Abstract

Drugs that inhibit brain dopamine transporters (DAT) have been developed as potential agonist medications for cocaine abuse and dependence. Because the mechanism of action of such drugs is similar to cocaine, one concern regarding their use is the abuse potential of the medications themselves. The present study compared the reinforcing strength of cocaine (0.003–0.3 mg/kg) and two 3-phenyltropane analogs of cocaine, RTI-336 (3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-2β-[3-(4’-methylphenyl)isoxazol-5-yl]tropane hydrochloride; 0.003–0.1 mg/kg) and RTI-177 (3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-2β-(3-phenylisoxazol-5-yl]tropane hydrochloride; 0.003–0.1 mg/kg), using a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule in rhesus monkeys (n=4). PR schedules of reinforcement are frequently used to measure reinforcing strength of drugs. Earlier research using limited-access conditions reported that cocaine was a stronger reinforcer than either RTI-336 or RTI-177. Because the 3-phenyltropanes have longer durations of action, one purpose of the present study was to examine reinforcing strength using longer experimental sessions. Under these conditions, cocaine functioned as a reinforcer in all monkeys, and RTI-336 and RTI-177 functioned as a reinforcer in three of four subjects. Consistent with their documented slower onset of neurochemical and pharmacological effects, RTI-336 and RTI-177 were weaker reinforcers, resulting in fewer injections than cocaine. On average, the potencies of the two RTI compounds were not different than that of cocaine. These results support the view that slow-onset DA-selective uptake inhibitors have lower abuse liability than cocaine. In addition, the present findings suggest that changes in PR session length can influence potency comparisons between drugs, but not measures of reinforcing strength.

Keywords: agonist medication, cocaine, dopamine, dopamine transporter, progressive-ratio schedule, self-administration, nonhuman primates

1. Introduction

Cocaine abuse persists as a major public health problem for which no pharmacotherapy has proven to be sufficiently effective (Vocci, 2005). Recently, the success of methadone and nicotine replacement therapies in the treatment of opiate and nicotine addiction, respectively, has encouraged efforts to develop an indirect dopamine agonist medication to treat stimulant abuse (Grabowski et al., 2004; Rothman and Glowa, 1995). Agonist therapies have pharmacological mechanisms and behavioral effects similar to those of the abused drug. Because the abuse-related behavioral effects of cocaine have been most consistently linked to inhibition of the dopamine (DA) transporter (DAT) and subsequent stimulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission (e.g., Bergman et al., 1989; Lile and Nader, 2003; Ritz et al., 1987), development of an indirect dopamine agonist medication for cocaine dependence has focused on drugs that activate brain DA systems by inhibiting DA uptake or enhancing DA release (Carroll et al., 1999; Howell and Wilcox, 2001; Platt et al., 2002; Rothman et al., 2005). Characteristics of an ideal indirect DA agonist therapy are thought to include high DAT binding affinity, high selectivity for the DAT versus serotonin and norepinephrine transporters (SERT and NET, respectively), an ability to reproduce the interoceptive stimulus effects of cocaine and the capacity to reduce cocaine self-administration by displacing the cocaine dose-effect curve downward (reviewed in Mello and Negus, 1996; Carroll et al., 1999). In addition, because the rapid rate of onset and short duration of the pharmacological effects of cocaine are understood to play an important role in its abuse liability (Stathis et al., 1995; Volkow et al., 1999), a slow onset and long duration of action are desirable pharmacological properties of an indirect dopamine agonist medication.

