Summary

The genome of Borrelia burgdorferi encodes a set of genes putatively involved in cyclic-di-GMP metabolism. Although BB0419 was shown to be a diguanylate cyclase, the extent to which bb0419 or any of the putative cyclic-di-GMP metabolizing genes impact B. burgdorferi motility and pathogenesis has not yet been reported. Here we identify and characterize a phosphodiesterase (BB0363). BB0363 specifically hydrolyzed cyclic-di-GMP with a Km of 0.054 μM, confirming it is a functional cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. A targeted mutation in bb0363 was constructed using a newly developed promoterless antibiotic cassette that does not affect downstream gene expression. The mutant cells exhibited an altered swimming pattern, indicating a function for cyclic-di-GMP in regulating B. burgdorferi motility. Furthermore, the bb0363 mutant cells were not infectious in mice, demonstrating an important role for cyclic-di-GMP in B. burgdorferi infection. The mutant cells were able to survive within Ixodes scapularis ticks after a blood meal from naïve mice; however, ticks infected with the mutant cells were not able to infect naïve mice. Both motility and infection phenotypes were restored upon genetic complementation. These results reveal an important connection between cyclic-di-GMP, B. burgdorferi motility and Lyme disease pathogenesis. A mechanism by which cyclic-di-GMP influences motility and infection is proposed.

Keywords: Spirochete, Borrelia, Lyme disease, c-di-GMP, motility, virulence

Introduction

Bis-(3’-5’)-cyclic-dimeric guanosine monophosphate (cyclic-di-GMP) is a bacterial second messenger that is known to regulate a variety of cellular processes. Although cAMP signaling is reported for both prokaryote and eukaryotes, mounting evidence indicates cyclic-di-GMP signaling is limited to bacterial species (reviewed in Schirmer and Jenal, 2009;Wolfe and Visick, 2008). Cyclic-di-GMP was found to stimulate the synthesis of adhesins and exopolysaccharide matrix substances in biofilm, inhibit motility, control the virulence of bacterial pathogens, regulate progression through the cell cycle, and control antibiotic production (Wolfe and Visick, 2008;Romling et al., 2005;Jenal and Malone, 2006;Cotter and Stibitz, 2007;Dow et al., 2006;Ryan et al., 2007;Tamayo et al., 2007;Duerig et al., 2009;Fineran et al., 2007). Cyclic-di-GMP is produced from two molecules of GTP by diguanylate cyclase and is degraded by specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs). Diguanylate cyclase activity is conferred with the GGDEF functional domain whereas cyclic-di-GMP-specific PDE activity is carried out by unrelated EAL or HD-GYP domains. EAL domain-containing PDEs hydrolyze cyclic-di-GMP to pGpG, and pGpG is subsequently hydrolyzed to two GMP molecules by a nonspecific PDE (commonly known as PDE-B) (Hickman et al., 2005;Paul et al., 2004;Chang et al., 2001;Christen et al., 2005;Tamayo et al., 2005;Schirmer and Jenal, 2009). In contrast, HD-GYP domain-containing PDEs degrade cyclic-di-GMP to two GMPs (Ryan et al., 2009;Ryan et al., 2006;Ryan et al., 2007). These enzymatic domains (GGDEF, EAL, and HD-GYP) can be found associated with a wide range of well-characterized signaling or sensory proteins (Galperin et al., 2001). Analyses of several bacterial genomes indicate they contain multiple (17 – 40) diguanylate cyclases and multiple (24 - 40) PDEs (Galperin et al., 2001). The ability to survive in a variety of environmental niches is postulated to depend upon regulating the concentration of cyclic-di-GMP (Tamayo et al., 2007). Increasing the intracellular level of cyclic-di-GMP by (over)expressing a diguanylate cyclase or inhibiting a PDE promotes biofilm formation, while inhibiting motility and virulence. Many studies show that cyclic-di-GMP exerts effects on cells by binding receptor molecules that then alter the output of target molecules or structures (reviewed in Schirmer and Jenal, 2009;Hengge, 2009). Several types of cyclic-di-GMP receptors have been described, including PilZ, PelD, I-site effectors, FleQ, and Clp (reviewed in Hengge, 2009;Leduc and Roberts, 2009;Hickman and Harwood, 2008). In addition, cyclic-di-GMP in many bacterial species is sensed by a riboswitch RNA that controls the expression of genes involved in numerous cellular processes, including flagellar biosynthesis (Sudarsan et al., 2008). The cyclic-di-GMP signaling system is a member of two-component systems that are prevalent in bacteria and regulate diverse processes including virulence, adaptation, osmoregulation, and sporulation (Stock et al., 2000;Tobe, 2008;Ryndak et al., 2008).

Although the cyclic-di-GMP signaling system has been characterized in several types of bacteria, knowledge about this important signaling system is limited in spirochetes. Borrelia burgdorferi is the spirochete that causes Lyme disease. This spirochete must adapt to very different environments as it shuttles between arthropod Ixodes scapularis ticks and mammalian hosts. During transmission between hosts, B. burgdorferi modulates gene expression in response to environmental factors such as nutrient availability, pH, CO2, temperature, host factors, and immune pressure (Tilly et al., 2008;Rosa et al., 2005;Revel et al., 2002;Ojaimi et al., 2003;Brooks et al., 2003;Tokarz et al., 2004;Samuels and Radolf, 2009 and ref. therein). While two-component systems play important roles in the pathogenesis of many bacteria, only three two-component signaling systems have so far been reported in B. burgdorferi: hpk2-rrp2 (Yang et al., 2003), a chemotaxis system (Motaleb et al., 2005;Li et al., 2002;Fraser et al., 1997), and hpk1-rrp1 (Rogers et al., 2009;Galperin et al., 2001). Hpk2-Rrp2 has been characterized in detail and was found to govern B. burgdorferi virulence factors (Boardman et al., 2008;Ouyang et al., 2008;Burtnick et al., 2007) and to be important for mammalian infection (Boardman et al., 2008). Bioinformatics analysis suggests B. burgdorferi encodes a set of genes for a complete cyclic-di-GMP signaling system: a diguanylate cyclase (Rrp1, BB0419) containing a GGDEF domain; two putative PDEs, one (BB0363) containing an EAL/EIL domain and one (BB0374) containing an HD-GYP domain; and a cyclic-di-GMP-binding protein (BB0733) with a PilZ domain (Galperin et al., 2001; Amikam and Galperin, 2006;Rogers et al., 2009;Freedman et al., 2009). Rrp1 was shown to synthesize cyclic-di-GMP when phosphorylated in vitro (Ryjenkov et al., 2005). Our laboratory (unpublished results) and others (Freedman et al., 2009) demonstrated that BB0733 is a PilZ domain-containing protein that specifically binds to cyclic-di-GMP; bb0733 undergoes differential expression in different hosts (Freedman et al., 2009). Furthermore, microarray studies with the diguanylate cyclase mutant in a non-infectious B. burgdorferi strain indicated that it modulated expression of a number of genes, many of which were virulence-associated, suggesting a role for cyclic-di-GMP during the B. burgdorferi infectious life cycle (Rogers et al., 2009).

In this communication, we systematically characterized a putative PDE, BB0363. Enzymatic analysis confirmed that the BB0363 protein specifically hydrolyzes cyclic-di-GMP to pGpG. bb0363 was inactivated using new promoterless antibiotic resistance cassettes we developed that do not affect downstream gene expression. Inactivating bb0363 resulted in spirochetes with altered motility, and these mutants were unable to infect mice, but were able to survive in tick guts. Complementing the mutant cells restored normal motility and murine infectivity. These results demonstrate that cyclic-di-GMP signaling is important for B. burgdorferi motility and virulence. Furthermore, a mechanism by which cyclic-di-GMP may impact motility and virulence is discussed.

