Abstract

This paper examined maternal parenting behaviors as mediators of associations between interparental violence and young children's internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Participants included 201 toddlers and their mothers. Assessments of interparental violence and children's symptoms were derived from maternal surveys. Maternal parenting behaviors were assessed during an observational paradigm and coded for hostility, responsiveness and disengagement. Results indicated that mother's responsiveness and disengagement mediated associations between interparental violence and children's internalizing (e.g., withdrawn, inhibited, anxious, depressed behaviors) and externalizing (e.g., aggressive behaviors, attentional difficulties) symptoms. The results are interpreted in the context of conceptualizations that underscore how different dimensions of maternal parenting behaviors may play key explanatory roles in understanding associations between interparental violence and children's adjustment difficulties.

Keywords: Toddlers, interparental violence, parenting, child adjustment

Exposure to interparental violence has been associated with a host of negative mental health outcomes in children and adolescents, including significant deficits in emotional, behavioral and cognitive functioning (e.g., Cummings & Davies, 2002; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenney, 2003). Furthermore, research has demonstrated that children exposed to interparental violence and aggression are affected regardless of the gender of the parent perpetrator (e.g., English, Marshall, & Stewart, 2003; Mahoney, Donnelly, Boxer, & Lewis, 2003) or the gender of the child (e.g., Kitzman, et al., 2003). Accordingly, researchers in the field have increasingly called for the incorporation of theoretically driven process models explicating possible underlying, explanatory mechanisms by which children are negatively affected by the presence of interparental violence (e.g., Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2006; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003; Levendosky, Bogat, & von Eye, 2007; Prinz & Feerick, 2003).

Towards addressing this gap, emotional security theory (EST) provides a rich, theoretical foundation for furthering our understanding of how interparental violence undermines children's functioning through its association with parenting disturbances (e.g., Davies & Cummings, 1994; Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2006). According to formulations within the theory, interparental violence increases children's vulnerability to mental health difficulties by undermining their goal of preserving a sense of security and safety in the context of the family. In outlining a mediational process by which interparental violence impacts children's adjustment, the indirect path hypothesis of EST posits that interparental violence disrupts parental abilities to provide sensitive, responsive, and consistent care to children (e.g., Davies, Harold, Goeke-Morey, & Cummings, 2002; Sturge-Apple, Davies, & Cummings, 2006). In turn, EST theorizes that this diminished caretaking erodes children's sense of security and safety in parent-child relationships which increases children's vulnerability to mental health difficulties and socio-emotional maladjustment.

Existing studies testing indirect path models linking interparental violence, parenting, and child outcomes have yielded complex and sometimes counterintuitive results. For example, Levendosky and colleagues (2003) found that interparental violence was associated with more effective parenting practices, which, in turn, were associated with greater child adjustment. In contrast, findings from other studies lend support for the mediational role of parenting disturbances in associations between interparental violence and child psychological problems (e.g., Levendosky, Leahy, Bogat, Davidson, von Eye, 2006; Margolin & John, 1997; Owen, Thompson, & Kaslow, 2006). Although this research has resulted in valuable advances in understanding the interplay between interparental violence and parenting, existing studies commonly rely on aggregation procedures that subsume multiple dimensions of parenting into a single broad parenting construct or examine single dimensions of parenting within analytic models (Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2006). Accordingly, little is known about the distinct developmental functions of specific parenting dimensions in indirect path models of interparental violence and child development (for an exception, see Rea & Rossman, 2005). To address this gap in the literature, the goal of this study is to increase the precision of indirect pathways by simultaneously examining three different dimensions of parenting in associations between interparental violence and child psychological problems. Specifically, we assessed the explanatory power of maternal hostility, responsiveness, and disengagement as mediators in associations between interparental violence and children's adjustment. Interparental violence was operationalized as a dyadic construct incorporating both self and partner's violent and aggressive behaviors in the context of the interparental relationship. Indices of children's adjustment included assessments of children's internalizing (e.g., withdrawn, inhibited, anxious, depressed behaviors) and externalizing (e.g., aggressive, antisocial behaviors) symptomatology.

