Abstract

Objective To determine the relation between overweight and obesity in mothers and preterm birth and low birth weight in singleton pregnancies in developed and developing countries.

Design Systematic review and meta-analyses.

Data sources Medline and Embase from their inceptions, and reference lists of identified articles.

Study selection Studies including a reference group of women with normal body mass index that assessed the effect of overweight and obesity on two primary outcomes: preterm birth (before 37 weeks) and low birth weight (<2500 g).

Data extraction Two assessors independently reviewed titles, abstracts, and full articles, extracted data using a piloted data collection form, and assessed quality.

Data synthesis 84 studies (64 cohort and 20 case-control) were included, totalling 1 095 834 women. Although the overall risk of preterm birth was similar in overweight and obese women and women of normal weight, the risk of induced preterm birth was increased in overweight and obese women (relative risk 1.30, 95% confidence interval 1.23 to 1.37). Although overall the risk of having an infant of low birth weight was decreased in overweight and obese women (0.84, 0.75 to 0.95), the decrease was greater in developing countries than in developed countries (0.58, 0.47 to 0.71 v 0.90, 0.79 to 1.01). After accounting for publication bias, the apparent protective effect of overweight and obesity on low birth weight disappeared with the addition of imputed “missing” studies (0.95, 0.85 to 1.07), whereas the risk of preterm birth appeared significantly higher in overweight and obese women (1.24, 1.13 to 1.37).

Conclusions Overweight and obese women have increased risks of preterm birth and induced preterm birth and, after accounting for publication bias, appeared to have increased risks of preterm birth overall. The beneficial effects of maternal overweight and obesity on low birth weight were greater in developing countries and disappeared after accounting for publication bias.

Introduction

The continuum of overweight and obesity is now the most common complication of pregnancy in many developed and some developing countries. In the United Kingdom, 33% of pregnant women are overweight or obese.1 In the United States, 12%2 to 38%3 of pregnant women are overweight and 11%4 to 40%3 are obese. In India, 8% of pregnant women are obese and 26% are overweight5 and in China, 16% are overweight or obese.6

Preterm birth is the leading cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity and childhood morbidity7 followed by low birth weight.8 Whether maternal overweight and obesity is associated with increased,9 decreased,10 or neutral risks11 of preterm birth has been debated in the literature, with the uncertainty reflected in the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Committee opinion on obesity in pregnancy.12 Even low birth weight, which is typically thought to be reduced in infants of overweight and obese women,3 is sometimes associated with neutral risks.5 To accurately risk stratify a pregnancy at the first antenatal visit, as is standard, it is important to know the effect of overweight and obesity in mothers on preterm birth and low birth weight. We therefore undertook a systematic, comprehensive, and unbiased accumulation and summary of the available evidence from all study designs with a reference group of normal weight women to determine the direction and magnitude of the association of maternal overweight and obesity with preterm birth and low birth weight in singleton pregnancies in developed and developing countries.

Methods

We carried out a systematic review and meta-analyses in accordance with the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology consensus statement.13

With the help of a librarian we searched Medline (1950 to 2 January 2009) and Embase (1980 to 2 January 2009), using individual comprehensive search strategies. This study was part of a constellation of systematic reviews examining maternal anthropometry and preterm birth and low birth weight (see search strategy in web extra appendix 1). Additional eligible studies were sought by reviewing the reference lists of identified articles.

Study eligibility criteria

For the constellation of systematic reviews examining maternal anthropometry, we included randomised trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies if one or more of the following maternal anthropometry variables was assessed as an exposure variable: body mass index (*=assessed before pregnancy, during pregnancy or postpartum), weight*, gestational weight gain, attained weight, or height*; and one or more of the following outcomes was assessed: preterm birth (<37 weeks, 32-36 weeks, and <32 weeks) and low birth weight (<2500 g), very low birth weight (<1500 g), and extremely low birth weight (<1000 g). Studies were restricted to those in English. For this particular systematic review of maternal overweight and obesity, we included studies with any body mass index definition of overweight and obese or very obese, whether from self report, objective measurement, medical charts, or databases.

We excluded duplicate publications, studies published only as abstracts, those involving fewer than 10 patients, and those that examined outcomes in multiples unless stratification was done for singleton versus twin outcomes.

Outcome measures

Our primary outcomes were preterm birth (before 37 weeks) and low birth weight (<2500 g) in singletons. Where possible we subdivided preterm birth into spontaneous and induced. Secondary outcomes were late preterm birth (32-36 weeks) and moderate preterm birth (before 32 weeks), and very low birth weight (<1500 g) and extremely low birth weight (<1000 g).

We also reported the following outcomes for studies that met the above inclusion criteria and mentioned intrauterine growth restriction (defined as birth weight <10% for gestational age), birth weight (grams), and gestational age at birth (weeks).

Study and data collection processes

Two assessors (two of ZH, SDM, and SM) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of all identified citations. The full text article was retrieved if either reviewer considered the citation potentially relevant. Two reviewers (two of ZH, SDM and SM) independently evaluated each full text article. Disagreements were settled by discussion and consensus, with a third person as an adjudicator.

From full text articles and using a piloted data collection form, two reviewers independently extracted data on country of origin, years of study, study design, characteristics of participants, outcomes, and information on bias. We included information available from the publications. Inconsistencies were checked and resolved through the consensus process.

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager, version 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration), for statistical analyses. For cohort studies we used relative risks to meta-analyse crude and separately, adjusted, dichotomous data, whereas for case-control studies we used odds ratios to pool crude and separately, matched or adjusted dichotomous data. Continuous data were analysed using a mean difference. Weighting of the studies in the meta-analyses was calculated on the basis of the inverse variance of the study. The random effects model was chosen because it accounts for both random variability and the variability in effects among the studies as we expected a degree of clinical and statistical heterogeneity among the studies, which were all observational. Crude, matched, and adjusted data were initially pooled separately and then matched or adjusted data were pooled together. Where required and when the incidence of the outcome was rare, to be able to pool data, adjusted relative risks were calculated from adjusted odds ratios.14 As is typical in meta-analyses, we did not adjust for multiple analyses. We focused on the combined results of overweight, obese, and very obese; however, where possible we also separately reported results for each individually in the summary tables. Clinical heterogeneity was evaluated. We calculated the I2 value to measure heterogeneity. An I2 value represents the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than due to chance.15 Values of 25%, 50%, and 75% have been regarded as representing low, moderate, and high heterogeneity.15

Sensitivity analyses were planned a priori using a few chosen groups to examine the effects of level of material wellbeing (developed v developing countries16), study quality (see web extra appendix 2), youth (adolescence v adulthood), and race. Three post hoc sensitivity analyses were carried out (see web extra appendix 3) to examine the effects of self reported compared with measured body mass index; body mass index assessed before pregnancy, during pregnancy, or post partum; and using exact cut-offs for body mass index with a reference body mass index of 20-25 versus those with cut-offs close to this.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (two of ZH, SDM, and SM) independently assessed study quality using a predefined evaluation of six types of biases: selection, exposure, outcome, confounding, analytical, and attrition (see web extra appendix 2). This bias assessment tool has been described in other reviews undertaken by our group on determinants of preterm birth and low birth weight.17

To deal with publication bias we showed results without imputation as well as with imputation: the latter using Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method for estimating and adjusting for the number and outcomes of missing studies in a meta-analysis18 19—that is, to adjust for any observed publication bias. A priori we decided to carry out the trim and fill analyses for outcomes with at least 10 studies as there were concerns of reliability for outcomes with fewer studies. We used the generic inverse variance method to calculate study specific weights. These analyses were done using the R statistical and programming software, version 2.9.0. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