Results

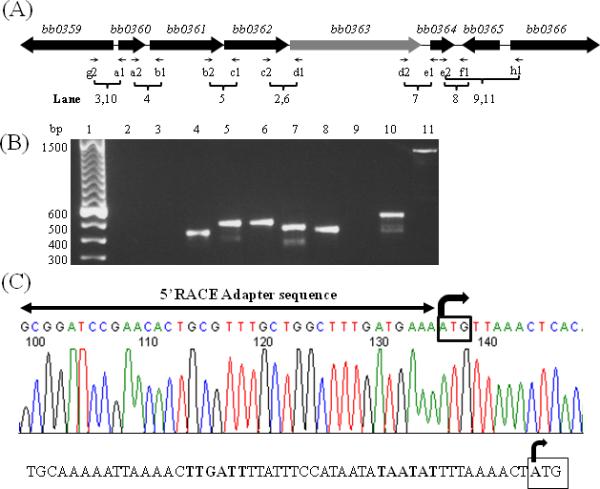

bb0363 is cotranscribed with four other genes in an operon

The B. burgdorferi genes bb0360, bb0361, bb0362, bb0363 and bb0364 are oriented in the same direction on the chromosome (Fig. 1A) (Fraser et al., 1997). In this region, bb0360 is separated from bb0361 by 4 bp, there is no intergenic space between bb0361--bb0362, bb0362 is separated from bb0363 by 21 bp, and bb0363 is separated from bb0364 by 94 bp. bb0360 encodes a putative hypothetical protein, bb0361 is predicted to encode an ATP-binding protein, bb0362 encodes a prolipoprotein diacylglyceryl transferase, bb0363 encodes a phosphodiesterase, and bb0364 encodes a methylglyoxal synthase (Fraser et al., 1997;Galperin et al., 2001). To determine the operon structure of these genes, RT-PCR was performed with total RNA using gene-specific primers (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1B, PCR products bridging the junction of bb0360 and bb0361 (lane 4), bb0361 and bb0362 (lane 5), bb0362 and bb0363 (lane 6), bb0363 and bb0364 (lane 7) were obtained as expected. However, with RNA as a template, we failed to amplify the region between bb0360-bb0359, indicating these two genes are divergently transcribed as expected and that bb0359 is not part of the bb0360-bb0364 operon (lane 3). A “no reverse transcriptase” reaction (lane 2) did not generate a PCR product, confirming RNA preparations were free of DNA. These results indicated that bb0360-bb0364 is transcribed as a polycistronic mRNA. Unexpectedly, we obtained a RT-PCR product using primer set e2-f1 (bb0364-bb0365) (lane 8). The bb0365 gene operon promoter and transcription start site (TSS) have been reported (von Lackum et al., 2007), and transcription is in the opposite direction of the bb0360 operon. Detecting a RT-PCR product with primer set e2-f1 is likely due to transcription of the bb0360 operon past bb0364 as transcription termination is not well understood in B. burgdorferi. To verify this result, another primer, f2, which binds upstream of primer f1 within the bb0365 coding sequence, was used with primer e2 in RT-PCR (bb0364-bb0365): a product was also obtained (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

bb0363 gene operon structure. (A). Schematic representation of the bb0360 operon. Thin arrows indicate specific primer pairs that amplify a region between genes. Lanes represent RT-PCR results shown in (B). Lanes 3 and 10 represents RNA and genomic DNA templates, respectively. Lane 2 no RT control. Lanes 9 and 11 represents RNA and genomic DNA templates, respectively. All other lanes used cDNA template that was converted from RNA template. (C). DNA sequencing chromatogram of an RLM-RACE analysis resulted in identification of a transcription start site (TSS) of bb0363 operon that is leaderless (right-angled arrow). The bb0360 ATG start codon is boxed. A horizontal line with arrowheads represents 5’-RACE adapter sequence (provided by the kit). Bottom-predicted promoter of bb0360 operon with the -10 and -35 sequences are indicated by bold font; TSS is indicated with a right angled arrow where bb0360 ATG start site is boxed.

Table 1.

RT-PCR primers used to determine the bb0360 operon structure.

| BB0359RT | (g2) | GATTGAAATATTCCTTTTAAAG |

| BB0360RT | (a1) | CCATGAAAAATTCAGGTGAGT |

| BB0360RT1 | (a2) | GTTAACATTTATCTTATACTCACCTG |

| BB0361RT | (b1) | AGATCAACAAGCAATACGCT |

| BB0361RT1 | (b2) | TTGAAGATTTAACAAATGATGCC |

| BB0362RT | (c1) | CAAGTGAGAACATGAATATTTCA |

| BB0362RT1 | (c2) | CTTCTCAACTTATTGAAGGATTT |

| BB0363RT | (d1) | GAGATCTCTAAGTCCAACTTCTT |

| BB0363RT1 | (d2) | AAGCTAGCACTTGATGACTTT |

| BB0364RT | (e1) | TTATCGTGTGCAATTAATGC |

| BB0364RT1 | (e2) | AAATCCAACAAGCTACCGAT |

| BB0365RT | (f1) | TTCAGATGCCAAGACCTTCC |

| BB0365RT1 | (h1) | GTAACTTTCAGAAAAATTTAAAATTTGATT |

To map a TSS of the bb0360-bb0364 operon, 5′-RLM-RACE analysis was performed. The TSS was determined as the first nucleotide of the ATG start codon of bb0360, suggesting that the operon is transcribed as a leaderless mRNA (Fig. 1C). To validate our RACE result, we determined the TSS of the flaB (bb0147) gene. A TSS of the flaB monocistronic operon has been reported using a primer extension assay (Ge et al., 1997). Our RLM-RACE results identified the same nucleotide as the flaB TSS (Ge et al., 1997).

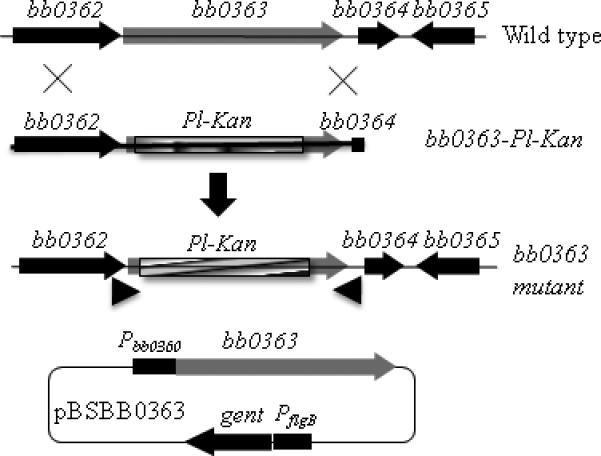

Refinement of antibiotic resistance cassettes and inactivation of bb0363

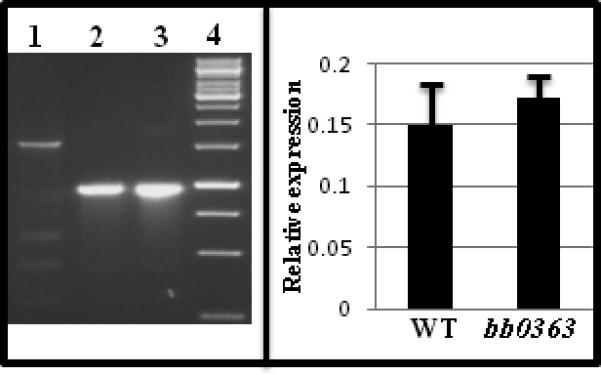

Insertion mutagenesis using an antibiotic resistance cassette as a selectable marker may cause a polar effect on genes downstream from the targeted gene (see Hyde et al., 2009;Li et al., 2002;Liu et al., 2009 for examples). Because of the polar effect, interpretation of results obtained from such mutants is complicated. Previously investigators have used B. burgdorferi flgB or flaB promoter-kanamycin/streptomycin/gentamicin cassettes (PflgB-Kan/Strep/Gent) to inactivate genes (reviewed in Rosa et al., 2005). We hypothesized that use of a cassette without a promoter might decrease the probability of inducing polar effects. Accordingly, we developed Pl-Kan and Pl-Strep cassettes by deleting the promoter sequence from PflgB-Kan and PflgB-Strep, keeping the ribosomal binding site intact (Bono et al., 2000). We also expected that inserting a heterologous gene (encoding antibiotic resistance) with a native ribosomal binding site within an operon should allow for its expression. To test our hypothesis, we constructed a bb0363 inactivation plasmid by inserting Pl-Kan within the bb0363 gene in-frame, using allelic exchange, to minimize any alterations to downstream genes (Fig. 2). As can be seen in Fig. 3 (left panel), PCR analysis confirmed that the bb0363 gene was inactivated. To assess whether insertion of Pl-Kan within bb0363 exerted an unexpected polar effect on the expression of gene bb0364 (immediately downstream from bb0363), qPCR was conducted. Results indicated that expression of bb0364 was not altered in the bb0363 mutant (Fig. 3, right panel).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of bb0363 inactivation and complementation. Insertion of the Pl-Kan cassette within bb0363 gene by homologous recombination resulted in the creation of bb0363 mutant. Approximate locations of one of the primer sets are shown by arrowheads that were used to confirm the bb0363 inactivation. Complementation plasmid pBSBB0363 containing the bb0360 promoter (Pbb0360) that drives the expression of bb0363 gene was used to complement the bb0363 mutant.

Fig. 3.

Confirmation of bb0363 inactivation and assessment of polar effect. Left panel - PCR was used to confirm the integration of Pl-Kan within the bb0363 gene. Location of PCR primers were shown in Fig. 2. An 892-bp DNA containing the Pl-Kan cassette was inserted after deleting a 1442-bp fragment from the bb0363 gene. Lane 1, wild-type (1546 bp); lane 2, bb0363::Pl-Kan (957 bp); lane 3, bb0363::Pl-Kan (957 bp) DNA that was electroporated into the wild-type cell (positive control); Lane 4, 1 Kb DNA ladder (Fermentas Life Sci). Right panel - lack of a polar effect on bb0364 expression in bb0363 mutant cells was detected by qPCR. The Bar represents the mean + SEM from two independent experiments. WT, wild type.

