Abstract

Protein acetylation has historically been considered a predominantly eukaryotic phenomenon. Recent evidence, however, supports the hypothesis that acetylation broadly impacts bacterial physiology. To explore more rapidly the impact of protein acetylation in bacteria, microbiologists can benefit from the strong foundation established by investigators of protein acetylation in eukaryotes. To help advance this learning process, we will summarize the current understanding of protein acetylation in eukaryotes, discuss the emerging link between acetylation and metabolism, and highlight the best-studied examples of protein acetylation in bacteria.

Introduction

Since the discovery of post-translational protein acetylation almost fifty years ago (Phillips, 1963, Allfrey et al., 1964), studies of this protein modification have focused primarily on histones and other transcription-associated proteins. Recent reports, however, show that protein acetylation extends far beyond transcription. For example, the mammalian acetylome appears to include more than 2700 acetylated proteins involved in almost every aspect of cellular physiology, including central metabolism, mRNA splicing, protein synthesis and degradation, cell morphology and cell cycle (Choudhary et al., 2009, Zhao et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2006). Thus, as Tony Kouzarides predicted ten years ago, protein modification by acetylation is as common as phosphorylation (Kouzarides, 2000).

During the process of identifying the mammalian acetylome, it became evident that large-scale protein acetylation might also occur in bacterial cells: the mitochondrion, a close relative of α-proteobacteria [reviewed by (Gray et al., 1999)], contains many acetylated proteins (Choudhary et al., 2009, Zhao et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2006). Indeed, recent proteomic studies of two members of the γ-proteobacteria phylum, Escherichia coli (Yu et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2009) and Salmonella enterica (Wang et al., 2010), have respectively identified 144 and 191 acetylated proteins that contribute to diverse cellular processes. These sets of acetylated proteins only partially overlap, which suggests that these initial studies were not saturating and that many more acetylated E. coli and S. enterica proteins likely exist. Investigation of protein acetylation in members of other bacterial phyla is also warranted.

The Biochemistry of Acetylation

Protein N-acetylation, like the more than 300 reported covalent post-translational modifications (Witze et al., 2007), adds complexity to the fundamental twenty amino acid-encoded proteome by increasing the number of distinct protein isoforms (Polevoda & Sherman, 2002, Walsh, 2006). Protein N-acetylation is the transfer of an acetyl group from an acetyl donor, e.g. acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), to the amino terminus of a protein (Nα) or to the ε-amino (Nε) group of a lysine residue (Fig. 1). For both Nα- and Nε-acetylation, an acetyltransferase can establish the proper catalytic microenvironment. The enzyme acts as a scaffold, orienting the acetyl group of acetyl-CoA and the amino group of the acceptor protein into close proximity. The enzyme then promotes deprotonation of the amino group, creating a neutral amino group that serves as a nucleophile that attacks the carbonyl carbon of acetyl-CoA, acetylating the protein and releasing a free CoA molecule (Dyda et al., 2000).

Figure 1. Electron transfer during direct Nε-acetylation from acetyl-CoA.

At neutral pH, the ε-amino group is positively charged. This residue is deprotonated by a base (not shown in figure). (I) The lysine ε-amino group can now act as a nucleophile to attack the electrophilic carbonyl carbon of acetyl-CoA, (II) forming a tetrahedral intermediate. The electron dense oxygen expels the thiolate group (-SCoA). (III) Deprotonation of the amino group (IV) results in an acetylated lysine side chain and CoASH. Figure adapted from (Walsh, 2006).

Nα-acetylation

Nα-acetylation is considered to be an irreversible modification of either the deformylated N-terminal methionine or, following cleavage of the N-terminal methionine, the newly exposed amino acid. In eukaryotes, Nα-acetylation of proteins is extremely common (present on more than 80% of mammalian proteins) and is primarily cotranslational. In bacteria, Nα-acetylation is proposed to be less common, occurring posttranslationally on ribosomal proteins. Six putative Nα-acetyltransferases families have been identified in all domains of life, suggesting a common origin for Nα-acetylation [reviewed by (Polevoda & Sherman, 2003)]. A recent study reported that Nα-acetylation might function as a signal for protein degradation (Hwang et al., 2010).

