Abstract

Anxiety is a commonly occurring psychiatric concern in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). This pilot study examined the preliminary efficacy of a manual-based intervention targeting anxiety and social competence in four adolescents with high-functioning ASD. Anxiety and social functioning were assessed at baseline, midpoint, endpoint, and 6 months following treatment. Treatment consisted of cognitive-behavioral therapy, supplemented with parent education and group social skills training. The treatment program was effective in reducing anxiety in three of the four subjects and improving the social skills in all four subjects. Recommendations for the assessment and treatment of anxiety youth with ASD such as use of self-report measures to complement clinician and parent-reports and adaptations to traditional child-based CBT, are offered.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Autism, Treatment, Anxiety

Introduction

It is widely accepted that the number of people identified with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) has risen over the past decade (US CDC report 2007). This group of neurodevelopmental disorders, which includes Autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), have pervasive deficits in social interaction skills as the defining characteristic. Autistic disorder and PDD-NOS often co-occur with mild to moderate intellectual impairment (Fombonne 2003), but intellectual disability is not required for the diagnosis. By definition children with Asperger’s disorder do not show intellectual deficiency or communication delay. There is evidence that the rise in identified cases of ASD includes a high percentage of children who are not cognitively delayed (so called ‘higher functioning’ cases; Croen et al. 2002; Honda et al. 2005).

In clinical settings, anxiety-related concerns are among the most common presenting problems for school-age children and adolescents with ASD (Ghaziuddin 2002). Severity of anxiety in ASD ranges from mild symptomatic impairment to severe, secondary diagnoses of multiple anxiety disorders (e.g., Bellini 2004; Gadow et al. 2005; Sukhodolsky et al. 2008). A recent review of reports from clinical samples of youth with ASD revealed that between 11 and 84% of children with ASD experience impairing anxiety (White et al. 2009b). Thus, for clinicians and researchers additional attention to the assessment and treatment of anxiety in this population is warranted.

For many youth with ASD, it appears that there is a connection between problems with anxiety and the social impairment that characterizes these disorders. For example, both physiological hyperarousal and social deficits are associated with social anxiety (Bellini 2006). Moreover, cognitive awareness of one’s own social difficulties and previous learning history may contribute to the emergence or promotion of social anxiety. Anxiety, in turn, may exacerbate the social deficit. For example, social avoidance may lead to fewer opportunities in which to practice appropriate social skills (Myles et al. 2001). As both social complexity and social demands rise during middle- and high-school years, adolescents with ASD may become even more aware of their social disabilities (Tantam 2003). This awareness may contribute to the development of secondary mood and anxiety problems (Myles 2003; Myles et al. 2001; Sukhodolsky et al. 2008; Tantam 2003). This may be especially likely for higher functioning individuals with ASD, who may be more cognizant of their social deficits. By simultaneously reducing anxiety and addressing social skill deficits, treatments might be particularly effective with youth with ASD.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the primary, non-pharmacological treatment for childhood mood and anxiety disorders (Ollendick et al. 2006). In the last few years, as the awareness and identification of ASD have increased, so has interest in how CBT might be adapted to treat this clinical population (e.g., Attwood 2004; Greig and MacKay 2005). Only a handful of clinical studies, however, have examined the efficacy of modified CBT for anxiety in ASD (Chalfant et al. 2007; Lehmkuhl et al. 2008; Reaven and Hepburn 2003; Sofronoff et al. 2005; Sze and Wood 2007; Wood et al. 2009). In these studies, traditional CBT was modified to address the needs of youth with ASD. Main modifications include increased structure within sessions, use of visual aids, and considerable parent involvement. Collectively, applications of modified CBT in youth with ASD have shown promise in the treatment of anxiety (White et al. 2009a, b). Other than the treatment protocol of Wood and colleagues (Sze and Wood 2007; Wood et al. 2009), these modified approaches have not addressed the social skill deficits characteristic of this clinical population; the focus has been exclusively on anxiety reduction.

Moreover, there have been no published intervention studies that have addressed anxiety and social competence in adolescents with ASD. Research in this area has focused on younger children, between seven and 13 years of age. Given that certain types of anxiety (i.e., social, self-evaluative anxiety) often emerge during adolescence in people with ASD (Kuusikko et al. 2008), treatment programs specifically targeting adolescents with ASD are warranted. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the preliminary efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral intervention program for anxious adolescents with ASD. Building upon previous research, a treatment program was designed to reduce anxiety and improve social functioning. In this study, adolescents were treated with the alpha version of the treatment program.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited and enrolled via an outpatient specialty clinic for children and adolescents with an ASD. To be eligible, subjects had to be between the ages of 12 and 17 years, have IQ ≥ 70 (based on available report and 2-subtest WASI), have a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, or PDD-NOS and meet criteria for an anxiety disorder (Generalized Anxiety Disorder [GAD], Social Phobia [SoP], Specific Phobia [SP], Agoraphobia [A], or Separation Anxiety Disorder [SAD]) of moderate or greater severity. Adolescents with a diagnosis of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or Panic Disorder were excluded if these disorders warranted another treatment (e.g., trauma narrative, interoceptive exposure, exposure and response prevention).