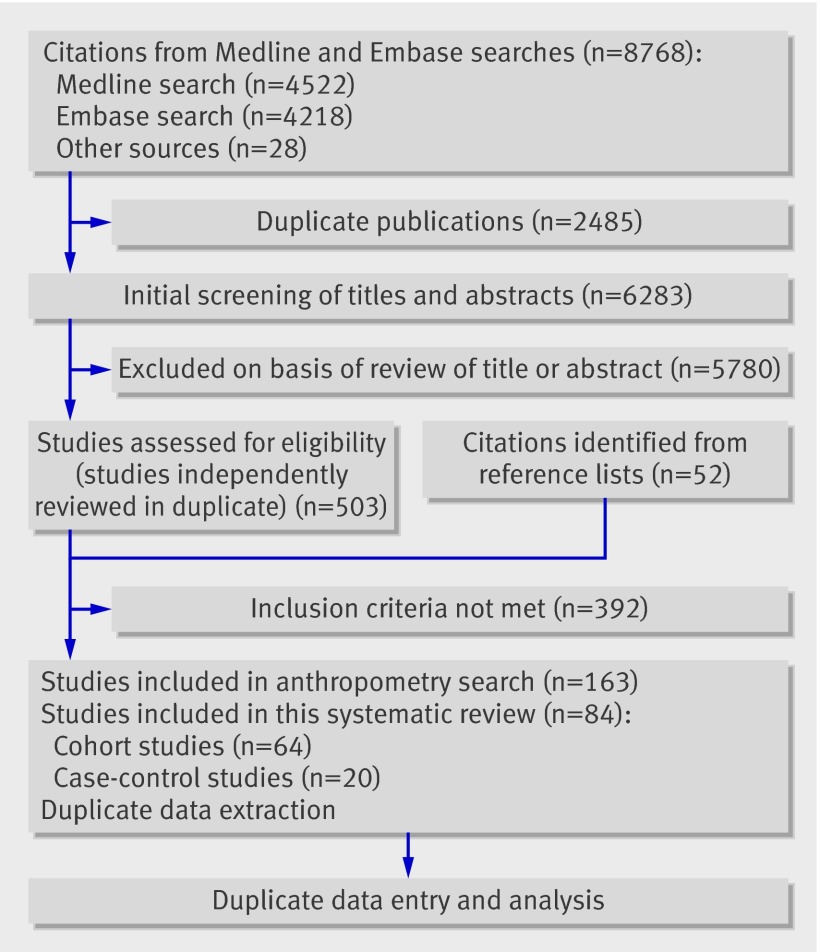

Overall, 6283 non-duplicated titles and abstracts were identified (fig 1). After the screening process, 503 citations were selected to undergo review of the full text article, and a further 52 articles were identified from reference lists, yielding a total of 555 full text articles for review. The most common reasons for exclusion were failure to report outcomes of interest and study design.

Fig 1 Study selection process

Eighty four studies were included: 64 cohort studies2 3 4 5 6 9 10 11 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 (58 with pooled data) and 20 case-control studies76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 (19 with pooled data), totalling at least (some studies did not report the number of patients) 1 095 834 women (fig 1, tables 1 and 2). The studies originated predominantly from developed countries, although developing countries were also represented. The majority of the studies assessed body mass index by self report. Most studies did not report the timing of body mass index assessment, although when reported it was most commonly at the first antenatal visit.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort studies included in systematic review and meta-analyses of preterm birth and low birth weight in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Study (period) | Population | Setting | Body mass index (BMI) | No of women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self report or measured | When recorded | Definition of exposure (high BMI) | Exposed | Not exposed | ||||

| Abenhaim* 200725 (1987-97) | All women who delivered live or stillborn infants ≥500 g | University of California, San Diego Medical Center, USA | Self report | In labour | 30-39.9 | NR | NR | |

| Adams 19959 (1987-90) | Black and white enlisted service women who delivered live or stillborn singletons at or after 20 weeks’ gestation | Four army medical centres, USA | NR | NR | ≥26.0 | 67 | 1419 | |

| Ancel 199954 (1994-7) | Exposed: all consecutive single preterm births at 22-36 weeks. Unexposed: randomly selected 1 of every 10 consecutive term (>37 weeks) single births. Sample included live and stillborn infants | 15 European countries | Measured | NR | >29.8 (v 18.3-29.8) | 728 | 11 328 | |

| Baeten 200159 (1992-6) | Nulliparous women who delivered live singletons | Washington State, USA | Self report | NR | ≥25 | 27 353 | 50 378 | |

| Barros 199651 (18 months) | Consecutive women who delivered live singleton at level 2 facility or for last four months of study at level 3 facility (teaching hospital) | Hospital de Famalicào and Hospital de S Joao Porto, Porto, Portugal | Self report | ≤48 hours of birth | ≥25 | 951 | 2158 | |

| Berkowitz 199826 (1986-94) | Women who delivered singletons; one pregnancy was randomly selected for women who had more than one eligible pregnancy | Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City, USA | NR | NR | >26.0 | 754 | 1668 | |

| Bhattacharya 200727 (1976-2005) | All primigravid women who delivered singletons after 24 weeks’ gestation in Aberdeen city and district | Aberdeen maternity neonatal databank, UK | Measured | Before pregnancy | ≥25 | 7323 | 14 076 | |

| Bianco 199860 (1988-95) | Morbidly obese women and non-obese women aged 20-34 with singletons | Mount Sinai Medical Centre, Toronto, Canada | Self report | NR | >35 (v 19-27) | 613 | 11 313 | |

| Bondevik 200128 (1994-6) | Outpatient women at first antenatal visit | Patan Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal | NR | NR | >24 | 313 | 661 | |

| Callaway 200629 (1998-2002) | Women with singletons booked for antenatal care | Mater Mother’s Hospital, south Brisbane, Australia | Measured | <12 weeks’ gestation | >25 | 4809 | 6443 | |

| Clausen 200630 (1995-7) | Women of Norwegian ancestry with an appointment for ultrasound screening | Aker Hospital, covered 14 of 23 districts from Oslo, Norway | NR | 17-9 weeks’ gestation | >25 | 690 | 2183 | |

| Cogswell 199550 (1990-1) | Women on low income at high nutritional risk enrolled in supplemental food programme with single, live, term infants; one infant selected from women who delivered more than one baby in 1990-1 | Eight states in USA | Self report | NR | >26.0 | 19 732 | 33 809 | |

| Cnattingius* 199861 (1992-3) | Women born in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland, or Iceland with information on prepregnancy BMI, who delivered singletons registered in Swedish medical birth register | Sweden | Self report | First antenatal visit | ≥30 | NR | NR | |

| De 200748 (1996-2004) | Women who initiated prenatal care <20 weeks’ gestation, were aged ≥18, could speak and read English, planned to carry pregnancy to term, and were to deliver at one of two hospitals | Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, or Tacoma General Hospital, Tacoma, Washington, USA | Self report | NR | ≥25 | 634 | 1450 | |

| Dietz 200624 (1996-2001) | Women with singleton births from pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system | 21 states in USA | Self report | NR | >26 | 33 582 | 59 088 | |

| Driul 200831 (2006) | Women with singletons and complete baseline maternal clinical information and pertinent outcome data | University of Udine, Italy | NR | NR | ≥25 | 153 | 533 | |

| Dubois 200632 (1998-2002) | Random sample of children born in public health districts during 1998 | Quebec, Canada | Self report | NR | ≥25 | 568 | 1253 | |

| Frederick† 200846 (1996-2004) | English speaking women aged ≥18, who planned to deliver at one of two hospitals and were at ≤20 weeks’ gestation at enrolment | Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, or Tacoma General Hospital, Tacoma, Washington, USA | Self report | Before pregnancy | >26 | 489 | 1629 | |

| Gardosi 200033 (1988-95) | Consecutive women with singleton live births | Hospital, Birmingham, UK | Measured | First antenatal visit | >29.4 (v 20.1-29.4) | 2372 | 15 964 | |

| Gilboa 200834 (1981-9) | White or black women with liveborn infants at 25-40 weeks; exposed: randomly selected, without birth defects or pregestational diabetes | District of Columbia, Northern Virginia, Maryland, USA | Self report | NR | ≥25 | 687 | 2218 | |

| Goldenberg 199810 (1992-4) | Women selected to reflect population by race and parity and identified at ≤24 weeks’ gestation | National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Network, 10 centres in USA | NR | NR | >26 | 1037 | 1251 | |

| Haas 200555 (May 2001 to July 2002) | Women who delivered singletons, participated in Project WISH, and received prenatal care at a practice or clinic associated with the delivery hospitals and planned to deliver at one of these hospitals; were aged ≥18 at recruitment; spoke English, Spanish, or Cantonese; sought prenatal care <16 weeks’ gestation; and could be contacted by telephone | Six delivery hospitals in San Francisco Bay area, California, USA | Self report | First antenatal visit <20 weeks | ≥25 | 702 | 863 | |

| Hauger 200811 (2003-6) | Women with pregnancies ending in live birth or fetal death, at ≥22 weeks’ gestation or birth weight >500 g | 10 public hospitals in Buenos Aires city and province, Argentina | Self report | First antenatal visit | ≥25 | 12 327 | 29 644 | |

| Hendler 200557 (1992-4) | Women with maternal height and prepregnancy weight available | 10 medical centres in USA | NR | NR | >30 (v <30) | 597 | 2313 | |

| Hickey 199735 (1982-6) | All women on low income who registered for prenatal care | Five clinical centres: California, Illinois, Ohio, Tennessee, Alabama, USA | Self report | Before pregnancy | >26.0 | 2775 | 6943 | |

