Abstract

BACKGROUND

Parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells (PESCs) may have future utilities in cell replacement therapies since they are closely related to the female from which the activated oocyte was obtained. Furthermore, the avoidance of parthenogenetic development in mammals provides the most compelling rationale for the evolution of genomic imprinting, and the biological process of parthenogenesis raises complex issues regarding differential gene expression.

METHODS AND RESULTS

We describe here homozygous rhesus monkey PESCs derived from a spontaneously duplicated, haploid oocyte genome. Since the effect of homozygosity on PESCs pluripotency and differentiation potential is unknown, we assessed the similarities and differences in pluripotency markers and developmental potential by in vitro and in vivo differentiation of homozygous and heterozygous PESCs. To understand the differences in gene expression regulation between parthenogenetic and biparental embryonic stem cells (ESCs), we conducted microarray analysis of genome-wide mRNA profiles of primate PESCs and ESCs derived from fertilized embryos using the Affymetrix Rhesus Macaque Genome array. Several known paternally imprinted genes were in the highly down-regulated group in PESCs compared with ESCs. Furthermore, allele-specific expression analysis of other genes whose expression is also down-regulated in PESCs, led to the identification of one novel imprinted gene, inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase F (INPP5F), which was exclusively expressed from a paternal allele.

CONCLUSION

Our findings suggest that PESCs could be used as a model for studying genomic imprinting, and in the discovery of novel imprinted genes.

Keywords: pluripotent stem cells, parthenogenesis, imprinting, homozygosity

Introduction

Pluripotent stem cells closely resembling embryonic stem cells (ESCs) can be isolated from diploid parthenogenetic embryos generated by artificial activation of metaphase II (MII) arrested oocytes in which the genetic material in the second polar body is retained (Mitalipov et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2007a; Dighe et al., 2008). Recently, we reported the generation of several rhesus monkey parthenogenetic embryonic stem cells (PESCs) lines with stable, diploid female karyotypes that were morphologically indistinguishable from biparental, fertilized controls, expressed key pluripotency markers and demonstrated broad differentiation potential (Dighe et al., 2008).

Interestingly, we observed high levels of heterozygosity in all PESC lines at approximately 67% of gene loci that were polymorphic in the oocyte donors as a result of recombination during meiosis. Most PESCs were also heterozygous in the MHC region as they carried haplotypes identical to the egg donor females, indicating that they could provide histocompatible cells suitable for autologous transplantation. In the mouse, homozygous parthenogenetic embryos and PESCs can also be generated by artificial activation of MII oocytes under conditions that do not interfere with second polar body segregation (Hoppe and Illmensee, 1977; Markert and Petters, 1977). The resulting haploid genome is then experimentally diploidized by fusing 2-cell stage blastomeres. Here, we describe similar homozygous rhesus monkey PESCs derived from a spontaneously duplicated, haploid oocyte genome. Since the effect of homozygosity on PESCs pluripotency and differentiation potential is unknown, we assessed the similarities and differences in pluripotency markers and developmental potential by in vitro and in vivo differentiation in two genetically distinct PESC lines.

Although ESCs derived from fertilized embryos have been studied by global gene expression profiling, comparisons between biparental ESCs and PESCs have been limited to the analysis of marker expression and differentiation potential (Kim et al., 2007a; Dighe et al., 2008). Therefore, a major question still remained; are PESCs distinct or equivalent to ESCs in terms of global gene expression patterns? To address this question, we compared genome-wide expression profiles of monkey ESCs and PESCs. Furthermore, because the transcriptome of PESCs might be affected by genetic background, both heterozygous and homozygous cell lines were profiled.

In contrast to their fertilized counterparts, PESCs with both alleles of maternal origin should lack expression of paternally imprinted genes. Thus, we hypothesized that the transcriptional profiling of PESCs could aid in the identification of novel paternally expressed imprinted genes. Indeed, several known paternally expressed imprinted genes in humans (Morison et al., 2005) were among the most down-regulated genes in PESCs when compared with biparental ESCs. We also selected 12 highly down-regulated putative-imprinted genes in PESCs and analyzed their imprinting status by allele-specific expression analysis. We identified one novel paternally imprinted gene, INPP5F, which was exclusively expressed from a paternal allele.

Conversely, PESCs with two sets of maternal chromosomes should display up-regulation of maternally imprinted genes due to biallelic expression. However, expression levels of known maternally expressed imprinted genes in PESCs were similar to control ESCs suggesting that parthenotes may not be suitable for screening of novel maternally imprinted genes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult rhesus females were used for oocyte collections. Throughout the study period the animals were maintained in facilities fully accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and all experimentation was conducted in accordance with the guidelines contained within the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the ONPRC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, and USDA.

Parthenogenetic activation, fertilization by intracytoplasmic sperm injection and embryo culture

Controlled ovarian stimulation and oocyte recovery has been described previously (Dighe et al., 2008). Oocytes, stripped of cumulus cells by mechanical pipetting after brief exposure (1 min) to hyaluronidase (0.5 mg/ml), were placed in chemically defined, protein-free hamster embryo culture medium (HECM)-9 medium at 37°C in 5% CO2, 5% O2 and 90% N2 until further use. Fertilization by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) and embryo culture were performed as described (Mitalipov et al., 2006). Briefly, sperm were diluted with 10% polyvinylpyrrolidone (1:4; Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, http://www.irvinesci.com), and a 5-µl drop was placed in a micromanipulation chamber. A 30-μl drop of TH3 was placed in the same micromanipulation chamber next to the sperm droplet, and both were covered with paraffin oil. The micromanipulation chamber was mounted on an inverted microscope equipped with Hoffman optics and micromanipulators. An individual sperm was immobilized, aspirated into an ICSI pipette (Humagen, Charlottesville, VA, http://www.humagenivf.com) and injected into the cytoplasm of a metaphase II-arrested (MII) oocyte, away from the polar body. After ICSI, injected oocytes were placed in four-well dishes (Nalge Nunc International Co., Naperville, IL, http://www.nalgenunc.com) containing protein-free HECM-9 medium covered with paraffin oil and cultured at 37°C in 6% CO2, 5% O2 and 89% N2.

For parthenogenetic activation, unfertilized MII oocytes were exposed to 5 µM ionomycin (Calbiochem, San Diego, http://www.emdbiosciences.com) for 5 min followed by a 5-h incubation in 2 mM 6-dimethylaminopurine. Oocytes were then placed in four-well dishes (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL, http://www.nalgenunc.com) containing HECM-9 medium and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2, 5% O2 and 90% N2. Embryos at the 8-cell stage were transferred to fresh plates of HECM-9 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Logan, UT, http://www.hyclone.com) and cultured for a maximum of 9 days, with medium change every other day.

ESC and PESC derivation and culture

Zonae pellucidae of expanded blastocysts were removed with brief protease (0.5%) treatment, and inner cell masses (ICMs) were isolated using immunosurgery (Mitalipov et al., 2006). ICMs were plated onto Nunc four-well dishes containing mitotically inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (mEFs) and ESC culture medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F-12 medium (DMEM/F12; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 15% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1% non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen) and 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen). ICMs that attached to the feeder layer and initiated outgrowth were manually dissociated into small cell clumps with a microscalpel and replated onto new mEFs. After the first passage, colonies with ESC-like morphology were selected for further propagation, characterization and low-temperature storage. Medium was changed daily, and ESC colonies were split every 5–7 days by manual disaggregation and replating collected cells onto dishes with fresh feeder layers. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in 3% CO2, 5% O2 and 92% N2. Rhesus ESC lines ORMES-9 and ORMES-22 (Oregon Rhesus Macaque Embryonic Stem) and rPESC-2 (rhesus parthenogenetic embryonic stem cell) lines used in this study were produced in our laboratory and described earlier (Mitalipov et al., 2006; Byrne et al., 2007; Dighe et al., 2008).

Human ESC lines H1 and BG02 used in this study were cultured under the same conditions as rhesus ESCs, except that 20% Knock Out Serum Replacement (KSR; GIBCO) was used instead of FBS in the culture medium supplemented with 4 ng/ml FGF2 (Sigma).

In vitro and in vivo differentiation of ESCs and PESCs

The differentiation methods were performed as previously described (Byrne et al., 2006; Mitalipov et al., 2006; Sparman et al., 2009). For embryoid body (EB) formation, entire colonies were loosely detached from feeder cells and transferred into feeder-free, six-well, ultra-low adhesion plates (Corning Costar, Acton, MA) and cultured in suspension in stem cell medium for 5–7 days. To induce cardiac differentiation, EBs were plated into collagen-coated six-well culture dishes (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA) to allow EB attachment and cultures were maintained in medium for 2–4 weeks. For teratoma production, 3–5 million undifferentiated cells from each cell line were harvested and injected into the hind leg muscle of 4-week old, SCID, beige male mice using an 18 g needle. Six to eight weeks after injection, mice were euthanized and teratoma tumors were dissected, sectioned and histologically characterized for the presence of representative tissues of all three germ layers.