Four participants were enrolled into the program, two males and two females (see Table 1). Following clinical assessment via a standard clinical interview on developmental history and current functioning by study personnel with further support from the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al. 2002), all subjects were diagnosed with ASD. Presence of anxiety disorders was assessed via the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children—Child/Parent versions (ADIS-C/P; Silverman and Albano 1996). Moderate or greater severity of an anxiety disorder was established by a clinical severity rating (CSR) of four or greater on the ADIS.

Table 1.

Sample description (n = 4)

| Subjecta | Age | Sex | IQb | ASDc | ADIS-C/P:CSRd | SRSe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Todd | 14 | M | 135 | Asperger | SoP:5 | 77 |

| Jodi | 14 | F | 105 | PDD-NOS | SoP:6 GAD:6 OCD:6 SP (wind/thunder):7 SP (airplanes):6 SP (elevators):6 SP (heights):5 PD:4 |

85 |

| Alan | 12 | M | 114 | Asperger | SoP:6 GAD:6 |

75 |

| Margo | 12 | F | 115 | Asperger | SP (BII):7 SP (bees/insects):4 GAD-4 |

87 |

Names assigned to protect confidentiality

IQ based on 2-subtest WASI

ASD diagnosis based on clinical interview and supported by ADI-R and ADOS

ADIS-C/P anxiety disorders reaching clinical significance (i.e., CSR > 4) or subthreshold (CSR = 3) at screen are listed

SRS total SRS T-score at baseline

Intervention Program

Multi-Component Integrated Treatment (MCIT) is a novel treatment program developed specifically for adolescents ages 12 through 17 with high-functioning ASD (see White et al. 2009a, b for more detail). MCIT is a manual-based intervention based on the principles of CBT that integrates promising techniques for social skill development in high-functioning ASD (e.g., modeling, specific feedback, social reinforcement) with evidence-based approaches for the treatment childhood anxiety (e.g., exposure, cognitive challenges, education) modified for ASD. In MCIT, anxiety and deficits in socialization are conceptualized as reciprocal influences. Thus, both anxiety and social skill deficits are targeted in treatment. MCIT is delivered via three modalities—individual therapy, parent education, and group therapy (skills practice). Although manual-based, this short-term, modular cognitive-behavioral treatment program permits flexibility in order to meet individual needs while adhering to the CBT model underlying the program (Chorpita 2007).

The intent of the intervention was primarily to reduce anxiety and secondarily to improve social competence. In most cases, moderate or greater anxiety is addressed in individual therapy before the more didactic teaching and practice of appropriate social skills. The rationale for this sequence is due to the pervasive nature of the social deficits in ASD and the observation that prominent anxiety amplifies social disability. In a time-limited treatment such as MCIT, focus on anxiety is likely to be a more achievable goal that can also have a positive impact on social interaction. The approach to anxiety reduction, however, must be informed by the social disability and cognitive deficits in adolescents with ASD. Moreover, given the longstanding nature of the social deficits in adolescents with ASD, anxiety may be more distressing. Finally, treating anxiety first may promote a sense of mastery over the course of treatment, which may contribute to greater self-efficacy and willingness to work on ‘core’ social deficits.

Individual Therapy

Based on each child’s specific anxiety disorder(s) and the concerns reported by the adolescent and parent, a treatment plan was developed and specific treatment modules were selected for each child. When multiple anxiety disorders were present, treatment focused on the most distressing and impairing anxiety symptom cluster. The manual includes 12–13 individual therapy modules (e.g., initiating social interactions with peers, exposure to anxiety triggers, and relaxation strategies) delivered over 11 weeks. The manual permits flexibility and not all modules are used with all subjects and modules can be repeated as necessary within the confines of 13 total sessions.

The structured individual therapy (as well as all aspects of the intervention) emphasizes the child’s strengths and practice in real-life settings with immediate feedback to facilitate learning. Using various teaching methods (e.g., handouts, hands-on activities), the individual therapy also addresses psychoeducation to promote anxiety management skills (e.g., Chalfant et al. 2007; Sofronoff et al. 2005). In total, MCIT offers up to 13 separate individual therapy modules, typically lasting 50–75 min each. Of these, five modules comprise the ‘core’; they are delivered to all participants and provide the client with an orientation to the treatment, requisite ‘foundation’ skills and psychoeducation for later modules, and a uniform termination/summarization session. The remaining seven to eight modules are delivered based on the client’s unique anxiety-related concerns and social skill deficits and include skills such as relaxation training, handling peer rejection, and strategies for maintaining conversations.

Parent Education/Involvement

Parents were actively involved in the program, acting as ‘coaches’ for exposure exercises during the week, assisting with other homework activities between sessions, and making environmental adaptations as needed (including encouragement and reinforcement for the desired target behaviors). This high level of parent involvement was intended to promote skill generalization and to gather feedback from the parents about their children’s progress during the program. During the last part of each individual therapy session (approximately 15 min), the parent(s) joined the session and the adolescent was asked to summarize the content of the session for their parent and what they learned, as well as the week’s homework assignment. Any current concerns with the program, or the subject’s behavior or progress were reviewed as well. Given the age range of the participants and the importance of developing therapeutic rapport between the adolescent and the therapist, separate therapy sessions with a parent (i.e., without the adolescent present) were not included in the program.

