Abstract

Aims

The current study examined developmental changes in substance use behaviors (SUBS) based on sexual orientation. The analyses also attempted to address a number of methodological limitations in the extant longitudinal literature. (i.e., distinct operationalizations of sexual orientation, timing of sexual orientation assessment with respect to reports of SUBs, non-linear growth).

Participants

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study of incoming first-time college students at a large, public university.

Design

After a paper-and-pencil assessment just prior to matriculation (N = 3720), participants completed a web-based survey every fall and spring for four years (n = 2854).

Findings

Latent growth models revealed that sexual minorities demonstrated significant heterogeneity with regard to substance use trajectories. Initial levels and trajectories of the frequency of substance use for sexual minority individuals were distinct, generally, from their exclusively heterosexual peers. Methodologically, the timing of the assessment of sexual orientation influenced the results, and modeling nonlinear components indicated that sexual minorities are at risk for exponential increases in their frequency of certain SUBs over time (i.e., drunkenness; cannabis use).

Conclusions

Sexual minority and majority individuals exhibited differences in SUBs during emerging adulthood, especially when using self-identification to define sexual orientation. Individuals who endorsed a sexual minority self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood, as opposed to four years later, evidenced exponential increases in rates of drunkenness and cannabis use, providing support that the timing of assessment is important and that some trajectories of sexual minority SUBs are non-linear during this developmental period.

Sexual minority individuals are at elevated risk for engagement in substance use behaviors [SUBs; 1-3]. Moreover, disparities between sexual minority and majority women may be more pronounced [2,4-16] than their male counterparts. Demonstrating this liability for the acquisition of SUBs, a recent meta-analysis of 18 studies by Marshal et al. [2] found that the odds of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (GLB) adolescents, under age 18, using substances (i.e., cigarette, alcohol, illicit drugs) were 190% higher than for heterosexual youth. Several explanations exist for this vulnerability to substance use among sexual minorities [e.g., coping with sexual prejudice; 1; see also 9,17-21 for alternative explanations]. An in-depth examination of the developmental pattern of SUBs among sexual minority individuals may be helpful in understanding their distinct etiologic pathways.

The majority of past research has been limited to cross-sectional data [e.g., 13,14,16,18,22-25] and only six studies [4,9,11,26-28] have examined patterns of substance use among non-clinical samples of sexual minority individuals over time and compared those to the patterns of use among samples of sexual majority individuals. Overall, the findings of these longitudinal studies provide further evidence that sexual minority adolescents and young adults may be at increased risk for SUBs, which are generally variable over time.

There are two major issues, however, that are not adequately resolved in previous longitudinal research on sexual orientation and SUBs. First, theoretical [e.g., 29] and empirical [2,30] distinctions between sexual minority self-identifications, sexual attractions, and sexual behaviors (i.e., operationalizations of sexual orientation) have not been adequately considered in the extant literature. Second, studies have assessed sexual orientation at a single time point or infer sexual minority status based on participants' longitudinal endorsement of at least one operationalization of sexual orientation in their past. Illustrating these concerns, studies have assessed self-reported same-sex sexual attractions and behaviors once at the beginning of the study period [29], sexual minority self-identification, sexual attractions and behaviors once at the final wave of the study period [11], combined assessments of sexual minority self-identification and same-sex sexual attractions from one [4] or two different time points [26,27], or combined a one-time assessment of sexual orientation based on self-identification with at least one report of a same-sex partner in one's sexual history [9].

To the extent that reports of sexual orientation show evidence of temporal instability [e.g., 30-32 for female samples], interpretations of single-occasion reports of sexual orientation indicators and related changes in SUBs over time are problematic in that they may provide biased estimates of correlations with time-varying behaviors of interest. Thus, existing research has failed to critically examine temporal relations between distinct operationalizations of sexual orientation and changes in SUBs.

Providing the basis for this report, a recent study by Marshal et al. [11] examined substance use trajectories among sexual minority adolescents from the Add Health Study who were in grades 7 to 12 [e.g., 30,33] at baseline. Marshal et al. [11] revealed that individuals who endorsed a sexual minority self-identification (i.e., any non-exclusively heterosexual sexual identity), as opposed to those who endorsed an “exclusively heterosexual” self-identification, reported a higher frequency of binge drinking, alcohol use, and cigarette use at the first wave of data collection and increased more sharply in their frequency of drunkenness, alcohol use, cigarette use and cannabis use over time. Notably, the findings were found to be somewhat distinct for each operationalization of sexual orientation.

Though Marshal et al.'s [11] results provide compelling evidence that sexual minority youth are at greater risk for engagement in SUBs, their findings are limited in several ways. One issue, as noted by Marshal et al., is that the assessment of sexual orientation occurred only at the last measurement occasion. Thus, sexual orientation at the end of the developmental period was used to predict initial differences in substance use trajectories at the first wave of data collection and subsequent linear growth over three waves (i.e., postdictively), precluding an examination of whether sexual orientation assessed in adolescence provided distinct prospective predictions regarding trajectories of SUBs.

