) showing the 19F–11B coupling; (b) 11B NMR spectrum (96 MHz, DMSO-d6) showing the 11B–19F coupling; (c) 13C NMR spectrum (75 MHz, DMSO-d6) showing the resonance from the carbon bearing the boron nuclei (broad).

Figure 2.

(a) 11B NMR (128 MHz, DMSO-d6) spectra of 28 using standard acquisition parameters and; (b) 11B NMR (96 MHz, DMSO-d6) using a different pulse sequence.

Considering that nuclear spins of 11B and 19F nuclei are equal to 3/2 and 1/2, respectively and that the lines number on the spectrum is determined by the term 2nI+1, where I is the nuclear spin value and n is number of neighbor nucleus, the spectra show different lines due to scalar coupling. 19F NMR spectrum of compound 1 (Fig. 1a) shows four lines of approximately the same intensity (1 : 1 : 1 : 1) because there is only one nucleus of 11B coupling with the 19F nucleus; in the Fig. 1b, it is possible to observe a quartet (1 : 3 : 3 : 1) due to scalar coupling with three 19F nucleus. The resonances corresponding to the carbon bearing the boron atom were observed to be broad due to the quadrupolar relaxation mechanism of 11B nucleus. This effect can be observed in Fig. 1cwhere the 13C spectrum shows two signals being the signal at δ96.98 ppm broad because of the quadrupole moment of 11B nuclei. Notably, this resonance is not described for potassium organotrifluoroborates.[21]

By using line-narrowing techniques or less viscous solvents and/or higher temperatures it is possible to improve the resolution. As predicted, different coupling constants values were observed in both 11B and 19F spectra of potassium ethynyltrifluoroborate at 25 °C when the solvent was changed (Table 1). In the expectation that the relation between the variation of magnitude of J with temperature, we also obtained the spectra of potassium ethynyltrifluoroborate at 25 °C, and 50 °C in different solvents. The temperature dependence of the coupling constants is also given in Table 1. The chemical shifts practically do not change with temperature.

Table 1.

Effect of solvent and temperature on the 11B and 19F chemical shifts and coupling constants for 1

| Compound | Solvent | Temp. (°C) |

δ11B (ppm) |

δ19F (ppm) |

J1(11B–19F) (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

D2O | 25 | 2.62 | −144.2 | 15.1 |

| 1 | |||||

| D2O | 50 | 2.86 | −143.8 | 14.6 | |

| Acetone-d6 | 25 | 2.96 | −135.8 | 32.8 | |

| Acetone-d6 | 50 | 2.97 | −136.0 | 36.2 | |

| CD3OD | 25 | 4.00 | −155.7 | 11.6 | |

| CD3OD | 50 | 4.03 | −155.7 | 11.5 | |

| CD3CN | 25 | 2.89 | −135.7 | 35.9 | |

| CD3CN | 50 | 2.92 | −135.8 | 35.9 | |

| DMSO-d6 | 25 | 2.20 | −132.8 | 36.6 | |

| DMSO-d6 | 50 | 2.23 | −132.9 | 36.1 |

Good resolution was obtained for the 19F spectra of potassium organotrifluoroborates. The 19F nucleus has a zero quadrupolar moment, it is only 20% less sensitive than 1H, and has a high sensitivity because of a high-magnetogyric ratio.[22] These factors support the idea that 19F nucleus is the appropriate choice to analyze potassium organotrifluoroborates by NMR.

The chemical shifts in the 19F spectrum generally decrease from a neutral molecule to an anion. In this way, it would be expected the more fluorines attached to any given atom, the less shielded would be the 19F nucleus.[23] This effect was also observed for the studied organotrifluoroborates where the fluorines attached to the boron atom presented chemical shifts in the range of −129 to −141 ppm (Table 2).

Table 2.