Group Therapy

The group therapy component began after the third or fourth individual therapy session and continued concurrently with the individual therapy. The four adolescents in this study participated in the same 5-session group. The focus of the group treatment sessions was primarily teaching and practicing age-appropriate social skills with peers, rather than anxiety management. However, given that social anxiety (SoP) was common in this group of participants (3 of 4 participants met criteria for SoP), interaction with peers provided opportunities to use anxiety reducing strategies during in vivo exposure experiences. Each group meeting presented a certain skill area such as talking to peers, entering groups, or emotional regulation. The entire treatment program (12–13 individual therapy sessions and 5 group therapy sessions) was intensive and brief, delivered over the course of approximately 11 weeks.

Characterization Measures

Autism diagnostic interview-revised

(ADI-R; Lord et al. 1994). The ADI-R is a structured parent interview used to support a clinical impression of autism. The ADI-R has excellent reliability and validity for diagnosis (Rutter et al. 2008).

Autism diagnostic observation schedule

(ADOS; Lord et al. 1994). A semi-structured, observational assessment conducted with the child, the ADOS maps directly onto diagnostic criteria for ASD. Algorithm scores for communication and socialization are calculated to support the likelihood of ASD diagnosis. Together, the ADI-R and ADOS are commonly used and well-validated instruments to aid the diagnosis of autism.

Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence

(WASI; Wechsler 1999). The 2-subtest WASI (Vocabulary and Matrices) was administered to obtain a general estimate of functioning. The WASI is a nationally standardized brief measure of intelligence that is reliable and valid.

Outcome Measures

Child and adolescent symptom inventory-20

(CASI-20; Sukhodolsky et al. 2008). A brief parent-report scale, the CASI-20 was used to assess anxiety symptoms. The CASI-20 was derived from the larger pool of anxiety items on the Child and Adolescent Symptom Inventory (Gadow and Sprafkin 1994, 1997). Questions that relied heavily on language or reflected other conditions such as ADHD (e.g., motor restlessness) or ASD (e.g., repetitive behaviors) were excluded from the derived scale. Although the measure has not been used previously to assess treatment outcome, there is preliminary evidence for its reliability and utility in ASD samples. In a well-characterized, large sample of youth with ASD, internal consistency was high (alpha = 0.85) and scores were correlated with other indicators of impairment (Sukhodolsky et al. 2008). Each of the 20 items on the CASI-20 is rated on a 0–3 scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, 3 = very often). Items are summed to yield a total anxiety score ranging from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicative of greater anxiety. In the present study, the CASI-20 was chosen as the primary outcome measure because it provides a dimensional measure of anxiety severity without being tied to a specific anxiety disorder.

Anxiety disorders interview schedule for children/parents

(ADIS-C/P; Silverman and Albano 1996). The ADIS-C/P is a clinician-administered diagnostic interview of DSM-IV disorders in children and adolescents. Based on the interview, during which the parent and youth were seen together, the clinician assigned an overall rating of severity (Clinician Severity Rating; CSR) on a 9-point scale, with four or greater indicating a clinical diagnosis (Silverman and Albano 1996). The ADIS (anxiety disorders sections only) was conducted by an independent evaluator (IE), who was not involved in the treatment and was trained to reliability on the ADIS-C/P. Administered at the screening visit, a CSR of 4 or greater was required for inclusion in the study. The ADIS-C/P was also used to assess outcome after treatment and at the follow-up assessment for those disorders reaching clinical significance (CSR ≥ 4) or just below threshold (CSR = 3) at the screening visit. Psychometric properties, such as test-retest reliability (Silverman et al. 2001) and concurrent validity of the ADIS are well established (Wood et al. 2002).

Social responsiveness scale

(SRS; Constantino and Gruber 2005). The SRS is a 65-item, parent-report scale that measures social disability. In addition to the SRS Total score, which is generally used for purposes of diagnostic screening, there are five subscales (social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and autistic mannerisms) that may be used to assess impact of treatment on separate domains of functioning. The SRS was collected at baseline and at endpoint. Internal consistency of the SRS is excellent (α = .97; Constantino and Gruber). Higher scores on the treatment subscales indicate greater severity of social deficit, or more impairment.

Multidimensional anxiety scale for children

(MASC; March 1997). The MASC is a 39-item child self-report measure that assesses the major dimensions of anxiety across four separate subscales: physical symptoms, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation/panic. The MASC also provides an overall index of anxiety symptoms (Total Anxiety Scale), which has been used as an outcome measure in typically developing children with anxiety disorders (Compton and Keeton 2009).The MASC has good reliability (.88) and stability (.93) over 3 months. Higher scores on the MASC reflect greater symptomology. Given that it has not been used extensively with children with ASD, only the Total Anxiety Scale is reported.

Design

A clinical replication series (Barlow et al. 2009) of four cases was employed to evaluate change from baseline to endpoint. Given the pilot nature of this study and the small number of participants, aggregation of data across participants was not pursued. Data were collected at screen (initial visit, in which eligibility for participation was established), baseline (immediately before participants began the intervention program), at the 6-week midpoint in the program, endpoint (1 week following the final treatment session), and follow-up (6 months after treatment ended). The ADIS-C/P was administered during the screening and endpoint visits, and by phone at the 6-month follow-up, an accepted method of ascertainment of diagnoses (Lyneham and Rapee 2005). The 6-month follow-up assessment questionnaires were mailed to the parents.

The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board. Informed consent of the parent and youth assent were obtained prior to data collection. Five adolescents were screened for entry into the study. None of the participants had received prior treatment from the study clinic, and all were assessed for inclusion into the study following consent. One boy was excluded because he did not meet criteria for an ASD. All four participants who enrolled in the trial completed the full treatment program.