Over the past two decades, several 3-phenyltropane analogs of cocaine that display high affinity and selectivity for the DAT have been synthesized and examined in laboratory animal models of cocaine abuse (for review see Carroll et al., 1999; Carroll, 2003). Behavioral assays have indicated that several of these compounds possess the desirable characteristics described above. For example, RTI-336 (3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-2β-[3-(4’-methylphenyl)isoxazol-5-yl]tropane hydrochloride) displayed a high affinity for DAT (IC50i=4.1 nM) and high selectivity for DAT versus NET and SERT (419- and 1404-fold, respectively; Carroll et al., 2004a), as did a structurally related compound, RTI-177 (3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-2β-(3-phenylisoxazol-5-yl]tropane hydrochloride; IC50=1.3 nM; DAT selectivity 394- and 1890-fold selective versus NET and SERT, respectively, Carroll et al., 2006a,b. Note, however, that Kuhar et al., 1999, reported that RTI-177 displayed only a 2-fold selectivity for DAT vs. NET with respect to the EC50 for uptake inhibition). Rate of entry into the brain, onset of neurochemical and behavioral-stimulant effects in monkeys and onset and duration of locomotor-stimulant effects in rodents were fastest for cocaine and slowest for RTI-177 (Carroll et al., 2004b, 2006a; Kimmel et al., 2001, 2007; Kimmel et al., 2008). Consistent with these pharmacological characteristics, RTI-336 and RTI-177 fully substituted for cocaine in rodent drug discrimination studies by both intraperitoneal and oral routes (Carroll et al., 2004a, 2006a) and by the intramuscular route in monkeys (Kimmel et al., 2008). Moreover, both RTI-336 and RTI-177 can reduce cocaine self-administration in rats and monkeys (Carroll et al., 2006a; Haile et al., 2005; Howell et al., 2007; Lindsey et al., 2004).

In theory, a primary limitation of this approach is that the agonist medication itself may have abuse liability due to the similarity in mechanism of action to an abused drug. Indeed, preclinical data have indicated that RTI-177 is self-administered by monkeys under a second-order schedule of drug injection with response rates similar to those maintained by cocaine (Lindsey et al., 2004; Kimmel et al., 2007). In that study, RTI-336 maintained responding at lower rates, the authors concluded that the data indicated “a trend towards reliable self-administration.” Moreover, RTI-336 was self-administered under a second-order schedule in rhesus monkeys (Howell et al., 2007).

In contrast to the majority of previous studies which assessed reinforcing effects, the aim of the present study was to compare the reinforcing strength of cocaine, RTI-336 and RTI-177 using a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule. Reinforcing strength is a particularly useful concept when translating self-administration data to the clinical situation since drug abusers exist in an environment containing multiple reinforcers of varying strength. Preclinical studies have shown that measures of reinforcing effects (e.g., response rates maintained by ratio- or interval-based schedules of reinforcement) do not provide identical information as measures of reinforcing strength (Arnold and Roberts, 1997). In monkeys, for example, cocaine and the DA uptake inhibitor PTT (2β-propanoyl-3β-(4-tolyl)-tropane) were both self-administered under simple fixed-ratio and fixed-interval reinforcement schedules (Birmingham et al., 1998; Lile et al., 2000; Nader et al., 1997); however, when studied under a PR schedule of reinforcement, fewer injections of PTT were received compared to cocaine (Lile et al., 2002). In the only previous study of these drugs to use a PR schedule, cocaine was a stronger reinforcer than RTI-336 and RTI-177 in three rhesus monkeys (Kimmel et al., 2008). In fact, in 2 of 3 monkeys RTI-177 resulted in the same or more injections than RTI-336; an effect that would not have been predicted by each drug’s onset and duration of action (see Kimmel et al., 2007, 2008). In that PR study, several parameters differed from those used in other studies of reinforcing strength in monkeys and rodents (e.g., Lile et al., 2002, Richardson and Roberts, 1996) including the progression of ratio values, and the maximum number of reinforcers available and the session duration, which were limited. Because variations in these and other parameters can affect results of self-administration studies using PR schedules (cf. Katz, 1990; Martelle et al., 2008; Rowlett et al., 1996), the present studies examined whether previous results generalized to a PR schedule in which the end of the session is determined by the subject, i.e., when a drug injection has not been received for two hours. The longer limited hold used in this study (2 hrs) allows for a more accurate assessment of the reinforcing strength of drugs with slower onsets of action and longer durations of action. Based on earlier work with PTT (Lile et al., 2002), another drug with slower onset and longer duration of action compared to cocaine, we hypothesized that RTI-336 and RTI-177 would be weaker reinforcers than cocaine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