The spillover hypothesis (Easterbrooks & Emde, 1988) served as the overarching conceptual framework guiding hypotheses concerning the first link in the indirect path hypothesis of EST. As the prevailing model guiding empirical research on associations between interparental conflict and parenting processes, the spillover hypothesis proposes that “the emotions, affect, and mood generated in the marital realm transfers to the parent-child relationship (Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000, p. 26).” Thus, negativity and anger in the interparental system is hypothesized to result in parent's diminished capacities for warm/responsive parenting as well as increased hostile and harsh parenting. Research documenting concurrent and longitudinal associations between marital and parent-child difficulties has generally supported the tenets of the spillover hypothesis (e.g., Engfer, 1988; Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000; Gerard, Krishnakumar, & Buehler, 2006; Sturge-Apple, Davies, & Cummings, 2006). Interestingly, a small corpus of studies have reported compensatory parenting behaviors in the context of interparental conflict (e.g., Mahoney, Boggio, & Jouriles, 1996). However, guided by previous work documenting the negative impact of interparental conflict on maternal parenting behaviors, we hypothesized that interparental violence would be associated with diminished maternal parenting behaviors across multiple parenting dimensions.

In addressing the second link of the EST indirect path hypothesis, parenting difficulties arising from interparental violence are theorized to account in part for the associations between interparental violence and children's symptomatology. EST proposes that parenting difficulties accompanying interparental violence engender child psychopathology by undermining children's felt security in the parent-child relationship (i.e., their confidence in parents as sources of protection and support) (see Davies, et al., 2002). While to our knowledge, no study has made comparisons among multiple dimensions of parenting simultaneously in associations between interparental violence and child adjustment, research has demonstrated that different dimensions of parenting serve as mediating mechanisms in associations with interparental violence and child adjustment (e.g., Rea & Rossman, 2005). Using an EST perspective as a guide, we hypothesized that the diminished maternal responsiveness, as well as increased disengagement in the context of interparental violence would be associated with heightened levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. In addition, given previous findings linking parental hostility and children's difficulties with behavioral control in the context of interparental violence, we also hypothesized that maternal hostility would serve as a mediator of associations between interparental violence and children's externalizing symptoms.

Alternative conceptualizations of the role of parenting behaviors in family process models have been posited in the literature (e.g., Frosch and Mangelsdorf, 2001). In particular, some research has suggested that parenting may serve as a moderating variable in associations between interparental difficulties and child adjustment. For example, warm, supportive, and responsive parenting behaviors in the context of interparental violence may serve as a protective factor which buffers children from the negative developmental outcomes associated with exposure to interparental hostility and violence. In contrast, hostile or disengaged caregiving practices may serve as a risk factor for children's increased vulnerability to behavior problems in the face of greater interparental conflict or violence. We know of no study that has simultaneously explored how parenting behaviors may serve as mediators or moderators in process models of interparental violence and children's adjustment, however one previous study examined the comparative strength of these two models in a study of the effects of marital conflict and children's adjustment and results supported the moderating role of parenting in process models (Frosch & Manglesdorf, 2001). Thus, in order to compare the relative viability of the indirect path hypothesis (e.g., parenting-as-mediator model) with the parenting-as-moderator model, we examined whether maternal caregiving behaviors moderated associations between interparental violence and children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Finally, our decision to examine associations between interparental violence and maternal parenting behaviors during toddlerhood was based on several considerations. From a methodological standpoint, the majority of research examining the impact of interparental violence on children has focused on early childhood to adolescence (e.g., Levendosky, Huth-Bocks, Shapiro, & Semel, 2003). This gap in the research is important when contextualized within findings from a meta-analytic study suggesting that exposure to interparental violence during the preschool years conveys increased risk for negative outcomes when compared with other age groups (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003). From a developmental standpoint, early childhood is consistently posited as a significant period of developmental plasticity in children including rapid changes in emotion regulation and emerging abilities in mobility and exploratory behavior (e.g., Edwards & Liu, 2002). In addition, parents must contend with children's fluctuating bids for support and protection against a backdrop of increasing demands for autonomy and exploration. Thus, parenting during this developmental stage is contingent upon the ability to flexibly adapt to children's developing competencies while retaining the ability to maintain control and respond responsively in the context of challenging parenting situations. As a stage salient task for parents that is challenging even under normative conditions, it may be particularly difficult task for parents who are also coping with the stress of interpartner violence.