Data Analysis

Change in the parent-rated CASI-20 anxiety scale from baseline to endpoint was assessed via the reliable change index (RCI = xEP – xBL/Sdiff; Jacobson and Truax 1991). The RCI can be used to determine if the magnitude of an individual subject’s change following treatment is statistically reliable. Change scores (RCI) greater than 1.96 are considered to be statistically significant and clinically meaningful. Change in social functioning based on the parent-reported SRS scores and change in child-reported anxiety on the MASC were also evaluated via the RCI. Improvement in severity of the child’s primary anxiety disorder (i.e., the disorder targeted in treatment) was evaluated via change on the ADIS-C/P severity rating, from screen to endpoint. Secondary analyses compared the 6-month follow-up scores to those at baseline. All anxiety disorders that were sub-threshold or higher (CSR ≥ 3) at screen were re-administered at follow-up to determine if there was any change in non-targeted anxiety problems. At follow-up, parent-reported scores on the CASI-20 and SRS were compared to baseline to assess maintenance of change over time.

Results

Todd

Todd, a 14-year-old Caucasian male in general education 9th grade, was diagnosed with Asperger’s Disorder. Todd had received play therapy when he was a preschooler following the death of a parent, as well counseling intermittently for several years. In addition to Asperger’s Disorder, he had been previously diagnosed with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder and been treated with Focalin XR and risperidone. The risperidone was discontinued prior to study entry, but he continued on Focalin XR 20 mg per day throughout the trial. On the ADIS-C/P, he met criteria for Social Phobia (SoP; CSR = 5) and no other anxiety disorder. Based on parent and youth-report and clinical observation, Todd was verbally precocious and quite intelligent, but described as shy and rigid (e.g., insistence on routines and things being done a certain way). Socially, he tended to be pedantic and was often perceived as condescending in his social interactions. Reportedly, Todd had no same-age friends and generally stayed to himself at school. At baseline, Todd’s father wanted him to learn how to be more flexible in social interactions, a goal that Todd shared. Todd was inquisitive, with a dry sense of humor and acknowledged some interest in making friends.

Todd’s treatment focused on social skill development. He practiced skills for joining peer groups, cognitive flexibility, and problem-solving. To address the SoP, Todd completed exposure exercises and worked on emotional regulation skills. Initially, Todd denied experiencing social anxiety, instead reporting little interest in peers or saying that they were ‘dumb.’ As treatment progressed, he became more aware of his anxiety and acknowledged that previous experiences of being victimized by peers at school made him reluctant to initiate interactions at school even though he sometimes wanted to do so.

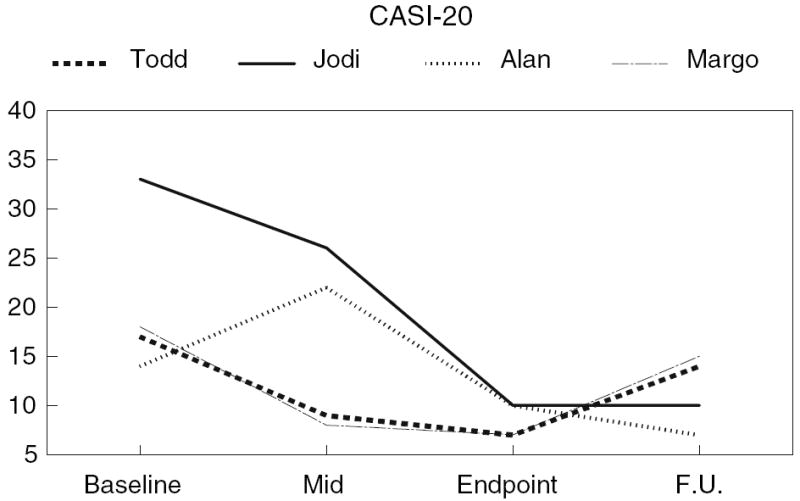

At endpoint, Todd no longer met diagnostic criteria for SoP (CSR = 2) on the ADIS-C/P (Table 2). On the CASI-20, the baseline score of 17 declined to 7 at endpoint (Fig. 1), a statistically significant change (RCI = 2.15). On the MASC, Todd’s Total Anxiety score was low at baseline (36) and endpoint (34). Based on his father’s SRS scores, Todd improved significantly in the area of social communication.

Table 2.

Change in ADIS CSR for primary anxiety disorder targeted in treatment

| Subject | Primary disorder | Baselinea | Endpoint | F.U. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Todd | SoP | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Jodi | SoP | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| Alan | GAD | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Margo | SP(BII) | 7 | 1 | 3 |

ADIS was done at Screen visit, not baseline

F.U. 6-month follow-up

Fig. 1.

Change in CASI-20 scores. Scores [M (SD)]: Baseline [20.50 (8.50)], Midpoint [16.25 (9.10)], Endpoint [8.50 (1.73)], F.U. [10.67 (4.04)]

At the 6-month follow-up, Todd’s SoP remained non-clinical (CSR = 2). His father reported that the Focalin had recently (1 month prior) been discontinued, and Todd was now taking Vyvanse (30 mg, daily). Todd’s CASI-20 score at the follow-up was 14, compared to 17 at baseline and 7 post-treatment. On the SRS, Todd’s Social Communication subscale score remained lower than it was at baseline, but the significant change seen at endpoint was not maintained over time. His Social Motivation subscale at follow-up was consistent with what he obtained at treatment endpoint.