Immunofluorescence procedures

Immunofluorescence protocols have previously been described (Byrne et al., 2006; Mitalipov et al., 2006; Sparman et al., 2009). Undifferentiated and differentiated PESCs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and 0.1% Tween-20. Non-specific reactions were blocked with 10% normal serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Cells were then incubated for 40 min with primary antibodies, washed three times and exposed to secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorochromes (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 40 min. Next, cells were co-stained with 2 µg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min, whole-mounted onto slides and examined under epifluorescence microscopy. Primary antibodies for OCT4, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60 and TRA-1-81 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cytogenetic analysis

Cytogenetic analysis was performed as previously described (Byrne et al., 2006). Briefly, mitotically active PESCs in log phase were incubated with 120 ng/ml ethidium bromide for 40 min at 37°C, 5% CO2, followed by 120 ng/ml colcemid (Invitrogen) treatment for 20–40 min. Cells were then dislodged with 0.25% trypsin, and centrifuged at 200 g for 8 min. The cell pellet was gently resuspended in 0.075 M KCl solution and incubated for 20 min at 37°C followed by fixation with methanol:glacial acetic acid (3:1) solution. Cytogenetic analysis was performed on metaphase cells from each ESC line following standard GTW-banding procedures. Images were acquired using the Cytovision Image Analysis System (Applied Imaging, Santa Clara, CA).

Microsatellite analysis

Microsatellite or short-tandem repeat (STR) genotyping was performed as previously described (Sparman et al., 2009). DNA was extracted from blood or cultured cells using commercial kits (Gentra, Minneapolis, MN). Six multiplexed PCR reactions were set up for the amplification of 44 markers representing 29 autosomal loci, 1 X-linked marker (DXS22 685) and 15 autosomal, MHC-linked loci. Based on the published rhesus monkey linkage map (Rogers et al., 2006), these markers are distributed in about 19 chromosomes. Two of the markers included in the panel, MFGT21 and MFGT22 (Domingo-Roura et al., 1997), were developed from Macaca fuscata and do not have a chromosome assignment. PCRs were set up in 25 µl reactions containing 30–60 ng DNA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM dNTPs, 1X PCR buffer II, 0.5 U Amplitaq (Applied Biosystems) and fluorescence-labeled primers in concentrations ranging from 0.06 to 0.9 µM, as required for each multiplex PCR. Cycling conditions consisted of 4 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C, 30 s at 72°C, followed by 25 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C, 30 s at 72°C and a final extension at 72°C for 30 min. PCR products were separated by capillary electrophoresis on ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fragment size analysis and genotyping was done with the computer software STR and (available at http://www.vgl.ucdavis.edu/informatics/STRand/). Primer sequences for MHC-linked STRs 9P06, 246K06, 162B17(A and B), 151L13, 268P23 and 222I18 were designed from the corresponding rhesus monkey BAC clone sequences deposited in GenBank (accession numbers AC148662, AC148696, AC148683, AC148682, AC148698 and AC148689, respectively). Loci identified by letter ‘D’ prefix were amplified using heterologous human primers.

Methylation analysis of imprinted genes

The methodology for methylation analysis has been previously described (Mitalipov et al., 2007; Sparman et al., 2009). Briefly, gDNA was subjected to bisulfite treatment using a CpG Genome Modification Kit (Chemicon International) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The sequence, annealing temperature and PCR cycle number of each primer pair were as previously reported (Mitalipov et al., 2007). PCR products were cloned and individual clones were then sequenced with an ABI 3100 capillary genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using BigDye terminator sequencing chemistry (Wen, 2001). Sequencing results were analyzed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation).

Qualitative and quantitative expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and further purified using RNeasy spin columns (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA). Final RNA concentrations and purity were determined by spectrophotometry. The integrity of RNA samples was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Total RNA was treated with DNase I before cDNA preparation using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first-strand cDNA was further amplified by PCR using individual primer pairs for specific genes (Table SIII). All PCR samples were analyzed by electrophoresis and visualized on a transilluminator.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis of all imprinted, XIST and telomere length genes has been previously described (Cawthon, 2002; Mitalipov et al., 2007; Sparman et al., 2009). Information regarding sequences and annealing temperatures for each primer can be found in Table SIII. qPCR was performed on total RNA isolated from each PESC line, IVF-derived ORMES-22 and fibroblasts (Mitalipov et al., 2006). The cDNAs were synthesized from 800 ng of total RNA sample with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (200 U/µl) (Invitrogen) using oligo(dT) primers. qPCR was performed on an ABI 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System with the SDS 1.4.0 program and using the ABI TaqMan Fast Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). To test for genomic DNA contamination, all qPCR reactions included a pilot ‘–RT’ control with GAPDH probes and primer set. All reactions were analyzed in duplicates of three biological replicates. For each reaction, we included 5-fold dilutions of pooled cDNA to develop standard curves. The number of amplification cycles required for the fluorescence signal to reach a determined cycle threshold level (CT) was recorded for every sample and an internal standard curve. The RNA equivalent values for genes were calculated using the standard curve method followed by normalization with endogenous housekeeping GAPDH equivalent values derived from the same internal standard curve (Byrne et al., 2006). Relative telomere length was measured using primers Tel1 and Tel2 for telomeres and 36B4 for acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 (RPLP0) used as a single-copy gene reference (Table SIII). To determine the CT value, two separate PCR runs were performed for each sample and primer pair. For each run a standard curve was generated using a reference genomic DNA isolated from IVF-derived ESC diluted to 0.06–40 ng per well (5-fold dilution). Calculation of the relative telomere/single-copy gene ratio (T/S value) and statistical analysis with SDS v. 1.1 software (Applied Biosystems) was used to determine the standard curve and CT values.

Microarray data analysis

Microarray assays were performed at the OHSU Gene Microarray Shared Resource core. RNA samples were converted to labeled cRNA and hybridized to GeneChip Rhesus Macaque Genome Arrays (Affymetrix, Inc.). Gene-Chip operating system version 1.4 software (Affymetrix) was used to process images and generated probe level measurements (.cel files). Microarray data, including CEL and CHP files, can be accessed at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=tjsddkusgemowbk&acc=GSE17964. The information containing microarray analyses can be found in Data S1–S5. Processed image files were normalized across arrays using the robust multichip average algorithm (Irizarry et al., 2003) and log transformed (base 2) to perform direct comparisons of probe set values between samples. GeneSifter (VizX Labs, Seattle, WA) microarray expression analysis software was used to identify differentially expressed transcripts. For a given comparison, one cell line was selected as the baseline reference, and transcripts that exhibited various fold change (ANOVA, P < 0.05; Benjamini and Hochberg correction for false discovery rate) relative to the baseline were considered differentially expressed. To facilitate in-depth comparisons, processed image files were normalized with the robust multichip average algorithm and log transformed (base 2) using the StatView program. Corresponding microarray expression data were analyzed by pairwise differences determined with the student's t-test (P < 0.05).

Allele-specific expression analysis

Characteristics of the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) employed for allele-specific expression analysis, PCR primers and conditions were previously described in detail (Fujimoto et al., 2005; Fujimoto et al., 2006). Expressed alleles were designed using Primer 3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) based on rhesus monkey consensus sequences obtained from GenBank. PCR products were treated with Exonuclease I/Shrimp alkaline phosphatase (ExoSAP-IT kit, USB) prior to sequencing. Sequencing results were analysed using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI). The relative positions of novel polymorphic sites for 12 genes are shown in Table IV. For characteristics of SNPs in human INPP5F, the following primers for PCR amplification were designed based on human consensus sequences obtained from GenBank: hINPP5F-F; 5′-CGGTCCCAGTCTCTTAGCAG-3′, and hINPP5F-R; 5′-CAACCTGGACCATGGAACTT-3′. Expressed alleles were determined with the same primers used in PCR amplification.

Statistical analysis

Microarray analysis was statistically analyzed using ANOVA and the student's t-test. For quantitative analysis of maternally and paternally expressed imprinted genes, Xist expression, and telomere length measurements, statistical analysis with SDS v. 1.1 software (Applied Biosystems) was used.