Numerous (at least 100) bb0363::Pl-Kan clones were obtained in the infectious B31-A3 background strain; several of these were characterized and found to exhibit identical genotypes and phenotypes, and one of these clones was used for subsequent analysis.

Complementation of bb0363 mutant

To complement the bb0363 mutant, we PCR amplified the bb0363 gene and its promoter (Pbb0360; 300 bp upstream of the bb0360-bb0364 operon) and fused them such that the promoter Pbb0360 drives expression of bb0363 from the shuttle vector pBSV2G (Fig. 2, bottom) (Jewett et al., 2009;Motaleb et al., 2007). Electroporation of the shuttle vector (pBSBB0363; Fig. 2, bottom) into the bb0363 mutant cells yielded >20 positive clones. The integrity and presence of the shuttle vector in the complemented cells was confirmed by PCR as well as by rescuing the vector from the complemented bb0363+ cells. To investigate expression of bb0363 in B. burgdorferi strains, qRT-PCR employing specific primers was performed to determine the level of bb0363 transcripts. As expected, bb0363 transcripts were detected in the wild type but not in the mutant cells; bb0363 transcripts in complemented bb0363+ cells were elevated about fivefold higher than the level in wild-type cells, indicating overexpression from the vector (data not shown; see below). PCR analysis indicated that all 20 of the endogenous plasmids found in the wild-type cells were retained in the bb0363 mutant and the complemented bb0363+ cells (see Supplemental Fig. S1).

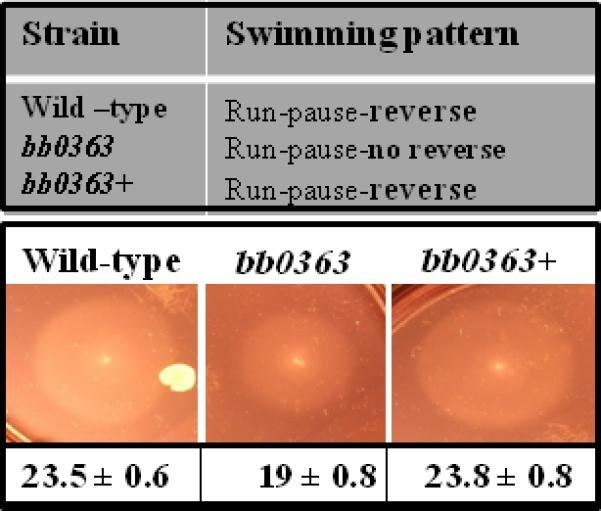

Analysis of bb0363 mutant phenotype

Inactivating cyclic-di-GMP metabolizing enzymes altered motility in several species of bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae and enteric Escherichia coli/Salmonella enterica (Pesavento et al., 2008;Ryjenkov et al., 2006;Tamayo et al., 2005;Tamayo et al., 2007;Pratt et al., 2007;Wolfe and Visick, 2008). To determine if a mutation in bb0363 altered B. burgdorferi motility, the mutant cells were video recorded and swarm plate motility assays were performed (Fig. 4) (Motaleb et al., 2007;Motaleb et al., 2000). As indicated in Fig. 4 (top panel), the wild-type cells ran, paused (stop/flex) and reversed direction, whereas the bb0363 cells ran and paused but failed to reverse direction. In swarm plate assays, the mutants swarm diameters were smaller than the wild-type cells, confirming a defect in motility (Fig. 4, middle and bottom panels). As expected, the complemented bb0363+ cells exhibited the wild-type pattern of motility and, in swarm plate assays, wild-type diameters were observed in the complemented bb0363+ cells (Fig. 4). Together, these results indicate that the bb0363 phenotype was solely attributed to inactivating the bb0363 gene and not due to a secondary alteration or a polar effect. Furthermore, in vitro growth studies demonstrated that bb0363 mutant cells, wild-type and complemented cells grew at the same rate, eliminating the possibility that phenotypic differences were attributed to different rates of growth between the clones (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Dark-field microscopy, video analysis and swarm plate motility assays confirmed that bb0363 was defective in motility. bb0363 mutant cells constantly ran-paused-ran in the same direction and failed to reverse swimming direction (top panel). Swarm diameters from four independent assays were measured in millimeter ± standard deviation (bottom). A representative swarm assay is shown (middle panel).

BB0363 is a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase

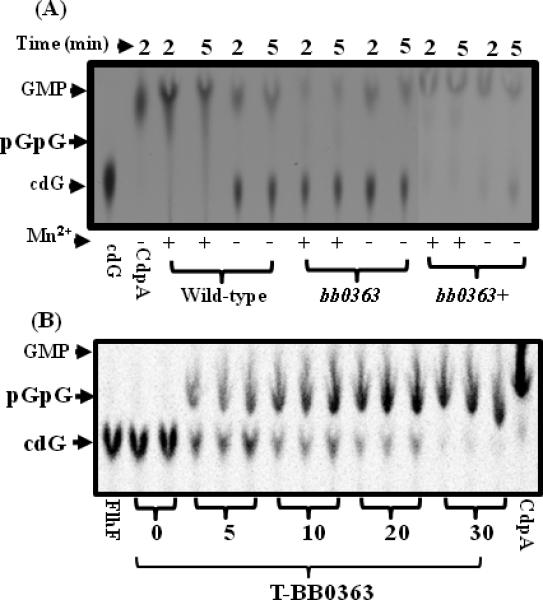

Analysis of the B. burgdorferi genome sequence suggested a single putative cyclic-di-GMP hydrolyzing PDE (BB0363) containing an EIL functional domain (EAL domain Pfam entry PF00563) (Galperin et al., 2001;Schmidt et al., 2005). In several species of bacteria, EAL/EIL domain-containing proteins have been shown to hydrolyze cyclic-di-GMP (Tamayo et al., 2005;Tamayo et al., 2008;Kulasakara et al., 2006;Schmidt et al., 2005). Furthermore, an active B. burgdorferi diguanylate cyclase (BB0419) has been reported (Rogers et al., 2009;Ryjenkov et al., 2005), suggesting one or more cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterases will also be expressed in B. burgdorferi. To determine if BB0363 is a cyclic-di-GMP PDE, PDE assays were performed with [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP and cyclic-di-GMP, and metabolites were separated by thin layer chromatography (TLC) (Tamayo et al., 2005;Christen et al., 2005).

Radiolabeled cyclic-di-GMP was synthesized from [33P]-GTP using purified recombinant Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclase WspR, as described (Lai et al., 2009;Kulasakara et al., 2006). Purified (greater than 90%) recombinant truncated-BB0363 (T-BB0363) as well as crude cell extracts prepared from wild-type, bb0363 mutant and bb0363+ complemented cells were tested for their ability to hydrolyze [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP. As shown in Fig. 5A, the wild-type crude extract rapidly hydrolyzed cyclic-di-GMP to GMP, indicating PDE activity (24.32 ± 1.6 pmol/mg min). Addition of MnCl2 to the reaction enhanced the PDE activity (compare ‘+’ and ‘-‘ lanes in Fig. 5A), as expected (Tamayo et al., 2005). bb0363 mutant extracts also hydrolyzed cyclic-di-GMP to GMP, but at a lower rate (6.0 ± 0.07 pmol/mg min) than wild-type extracts (Fig. 5A, lanes bb0363), suggesting more than one PDE is present in B. burgdorferi. bb0363+ complemented cell extracts rapidly hydrolyzed [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP (228.9 ± 36.8 pmol/mg min) (lanes bb0363+), indicating the reduction of [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP hydrolysis in bb0363 mutant cells was restored upon complementation. bb0363+ cell extracts exhibited greater than wild-type PDE activity, likely because bb0363 was overexpressed in the complemented cells. To confirm that BB0363 is a PDE, purified T-BB0363 was assayed for [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP hydrolysis. The truncated recombinant protein hydrolyzed [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP to pGpG (Fig. 5B), and the addition of MnCl2 enhanced the PDE activity, as expected (Fig. 5B), establishing that BB0363 is a cyclic-di-GMP PDE. T-BB0363 was assayed with different concentrations of [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP, and the Km was calculated to be 0.054 μM, consistent with other reports (Tamayo et al., 2005 and ref. therein) and indicating a high affinity for cyclic-di-GMP. The Rf values for the three nucleotides in these assays (cyclic-di-GMP = 0.37; GMP = 0.62; pGpG= 0.47) agree well with published reports (Tamayo et al., 2005;Tamayo et al., 2008). The positive control CdpA rapidly hydrolyzed cyclic-di-GMP to GMP (Tamayo et al., 2008) and negative controls without added protein or with an unrelated MBP-FlhF protein failed to hydrolyze cyclic-di-GMP (Fig. 5A, 5B). [3H]-cGMP was not hydrolyzed by T-BB0363 even upon prolonged incubation (overnight) (not shown), suggesting the PDE activity of T-BB0363 is specific for cyclic-di-GMP.