| Hulsey 200536 (1998-9) | Women with live singleton with birth weight ≥500 g | South Carolina, USA | NR | NR | >26 | 27 236 | 45 916 | |

| Jensen 200321 (1992-6) | Women with oral glucose tolerance test who delivered first pregnancy in one of four hospitals | Four hospitals in Copenhagen, Denmark | NR | NR | ≥25 | 1365 | 1094 | |

| Johnson 199258 (1987-9) | All women with singleton live births who delivered at ≥38 weeks and received prenatal care | Shands Hospital, Gainesville, Florida, USA | Self report | First antenatal visit | >26 | 815 | 2621 | |

| Kim 200547 (2001-4) | Women with singleton pregnancy at 20-42 weeks who had had obstetric ultrasound and were admitted to one of the included hospitals | Five institutions in Korea | Self report | NR | ≥25 | 171 | 1112 | |

| Kumari 200122 (1996-8) | Women who attended antenatal clinic, weighing ≥90 kg during first 12 weeks of pregnancy | Al-Mafraq Hospital, Abu-Dhabi, United Arab Emirates | NR | NR | >40 (v 22-28) | 188 | 300 | |

| Lawoyin 199237 (1988) | Randomly selected gravid women at first antenatal clinic visit with singletons | Random yet fair representation of whole city, Ibadan, Nigeria | Measured | NR | ≥25 | 268 | 109 | |

| Leung 20086 (1995-2005) | Ethnically Chinese women with singleton pregnancy who presented at ≤20 weeks’ gestation and gave birth at ≥24 completed weeks | University obstetric unit, Hong Kong, China | NR | NR | ≥25 | 4633 | 22 041 | |

| Lumme 199538 (1985-6) | Women with singleton pregnancies | Northern Finland | NR | NR | ≥25 | 1592 | 6433 | |

| Maddah 200544 (Jun 2002 to May 2003) | Women who attended one of six health centres randomly selected from total 12 centres in city | Six health centres, Rasht, Iran | Self report | NR | >26 | 82 | 414 | |

| Merlino 200639 (1996-2004) | All women delivering live or stillborn infant >20 weeks | One medical centre, university, Cleveland, USA | Measured | NR | >25 | 957 | 1374 | |

| Mobasheri 200749 (2004-5) | Women who regularly attended two urban and rural centres for prenatal care | Gorgan, Iran | Self report | NR | >26 | 108 | 161 | |

| Monaghan 200140 (1992-5) | All pregnant women in two hospitals, with last menstrual period between 25 Dec 1992 and 23 Jul 1994 | Dniprovski region of Kyiv and Dniprodzerzhinsk, Ukraine | Measured | NR | ≥25 | 474 | 1387 | |

| Nohr 200723 (1996-2002) | Women with singletons who accepted invitation and signed consent form for Danish National Birth Cohort | Danish National Birth Cohort, Denmark | Self report | Early pregnancy | ≥25 | 23 695 | 57 923 | |

| Ogbonna 200741 (1998-9) | Women living in urban centres near hospital and delivering at university affiliated hospital | Harare Maternity Hospital, Harare, Zimbabwe | Measured | Post partum, before discharge | >24.6 | 234 | 117 | |

| Ogunyemi 199862 (1990-5) | Consecutive black women on low income who registered for prenatal care in first trimester, who delivered singleton >37 weeks | Western Alabama, USA | Self report | First antenatal visit | >26 | 281 | 223 | |

| Panahandeh 200752 (2002-3) | Women who delivered after 38 weeks who were cared for at one of seven health centres randomly selected from 15 centres | Seven local health centres (rural region), Guilan, Iran | NR | NR | >26 | 223 | 219 | |

| Panaretto* 200645 (2000-3) | All women with singletons presenting to Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Service for antenatal care | Panaretto hospital, tertiary referral centre for north Queensland, Australia | Self report | First antenatal visit | >25 | NR | NR | |

| Rahaman 199056 (NR) | Exposed: 300 consecutive obstetric patients with BMI >30. Unexposed: equivalent number with BMI 20-27 | NR (assumed Trinidad, West Indies) | NR | NR | >30 (v 20-27) | 290 | 299 | |

| Ray 200120 (1993-8) | First pregnancy in all consecutive women with singletons and with pregestational or gestational diabetes | Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada | NR | NR | ≥25 | 275 | 218 | |

| Rode 200564 (1998-2001) | Women in Copenhagen first trimester study, who registered <15 weeks, who had a singleton cephalic delivery >37 weeks | Three hospitals in Copenhagen, Denmark | Self report | NR | >25 | 1742 | 6350 | |

| Rode 200753 (Nov 1996 to Oct 1998) | Women with singleton, term pregnancies aged ≥18, fluent in Danish, without alcohol or drug misuse, and answered questionnaire at 12-18 and 37 weeks | University hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark | Self report | 12-18 wks | >26 | 562 | 1531 | |

| Roman 200742 (2001-5) | Exposed: all obese women (prepregnancy BMI >30) after 22 weeks. Unexposed: normal weight (prepregnancy BMI 18.5-25) | Sud-Reunion Hospital, Reunion Island, France | Self report | First antenatal visit | >30 | 2050 | 2066 | |

| Roman 20083 (1994-2004) | Women who received prenatal care and delivered vaginally or by caesarean section during labour | Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, USA | Measured | At delivery | ≥25 | 5393 | 1556 | |

| Ronnenberg 200343 (NR) | Full time employed textile workers, newly married, nulliparous, aged 20-34, with permission to have a child | AnQing, China | Measured | NR | 19.8-26 | 272 | 146 | |

| Sahu 20075 (2005-6) | Women from all socioeconomic levels with singleton pregnancies | Queen Mary’s Hospital, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India | NR | NR | ≥25 | 129 | 205 | |

| Salihu* 20084 (1989-97) | Women at 20-44 weeks with live births | Missouri, USA | Self report | First visit | >30 (v 18.9-24.5) | NR | NR | |

| Savitz 20052 (Aug 1995 to Feb 2001) | Women who came to participating clinic before 30 weeks’ gestation with singleton pregnancy, had access to telephone, were able to communicate in English, and planned to continue care and deliver at study hospital | University of North Carolina Hospitals, Wake County Human Services, and Wake Area Health Education Centre in central North Carolina, USA | Self report | 24-29 weeks | >26 | 852 | 1102 | |

| Sayers* 199773 (1987-90) | Women with liveborn singletons, who self identified as aboriginal in delivery suite register | Royal Darwin Hospital, Darwin health region, Northern Territory, Australia | Measured | Post partum before discharge | >25.5 | NR | NR | |

| Scholl 198974 (NR) | 2789 white, black, and Hispanic adolescents ( <18 years at entry of care) who delivered live singletons and were registered with Camden County Adolescent Family Life Project | Five hospitals and clinics in Camden County, West Jersey Health Systems, NJ, USA | Self report | First antenatal visit | >24.1 | 415 | 1164 | |

| Sebire 200163 (1989-97) | Women with singleton pregnancies with data in St Mary’s maternity information system database | National Health Service Hospital, Northwest Thames Region, UK | Measured | First antenatal visit | >25 | 110 290 | 176 923 | |

| Siega-Riz† 199665 (1983-7) | Women at public health clinics undergoing first pregnancy | Public health clinics, West Los Angeles, USA | Self report | NR | >26 | 1227 | 2626 | |

| Smith* 200672 (1992-2001) | Probability based matching approach using maternal identifiers to link Scottish Morbidity Record, Scottish Stillbirth and Infant Death Enquiry, and prenatal screening database for first pregnancies in West of Scotland (yet have previous miscarriages as risk factor; singleton births) | Scottish Morbidity Record, Scottish Stillbirth and Infant Death Enquiry, and prenatal screening database in Institute of Medical Genetics | Height from Scottish Morbidity Registry, weight from biochemical database | NR | >30 (v 20-24) | NR | NR | |

| Smith 200766 (1991-2001) | Women who had record in prenatal screening database, could be linked to Scottish Morbidity Record, had given birth to singleton weighing >400 g between 22 and 43 weeks | Scotland, UK | Measured | Early pregnancy | >25 | 28 612 | 95 516 | |

| Sukalich 200667 (1998) | Women aged <19 who delivered at 1 of 16 hospitals at >23 weeks | 16 hospitals, New York State, USA | Self report | First antenatal visit | >25 | 1498 | 3324 | |

| Tsukamoto 200768 (2002-3) | Women with singletons 37-42 gestational weeks | Nagai Clinic, Saitama, Sagamihara Kyoudou, Kanagawa in Tokyo metropolitan area, Japan | Self report | Before pregnancy | >25 | 277 | 2301 | |

| Yaacob 200269 (2001) | Randomly selected sample of 276 postnatal women | Women’s Hospital, Doha, Qatar | NR | NR | >30 (v 20-28) | 75 | 75 | |

| Yekta 200670 (2002-3) | Pregnant women who enrolled in public care centres in urban areas during first eight weeks of pregnancy | Urmia, Iran | Self-report | NR | >26 | 100 | 140 | |

| Yogev 200571 (1999-2000) | Consecutive gravid women from maternal health clinics in metropolitan area of San Antonio | Inner city residents of San Antonio, Texas, USA | NR | NR | >27.3 | 1529 | 4861 | |

| Zhou 199775 (1984-7) | All pregnant women with singletons in two geographically well defined areas, who were part of community trial, at 36 weeks of pregnancy | Odense, Aalborg, Denmark | NR | NR | >26 | 648 | 4536 | |

| Total | 337 814‡ | 704 968‡ | ||||||

NR=not reported.