Jodi

Jodi was a 14-year-old biracial female with a diagnosis of PDD-NOS. She attended a regular high school and was in the 9th grade. Jodi had received no previous treatments, other than occupational therapy in school and had never taken psychotropic medication. Other than PDD-NOS, diagnosed at age nine, Jodi had not been given any other mental health diagnoses. However, she had a long history of problems with anxiety and met criteria for several anxiety disorders on the ADIS-C/P at screen: SoP (CSR = 6), GAD (CSR = 6), OCD (CSR = 6), and several SPs (wind/thunderstorms CSR = 7; planes CSR = 6; elevators CSR = 6; heights CSR = 5). Jodi reacted strongly to change in her routine or schedule and exhibited unusual restricted interests (e.g., hoarding potato chip bags and other fragments of paper). Per self-report and parent-report, Jodi often expressed her anxiety as anger and aggression. She would punch walls or walk out of the classroom when upset. Jodi also had many strengths—she was intelligent and motivated to learn about how to decrease her worry. One of her treatment goals was to do homework for 20 min without worry interfering.

Jodi’s treatment first targeted her SoP, as it was reported by Jodi and her father to be the source of greatest impairment at home and with peers. She participated in several in vivo exposure exercises in the community (e.g., using public restrooms, ordering food at a restaurant). The SoP symptoms quickly improved, based on her distress ratings and parent- and self-report, but her symptoms of GAD and the SPs persisted. Thus, exposure sessions moved on to focus on phobias such as wind and thunderstorms and cognitive restructuring exercises to address the GAD symptoms. Wind and thunderstorms were selected over the other SPs (planes, elevators) because she reported feeling more bothered by these fears and they interfered with family life (e.g., needed to call parents if inclement weather was predicted, felt house-bound). Modules addressing social skill development, specifically emotional regulation and flexibility, were incorporated toward the end of treatment.

On the baseline CASI-20, Jodi obtained a score of 33, which declined to 10 at endpoint. This degree of change is statistically significant (RCI = 4.95). Jodi reported no significant change on the MASC Total Anxiety Scale (baseline: 57, endpoint: 42). Jodi’s father reported social improvement in every subscale on the SRS (Table 3). Jodi’s CSR scores showed considerable decline (SoP, CSR = 2; SP wind/thunderstorms, CSR = 0; SP heights, CSR = 0; OCD, CSR = 1; GAD, CSR = 3). The CSRs for other phobias (planes = 7; elevators = 5), areas not addressed during treatment, remained elevated. Jodi reported that although she still experienced worry, she was more able to control it.

Table 3.

Change in SRS T-scores

| SRS scale | Baseline | 6 weeks | Endpoint | FU | Change | RCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Todd | ||||||

| SA | 75 | 62 | 62 | 72 | −13 | 1.29 |

| SC | 65 | 68 | 59 | 70 | −6 | 0.73 |

| CM | 83 | 74 | 66 | 74 | −17 | 2.86* |

| SM | 70 | 59 | 59 | 59 | −11 | 1.36 |

| AM | 67 | 62 | 62 | 71 | −5 | 0.64 |

| Jodi | ||||||

| SA | 66 | 55 | 41 | 45 | −25 | 2.49* |

| SC | 79 | 62 | 45 | 52 | −34 | 4.15* |

| CM | 78 | 66 | 52 | 52 | −26 | 4.38* |

| SM | 77 | 67 | 48 | 48 | −29 | 3.60* |

| AM | 99 | 82 | 58 | 70 | −41 | 5.27* |

| Alan | ||||||

| SA | 52 | 55 | 59 | 62 | 7 | 0.70 |

| SC | 74 | 81 | 68 | 76 | −6 | 0.73 |

| CM | 75 | 69 | 74 | 70 | −1 | 0.17 |

| SM | 70 | 68 | 63 | 68 | −7 | 0.87 |

| AM | 76 | 83 | 80 | 76 | 4 | −0.51 |

| Margo | ||||||

| SA | 77 | 55 | 63 | 59 | −14 | 1.39 |

| SC | 72 | 60 | 69 | 55 | −3 | 0.37 |

| CM | 78 | 72 | 72 | 78 | −6 | 1.01 |

| SM | 75 | 58 | 53 | 62 | −22 | 2.73* |

| AM | 111 | 96 | 79 | 94 | −32 | 4.11 |

SRS subscales: SA social awareness, SC social cognition, CM social communication, SM social motivation, AM autistic mannerisms, Change(E-B) change in T-scores between endpoint (E) and baseline (B), RCI reliable change index based on E-B change

RCI > 1.96 = statistically significant individual change

Based on her father’s report at the 6-month follow-up she continued to show significantly less impairment due to anxiety (CASI-20 = 10) compared to baseline. On the ADIS, however, Jodi met diagnostic criteria for several anxiety disorders (SoP, CSR = 6; SP wind/thunderstorms, CSR = 6; SP planes, CSR = 6; SP elevators, CSR = 4). Her other anxieties did not reach clinical significance: SP, heights (CSR = 3), SP, dark (CSR = 2), SP, loud noises (CSR = 2), GAD (CSR = 2), OCD (CSR = 2). Compared to baseline, her father’s SRS scores continued showed maintenance of treatment gains. However, in some areas (Social Awareness, Social Communication, Autistic Mannerisms), her scores were slightly higher (i.e., more symptomatic) than at treatment endpoint. Jodi received no other treatment or medications between treatment completion and the 6-month follow-up.