Fig. 5.

bb0363 exhibits phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity. (A), a representative TLC chromatogram of the PDE assay is shown. cdG represents cyclic-di-GMP. Plus and minus signs indicate presence or absence of 50 mM MnCl2. All reactions contained 5 mM MgCl2. A V. cholerae PDE CdpA was used as a positive control. Wild-type, bb0363 and bb0363+ refer to extracts of the corresponding cells. (B), a representative time course (0 to 30 minutes) TLC assay of the purified truncated bb0363 protein (T-bb0363) is shown. All lanes contained MnCl2 except the positive control CdpA. A maltose binding protein MBP-FlhF was used as a negative control (lane FlhF).

bb0363 mutant cells are unable to establish an infection in mice

In other bacteria, mutating cyclic-di-GMP-phosphodiesterase results in attenuation of virulence (Tamayo et al., 2005;Hengge, 2009;Kulasakara et al., 2006). To evaluate the ability of bb0363 cells to establish an infection in a mammalian host, C3H/HeN mice were needle inoculated by intraperitoneal plus subcutaneous (i.p. + s.c.) injection with 5×103 wild-type, bb0363::Pl-Kan or the isogenic complemented bb0363+ cells. Two weeks post inoculation, the mice were bled and their sera were assessed for reactivity with B. burgdorferi antigens. B. burgdorferi membrane protein A (BmpA), also known as P39, was used as a marker for infection in animals (Simpson et al., 1991;Jewett et al., 2007). None of the 7 mice inoculated with bb0363 mutant spirochetes showed evidence of seroconversion, while 7 out of 7 mice infected with wild-type or the complemented bb0363+ spirochetes did seroconvert (data not shown; see Table 2). Furthermore, intravenous (i.v.) inoculation of 5×103 cells into the tail vein of mice resulted in seroconversion with wild-type and bb0363+ cells, but not with bb0363 cells (Table 2). To confirm the serological results, mice were sacrificed 4 weeks post inoculation and tissue samples (ear, joint and bladder) were aseptically isolated and assessed for the presence of B. burgdorferi (Table 2). Whereas wild-type and complemented bb0363+ cells were reisolated from all tissues, demonstrating these cells established an infection, the bb0363 mutant cells were not isolated from any tissues.

Table 2.

Mouse and tick-mouse infectious studies.

| Strain | Dose | Route | Serology | Culture positive/specimens examined | Mice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ear | joint | bladder | Total | infected# | ||||

| Wild-type | 5 × 103 | ip+sc | 7/7 | 6/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 20/21 | 7/7 |

| bb0363 | 0/7 | 0/7 | 0/7 | 0/7 | 00/21 | 0/7 | ||

| bb0363+ | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 21/21 | 7/7 | ||

| Wild-type | 5 × 103 | tail vein | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 9/9 | 3/3 |

| bb0363 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/9 | 0/3 | ||

| bb0363+ | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 9/9 | 3/3 | ||

| Wild-type | 1 × 107 | ip+sc | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 9/9 | 3/3 |

| bb0363 | 3/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/9 | 0/3 | ||

| bb0363+ | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 9/9 | 3/3 | ||

| Wild-type | tick bite * | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 12/12 | 4/4 | |

| bb0363 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 00/12 | 0/4 | ||

| bb0363+ | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 12/12 | 4/4 | ||

Based on total number of mice infected with low and high doses, the P-value calculated by Fisher's Exact Test was 0.001.

Tick bite results are collected from two independent studies.

Mice were then inoculated with 1 × 107 cells/mouse, a very high inoculum (Table 2). Although inoculation of this high dose resulted in seroconversion in all mice, only complemented bb0363+ and the wild-type cells were able to establish an infection (Table 2). The plasmid profile of cells used to infect mice, as well as of spirochetes reisolated from mouse tissues were determined; in no instance was plasmid loss detected.

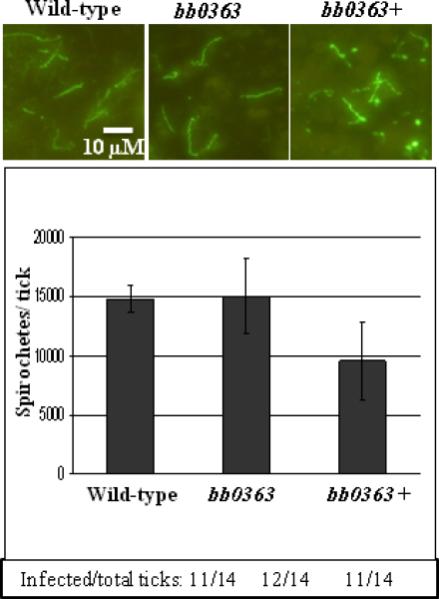

bb0363 is not required for B. burgdorferi survival within the tick host

The B. burgdorferi infectious life cycle includes persistent infection of and survival within tick and mammalian hosts. Because bb0363 mutant cells were unable to establish an infection in mice by needle inoculation, it was not possible to assess the ability of these cells to infect naïve ticks that feed on infected mice. Therefore, Ixodes scapularis tick larvae were artificially inoculated by tick-immersion with the wild-type, bb0363 mutant, or complemented bb0363+ cells; this resulted in infection of ticks with all strains (Fig. 6). The infected ticks were then allowed to feed on naïve mice and, five to seven days after ticks dropped off the mice, tick midguts were examined for the presence of spirochetes by indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA). As shown in Fig. 6 (top panel), the wild-type, bb0363 mutant and complemented bb0363+ cells were abundant in the ticks, demonstrating that the mutant cells were able to colonize ticks and survive within tick midguts after a blood meal.

Fig. 6.

IFA (Top panel). bb0363 spirochetes are able to survive before and after a blood meal from naïve mice. Spirochetes from indicated strains were detected by IFA in fed ticks (top). Total number of spirochetes per fed tick (5 ticks/strain + SEM) (middle). Tick infection frequency was determined by squashing ticks 7 days post feeding in BSK-II growth medium (bottom).

Ticks infected with PDE mutant cells are unable to infect mice

In the normal B. burgdorferi infectious cycle, mice are infected when spirochete-laden ticks bite them. We determined whether artificially infected ticks are able to transmit the infection after feeding on naïve mice. Whereas ticks colonized with wild-type or complemented cells were able to infect naïve mice (determined by serology and reisolation of spirochetes) ticks colonized with bb0363 mutant spirochetes were unable to seroconvert or to establish an infection in mice (Table 2, bottom). The inability of the bb0363 mutant-infected ticks to infect naïve mice was not due to a reduced number of B. burgdorferi per tick: the number of cells per fed tick was not significantly different between ticks immersed with wild-type, bb0363, or complemented bb0363+ cells (Fig. 6, bottom). With all strains, fed ticks contained ~1 × 104 spirochetes, as determined by plating triturated larvae and counting colony forming units (Fig. 6, middle panel), in good agreement with other reports (Battisti et al., 2008;Jewett et al., 2007). These results indicate that BB0363, a cyclic-di-GMP-hydrolyzing enzyme, is essential for B. burgdorferi infection of mice, irrespective of dose or route of inoculation (tick bite, i.v. or i.p. + s.c.).