1H, 13C, 11B, and 19F chemical shifts of selected potassium organotrifluoroborates

| Compound | δ(1H) (ppm) | δ(13C) (ppm) | δ(11B (ppm) | δ(19F (ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.93 (s, 1H) | 97.6 (br); 79.1 | 2.20 (J = 36.6 Hz) | −132.8 | |

| 2 | 5.84–5.69 (m, 1H); 5.22–2.13 (m, 2H) |

146.2(br); 121.6 | 6.87 (J = 51 Hz) | −139.5 | |

| 3 | 7.28–7.25 (m, 5H) | 130.9; 128.3; 126.9; 125.4; 104.3 (br); 89.5 |

2.92 (J = 19 Hz) | −132.0 | |

| 4 | 1.97 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H); 1.34–1.29 (m, 4H); 0.83 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H) |

90.8; 56.9; 31.5; 22.0; 18.7; 14.0 |

2.65 | −131.5 | |

| 5 | 7.43 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H); 7.19–7.10 (m, 3H) |

149.1(br); 131.6; 126.8; 125.8 | 7.94 | −139.3 | |

| 6 |  |

– | 147.9 (d, J = 247 Hz); 139.0 (d, J = 240 Hz); 136.6 (d, J = 247 Hz); 119.1 (br) |

6.01 (J = 42 Hz) | −132.8; (−135.0)–(−135.1) (m); −160.7 (t, J = 19 Hz); (−165.3)–(−165.7) (m) |

| 7 | 7.73 (d, J = 7.8Hz, 2H); 7.49 (d, J = 7.8Hz, 2H); 2.51 (s, 3H) |

157.9; 141.5(br); 132.8; 112.6; 55.1 |

7.39 | −140.1 | |

| 8 | 7.58–7.50 (m, 2H); 7.43–7.35 (m, 2H) |

155.9 (br); 132.0; 126.2 (qua, J = 30 Hz); 125.2 (qua, J = 272 Hz); 122.8 |

7.44 | −135.4; −140.2 | |

| 9 | 9.90 (s, 1H); 7.66 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 2H); 7.55 (d, J = 7.5Hz, 2H) |

193.3; 159.5(br); 133.8; 131.6; 127.7 |

7.12 | −140.2 | |

| 10 |  |

9.95 (s, 1H); 7.89 (s, 1H); 7,68 (ddd, J3 = 7.5Hz, Hz, J4 = 1.5, 1H); 7,61 (ddd, J3 = 7.5 Hz, J4 = 1.5, 1H); 7,34 (dd, J3 = 7.5 Hz, 1H) |

195.0; 150.3 (br); 138.4; 135.1; 133.4; 127.7; 127.2 |

7.44 | −139.9 |

| 11 |  |

10.45 (s, 1H); 7.69 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H); 7.63 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H); 7.40 (dd, J = 7.5 Hz, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H); 7.24 (dd, J = 7.2 Hz, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H) |

197.1; 156.0 (br); 139.2; 132.9; 132.1; 126.0; 124.6 |

7.59 (J = 51 Hz) | −132.5 |

| 12 |  |

7.30 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H); 6.85–6.87 (m, 3H); 2.27 (s, 3H) |

148.9 (br); 140.5; 131.6; 128.2; 125.1; 123.4; 21.7 |

7.74 (J = 52 Hz) | −137.7 |

| 13 |  |

6.81–6.76 (m, 1H); 6.69 (d, J = 7.2 Hz; 2H); 2.31 (s, 6H) |

141.0; 126.6; 126.0 (br); 124.7; 23.4 |

8.23 (J = 53 Hz) | −129.6 |

| 14 | 7.40–7.36 (m, 2H); 6.93–6.87 (m, 2H) |

161.7 (d, J1 = 240Hz); 145.2 (br); 133.4; 113.5 (d, J2 = 15 Hz) |

7.77 | −118.6; −139.1 | |

| 15 |  |

8.18 (s, 1H); 7,96 (dd, J3 = 8.1 Hz, J4 = 2.0 Hz, 1H); 7,80 (dd, J = 7,2 Hz, J4 = 2.0 Hz, 1H); 7,43 (dd, J3 = 7.8 Hz, J3 = 7,2 Hz, 1H) |

152.4 (br); 147.4; 138.7; 128.5; 125.7; 121.1 |

7.24 | −140.5 |

| 16 |  |

7.16–7.06 (m, 1H); 6.69 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H) |