Results

Genetic and epigenetic profiles of heterozygous and homozygous PESCs

During routine genotyping of rhesus monkey ESC lines derived from in vitro fertilized (IVF) embryos (ORMES series, Mitalipov et al., 2006), we discovered that ORMES-9 displayed complete homozygosity across all analyzed loci. Initially, we employed a panel of 44 microsatellite markers for parentage analysis demonstrating that both the sperm and the egg donors for ORMES-9 carried 35 heterozygous loci (Table SI). Surprisingly, ORMES-9 was homozygous within all examined microsatellite loci that were all inherited from the egg donor with no contribution from the sperm, suggesting that this cell line resulted from a parthenogenetic embryo. To further corroborate this finding, we preformed an SNP analysis with a panel of 60 known SNPs localized to the 3′ ends of rhesus monkey genes (Ferguson et al., 2007). Results confirmed homozygosity of ORMES-9 with only one allele inherited from the female (Table SII). This was an unusual finding since ORMES-9 originated from a blastocyst produced in vitro by ICSI. On other hand, conventional PESCs derived by the retention of the second polar body are highly heterozygous due to meiotic recombination (Dighe et al., 2008). ORMES-9 exhibited a normal diploid female karyotype with no detectable cytogenetic abnormalities.

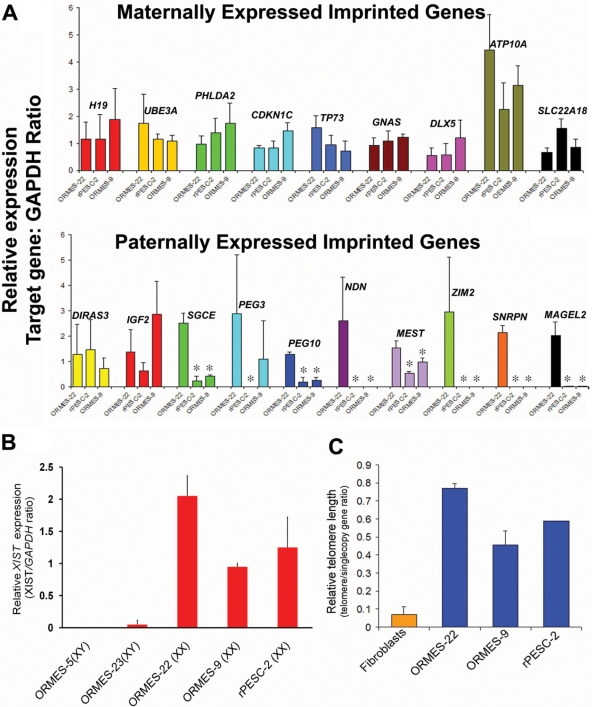

In embryos and ESCs produced by fertilization, imprinted gene expression occurs exclusively or predominantly from one of the parental chromosomes. However, in parthenotes, expression of paternally imprinted genes that are normally silenced by passage through the female germline is not expected, since both alleles are of maternal origin. To further confirm the parthenogenetic nature of ORMES-9, we conducted expression analysis of several known maternally and paternally expressed imprinted genes. Expression levels of nine imprinted genes [H19, Ubiquitin protein ligase E3A (UBE3A), Pleckstrin homology-like domain family A member 2 (PHLDA2), Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C (CDKN1C), Tumor protein p 73 (TP73), GNAS complex locus (GNAS), Homeobox protein DLX-5 (DLX5), Probable phospholipid-transporting ATPase VA (ATP10A) and Solute carrier family 22 member 18 (SLC22A18)] predominantly expressed from the maternal allele were similar to those of previously reported rhesus PESCs, rPESC-2 (Dighe et al., 2008) and IVF-derived ORMES-22 (Fig. 1A). However, transcripts of paternally expressed Necdin (NDN), Zinc-finger gene 2 (ZIM2), Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide N (SNRPN), and MAGE-like 2 (MAGEL2) were absent in both ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 but not in biparental ORMES-22 (Fig. 1A). In addition, expression levels of sarcoglycan, epsilon (SGCE), Paternally expressed 3 (PEG3), Paternally expressed 10 (PEG10), and Mesoderm-specific transcript homolog protein (MEST) were significantly down-regulated in ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 when compared with biparental controls (Fig. 1A). These results are broadly consistent with the conclusion that ORMES-9 originated from a parthenogenetic embryo. Interestingly, high levels of paternally imprinted DIRAS family, GTP-binding RAS-like 3 (DIRAS3) and insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2) were observed in both ORMES-9 and parthenogenetic rPESC-2 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Imprinted gene expression, X-inactivation and telomere length in PESCs. (A) Expression of known maternally (upper panel) and paternally (lower panel) expressed imprinted genes in ORMES-9 as assessed by quantitative (q)PCR. *Expression levels of imprinted genes that were significantly down-regulated in PESCs when compared with biparental controls. (B) X-Inactivation status of primate PESCs determined by expression of XIST. The data represent average fold change relative to GAPDH from three biological replicates. (C) Measurement of relative telomere length in undifferentiated PESCs by qPCR analysis. The data represents the mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Imprinting is generally associated with regulatory regions or imprinting centers (ICs) that consist of differentially methylated domains. We performed methylation analysis of two previously described regions, namely, paternally methylated IGF2/H19 and maternally methylated SNURF/SNRPN ICs in ORMES-9 using a bisulfite sequencing assay (Dighe et al., 2008). In the control biparental ORMES-22, both methylated and unmethylated alleles (clones) were detected within the IGF2/H19 IC comprising 27 individual CpG sites (Supplementary Data, Fig. S1A). In contrast, no methylated clones were observed in ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 (Supplementary Data, Fig. S1A). Conversely, both ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 lines were heavily methylated within the SNURF/SNRPN IC, whereas ORMES-22 contained methylated and unmethylated clones (Supplementary Data, Fig. S1B). These data add another line of evidence supporting the monoparental origin of ORMES-9.

Expression of X (inactive)-specific transcript (XIST), a non-coding nuclear RNA, has been implicated in the process of X chromosome inactivation because of its localization within the inactivation center on the silenced X chromosome (Brown et al., 1991). Thus, its expression is routinely used as an indicator of X-inactivation in female cells. Monkey female somatic cells as well as undifferentiated ESCs display strong XIST expression consistent with X-inactivation (Sparman et al., 2009). However, the status of X-inactivation in PESCs is unknown. To address this matter, we measured levels of XIST expression in parthenogenetic ORMES-9, rPESC-2 and IVF-derived female ORMES-22. Both ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 displayed high levels of XIST comparable to ORMES-22 suggesting that X-inactivation had occurred in parthenogenetic XX ESCs (Fig. 1B). In contrast, XIST transcripts were low to undetectable in XY ESCs (Fig. 1B).

Morphologically, ORMES-9 was indistinguishable from other ESCs derived from fertilized embryos and expressed markers of primate pluripotent stem cells including OCT4, stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA-4), tumor rejection antigen (TRA)-1-60 and TRA-1-81 (Supplementary Data, Fig. S2A). Induced in vitro differentiation resulted in various phenotypes including spontaneously contracting cell aggregates that expressed markers specific for cardiomyocytes and muscle tissue (Supplementary Data, Fig. S2B). When injected into immune-compromised mice, ORMES-9 gave rise to cell lineages representative of all three embryonic germ layers, further demonstrating its broad differentiation potential (Supplementary Data, Fig. S2C).

Telomeres are DNA–protein complexes at the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes that are progressively incised with each cell division in somatic cells leading to replicative senescence (Maser and DePinho, 2002). Maintenance of telomere length and unlimited proliferative potential in ESCs is sustained by ribonucleoprotein complex telomerase (TERT). To provide an additional pluripotency assay, we analyzed the relative telomere length in PESCs in comparison to somatic cells and ESCs derived from fertilized embryos. Both rPESC-2 and ORMES-9 displayed elongated telomere length comparable to IVF-derived ESCs while skin fibroblasts exhibited significantly shortened telomeres (Fig. 1C).