In sum, the aim of this study was to expand tests of indirect path models outlined in EST by simultaneously delineating pathways among interparental violence, multiple dimensions of maternal parenting behaviors, and children's internalizing and externalizing symptomatology in a sample of mothers and their toddlers. Towards addressing the need for the incorporation of greater methodological rigor in the interparental violence literature on parenting process models (Prinz & Feerick, 2003), the present study utilized observational assessments of mothers' parenting behaviors obtained during interactions with their children in a laboratory setting. Much of the previous research on parenting behaviors of mothers in the context of interparental violence has relied upon maternal or child reports of parenting (see Levendosky and Graham-Bermann, 2000, Levendosky, et al., 2003, and Levendosky, et al., 2006 for notable exceptions). However, empirical work examining the validity of parent's self-reports of parenting in research with young children suggest that observer ratings of caregiving behaviors may be a more accurate index of actual parenting behaviors (e.g., Sessa, Avenevoli, Steinberg, & Morris, 2001). Furthermore, the utilization of maternal self-report assessments of interparental violence and parenting may result in inflated associations between these constructs due to shared or overlapping method variance. Thus to provide a rigorous test of our path models, we utilized a multimethod measurement battery which served to reduce shared method and information variance which may have artificially inflated path models in prior research.

Participants

Two hundred and one mother-toddler dyads from a mid-sized Northeastern city participated in the current study. The sample is part of a larger, longitudinal study investigating the relationship between interparental violence and family functioning. To achieve a relatively homogeneous sample with respect to socioeconomic status (SES), mothers were recruited for participation in the study through local agencies in contact with high-risk, low SES families such as Women Infant and Children (WIC) offices, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, and from the county family court system. To maximize variability in exposure to interpartner violence in our sample, mothers completed an abbreviated form the Physical Assault subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Using recommended CTS2 criteria, screening procedures were implemented to insure that relatively equal proportions of participating mother-child dyads were represented along three bands in the interpartner violence continuum: severe, mild to moderate, and no interparental violence. Additional inclusionary criteria required that: (a) the mother was the biological parent of the child and the primary caretaker of the child and (b) the mother, maternal partner, and child had regular contact over the past year. The final sample of mothers and children was 56% Black, 23% White, 9% Latino/Hispanic, 9% Biracial, and 3% other. Median annual family income was $18,400, with most families (i.e., 95%) receiving some form of public assistance. The participating children consisted of 108 boys and 93 girls, and their average age was 25.7 months (SD = 1.69) at the time of assessment.

Procedures

Mothers and their toddlers made three visits to the laboratory within a two-week period during which they participated in observational tasks, and mothers completed interviews and questionnaires. The observational tasks used in this study are the free-play and compliance tasks.

Free-Play

The mothers and their children participated in an observational free-play task at the laboratory for seven minutes that was videotaped for later coding. The mother and child were shown into a room containing several toys attractive to two-year olds, such as blocks, toy food, and a baby doll. Mothers were told to interact/play with their child like they would at home.

Compliance

After seven minutes, an experimenter knocked on the door to signal the end of the free play session to the mother. Mothers were then instructed to ask their child to stop playing and clean-up the toys without providing assistance. The experimenter continued to knock on the door at one-minute intervals, up to three minutes, if the child appeared to be off-task. By the third knock mothers were told that they could provide assistance to their child with picking-up the toys. The compliance portion of the task was recorded for six minutes, regardless of progress, making the entire session approximately 13 minutes.

Measures

Interparental Violence

Mothers reported on both their own and their partners use of physical aggression towards each other in the past year by completing the Physical Aggression Subscale of the Conflict and Problem-Solving Scales (CPS; Kerig, 1996). Internal consistency for the mothers' self report was .88 and their report on their partners was .87. Mothers also completed the Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) physical assault subscale as another measure of physical violence by their partner. The CTS2 is a widely-used assessment of violent behavior. Internal consistency was .92.