166.1 (dd, J1 = 240 Hz, J3 = 17 Hz); 128.0; 121.3 (br); 110,3 (d, J2 = 29 Hz) |

6.57 (J = 45 Hz) | −103.0; −132.5 |

| 17 |  |

7.21–7.02 (m, 5H); 2.48–2.42 (m, 2H); 0.40–0.28 (m, 2H) |

148.0; 127.9; 127.7; 124.5; 32.1; 22.3 (br) |

5.19 (J = 18 Hz) | −138.3 |

| 18 |  |

9.78 (s, 1H); 7.87 (d, J4 = 2.5 Hz, 1H); 7.66 (dd, J3 = 8.7 Hz, J4 = 2.5 Hz,1H); 6.91 (d, J3 = 8.7 Hz, 1H); 3.74 (s, 3H) |

192.2; 168.1; 137.8 (br); 135.1; 131.0; 128.5; 109.6; 55.1 |

7.23 | −138.2 |

| 19 |  |

7.88 (s, 2H); 7.72 (s, 1H) | 131.3; 128.2(br); 126.0; 122.4; 118.8 |

6.94 | −61.7; −141.2 |

| 20 |  |

7.22 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); 6.91 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H); 2.21 (s, 3H) |

146.0 (br); 133.6; 131.5; 127.2; 21.2 |

7.88 | −138.8 |

| 21 | 9.87 (s, 1H); 7.84 (s, 1H); 7.64 (s, 1H) |

185.3; 153.7 (br); 144.0; 143.1; 136.9 |

6.41 | −136.8 | |

| 22 |  |

9.86 (s, 1H); 7.85 (s, 1H); 7.65 (s, 1H) |

185.1; 153.6 (br); 143.9; 143.0; 136.7 |

6.60 | −136.9 |

| 23 | 8.54 (s, 1H); 8.29 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H); 7.67 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H); 7.12 (dd, J3 = 9.0, J3 = 4.8, 1H) |

152.6; 147.0; 142.2 (br); 139.6; 123.2. |

7.66 | −139.4 | |

| 24 | 7.23 (dd, J3 = 3.9, J3 = 3.8, 1H); 6.93 (dd, J3 = 3.8, J4 = 1.2, 1H); 6.87 (br) |

150.6 (br); 127.5; 126.9; 124.4 | 6.87 (J = 46 Hz) | −134.1 | |

| 25 | 7.22 (d, J3 = 3.0 Hz, 1H); 7.10 (s, 1H); 7.06 (d, J3 = 3.0 Hz, 1H) |

151.3 (br); 132.0; 124.7; 123.0 | 7.20 | −135.8 | |

| 26 | (−0.02)–(−0.151) (m,4H); (−0.71)–(−0.84) (m, 1H) |

1.2; −0,4(br) | 8.77 | −141.2 | |

| 27 |  |

2.28 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 2.03 (s, 3H); 1.37 (qui, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 1.07 (qui, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); −0.06 (m, 2H) |

210.8; 43.9; 30.0; 27.7; 25.5 | 9.36 | −137.2 |

| 28 | 1.80 (s, 2H). | * | 6.85 (J = 50 Hz) | −140.7 |

No peak was observed for this compound.

It was also known that the J (19F–11B) varies by changing the solvent.[24] In fact, the observed coupling constants for 1 in protic solvents were significantly smaller than the ones observed in nonprotic solvents. The coupling constants did not appear to be dependent on the temperature on the analyzed compound (Table 1).[25]

In spite of being salts, potassium organotrifluoroborates are slightly soluble in water, with some exceptions. Generally these compounds show high solubility in polar solvents such as methanol, acetonitrile, acetone, dimethylfumarate (DMF), and dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). It is also known from literature that electron-donating groups enhance the rate of hydrolysis of these compounds into the corresponding boronic acids.[26] These factors together with the small changes in the coupling constants and chemical shifts (Table 1), make DMSO-d6 the appropriate choice for the analysis of potassium organotrifluoroborates.

Experimental

Standard bench top techniques were employed for handling air-sensitive reagents. tetrahydrofuran (THF) was distilled from Na/benzophenone ketyl. Methanol was distilled from magnesium methoxide. Distilled H2O was degassed by sparging with Ar(g) for >30 min. All other solvents were high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC)grade and used as received. Boronic acids 5 and 6 were purchased from Aldrich Chemical Company. Boronic acids 7–26 were purchased from Frontier Chemicals and used as received. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (CIL).