Four adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) with extensive histories of cocaine self-administration and exposure to various monoamine transporter inhibitors (e.g. Lile et al., 2003) served as subjects. Monkeys were weighed monthly and fed enough food daily (Purina Monkey Chow, fresh fruit, peanuts and vegetables) to maintain body weights at approximately 95% of free-feeding levels. Monkeys were individually housed in sound-attenuating chambers (0.91 × 0.91 × 0.91 m; Plas Labs, Lansing, MI). The front wall of each cubicle was constructed of Plexiglas to allow the monkey visual access to the laboratory. Each cubicle was equipped with two response levers (BRS/LVE, Beltsville, MD); only the right lever was used in the present studies. Four stimulus lights, alternating white and red, were located in a horizontal row above each lever. Each animal was fitted with a stainless-steel restraint harness and spring arm (Restorations Unlimited, Chicago, IL) that attached to the rear of the cubicle. A peristaltic infusion pump (Cole-Parmer Co., Chicago, IL) was located on the top of the chamber for delivering injections at a rate of approximately 1.5 ml/10 sec.

2.2. Catheter implantation

Each monkey was prepared with a chronic indwelling venous catheter and subcutaneous vascular access port (Access Technologies, Skokie, IL) under sterile surgical conditions. Anesthesia was induced with ketamine (15 mg/kg) and butorphanol (0.05 mg/kg) and maintained with ketamine supplements. A catheter was inserted into a major vein (femoral, internal or external jugular, brachial) to the level of the vena cava. The distal end of the catheter was passed subcutaneously to a point slightly off the midline of the back, where an incision was made. The end of the catheter was attached to the vascular access port which was placed in a pocket formed by blunt dissection. Following the surgery, the monkey was returned to its chamber. Tubing was connected to the infusion pump, threaded through the spring arm and attached to the port via a 20-gauge Huber Point Needle (Access Technologies). Antibiotics (25 mg/kg Kefzol; Cefazolin sodium, Marsam Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cherry Hill, NJ) were administered 1 hr prior to surgery. To prolong patency, each port and catheter was filled with a solution of heparinized saline (100 U/ml) between experimental sessions.

2.3. Self-administration procedure

Monkeys had been trained previously to self-administer (−) cocaine under a PR schedule in a session that began at approximately 3:00 pm. Before each session, the pump was operated for approximately 30 sec to fill the catheter with the drug solution available for that session. Under the PR schedule, white lights were illuminated above the right lever and 50 responses resulted in a 10-sec injection, extinguishing of white lights and illumination of red lights for 10 sec. A 10-min timeout (TO) period, during which no lights were illuminated and responding had no scheduled consequences, followed each injection. The response requirement for subsequent injections was determined by the exponential equation used by Richardson and Roberts (1996): ratio = [5 × e(R × 0.2)] − 5, where e is the mathematical constant and R is equal to the reinforcer number. For the present studies, the first response requirement (50 responses) corresponds to the 12th value given by this equation and is followed by 62, 77, 95,117, 144, 177, 218, 267, 328, 402, 492, 602, 737, 901, 1102, 1347, etc. Sessions ended when 2 hours elapsed without an injection. Initially, monkeys’ responding was maintained by injections of 0.03 mg/kg cocaine until responding was stable (mean ± 3 injections for 3 consecutive sessions with no trend). Next, a dose-effect curve was determined in each monkey by substituting saline and a range of doses of cocaine (0.003–0.56 mg/kg per injection) for the maintenance dose in a quasi-random order. Finally, dose effect curves for RTI-113 and RTI-177 were constructed for each monkey by replacing the maintenance dose with a dose of one test compound in a quasi-random order until responding stabilized. Doses were available for at least 5 consecutive sessions and until responding was deemed stable.

2.4. Data Analysis

The dependent variable of primary interest was the number of drug injections earned under the PR schedule. For each animal, data were averaged across the last three days of availability of each dose. If criteria for stability of responding were not reached within approximately 8 sessions, the average of the last 5 sessions was used. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used for each drug to determine whether it functioned as a reinforcer, and post-hoc Dunnett’s tests, comparing each dose to saline, determined which doses served as reinforcers. Interpolation of the linear portion of the dose-effect function for individual monkeys was used to determine an ED50 value, i.e., the dose of drug calculated to produce 50% of the maximum response. In addition, maximum reinforcing strength, defined as the peak number of reinforcers earned regardless of dose, was compared across drugs using Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. In all cases, differences were considered statistically significant at the 95% level of confidence (p<0.05). Data are presented as mean (± SD) for individual monkeys.