Discussion

The objective of these studies was to investigate in detail a B. burgdorferi gene coding a putative cyclic-di-GMP PDE, bb0363. bb0363 is located in the bb0360-bb0364 operon. RLM-RACE studies suggest that the bb0360-bb0364 operon may be transcribed as a leaderless mRNA (Fig. 1). While two independent 5’-RACE analyses identified the same nucleotide as a TSS for the bb0360-bb0364 operon, there may be a second, upstream TSS that was not detected by 5’-RACE. Nonetheless, mechanisms for translation initiation involving leaderless transcripts are not uncommon in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes (Hering et al., 2009). When 300 base pairs upstream of the TSS was used to drive bb0363 gene expression from the shuttle vector in complemented bb0363+ cells, the level of transcripts was about fivefold higher than in wild type, indicating an active promoter. Overexpression of bb0363 in complemented cells may be attributed to the multi-copy nature of the pBSV2G shuttle vector (Frank et al., 2003). The overexpression of targeted genes is common when using this or pKFSS1 shuttle vectors (Motaleb et al., 2005;Seshu et al., 2006;Li et al., 2010). However, this level of overexpression did not appear to affect restoration of motility or infectivity in tick-mouse infections (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Several approaches were used to demonstrate that bb0363 encodes a functional PDE. For PDE assays, radiolabeled cyclic-di-GMP was synthesized using the P. aeruginosa diguanylate cyclase WspR instead of B. burgdorferi diguanylate cyclase, Rrp1 (BB0419) since Rrp1 requires phosphorylation to be activated in vitro (Ryjenkov et al., 2005). The use of a heterologous enzyme for the synthesis of cyclic-di-GMP has been reported (Lai et al., 2009;Simm et al., 2009). To demonstrate that BB0363 was a cyclic-di-GMP PDE, we attempted to express recombinant BB0363. We were unsuccessful in expressing full-length BB0363 or several other versions of BB0363. Some B. burgdorferi proteins have been difficult to express in E. coli (Riley et al., 2007;Smith et al., 2007), and there are reports of toxic effects of expressed proteins and/or failure to overexpress cyclic-di-GMP-metabolizing proteins in E. coli (Ryjenkov et al., 2005;Riley et al., 2007). The truncated version of BB0363 that we were able to express, T-BB0363, is a C-terminal fragment missing the first 385 amino acids (full-length BB0363 is 670 amino acids) and contains the EIL domain (aa 427-670) (Galperin et al., 2001). Truncated versions of PDEs containing the essential functional domain have been reported to retain enzymatic activity (Christen et al., 2005;Bobrov et al., 2005;Schmidt et al., 2005). Our PDE assays confirmed that T-BB0363 possesses enzymatic activity, with a Km of 0.054 μM, similar to that reported for other cyclic-di-GMP PDEs (Tamayo et al., 2005 and ref. therein). A PDE with an EAL/EIL domain hydrolyzes cyclic-di-GMP to pGpG whereas non-specific PDEs (PDE-B) or HD-GYP containing PDEs convert cyclic-di-GMP to GMP or pGpG to GMP (Tamayo et al., 2005;Ross et al., 1987). pGpG was not detected when B. burgdorferi crude extracts were incubated with 33P-[cyclic-di-GMP] (Fig. 5A), suggesting the presence of HD-GYP phosphodiesterase or PDE-B. In addition, a PDE assay of wild-type cell extracts resulted in hydrolysis of essentially all cyclic-di-GMP (Fig. 5A). In contrast, hydrolysis of cyclic-di-GMP was reduced, but not abolished, in bb0363 cell extracts, suggesting BB0363 was an active PDE, but was not the only PDE in B. burgdorferi.

A motility defect due to inactivation of the bb0363 cyclic-di-GMP PDE (Fig. 4) is consistent with similar mutants in other bacteria (Tamayo et al., 2005;Wolfe and Visick, 2008;Pesavento et al., 2008), but the mechanism by which inactivating bb0363 induces altered motility in B. burgdorferi is currently unknown. Cyclic-di-GMP can impact motility in a variety of ways: by affecting transcription of flagellar genes or assembly of flagella, or by interfering with flagellar motor function (Wolfe and Visick, 2008). Recently, a microarray with B. burgdorferi diguanylate cyclase bb0419 mutant indicated modulation of motility and chemotaxis gene expression, implying the importance of cyclic-di-GMP in regulating motility (Rogers et al., 2009). Cyclic-di-GMP is reported to affect the motility of some bacteria by influencing a hierarchical gene regulatory cascade involving σ28 (Wolfe and Visick, 2008;Beyhan et al., 2006;Girgis et al., 2007). However, genome sequence analysis indicated that a homologue for σ 28 or anti-sigma factor FlgM is not present in B. burgdorferi, and all motility and chemotaxis genes identified to date are reported to be driven by σ 70 promoters (Charon and Goldstein, 2002). Cyclic-di-GMP in many bacterial species is sensed by a riboswitch RNA that controls the expression of genes involved in numerous cellular processes, including flagellar biosynthesis. Such a riboswitch RNA does not appear to be present in B. burgdorferi (Sudarsan et al., 2008); however, a novel riboswitch cannot be excluded. Furthermore, in Caulobacter crescentus motility is affected by binding of cyclic-di-GMP to a PilZ receptor protein, causing a PilZ conformational change, and the cyclic-di-GMP-PilZ receptor complex then binds to and destabilizes FliL, altering flagellar motor function without affecting flagellar gene expression (Christen et al., 2007;Wolfe and Visick, 2008). Our laboratory (unpublished data) and others (Freedman et al., 2009) demonstrated that B. burgdorferi BB0733 is a PilZ domain-containing protein that specifically binds to cyclic-di-GMP. However, fliL mutant B. burgdorferi cells exhibit somewhat reduced motility, but the swimming pattern is indistinguishable from wild-type cells (M. Motaleb, J. Pitzer, S. Sultan and J. Liu-manuscript in preparation). Therefore, the swimming pattern in bb0363 cells (the cells run and pause but do not reverse) is not likely mediated via FliL. An E. coli cyclic-di-GMP receptor PilZ protein YcgR (a BB0733 PilZ homologue) is a σ 28 regulator that was shown to interact with flagellar motor/switch proteins to alter motility in response to cyclic-di-GMP (Wolfe and Visick, 2008;Ko and Park, 2000;Paul et al., 2010;Boehm et al., 2010;Ryjenkov et al., 2006). The phenotype of bb0363 cells suggests that cyclic-di-GMP may impact a protein(s) responsible for switching flagellar motor rotation. The swimming pattern of bb0363 cells is similar to that of cheY3 mutant cells, which constantly run but do not reverse or flex (M. Motaleb and N. Charon-unpublished). In E. coli/S. enterica, CheY is a chemotaxis response regulator protein that when phosphorylated binds to a flagellar switch protein, FliM, causing flagellar rotation to switch from clockwise (cells tumble) to counterclockwise (cells run). cheY null-mutant cells therefore constantly run because they are unable to switch rotation of their flagella (reviewed in Silversmith and Bourret, 1999;Berg, 2003). Since bb0363 cells are unable to reverse direction we propose that the cyclic-di-GMP-receptor complex might alter the swimming pattern of B. burgdorferi by interfering with interactions between FliM and CheY3-P or by inhibiting CheY3 phosphorylation or by interfering with flagellar motor switch protein function (Boehm et al., 2010;Paul et al., 2010).

Several studies have implicated cyclic-di-GMP in regulating the virulence of some bacteria, including Xanthomonas campestris, Legionella pneumophila, Brucella melitensis, Bordetella pertussis, P. aeruginosa, Vibrio vulnificus, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Cotter and Stibitz, 2007;Dow et al., 2006;Ryan et al., 2007;Lai et al., 2009 and ref. therein). Furthermore, although constructed in a B. burgdorferi non-infectious strain, microarray studies indicate that diguanylate cyclase BB0419 regulates virulence-associated genes (Rogers et al., 2009). Therefore, the attenuated virulence observed with the phosphodiesterase bb0363 mutant cells (Table 2) is consistent with other reports. Intravital microscopy of B. burgdorferi in a mouse indicated that the ‘back-and–forth’ (run-reverse) movement of wild-type cells is important in transendothelial migration (Moriarty et al., 2008;Norman et al., 2008), which may contribute to the inability of bb0363 mutant cells to establish an infection in mice (Table 2). Other studies demonstrate that cyclic-di-GMP can impact bacterial motility and virulence. In V. cholerae, increasing cyclic-di-GMP by overexpressing vdcA was shown to activate biofilm formation, inhibit motility, and reduce mouse small intestine colonization (Beyhan et al., 2006;Tischler and Camilli, 2004;Tamayo et al., 2008). A mutation in V. cholerae vieA abolished cyclic-di-GMP hydrolytic activity, resulting in a lack of motility and reduced virulence in the classical biotype but not the El Tor biotype (Tamayo et al., 2008;Tischler and Camilli, 2005). These reports and our findings with bb0363 suggest that there is a link between cyclic-di-GMP, motility, and virulence (Tamayo et al., 2007). This report is the first to demonstrate an important role of cyclic-di-GMP in both motility and virulence in the Lyme disease spirochete; further investigations are warranted to decipher the diverse roles of this important signaling molecule in B. burgdorferi.

In addition, we have refined and improved the available antibiotic resistance cassettes so that B. burgdorferi genes can be inactivated without causing polar effects on downstream gene expression (Rosa et al., 2005;Hyde et al., 2009;Li et al., 2002;Liu et al., 2009). Recently, Samuels and colleagues modified these cassettes to minimize polar effects on downstream gene expression from transcriptional read-through by adding a T7 transcriptional terminator (Dresser et al., 2009). Using the Pl-Kan (or Pl-Strep) cassettes described in this study, we have inactivated six genes that are internal or the first gene of four different operons and in no instance have polar effects been detected (Fig. 3 and unpublished results). In the modified cassettes, promoter activity is likely abolished by deleting the flgB promoter while maintaining the ribosome binding site; the level of resistance to antibiotics is maintained (200 μg/ml kanamycin or 80 μg/ml streptomycin) and similar to that of PflgB-Kan or PflgB-Strep (PflgB-aadA) cassettes (Frank et al., 2003;Bono et al., 2000) reducing the probability of spontaneous antibiotic-resistant mutants. The gene inactivating system described herein should be applicable to any bacteria.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Low-passage, virulent B. burgdorferi strain B31-A3 is used as a wild type throughout the study (Elias et al., 2002). The genome of the virulent B31 strain has been sequenced and was found to contain a total of 21 plasmids with 12 linear and 9 circular plasmids in addition to its 900 kbp linear chromosome (Fraser et al., 1997;Casjens et al., 2000). The clone B31-A3 of B31 lost circular plasmid 9 (cp9) and remains infectious in tick-mouse cycle studies (Elias et al., 2002;Jewett et al., 2009). B. burgdorferi were cultured in liquid Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly (BSK-II) medium as described (Elias et al., 2002;Jewett et al., 2009); plating BSK-II was prepared using 0.6% agarose. Swarm plate assays were carried out using 0.35% agarose; approximately 1 × 106 washed cells in 5 μl were spotted onto plates containing plating BSK-II medium diluted 1:10 in Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (PBS) without divalent cations. Since B. burgdorferi is a slow-growing organism with 8-12 hours generation time, swarm plates were incubated for 4 days (Motaleb et al., 2000;Motaleb et al., 2007).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), RNA Ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE), and qPCR