Nε-acetylation

In contrast to Nα-acetylation, Nε-acetylation is both dynamic and reversible, a property that permits this posttranslational modification to serve in a regulatory capacity. The impact of Nε-acetylation varies according to the context. Nε-acetylation can change the size, charge, and/or conformation of the protein. These changes alter DNA binding affinity, protein stability, protein-protein interactions, protein localization, and protein function. Nε-acetylation also influences other posttranslational modifications [reviewed by (Glozak et al., 2005, Yang & Seto, 2008a)]. Unless otherwise stated, the remainder of this review will focus on the regulation and impact of Nε-acetylation.

Acetylation and deacetylation

Proteins with lysine acetyltransferase activity were historically referred to as HATs because of the extensive early studies on histone acetylation. Due to the observation that non-histone eukaryotic proteins become acetylated and the emergence of protein acetylation in bacteria, which possess no true histones, several authors have proposed to rename lysine acetyltransferases as either KATs (Allis et al., 2007) or LATs (Yang, 2004). Up to five groups of proteins with KAT activity have been identified: 1) the Gcn5-related acetyltransferase (GNAT) family, 2) the MYST family, 3) the CBP/p300 co-activators, 4) the SRC family of coactivators, and 5) the TAFII group of transcription factors [reviewed by (Marmorstein & Roth, 2001, Sterner & Berger, 2000)]. Autoacetylation, an intramolecular covalent modification, has also been reported for several eukaryotic KATs (Tip60 (Wang & Chen, 2010) and p300 (Thompson et al., 2004), for example) and for the E. coli proteins ACS and CheY (Barak et al., 2004).

Of these five groups of KATs, the GNATs are the most widely distributed, with over 10,000 members identified across all three domains of life [reviewed by (Vetting et al., 2005)]. Importantly for bacteriologists, GNATs are ubiquitous within the bacterial domain and are capable of carrying out a diverse range of functions. Some GNATs, such as protein acetyltransferase (Pat) from S. enterica, catalyze Nε-acetylation (Starai & Escalante-Semerena, 2004), while other GNATs perform Nα-acetylation; for example RimI, RimL, and RimJ of E. coli (Tanaka et al., 1989, Yoshikawa et al., 1987). Not all GNATs catalyze protein acetylation. Indeed, the first characterized members of the GNAT family, the aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferases, were discovered as bacterial enzymes that could acetylate and thus inactivate antibiotics [reviewed in (Davies & Wright, 1997, Shaw et al., 1993)].

Two major families of lysine or histone deacetylases (KDACs or HDACs) have been identified. These two families have been grouped into four classes (Gregoretti et al., 2004): the zinc-dependent Rpd3/Hda1 family (classes I, II, and IV) (Yang & Seto, 2008b) and the NAD+-dependent sirtuin family (class III) (Blander & Guarente, 2004). For each KDAC class, putative bacterial homologues have been identified [reviewed by (Hildmann et al., 2007)], but only a few have been shown to serve as protein deacetylases and very few of their protein substrates have been identified (Gardner et al., 2006, Gardner & Escalante-Semerena, 2009, Hildmann et al., 2004, Starai et al., 2002, Wang et al., 2010, Li et al., In press).

Acetylation links metabolism and transcription

In eukaryotic cells, the flow of carbon, and thus cellular energy status, plays a key role in regulating histone acetylation status (Fig. 2). For example, a substantial fraction of the central metabolic enzymes ATP-citrate lyase (ACL, purple lines) and/or acetyl-CoA synthetase (ACS, green lines) can localize to the nucleus, where each can provide acetyl-CoA for histone acetylation: ACL performs this role in mammalian cells that have been exposed to excess glucose, while ACS performs this function in yeast cells exposed to acetate (Wellen et al., 2009, Takahashi et al., 2006). The nuclear localization presumably permits direct delivery of acetyl-CoA to KATs [reviewed by (Ladurner, 2009, Rathmell & Newgard, 2009)]. Similarly, carbon flux dictates the function of sirtuin-dependent histone deacetylation. Since glycolysis consumes NAD+ (blue lines), NAD+-dependent deacetylation by sirtuins is not favoured during rapid metabolism of excess glucose. Instead, sirtuin-dependent deacetylation must await consumption of that glucose and the subsequent recovery of NAD+. For this reason, sirtuins are proposed to communicate the metabolic status of the cell [reviewed by (Buck et al., 2004, Starai et al., 2004, Schwer & Verdin, 2008, Denu, 2005)].