*Studies with data that were not pooled in meta-analyses.

†Cohort studies although data were also presented in format that allowed pooling with case-control data; listed only in table 1 and not table 2.

‡At least this many participants, as some studies did not report numbers exposed and not exposed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of case-control studies included in systematic review and meta-analyses of preterm birth and low birth weight in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Study (period) | Population | Setting | Body mass index | No of women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self report or measured | When recorded | Cases | Controls | ||||

| Al-Eissa* 1994 (one year, date NR) | Live births (birth weight appropriate for gestational age) identified over one year period. Cases: women who delivered preterm infants at 20-37 weeks. Controls: women who delivered infants at 37-42 weeks | King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | NR | NR | 118 | 118 | |

| Begum 200377 (1995) | Cases: women with spontaneous labour who delivered at <37 weeks. Controls: women with spontaneous labour who delivered at >37 weeks | Tertiary hospital, northern India | NR | NR | 94 | 88 | |

| Catov 200778 (1997-2001) | Cases: all women with preterm births (spontaneous onset or premature rupture of membranes). Controls: randomly chosen women delivered >37 weeks, with first blood sample <15 weeks. Both groups: uncomplicated pregnancies | USA | NR | NR | 90 | 199 | |

| Conti 199879 (1994-5) | Cases: consecutive women who delivered premature infants (<37 weeks) with low birth weight (1000-2500 g). Controls: women who delivered infants >2500 g | Major teaching hospital, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia | Self report | During pregnancy | 54 | 86 | |

| de Haas† 199180 (1988-9) | Cases: women who delivered live singletons at 20-37 weeks, with delivery preceded by spontaneous labour or rupture of membrane without induction for maternal or fetal indications | Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA | Measured | NR | 114 | 232 | |

| Delgado-Rodriguez 199881 (1990-3) | Cases: women with live births <2500 g, living in referral area of hospital. Controls: women who delivered singletons >2500 g | University of Granada Hospital, Granada, Spain | Self report (from chart) | NR | 240 | 374 | |

| Dhar 200382 (1999) | Pregnant women who delivered liveborn babies; every third pregnant woman at maternal-child health training institute | Public maternity hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh | Measured | NR | 27 | 167 | |

| Gosselink† 199283 (1985-1990) | Women aged 15-45 who delivered singletons (with spontaneous onset of labour) and consented to be interviewed. Cases: women who delivered preterm. Controls: women who delivered >39 weeks | University of Chicago and University of Iowa Hospitals, USA | Self report | NR | 368 | 368 | |

| Hashim† 200084 (NR) | Randomly selected postpartum women within 24 hours after delivery (at >37 weeks’ gestation). Cases: women who delivered infants <2500 g. Controls: women who delivered infants >2500 g | El-Shemasy Maternity and Children Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | NR | NR | 250 | 250 | |

| Hediger 199585 (Oct 1990 to Nov 1993) | Every third participant enrolled in larger study to prenatal care under same protocol. Women were recruited within one month of entry to have real time and Doppler ultrasound scan for research purposes at 32 weeks | Urban clinic in Camden, New Jersey, USA | Self report | First antenatal visit | 46 | 244 | |

| Karim 199786 (NR) | Women living within four identified sections of Mirpur area with no immediate plans to move from current address, aged 17-35 on date of interview | One hospital: mother and child clinic in Mirpur area of Dhaka, India | Self report | Immediately after birth | 51 | 196 | |

| Lawoyin 199787 (NR) | Consecutive women for whom complete information was available. Cases: women who gave birth to infants <2500 g. Controls: Women who gave birth to babies >2500 g | Armed Forces Hospital, Tabuk, northwest Saudia Arabia | Measured | During pregnancy | 50 | 478 | |

| Le† 200788 (Jul to Dec 2006) | Women who gave birth to singleton live infant, with normal mental health and ability to communicate and had ≥20 teeth. Controls: random sampling | Thai Nguyen Center General Hospital, Thai Nguyen, Thailand | Self report | After birth | 130 | 260 | |

| Melamed 200889 (1996-2004) | All women followed from conception to delivery with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and no diabetes. Cases: women with preterm birth. Controls: women with term deliveries (note called cohort by authors but data extracted for this was case-control) | Rabin Medical Centre, Tel Aviv, Israel | NR | NR | 119 | 329 | |

| Mohsen 200790 (2006) | Pregnant women at delivery and their full term (gestational age 37-42 weeks) newborns. Women without hypertension, diabetes, pregnancy toxaemia, antepartum haemorrhage, or any medical or obstetric problems, with normal vaginal delivery | Al-Mataria Teaching Hospital, Cairo, Egypt | Assumed measured (“Anthropometric measurements of the mother including weight, height and BMI were recorded”) | Post partum | 24 | 30 | |

| Ojha 200791 (2004-5) | Women who delivered at term. Cases: women who delivered low birth weight infants. Controls: women who delivered infants of normal birth weight | Paropakar Shree Panch Indra laxmi Devi Maternity Hospital, Thapathali, Nepal | Measured | Post partum | 154 | 154 | |

| Pitiphat 200892 (1999-2002) | Participants of Project Viva, women with live infants and who were medically insured | One of eight Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates Centers, eastern Massachusetts, USA | Self report | Before pregnancy | 105 | 1530 | |

| Yogev 200793 (1995-9) | Women with singletons and gestational diabetes first diagnosed in the current pregnancy | 1 Hospital: San Antonio Texas, USA | Measured | Before pregnancy | 163 | 1363 | |

| Xue 200894 (2001-2) | White nurses who were cancer free and whose mother reported their birth weight, lived with spouse, received prenatal care, and had singleton pregnancies without pre-eclampsia or eclampsia | Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II USA | Self report | Post partum | 1810 | 30 051 | |

| Zeitlin† 200195 (NR) | Women who delivered live or stillbirth singletons. Cases: women who delivered between 22 and 36 weeks. Controls: every 10th woman who delivered ≥37 weeks | 17 European countries (Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Russia, Scotland, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey) | NR | NR | 4707 | 7821 | |

| Total | 8714 | 44 338 | |||||

NR=not reported.

*Non-pooled study.

†Pooled studies with dichotomous data.

Preterm birth

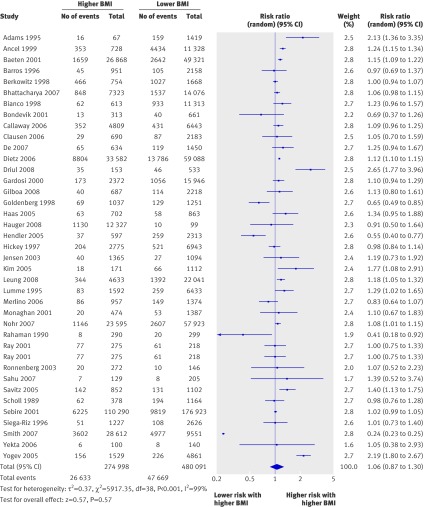

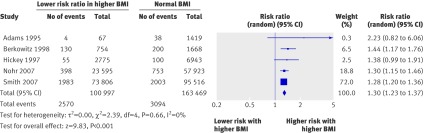

In the pooled cohort studies the overall risk of preterm birth before 37 weeks did not differ significantly among overweight or obese women with singleton pregnancies (relative risk 1.06, 0.87 to 1.30, 38 studies, fig 2) compared with women of normal weight (table 3). However, among overweight and obese women the risk of induced preterm birth was increased (1.30, 1.23 to 1.37, five studies, fig 3). The heavier the woman, the higher the risk of induced preterm birth before 37 weeks, with overweight, obese, and very obese women having a relative risk of 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27), 1.56 (1.42 to 1.71), and 1.71 (1.50 to 1.94), respectively. The risk of spontaneous preterm birth did not differ (0.93, 0.85 to 1.01, 15 studies). Heterogeneity ranged from 0 to 99%, with most studies in the moderate to high range.