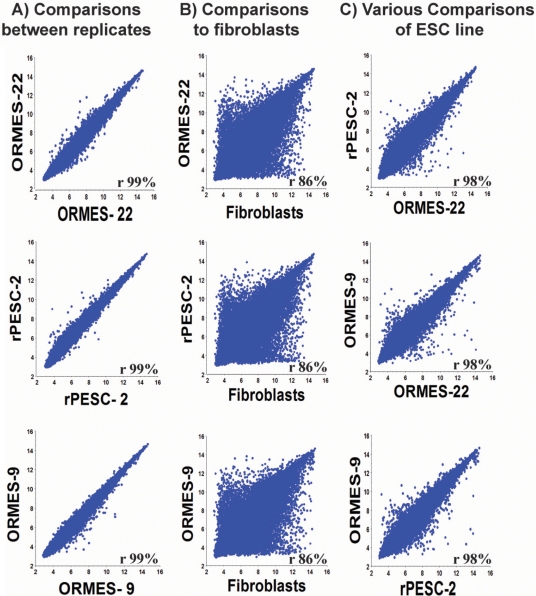

Transcriptional profiling

To define the transcriptional signature of PESCs, we conducted microarray analysis of both ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 lines in comparison to IVF-derived ORMES-22 and adult monkey male skin fibroblasts using the Affymetrix Rhesus Macaque Genome array. Three types of comparisons were performed: (i) three biological replicates of each sample were compared against each other, (ii) each ESC line was compared against skin fibroblasts; and (iii) each PESC line was compared with each other and to IVF-derived ESCs. For each comparison, the detected signal for each probe set was plotted in a scatter graph and the correlation value was calculated. When the biological replicates of each cell type were compared, 99% transcriptional correlation was observed (Fig. 2A and Data S1), suggesting that minimal technical variations were introduced during collection/preparation of RNA samples and subsequent hybridization. Comparison of PESCs to the fibroblasts resulted in a significantly lower transcriptional correlation (Fig. 2B), however, high similarity was observed between PESCs and IVF-derived ESCs (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Microarray expression analysis of PESCs. (A) Comparisons between biological replicates of the same cell line; (B) between PESCs or ESCs and fibroblasts; (C) between PESCs (rPESC-2 and ORMES-9) and IVF-derived ESCs (ORMES-22). X and Y axes indicate gene expression values for each compared cell line, r is correlation value with 95% confidence.

In ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 cell lines, 9722 probe sets were significantly up-regulated (>3-fold difference; ANOVA, P < 0.05) and 10 940 probe sets were down-regulated relative to skin fibroblasts. Analysis of up-regulated genes in parthenogenetic and control IVF-derived ESCs relative to fibroblasts revealed that 5167 probe sets overlapped. We selected 50 genes with the highest fold changes from this group. Several known pluripotency genes were on the top of this list including POU class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1), SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 2 (SOX2), Lin-28 homolog B (LIN28B), Nanog homeobox (NANOG), Claudin 6 (CLDN6), Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 3 (NFE2L3), Gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, beta 3 (GABRB3) and Podocalyxin-like (PODXL) (Table I in bold). These genes were highly expressed in both parthenote lines with comparable fold changes.

Table I.

Genes with the greatest average fold change in monkey PESCs compared with skin fibroblasts.

| Number | Affymetrix probe set ID | Gene name | Gene symbol | Gene expression fold change* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORMES-22 | rPESC-2 | ORMES-9 | ||||

| 1 | MmuSTS.2862.1.S1_at | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 | SPP1 | 395 | 267 | 307 |

| 2 | MmuSTS.2285.1.S1_at | POU class 5 homeobox 1 | POU5F1 | 302 | 262 | 265 |

| 3 | MmugDNA.27729.1.S1_at | SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 2 | SOX2 | 283 | 332 | 272 |

| 4 | MmugDNA.15267.1.S1_at | RNA-binding protein with multiple splicing 2 | RBPMS2 | 234 | 208 | 267 |

| 5 | MmugDNA.14543.1.S1_at | Leucine rich repeat neuronal 1 | LRRN1 | 185 | 166 | 178 |

| 6 | MmugDNA.33796.1.S1_s_at | Lin-28 homolog B | LIN28B | 176 | 210 | 179 |

| 7 | MmugDNA.32128.1.S1_at | Nanog homeobox | NANOG | 175 | 153 | 185 |

| 8 | MmugDNA.38382.1.S1_at | Hypothetical protein LOC696162 | LOC696162 | 173 | 292 | 368 |

| 9 | MmugDNA.35853.1.S1_at | Prominin 1 | PROM1 | 173 | 141 | 169 |

| 10 | MmugDNA.34153.1.S1_at | Claudin 6 | CLDN6 | 171 | 172 | 224 |

| 11 | MmuSTS.3557.1.S1_at | DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 beta | DNMT3B | 170 | 200 | 188 |

| 12 | MmuSTS.3741.1.S1_at | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor-type, Z polypeptide 1 | PTPRZ1 | 155 | 220 | 135 |

| 13 | MmunewRS.875.1.S1_at | Neuroligin 4, Y-linked | NLGN4Y | 142 | 176 | 134 |

| 14 | MmuSTS.1929.1.S1_at | v-myc myelocytomatosis viral-related oncogene, neuroblastoma derived | MYCN | 127 | 109 | 102 |

| 15 | MmugDNA.17159.1.S1_s_at | Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 3 | NFE2L3 | 124 | 138 | 198 |

| 16 | MmuSTS.4813.1.S1_at | Gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, beta 3 | GABRB3 | 119 | 115 | 82 |

| 17 | MmugDNA.20743.1.S1_at | Fraser syndrome 1 | FRAS1 | 109 | 142 | 129 |

| 18 | MmugDNA.33563.1.S1_at | Similar to histone cluster 3, H2a | LOC693768 | 109 | 121 | 109 |

| 19 | MmuSTS.214.1.S1_at | Zic family member 3 | ZIC3 | 106 | 138 | 89 |

| 20 | MmugDNA.19659.1.S1_at | Interleukin 17 receptor D | IL17RD | 105 | 83 | 127 |

| 21 | MmugDNA.15717.1.S1_at | Putative neuronal cell adhesion molecule | PUNC | 103 | 73 | 77 |

| 22 | MmuSTS.4486.1.S1_at | Similar to SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 3 | LOC696412 | 97 | 51 | 54 |

| 23 | MmuSTS.2870.1.S1_at | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule | EPCAM | 96 | 155 | 156 |

| 24 | MmuSTS.4090.1.S1_at | Left-right determination factor 2 | LEFTY2 | 96 | 55 | 165 |

| 25 | MmugDNA.42677.1.S1_at | Similar to developmental pluripotency associated 4 | LOC706631 | 95 | 116 | 109 |

| 26 | MmugDNA.17017.1.S1_at | Orthodenticle homeobox 2 | OTX2 | 93 | 158 | 125 |

| 27 | MmugDNA.31410.1.S1_at | Hypothetical protein LOC722607 | LOC722607 | 92 | 109 | 163 |

| 28 | MmugDNA.35790.1.S1_at | Solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 3 | SLC7A3 | 90 | 138 | 144 |

| 29 | MmugDNA.12610.1.S1_at | CD200 molecule | CD200 | 89 | 89 | 96 |

| 30 | MmugDNA.14842.1.S1_at | Cysteine-rich secretory protein LCCL domain containing 1 | CRISPLD1 | 85 | 60 | 62 |

| 31 | MmuSTS.1323.1.S1_at | Similar to desmoplakin isoform II | LOC694860 | 78 | 119 | 140 |

| 32 | MmugDNA.33242.1.S1_at | Podocalyxin-like | PODXL | 78 | 109 | 99 |

| 33 | MmugDNA.30027.1.S1_at | KIAA0746 protein | KIAA0746 | 77 | 79 | 53 |

| 34 | MmugDNA.10115.1.S1_at | Activin A receptor, type IIB | ACVR2B | 76 | 102 | 85 |

| 35 | MmugDNA.41979.1.S1_at | Sortilin-related receptor, L(DLR class) A repeats-containing | SORL1 | 75 | 74 | 90 |

| 36 | MmugDNA.21032.1.S1_at | Actin-binding LIM protein 1 | ABLIM1 | 75 | 70 | 71 |

| 37 | MmugDNA.13233.1.S1_at | Brain expressed X-linked 2 | BEX2 | 71 | 77 | 79 |

| 38 | MmugDNA.14104.1.S1_at | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 1A | PPP1R1A | 67 | 65 | 66 |

| 39 | MmugDNA.42748.1.S1_at | Chromosome 9 open reading frame 58 | C9ORF58 | 64 | 85 | 61 |

| 40 | MmuSTS.3925.1.S1_at | Similar to sal-like 2 | LOC708367 | 59 | 69 | 69 |

| 41 | MmuSTS.1436.1.S1_at | Similar to proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase LCK (p56-LCK) (Lymphocyte cell-specific protein-tyrosine kinase) (LSK) (T cell-specific protein-tyrosine kinase) | LOC717810 | 55 | 64 | 111 |

| 42 | MmugDNA.16646.1.S1_at | Par-6 partitioning defective 6 homolog beta | PARD6B | 52 | 59 | 70 |

| 43 | MmugDNA.29316.1.S1_at | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 7 | CHD7 | 51 | 61 | 58 |

| 44 | MmugDNA.36148.1.S1_at | Cytochrome P450, family 26, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | CYP26A1 | 50 | 62 | 75 |

| 45 | MmugDNA.21560.1.S1_s_at | CD24 molecule | CD24 | 49 | 73 | 56 |

| 46 | MmuSTS.3354.1.S1_at | Hypothetical protein LOC697860 | LOC697860 | 49 | 66 | 55 |

| 47 | MmugDNA.31898.1.S1_s_at | Apolipoprotein E | APOE | 49 | 55 | 75 |

| 48 | MmugDNA.1925.1.S1_at | Similar to frizzled 5 | LOC710796 | 48 | 86 | 83 |

| 49 | MmugDNA.14234.1.S1_at | Cyclin D2 | CCND2 | 48 | 52 | 52 |

| 50 | MmugDNA.18039.1.S1_at | DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 alpha | DNMT3A | 41 | 41 | 43 |

Bold fonts represent known pluripotency genes. *The fold change was calculated for each stem cell line versus the level of expression for a particular gene in adult monkey skin fibroblasts. ORMES-9 and ORMES-22 represent Oregon Rhesus Macaque Embryonic Stem-9 and -22, respectively, and rPESC-2 represent rhesus parthenogenetic embryonic stem cell.