Additionally, although it is known that there are nonlinear changes in the frequency of substance use in adolescent and young adults samples [e.g,. 26,34], it was not possible for Marshal et al. to examine non-linear changes (e.g., quadratic growth) in substance use across time because only three measurement occasions were assessed. We anticipated possible differences in the magnitude and pattern of the relations between our study and Marshal et al. because, whereas Marshal et al. examined only linear changes in SUBs beginning in early adolescence and extending into emerging adulthood, our sample was exclusively comprised of individuals in emerging adulthood, a period in which substances are likely to become readily available and in which the frequency and quantity of substance use is known fluctuate in a non-linear fashion [e.g., 26,34].

The Current Study

The present study sought to replicate and extend the findings of Marshal et al. [11] in a prospective cohort of individuals matriculating in a university as first-time students to determine if differences in substance use trajectories between sexual majority and sexual minority individuals occurred during emerging adulthood, a developmental period characterized by more normative use. Specifically, based on prior research [e.g., 1-3], we anticipated that sexual minority individuals would report heightened levels and distinct trajectories of SUBs compared to their sexual majority peers [e.g., 11]. Because the transition to emerging adulthood is accompanied by a large, normative increase in drinking behavior [35], we also considered that differences with regard alcohol use may be less pronounced during this developmental period [5,6].

Additionally, as outlined above, we attempted to address a number of methodological concerns in the extant literature that we thought could materially affect previous findings. Specifically, we examined relations between all three facets of sexual orientation and compared them on associations with SUBs during emerging adulthood. Next, we examined whether differential effects emerged when substance use trajectories were predicted from sexual orientation indicators that were assessed at the conclusion of the developmental period under investigation (i.e., eighth semester in college) as opposed to the onset (i.e., second semester in college). Finally, given that misspecification of statistical models may greatly influence the interpretation and implications of results [36], we examined quadratic effects in substance use trajectories to more adequately capture changes in patterns of SUBs [35].

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a prospective study of substance use and health behaviors. For the precollege assessment, 3,720 (88%) of 4,226 incoming first-time college students at the University of Missouri—Columbia completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire in the summer orientation preceding college matriculation. This precollege sample was followed up and administered a Web-based survey every fall (October/November) and spring (March/April) of the subsequent 4 years. Thus, a one unit change in Wave corresponds to an approximate 6-month time interval. Written parental permission/consent was obtained for all participants under age 18, and assent/consent was obtained from each participant.

The data from the current report are limited to those collected beginning in the second semester of college (n = 2854) because that is when sexual orientation was initially assessed. Participants were 61% female, 90% Caucasian, and 18.76 (SD = .46) years of age on average at the first assessment. Fifty-five percent of the baseline sample participated in at least one follow-up assessment throughout the first four years of emerging adulthood (i.e., college) and 45% completed all assessments. Recent findings have provided evidence that this sample was minimally influenced by retention biases [35; see supplementary analyses].

Measures

Sexual Orientation Indicators

As in Marshal et al. [11], sexual orientation was operationalized in three ways: (a) self-identification (i.e., self-labeling of sexual identity); (b) sexual attraction, (i.e., degree of opposite- vs. same-sex sexual attractions); and (c) sexual behavior, (i.e., degree of opposite- vs. same-sex sexual activity).

The current results pertain to operationalizations of sexual orientation assessed during the second and eighth semester of college. To assess self-identification, participants were asked: “How would you describe your sexual orientation?” Response options were: 1=exclusively homosexual, 2=primarily homosexual, 3=equally homosexual and heterosexual, 4=primarily heterosexual, 5=exclusively heterosexual. Similarly, sexual attractions and sexual behaviors were assessed with single, 7-point items asking participants, respectively, “To which group are you sexually attracted?” and “With which group do you engage in sexual behavior?” (1=opposite-sex only; 2=opposite-sex mostly; 3=opposite-sex somewhat; 4=both sexes equally; 5=same-sex somewhat; 6=same-sex mostly; 7=same-sex only). A dichotomous variable denoted two groups, based on participants' sexual orientation self-identification (0 = exclusively heterosexual; 1 = primarily heterosexual/equally homosexual and heterosexual/primarily homosexual/exclusively heterosexual). Similarly, two dichotomous variables denoted groups based on participants' sexual attractions and behaviors, respectively (0 = opposite-sex only; 1 = opposite-sex mostly/opposite-sex somewhat/both sexes equally/same-sex somewhat/same-sex mostly/same-sex only).

Substance Use Frequency

Drunkenness was assessed with a single item, “Over the past 30 days, on how many days have you gotten drunk on alcohol?” Binge drinking was assessed with a single item, “Over the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink five or more drinks in a row?” A single item at each assessment measured the frequency with which participants used a number of substances (i.e., alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis) in the previous three months on a 8-point scale (0=Never/Not in the past 3 months; 7=More than 40 times)

Covariates

Participants reported their age during the initial intake into the study (in years) and this variable was centered baseline. Additionally, participants indicated their sex (0 = female, 1 = male), ethnicity (0 = Non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic), and race (0 = White/European American, 1 = Black/African American, American Indian/Native American, Asian/Pacific Islander, Other).