Exponentially growing B. burgdorferi B31-A3 cells (2 × 107 cells/ml) were treated with RNAprotect™ followed by total RNA isolation using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc.). Contaminating DNA in the RNA samples was removed by RNase-free Turbo® DNase I (Ambion Inc.) digestion for 3 hours at 37°C followed by RNeasy mini purification. For RT-PCR, cDNA was prepared from 1 μg RNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen Inc.). RT-PCR primer sequences are shown in Table 1. To determine the transcription start site of the phosphodiesterase gene (bb0363) operon, 5’- RLM-RACE was performed using 2 μg purified total RNA and a bb0360 gene-specific primer (BB0360-RT; a1) (Table 1) according to the manufacturer's protocol (Ambion Inc.). RLM-RACE PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega Inc.) followed by DNA sequencing. As a positive control, the same procedure was used to determine the transcription start site of the monocistronically transcribed flaB gene operon (Ge et al., 1997) using a flaB gene specific primer 5’-CTTCATTTAAATTCCCTTCTGTT-3’.

A Bio-Rad cDNA synthesis kit and iCycler detection system was used to measure the bb0364 transcript level in wild-type and bb0363 mutant cells according to manufacturer's instructions. B. burgdorferi enolase was used a reference gene (Motaleb et al., 2004). The gene specific primers (5’-3’) were RT-BB0364-F (TATTGCAACAGGAACAACGGGG) and RT-BB0364-R (GCTGGCTTGTTAGGGGATCC); and RT-enolase-F (TGGAGCGTACAAAGCCAACATT) and RT-enolase-R (TGAAAAACCTCTGCTGCCATTC). The relative level of expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001;Simm et al., 2009).

Construction of a bb0363 mutant

Targeted inactivation of bb0363 (a 2013-base pairs gene) was achieved by homologous recombination using a promoterless Pl-Kan cassette. The Pl-Kan cassette contains the ribosomal binding site and transcription start point of the B. burgdorferi flgB promoter (PflgB) followed by the kanamycin resistance gene (Bono et al., 2000). PCR amplification of bb0363, construction of the inactivation plasmids, and electroporation of linear bb0363-Pl-Kan DNA into competent cells were carried out as described previously (Motaleb et al., 2005;Motaleb et al., 2007;Samuels et al., 1994). Briefly, bb0363 DNA was PCR-amplified using the Expand Long PCR system (Roche Inc.) and primers (5'-3') BB0363-KO-F (ACATAAATTACCCAAGTTGG) and BB0363-KO-R (TTATCGTGTGCAATTAATGC) and then ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), yielding pBB0363-Easy. Pl-Kan was similarly PCR-amplified from PflgB-Kan (Bono et al., 2000) using primers (5’-3’) PrLs Kan Hind-F (AAGCTTTAGTTAAAAGCAAT) and PrLs Kan Hind-R (AAGCTTTTAGAAAAACTCAT). The HindIII-restricted Pl-Kan DNA was then inserted into the HindIII sites within bb0363 (located 80 and 1522 base pairs from the bb0363 ATG start codon) of the pbb0363-Easy vector, yielding pbb0363-Pl-Kan. This deletion–insertion was in-frame. Restriction mapping indicated that the direction of transcription of Pl-Kan was the same as that of bb0363. bb0363-Pl-Kan was digested and separated from pbb0363-Pl-Kan vector by NotI and precipitated for electroporation into strain B31-A3 competent cells (Motaleb et al., 2007). Mutants were selected on solid growth medium containing 200 μg/ml kanamycin. Resistant colonies were analyzed by PCR for the presence of the Pl-Kan cassette using primers PrLs Kan Hind-F and –R as well as using primers (5’-3’) BB0363 scr-F (ATCTCTAAAAAAGAAGTTGGAC) and BB0363 scr-R (TGGGATTTTAGTGAATAAGG). PCR-positive mutants were further examined for their plasmid contents using 21 sets of primers to detect 21 linear and circular plasmids (Zhou et al., 2008).

Complementation of bb0363 mutant

To complement bb0363::Pl-Kan, the promoter of bb0360 operon (Pbb0360; 300 bp upstream from the ATG start codon of bb0360) was PCR-amplified using overlapping PCR with primers (5'-3') BB0363pr.com-F (GGATCCTCGCCTAGGGATTGAAAT) and BB0363pr.com2-R (GACTTTGTTCATAGTTTTAAAATATTATATTA). The coding sequence of bb0363 was PCR-amplified with primers BB0363.com2-F (AACTATGAACAAAGTCAATAATTATC) and BB0363.com-R (GGATCCTCACTTTTTTAGAATTTATA). BamHI sites are in bold font. The promoter and coding sequence were then amplified together by overlapping PCR using primers BB0363pr.com-F and BB0363.com-R. The PCR product was ligated into pGEM-T Easy. The bb0360 promoter-bb0363 (Pbb0360-bb0363) DNA was then inserted into shuttle vector pBSV2G (Jewett et al., 2009) using BamHI restriction digestion, yielding pBSBB0363. Ten micrograms of the resultant plasmid was electroporated into the bb0363:Pl-Kan competent cells. Transformants were selected on solid growth medium containing 200 μg/ml kanamycin and 40 μg/ml gentamicin. Resistant transformants were analyzed by PCR for the presence of kan and gent. The shuttle vector was also rescued from complemented bb0363+ cells, purified from E. coli, and used to confirm the integrity of the Pbb0360-bb0363. Positive transformants were further examined for their plasmid content by PCR.

BB0363 recombinant protein expression and phosphodiesterase (PDE) assays

Recombinant BB0363 protein was prepared by amplification of the coding sequence without the first 385 amino acid residues by PCR using primers (5’-3’) T-BB0363-F (GGATCCATAATAGAGGTAAATTTAAAAG) and T-BB0363-R (CTGCAGCTAATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGTATTGGTTCTGGTTTGTGCC) creating a BamHI and PstI site (underlined), respectively, and 6xHis at the C-terminal end (italics). The amplified DNA fragment was ligated into an E. coli expression vector pMAL c2X (New England Biolabs) using restriction sites 5’-BamHI and 3’-PstI. The vector was then digested and sequenced to confirm its integrity. E. coli cells containing the pbb0363-MAL were induced with 1 mM IPTG at 25°C for 4 hours and Ni2+-affinity purified. Purified truncated recombinant BB0363 (T-BB0363) protein was resolved in an SDS-PAGE to determine protein concentration and purity.

PDE assays using cell extracts, wild-type B31-A3, bb0363 mutant and complemented bb0363+ cell extracts were prepared as described (Christen et al., 2005). Briefly, cell pellets were washed once with PBS and resuspended in diguanylate cyclase buffer (250 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl and 10% glycerol). Lysed cells were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 hour and protein concentration in the supernatants determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit.

Synthesis of radiolabeled cyclic-di-GMP substrate for PDE assays was performed as described (Lai et al., 2009) and approved by the East Carolina University Radiation Safety Committee. An E. coli clone carrying Pseudomonas aeruginosa His6-WspR that has high diguanylate cyclase activity was affinity purified as described (Lai et al., 2009;Kulasakara et al., 2006). [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP was prepared by incubating 20 μg of His6-WspR, 100 μCi of [α-33P]-GTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; 10 mCi/ml; Perkin Elmer), and 80 pmol unlabeled GTP (Sigma-Aldrich) in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol for 4 hours at 25°C. The reaction was then incubated with 20 units of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (New England Biolabs) for an hour at 25°C to hydrolyze unreacted GTP. The reaction was stopped with 0.5 M EDTA and passed through an Ultrafree MC-5000 column (Millipore).