As described above, in monoparental PESCs, a subset of imprinted genes normally expressed from the paternal allele are silenced or significantly down-regulated. Here, we used transcriptome analysis of PESCs to corroborate these observations. We also hypothesized that PESCs can be used to screen for novel paternally imprinted genes. Analysis of the microarray data identified 197 genes that were down-regulated (≤2-fold change, P < 0.05) in both ORMES-9 and rPESC-2 lines when compared with biparental ORMES-22 (Data S2). Of these, 25 with the highest fold change were selected for further analysis (Table II). We randomly picked Sorting nexin 5 (SNX5), Forkhead box F2 (FOXF2), Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 IGFBP5) and Homeobox D4 (HOX4D) from this group and validated their microarray expression levels by qPCR (Supplementary Data, Fig. S3). Interestingly, eight genes in this group were well-known paternally expressed imprinted genes [SNRPN, Pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 (PLAGL1), PEG3, NDN, PEG10, GNAS1 antisense (NESPAS), Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 5 (NAP1L5) and MAGEL2] (Table II, in bold). These results suggest that the transcriptional variation observed between parthenogenetic and biparental ESC samples is biological in origin. Comparisons of parthenogenetic cell lines to the biparental ESCs also identified 316 probe sets/genes that were significantly up-regulated (≥2-fold change, P < 0.05) in both parthenotes (Data S3). A group of 25 genes from this category with the greatest fold change is presented in Table III. PESCs with two sets of maternal chromosomes might be expected to show up-regulation of maternally imprinted genes due to biallelic expression. However, in agreement with our qPCR data, no known maternally expressed imprinted genes were present in this group.

Table II.

Highly down-regulated genes in PESCs compared with ESC controls.

| Number | Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Gene name | Gene symbol | Gene expression fold change* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rPESC-2 (heterozygous parthenote) | ORMES-9 (homozygous parthenote) | ||||

| 1 | MmugDNA.26310.1.S1_at | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide N | SNRPN | 161 | 107 |

| 2 | Mmu.16433.2.S1_at | Collagen, type III, alpha 1 | COL3A1 | 25 | 29 |

| 3 | MmuSTS.1142.1.S1_at | Similar to pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 isoform 2 | PLAGL1 | 17 | 18 |

| 4 | MmugDNA.12446.1.S1_at | Paternally expressed 3 | PEG3 | 14 | 15 |

| 5 | MmuSTS.1946.1.S1_at | Necdin | NDN | 14 | 14 |

| 6 | MmugDNA.38558.1.S1_at | Paternally expressed 10 | PEG10 | 13 | 13 |

| 7 | MmugDNA.36408.1.S1_at | Carbonic anhydrase III, muscle specific | CA3 | 6 | 9 |

| 8 | MmuSTS.1960.1.S1_at | Forkhead box D1 | FOXD1 | 8 | 8 |

| 9 | MmugDNA.23547.1.S1_at | Sorting nexin 5 | SNX5 | 8 | 7 |

| 10 | MmugDNA.21169.1.S1_at | Similar to chondroitin beta1,4 N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2 | LOC703703 | 7 | 8 |

| 11 | MmugDNA.19752.1.S1_at | Forkhead box F2 | FOXF2 | 8 | 6 |

| 12 | MmugDNA.11688.1.S1_at | Chromosome 3 open reading frame 52 | C3ORF52 | 5 | 5 |

| 13 | MmugDNA.1188.1.S1_at | GNAS1 antisense | NESPAS | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | MmugDNA.15601.1.S1_at | Methyltransferase 10 domain containing | METT10D | 4 | 5 |

| 15 | MmugDNA.40734.1.S1_at | Actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1 | ACTC1 | 4 | 5 |

| 16 | MmugDNA.3198.1.S1_at | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade E (nexin, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1), member 1 | SERPINE1 | 4 | 5 |

| 17 | MmugDNA.42888.1.S1_at | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 | IGFBP5 | 4 | 4 |

| 18 | MmugDNA.35544.1.S1_at | Nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 5 | NAP1L5 | 4 | 4 |

| 19 | MmugDNA.35385.1.S1_at | Homeobox D4 | HOXD4 | 4 | 4 |

| 20 | MmugDNA.33494.1.S1_at | Similar to ELAV-like 2 isoform 3 | LOC708195 | 5 | 3 |

| 21 | MmugDNA.10922.1.S1_at | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase F | INPP5F | 4 | 4 |

| 22 | MmugDNA.31587.1.S1_at | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type B | PTPRB | 4 | 4 |

| 23 | MmugDNA.29862.1.S1_at | Centrosomal protein 68 kDa | CEP68 | 4 | 3 |

| 24 | MmuSTS.1453.1.S1_at | MAGE-like 2 | MAGEL2 | 3 | 3 |

| 25 | MmugDNA.17878.1.S1 at | Transmembrane 4 L Six family member 19 | TM4SF19 | 3 | 3 |

Bold fonts are known paternally expressed imprinted genes. *The fold change (decrease) was calculated for PESCs versus the level of expression for a particular gene in the conventionally derived ORMES-22. ORMES-9 and ORMES-22 represent Oregon Rhesus Macaque Embryonic Stem-9 and -22, respectively and rPESC-2 represent rhesus parthenogenetic embryonic stem cell.

Table III.

Highly up-regulated genes in rhesus PESCs compared with ESC controls.

| Number | Affymetrix Probe Set ID | Gene name | Gene symbol | Gene expression fold change* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rPESC-2 (Heterozygous parthenote) | ORMES-9 (Homozygous parthenote) | ||||

| 1 | MmugDNA.36272.1.S1_at | DCMP deaminase | DCTD | 101 | 78 |

| 2 | MmunewRS.938.1.S1_at | 2-deoxyribose-5-phosphate aldolase homolog | DERA | 93 | 88 |

| 3 | Mmu.12751.1.S1_at | Grancalcin, EF-hand calcium binding protein | GCA | 26 | 31 |

| 4 | MmugDNA.31564.1.S1_at | SH3 domain containing, Ysc84-like 1 (S. cerevisiae) | SH3YL1 | 27 | 24 |

| 5 | MmugDNA.10404.1.S1_at | Sperm-associated antigen 16 | SPAG16 | 13 | 12 |

| 6 | MmugDNA.22282.1.S1_at | WD repeat and FYVE domain containing 1 | WDFY1 | 8 | 14 |

| 7 | MmugDNA.3238.1.S1_s_at | MARVEL domain containing 3 | MARVELD3 | 13 | 13 |

| 8 | MmuSTS.857.1.S1_at | Similar to phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit P isoform 1 | DSCRS | 9 | 10 |

| 9 | MmuSTS.1343.1.S1_at | Adipose differentiation-related protein | ADFP | 11 | 8 |

| 10 | MmugDNA.34151.1.S1_at | Dynein, light chain, Tctex-type 3 | DYNLT3 | 9 | 7 |

| 11 | Mmu.11151.1.S1_s_at | Similar to NADP-dependent leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase (15-oxoprostaglandin 13-reductase) | LTB4DH | 7 | 7 |

| 12 | MmugDNA.22506.1.S1_s_at | Kynureninase (L-kynurenine hydrolase) | KYNU | 7 | 7 |

| 13 | MmugDNA.43436.1.S1_at | Metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 19 | ADAMTS19 | 6 | 6 |

| 14 | MmuSTS.3395.1.S1_at | Similar to T16G12.5 | LOC704499 | 6 | 7 |

| 15 | MmugDNA.30285.1.S1_at | Chromosome 1 open reading frame 115 | C1ORF115 | 6 | 6 |

| 16 | MmugDNA.22401.1.S1_at | Goosecoid homeobox | GSC | 6 | 5 |

| 17 | MmugDNA.40626.1.S1_at | Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 | LGR5 | 6 | 4 |

| 18 | MmuSTS.2514.1.S1_at | Similar to hematopoietically expressed homeobox | LOC699012 | 5 | 5 |

| 19 | MmugDNA.40512.1.S1_at | Chromosome 19 open reading frame 12 | C19ORF12 | 4 | 5 |

| 20 | MmugDNA.12480.1.S1_at | Transmembrane protein 14A | TMEM14A | 5 | 4 |

| 21 | MmugDNA.32146.1.S1_at | Chromosome 7 open reading frame 46 | C7ORF46 | 4 | 5 |

| 22 | MmugDNA.12099.1.S1_at | Transducer of ERBB2, 1 | TOB | 4 | 5 |

| 23 | MmugDNA.15661.1.S1_at | Forkhead box A2 | FOXA2 | 4 | 4 |

| 24 | MmunewRS.87.1.S1_x_at | Similar to zinc-finger protein 528 | LOC720206 | 4 | 4 |

| 25 | MmugDNA.42482.1.S1_at | Chromosome 14 open reading frame 135 | C14ORF135 | 4 | 3 |