Analytic Procedure

To examine substance use trajectories based on sexual orientation, Latent Growth Modeling (LGM) was utilized. LGMs were estimated using Mplus Version 5.1 [37]. These models examine the development of individuals on one or more outcome variables over time by using random effects conceptualized as continuous latent growth factors [38]. This approach has a number of advantages, including the use of multiple assessment periods and the models being tolerant of missing data. The substance use outcomes intercept and slope factors represent the modeling of the respective outcome variables (i.e., frequency of drunkenness, binge drinking, alcohol and drug use). The intercept factor represents initial levels (roughly age 18) of the respective constructs of substance use involvement. The slope factors represent change in the respective construct over the entire study period (see online supplemental material). Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors [39] was employed for the LGMs. To allow for analysis of data containing missing values, all LGMs were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood.

Results

Initially, changes in sexual orientation from Wave 2 to Wave 8 were examined. A non-trivial number of individuals (n = 251) were found to change their sexual orientation self-identification, providing some evidence for the fluid nature of sexual orientation and suggesting that prospective and postdiction models may differ. Observed means, at each time point, regarding the frequency of drunkenness, binge drinking, alcohol use, cigarette use, and cannabis use are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics regarding SUBs for the Overall Sample and Split by Sex and Sexual Orientation Self-identification at Baseline.

| Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | Wave 5 | Wave 6 | Wave 7 | Wave 8 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Drunkenness | 1.28 | (1.34) | 1.24 | (1.31) | 1.19 | (1.32) | 1.29 | (1.26) | 1.29 | (1.30) | 1.33 | (1.29) | 1.34 | (1.31) |

| Binge drinking | 1.26 | (1.39) | 1.28 | (1.41) | 1.25 | (1.41) | 1.31 | (1.36) | 1.32 | (1.42) | 1.36 | (1.38) | 1.33 | (1.40) |

| Freq. of alcohol use | 2.58 | (1.87) | 2.75 | (1.86) | 2.67 | (1.86) | 2.96 | (1.78) | 3.1 | (1.73) | 3.30 | (1.67) | 3.27 | (1.65) |

| Freq. of cigarette use | 1.19 | (2.06) | 1.19 | (2.05) | 1.13 | (2.01) | 1.17 | (2.02) | 1.06 | (1.97) | 1.13 | (2.02) | 1.03 | (1.95) |

| Freq. of cannabis use | 0.67 | (1.46) | 0.62 | (1.42) | 0.59 | (1.38) | 0.61 | (1.45) | 0.58 | (1.39) | 0.60 | (1.41) | 0.55 | (1.39) |

Note. Freq. = frequency, M = Mean, SD = Standard deviation. Drunkenness was assessed with a single item, “Over the past 30 days, on how many days have you gotten drunk on alcohol?” Binge drinking was assessed with a single item, “Over the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink five or more drinks in a row?” Participants were asked on a 8-point scale (0=Never/Not in the past 3 months; 7=More than 40 times) how often in the past three months they had used a number of substances (i.e., alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis). Majority = exclusively heterosexual at Wave 2; Minority = primarily heterosexual, bisexual, primarily homosexual, or exclusively homosexual at Wave 2.

Unconditional Growth Model

The unconditional growth models revealed that intercepts for each of the outcomes were significantly different from zero, indicating that participants generally reported at least some substance use at baseline. Linear slopes were also significant for frequency of drunkenness, binge drinking, and alcohol use, suggesting significant mean-level (i.e., normative) increases in these behaviors during college. By contrast, frequency of cigarette and cannabis use did not exhibit significant mean-level linear changes during college. These models also indicated significant variation around both intercepts and linear slopes, suggesting individual differences in trajectories across time.

Do Findings from an Adolescent Sample Generalize to a Sample in Emerging Adulthood?

Conditional, postdiction models examined whether unique patterns of SUBs were evidenced across different operationalizations of sexual orientation endorsed at the end of the study period. Consistent with Marshal et al. [11], the intercept was initialized at the first wave of the study period (i.e., Wave 2) and linear growth trajectories were predicted using sexual orientation indicators reported during the last wave of the study period (i.e., Wave 8). As shown in Table 2, compared to their exclusively heterosexual peers (n=1605), individuals who endorsed any degree of a sexual minority self-identification during the last wave of the study period (n=288) reported higher initial frequencies of alcohol, β = .15, p < .05, cigarette, β = .26, p < .001, and cannabis use, β = .36, p < .001, but not drunkenness or binge drinking, at the onset of emerging adulthood. Subgroups of sexual minority participants (i.e., exclusively/primarily homosexual (n=93), bisexual (n=9), primarily heterosexual (n=186)) were created and their substance use trajectories were compared to those of exclusively heterosexual participants (n=1605; see Table 2, Model 2). These findings generally replicated Model 1 with regard to higher initial rates of cigarette and cannabis use among self-identified sexual minority subgroups.