Fig 2 Forest plot of risk of preterm birth before 37 weeks in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight in cohort studies. BMI=body mass index

Table 3.

Summary table of preterm birth outcomes in cohort studies of overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Outcomes | Total No of studies | Pooled crude data | Pooled adjusted or matched data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Relative risk* (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies | Relative risk* (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |||

| All births <37 weeks†: | 40 | 38 | 1.06 (0.87 to 1.30)‡ | 99 | 4 | 1.02 (0.68 to 1.54)§ | 77 | |

| Overweight only | 27 | 27 | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) | 48 | 7 | 0.95 (0.85 to 1.06) | 79 | |

| Obese only | 3 | 3 | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.21) | 84 | 1 | 1.17 (1.02 to 1.35) | NA | |

| Very obese only | 6 | 5 | 1.22 (0.86 to 1.72) | 96 | 4 | 1.21 (0.84 to 1.74) | 68 | |

| Spontaneous births <37 weeks: | 15 | 15 | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.01)‡ | 70 | 1 | 2.29 (1.20 to 4.38)§ | NA | |

| Overweight | 10 | 10 | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.97) | 0 | 4 | 0.94 (0.80 to 1.10) | 45 | |

| Obese | 2 | 2 | 0.88 (0.74 to 1.04) | 64 | 2 | 1.04 (0.92 to 1.17) | 94 | |

| Very obese | 2 | 2 | 0.87 (0.70 to 1.07) | 0 | 2 | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.33) | 57 | |

| Induced births <37 weeks: | 5 | 5 | 1.30 (1.23 to 1.37)‡ | 0 | 2 | 1.30 (0.70 to 2.43)§ | 44 | |

| Overweight | 3 | 3 | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) | 29 | 2 | 1.03 (0.72 to 1.48) | 37 | |

| Obese | 1 | 1 | 1.56 (1.42 to 1.71) | NA | 1 | 0.84 (0.71 to 0.98) | NA | |

| Very obese | 1 | 1 | 1.71 (1.50 to 1.94) | NA | 1 | 1.82 (1.47 to 2.26) | NA | |

| Births 32-36 weeks: | 4 | 4 | 1.15 (0.95 to 1.38)‡ | 86 | 1 | 2.16 (1.13 to 4.12)§ | NA | |

| Overweight | 2 | 2 | 0.98 (0.94 to 1.03) | 0 | 1 | 1.21 (0.90 to 1.62) | NA | |

| Obese | 2 | 2 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | 0 | 0 | NA | ||

| Very obese | 2 | 2 | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.09) | 0 | 1 | 2.05 (1.14 to 3.70) | NA | |

| Births <33 weeks: | 12 | 11 | 1.26 (1.14 to 1.39)‡ | 76 | 2 | 1.23 (0.87 to 1.72)§ | 0 | |

| Overweight | 7 | 7 | 1.16 (1.05 to 1.29) | 65 | 4 | 1.08 (0.79 to 1.50) | 90 | |

| Obese | 3 | 3 | 1.45 (1.23 to 1.71) | 57 | 2 | 1.49 (0.89 to 2.50) | 74 | |

| Very obese | 3 | 3 | 1.82 (1.48 to 2.24) | 24 | 2 | 2.02 (1.24 to 3.29) | 0 | |

NA=not applicable.

*Calculated using random effects, inverse variance.

†Spontaneous, induced, and unspecified.

‡Represents pooled relative risk for each of individual rows below and also includes risk in studies that did not stratify by overweight, obese, and very obese, but rather presented combined risk.

§Represents pooled relative risk for studies that originally examined all women with a high body mass index as one group rather than subdividing into overweight, obese, and very obese, as we believe it is methodologically incorrect to pool adjusted risks for overweight women with adjusted risks for obese women within one study. For this reason, the total number of studies for each outcome in adjusted or matched data column is sometimes lower than the number of studies in following rows.

Fig 3 Forest plot of risk of induced preterm birth before 37 weeks in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight in cohort studies. BMI=body mass index

Overweight and obese women had an increased risk of preterm birth before 33 weeks (crude relative risk 1.26, 95% confidence interval 1.14 to 1.39). The heavier the woman, the higher the risk of early preterm birth, with overweight, obese, and very obese women having a relative risk of 1.16 (1.05 to 1.29), 1.45 (1.23 to 1.71), and 1.82 (1.48 to 2.24), respectively.

Compared with the number of studies that presented crude data, few presented matched or adjusted data (table 3). The pooled risks from adjusted or matched data were generally similar in magnitude and direction to that of the pooled crude data—for example, the risk of preterm birth before 37 weeks in overweight or obese women remained non-significant (1.02, 0.68 to 1.54), although the adjusted or matched risk for several outcomes with only one study differed (for example, the adjusted relative risk of spontaneous preterm birth before 37 weeks was 2.29, 95% confidence interval 1.20 to 4.38).

The results of six cohort studies4 25 45 61 72 73 not included in the meta-analysis (the format of the data did not permit pooling) generally supported the pooled data. One study showed an increased risk of preterm birth before 37 weeks45 in overweight and obese women and another showed a slight decreased risk.4 Similar to the pooled data, there were decreases in spontaneous preterm birth before 37 weeks4 72 and increases in the risk of induced preterm birth before 37 weeks.4 54 Preterm birth (32-36 weeks) was significantly increased in overweight and obese women in one study25 but not in another.61 Unlike the pooled data there was no significant increase in preterm birth before 32 weeks.4 25 61

Data from seven case-control studies that examined maternal body mass index as a continuous variable also generally supported the findings of the cohort data. The mean body mass index of women with preterm birth before 37 weeks overall did not differ significantly from those with term births (−0.33 body mass index unit, −1.19 to 0.53), although women with spontaneous preterm birth had a slightly lower body mass index (−0.90, −1.77 to −0.02; table 4).

Table 4.

Perinatal outcomes in case-control studies according to difference in maternal body mass index

| Outcome | Total No of studies | Pooled crude data | Pooled matched data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Mean difference of body mass index (95% CI)* | I2 (%) | No of studies | Mean difference of body mass index (95% CI)* | I2 (%) | |||

| Preterm births | ||||||||

| Birth <37 weeks: | 7 | 6 | −0.33 (−1.19 to 0.53) | 86 | 1 | −0.70 (−2.23 to 0.83) | NA | |

| Spontaneous birth | 4 | 0 | −0.90 (−1.77 to −0.02) | 82 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Preterm birth <33 weeks | 2 | 2 | 0.72 (−2.16 to 0.73) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Low birth weight | ||||||||

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 8 | 7 | −1.15 (−1.87 to −0.44) | 84 | 1 | −1.20 (−1.85 to −0.55) | NA | |

| Intrauterine growth restriction§ | 2 | 1 | −1.70 (−2.64 to −0.76) | NA | 1 | −0.60 (−2.42 to 1.22) | NA | |

NA=not applicable.

*Calculated using random effects, inverse variance.

†No values for induced preterm birth before 37 weeks or birth 32-33 to 36 weeks.

‡No values for birth weights of 1500-2500 g, <1500 g, or <1000 g.

§Less than 10% for gestational age.

A few case-control studies reported body mass index as a dichotomous variable (high versus reference; table 5) There was a trend towards preterm birth before 37 weeks in overweight or obese women overall (crude odds ratio 1.16, 95% confidence interval 0.99 to 1.37), although not in the matched data (odds ratio 1.08, 0.39 to 2.95). The risk of spontaneous preterm birth in overweight or obese women was increased in those in the matched data (1.79, 1.73 to 2.84) but not the crude data (1.00, 0.18 to 5.53). One case-control study that could not be pooled found a trend towards decreased spontaneous preterm birth (crude odds ratio 0.58, 95% confidence interval 0.33 to 1.03).

Table 5.

Risk of poor perinatal outcomes in case-control studies of overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Outcome* | Pooled crude data | Pooled matched data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Odds ratio (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies | Odds ratio (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ||

| Preterm birth <37 weeks | 2 | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.37) | 0 | 2 | 1.08 (0.39 to 2.95) | 89 | |

| Spontaneous preterm birth <37 weeks | 1 | 1.00 (0.18 to 5.53) | NA | 1 | 1.79 (1.13 to 2.84) | NA | |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 1 | 0.51 (0.36 to 0.74) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |

NA=not applicable.