Figure 2. Relevant central metabolic pathways.

Glycolysis (blue) metabolizes glucose to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) in an NAD+-dependent manner. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase. Acetate dissimilation requires the Pta-AckA pathway (red). The enzyme PTA (phosphotransacetylase) converts acetyl-CoA and inorganic phosphate (Pi) into coenzyme A (CoA) and the high-energy pathway intermediate acetyl phosphate (acetyl-P). The enzyme ACKA (acetate kinase) converts acetyl-P and ADP to acetate and ATP. The acetate freely diffuses across the cell envelope into the environment. Acetate assimilation (green) requires the high-affinity enzyme ACS (acetyl-CoA synthetase). In a two-step process that involves an enzyme-bound intermediate (acetyl-AMP), Acs converts acetate, ATP, and CoA into AMP, pyrophosphate (PPi), and acetyl-CoA. The acetyl-CoA replenishes the NAD+-dependent tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (orange). Mammalian ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) uses ATP and CoA to convert the TCA cycle intermediate citrate into oxaloacetate (OAA), ADP, Pi, and acetyl-CoA (purple). Figure adapted from (Wolfe, 2008).

Acetylation controls central metabolic flux

Growing evidence argues that protein acetylation can regulate the flux of carbon through central metabolism. For example, histone acetylation appears to impact expression of central metabolic enzymes. Furthermore, reduced expression of ACL, which results in decreased histone acetylation, is reported to reduce transcription of the genes that encode the glucose transporter Glut4, the glycolytic enzymes hexokinase 2 and phosphofructokinase 1, and the fermentation enzyme lactate dehydrogenase A (Wellen et al., 2009).

The impact of acetylation on central metabolism may not be restricted to transcription. Lysine acetylation of central metabolic enzymes is quite common in both bacteria and eukaryotes (Wang et al., 2010, Zhao et al., 2010, Yu et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2006). Acetylation occurs on proteins involved in many central metabolic processes including the synthesis of acetyl-CoA itself [via ACS and pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)], glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, the TCA cycle and the glyoxylate bypass, glycogen biosynthesis, amino acid biosynthesis, fatty acid metabolism, and urea detoxification (Kim et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2010, Yu & Auwerx, 2009, Zhang et al., 2009).

Since exposure to different carbon sources seems to alter the profile of acetylated central metabolic enzymes, acetylation might regulate metabolic flux, directing carbon down one set of pathways under one condition (e.g. growth on excess glucose) and down a different set under a completely different condition (e.g. growth on a TCA cycle intermediate) (Zhao et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2010). Given that some enzymes that synthesize acetyl-CoA regulate histone acetylation (i.e. ACS and ACL) and/or are themselves acetylated (i.e. ACS and PDH), and given that most central metabolic enzymes can become acetylated, it seems likely that fluctuations in the acetyl-CoA pool(s), and thus acetylation, regulate the expression of central metabolic enzymes and/or the stability of those enzymes and/or their activity, which, in turn, could adjust the acetyl-CoA pools themselves.

Drilling down: two bacterial examples

Now that researchers have begun to compile lists of Nε-acetylated bacterial proteins, the next step is to answer the following questions: Under what condition(s) does a particular protein become Nε-acetylated? How does it become Nε-acetylated? How does Nε-acetylation affect its expression, stability, and/or function? Currently, we possess precious few examples. In fact, virtually everything we know about Nε-acetylation in bacteria comes from the study of two proteins: the central metabolic enzyme ACS and the signalling protein CheY. For ACS, reversible acetylation of a single lysine residue serves as a simple on-off switch that controls the activity of this stand-alone enzyme. For CheY, however, reversible acetylation of multiple lysines coupled with reversible phosphorylation of a single aspartate controls the ability of this signalling protein to form complexes with three distinct protein targets. The physiological consequences of these CheY acetylations remain unclear.