Table 2. Latent Growth Models Testing the Postdictive (Wave 8) and Predictive (Wave 2) Association between Operationalizations of Sexual Orientation and Linear Substance Use Trajectories, Controlling for Covariates (n = 2,854).

| Frequency | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drunkenness | Binge Drinking | Alcohol Use | Cigarette Use | Cannabis Use | ||||||

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |

| Sexual minority self-identification | ||||||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||||

| Wave 8 | .09 | -.04a | .08 | -.10a | .15* | -.03a | .26*** | .17a | .36*** | .08a |

| Wave 2 | .12 | -.16 | .16* | -.25* | .15* | -.10 | .35*** | .05 | .44*** | -.07 |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||

| Wave 8 PS | .05 | -.01 | .03 | -.04 | .07 | -.02 | .16*** | .08 | .22*** | .02 |

| Wave 2 PS | .09* | -.09 | .11** | -.13* | .10** | .03 | .21*** | .04 | .29*** | -.06 |

| Wave 8 Bi | .05 | -.01 | .05 | -.07 | .11 | -.06 | .23** | .16 | .31*** | .09 |

| Wave 2 Bi | .09 | -.15 | .13* | -.22* | .11 | -.08 | .31*** | .06 | .15*** | -.04 |

| Wave 8 P/EG | .07 | -.05 | .08 | -.10 | .13** | -.10 | .17** | .12 | .21*** | .09 |

| Wave 2 P/EG | .06 | -.11 | .09* | -.18* | .09* | -.10 | .21*** | .02 | .22*** | .00 |

| Same-sex sexual attraction | ||||||||||

| Model 3 | ||||||||||

| Wave 8 | .05 | .00 | .04 | -.06 | .12* | .07 | .45*** | .26** | .51*** | .09 |

| Wave 2 | .09 | -.18 | .06 | -.19 | .12 | -.06 | .36*** | .05 | .59*** | -.14 |

| Same-sex sexual behavior | ||||||||||

| Model 4 | ||||||||||

| Wave 8 | .00 | .16 | -.09 | .25 | .09 | .03 | .34** | .31 | .24 | .23 |

| Wave 2 | .17 | -.25 | .12 | -.22 | .23* | -.25 | .54*** | .15 | .15*** | -.02 |

Note. Standardized, adjusted coefficients are presented. Drunkenness: “Over the past 30 days, on how many days have you gotten drunk on alcohol?”. Binge drinking: “Over the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink five or more drinks in a row?” Frequency of alcohol, cigarettes, and cannabis use (0=Never/Not in the past 3 months; 7=More than 40 times). PS = Primarily heterosexual, Bi = Bisexual, P/EG = Primarily/Exclusively homosexual. Model 1: (0=Exclusively heterosexual [ES]; 1=PS, Bi, P/EG). Model 2: MS (0=ES; 1=PS); Bi (0=ES; 1=Bi); P/EG (0=ES, 1=P/EG). Model 3: Same-sex sexual attraction (0=Opposite-sex only; 2=Opposite-sex mostly/Opposite-sex somewhat/Both sexes equally/Same-sex somewhat/Same-sex mostly/Same-sex only). Model 4: Same-sex sexual behavior (same anchors as attraction).

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

In addition, substance use trajectories of individuals who reported some degree of attraction to same-sex individuals (n=315) and those who reported engaging in some degree of same-sex sexual behaviors (n=110) were compared to persons who reported completely opposite-sex attractions (n=1582) and behaviors (n=1649), respectively (see Table 2, Models 3 and 4). Consistent with results for self-identification, individuals who endorsed any same-sex sexual attractions during the last wave of the study period reported higher initial frequencies of alcohol, β = .12, p < .05, cigarette, β = .45, p < .001, and cannabis use, β = .51, p < .001, at the onset of emerging adulthood, as well as greater linear increases in their cigarette use over time, β = .26, p < .01, compared to their peers who endorsed only opposite-sex attractions. When comparing individuals who endorsed any degree of same-sex sexual behavior during the last wave of the study period to their peers who reported having only opposite-sex sexual partners, only higher initial rates of cigarette use, β = .34, p < .01, were found.

Does Timing of Sexual Orientation Assessment Influence Analytic Conclusions?

Prediction models parallel to those discussed previously were run that utilized sexual orientation assessed at the onset of emerging adulthood. As shown in Table 2, results indicated that persons endorsing any level of sexual minority self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood reported higher initial levels of binge drinking, β = .16, p < .05, as well as a higher frequencies of alcohol, β = .15, p < .05, cigarette, β = .35, p < .001, and cannabis use, β = .44, p < .001. In contrast to the postdiction models, prediction models indicated that participants who self-identified as sexual minorities during at the onset of emerging adulthood (n=301) experienced decreases (as opposed to normative increases) in rates of binge drinking over time, β = -.25, p < .05, compared to their exclusively heterosexual peers (n=2003).

For persons endorsing any degree of same-sex sexual attraction (n=234) at the onset of emerging adulthood, results indicated higher risk for cigarette, β = .36, p < .001, and cannabis use, β = .59, p < .001, compared to their peers who were only attracted to opposite-sex sexual partners. Critically, no differences were found among any alcohol involvement variables. Finally, among those who endorsed any degree of same-sex sexual behavior at the onset of emerging adulthood, compared to their counterparts who only engaged in opposite-sex sexual behaviors, higher initial rates of the frequency of their alcohol, β = .23, p < .05, cigarette, β = .54, p < .001, and cannabis use, β = .15, p < .001, were found. Notably, an examination of model fit indices (i.e., AIC, BIC) indicated that postdiction models provided a better fit to the data.