*No values for induced preterm births before 37 weeks, births 32-36 weeks, and births before 32 weeks; birth weights of 1500-2500 g, <1500 g, and <1000 g; intrauterine growth restriction; mean birth weight; and gestational age at delivery.

†Calculated using random effects, Mantel Haenszel.

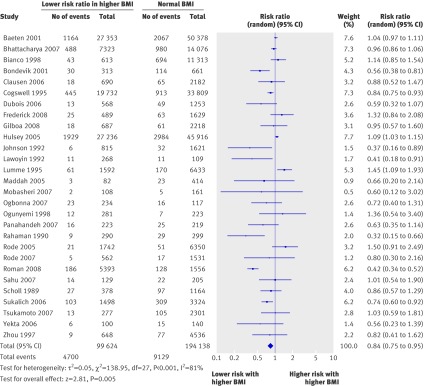

Low birth weight

In the pooled cohort studies, overweight and obese women had a decreased risk of having an infant of low birth weight (relative risk 0.84, 95% confidence interval 0.75 to 0.95, 28 studies, fig 4) but an increased risk of having an infant of very low birth weight (<1500 g, 1.61, 1.42 to 1.82, two studies) or extremely low birth weight (<1000 g, 1.31, 1.08 to 1.59, one study; table 6). The heavier the woman, the higher the risk of having an extremely low birth weight infant, with relative risks in overweight, obese, and very obese women of 1.18 (0.94 to 1.47), 1.43 (1.05 to 1.95), and 1.98 (1.36 to 2.89), respectively.

Fig 4 Forest plot of risk of having an infant of low birth weight (<2500 g) in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight in cohort studies. BMI=body mass index

Table 6.

Risk of low birth weight and other perinatal outcomes in cohort studies of overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Outcome | Total No of studies | Pooled crude data | Pooled matched data | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Relative risk* (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies | Relative risk* (95% CI) | I2 (%) | |||

| All low birth weight (<2500 g)†: | 31 | 28 | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.95)‡ | 81 | 4 | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.93) | 20 | |

| Overweight | 21 | 21 | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.05) | 73 | 4 | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.19) | 0 | |

| Obese | 4 | 4 | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.19) | 92 | 1 | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.33) | NA | |

| Very obese | 6 | 5 | 0.81 (0.42 to 1.53) | 88 | 1 | 0.30 (0.09 to 1.01) | NA | |

| Moderately low birth weight (1500-2500 g)§: | 1 | 1 | 0.99 (0.93 to 1.05)‡ | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Overweight | 1 | 1 | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.13) | NA | 1 | 0.95 (0.64 to 1.41) | NA | |

| Very low birth weight (<1500 g)¶: | 2 | 2 | 1.61 (1.42 to 1.82)‡ | 0 | 0 | NA | ||

| Overweight | 1 | 1 | 1.42 (1.18 to 1.70) | NA | 1 | 1.54 (1.22 to 1.94) | NA | |

| Very obese | 1 | 1 | 1.54 (0.75 to 3.15) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Extremely low birth weight (<1000 g): | 1 | 1 | 1.31 (1.08 to 1.59)‡ | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Overweight | 1 | 1 | 1.18 (0.94 to 1.47) | NA | 1 | 1.27 (0.93 to 1.74) | NA | |

| Obese | 1 | 1 | 1.43 (1.05 to 1.95) | NA | 1 | 1.55 (0.99 to 2.44) | NA | |

| Very obese | 1 | 1 | 1.98 (1.36 to 2.89) | NA | 1 | 2.80 (1.72 to 4.57) | NA | |

| Intrauterine growth restriction**: | 11 | 9 | 0.79 (0.72 to 0.88)‡ | 58 | 3 | 1.15 (0.79 to 1.66) | 0 | |

| Overweight | 7 | 7 | 0.79 (0.73 to 0.86) | 34 | 2 | 0.69 (0.63 to 0.76) | 0 | |

| Obese | 1 | 1 | 1.01 (0.77 to 1.30) | NA | 0 | NA | ||

| Very obese | 3 | 2 | 0.81 (0.61 to 1.08) | 0 | 1 | 1.06 (0.18 to 6.31) | NA | |

| Mean difference in birth weight (g): | 10 | 9 | 70.8 (54.5 to 87.2)‡ | 89 | 1 | 172.0 (137.1 to 206.9) | NA | |

| Overweight | 7 | 7 | 68.2 (50.0 to 86.4) | 92 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Obese | 1 | 1 | 25.0 (−41.2 to 91.2) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Very obese | 2 | 2 | 49.9 (−30.5 to 130.4) | 62 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Mean difference in gestational age at delivery (weeks): | 6 | 5 | −0.06 (−0.12 to −0.01)‡ | 0 | 1 | 0.00 (−0.14 to 0.14) | NA | |

| Overweight | 3 | 3 | −0.08 (−0.16 to 0.00) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Obese | 1 | 1 | 0.10 (−0.13 to 0.33) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Very obese | 2 | 2 | −0.05 (−0.18 to 0.08) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | |

NA=not applicable.

*Calculated using random effects, inverse variance. Total number of studies for each outcome are sometimes lower than number of studies in following rows (for explanation see footnote to table 3).

rows below and also includes risk in studies that did not stratify by overweight, obese, and very obese, but rather presented combined risk.

†Of all babies, including those of low birth weight at term and preterm.

‡Represents pooled relative risk for each of individual.

§No values for obese and very obese women.

¶No values for obese women.

**Less than 10% for gestational age.

Two cohort studies with non-pooled data showed similar risks of low birth weight in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight (adjusted odds ratios 1.4, 95% confidence interval 0.9 to 2.145 and 0.3, 0.1 to 1.0).73

In the seven pooled case-control studies women with low birth weight singletons had a lower maternal body mass index than women with singletons of appropriate weight in both the crude data (−1.15 body mass index units, 95% confidence interval −1.87 to −0.44) and the single study of matched data (−1.20, −1.85 to −0.55; table 4). The single case-control study that dichotomised body mass index into high versus reference also found a decreased risk of infants with low birth weight among mothers with a high body mass index (odds ratio 0.51, 95% confidence interval 0.36 to 0.74; table 5).

Other outcomes

In the pooled cohort studies, overweight and obese women had a lower risk of infants with intrauterine growth restriction than women of normal weight (crude relative risk 0.79, 0.72 to 0.88, table 6), and infants with higher mean birth weights by 70.8 g (54.4 g to 87.2 g) despite shorter mean gestations (by −0.06 weeks, 95% confidence interval −0.12 weeks to −0.01 weeks).

One case-control study reported that women with singletons showing intrauterine growth restriction had a lower mean body mass index than women with infants of normal growth (−1.70 body mass index units, 95% confidence interval −2.64 to −0.76; table 4).

A priori defined sensitivity analyses for preterm birth

Many of the categories in the sensitivity analyses had few studies, limiting our power to draw conclusions. In developing countries, the risk of preterm birth in overweight and obese women were similar to those of women in developed countries (relative risk 0.83, 95% confidence interval 0.61 to 1.12 and 1.09, 0.87 to 1.36; table 7).

Table 7.

Sensitivity analyses for preterm birth in cohort studies of overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Outcomes | All studies | Overweight | Obese | Very obese | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ||||

| Developed countries‡ | 31 (728 566) | 1.09 (0.87 to 1.36) | 99 | 22 (699 905) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) | 57 | 3 (200 753) | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.21) | 84 | 5 (201 485) | 1.22 (0.86 to 1.72) | 96 | |||

| Developing countries‡ | 8 (18 578) | 0.83 (0.61 to 1.12) | 32 | 5 (12 591) | 1.05 (0.80 to 1.36) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 1 (488) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.75) | NA | |||

| Low quality studies | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | |||||||

| Other quality studies | 40 (845 165) | 1.13 (1.01 to 1.26) | 97 | 27 (712 496) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) | 48 | 3 (200 753) | 1.10 (0.99 to 1.21) | 84 | 6 (201 973) | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.62) | 95 | |||

| Adolescence | 1 (1542) | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.28) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||

| Adults | 4 (24 146) | 1.09 (0.95 to 1.25) | 15 | 2 (2269) | 0.92 (0.65 to 1.30) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 1 (11 926) | 1.23 (0.96 to 1.57) | NA | |||

| Black women | 1 (4300) | 0.84 (0.69 to 1.03) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||

| White women | 1 (3495) | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.38) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||

| Body mass index | |||||||||||||||

| Self reported | 16 (306 500) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.18) | 56 | 9 (151 826) | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.10) | 0 | 1 (72 998) | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.17) | NA | 2 (77 758) | 1.24 (1.19 to 1.29) | 0 | |||