Acetyl-CoA synthetase

In a two-step process, the ubiquitous high-affinity enzyme ACS converts acetate, ATP and CoA into acetyl-CoA, pyrophosphate, and AMP (Fig. 2, green lines). The resultant acetyl-CoA can then be used to generate ATP, produce biosynthetic subunits (Wolfe, 2005, Starai & Escalante-Semerena, 2004), or serve as a source of acetyl groups for modification of proteins (Takahashi et al., 2006, Yang & Seto, 2008a).

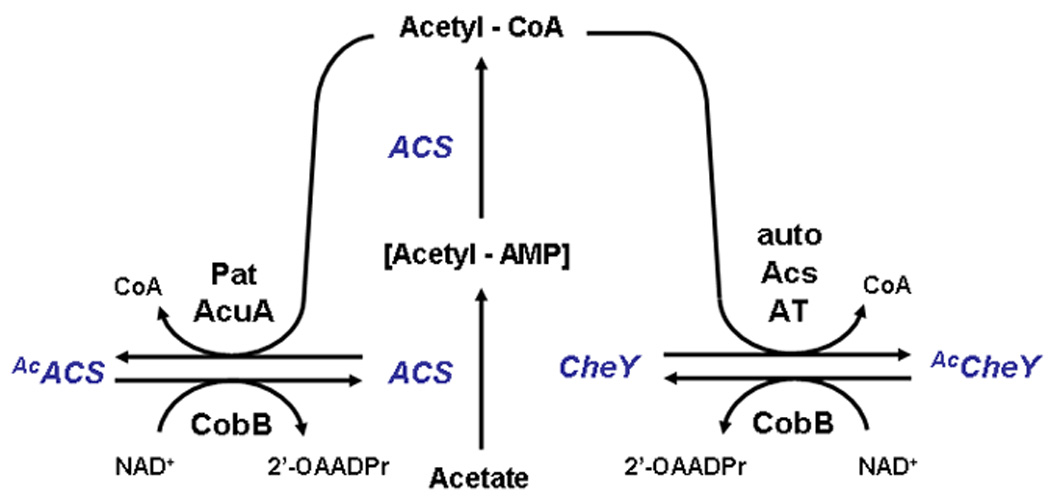

Reversible acetylation regulates ACS activity (Fig. 3). In bacteria, a member of the GNAT family (PAT in S. enterica and AcuA in Bacillus subtilis) inhibits the synthesis of acetyl-AMP by acetylating a lysine residue located within the ACS active site (Gardner et al., 2006, Starai et al., 2002). How acetylation inhibits activity remains unknown; however, reactivation requires removal of the acetyl group (Starai et al., 2002). In S. enterica (Starai et al., 2002, Starai et al., 2003) and mammalian mitochondria (Schwer et al., 2006), this deacetylation reaction is catalyzed by a sirtuin (CobB and SIRT3, respectively). In B. subtilis, reactivation involves both a sirtuin (SrtN) (Gardner & Escalante-Semerena, 2009) and a class I KDAC (AcuC) (Gardner et al., 2006).

Figure 3. Reversible acetylation of ACS and CheY.

The activity of ACS is regulated by reversible acetylation. In a form of feedback inhibition, a GNAT (either Pat or AcuA depending on the organism) uses acetyl-CoA as its acetyl donor to acetylate ACS (AcACS), which is inactive. When the glycolytic carbon source is depleted, NAD+ is recycled (not shown). An NAD+-dependent sirtuin (CobB or SrtN, depending on the organism) can now deacetylate ACS, generating the by-product 2'-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (2'-OAADPr). In B.subtilis, the class III KDAC AcuC also can catalyze deacetylation in an NAD+-independent manner (not shown). Deacetylated, and thus reactivated, ACS can now synthesize acetyl-CoA. The activity of CheY is also regulated by reversible acetylation. In this case, acetylation occurs by autoacetylation (auto), ACS, or some unknown acetyltransferase (AT). CobB deacetylates acetyl-CheY (AcCheY).

The chemotaxis response regulator CheY

As a response regulator of the family of two-component signal transduction systems, CheY autophosphorylates on a conserved aspartyl residue, using its phosphorylated cognate sensor kinase (CheA) as the phosphoryl donor. The resultant phospho-CheY binds with high affinity to the switch component FliM, increasing the probability that the flagellar motor rotates clockwise. Phospho-CheY is unstable, a condition accentuated by the auxiliary phosphatase CheZ [reviewed by (Vladimirov & Sourjik, 2009)].