Does Sexual Minority Status Influence Non-linear Changes in Substance Use?

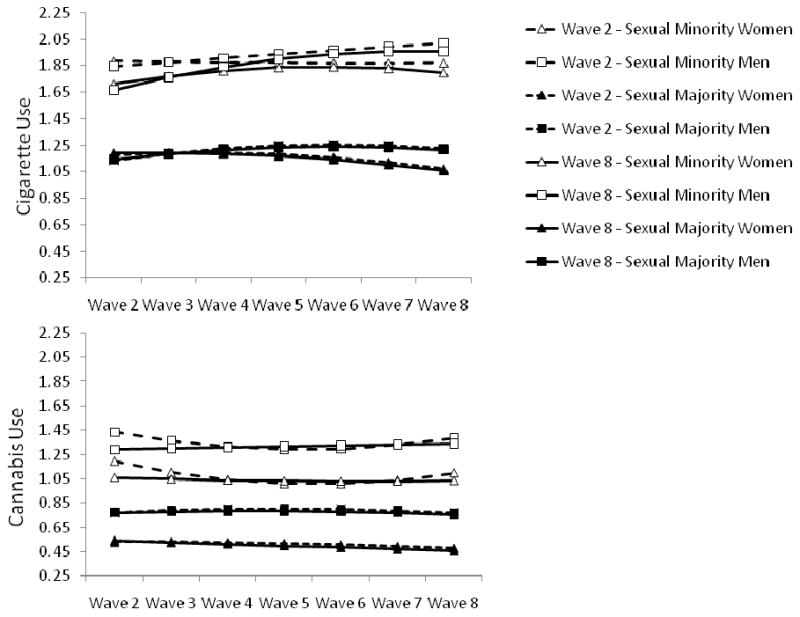

Corrected chi-square difference tests suggested that quadratic models were a significant improvement over linear-slope-only models for all outcomes. Significant variation around intercepts, linear changes, and acceleration rates for all primary outcome variables were found in all models, suggesting heterogeneity with regard to individual trajectories. When discussing the outcomes of quadratic models, the term “accelerate” is used to denote the curvilinear increases/decreases in the rate of a given behavior over the course of time. Due to space limitations, the postdictive, quadratic models are not reviewed in detail. Nevertheless, the results of the parallel postdiction and prediction quadratic models are presented in Table 3. In addition, Figures 1 and 2 provide visual depictions of substance use trajectories for both postdictive and predictive models with regard to sexual orientation self-identification.

Table 3. Latent Growth Models Testing the Postdictive (Wave 8) and Predictive (Wave 2) Association between Operationalizations of Sexual Orientation and Non-linear Substance Use Trajectories, Controlling for Covariates (n = 2,854).

| Frequency | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drunkenness | Binge Drinking | Alcohol Use | Cigarette Use | Cannabis Use | |||||||||||

| Inter | Linear | Quad | Inter | Linear | Quad | Inter | Linear | Quad | Inter | Linear | Quad | Inter | Linear | Quad | |

| Sexual minority self-identification | |||||||||||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Wave 8 | .18* | -.53*** | .59***a | .11 | -.22 | .20a | .18** | -.18 | .15a | .26** | .11 | -.05a | .38*** | -.02 | .05a |

| Wave 2 | .17* | -.47*** | .48** | .20** | -.32* | .25 | .14* | -.05 | .00 | .36*** | -.05 | .10 | .49*** | -.29* | .30* |

| Model 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Wave 8 PS | .10* | -.31*** | .35*** | .05 | -.11 | .10 | .09* | -.09 | .08 | .15** | .08 | -.05 | .24*** | -.04 | .04 |

| Wave 2 PS | .11* | -.24* | .24* | .12** | -.16* | .12 | .10** | -.01 | -.01 | .21*** | -.01 | .04 | .32*** | -.19* | .19* |

| Wave 8 Bi | .14 | -.50*** | .57*** | .08 | -.22* | .21 | .13 | -.14 | .12 | .23** | .09 | -.03 | .33*** | -.02 | .05 |

| Wave 2 Bi | .13* | -.39** | .38** | .15* | -.24* | .18 | .11 | -.03 | -.01 | .32*** | -.06 | .11 | .46*** | -.24* | .23 |

| Wave 8 P/EG | .13* | -.32** | .34** | .10* | -.15 | .12 | .16*** | -.15 | .11 | .17** | .06 | -.01 | .22*** | .02 | .01 |

| Wave 2 P/EG | .11* | -.36*** | .37** | .12* | -.26* | .22* | .09 | -.06 | .01 | .22*** | -.04 | .06 | .25*** | -.16* | .19* |

| Same-sex sexual attraction | |||||||||||||||

| Model 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Wave 8 | .14 | -.44** | .51*** | .08 | -.20 | .20 | .16* | -.14 | .18 | .42*** | .28 | -.18 | .53*** | -.04 | .08 |

| Wave 2 | .14 | -.47** | .45* | .09 | -.27* | .23 | .12 | -.02 | .00 | .39*** | -.11 | .16 | .63*** | -.26 | .24 |

| Same-sex sexual behavior | |||||||||||||||

| Model 4 | |||||||||||||||

| Wave 8 | .11 | -.50* | .69** | -.04 | -.13 | .29 | .16 | -.33 | .36 | .35** | .11 | .03 | .32* | -.23 | .35 |

| Wave 2 | .21* | -.48* | .42 | .12 | -.16 | .07 | .18 | .13 | -.28 | .59*** | -.20 | .32 | .73*** | -.26 | .26 |