Parenting Behaviors

Maternal behaviors were assessed based on an observational coding system adapted from the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, 2001) and Hesse and Main's (2006) observations of frightened/frightening parenting behaviors. Ratings were assessed on nine-point Likert type scales ranging from 1 (not characteristic at all) to 9 (mainly characteristic). Three trained research assistants coded the interactions with 25% overlap for reliability.

Hostility

Maternal hostility was assessed using the negative physical intrusiveness and harsh discipline subscales. Negative physical intrusiveness was defined as physically invasive, distressing behaviors used to control or demean the child, such as hitting, yanking or grabbing the child. Negative physical intrusiveness was coded separately for the play and compliance portion of the task. Harsh discipline was coded only during the compliance task and assesses the extent to which mother's disciplinary tactics were punitive or severe. Examples of harsh discipline would include screaming at, slapping, or belittling their child as a result of a violation of parental standards. Interrater reliabilities for the three hostility codes ranged from .96 to .97.

Disengagement

Maternal disengagement was measured through subscales for passive disengagement and intrusiveness, reverse scored. Passive disengagement assessed the extent to which mothers displayed passive behaviors that put physical or emotional distance between the parent and child. Examples include ignoring the child, choosing not to participate in play with the child, or showing a lethargic, apathetic attitude toward the child. Passive disengagement was coded separately for the free play and compliance tasks. Intrusiveness measured the extent to which the parent was over controlling with the child or not allowing any room for the child's independent play or exploration. Examples of intrusive behavior include taking toys out of the child's hand while they are still playing, instructing the child how to play, or excessive hovering over the child. Because a certain level of maternal intrusiveness was expected for the compliance task, intrusiveness was only coded during the free play and was later reverse-scored. Interrater reliabilities ranged from .84 to .89 for the three disengagement codes.

Responsiveness

Maternal responsiveness was assessed using warmth/support and insensitive/parent centeredness subscales. Both scales were assessed separately for the free play and compliance tasks. Warmth was measured by the maternal behaviors that indicated care or support toward the child. Examples include giving praise, smiling or laughing, and showing physical affection. Parent centeredness assessed the extent to which the mother was unaware or uncaring of the needs or abilities of her child, and consistently put her own preferences ahead of her child's. Examples include structuring the activity to reflect the parent's interests, demonstrating a lack of awareness of age-appropriate play or compliance abilities, or misinterpreting or devaluing the child's affect. Parent centeredness was reverse scored. Interrater reliabilities for the four responsiveness codes ranged from .86 to .94.

Child Behavior Problems

Mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/1 ½-5; Achenbach, 2000) for their children while at the laboratory. This version of the widely-used assessment is appropriate for use with young children between the ages of 1 ½ and 5 years. The broadband internalizing symptoms measure consisted of an aggregation of the anxiety/depression, withdrawn, somatic problems, and emotion reactivity subscales, whereas the sum of the aggressive behavior and attention problems subscales were used as an index of broadband externalizing symptoms. Internal consistency for the internalizing and externalizing scales was .83 and .92, respectively.

Results

For descriptive purposes, Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among the measures of interparental violence, the three forms of maternal parenting, and children's internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Given the presence of significant skew in the interparental violence and maternal hostility variables, these four variables were transformed using logarithmic transformations until skew was reduced to non-significance. Transformed variables were used in model analyses.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the primary variables in the study

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interparental Violence | ||||||||