Intriguingly, CheY has been reported to be N-acetylated in vivo (Yan et al., 2008, Li et al., In press). This acetylation can occur on six lysines located on the carboxy-terminal surface of CheY that interacts with CheA, CheZ, and FliM [reviewed by (Eisenbach, 2007)]. Two CheY acetylation mechanisms have been reported (Fig. 3): autoacetylation using acetyl-CoA as the acetyl donor (Barak et al., 2006) and Acs-catalyzed acetylation using acetate as the acetyl donor (Barak et al., 2004, Barak et al., 1992). A third mechanism, acetylation by a currently unknown acetyltransferase, has been proposed (Yan et al., 2008, Li et al., In press). Two deacetylation mechanisms have been reported: one that depends on Acs, which mediates reversible CheY acetylation (Barak et al., 2004, Barak et al., 1992) and a second that depends on the sirtuin CobB. It is likely, however, that the CobB-dependent mechanism predominates in vivo (Yan et al., 2008, Li et al., In press).

So, what role does CheY acetylation play? Five of the six acetylated lysines participate in the interaction with one or more of the CheY interaction partners. Thus, acetylation could simply inhibit those interactions, essentially protecting some proportion of the total CheY from being acted upon by components of the phosphorylation-dependent signal pathway (Liarzi et al., in press). Surprisingly, a cheA cheZ cobB mutant, which cannot reversibly phosphorylate CheY rapidly nor effectively deacetylate CheY, has been reported to respond robustly to chemotactic repellents. The suggestion is that a phosphorylation-independent repellent response exists and that it involves a protein that can become acetylated - perhaps CheY (Li et al., In press). Other evidence appears to support this conclusion, particularly the observation that replacement of one of the acetylatable lysines with a non-acetylatable arginine results in a defective repellent response (Barak & Eisenbach, 2001). These reports conflict with the well-established dogma that the bacterial chemotaxis absolutely depends on a phosphorylation cascade and that the cell uses the same machinery to respond to both attractants and repellents [reviewed by (Vladimirov & Sourjik, 2009)]. Yet, clearly CheY becomes acetylated and clearly that acetylation can affect function.

What’s next for bacterial protein acetylation?

Whole genome studies are powerful hypothesis generators. Like the early DNA array studies, the pioneering bacterial acetylome studies (Yu et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2010) have provided the microbiology community with a wonderful opportunity to develop and test a large number of hypotheses. For example, does acetylation actually regulate central metabolic flux as proposed (Wang et al., 2010)? If so, how does acetylation alter the function of these central metabolic enzymes? Which acetyltransferases and deacetylases control each reversible acetylation? How are those acetylation-associated enzymes themselves regulated? How do these enzymes recognize their targets?

A few things are certain. First, the list of acetylated bacterial proteins will continue to expand. The initial studies were performed on two closely related bacterial species, each grown under a set of extremely limited conditions. Second, the current list of bacterial protein acetyltransferases and deacetylases will grow. To the best of our knowledge, no bacterial members of the non-GNAT families of acetyltransferases have been reported. Furthermore, the number of known and putative GNATs greatly surpasses the number of known or putative deacetylases. For example, the sirtuin CobB is the only known protein deacetylase in S. enterica or E. coli, yet compelling evidence argues that there must be more (Wang et al., 2010) (L. I. Hu, B. P. Lima and A. J. Wolfe, unpublished data). Third, the impact and regulation of bacterial protein acetylation will be highly nuanced. Many bacterial proteins are acetylated on multiple lysine residues (Barak et al., 2004, Barak et al., 1992, Yu et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2010). Some proteins could be modified by both acetylation and a second modification. For example, CheY is both acetylated and phosphorylated (Eisenbach, 2007). Furthermore, individual subunits of large protein complexes could each be modified. It will be exciting to learn how multiple acetylation events interact and how multiple modifications influence each other. With the recognition that bacterial proteins can be multiply modified, the question arises: could there be a bacterial version of the proposed eukaryotic protein modification code, in which the interactions of multiple posttranslational modifications are read differently by the cell “to define” the function of a given protein (Takahashi et al., 2006, Yang & Seto, 2008a)?