Note. Standardized, adjusted coefficients are presented. Drunkenness: “Over the past 30 days, on how many days have you gotten drunk on alcohol?”. Binge drinking: “Over the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink five or more drinks in a row?” Frequency of alcohol, cigarettes, and cannabis use (0=Never/Not in the past 3 months; 7=More than 40 times). Inter = Intercept, Quad = Quadratic; PS = Primarily heterosexual, Bi = Bisexual, P/EG = Primarily/Exclusively homosexual. Model 1: (0=Exclusively heterosexual [ES]; 1=PS, Bi, P/EG). Model 2: MS (0=ES; 1=PS); Bi (0=ES; 1=Bi); P/EG (0=ES, 1=P/EG). Model 3: Same-sex sexual attraction (0=Opposite-sex only; 2=Opposite-sex mostly/Opposite-sex somewhat/Both sexes equally/Same-sex somewhat/Same-sex mostly/Same-sex only). Model 4: Same-sex sexual behavior (same anchors as attraction).

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Figure 1.

Estimated (from LGMs) mean-level changes in alcohol involvement over time from postdictive and predictive models as moderated by sexual orientation self-identification and sex. Sexual Majority = exclusively heterosexual; Sexual Minority = primarily heterosexual/bisexual/primarily homosexual/exclusively homosexual.

Figure 2.

Estimated (from LGMs) mean-level changes in cigarette and cannabis use over time from postdictive and predictive models as moderated by sexual orientation self-identification and sex. Sexual Majority = exclusively heterosexual; Sexual Minority = primarily heterosexual/bisexual/primarily homosexual/exclusively homosexual.

Prediction models revealed that, compared to their exclusively heterosexual peers, persons who reported any degree of a sexual minority self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood endorsed higher initial levels of drunkenness, β = .17, p < .05, and binge drinking, β = .20, p < .01, as well as a greater frequency of alcohol, β = .14, p < .05, cigarette, β = .36, p < .001, and cannabis use, β = .49, p < .001. For alcohol involvement outcomes (i.e., drunkenness, binge drinking), significant intercept differences were consistently found across various endorsements of minority self-identifications (e.g., primarily heterosexual; bisexual) but not necessarily reports of same-sex sexual attractions or behaviors (see Table 3). Critically, there was also evidence for an acceleration in the frequency drunkenness among individuals who endorsed a sexual minority self-identification, compared to those who reported an exclusively heterosexual self-identification (see Figure 1). This curvilinear growth in predictive models was also replicated for individuals who endorsed same-sex sexual attractions but not for those who endorsed same-sex sexual behaviors.

As seen in Figure 2, higher initial rates of cigarette and cannabis use were found for individuals who endorsed a sexual minority self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood as well as for those who indicated some degree of same-sex sexual attraction or behavior, compared to their sexual majority counterparts. Additionally, individuals who endorsed a minority, as opposed to a majority, self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood evidenced curvilinear growth in the frequency of their cannabis use over time, β = .30, p < .05 (see Table 3, Model 1; see also Figure 2).

Discussion

Building on previous studies [e.g., 4-7,9,11,23,26,28], the current findings suggest significant developmental differences between sexual minority and majority individuals on a range of SUBs in emerging adulthood. Additionally, the current study extends the literature in important ways. First, it provides suggestive evidence that the initiation and course of SUBs may differ for individuals who endorse a sexual minority sexual orientation at the onset of emerging adulthood versus four years later. Second, it suggests that self-identification as a sexual minority, per se, may contribute to heightened risk for engagement in certain SUBs. Third, it effectively argues that non-linear changes in the SUBs of sexual minorities need to be considered to adequately characterize the unfolding of their substance use patterns. Evidence for gender-moderated effects, however, was sparse in the current sample (see supplementary analyses), suggesting that the processes described above are similar for women and men.

Operationalization of the Assessment for Sexual Orientation Matters

The current findings are consistent with studies suggesting that distinct operationalizations of sexual orientation may be differentially associated with SUBs [e.g., 2,7,8,11,16,40]. Specifically, patterns of heightened alcohol involvement were more often found for individuals endorsing a sexual minority self-identification and less often replicated for individuals who reported same-sex sexual attractions [see also 11; c.f., 7,16,40] or behaviors [see also 11, c.f., 5,7,8,16,40]. These results suggest that self-identification as a sexual minority may, in and of itself, impose heightened risk for the acquisition and maintenance of alcohol-related behaviors during emerging adulthood.