Alan

Alan was a 12-year-old Caucasian boy with a diagnosis of Asperger’s Disorder. He was in the 7th grade in a private school. Alan had no previous history of counseling or psychotherapy, but he had been treated with Concerta for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. During the study, he was taking Adderall (50 mg, daily) to help with inattention. He obtained high CSRs in two areas, GAD (6) and SoP (6), on the ADIS-C/P. Based on clinical judgment, GAD was the more impairing and was selected as the initial treatment target. Social anxiety was targeted in the second half of treatment. Alan expressed worries about terrorism, politics, and his future as well as more vague concern about bad things happening to his family. Alan was socially motivated; however, he was small for his age and exhibited unusual behaviors (e.g., odd gestures, high-pitched voice) that made him stand out from his peers. He had a history of being teased and left out of social activities.

At the start of treatment, Alan expressed anxiety about joining into conversations with peers and acknowledged having many negative automatic thoughts (e.g., expecting to be left out, assuming the worst). In treatment, Alan participated in exposure sessions to address GAD, cognitive restructuring to reduce negative automatic thoughts, and practice in emotional regulation skills, as well as several sessions to develop specific social skills (e.g., joining groups, initiating conversations with peers).

On the CASI-20, Alan obtained a baseline score of 14, which dropped to 10 at endpoint (RCI = 0.86, ns). On the MASC, Alan reported a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms on the Total Anxiety Scale (baseline: 73, endpoint: 56; RCI = 2.16). However, based on his mother’s report on the SRS, Alan showed little improvement in social functioning (Table 3). At endpoint, Alan continued to meet criteria on the ADIS-C/P for GAD (CSR = 4), although severity declined from the CSR of 6 prior to treatment. He did not meet criteria for SoP (CSR 3) following treatment.

At follow-up, Alan continued to meet criteria for a diagnosis of GAD (CSR 5) on the ADIS, but experienced little difficulty with SoP (CSR 1). Alan’s CASI-20 score had dropped from 10 (endpoint) to 7. His SRS scores at follow-up indicated no substantial improvement or decline, compared to baseline. Upon completion of the study treatment, Alan began receiving individual treatment with a psychologist for the ADHD and social skills development, per his mother’s report.

Margo

Margo, a 12-year-old Caucasian girl, had a diagnosis of Asperger’s Disorder. She also had previous diagnoses of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Sensory Integration Disorder and Dysgraphia. Margo was in the 6th grade, in a regular education school with some classes in the gifted and talented program. Margo had previously received behavioral counseling (to help with the transition into 6th grade), and occupational and speech therapy at school. She had been tried on several psychotropic medications including Strattera, Adderall, Concerta, Dexedrine, Ritalin, and trazodone. During her treatment in this program, Margo was on Lexapro (30 mg, daily), Focalin XR (20 mg, daily), and Remeron (unknown dosage).

On the ADIS-C/P, she met criteria for SP (BII [Blood-Injection-Injury] type), which was severe (CSR = 7). This phobia resulted in avoidance of going to the doctor. Multiple adults had to apply physical restraint if she needed shots or blood tests. In the initial assessment and treatment sessions, Margo became noticeably upset if the word ‘shot’ was mentioned. She also had a SP of bees and insects (CSR 4). GAD was rated as moderate (CSR 4). Margo had considerable difficulty with peers at school. She was inflexible and frequently insisted that activities (e.g., games in gym class) be done ‘her way.’ Her over-encompassing interest in marine biology often monopolized conversation. She would insist on sharing her knowledge with others regardless of their interest level and she did not recognize other people’s non-verbal cues to move on to other topics. Margo did well academically and lived in a supportive family.

Her treatment focused on the SP (BII) and development of specific social skills (e.g., flexibility, problem-solving). By the end of the third session dedicated to exposure, Margo was watched a video of someone receiving an injection and was able to hold various types of needles and syringes. She practiced most new social skills, such as conversational turn-taking, with family members prior to using them with peers at school. Over time, her mother gradually faded her use of visual cues (e.g., hand gesture to indicate it is time to let the other person have an opportunity to talk).

Margo’s baseline CASI-20 anxiety scale score was 18, dropping to 7 at endpoint, a significant decline (RCI = 2.37). On the MASC, the decrease in her Total Anxiety Scale score was not significant (baseline: 55, endpoint: 50). Margo’s mother reported improvement in the area of social motivation (RCI = 2.73) on the SRS.

At endpoint, Margo’s SP (BII) was no longer clinically significant. Both Margo and her mother assigned fear ratings of 3 on the ADIS-C/P, but reported no avoidance or interference and thus received a clinician-assigned CSR of 1. However, Margo did obtain a CSR of 5 on SP (bees and insects). Her fear of stinging insects such as wasps was not addressed in this time-limited treatment, and the fear did not abate. GAD also no longer met diagnostic criteria (CSR 1).

At the follow-up assessment, Margo was experiencing more symptoms of anxiety than at the end of treatment. The CASI-20 score of 15 was higher than endpoint, but still lower than her baseline score of 18. On the parent-rated ADIS-C/P, Margo obtained a CSR of 3 for her SP of BII. Margo still struggled with symptoms of GAD, although she was rated sub-clinically (CSR 3). Her SP of bees and insects was considerably lower (CSR 1) compared to pretreatment. Margo’s SRS scores were either similar to baseline levels, or improved (i.e., lower). After treatment ended, Margo’s Lexapro and Remeron were discontinued and she was started on Effexor XR (75 mg daily) and Ambien (5 mg daily) for help with sleep.