Potassium ethynyltrifluoroborate (1)

To a solution of ethynylmagnesium bromide in THF (10.0 mmol, 20 ml of a 0.5 m THF solution) trimethyl borate was added (1.59 g, 15.3 mmol) at −78 °C. The solution was stirred for 1 h at this temperature, and then warmed up to −20 °C and stirred for an additional hour. To the resultant white suspension a solution of KHF2 was added (4.71 g, 60.3 mmol) in water (15 ml) and the solution was stirred at this temperature for 1 h and at room temperature for 1 h. The obtained reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was dissolved in hot acetone. The residue was removed by filtration and the filtrate was concentrated to yield 1.05 g (80%) of the title compound as a white solid (mp 210–212 °C decomp.).

Potassium vinyltrifluoroborate (2)

To a solution of trimethyl borate (3.4 ml, 30 mmol) in THF (20 ml) at −78 °C under argon was added dropwise vinyl magnesium bromide (20 ml, 20 mmol of a 1 m solution in THF). The mixture was stirred for 0.5 h at this temperature and at room temperature for 0.5 h. KHF2 (9.4 g, 120 mmol) was added in one portion at 0 °C followed by water (20 ml). The resulting suspension was stirred for 0.5 h at room temperature, and the solvents were removed and the resulting white solid was dried under high vacuum for 2 h. The solid was then washed with acetone and with hot acetone. The resulting organic solution was filtered, and the solvent was removed to yield a white solid, which was dissolved in hot acetone and precipitated with diethyl ether to yield 2.20 g (80%) of the title compound as a white solid.

Potassium alkynyltrifluoroborates (3 and 4)

To a solution of the appropriate alkyne (10 mmol, 1 equiv) in THF (20 ml) at −78 °C under argon dropwise n-BuLi (6.25 ml, 1.6 m in hexane, 10 mmol, 1 equiv) was added. The solution was stirred for 1 h at this temperature, then trimethyl borate (1.56 g, 15 mmol, 1.5 equiv) was added dropwise. The solution was stirred at −78 °C for 1.5h and allowed to warm to −20 °C. A saturated aqueous solution of KHF2 (4.7 g, 60 mmol, 6.0 equiv) was added to the vigorously stirred solution. The resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h at −20 °C and at room temperature for 1 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the resulting white solid was dried under high vacuum for 2 h. The solid was then washed with acetone and with hot acetone. The resulting organic solution was filtered, and the solvent was removed to yield a white solid, which was dissolved in hot acetone and precipitated with diethyl ether. Potassium phenylethynyltrifluoroborate (3) 1.41 g (68%); potassium hex-1-ynyltrifluoroborate (4) 1.39 g (74%).

General procedure for preparation of potassium organotrifluoroborates (5–26)

To the boronic acid (5 mmol) in MeOH (10 ml) a solution of KHF2 was added dropwise (1.56 g, 20 mmol) in H2O (8 ml) using an addition funnel. The mixture was stirred for 30 min and concentrated under high vacuum. The residual solids were extracted with four portions of 20% MeOH in acetone. The combined extracts were concentrated close to the saturation point and Et2O was added until no more precipitation was observed. The solids were collected, washed with two portions of Et2O, and dried under high vacuum to give the corresponding products. Potassium phenyltrifluoroborate (5) 0.73 g, 80%; potassium perfluorotrifluoroborate (6) 0.82 g (60%); potassium 4-methoxyphenyltrifluoroborate (7) 0.92 g (82%); potassium 4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyltrifluoroborate (8) 1.00 g (80%); potassium 4-formyl-phenyltrifluoroborate (9) 0.97 g (92%); potassium 3-formyl-phenyltrifluoroborate (10) 0.95 g (90%); potassium 2-formyl-phenyltrifluoroborate (11) 0.90 g (85%); potassium o-tolyl-trifluoroborate (12) 0.84 g (85%); potassium 2,6-dimethyltrifluoroborate (13) 0.84 g (80%); potassium 4-fluoro-phenyltrifluoroborate (14) 0.80 g (80%); potassium 3-nitro-phenyltrifluoroborate (15) 0.93 g (82%); potassium 2,6-difluorophenyltrifluoroborate (16) 0.93 g (85%); potassium phenylethyltrifluoroborate (17) 0.85 g (81%); potassium 5-formyl-2-methoxyphenyltrifluoroborate (18) 1.08 g (90%); potassium 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyltrifluoroborate (19) 1.36 g (85%); potassium p-tolyl-trifluoroborate (20) 0.79 g (80%); potassium 5-formylthiophen-2-yl-trifluoroborate (21) 0.89 g (82%); potassium 5-formylthiophen-3-yl-trifluoroborate (22) 0.87 g (80%); potassium pyridin-3-yltrifluoroborate (23) 0.76 g (83%); potassium 2-thienyltrifluoroborate (24) 0.77 g (82%); potassium 3-thienyltrifluoroborate (25) 0.80 g (85%); potassium cyclopropyl trifloroborate (26) 0.59 g (80%);