The findings examining cigarette and cannabis use among sexual minority individuals suggest that sexual minority self-identification [7,11], as well as same-sex sexual attractions or behaviors [5,7,11,16,40], predicted greater initial and sustained use of both substances, compared to their respective sexual majority counterparts. Individuals with a sexual minority self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood were also found to accelerate in their cannabis use over time, suggesting that self-identification as a sexual minority may, as with alcohol related behaviors, impose heightened risk for the accelerated use of illicit substances during emerging adulthood.

Timing of the Assessment for Sexual Orientation Matters

Although similarities between the postdictive and predictive findings may be more apparent with regard to drunkenness and cigarette use, there were noticeable differences with regard to the frequency of binge drinking and cannabis use. For example, whereas those who endorsed a sexual minority self-identification at the onset of emerging adulthood first declined and then exponentially increased (i.e., accelerated) in their cannabis use over time, individuals who endorsed a sexual minority self-identification at the last assessment did not evidence acceleration in cannabis use and, instead, simply maintained elevated rates of cannabis use throughout the first four years of emerging adulthood. That distinct patterns of SUBs were found between postdicitive and predictive models suggests that the timing of the assessment of individuals' sexual orientation is important [see also, 41,42].

The current findings also supported Diamond's [31,32] work with samples of female sexual minorities, by providing additional evidence that sexual identity development is a fluid process such that individuals may not endorse consistent sexual identities, attractions, or behaviors over time. As evidence, a significant proportion of individuals in the current sample changed their sexual orientation over the study (6-8% of the sample). Speculatively, individuals identifying as sexual minorities at the onset of emerging adulthood may be more engaged in a tentative exploration of sexuality or may not have fully accepted a non-heterosexual identity [e.g.,43-49], whereas those who identify as sexual minorities four years later may have achieved a relatively stable sexual identity and may have had more time to integrate their sexual identity into their self-concept [48]. Thus, individuals who identify as sexual minorities at an earlier age may be otherwise engaged in a myriad of exploratory behaviors and grappling with identity-related stress. As such, their SUBs may follow a trajectory distinct from those who identify as sexual minorities four years later and who may have had time to gather appropriate competencies necessary for managing their sexual identity and SUBs [42].

Evidence for Non-linear Changes in Substance Use

Misspecification of statistical models may greatly influence the interpretation of results [36]. Indeed, there were a number of disparate findings when non-linear substance use trajectories were estimated and compared to linear trajectories. Thus, it is imperative that researchers consider and test higher-order or non-linear time effects, when appropriate, to adequately capture changes in these behaviors over time.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are limitations that must be considered when interpreting the study's findings. First, the data are based on a sample of college students, a majority of whom are White/Caucasian. It is difficult to know whether these results are likely to generalize to other populations (e.g., individuals not attending college; ethnic minorities). A recent review of the literature [50], however, found that SUBs among lesbians and gay men of color appear more similar to those of White lesbians and gay men than to their racial/ethnic heterosexual counterparts, suggesting that the current results may generalize to other demographic strata. Nevertheless, future studies are needed to confirm this. Second, only two assessments of sexual orientation were considered. Given that the current study implied individual differences with regard to the fluidity of sexual orientation, it may be fruitful for future researchers to examine how changes in sexual orientation over time correspond to changes in trajectories of substance use over time.

Although previous researchers have highlighted the role that minority stress plays in provoking the use of drugs and alcohol as means to cope with sexual prejudice and its associated stressors [e.g., 13,14,24,25,51,52], others have posited that sexual minorities may use alcohol and drugs due to more permissive peer norms [9,25] or as a way to reinforce a valued group identity through shared social activities [e.g., 13-15,53]. That the current findings revealed some SUBs accelerated in emerging adulthood (i.e., drunkenness) suggests that environmental/social factors (i.e., attaining legal drinking age, socializing in public bars) may exacerbate the use of alcohol and certain types of drugs among sexual minorities in this stage of life. Though the current study did not address what explanatory variables may account for the discrepancies in the patterns of SUBs, future research should examine which explanations may account for changes in these behaviors during emerging adulthood. Once the risks for disparities are identified, they may be examined in the context of an individual's sexual identity development process to better understand their contributions to sustained and detrimental patterns of use (e.g., experimentation, peer influence). By considering the findings from the extant literature, we may be able to better manage the diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorders and the associated comorbid psychopathology among sexual minority individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants T32 AA13526, R37 AA07231 and KO5 AA017242 to Kenneth J. Sher. Also, we thank the staff of the Alcohol, Health, and Behavior and IMPACTS projects for their data collection and management.