| 1. CTS Physical Assault | -- | |||||||

| 2. Partner's CPS Physical | .53** | -- | ||||||

| 3. Mother's CPS Physical | .59** | .71** | -- | |||||

| Maternal Parenting | ||||||||

| 4. Disengaged | .14 | .21** | .17* | -- | ||||

| 5. Hostile | .12 | .16* | .23** | .18* | -- | |||

| 6. Responsiveness | −.18* | −.13 | −.20** | −.08 | −.51** | -- | ||

| Child Adjustment | ||||||||

| 7. Internalizing | .13 | .15* | .14* | .04 | .18* | −.31** | -- | |

| 8. Externalizing | .11 | .14* | .14* | .21** | .26** | −.27** | .62** | -- |

| M | 2.71 | 2.55 | 2.37 | 4.10 | 1.78 | 5.13 | 9.40 | 15.63 |

| SD | 4.22 | 3.99 | 3.64 | 1.49 | 1.23 | 1.70 | 6.26 | 8.99 |

Model Testing Procedures

To examine our process model, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques for testing relationships among latent and manifest constructs. This methodology allows for simultaneous assessment and comparison of multiple outcome variables and produces evidence of model fit and misspecification. In the present study, path models were estimated using the full-information maximum likelihood method (FIML) through the AMOS 7.0 statistical software (Arbuckle, 2006). The fit of our path models was assessed using the (a) chi-square statistics, (b) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values of .08 or less reflecting reasonable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and (c) the CFI statistic with values between .95 and 1.00 indicating acceptable fit (Bentler, 1990). Given the potential moderating role of child gender in indirect effects models of interparental violence and children's adjustment (Davies & Lindsay, 2001), we also examined whether any of the proposed mediational pathways differed as a function of child gender. To test the moderating role of gender, we split the data by boys and girls and estimated models simultaneously using a multiple-group analysis (for details on this approach, see Sturge-Apple, Davies, Boker, & Cummings, 2004). First, we examined the multiple group model with mediational paths between interparental violence, each parenting variable, and each specific child outcome variable constrained to be equal across gender. Next, we estimated a model in which parameters were allowed to freely vary. Model comparisons revealed no significant difference in fit for each of the models, thereby indicating that child gender did not moderate the proposed pathways. Thus the full model was examined in model analyses.

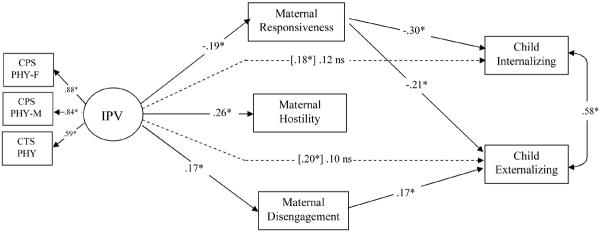

In accordance with a process-oriented perspective for testing mediational models first outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986), who suggest that mediating analyses must first establish direct associations between a predictor and outcome variables, our first analytic step was to explore whether interparental violence was directly associated with children's internalizing and externalizing symptomatology prior to estimating paths between the our proposed mediators and children's adjustment. Thus, the model in Figure 1 was estimated while constraining paths between interparental violence and maternal parenting practices to 0. The bracketed path coefficients in Figure 1 denote the resulting parameter estimates in the model. Interparental violence was significantly associated with higher levels of both externalizing (R2 = .04) and internalizing (R2 = .03) symptomatology in children.

Figure 1.

A structural equation model testing forms of maternal parenting behaviors as mediators in associations between interparental violence and child adjustment. Parameter estimates for the structural paths are standardized path coefficients. * p < .05.

Given the documented paths between interparental violence and children's symptomatology, we next examined the mediational model depicted in Figure 1. The model fit the data well, χ2 (10, N = 201) = 10.06 and p = .43, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .00. All possible mediational paths were estimated in the model, but only significant paths are depicted in the figure for clarity of presentation. The results indicated that interparental violence was associated with increased maternal hostility and disengagement and lowered maternal responsiveness. Maternal responsiveness, in turn, was associated with both lower internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, while maternal disengagement was primarily associated with higher externalizing symptomatology. Maternal hostility was originally associated with higher externalizing (β = .17, p < .001) and internalizing symptomatology (β = .14, p < .001). However, these pathways were reduced to non-significance with the inclusion of maternal responsiveness and disengagement in the model. Finally, mediation was demonstrated as pathways between interparental violence and children's symptomatology were reduced to non-significance with the inclusion of pathways between maternal parenting variables in the model. As a further test of the mediational role of maternal responsiveness and disengagement, we conducted follow up analyses of the indirect pathways using MacKinnon et al. (2007) procedures for calculating the significance of indirect effects via the Prodclin software package. Results indicated that the all three indirect pathways were significant, including: (a) interparental violence, responsiveness, and internalizing symptomatology, z' = 2.18, p < .05; (b) interparental violence, responsiveness, and externalizing symptomatology, z' = 1.67, p < .05; and (c) interparental violence, disengagement, and externalizing symptomatology, z' = 1.79, p < .05. Furthermore, maternal parenting variables explained 10% of the variance in children's externalizing symptomatology and 7% of the variance in internalizing symptomatology.