2.5. Drugs

(−)-Cocaine was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD, and was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline. RTI-336 (3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-2β-[3-(4’-methylphenyl)isoxazol-5-yl]tropane hydrochloride) and RTI-177 (3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-2β-(3-phenylisoxazol-5-yl]tropane hydrochloride) were obtained from Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle, NC) and were also dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline. Drug doses were determined as salts.

3. Results

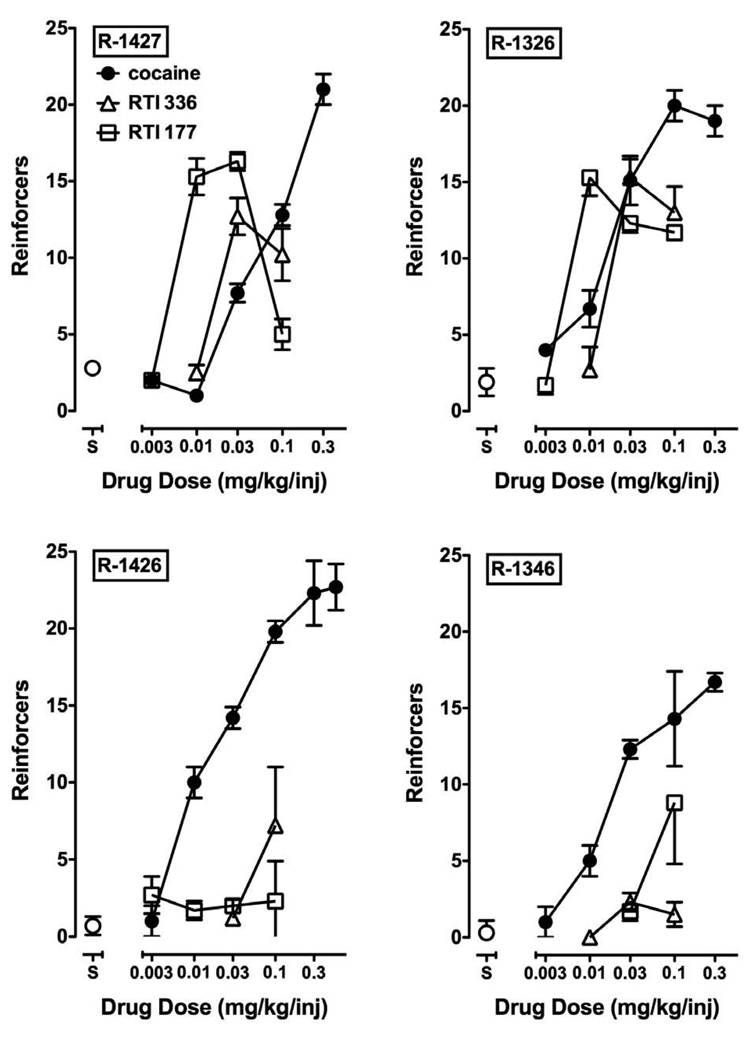

For all monkeys, substitution of saline for the cocaine maintenance dose resulted in a low number of reinforcers (1.4 ± 0.6 injections) within approximately five sessions. When different doses of cocaine (0.003–0.3 mg/kg) were substituted for the maintenance dose, the number of cocaine injections received under the PR schedule increased significantly as a function of dose in all monkeys (Fig. 1). Analysis of grouped data indicated a main effect of cocaine dose (F5,15=43.1, p<0.0001); injections received during availability of doses above 0.01 mg/kg per injection were significantly different from the number of saline injections received. There was also a main effect of RTI 336 dose on injections received (F3,8=5.06, p<0.05); post-hoc analysis indicated that self-administration of 0.03 and 0.01 mg/kg RTI-336 was significantly different from saline self-administration. Analysis of averaged data for RTI-177 indicated an effect of RTI-177 that approached significance (p=0.076). Visual inspection of individual subject data indicated that multiple doses of RTI 336 and RTI 177 functioned as reinforcers in two subjects (R-1427 and R-1326). In addition, the highest tested dose of RTI-336 maintained responding significantly greater than saline in R-1426 and the highest dose of RTI-177 functioned as a reinforcer in R-1346.