The authors would like to think Lynne Cooper for her comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. In addition, we would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None Declared

References

- 1.Bux DA., Jr The epidemiology of problem drinking in gay men and lesbians: A critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 1996;16:277–298. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paul J, Stall R, Bloomfield K. Gay and alcoholic: epidemiologic and clinical issues. Alcohol Health Res W. 1991;5:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, Austin B. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.11.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenberg M, Wechsler H. Substance use behaviors among college students with same-sex and opposite-sex experience: results from a national study. Addict Behv. 2003;28:899–913. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCabe SE, Boyd C, Hughes TL. Sexual identity and substance use among undergraduate students. Sub Abuse. 2003;24:77–91. doi: 10.1080/08897070309511536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick W, Boyd CJ. Assessment of difference in dimensions of sexual orientation: implications for substance use research in a college-aged population. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:620–629. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Midanik LT, Drabble L, Trocki K, Sell RL. Sexual orientation and alcohol use: identity versus behavior measures. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3:25–35. doi: 10.1300/j463v03n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatzenbuehler ML, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Trajectories and determinants of alcohol use among LGB young adults and their heterosexual peers: results from a prospective study. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:81–90. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziyadeh NJ, Prokop LA, Fisher LB, Rosario M, Field AE, Camargo CA, Austin B. Sexual orientation, gender, and alcohol use in a cohort study of U.S. adolescent girls and boys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction. 2009;104:974–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochran SD, Ackerman D, Mays VM, Ross MW. Prevalence of non-medical drug use and dependency among homosexually active men and women in the U.S. population. Addiction. 2004;99:989–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predictors of substance use over time among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: an examination of three hypotheses. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, Pollack LM, Bein E, Crosby GM, et al. Alcohol use, drug use, and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men's Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96:1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright ER, Perry BL. Sexual identity distress, social support, and the health of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. J Homosex. 2006;51:81–110. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, West BT, Boyd CJ. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulenberg J, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during the transition to young adulthood. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;14:57–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual respondents: results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orenstein A. Substance use among gay and lesbian adolescents. J Homosexuality. 2001;41:1–15. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKirnan DJ, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Sex, drugs, and escape: A psychological model of HIV-risk sexual behaviors. AIDS Care. 1996;8:655–669. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berglas S, Jones EE. Drug choice as a self-handcapping strategy in response to noncontingient success. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1978;36:405–417. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.36.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amadio DB. Internalized heterosexism, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems among lesbians and gay men. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridner SL, Frost K, LaJoie AS. Health information and risk behaviors among gay, lesbian, and bisexual college students. J Am Acad Nurse Prac. 2006;18:374–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Butch/femme differences in substance use and abuse among young lesbian and bisexual women: examination and potential explanations. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1002–1015. doi: 10.1080/10826080801914402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong CF, Kipke MD, Weiss G. Risk factors for alcohol use, frequent use, and binge drinking among young men who have sex with men. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debord KA, Wood PK, Sher KJ, Good GE. The relevance of sexual orientation to substance abuse and psychological distress among college students. J College Student Development. 1998;39:157–168. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rostosky SS, Danner F, Riggle EDB. Is religiosity a protective factor against substance use in young adulthood? only if you're straight! J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rostosky SS, Danner F, Riggle EDB. Religiosity and alcohol use in sexual minority and heterosexual youth and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37:552–563. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sell RL. Defining and measuring sexual orientation: a review. Arch Sex Behav. 1997;26:643–658. doi: 10.1023/a:1024528427013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond LM. Was it a phase? young women's relinquishment of lesbian/bisexual identities over a 5-year period. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:352–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diamond LM. A new view of lesbian subtypes: stable versus fluid identity trajectories over an 8-year period. Psychol Women Q. 2005;29:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanton CA, Papandonatos GD, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Niaura R. Consistency of self-reported smoking over a six-year interval from adolescence to young adulthood. Addiction. 2007;102:1831–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perlstadt H, Hembroff LA, Zonia SC. Changes in status, attitude and behavior toward alcohol and drugs on a university campus. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance. 1991;14:44–62. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addict Behav. 2007;32:812–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bliese PD, Ployhart RE. Growth modeling using random coefficient models: model building, testing, and illustrations. Organizational Research Methods. 2002;5:362–387. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén;; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: a structural equation perspective. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eye A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent variables analysis: applications for developmental research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N. Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: implications for substance use and abuse. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:198–202. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sex. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: John Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parks CA, Hughes TL. Age differences in lesbian identity development and drinking. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:361–380. doi: 10.1080/10826080601142097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glover JA, Galliher RV, Lamere TG. Identity development and exploration among sexual minority adolescents: examination of a multidimensional model. J Homosexuality. 2009;56:77–101. doi: 10.1080/00918360802551555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horowitz JL, Newcomb MD. A multidimensional approach to homosexual identity. J Homosexuality. 2001;42:1–19. doi: 10.1300/j082v42n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. J Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coleman E. The developmental stages of the coming out process. J Homosexuality. 1981;7:31–43. doi: 10.1300/j082v07n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diamond LM. Development of sexual orientation among adolescent and young adult women. Dev Psych. 1998;34:1085–1095. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dube EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual minority male youths. Dev Psych. 1999;35:1389–1399. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McDonald GJ. Individual differences in the coming out process for gay men: Implications for theoretical models. J Homosexuality. 1982;8:47–60. doi: 10.1300/J082v08n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hughes TL, Eliason M. Substance use and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. J Prim Prev. 2002;22:263–298. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber G. Using to numb the pain: substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2008;30:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trocki KF, Drabble L, Midanik L. Use of heavier drinking contexts among heterosexuals, homosexuals, and bisexuals: results from a national household probability survey. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2005;66:105–110. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.