*The fold change was calculated for PESCs versus the level of expression in the conventionally derived ORMES-22 line. ORMES-9 and ORMES-22 represent Oregon Rhesus Macaque Embryonic Stem-9 and -22, respectively and rPESC-2 represent rhesus parthenogenetic embryonic stem cell.

Finally, we compared expression profiles of rPESC-2 and ORMES-9 in an effort to define differences between heterozygous and homozygous parthenotes. In the ORMES-9 line, 4626 probe sets were significantly up-regulated (>5-fold difference; t-test, P < 0.05; Data S4) and 3762 probe sets were down-regulated (Data S5) relative to rPESC-2. The majority of the ontologically identified genes in this comparison are associated with cellular, metabolic, biological and developmental processes (Data S4, S5).

Allele-specific expression analysis of candidate imprinted genes

As indicated above, several known imprinted genes were among the top 25 down-regulated genes (Table II). We reasoned that the remaining genes in this group could represent novel paternally imprinted genes. To define the imprinted status of candidate genes, we initially screened a panel of IVF-derived biparental ESC lines (ORMES series, (Mitalipov et al., 2006; Sparman et al., 2009) and their respective parents for informative SNPs. We designed PCR primers within 3′UTR ends for 16 genes in this cohort based on the availability of rhesus monkey consensus sequences in GenBank. At least one informative SNP was identified for 12 of the 16 genes in several analyzed ORMES cell lines (Table IV). However, SNPs were not found for Forkhead box F2 (FOXF2) and similar to ELAV-like 2 isoform 3 (LOC708195) in any of the cell lines analyzed. Additionally, rhesus macaque sequences for Chromosome 3 open reading frame 52 (C3ORF52) and Methyltransferase 10 domain containing (METT10D) were unavailable, and primers designed based on human sequences failed to amplify any PCR product. These outcomes precluded further allele-specific analysis of these four genes.

Table IV.

Summary of allele-specific expression analysis of highly down-regulated genes in PESCs.

| Gene | Genebank accession number | SNP and position | ORMES-1 | ORMES-4 | ORMES-5 | ORMES-7 | ORMES-21 | ORMES-22 | ORMES-23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INPP5F | FJ932755 | C/T, 15 | Paternal | Paternal | Paternal | ||||

| HOXD4 | FJ932754 | A/G 264 | – | – | Paternal | – | |||

| FJ932754 | C/G 298 | – | Biallelic | Paternal | Biallelic | ||||

| ACTC1 | FJ997273 | G/C 162 | – | Paternal | – | – | – | – | |

| FJ997273 | A/G 182 | – | – | – | Biallelic | – | – | ||

| FJ997273 | A/G 211 | Biallelic | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| COL3A1 | FJ932748 | A/T 314 | Biallelic | – | |||||

| FJ932748 | A/G 328 | Biallelic | – | ||||||

| FJ932748 | T/G 333 | Biallelic | – | ||||||

| CA3 | FJ932749 | T/C 427 | Biallelic | – | – | ||||

| FOXD1 | FJ932750 | G/T 77 | Maternal | Biallelic | |||||

| SNX5 | FJ932751 | C/T 100 | Biallelic | Biallelic | |||||

| FJ932751 | A/C 245 | Biallelic | Biallelic | ||||||

| FJ932751 | A/G 320 | Biallelic | Biallelic | ||||||

| LOC703703 | FJ932752 | C/T 24 | Biallelic | Biallelic | – | ||||

| FJ932752 | A/G 461 | – | Biallelic | – | |||||

| SERPINE1 | FJ997274 | G/T 42 | Biallelic | – | – | – | |||

| FJ997274 | C/T 172 | Biallelic | – | – | Biallelic | ||||

| IGFBP5 | FJ932753 | G/T 39 | – | Biallelic | – | ||||

| FJ932753 | T/C 59 | – | Biallelic | – | |||||

| FJ932753 | T/G 222 | Biallelic | Biallelic | – | |||||

| PTPRB | FJ932756 | A/G 169 | Biallelic | ||||||

| CEP68 | FJ932757 | C/A 201 | Biallelic |

ORMES-1 through -23—IVF-derived rhesus monkey ESC lines (ORMES series) (Mitalipov et al., 2006; Sparman et al., 2009). ‘-’No informative SNPs were found. The absence of results indicates that screening for presence of SNPs was not conducted. ORMES represent Oregon Rhesus Macaque Embryonic Stem. ‘SNP and position’ indicates the nucleotide polymorphism and position based on Genebank sequences.

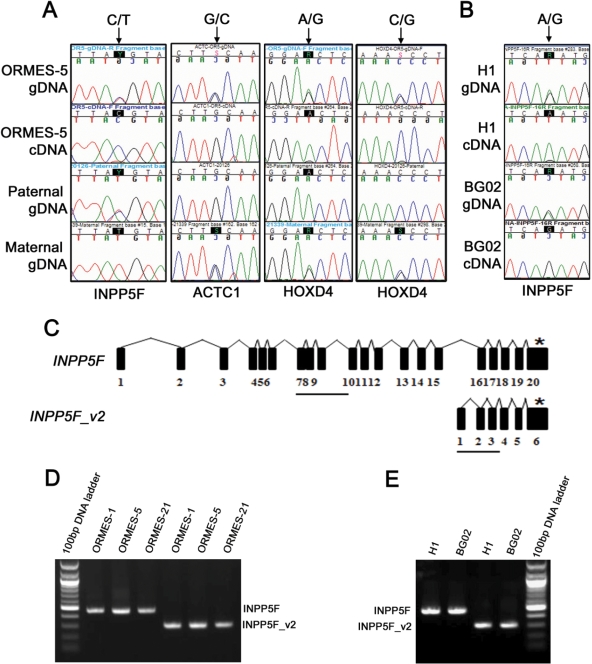

Next, we sequenced cDNA samples in corresponding informative ESC lines. We determined that in all three ESC lines heterozygous for INPP5F (C/T), expression was monoallelic. Moreover, parental analysis of the males and females that contributed their alleles to these ESC lines demonstrated that the expressed allele was exclusively of paternal origin in all three cell lines (Table IV and Fig. 3A). We further analyzed two human ESC lines, H1 and BG02 and determined that both were heterozygous for INPP5F (A/G) and expression of this gene in both human cell lines was also monoallelic (Fig. 3B). Similarly, we determined that Homeobox D4 (HOXD4) and Actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1 (ACTC1) were expressed from the paternal alleles in ORMES-5 (Fig. 3A). However, in two other informative cell lines, expression of these genes was biallelic (Table IV). ACTC1 was also biallelically expressed in informative human BG02 cells based on a G/A polymorphism located in exon 7 (data not shown). Parent-specific expression analysis of nine other genes in this group demonstrated that all were expressed from both alleles. Interestingly, expression of Forkhead box D1 (FOXD1) was biallelic in ORMES-23 but monoallelically expressed from the maternal chromosome in ORMES-22.

Figure 3.