Figure 1.

Self-administration of cocaine, RTI-336 and RTI-177 under a progressive-ratio reinforcement schedule in four rhesus monkeys. Ordinate, number of reinforcers earned; abscissa, available dose. Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

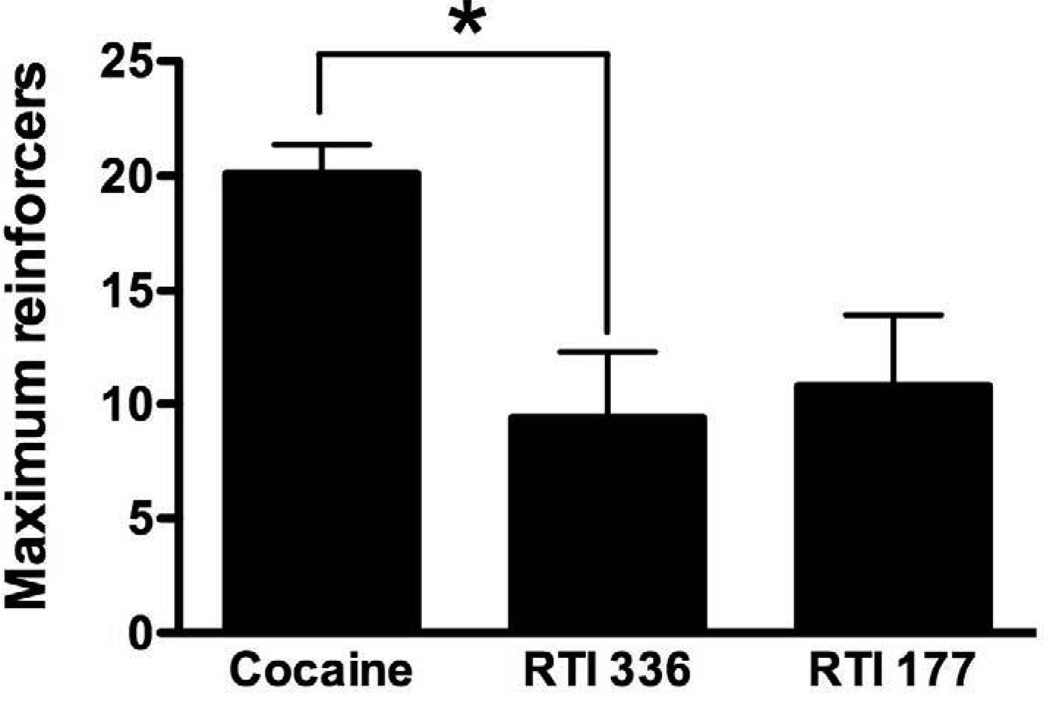

The rank order of potency of cocaine, RTI-336 and RTI-177 differed across monkeys and, on average, no significant differences in potency were observed (Table 1). The peak number of reinforcers earned was lower for both RTI-336 and RTI-177 than for cocaine in all monkeys (Fig. 1). Analysis of grouped data indicated that the maximum reinforcing strength of RTI-336 was significantly lower than that of cocaine (Fig. 2), whereas the difference between the maximum reinforcing strength of cocaine and RTI-177 approached significance (p=0.083). Higher doses of RTI-336 and RTI-177 (0.17 and 0.3 mg/kg) were examined in some monkeys. In all cases, testing of these doses was discontinued within five days due to difficulty with solubility and heightened locomotor activity, which frequently resulted in the Huber needle becoming disconnected from the access port.

Table 1.