| Measured | 8 (476 645) | 1.22 (0.87 to 1.72) | 99 | 6 (432 550) | 0.97 (0.94 to 0.99) | 0 | 2 (127 755) | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 85 | 3 (123 727) | 1.23 (0.58 to 2.65) | 96 | |||

| Prepregnancy | 28 (347 010) | 1.11 (1.04 to 1.19) | 81 | 20 (259 522) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) | 19 | 1 (72 998) | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.17) | NA | 3 (84 449) | 1.24 (1.19 to 1.29) | 0 | |||

| During pregnancy | 10 (494 457) | 1.13 (0.81 to 1.56) | 99 | 6 (450 047) | 0.97 (0.94 to 1.00) | 8 | 2 (127 755) | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 85 | 3 (117 524) | 0.77 (0.29 to 2.03) | 95 | |||

| Post partum | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||

| Cut-off values: | |||||||||||||||

| 20-25, 25-30 | 9 (441 974) | 0.94 (0.53 to 1.65) | 100 | 9 (504 179) | 0.99 (0.96 to 1.03) | 32 | 2 (127 755) | 1.08 (0.90 to 1.30) | 85 | 3 (123 727) | 1.23 (0.58 to 2.65) | 96 | |||

| Close to 20-25, 25-30 | 25 (267 008) | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.09) | 91 | 18 (208 317) | 1.06 (0.99 to 1.13) | 27 | 1 (72 998) | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.17) | NA | 1 (65 832) | 1.24 (1.19 to 1.29) | NA | |||

| Not close to 20-25, 25-30 | 6 (52 088) | 1.12 (0.83 to 1.51) | 92 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 2 (12 414) | 0.43 (0.03 to 5.19) | 84 | |||

No studies were of low quality. NA=not applicable.

*Crude and matched data were pooled for sensitivity analyses.

†Calculated using random effects, inverse variance.

‡Assigned according to Central Intelligence Agency16 criteria. Zeitlin95 included 17 European countries that comprised both developed and developing countries and hence was not included in sensitivity analyses for developing and developed countries.

No studies were of low quality. There was no significant increase in preterm birth among adolescents compared with adults (0.98, 0.76 to 1.28, one study, and 1.09, 0.95 to 1.25, four studies). Only one study reported on ethnicity; the risk of preterm birth was not significantly increased in overweight and obese black women (0.84, 0.69 to 1.03) or white women (1.03, 0.77 to 1.38).

A priori defined sensitivity analyses for low birth weight

The decreased risk of low birth weight in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight in developing countries was greater than in developed countries (0.58, 0.47 to 0.71, 11 studies v 0.90, 0.79 to 1.01, 20 studies; table 8). In developing countries, the heavier the woman the smaller the risk of having an infant of low birth weight: relative risks for overweight, obese, and very obese women were, respectively, 0.88 (0.64 to 1.23), 0.39 (0.11 to 1.34), and 0.29 (0.10 to 0.89).

Table 8.

Sensitivity analyses for low birth weight in cohort studies of overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Outcomes | All studies | Overweight | Obese | Very obese | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† 95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | No of studies* (No of women) | Relative risk† (95% CI) | I2 (%) | ||||||

| Developed countries‡ | 20 (293 806) | 0.90 (0.79 to 1.01) | 85 | 15 (221 318) | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.07) | 80 | 3 (22 766) | 0.69 (0.34 to 1.37) | 94 | 4 (32 364) | 0.85 (0.44 to 1.65) | 91 | |||||

| Developing countries‡ | 11 (4710) | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.71) | 0 | 6 (1549) | 0.88 (0.64 to 1.23) | 0 | 1 (186) | 0.39 (0.11 to 1.34) | NA | 2 (615) | 0.29 (0.10 to 0.89) | 0 | |||||

| Low quality studies | 1 (150) | 0.60 (0.23 to 1.57) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||||

| Remainder of studies | 30 (298 366) | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.93) | 82 | 21(222 867) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.05) | 73 | 4 (22 952) | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.19) | 92 | 6 (32 979) | 0.72 (0.39 to 1.31) | 86 | |||||

| Adolescents | 2 (6364) | 0.76 (0.63 to 0.92) | 0 | 1 (4305) | 0.75 (0.58 to 0.96) | NA | 1 (3671) | 0.78 (0.52 to 1.15) | NA | 1 (3494) | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.17) | NA | |||||

| Adults | 3 (14 515) | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42) | 0 | 1 (1708) | 2.04 (0.69 to 5.98) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||||

| Black women§ | 1 (504) | 1.36 (0.54 to 3.40) | NA | 1 (301) | 2.86 (1.04 to 7.89) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||||

| Infant born at term | 4 (10 580) | 0.93 (0.57 to 1.53) | 59 | 3 (8260) | 1.28 (0.72 to 2.27) | 41 | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||||

| Infant born at term and preterm | 28 (289 478) | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.91) | 28 | 18 (214 607) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.03) | 76 | 4 (22 952) | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.19) | 92 | 6 (32 979) | 0.72 (0.39 to 1.31) | 86 | |||||

| Body mass index | |||||||||||||||||

| Self reported | 17 (177 230) | 0.88 (0.77 to 1.01) | 65 | 12 (131 837) | 0.93 (0.83 to 1.04) | 17 | 1 (3671) | 0.78 (0.52 to 1.15) | NA | 2 (15 420) | 0.90 (0.51 to 1.60) | 66 | |||||

| Measured | 4 (29 076) | 0.60 (0.34 to 1.07) | 94 | 4 (24 094) | 0.66 (0.41 to 1.06) | 87 | 3 (22 766) | 0.69 (0.34 to 1.37) | 94 | 3 (17 071) | 0.70 (0.19 to 2.61) | 93 | |||||

| Prepregnancy | 24 (271 847) | 0.84 (0.74 to 0.97) | 83 | 17 (200 246) | 0.92 (0.78 to 1.08) | 77 | 3 (7018) | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.92) | 76 | 5 (18 746) | 0.57 (0.30 to 1.08) | 82 | |||||

| During pregnancy | 4 (25 579) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.10) | 60 | 3 (22 382) | 0.89 (0.79 to 1.00) | 0 | 1 (15 934) | 1.10 (0.93 to 1.30) | NA | 1 (14 233) | 1.74 (1.14 to 2.66) | NA | |||||

| Post partum | 1 (351) | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.31) | NA | 1 (239) | 0.96 (0.50 to 1.83) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | |||||

| Cut-off values: | |||||||||||||||||

| 20-25, 25-30 | 5 (110 404) | 1.02 (0.88 to 1.19) | 69 | 3 (78 291) | 1.08 (0.73 to 1.61) | 81 | 2 (16 120) | 0.79 (0.30 to 2.04) | 63 | 2 (14 360) | 1.06 (0.19 to 5.88) | 48 | |||||

| Close to 20-25, 25-30 | 22 (167 456) | 0.74 (0.62 to 0.88) | 84 | 17 (136 928) | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.03) | 75 | 2 (6832) | 0.53 (0.26 to 1.09) | 88 | 2 (6205) | 0.47 (0.32 to 0.70) | 31 | |||||

| Not close to 20-25, 25-30 | 4 (20 656) | 0.95 (0.58 to 1.56) | 60 | 1 (7648) | 1.06 (0.55 to 2.02) | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 2 (12 414) | 0.67 (0.18 to 2.45) | 78 | |||||

NA=not applicable.

*Crude and matched data were pooled for sensitivity analyses.

†Calculated using random effects, inverse variance.

‡Assigned according to Central Intelligence Agency16criteria and Zeitlin95 included 16 European countries that comprised both developed and developing countries and hence was not included in sensitivity analyses for developing and developed countries.

§No values for white women.

Only one study was of low quality, limiting conclusions on the effect of study quality. Overweight and obese adolescents but not adults were at a decreased risk of having an infant of low birth weight (0.76, 0.63 to 0.92 v 1.0.8, 0.82 to 1.42).

No studies specified whether their population was white and therefore the effect of ethnicity on low birth weight could not be examined.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment (tables 9 and 10) was based on the evaluation of six types of bias. Selection bias was unlikely as women with high and normal body mass indices were usually drawn from the same populations, whereas exposure bias was possible given that weight was self reported in most studies.

Table 9.