Finally, to explore whether maternal parenting behaviors served as potentiators or protective factors in the relationships between interparental violence and children's symptomatology, we ran a series of multiple regression analyses to assess whether maternal parenting behaviors moderated the association between interparental violence and children's adjustment. All predictor variables were simultaneously entered into the regression equations with mother reports of children's externalizing and internalizing symptoms as the dependent variables in the two separate multiple regression analyses. Predictor variables were centered at their respective means. Results indicated that none of the interaction terms were significant, suggesting that maternal parenting behaviors did not serve as risk or protective factors in explaining associations between interparental violence and children's adjustment.

Discussion

Exposure to domestic violence is a pervasive phenomenon in the lives of children. Recent estimates suggest that approximately one-third of children living in dual-parent homes in the United States have been exposed to violence between their parents (McDonald, Jouriles, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, Green, 2006). Furthermore, violence exposure is significantly associated with children's adjustment difficulties across a wide array of outcomes and domains (e.g., Kitzmann, et al., 2003). Attesting to the detrimental impact of exposure to violence and hostility between parents, the present study revealed that interparental violence was associated with higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptomatology in a community sample of two-year old children. Furthermore, in line with suppositions from the spillover hypothesis, interparental violence was associated with all three domains of maternal parenting behaviors including decreased responsiveness as well as increased hostility and disengagement. Finally, supporting indirect path models derived from EST, mediational analyses further indicated that in the context of interparental violence, maternal responsiveness and disengagement were mediators of the relationship between interparental violence and children's symptomatology.

The first link of our process model supported spillover conceptualizations through delineating that interparental violence was associated with all three forms of maternal parenting behaviors including diminished responsiveness and heightened disengaged and hostile parenting. Although these findings may not be surprising in the context of previous empirical work reporting the detrimental impact of interparental violence on parenting behaviors, they are illuminating when considered within the context of research suggesting stronger relationships between interpartner violence and physical, harsh and aggressive parenting behaviors compared to other parenting behaviors (e.g., Straus & Gelles, 1990). In the present study, comparisons among the relative strength of the path coefficients between interparental violence and the three parenting behaviors were equivalent, suggesting that impact of interparental violence upon different forms of parenting behaviors is similar in magnitude in our sample of mothers and their 2-year old children. This conclusion is further bolstered given that the indicators of interparental violence and parenting in the present study were based upon different methods (i.e., questionnaire, observations) and informants (maternal reports, observer ratings) which limits inflated associations due to shared method variance between these constructs.

In attempting to understand why interparental violence has a detrimental effect on maternal caregiving behaviors, affective organization models of parenting (e.g., Dix, 1991) propose that cumulative experiences with anger arousal in relationships marked by physical aggression and violence may prime mothers' negative appraisals and attributions of child behavior resulting in more hostile parenting behaviors. In addition, the necessity of maintaining elevated levels of attention and arousal in response to the constant threat of aggression and violence may disrupt mothers' ability to sensitively identify and respond to the needs of their children. Another possible interpretation is that the associations between interparental violence and diminished parenting result from a common underlying personality style characterized by high levels of aggression and hostility or have poor relational style in general (e.g., Belsky & Barends, 2002). If these findings are replicated, they call for the expansion of parenting domains considered in process models assessing family dynamics in the context of interparental violence, and stress the importance of considering multiple dimensions of parenting behaviors in interventions with families experiencing elevated levels of interparental violence.

In the second link of our process model, differential associations between maternal responsiveness and disengagement and children's symptomatology were evident. Diminished maternal responsiveness in the context of interparental violence was associated with children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms. These results support hypotheses drawn from EST which propose that the diminished capacity for responsive parenting in the context of interparental difficulties is theorized to increase children's risk for adjustment problems by weakening children's representations of the parent-child relationship as a source of security, protection and support. Furthermore, children's developing emotion regulation and coping patterns in the context of parental unresponsiveness and insensitivity may set in motion multiple processes within a child (e.g., affective-motivational, social information processing) that ultimately serve as more proximal precursors of psychopathology (e.g., Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000).