Discussion

We examined the preliminary efficacy of a time-limited, cognitive-behavioral treatment program for adolescents with ASD and anxiety. The treatment, which included individual and group therapy as well as parental involvement, targeted anxiety reduction and development of social competence concurrently. Few studies have explored the treatment of anxiety and social deficits concurrently in children with ASD. Wood and colleagues (Sze and Wood 2007; Wood et al. 2009) evaluated the efficacy of a CBT intervention for younger children, ages seven to 11. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the combination of individual and group treatment for adolescents with an ASD. As previously discussed, adolescence may be a particularly difficult time for higher functioning youth with ASD due to increasing anxiety and awareness of social difficulties.

On the primary outcome measure, the CASI-20 parent-rated measure of anxiety, three of four participants demonstrated significant improvement from baseline to endpoint. The fourth participant (Alan) showed improvement, but the change was not statistically significant. Although none of the participants had previously been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, all subjects met criteria for at least one anxiety disorder. Three of the four subjects met criteria for multiple anxiety disorders at baseline. The most common disorders in this sample were SoP (n = 3) and GAD (n = 3). For each adolescent, one anxiety disorder was targeted for intervention: SoP for two subjects; GAD and SP (BII) for the other two subjects. Following intervention, three of the participants no longer met diagnostic criteria for their targeted anxiety disorder. The participant with GAD, Alan, continued to meet criteria, although his CSR declined from a 6 to a 4 indicating some improvement.

Improvement in social competence, based on the parent-reported SRS, varied across participants and domain of social functioning. All four participants obtained elevated total T-scores (range: 75–87) on the SRS at baseline. Two participants demonstrated significant improvement in social communication skills and two in the area of social motivation. One participant showed improvement in each of the five treatment subscales of the SRS. The only treatment subscale on which all four subjects exhibited change of at least one standard error of measurement (SEM), a benchmark offered by Constantino and Gruber (2005) as indicative of a significant treatment effect, was Social Motivation. The SRS Social Motivation subscale is a measure of social interest that includes elements of social anxiety.

To our knowledge, this is the first application of the CASI-20 as an outcome measure for anxiety in youth with ASD. The CASI-20 has demonstrated reliability and validity in a sample 170 children with ASD enrolled in psychopharmacology trials (Sukhodolsky et al. 2008). The baseline CASI-20 scores for these four subjects were higher than the mean in the larger sample (M = 13.5 ± 8.5; Sukhodolsky et al. 2008). Given that the subjects in the current study were selected for high levels of anxiety, this observation is not surprising. The potential value of the CASI-20 is that it may serve as a dimensional measure of severity and change in children and adolescents with ASD. Indeed, on the ADIS-C/P, three participants no longer met diagnostic criteria following treatment. The participant who did not show such changes for GAD also failed to show significant decline in anxiety impairment on the CASI-20.

Based on the non-clinical MASC T-scores prior to treatment among a sample of youth all of whom met criteria for at least one anxiety disorder prior to treatment, and the lack of observed change on this measure, the utility of the MASC in this population requires further investigation. Improvement based on MASC scores was not uniform across participants. It is possible that the adolescent participants under-reported anxiety symptoms at baseline leaving little room to detect improvement. Perhaps they did not fully understand some questions on this self-report measure or lacked insight about their own experience with anxiety.

The lack of consistency across participants in maintenance of treatment gains 6 months following treatment completion is a concern. Although two participants were free of their primary anxiety diagnosis at the 6-month follow-up, the other two participants met diagnostic criteria for their targeted anxiety disorders, SoP and GAD. The 6-month follow-up scores on the CASI-20 were also variable. Although all four participants’ scores were lower than at baseline, only one was statistically different from baseline. On the SRS, the only treatment subscale on which all four participants obtained lower scores at follow-up compared to baseline was Social Motivation.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. Although the intent was to conduct a preliminary investigation of a new treatment program, a larger sample will be needed to evaluate the efficacy of the program. The clinician ratings on the ADIS-C/P in this pilot study were done by an independent evaluator who was not involved in the treatment, but not blind to the treatment process. Ideally such assessments would be done by an individual who is masked to treatment condition in a randomized trial. Similarly, parental reports of improvement may have been biased due to attention to the problem and time investment in the program. A randomized trial that controls for attention and time investment might reduce this potential bias. The variability seen in improvement on overall social competence suggests that the intervention may need to enhance the group treatment to realize meaningful change in socialization.

Based on this pilot study and the variability seen in treatment response, the treatment program used in this study was modified and a larger efficacy trial of the expanded program is currently underway. The group therapy component includes more frequent group sessions of longer duration (i.e., seven separate 75-min groups) in order to teach additional social skills and allow greater emphasis on practice within the group. Individual sessions now focus more on exposure and there is greater attention to adapt the presentation of certain skills and concepts to adolescents with ASD (e.g., integration of video- modeled vignettes to demonstrate specific social skills). Despite the aforementioned limitations, these initial results from an uncontrolled, clinical replication series are promising and suggest that further study of this brief cognitive-behavioral treatment program for adolescents with ASD is warranted. In this small sample, the treatment appears acceptable to adolescents and families. Clearly, more rigorous study is needed to learn more about feasibility and efficacy of MCIT.