ED50 values (mg/kg) for self-administration.

| Subject | cocaine | RTI 336 | RTI 177 |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-1427 | 0.054 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| R-1326 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.005 |

| R-1426 | 0.014 | 0.049 | n.d. |

| R-1346 | 0.020 | n.d. | 0.047 |

| Mean | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.019 |

| S.E.M. | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.017 |

Figure 2.

Maximum number of reinforcers earned during availability of cocaine, RTI-336 and RTI-177. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n=4. Asterisk indicates p<0.05.

4. Discussion

The present studies used a PR schedule of reinforcement to compare the reinforcing strength of cocaine and two 3-phenyltropane analogs, RTI-336 and RTI-177, in rhesus monkeys. Using group data, cocaine and RTI-336, but not RTI-177, functioned as reinforcer. When individual-subject data were used, RTI-336 and RTI-177 were reinforcers in three of four monkeys, while cocaine had reinforcing effects in all animals. The DAT inhibitors were, on average, equipotent with cocaine. As it relates to reinforcing strength, the maximum number of injections earned (i.e., reinforcing strength) was greater for cocaine compared to both RTI-336 and RTI-177 in all subjects. These results complement previous comparisons of self-administration of these drugs in monkeys (Howell et al., 2007; Kimmel et al., 2007, 2008), and support the hypothesis that DAT inhibitors with a slower onset of pharmacological and neurochemical effects are weaker reinforcers than cocaine.

Much preclinical research has been directed toward developing 3-phenyl-tropane analogs as substitute agonist medications for cocaine dependence; the behavioral and neurochemical profile for RTI-336 has been deemed most promising (Carroll et al., 2006). Some of the criteria described as being relevant for an effective cocaine pharmacotherapy include long duration of action and minimal abuse potential (cf. Carroll et al., 2006). Several studies have characterized the reinforcing effects of RTI-336 and the longer-acting analog RTI-177 (see Introduction), but these were all examined using short experimental sessions (2 hrs), which could lead to disproportionately low rates of responding (e.g., Lile et al., 2000). The primary purpose of the present study was to examine the reinforcing strength of RTI-336 and RTI-177 under conditions in which end of the session was determined by the animal. To accomplish this, a self-administration session did not terminate until 2 hours had passed without an injection. This duration of was sufficient to ensure that the limited hold expired in every session. A further rationale for the comparison with the earlier PR study using a shorter session length (Kimmel et al., 2008) was that parametric manipulations may alter interpretation of behavioral effects and yield important information related to the drug’s abuse potential (Katz, 1990). When measures of reinforcing strength (i.e., maximum number of injections) were assessed, the results between the two studies were nearly identical. Using a 2-hr session length, Kimmel et al. (2008) reported maximal injections of approximately 22, 12 and 11 for cocaine, RTI-336 and RTI-177, respectively. When the monkey determined the session length (limited hold of 2 hrs expired), the maximal number of injections were 20, 8 and 9, respectively (see Fig. 2). In contrast, when potency (i.e., the ED50 dose for self-administration) was assessed, Kimmel et al. (2008) found cocaine to be the most potent, followed by RTI-177 and RTI-336 (0.11, 0.59 and 2.7 mg/kg, respectively). We found that using the longer session lengths, the three drugs were approximately equally potent and over a log unit more potent than reported by Kimmel et al. (2008). Such findings suggest that parametric manipulations of the PR schedule as described in this study do not alter measures of reinforcing strength, but do modify the potency of drugs. Determining whether a different conclusion would be supported by manipulating other parameters, such as timeout duration (e.g., Martelle et al., 2008), requires additional study.