The differential effects for maternal disengagement in associations with children's externalizing symptomatology compared with internalizing symptomatology are of additional interest. In interpreting this finding within ethological formulations of EST, it may be that the lack of maternal involvement or conversely the presence of maternal passivity with respect to childrearing may result in a lack of structure or power in the parent-child relationship as mothers abdicate parental control and guidance over children. Collapse in the hierarchical structure of the parent-child relationship may in turn amplify children's dispositions to use dominant and aggressive strategies to help regulate exposure and cope with family stress and violence (e.g. Davies & Sturge-Apple, 2007).

Finally, while associations between maternal hostility and children's externalizing symptomatology were initially present, this relationship was attenuated in the context of maternal responsiveness and engagement. Thus, while strong bivariate relationships between parental hostility and children's difficulties in regulating hostile and aggressive behavior may exist, our analyses demonstrate that diminished parental warmth, responsiveness and sensitivity may override these associations. These results suggest that children's emulation or mimicking of hostility and aggressive behaviors may not be the operative process in the association between interparental violence and child externalizing symptoms. Rather models of maternal responsiveness and sensitivity as key components in the development of children's coping and regulation capacities, such as those proposed by EST and attachment theory (Ainsworth, 1979) may play a primary role in explaining children's adjustment difficulties in violent homes. Given that this is one of the first studies to simultaneously chart associations between different parenting behaviors and children's adjustment in the context of interparental violence, these conclusions are speculative and caution in interpreting effects is warranted until study findings are replicated. However, even with this cautionary note, the findings here again speak to the importance of incorporating multiple dimensions of parenting in process models of interparental violence and children's adjustment.

The findings of the present study must also be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, because fathers were not assessed in the parent study, we were not able to examine the mediational role of father's parenting practices in associations between interparental violence and children's adjustment. Given previous work demonstrating the impact of interparental violence on father-child relationships (e.g., Mahoney, et al., 2003), it will be important for future research examining indirect effects models to include samples of fathers experiencing interparental violence in order to more fully explicate how associations between parenting and child adjustment in the context of interparental violence may look similar or different for mothers and fathers. Second, the cross-sectional design cannot definitely address the temporal ordering of relationships in our process model. For example, our results do not rule out the plausible hypothesis that children's symptomatology may mediate links between interparental violence and mother's ability to provide responsive and supportive parenting. In addition, our conclusions regarding the mediational role of maternal parenting behaviors would be bolstered through examining the model processes over time whereby the predictor variable is associated with change in both the mediational and outcome variables of interest. Third, the present study did not examine possible underlying mechanisms of the associations explored in our process model. Future progress on parenting process models in the context of interparental violence hinges upon identifying mechanisms by which interparental violence negatively impacts diminished parenting and children's maladjustment. For example, recent work has charted the implications of physiological arousal in the context of interpartner conflict for parenting behaviors (e.g., Sturge-Apple, Davies, & Cummings, 2009), while others have examined the role of maternal attributions in mothers' parenting behaviors in families experiencing marital violence (e.g., Holden, Stein, Ritchie, Harris, & Jouriles, 1998). Furthermore, exposure to various parenting difficulties may set in motion multiple processes within children (e.g., affective-motivational, social learning, social information processing) that ultimately serve as more proximal causes of their psychopathology (Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Finally, caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings beyond the characteristics of our sample. Future research detailing how these proposed family pathways might be similar or different across demographic characteristics would increase our understanding as to how these processes may differ as a function of race or ethnicity.