Discrepancy between parent- and self-report measures is frequently seen in child psychopathology studies (e.g., De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005) as well as in studies of young people with ASD (White et al. 2009a, b). Until a ‘best practice’ approach is established for the assessment of anxiety in youth with ASD, the combined use of parent ratings, clinician ratings and self-reports appears appropriate. In conclusion, the combination of group-based social skills training with individual CBT may be effective in improving social functioning and reducing impairment related to anxiety in adolescents with ASD. Further research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy of this combined approach.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health [1K01MH079945-01; PI: S. W. White]. The authors acknowledge consultation from the grant’s advisory panel: Matthew Fritz, PhD, Cynthia Johnson, PhD, Connie Kasari, PhD, Ami Klin, PhD, Angela Scarpa, PhD, Michael Southam-Gerow, PhD, as well as Roxann Roberson-Nay, PhD. We also thank the participants in this study and their parents, and acknowledge that part of this work was carried out at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Contributor Information

Susan W. White, Department of Psychology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 109 Williams Hall (0436), Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA, sww@vt.edu

Thomas Ollendick, Department of Psychology, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 109 Williams Hall (0436), Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA.

Lawrence Scahill, School of Nursing and Child Study Center, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

Donald Oswald, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA.

Anne Marie Albano, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

References

- Attwood T. Cognitive behaviour therapy for children and adults with Asperger’s syndrome. Behaviour Change. 2004;21:147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Nock MK, Hersen M, editors. Single case experimental designs: Strategies for studying change. 3. Boston MA: Pearson Education Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S. Social skill deficits and anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2004;19:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini S. The development of social anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2006;21:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant A, Rapee R, Carroll L. Treating anxiety disorders in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders: A controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1842–1857. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF. In: Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders Guides to individualized evidence-based treatment. Persons JB, editor. New York: Guilford; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Compton S, Keeton C. Treatment of childhood anxiety disorders: Findings and clinical implications from the Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Treatment Study (CAMS). 2009, March; Symposium presented at the 29th Annual Conference of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America; Tamaya, New Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social responsiveness scale (SRS) Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Croen LA, Grether JK, Hoogstrate J, Selvin S. The changing prevalence of autism in California. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32:207–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1015453830880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: An update. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:365–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Devincent CJ, Pomeroy J, Azizian A. Comparison of DSM-IV symptoms in elementary school-age children with PDD versus clinic and community samples. Autism. 2005;9:392–415. doi: 10.1177/1362361305056079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Child symptom inventory-4. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Adolescent symptom inventory-4 screening manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaziuddin M. Asperger syndrome: Associated psychiatric and medical conditions. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2002;17:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Greig A, MacKay T. Asperger’s syndrome and cognitive behaviour therapy: New applications for educational psychologists. Educational & Child Psychology. 2005;22:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Honda H, Shimizu Y, Imai M, Nitto Y. Cumulative incidence of childhood autism: A total population study of better accuracy and precision. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2005;47:10–18. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusikko S, Pollock-Wurman R, Jussila K, Carter AS, Mattila M, Ebieling H, et al. Social anxiety in high-functioning children and adolescents with autism and asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:1697–1709. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmkuhl HD, Storch EA, Bodfish JW, Geffken GR. Brief report: Exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder in a 12-year-old with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:977–981. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0457-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S. Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, LeCouteur A. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyneham HJ, Rapee RM. Agreement between telephone and in-person delivery of a structured interview for anxiety disorders in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;44:274–282. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS. Multidimensional anxiety scale for children manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Myles B. Behavioral forms of stress management for individuals with Asperger syndrome. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;12:123–141. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles B, Barnhill G, Hagiwara T, Griswold D, Simpson R. A synthesis of studies on the intellectual, academic, social/emotional and sensory characteristics of children with Asperger syndrome. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities. 2001;36:304–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, King NJ, Chorpita BF. Empirically supported treatments for children and adolescents. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescents therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 492–520. [Google Scholar]

- Reaven J, Hepburn S. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in a child with Asperger syndrome: A case report. Autism. 2003;7:145–164. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur AL, Lord C. Autism diagnostic interview revised: WPS edition manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. The anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV—Child and parent versions. San Antonio, TX: Graywind; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pena AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2001;40:937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofronoff K, Attwood T, Hinton S. A randomized controlled trial of a CBT intervention for anxiety in children with Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1152–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Gadow KD, Arnold LE, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, et al. Parent-rated anxiety symptoms in children with pervasive developmental disorders: Frequency and association with core autism symptoms and cognitive functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze KM, Wood JJ. Cognitive behavioral treatment of comorbid anxiety disorders and social difficulties in children with high-functioning autism: A case report. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy. 2007;37:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Tantam D. The challenge of adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;12:143–163. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders-Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2002. Surveillance Summaries, MMWR 2007. 2007;56(No. SS-1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Albano A, Johnson C, Kasari C, Ollendick T, Klin A, et al. Treating anxiety and social deficits in teens with high functioning autism: Development of a cognitive-behavioral intervention program. 2009a doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0062-3. manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T, Scahill L. Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009b;29(3):216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Drahota A, Sze K, Har K, Chiu A, Langer DA. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV. Child and Parent Versions, Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]