Recent studies in our laboratory have begun to answer some of these questions. For example, we have identified growth conditions that dramatically alter the protein acetylation profile (A. J. Walker and A. J. Wolfe, unpublished data); thus, supporting the hypothesis that bacterial acetylation is indeed regulated (Wang et al., 2010). Furthermore, we possess evidence supporting the nuance and complexity of the system that controls acetylation. For example, we have learned that a putative GNAT and a lysine on the surface of the α subunit of RNA polymerase both inhibit glucose-induced transcription from an extracytoplasmic stress response promoter, while glucose-activated transcription requires a different GNAT, a different lysine on the surface of α, and a phosphorylated response regulator (B. P. Lima and A. J. Wolfe, unpublished data).

As new, highly sensitive technologies for detecting protein modifications develop, we are likely to find that acetylation is not the only bacterial protein acylation. For example, evidence exists that propionyl-CoA and butyryl-CoA both can serve as acyl donors for protein modification. Propionylated and/or butyrylated lysine residues have been identified in histones (Kim et al., 2006, Leemhuis et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2007), CBP/p300 acetyltransferases (Chen et al., 2007, Cheng et al., 2009), and bacterial propionyl-CoA synthetase (PrpE) (Garrity et al., 2007), albeit at lower stoichiometries than acetyllysine residues (Cheng et al., 2009). Like acetylation, both propionylation and butyrylation are likely to be reversible. Members of the CBP/p300 (Cheng et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2007, Leemhuis et al., 2008, Liu et al., 2009), GNAT (Garrity et al., 2007), and MYST (Berndsen et al., 2007) acetyltransferase families can catalyze proprionylation and/or butyrylation, while both modifications can be reversed by sirtuins (Garrity et al., 2007, Smith & Denu, 2007, Cheng et al., 2009, Liu et al., 2009)

In addition to acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, and butyryl-CoA, the list of metabolically relevant acyl-CoA derivatives is quite long. In theory, each could function as an acyl donor (Cheng et al., 2009, Liu et al., 2009). The result of these modifications could be CoA homeostasis via end-product inhibition, as exemplified by acetylation of the acetyl-CoA-producing enzyme ACS and propionylation of the propionyl-CoA-producing enzyme PrpE (Garrity et al., 2007).

Concluding Remarks

Bacteria have long been considered simple relatives of eukaryotes. Obviously, this misperception must be modified. From the presence of a cytoskeleton to the packaging of DNA to the existence of multiple posttranslational modifications, bacteria clearly implement highly sophisticated mechanisms to regulate diverse cellular processes precisely. From even a quick scan of the recently generated lists of acetylated proteins, it is clear that many of these processes are likely regulated by acetylation in bacteria and eukaryotes and, almost certainly, archaea as well. If this is the case, then our deep knowledge of bacterial physiology and the power of bacterial genetics and biochemistry should rapidly advance our understanding of protein acetylation and the diverse cellular processes that it regulates.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Xian-En Zhang and Michael Eisenbach for communication of information prior to publication, Karen Visick and Sylvia Reimann for their helpful comments, and the National Institutes of Health for funding (grant GM066130).