PDE assays were performed as described (Tamayo et al., 2005). T-BB0363 protein (2 μg) or crude extracts (4 μg) were incubated with [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP with or without 50 mM MnCl2 for different periods of times. A no enzyme/unrelated protein MBP-FlhF negative control and a Vibrio cholerae PDE His6-CdpA (1.5 μg) was used as a positive control (Tamayo et al., 2008). Reaction products (0.5 μl) were spotted and separated by TLC using polyethyleneimine-cellulose plates in 1.5 M KH2PO4, pH 3.65 buffer. The plates were air dried followed by phosphorimagery, and volume analysis using Image Quant TL v2003. The final concentration and yield of c-di-GMP were calculated based on the percent incorporation of [33P] GTP into [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP. To determine Km, T-BB0363 was incubated with 2 – 70 nM [33P]-cyclic-di-GMP for up to 30 minutes, reactions were stopped every 30 seconds and chromatographed on TLC as described (Tamayo et al., 2005;Christen et al., 2005); and results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5. To determine substrate specificity of T-BB0363, 15-30 nM 3H-[cGMP] (Perkin Elmer) was incubated with 6 μg of T-BB0363 for 30 minutes to >14 hours (overnight) and the reaction was separated in TLC as described (Tamayo et al., 2005).

Experimental mouse-tick model of B. burgdorferi life cycle

Three week old female C3H/HeN mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, NC and housed in the East Carolina University animal facility at the Brody School of Medicine according to the institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. For infection via needle, either 5×103 or 1×107 in vitro grown spirochetes were injected, 80% intraperitoneally and 20% subcutaneous ,or via tail vein injection as described (Elias et al., 2002;Jewett et al., 2007). The number of spirochetes was determined using a Petroff-Hausser chamber and verified by colony forming unit counts on plating BSK-II medium. Ten colonies from each clone were verified for their retention of lp25, lp28-1 and lp36 plasmids. For either inoculation scheme, mice were bled (retro-orbital) two weeks post infection for immunoblot analysis of mouse sera; and reisolation of B. burgdorferi from mouse skin, bladder, and joint tissues was performed four weeks post infection. Mouse tissues in the BSK-II growth medium were incubated for up to 35 days and the presence of spirochetes was determined by dark-field microscopy.

For tick infection studies, naïve Ixodes scapularis larvae were purchased from Oklahoma State University and the University of Rhode Island Center for Vector-Borne Diseases. Two independent experiments were performed with ticks obtained from these different sources. Ticks were kept at 23°C under a 14:10 light : dark photoperiod in a humidified chamber with 85-90% relative humidity. Approximately 400 larval ticks were artificially infected by immersion (in duplicate) in equal density exponential phase B. burgdorferi cultures as described (Stewart et al., 2008;Policastro and Schwan, 2003;Battisti et al., 2008), except larval ticks were equilibrated to a lower relative humidity before immersion to enhance spirochete uptake. Ticks were fed to repletion on separate naïve mouse for 5-7 days, allowed to fall off and collected. Subsets of larvae were dissected 7 days after repletion, and the isolated midguts were analyzed by immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for the presence of spirochetes (Stewart et al., 2008). Fed larvae were surface sterilized using 3% H2O2 followed by 70% ethanol, crushed in BSK-II medium and plated to determine the colony forming units per tick. Sera from mice obtained 2 weeks after tick-feeding were tested against B. burgdorferi antigens to determine infectivity, as described (Simpson et al., 1991;Elias et al., 2002;Rosa et al., 2005). Reisolation of spirochetes from mice ears, joints and bladders was performed as described (Elias et al., 2002;Stewart et al., 2008;Grimm et al., 2003) to assess the ability of spirochetes to infect mice. Reisolated clones were genotyped using PCR as described above.

Immunofluorescence assays

Ticks were dissected in 25 μl PBS-5 mM MgCl2 in Teflon-coated microscopic slides, mixed by pipetting, and then air dried. To avoid quenching by hemin in the blood, dissected tick contents were 10-fold serially diluted (P. Policastro, RML, NIH-personal communication). Slides were blocked with 0.75% BSA in PBS, 5 mM MgCl2 and washed with PBS-5 mM MgCl2. Spirochetes were detected using a 1:100 dilution of goat anti-B. burgdorferi antisera labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.). Images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Imager M1 microscope coupled with a digital camera.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We are indebted to D. S. Samuels for comments on the manuscript. We thank N. W. Charon for encouragement. We thank A. Camilli, V. T. Lee, D. S. Samuels and D. Akins for E. coli clones expressing CdpA, WspR, pKSSF1 plasmid and B. burgdorferi plasmids primer sequence information, respectively. We are indebted to the members of P. Rosa laboratory for providing reagents and helpful discussions toward setting up our tick-mouse facility and studies. We thank P. Policastro for his insightful discussions in tick-infectious studies. This research is supported by an American Heart Association grant 0755614B to M.R.M and National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin diseases, NIH grant R03AR054582 and an East Carolina University Research and Development startup fund to M.A.M.