Potassium 4-oxopentyltrifluoroborate (27)

To a solution of potassium 4-methylpent-4-enyltrifluoroborate [H2C=C(CH3)CH2CH2CH2BF3K] (0.202 g, 1.28 mmol) in an acetone/H2O mixture (30% H2O in acetone, 14 ml) at −70 °C was applied a flow of ozone for 14 min. The solution was then degassed with N2 for 15 min followed by the addition of H2O (2ml). This was allowed to warm to r.t. while stirring. Following solvent removal, the resulting white solid was purified by dissolving in hot acetone and precipitating with Et2O, affording 27 (0.14 g, 70%) as a white solid.

Potassium iodomethyltrifluoroborate (28)

To a solution of potassium bromomethyltrifluoroborate (2.0 g, 10 mmol) in acetone (150 ml) NaI was added (1.5 g, 10 mmol) in one portion. After stirring at 25 °C for 2 h, the suspension was filtered through a Celite pad and then the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to give the crude product, which was purified by dissolving in a minimal amount of dry acetone and precipitating with Et2O to yield a 2.38 g(96%)of the title compound as a white solid.

NMR measurements

1H (300 MHz), 13C (75MHz), 11B (96MHz), and 19F (282 MHz) NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian UNITY PLUS 300 spectrometer. Spectra were recorded in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO-d6), using DMSO residual peak as the 1H internal reference (2.5 ppm); and the central peak of DMSO-d6 at 39.5 ppm for 13C NMR. 11B NMR spectra were calibrated using BF3 Et2O (0.0 ppm) as external reference. All 19F NMR chemical shifts were referenced to external CF3CO2H (0.0 ppm).

Typical parameters were as follows: 1H NMR: Pulse angle of 45°, acquisition time of 3.6 s, 16 repetitions and, spectral width of 15 ppm. 13C NMR: Pulse angle of 90°, delay of 2.3s, acquisition time of 1.7 s, 1024 repetitions, and, spectral width of 250 ppm. 19F NMR: Pulse angle of 45°, delay of 1.0 s, acquisition time of 0.3 s, 80 repetitions, line broadening of 0.3 Hz and, a spectral width of 177 ppm. All 11B NMR spectra were obtained using a S2PUL pulse sequence (VARIAN) which consists in a first pulse of 90°, a delay of 0.5 s, and a second pulse of 180°, followed by an acquisition time of 1.0 s. The spectra were recorded as 128 repetitions, spectral width of 171 ppm, and processed with line broadening of 5 Hz. For all nuclei spectra the temperature was maintained within ± 1 °C by using a Varian temperature unit.

The parameters to obtain standard 11B NMR spectra (128 MHz) using a Bruker spectrometer were as follows: zgpg30 pulse sequence (Bruker) which consists in a single pulse sequence with p1 = 7 µs (90°) and a two level Waltz decoupling scheme with lower power during 1 s recycle delay and higher power during pulse and acquisition. The delay was 1.0 s and the spectrum was recorded using 128 repetitions, with 5 Hz line broadening and 1 Hz.