Despite these limitations, our multi-method study represents one of the first attempts to simultaneously identify pathways among interparental violence and multiple dimensions of maternal parenting and children's symptomatology. In accordance with indirect path models outlined within emotional security theory, our results supported a model in which interparental violence was associated with children's internalizing and externalizing symptomatology through the association with diminished maternal responsiveness and engagement with their children.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R21 NR010857-01) awarded to Melissa L. Sturge-Apple, and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH071256) awarded to Patrick T. Davies and Dante Cicchetti.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1 ½ to 5. Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; Burlington, VT: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD. Object relations, dependency, and attachment: A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship. Child Development. 1969;40:969–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 16.0 User's Guide. Smallwaters Corporation; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Barends N. Personality and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 415–438. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:31–63. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. Guilford; NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey M, Papp L. Children's responses to everyday marital conflict tactics in the home. Child Development. 2003;74:1918–1929. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Harold GT, Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM. Child emotional security and interparental conflict. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2002;67:1–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Lindsay L. Does gender moderate the effects of conflict on children? In: Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Child development and interparental conflict. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2001. pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML. The impact of domestic violence on children's development. In: Nicholls TL, Hamel J, editors. Family interventions in domestic violence: A handbook of gender-inclusive theory and treatment. Springer; New York: 2006. pp. 165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptative processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrooks MA, Emde RN. Marital and parent-child relationships: The role of affect in the family system. In: Hinde R, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 1988. pp. 83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CP, Liu W. Parenting toddlers. In: Bornstein ML, editor. Handbook of parenting, Second edition. Vol. I: Children and parenting. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 2002. pp. 45–72. [Google Scholar]

- Engfer A. The interrelatedness of marriage and the mother-child relationship. In: Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1988. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- English D, Marshall D, Stewart A. Effects of family violence on child behavior and health during early childhood. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18(1):43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Marital conflict, parent-child relations, and youth maladjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27(7):951–975. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E, Main M. Frightened, threatening, and dissociative parental behavior in low-risk samples: Description, discussion, and interpretations. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:309–343. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Stein JD, Ritchie KL, Harris SD, Jouriles EN. Parenting behaviors and beliefs of battered women. In: George W, Geffner R, Jouriles EN, editors. Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and applied issues. US: American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1998. pp. 289–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kerig P. Assessing the links between interparental conflict and child adjustment: The conflict and problem-solving scales. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:454–473. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, Kenny ED. Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:339–352. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Buehler C. Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations. 2000;49(1):25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Bogat GA, von Eye A. New directions for research on intimate partner violence and children: Introduction to the special section. European Psychologist. 2007;12:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Graham-Bermann SA. Behavioral observations of parenting in battered women. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:80–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Huth-Bocks AC, Shapiro D,L, Semel MA. The impact of domestic violence on the maternal-child relationship and preschool-age children's functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:275–287. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levendosky AA, Leahy K, Bogat GA, Davidson WS, von Eye A. The impact of domestic violence on women's parenting and infant functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:544–552. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In: Mussen P, editor. Handbook of child psychology. Wiley; New York: 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Boggio R, Jouriles E. Effects of verbal marital conflict on subsequent mother-son interactions in a child clinical sample. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Donnelly W, Boxer P, Lewis T. Marital and severe parent-to-adolescent physical aggression in clinic-referred families: Mother and adolescent reports on co-occurrence and links to child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(1):3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, John RS. Children's exposure to marital aggression: Direct and mediated effects. In: Kantor GK, Jasinski JL, editors. Out of darkness: Contemporary perspectives on family violence. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. pp. 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Figueredo AJ, Koss MK. The effects of systemic family violence on children's mental health. Child Development. 1995;66:1239–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green C. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:137–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Brunner/Mazel; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Owen AE, Thompson MP, Kaslow NJ. The mediating role of parenting stress in the relation between intimate partner violence and child adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:505–513. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Feerick MM. Next steps in research on children exposed to domestic violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6:215–219. doi: 10.1023/a:1024966501143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea JG, Rossman BR. Children exposed to interparental violence: Does parenting contribute to functioning over time? Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2005;5:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Correspondence among informants on parenting: Preschool children, mothers, and observers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:53–68. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families – risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8145 families. Transaction Books; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Boker SM, Cummings EM. Interparental discord and parenting: Testing the moderating role of child and parent gender. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:365–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple M,L, Davies PT, Cummings EM. The impact of interparental hostility and withdrawal on parental emotional unavailability and children's adjustment difficulties. Child Development. 2006;77:1623–1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturge-Apple ML, Davies PT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM. The role of mothers' and fathers' adrenocortical reactivity in spillover between interparental conflict and parenting practices. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;2:215–225. doi: 10.1037/a0014198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]