References

- Amikam D, Galperin MY. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:3–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battisti JM, Bono JL, Rosa PA, Schrumpf ME, Schwan TG, Policastro PF. Outer surface protein A protects Lyme disease spirochetes from acquired host immunity in the tick vector. Infect Immun. 2008;76:5228–5237. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00410-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg HC. The Rotary Motor of Bacterial Flagella. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3600–3613. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3600-3613.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman BK, He M, Ouyang Z, Xu H, Pang X, Yang XF. Essential role of the response regulator Rrp2 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3844–3853. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00467-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrov AG, Kirillina O, Perry RD. The phosphodiesterase activity of the HmsP EAL domain is required for negative regulation of biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;247:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm A, Kaiser M, Li H, Spangler C, Kasper CA, Ackermann M, et al. Second Messenger-Mediated Adjustment of Bacterial Swimming Velocity. Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono JL, Elias AF, Kupko JJ, III, Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2445-2452.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CS, Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Akins DR. Global analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi genes regulated by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3371–3383. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3371-3383.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick MN, Downey JS, Brett PJ, Boylan JA, Frye JG, Hoover TR, Gherardini FC. Insights into the complex regulation of rpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:277–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, Rosa P, et al. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AL, Tuckerman JR, Gonzalez G, Mayer R, Weinhouse H, Volman G, et al. Phosphodiesterase A1, a regulator of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum, is a heme-based sensor. Biochem. 2001;40:3420–3426. doi: 10.1021/bi0100236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon NW, Goldstein SF. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: The Spirochetes. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:47–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.041602.134359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen M, Christen B, Allan MG, Folcher M, Jeno P, Grzesiek S, Jenal U. DgrA is a member of a new family of cyclic diguanosine monophosphate receptors and controls flagellar motor function in Caulobacter crescentus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4112–4117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607738104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen M, Christen B, Folcher M, Schauerte A, Jenal U. Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30829–30837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter PA, Stibitz S. c-di-GMP-mediated regulation of virulence and biofilm formation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow JM, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Ryan RP. The HD-GYP domain, cyclic di-GMP signaling, and bacterial virulence to plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:1378–1384. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser AR, Hardy PO, Chaconas G. Investigation of the genes involved in antigenic switching at the vlsE locus in Borrelia burgdorferi: an essential role for the RuvAB branch migrase. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000680. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerig A, Abel S, Folcher M, Nicollier M, Schwede T, Amiot N, et al. Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 2009;23:93–104. doi: 10.1101/gad.502409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias AF, Stewart PE, Grimm D, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Tilly K, et al. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: Implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2139–2150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2139-2150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineran PC, Williamson NR, Lilley KS, Salmond GP. Virulence and prodigiosin antibiotic biosynthesis in Serratia are regulated pleiotropically by the GGDEF/EAL domain protein, PigX. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:7653–7662. doi: 10.1128/JB.00671-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank KL, Bundle SF, Kresge ME, Eggers CH, Samuels DS. aadA confers streptomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6723–6727. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6723-6727.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman JC, Rogers EA, Kostick JL, Zhang H, Iyer R, Schwartz I, Marconi RT. Identification and molecular characterization of a cyclic-di-GMP effector protein, PlzA (BB0733): additional evidence for the existence of a functional cyclic-di-GMP regulatory network in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Nikolskaya AN, Koonin EV. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;203:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Old I, Saint Girons I, Charon NW. The flgK motility operon of Borrelia burgdorferi is initiated by a σ70 -like promoter. Microbiol. 1997;143:1681–1690. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-5-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis HS, Liu Y, Ryu WS, Tavazoie S. A comprehensive genetic characterization of bacterial motility. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1644–1660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Elias AF, Tilly K, Rosa PA. Plasmid stability during in vitro propagation of Borrelia burgdorferi assessed at a clonal level. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3138-3145.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering O, Brenneis M, Beer J, Suess B, Soppa J. A novel mechanism for translation initiation operates in haloarchaea. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1451–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman JW, Harwood CS. Identification of FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a c-di-GMP-responsive transcription factor. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69:376–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman JW, Tifrea DF, Harwood CS. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14422–14427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JA, Shaw DK, Smith IR, Trzeciakowski JP, Skare JT. The BosR regulatory protein of Borrelia burgdorferi interfaces with the RpoS regulatory pathway and modulates both the oxidative stress response and pathogenic properties of the Lyme disease spirochete. Mol Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06951.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenal U, Malone J. Mechanisms of cyclic-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:385–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett MW, Lawrence K, Bestor AC, Tilly K, Grimm D, Shaw P, et al. The critical role of the linear plasmid lp36 in the infectious cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:1358–1374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett MW, Lawrence KA, Bestor A, Byram R, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. GuaA and GuaB are essential for Borrelia burgdorferi survival in the tick-mouse infection cycle. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6231–6241. doi: 10.1128/JB.00450-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M, Park C. Two novel flagellar components and H-NS are involved in the motor function of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2000;303:371–382. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulasakara H, Lee V, Brencic A, Liberati N, Urbach J, Miyata S, et al. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3'-5')-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2839–2844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai TH, Kumagai Y, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Rikihisa Y. The Anaplasma phagocytophilum PleC histidine kinase and PleD diguanylate cyclase two-component system and role of cyclic Di-GMP in host cell infection. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:693–700. doi: 10.1128/JB.01218-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc JL, Roberts GP. Cyclic di-GMP allosterically inhibits the CRP-like protein (Clp) of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7121–7122. doi: 10.1128/JB.00845-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Bakker RG, Motaleb MA, Sartakova ML, Cabello FC, Charon NW. Asymmetrical flagellar rotation in Borrelia burgdorferi nonchemotactic mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6169–6174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092010499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Xu H, Zhang K, Liang FT. Inactivation of a putative flagellar motor switch protein FliG1 prevents Borrelia burgdorferi from swimming in highly viscous media and blocks its infectivity. Mol Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lin T, Botkin DJ, McCrum E, Winkler H, Norris SJ. Intact flagellar motor of Borrelia burgdorferi revealed by cryo-electron tomography: evidence for stator ring curvature and rotor/C-ring assembly flexion. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5026–5036. doi: 10.1128/JB.00340-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty TJ, Norman MU, Colarusso P, Bankhead T, Kubes P, Chaconas G. Real-time high resolution 3D imaging of the lyme disease spirochete adhering to and escaping from the vasculature of a living host. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000090. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb MA, Corum L, Bono JL, Elias AF, Rosa P, Samuels DS, Charon NW. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10899–10904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200221797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb MA, Miller MR, Bakker RG, Li C, Charon NW. Isolation and characterization of chemotaxis mutants of the Lyme disease Spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi using allelic exchange mutagenesis, flow cytometry, and cell tracking. Methods Enzymol. 2007;422:421–437. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)22021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb MA, Miller MR, Li C, Bakker RG, Goldstein SF, Silversmith RE, et al. CheX is a phosphorylated CheY phosphatase essential for Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7963–7969. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.7963-7969.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motaleb MA, Sal MS, Charon NW. The decrease in FlaA observed in a flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi occurs posttranscriptionally. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3703–3711. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3703-3711.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman MU, Moriarty TJ, Dresser AR, Millen B, Kubes P, Chaconas G. Molecular mechanisms involved in vascular interactions of the Lyme disease pathogen in a living host. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000169. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojaimi C, Brooks C, Casjens S, Rosa P, Elias A, Barbour A, et al. Profiling of temperature-induced changes in Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression by using whole genome arrays. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1689–1705. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.1689-1705.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Z, Blevins JS, Norgard MV. Transcriptional interplay among the regulators Rrp2, RpoN and RpoS in Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiol. 2008;154:2641–2658. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul K, Nieto V, Carlquist WC, Blair DF, Harshey RM. The c-di-GMP Binding Protein YcgR Controls Flagellar Motor Direction and Speed to Affect Chemotaxis by a “Backstop Brake” Mechanism. Mol Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R, Weiser S, Amiot NC, Chan C, Schirmer T, Giese B, Jenal U. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 2004;18:715–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.289504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesavento C, Becker G, Sommerfeldt N, Possling A, Tschowri N, Mehlis A, Hengge R. Inverse regulatory coordination of motility and curli-mediated adhesion in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2434–2446. doi: 10.1101/gad.475808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policastro PF, Schwan TG. Experimental infection of Ixodes scapularis larvae (Acari: Ixodidae) by immersion in low passage cultures of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:364–370. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.3.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt JT, Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12860–12870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revel AT, Talaat AM, Norgard MV. DNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression in Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1562–1567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032667699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley SP, Bykowski T, Babb K, von LK, Stevenson B. Genetic and physiological characterization of the Borrelia burgdorferi ORF BB0374-pfs-metK-luxS operon. Microbiol. 2007;153:2304–2311. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/004424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EA, Terekhova D, Zhang HM, Hovis KM, Schwartz I, Marconi RT. Rrp1, a cyclic-di-GMP-producing response regulator, is an important regulator of Borrelia burgdorferi core cellular functions. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1551–1573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa PA, Tilly K, Stewart PE. The burgeoning molecular genetics of the Lyme disease spirochaete. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:129–143. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross P, Weinhouse H, Aloni Y, Michaeli D, Weinberger-Ohana P, Mayer R, et al. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature. 1987;325:279–281. doi: 10.1038/325279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Crossman LC, Spiro S, He YW, et al. Cell-cell signaling in Xanthomonas campestris involves an HD-GYP domain protein that functions in cyclic di-GMP turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6712–6717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600345103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ryan RP, Fouhy Y, Lucey JF, Jiang BL, He YQ, Feng JX, et al. Cyclic di-GMP signalling in the virulence and environmental adaptation of Xanthomonas campestris. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:429–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RP, Lucey J, O'Donovan K, McCarthy Y, Yang L, Tolker-Nielsen T, Dow JM. HD-GYP domain proteins regulate biofilm formation and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1126–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryjenkov DA, Simm R, Romling U, Gomelsky M. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP: the PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30310–30314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:1792–1798. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1792-1798.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryndak M, Wang S, Smith I. PhoP, a key player in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels DS, Mach KE, Garon CF. Genetic transformation of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi with coumarin-resistant gyrB. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6045–6049. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.19.6045-6049.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels DS, Radolf JD. Who is the BosR around here anyway? Mol Microbiol. 2009;74:1295–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer T, Jenal U. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:724–735. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:4774–4781. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4774-4781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshu J, Esteve-Gassent MD, Labandeira-Rey M, Kim JH, Trzeciakowski JP, Hook M, Skare JT. Inactivation of the fibronectin-binding adhesin gene bbk32 significantly attenuates the infectivity potential of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1591–1601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silversmith RE, Bourret RB. Throwing the switch in bacterial chemotaxis. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:16–22. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simm R, Remminghorst U, Ahmad I, Zakikhany K, Romling U. A role for the EAL-like protein STM1344 in regulation of CsgD expression and motility in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JB.00290-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson WJ, Burgdorfer W, Schrumpf ME, Karstens RH, Schwan TG. Antibody to a 39-kilodalton Borrelia burgdorferi antigen (P39) as a marker for infection in experimentally and naturally inoculated animals. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:236–243. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.236-243.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AH, Blevins JS, Bachlani GN, Yang XF, Norgard MV. Evidence that RpoS (sigmaS) in Borrelia burgdorferi is controlled directly by RpoN (sigma54/sigmaN). J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2139–2144. doi: 10.1128/JB.01653-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PE, Bestor A, Cullen JN, Rosa PA. A tightly regulated surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi is not essential to the mouse-tick infectious cycle. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1970–1978. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00714-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsan N, Lee ER, Weinberg Z, Moy RH, Kim JN, Link KH, Breaker RR. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science. 2008;321:411–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1159519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo R, Pratt JT, Camilli A. Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:131–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo R, Schild S, Pratt JT, Camilli A. Role of cyclic Di-GMP during el tor biotype Vibrio cholerae infection: characterization of the in vivo-induced cyclic Di-GMP phosphodiesterase CdpA. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1617–1627. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01337-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. The EAL domain protein VieA is a cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33324–33330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506500200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly K, Rosa PA, Stewart PE. Biology of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:217–34. v. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischler AD, Camilli A. Cyclic diguanylate regulates Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5873–5882. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5873-5882.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobe T. The roles of two-component systems in virulence of pathogenic Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;631:189–199. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarz R, Anderton JM, Katona LI, Benach JL. Combined effects of blood and temperature shift on Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression as determined by whole genome DNA array. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5419–5432. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5419-5432.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lackum K, Ollison KM, Bykowski T, Nowalk AJ, Hughes JL, Carroll JA, et al. Regulated synthesis of the Borrelia burgdorferi inner-membrane lipoprotein IpLA7 (P22, P22-A) during the Lyme disease spirochaete's mammal-tick infectious cycle. Microbiol. 2007;153:1361–1371. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe AJ, Visick KL. Get the message out: cyclic-Di-GMP regulates multiple levels of flagellum-based motility. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:463–475. doi: 10.1128/JB.01418-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XF, Alani SM, Norgard MV. The response regulator Rrp2 is essential for the expression of major membrane lipoproteins in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11001–11006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834315100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Miller MR, Motaleb M, Charon NW, He P. Spent culture medium from virulent Borrelia burgdorferi increases permeability of individually perfused microvessels of rat mesentery. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.