Work cited

- Allfrey VG, Faulkner R, Mirsky AE. Acetylation and Methylation of Histones and Their Possible Role in the Regulation of Rna Synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;51:786–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, Dent S, Jenuwien T, Kouzarides T, Pillus L, Reinberg D, Shi Y, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A, Workman J, Zhang Y. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell. 2007;131:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak R, Eisenbach M. Acetylation of the response regulator, CheY, is involved in bacterial chemotaxis. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:731–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak R, Prasad K, Shainskaya A, Wolfe AJ, Eisenbach M. Acetylation of the chemotaxis response regulator CheY by acetyl-CoA synthetase purified from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:383–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak R, Welch M, Yanovsky A, Oosawa K, Eisenbach M. Acetyladenylate or its derivative acetylates the chemotaxis protein CheY in vitro and increases its activity at the flagellar switch. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10099–10107. doi: 10.1021/bi00156a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak R, Yan J, Shainskaya A, Eisenbach M. The chemotaxis response regulator CheY can catalyze its own acetylation. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:251–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndsen CE, Albaugh BN, Tan S, Denu JM. Catalytic mechanism of a MYST family histone acetyltransferase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:623–629. doi: 10.1021/bi602513x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blander G, Guarente L. The Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:417–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck SW, Gallo CM, Smith JS. Diversity in the Sir2 family of protein deacetylases. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:939–950. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0903424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sprung R, Tang Y, Ball H, Sangras B, Kim SC, Falck JR, Peng J, Gu W, Zhao Y. Lysine propionylation and butyrylation are novel post-translational modifications in histones. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:812–819. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700021-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Tang Y, Chen Y, Kim S, Liu H, Li SS, Gu W, Zhao Y. Molecular characterization of propionyllysines in non-histone proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:45–52. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800224-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Wright GD. Bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:234–240. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denu JM. The Sir 2 family of protein deacetylases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyda F, Klein DC, Hickman AB. GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases: a structural overview. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:81–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbach M. A hitchhiker's guide through advances and conceptual changes in chemotaxis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:574–580. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JG, Escalante-Semerena JC. In Bacillus subtilis, the sirtuin protein deacetylase, encoded by the srtN gene (formerly yhdZ), and functions encoded by the acuABC genes control the activity of acetyl coenzyme A synthetase. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1749–1755. doi: 10.1128/JB.01674-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JG, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM, Escalante-Semerena JC. Control of acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase (AcsA) activity by acetylation/deacetylation without NAD(+) involvement in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:5460–5468. doi: 10.1128/JB.00215-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity J, Gardner JG, Hawse W, Wolberger C, Escalante-Semerena JC. N-lysine propionylation controls the activity of propionyl-CoA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30239–30245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene. 2005;363:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MW, Burger G, Lang BF. Mitochondrial evolution. Science. 1999;283:1476–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoretti IV, Lee YM, Goodson HV. Molecular evolution of the histone deacetylase family: functional implications of phylogenetic analysis. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildmann C, Ninkovic M, Dietrich R, Wegener D, Riester D, Zimmermann T, Birch OM, Bernegger C, Loidl P, Schwienhorst A. A new amidohydrolase from Bordetella or Alcaligenes strain FB188 with similarities to histone deacetylases. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2328–2339. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2328-2339.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildmann C, Riester D, Schwienhorst A. Histone deacetylases--an important class of cellular regulators with a variety of functions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;75:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang CS, Shemorry A, Varshavsky A. N-terminal acetylation of cellular proteins creates specific degradation signals. Science. 2010;327:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1183147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SC, Sprung R, Chen Y, Xu Y, Ball H, Pei J, Cheng T, Kho Y, Xiao H, Xiao L, Grishin NV, White M, Yang XJ, Zhao Y. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Acetylation: a regulatory modification to rival phosphorylation? EMBO J. 2000;19:1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner AG. Chromatin places metabolism center stage. Cell. 2009;138:18–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leemhuis H, Packman LC, Nightingale KP, Hollfelder F. The human histone acetyltransferase P/CAF is a promiscuous histone propionyltransferase. Chembiochem. 2008;9:499–503. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Gu J, Chen Y, Xiao C, Wang L, Zhang Z, Bi L, Wang X, Deng J, Zhang X. CobB regulates Escherichia coli chemotaxis by deacetylating the response regulator CheY. Mol Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07125.x. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liarzi O, Barak R, Bronner V, Dines M, Sagi Y, Shainskaya A, Eisenbach M. Acetylation represses the binding of CheY to its target proteins. Mol Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07148.x. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Lin Y, Darwanto A, Song X, Xu G, Zhang K. Identification and characterization of propionylation at histone H3 lysine 23 in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32288–32295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein R, Roth SY. Histone acetyltransferases: function, structure, and catalysis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DM. The presence of acetyl groups of histones. Biochem J. 1963;87:258–263. doi: 10.1042/bj0870258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoda B, Sherman F. The diversity of acetylated proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-reviews0006. reviews0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevoda B, Sherman F. N-terminal acetyltransferases and sequence requirements for N-terminal acetylation of eukaryotic proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:595–622. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathmell JC, Newgard CB. Biochemistry. A glucose-to-gene link. Science. 2009;324:1021–1022. doi: 10.1126/science.1174665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, Verdin E. Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetyl-CoA synthetase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10224–10229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603968103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwer B, Verdin E. Conserved metabolic regulatory functions of sirtuins. Cell Metab. 2008;7:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw KJ, Rather PN, Hare RS, Miller GH. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:138–163. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.138-163.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BC, Denu JM. Acetyl-lysine analog peptides as mechanistic probes of protein deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37256–37265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Celic I, Cole RN, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science. 2002;298:2390–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Escalante-Semerena JC. Identification of the protein acetyltransferase (Pat) enzyme that acetylates acetyl-CoA synthetase in Salmonella enterica. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:1005–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Takahashi H, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. Short-chain fatty acid activation by acyl-coenzyme A synthetases requires SIR2 protein function in Salmonella enterica and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2003;163:545–555. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starai VJ, Takahashi H, Boeke JD, Escalante-Semerena JC. A link between transcription and intermediary metabolism: a role for Sir2 in the control of acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner DE, Berger SL. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:435–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, McCaffery JM, Irizarry RA, Boeke JD. Nucleocytosolic acetyl-coenzyme a synthetase is required for histone acetylation and global transcription. Mol Cell. 2006;23:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Matsushita Y, Yoshikawa A, Isono K. Cloning and molecular characterization of the gene rimL which encodes an enzyme acetylating ribosomal protein L12 of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:289–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02464895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PR, Wang D, Wang L, Fulco M, Pediconi N, Zhang D, An W, Ge Q, Roeder RG, Wong J, Levrero M, Sartorelli V, Cotter RJ, Cole PA. Regulation of the p300 HAT domain via a novel activation loop. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:308–315. doi: 10.1038/nsmb740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetting MW, LP SdC, Yu M, Hegde SS, Magnet S, Roderick SL, Blanchard JS. Structure and functions of the GNAT superfamily of acetyltransferases. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;433:212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirov N, Sourjik V. Chemotaxis: how bacteria use memory. Biol Chem. 2009;390:1097–1104. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C. Posttranslational modification of proteins : expanding nature's inventory. Publishers, Englewood, Colo: Roberts and Co; 2006. pp. xxi–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen J. SIRT1 regulates autoacetylation and histone acetyltransferase activity of TIP60. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11458–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.087585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhang Y, Yang C, Xiong H, Lin Y, Yao J, Li H, Xie L, Zhao W, Yao Y, Ning ZB, Zeng R, Xiong Y, Guan KL, Zhao S, Zhao GP. Acetylation of metabolic enzymes coordinates carbon source utilization and metabolic flux. Science. 2010;327:1004–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1179687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. ATP-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science. 2009;324:1076–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1164097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witze ES, Old WM, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Mapping protein post-translational modifications with mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:798–806. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe AJ. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:12–50. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe AJ. Quorum sensing "flips" the acetate switch. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5735–5737. doi: 10.1128/JB.00825-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Barak R, Liarzi O, Shainskaya A, Eisenbach M. In vivo acetylation of CheY, a response regulator in chemotaxis of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1260–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ. The diverse superfamily of lysine acetyltransferases and their roles in leukemia and other diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:959–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ, Seto E. Lysine acetylation: codified crosstalk with other posttranslational modifications. Mol Cell. 2008a;31:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ, Seto E. The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: from bacteria and yeast to mice and men. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008b;9:206–218. doi: 10.1038/nrm2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa A, Isono S, Sheback A, Isono K. Cloning and nucleotide sequencing of the genes rimI and rimJ which encode enzymes acetylating ribosomal proteins S18 and S5 of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;209:481–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00331153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu BJ, Kim JA, Moon JH, Ryu SE, Pan JG. The diversity of lysine-acetylated proteins in Escherichia coli. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;18:1529–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Auwerx J. The role of sirtuins in the control of metabolic homeostasis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173 Suppl 1:E10–E19. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04952.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sprung R, Pei J, Tan X, Kim S, Zhu H, Liu CF, Grishin NV, Zhao Y. Lysine acetylation is a highly abundant and evolutionarily conserved modification in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:215–225. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800187-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Xu W, Jiang W, Yu W, Lin Y, Zhang T, Yao J, Zhou L, Zeng Y, Li H, Li Y, Shi J, An W, Hancock SM, He F, Qin L, Chin J, Yang P, Chen X, Lei Q, Xiong Y, Guan KL. Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science. 2010;327:1000–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.1179689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]