The further evaluation of these DAT blockers is of relevance because of the necessity that an agonist treatment agent for cocaine addiction have lower reinforcing strength than cocaine. Data in humans and laboratory animals have suggested that greater behavioral-stimulant and reinforcing effects are associated with drugs that enter the brain, occupy the DAT and increase extracellular DA more rapidly (e.g., Kimmel et al., 2007; Volkow et al., 2000, 2002; Woolverton and Wang, 2004). Although DAT inhibitors with a slow onset of pharmacological action can function as reinforcers under PR and other schedules of reinforcement, they are typically weaker reinforcers than cocaine (Lile et al., 2002, 2003; Stafford et al., 2001; Woolverton et al., 2002). The implications of the present findings for use of DAT blockers as treatment agents is that the abuse liability of RTI-336 or RTI-177 is likely to be lower than that of cocaine. However, despite the fact that onset of neurochemical and behavioral-stimulant effects is more rapid for RTI-336 than for RTI-177 (Carroll et al., 2004a,b; Kimmel et al., 2007), a clear difference in reinforcing strength between these two cocaine analogs was not observed in the present study. This ambiguity is difficult to resolve in light of the marked individual differences in drug effects across the four monkeys in the present study. There were no substantial differences in experimental or pharmacological history across monkeys that could explain these discrepancies. It should be noted, however, that attempts to study higher doses of these compounds were limited by insufficient solubility of the drug and by production of behavioral stimulation that interfered with self-administration. It is likely that reinforcing strength is determined by an interaction between pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors and that further parametric studies using several behavioral endpoints will be required to more fully understand this relationship (Woolverton et al., 2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Susan Nader for assistance in completing these studies. Funding for this study was provided by NIDA grants DA 06634 and DA 05477.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors declare that they have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Arnold JM, Roberts DCS. A critique of fixed and progressive ratio schedules used to examine the neural substrates of drug reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;57:441–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Madras BK, Johnson SE, Spealman RD. Effects of cocaine and related drugs in nonhuman primates III. Self-administration by squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham AM, Nader SH, Grant KA, Davies HM, Nader MA. Further evaluation of the reinforcing effects of the novel cocaine analog 2β-propanoyl-3β-(4-tolyl)-tropane (PTT) in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1998;136:139–147. doi: 10.1007/s002130050549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI. Medicinal Chemistry Division Award address: monoamine transporters and opioid receptors. Targets for addiction therapy. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1775–1794. doi: 10.1021/jm030092d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Fox BS, Kuhar MJ, Howard JL, Pollard GT, Schenk S. Effects of dopamine transporter selective 3-phenyltropane analogs on locomotor activity, drug discrimination, and cocaine self-administration after oral administration. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006a;553:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Howard JL, Howell LL, Fox BS, Kuhar MJ. Development of the dopamine transporter selective RTI-336 as a pharmacotherapy for cocaine abuse. AAPS J. 2006b;8:E196–E203. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Howell LL, Kuhar MJ. Pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine abuse: preclinical aspects. J Med Chem. 1999;42:2721–2736. doi: 10.1021/jm9706729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Pawlush N, Kuhar MJ, Pollard GT, Howard JL. Synthesis, monoamine transporter binding properties, and behavioral pharmacology of a series of 3beta-(substituted phenyl)-2beta-(3'-substituted isoxazol-5-yl)tropanes. J Med Chem. 2004a;47:296–302. doi: 10.1021/jm030453p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Runyon SP, Abraham P, Navarro H, Kuhar MJ, Pollard GT, Howard JL. Monoamine transporter binding, locomotor activity, and drug discrimination properties of 3-(4-substituted-phenyl)tropane-2-carboxylic acid methyl ester isomers. J Med Chem. 2004b;47:6401–6409. doi: 10.1021/jm0401311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Shearer J, Merrill J, Negus SS. Agonist-like, replacement pharmacotherapy for stimulant abuse and dependence. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1439–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile CN, Zhang XY, Carroll FI, Kosten TA. Cocaine self-administration and locomotor activity are altered in Lewis and F344 inbred rats by RTI-336, a 3-phenyltropane analog that binds to the dopamine transporter. Brain Res. 2005;1055:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Carroll FI, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Kimmel HL. Effects of combined dopamine and serotonin transporter inhibitors on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:757–765. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.108324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Wilcox KM. The dopamine transporter and cocaine medication development: drug self-administration in nonhuman primates. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL. Models of relative reinforcing efficacy of drugs and their predictive utility. Behav Pharmacol. 1990;1:283–301. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199000140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel HL, Carroll FI, Kuhar MJ. Locomotor stimulant effects of novel phenyltropanes in the mouse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;65:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel HL, Negus SS, Wilcox KM, Ewing SB, Stehouwer J, Goodman MM, Votaw JR, Mello NK, Carroll FI, Howell LL. Relationship between rate of drug uptake in brain and behavioral pharmacology of monoamine transporter inhibitors in rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel HL, O'Connor JA, Carroll FI, Howell LL. Faster onset and dopamine transporter selectivity predict stimulant and reinforcing effects of cocaine analogs in squirrel monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Morgan D, Birmingham AM, Wang Z, Woolverton WL, Davies HM, Nader MA. The reinforcing efficacy of the dopamine reuptake inhibitor 2β-propanoyl-3β-(4-tolyl)-tropane (PTT) as measured by a progressive-ratio schedule and a choice procedure in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:640–648. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Morgan D, Freedland CS, Sinnott RS, Davies HM, Nader MA. Self-administration of two long-acting monoamine transport blockers in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2000;152:414–421. doi: 10.1007/s002130000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Nader MA. The abuse liability and therapeutic potential of drugs evaluated for cocaine addiction as predicted by animal models. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2003;1:21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Wang Z, Woolverton WL, France JE, Gregg TC, Davies HM, Nader MA. The reinforcing efficacy of psychostimulants in rhesus monkeys: the role of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:356–366. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey KP, Wilcox KM, Votaw JR, Goodman MM, Plisson C, Carroll FI, Rice KC, Howell LL. Effects of dopamine transporter inhibitors on cocaine self-administration in rhesus monkeys: relationship to transporter occupancy determined by positron emission tomography neuroimaging. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:959–969. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelle JM, Czoty PW, Nader MA. Effect of time-out duration on the reinforcing strength of cocaine assessed under a progressive-ratio schedule in rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:743–746. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283123c6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Negus SS. Preclinical evaluation of pharmacotherapies for treatment of cocaine and opioid abuse using drug self-administration procedures. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:375–424. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00274-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader MA, Grant KA, Davies HM, Mach RH, Childers SR. The reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of the novel cocaine analog 2β-propanoyl-3β-(4-tolyl)-tropane in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:541–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Behavioral effects of cocaine and dopaminergic strategies for preclinical medication development. Psychopharmacology. 2002;163:265–282. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods. 1996;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Blough BE, Woolverton WL, Anderson KG, Negus SS, Mello NK, Roth BL, Baumann MH. Development of a rationally designed, low abuse potential, biogenic amine releaser that suppresses cocaine self-administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:1361–1369. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Glowa JR. A review of the effects of dopaminergic agents on humans, animals, and drug-seeking behavior, and its implications for medication development: Focus on GBR 12909. Molecular Neurobiol. 1995;10:1–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02740680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett JK, Massey BW, Kleven MS, Woolverton WL. Parametric analysis of cocaine self-administration under a progressive-ratio schedule in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1996;125:361–370. doi: 10.1007/BF02246019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford D, LeSage MG, Rice KC, Glowa JR. A comparison of cocaine, GBR 12909, and phentermine self-administration by rhesus monkeys on a progressive-ratio schedule. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathis M, Scheffel U, Lever SZ, Boja JW, Carroll FI, Kuhar MJ. Rate of binding of various inhibitors at the dopamine transporter in vivo. Psychopharmacology. 1995;119:376–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02245852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci FJ, Acri J, Elkashef A. Medication development for addictive disorders: the state of the science. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1432–1440. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. Imaging studies on the role of dopamine in cocaine reinforcement and addiction in humans. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:337–345. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fischman MW, Foltin R, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Franceschi M, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Wong C, Ding YS, Hitzemann R, Pappas N. Effects of route of administration on cocaine induced dopamine transporter blockade in the human brain. Life Sci. 2000;67:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00731-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Gatley SJ. Role of dopamine in the therapeutic and reinforcing effects of methylphenidate in humans: results from imaging studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12:557–566. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Wang Z. Relationship between injection duration, transporter occupancy and reinforcing strength of cocaine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;486:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Ranaldi R, Wang Z, Ordway GA, Paul IA, Petukhov P, Kozikowski A. Reinforcing strength of a novel dopamine transporter ligand: pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:211–217. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.037812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]