Conclusion

In this study, complete 1H, 13C, 19F, and11B NMR spectral data for 28 potassium organotrifluoroborates were described. The resonance for the carbon bearing the boron atom is described for the first time for most of the studied compounds. In addition, a modified 11B NMR pulse sequence was used and better resolution was observed, allowing the observation of 11B–19F coupling constants for some compounds.

References

- 1.Miyaura N, Yamada K, Suzuki A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979;20:3437. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Brown HC. Organic Syntheses via Boranes. Vol. 1997. Milwaukee, WI: Aldrich Chemical; vol. 1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown HC, Zaidlewicz M. Organic Syntheses via Boranes. vol. 2. Milwaukee, WI: Aldrich Chemical; 2001. [Google Scholar]; (c) Suzuki A, Brown HC. Organic Syntheses via Boranes. vol. 3. Milwaukee, WI: Aldrich Chemical; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Molander GA, Figueroa R. Aldrichim. Acta. 2005;38:49. [Google Scholar]; (b) Stefani HA, Cella R, Vieira AS. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3623. [Google Scholar]; (c) Molander GA, Ellis N. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:275. doi: 10.1021/ar050199q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thadani AN, Batey RA. Org. Lett. 2002;4:3827. doi: 10.1021/ol026619i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Ma Y, Song C, Ma C, Sun Z, Chai Q, Andrus MB. Angew.Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:5871. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Duursma A, Lefort L, Boogers JAF, de Vries AHM, de Vries JG, Minnard AJ, Feringa BL. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:1682. doi: 10.1039/b404996a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Duursma A, Boiteau J-G, Lefort L, Boogers JAF, de Vries AHM, de Vries JG, Minnard AJ, Feringa BL. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8045. doi: 10.1021/jo0487810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tremblay-Morin J-P, Raeppel S, Gaudette F. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:3471. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quach TD, Batey RA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1381. doi: 10.1021/ol034454n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quach TD, Batey RA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4397. doi: 10.1021/ol035681s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Kabalka GW, Mereddy AR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:343. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kabalka GW, Mereddy AR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:1417. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pucheault M, Darses S, Genet J-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15356. doi: 10.1021/ja044749b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darses S, Genet J-P. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:288. doi: 10.1021/cr0509758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smoum R, Rubinstein A, Srebnik M. Org. Mol. Chem. 2005;3:941. doi: 10.1039/b415957h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira RA, Savegnago L, Jesse CR, Menezes PH, Molander GA. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2009;104:448. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto Y, Hattori K, Ishii J-I, Nishiyama H. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:4294. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darses S, Michaud G, Genet J-P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999;8:1875. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paixao MW, Weber M, Braga AL, Azeredo JB, Deobald AM, Stefani HA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2366. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molander GA, Cooper DJ. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3558. doi: 10.1021/jo070130r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molander GA, Ham J. Org. Lett. 2006;8:2031. doi: 10.1021/ol060375a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Vedejs E, Chapman RW, Fields SC, Lin S, Schrimpf MR. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:3020. [Google Scholar]; (b) Molander GA, Biolatto B. Org. Lett. 2002;4:1867. doi: 10.1021/ol025845p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Molander GA, Biolatto B. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:4302. doi: 10.1021/jo0342368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Metz KR, Lam MM, Webb AG. Concepts Mag. Res. 2000;12:21. [Google Scholar]; (b) Clouse AO, Moody DC, Rietz RR, Roseberry T, Schaeffer R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2496. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vedejs E, Fields SC, Hayashi R, Hithccock SR, Powell DR, Schrimpf MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2460. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Battiste J, Newmark RA. Prog. Nuc. Magn. Res. 2006;48:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gerig JT. Prog. Nuc. Magn. Res. 1994;26:293. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrew ER. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London Ser. A. 1981;299:505. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) San Fabian J, Hoekzema AJAW. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;121:6268. doi: 10.1063/1.1785141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Emsley JW, Phillips L, Wray V. Prog. Nuc. Magn. Res. 1976;10:83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jameson CJ, Jameson AK, Parker H. J. Chem. Phys. 1978;69:1318. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ting R, Harwig CW, Lo J, Li Y, Adam MJ, Ruth TJ, Perrin DM. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:4662. doi: 10.1021/jo800681d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]