Allele-specific expression analysis of candidate imprinted genes and transcriptional organization of the INPP5F locus. (A) Chromatograms demonstrating paternal expression of INPP5F, ACTC1 and HOXD4 in ORMES-5 cells. Polymorphic nucleotide positions in chromatograms are identified by arrows. For INPP5F, the paternal gDNA was C/T heterozygous while the maternal allele was T/T homozygous. Paternal, C allele was exclusively expressed as detected by cDNA sequencing. Similarly, G/C polymorphism was investigated for ACTC1 showing that expressed G allele in ORMES-5 is of paternal origin. HOXD4 expression was also monoallelic from the paternal allele based on two SNPs (A/G and C/G) in ORMES-5. (B) Chromatograms showing monoallelic expression of INPP5F in two human ESC lines H1 and BG02 based on a G/A polymorphism. (C) Schematic representation (not drawn to scale) of human INPP5F and INPP5F_v2. Horizontal bars indicate amplified regions to differentiate expression of INPP5F and INPP5F_v2. ‘*’The position of a G/A polymorphism. (D) Expression of INPP5F and INPP5F_v2 transcripts in monkey ORMES cell lines and (E) human ESC lines assessed by RT–PCR. The expected size of PCR products for INPP5F and INPP5F_v2 was 466 bp and 299 bp, respectively. ‘Y’, ‘S’ and ‘R’ in the sequences labeling at the top of the chromatograms represent C/T, G/C and A/G polymorphisms, respectively.

Discussion

Therapeutic potential and controversies surrounding ESCs as well as experimentally induced pluripotent stem cells derived by reprogramming of somatic cells using somatic cell nuclear transfer or iPS approaches have been widely discussed. However, a third alternative approach—parthenogenesis—has been considered as suboptimal and sidelined from the stem cell debate. PESCs are unique because their derivation does not involve destruction of viable embryos or genetic transformation using transgenes. Therefore, interest in PESCs has mainly centered on their potential role in cell replacement therapies and their advantages over other alternative pluripotent stem cells including: (i) high efficiency of derivation, similar to their IVF counterparts; (ii) source of histocompatible cells (in terms of both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes) for autologous transplantation to egg donors; and (iii) preclusion of most ethical issues associated with the destruction of potentially viable embryos. However, concerns remain whether or not differentiation and engraftment of PESCs is robust considering the potentially disrupted expression of many paternally imprinted genes. Also, it has yet to be determined whether homozygosity in parthenotes within critical genomic regions compared with IVF-derived cells might affect cell function. Loss of heterozygosity may influence cell survival and differentiation. For example, cells may express multiple genetic defects because all of the recessive mutant alleles on the affected chromosome are unmasked. However, based on our previous observations in the rhesus monkey and published reports in mouse and human PESCs (Kim et al., 2007a; Kim et al., 2007b; Revazova et al., 2007; Dighe et al., 2008), the majority of loci in parthenotes are heterozygous, having undergone meiotic recombination prior to derivation. Such phenomenon may have influenced their high differentiation potential, which is indistinguishable from biparental controls. The discovery of a highly homozygous parthenote cell line presented a unique opportunity to study the effect of zygosity status on differentiation potential and imprinted gene expression in primate PESCs. Since conventional parthenotes created by retention of the second polar body display a significant degree of heterozygosity (Dighe et al., 2008), the homozygosity observed in ORMES-9 suggests that diploidization has occurred after completion of meiosis, possibly during the first mitotic division. An explanation for the mechanism responsible for restoration of a diploid state for this phenomenon is currently unavailable. We recently discovered another homozygous ESC line produced from a fertilized embryo suggesting that spontaneous parthenogenesis following ICSI is not a rare event (unpublished data). Moreover, description of a homozygous parthenote ESC line derived from a human zygote displaying a single pronucleus following conventional IVF supports the notion that ICSI or conventional IVF procedures can induce parthenogenetic oocyte activation without a paternal genetic contribution from the sperm (Lin et al., 2007).

We found that, similar to rPESC-2, expression of most paternally imprinted genes was down-regulated or absent in the homozygous ORMES-9 cell line. Methylation analysis also demonstrated the lack of paternal imprints in these cells. These results are broadly consistent with the conclusion that ORMES-9 is of parthenogenetic origin. We show here that homozygous parthenote ESCs are similar to previously described parthenote cells and biparental ESCs derived from sperm-fertilized embryos with respect to expression of common pluripotency markers, self-renewal and the capacity to generate cell derivatives representative of all three germ layers in vivo and in vitro (Mitalipov et al., 2006; Dighe et al., 2008). Hence, it is reasonable to speculate that loss of heterozygosity does not interfere with PESC pluripotency. However, whether this proves to be the case for all parthenote-derived cells could well depend upon the presence of mutations within homozygous genes in specific cell lines. Further evaluations of in vitro and in vivo differentiation ability of PESCs compared with ESCs must be carried out to fully assess the phenomenon of homozygosity.

Expression profiling revealed that primate PESCs are, in general, transcriptionally similar to ESCs derived from fertilized embryos but divergent from somatic cells. Both strongly express genes implicated in the maintenance of pluripotency, self-renewal, genome surveillance, and cell fate determination in pluripotent stem cells (Sperger et al., 2003; Abeyta et al., 2004; Byrne et al., 2006). However, we show significant differences between the transcriptomes of IVF-derived ESCs and parthenotes. The availability of this global transcriptional signature provides a database that will be an important reference for preclinical testing of PESCs in non-human primates. Perhaps, interpretation of differentially expressed genes in parthenotes will provide insights into the role of such differences in cell differentiation. Recent evidence suggests that, due to the striking similarities between pluripotent stem cells, distinguishing PESCs from those derived from fertilized or cloned embryos will require unequivocal demonstration of genetic homozygosity in selected regions using sensitive genome-wide fingerprinting analyses (Kim et al., 2007b). Several differentially expressed genes between parthenote and biparental cell lines identified in this study may potentially serve as markers of parthenogenetic cells.

As predicted, a list of down-regulated genes in parthenotes includes many known imprinted genes that are normally expressed from the paternal allele. Thus, expression profiling could serve as a sensitive assay to validate known imprinted genes in ESCs and to discover novel paternally imprinted genes. Identification of novel imprinted genes is particularly challenging because monoallelic expression may occur only in one of several possible isoforms, only in particular tissues, or only during particular stages of development. In addition, imprinting of some genes is not absolute, i.e. predominant expression from one of the parental alleles and lower expression levels from the other. Several approaches have been developed to predict or to discover imprinted genes in various tissues including computational methods and expression profiling of tissues carrying uniparental disomies (Schulz et al., 2006; Luedi et al., 2007). Novel imprinted genes have also been identified by assaying monoparental parthenogenetic or androgenetic mouse fetuses (Kobayashi et al., 2000; Mizuno et al., 2002). Here we analyzed the imprinting status of 12 significantly down-regulated candidate genes in primate parthenotes. All but three were expressed biallelically in biparental ESCs suggesting that these genes are not imprinted or have undergone imprint loss. Allele-specific expression analysis demonstrated strictly paternal expression of INPP5F, an inositol phosphatase gene, in rhesus monkey IVF-derived ESCs. Previous studies indicated that mouse and human INPP5F_v2, a splicing variant of INPP5F, is imprinted in the brain and fetal spinal cord tissue but biallelically expressed in other tissues (Choi et al., 2005; Wood et al., 2007). INPP5F_v2 uses an alternative transcriptional start site within intron 15 of parental INPP5F and thus has a unique alternative first exon, but shares four exons and part of the last exon with INPP5F. Using primers specific to INPP5F and INPP5F_v2, we demonstrated that both genes are expressed in monkey and human ESCs. Allele-specific analysis based on the SNP located within the shared untranslated region in the last exon between INPP5F and INPP5F_v2 3′UTR end showed that expressed transcripts were exclusively of paternal origin. Similar analysis of two human ESC lines confirmed that INPP5F is also monoallelically expressed in these cells. Studies using knockout mice suggested that Inpp5f is a functionally important modulator of cardiomyocyte size and cardiac response to stress (Zhu et al., 2009). However, until now the imprinting status of INPP5F remained unknown.

Two other candidate imprinted genes, HOXD4 and ACTC1, were also monoallelically expressed from the paternal allele in one particular cell line, ORMES-5, while expression was biallelic in two other ESC lines. We previously reported dysregulation of imprinted H19 and IGF2 leading to biallelic expression in monkey ESC lines (Fujimoto et al., 2006). Interestingly, ORMES-5 was the only cell line that showed normal maintenance of imprinting and maternal expression of H19. Thus, it is possible that HOXD4 and ACTC1 represent imprinted genes that are susceptible to environmental stress during in vitro culture resulting in loss of imprinting in some ESC lines.

Overall, we define here the transcriptional signature of primate PESCs and similarities and differences in comparison to IVF-produced ESCs, which will provide valuable information for future experiments related to PESCs development and identification. Furthermore, by using allele-specific expression analysis of a panel of down-regulated genes in PESCs, we identified a novel imprinted gene. Additional imprinted genes may be identified using this gene expression database and subsequent procedures.

Authors' roles

S.M. and H.S. designed experiments, collected and assembled data. H.S. performed imprinted gene expression, telomere length, X-inactivation and methylation analysis. H.M. performed allele-specific expression analysis. H.S. performed ESCs culture characterization and differentiation. S.G. analysed teratomas. L.C. performed DNA and RNA isolation. H.S., R.B. and J.H. analysed the microarray data. S.M., H.S., H.M. and D.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

This work was supported by start up funds from Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Stem Cell Center and grants from the Stem Cell Research Foundation and the National Institutes of Health HD057121, HD059946, HD063276, RR000163, HD047675, HD018185 and HD047721.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Division of Animal Resources, Surgical Team, the Assisted Reproductive Technology and Embryonic Stem Cell and Molecular and Cellular Biology Cores at the Oregon National Primate Research Center and Gene Microarray Shared Resource Core at Oregon Health and Science University for providing expertise and services that contributed to this project. We are grateful to Vikas Dighe for technical assistance and Drs. Cecilia Penedo and Betsy Ferguson for microsatellite and SNP analyses.

References

- Abeyta MJ, Clark AT, Rodriguez RT, Bodnar MS, Pera RA, Firpo MT. Unique gene expression signatures of independently-derived human embryonic stem cell lines. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:601–608. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh068. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Lafreniere RG, Powers VE, Sebastio G, Ballabio A, Pettigrew AL, Ledbetter DH, Levy E, Craig IW, Willard HF. Localization of the X inactivation centre on the human X chromosome in Xq13. Nature. 1991;349:82–84. doi: 10.1038/349082a0. doi:10.1038/349082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JA, Mitalipov SM, Clepper L, Wolf DP. Transcriptional profiling of rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:908–915. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.053868. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.106.053868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JA, Pedersen DA, Clepper LL, Nelson M, Sanger WG, Gokhale S, Wolf DP, Mitalipov SM. Producing primate embryonic stem cells by somatic cell nuclear transfer. Nature. 2007;450:497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature06357. doi:10.1038/nature06357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. doi:10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JD, Underkoffler LA, Wood AJ, Collins JN, Williams PT, Golden JA, Schuster EF, Jr, Loomes KM, Oakey RJ. A novel variant of Inpp5f is imprinted in brain, and its expression is correlated with differential methylation of an internal CpG island. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5514–5522. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5514-5522.2005. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.13.5514-5522.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dighe V, Cleeper L, Pedersen D, Byrne J, Ferguson B, Gokhale S, Penedo MC, Wolf D, Mitalipov S. Heterozygous embryonic stem cell lines derived from nonhuman primate parthenotes. Stem Cells. 2008;26:756–766. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0869. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2007-0869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo-roura X, Lopez-giraldez T, Shinohara M, Takenaka O. Hypervariable microsatellite loci in the Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) conserved in related species. Am J Primatol. 1997;43:357–360. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1997)43:4<357::AID-AJP7>3.0.CO;2-W. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2345(1997)43:4<357::AID-AJP7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson B, Street SL, Wright H, Pearson C, Jia Y, Thompson SL, Allibone P, Dubay CJ, Spindle E, Norgren RB., Jr Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) distinguish Indian-origin and Chinese-origin rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) BMC Genomics. 2007;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A, Mitalipov SM, Clepper LL, Wolf DP. Development of a monkey model for the study of primate genomic imprinting. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:413–422. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah180. doi:10.1093/molehr/gah180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A, Mitalipov SM, Kuo HC, Wolf DP. Aberrant genomic imprinting in rhesus monkey embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:595–603. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0301. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2005-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe PC, Illmensee K. Microsurgically produced homozygous-diploid uniparental mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5657–5661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5657. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lerou P, Yabuuchi A, Lengerke C, Ng K, West J, Kirby A, Daly MJ, Daley GQ. Histocompatible embryonic stem cells by parthenogenesis. Science. 2007a;315:482–486. doi: 10.1126/science.1133542. doi:10.1126/science.1133542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Ng K, Rugg-gunn P, Shieh J-H, Oktay kerak O, Jaenisch R, Wakayama T, Moore M, Pedersen R, Daley G. Recombination signatures distinguish embryonic stem cells derived by parthenogenesis and somatic cell nuclear transfer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007b;1:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S, Wagatsuma H, Ono R, Ichikawa H, Yamazaki M, Tashiro H, Aisaka K, Miyoshi N, Kohda T, Ogura A, et al. Mouse Peg9/Dlk1 and human PEG9/DLK1 are paternally expressed imprinted genes closely located to the maternally expressed imprinted genes: mouse Meg3/Gtl2 and human MEG3. Genes Cells. 2000;5:1029–1037. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00390.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Ouyang Q, Zhou X, Gu Y, Yuan D, Li W, Liu G, Liu T, Lu G. A highly homozygous and parthenogenetic human embryonic stem cell line derived from a one-pronuclear oocyte following in vitro fertilization procedure. Cell Res. 2007;17:999–1007. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.97. doi:10.1038/cr.2007.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedi PP, Dietrich FS, Weidman JR, Bosko JM, Jirtle RL, Hartemink AJ. Computational and experimental identification of novel human imprinted genes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1723–1730. doi: 10.1101/gr.6584707. doi:10.1101/gr.6584707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert CL, Petters RM. Homozygous mouse embryos produced by microsurgery. J Exp Zoo. 1977;201:295–302. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402010213. doi:10.1002/jez.1402010213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maser RS, Depinho RA. Connecting chromosomes, crisis, and cancer. Science. 2002;297:565–569. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5581.565. doi:10.1126/science.297.5581.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitalipov SM, Nusser KD, Wolf DP. Parthenogenetic activation of rhesus monkey oocytes and reconstructed embryos. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:253–259. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.1.253. doi:10.1095/biolreprod65.1.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitalipov S, Kuo HC, Byrne J, Clepper L, Meisner L, Johnson J, Zeier R, Wolf D. Isolation and characterization of novel rhesus monkey embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2177–2186. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0125. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2006-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitalipov S, Clepper L, Sritanaudomchai H, Fujimoto A, Wolf D. Methylation status of imprinting centers for H19/IGF2 and SNURF/SNRPN in primate embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:581–588. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0120. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2006-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Sotomaru Y, Katsuzawa Y, Kono T, Meguro M, Oshimura M, Kawai J, Tomaru Y, Kiyosawa H, Nikaido I, et al. Asb4, Ata3, and Dcn are novel imprinted genes identified by high-throughput screening using RIKEN cDNA microarray. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:1499–1505. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6370. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2002.6370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morison IM, Ramsay JP, Spencer HG. A census of mammalian imprinting. Trends Genet. 2005;21:457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.008. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revazova ES, Turovets NA, Kochetkova OD, Kindarova LB, Kuzmichev LN, Janus JD, Pryzhkova MV. Patient-specific stem cell lines derived from human parthenogenetic blastocysts. Cloning Stem Cells. 2007;9:432–449. doi: 10.1089/clo.2007.0033. doi:10.1089/clo.2007.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Garcia R, Shelledy W, Kaplan J, Arya A, Johnson Z, Bergstrom M, Novakowski L, Nair P, Vinson A, et al. An initial genetic linkage map of the rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) genome using human microsatellite loci. Genomics. 2006;87:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.10.004. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Menheniott TR, Woodfine K, Wood AJ, Choi JD, Oakey RJ. Chromosome-wide identification of novel imprinted genes using microarrays and uniparental disomies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl461. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparman M, Dighe V, Sritanaudomchai H, Ma H, Ramsey C, Pedersen D, Clepper L, Nighot P, Wolf D, Hennebold J, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming by somatic cell nuclear transfer in primates. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1255–1264. doi: 10.1002/stem.60. doi:10.1002/stem.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperger JM, Chen X, Draper JS, Aatosiewicz JE, Chon CH, Jones SB, Brooks JD, Andrews PW, Brown PO, Thomson JA. Gene expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and human pluripotent germ cell tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13350–13355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235735100. doi:10.1073/pnas.2235735100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L. Two-step cycle sequencing improves base ambiguities and signal dropouts in DNA sequencing reactions using energy-transfer-based fluorescent dye terminators. Mol Biotechnol. 2001;17:135–142. doi: 10.1385/MB:17:2:135. doi:10.1385/MB:17:2:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AJ, Roberts RG, Monk D, Moore GE, Schulz R, Oakey RJ. A screen for retrotransposed imprinted genes reveals an association between X chromosome homology and maternal germ-line methylation. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030020. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Trivedi CM, Zhou D, Yuan L, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Inpp5f is a polyphosphoinositide phosphatase that regulates cardiac hypertrophic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2009;105:1240–1247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208785. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.