Quality assessment based on evaluation of bias in cohort studies of preterm birth and low birth weight in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Study | Selection bias | Exposure bias | Outcome assessment bias | Confounding factor bias* | Analytical bias | Attrition bias | Overall likelihood of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abenhaim† 200725 | Low | Low | Low | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, smoking, diabetes | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Adams 19959 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Low. Assessed but not different: parity, smoking, race, sex of infant, marital status. Adjusted for medical centre | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Ancel 199954 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Low. Adjusted for country of residence. Assessed, but not different: NR. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: age, education, social class, smoker, previous preterm birth, marital status, previous abortion | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Baeten 200159 | Minimal | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, education, smoking, pre-eclampsia, insurance, marital status | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Barros 199651 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | NA (primary exposure not anthropometry) | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Berkowitz 199826 | Low | Low | Low | Minimal. Adjusted for age, smoking, insurance, drug use, birth place, clinic service, prenatal care began >12 weeks. Assessed, but not different: in vitro fertilisation. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: diabetes, hypertension | NR | Low | Low |

| Bhattacharya 200727 | Low | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, year of delivery, gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia, induced labour. Assessed, but not different: age, husband’s social class, diabetes. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: booking week, height, married or cohabiting, smoking | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Bianco 199860 | Low | Low | Low | Low. Assessed, but not different: age. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for parity, education, hypertension, diabetes, substance misuse, race, marital status, clinical service | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Bondevik 200128 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | NA (primary exposure not anthropometry) | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Callaway 200629 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, smoking, race | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Clausen 200630 | Low | NR | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for low birth weight, age, parity, education, smoking, Oslo east, living alone. For preterm birth: parity, smoking, living alone | Low | NR | Low |

| Cogswell 199550 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, sex of the infant, gestational age, maternal height, drinking status, race | Moderate | Minimal | Moderate |

| Cnattingius† 199861 | Minimal | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, smoking, total weight gain, height, mother living with father | Low | Minimal | Low |

| De 200748 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | NA (primary exposure not anthropometry) | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Dietz 200624 | Minimal | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for parity, race, marital status, Medicaid recipient | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Driul 200831 | Low | Low | Low | Moderate (potential confounders not assessed by original study)† | NR | Minimal | Moderate |

| Dubois 200632 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Low. Matched for age, gestational age | Low | Low | Low |

| Frederick 200846‡ | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Matched for age, education, smoking, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, race, marital status, preterm birth, sex of infant | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Gardosi 200033 | Low | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, smoking, weight at first visit, race, history of abortion, alcohol use | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Gilboa 200834 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, smoking, pre-eclampsia, alcohol use, race of infant, sex of infant | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Goldenberg 199810 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: age, previous abortion, education, smoker, pelvic pressure, drug or alcohol use, urinary tract infection, most medical complication, diarrhoea | Low | Low | Low |

| Haas 200555 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, country of birth, race/ethnicity, level of education, parity, site of care, body mass index, before pregnancy: physical function, depressive symptoms, chronic health conditions, level of exercise, and smoking status, during pregnancy: smoking status, physical function, depressive symptoms, use of illicit drugs, eclampsia or pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, other pregnancy complications, and inadequate prenatal care | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Hauger 200811 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, smoking, pre-eclampsia, diabetes, gestational diabetes, hypertension, caesarean section, number of prenatal visits | Minimal | Moderate | Low |

| Hendler 200557 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, smoking, ethnicity, prepregnancy body mass index, previous preterm birth | Minimal | Minimal | Low |

| Hickey 199735 | High | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, smoking, previous preterm birth last birth, height | Moderate | Minimal | Moderate |

| Hulsey 200536 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for hypertension, ethnicity, diabetes, use of prenatal care, Women’s, Infants, and Children (special supplemental food programme for women, infants, and children) participation, intention of pregnancy | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Jensen 200321 | Minimal | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, smoking, gestational diabetes, race, clinical centre, weight gain, gestational age | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Johnson 199258 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Matched for ethnicity, marriage, tobacco, alcohol, drugs, parity, sex of fetus | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Kim 200547 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for nulliparous women: income, passive smoking, body mass index, vaginal bleeding, coffee drinking, drug misuse. For multiparous women: vaginal bleeding, alcohol misuse, previous spontaneous abortion, previous preterm delivery, previous pre-eclampsia, drug misuse, housework | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Kumari 200122 | Low | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Matched for age, parity. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: pregnancy induced hypertension, diabetes, gestational diabetes | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Lawoyin 1992 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Moderate (potential confounders not assessed by original study)* | NR | Low | Moderate |

| Leung 20086 | Low | Low | Low | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, diabetes, year delivered, previous caesarean section, gestational age at booking | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Lumme 199538 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, smoking, race | Low | Low | Low |

| Maddah 200544 | Moderate | Minimal | NR | Moderate (potential confounders not assessed by original study)* | Moderate | Minimal | Moderate |

| Merlino 200639 | Low | Low | Low | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: preterm birth, gestational age. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for age | High | Minimal | Moderate |

| Mobasheri 200749 | Low | Minimal | NR | Low. Assessed, but not different: working status. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for education | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Monaghan 200140 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, placental complications, pre-existing hypertension, net pregnancy weight gain <10 kg, not married, secondary education or less | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Nohr 200723 | Minimal | Minimal | Low | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, social-occupational status, mother’s height, alcohol use, smoking | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Ogbonna 200741 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, marital status, gravidity, human immunodeficiency virus, malaria infection, multivitamin use | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Ogunyemi 199862 | Low | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for body mass index, neonatal intensive care, previous low birth weight suspect. Adjusted for previous cesarean, previous fetal death, asthma, caesarean delivery, vomiting, pre-eclampsia, hypertension | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Panahandeh 200752 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, working status, pregnancy body mass index, height | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Panaretto† 200645 | Low | Minimal | Low | Low. Assessed, but not different: for preterm birth: hypertension, interval between pregnancies. For low birth weight: drug use. For small for gestational age: drug use, age | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Rahaman 199056 | Low | NR | NR | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: pre-eclampsia, hypertension, medical complication, diabetes. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: age, gestational age | Low | Minimal | Moderate |

| Ray 200120 | Low | Minimal | Low | Minimal. Adjusted for diabetes class, age, parity, hypertension, previous preterm birth, history of caesarean section or uterine surgery, history of neonatal death or stillbirth, net weight gain during pregnancy | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Rode 200564 | Minimal | NR | Low | Moderate. Adjusted for pre-eclampsia | NR | Minimal | Moderate |

| Rode 200753 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: marital status, alcohol intake, caffeine intake, gestational age. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: age, parity, education, smoking, pre-eclampsia, weight gain | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Roman 200742 | Low | Minimal | Low | Minimal. Matched for age, parity. Assessed, but not different: fetal malformation, pregnancy termination. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: pre-eclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, diabetes, gestational diabetes, hypertension, race | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Roman 20083 | Low | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, race, insurance, prenatal care | NR | Low | Low |

| Ronnenberg 200343 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, education, sex of infant, height, work stress, maternal exposure to dust or noise or passive smoking | Low | NR | Low |

| Sahu 20075 | Low | Minimal | NR | Low. Assessed, but not different: sex of fetus. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: gestational diabetes, pregnancy induced hypertension, anaemia | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Salihu† 20084 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Matched for age, parity, education, smoking, year delivery, race, marital status, adequacy of prenatal care, gender of infant, maternal height, weight gain. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: hypertension, anaemia, pre-eclampsia, diabetes, placental abruption, placenta previa | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Savitz 20052 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education, smoking, race, previous preterm birth, marital status, poverty index | Low | Minimal | low |

| Sayers† 199773 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for smoking, male infant, aboriginal ancestor | Moderate | Minimal | Low |

| Scholl 198974 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, age, weight gain adequacy, smoking, ethnicity; for preterm birth: age, weight gain adequacy, previous preterm birth, adequacy of prenatal care. Assessed, but not different: clinical pay status, parity | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Sebire 200163 | Minimal | Low | Low | Minimal. Matched for age, parity, smoking, pre-eclampsia, pre-existing diabetes, gestational diabetes, race, hypertension | Moderate | Minimal | Low |

| Siega-Riz 199665‡ | Low | Minimal | NR | Moderate. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: education, hypertension, smoking, marital status, race | Low | Minimal | Moderate |

| Smith† 200672 | Minimal | Low | Low | Low (because assumed). Assessed, but not different: age. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for (assumed from table 2) α fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotrophin, smoking, previous miscarriage, marital status, previous therapeutic abortions | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Smith 200766 | Minimal | Low | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, smoking, marital status, maternal height, deprivation category, previous spontaneous early pregnancy losses, and therapeutic abortions | Minimal | Minimal | Low |

| Sukalich 200667 | Minimal | Low | Low | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: age, smoking, diabetes, previous caesarean section. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: parity, hypertension, medical, maternal weight gain, race | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Tsukamoto 200768 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, maternal weight gain. Assessed, but not different: pregnancy induced hypertension. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled for: gestational diabetes | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Yaacob 200269 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Low. Matched for age, parity. Assessed, but not different: hypertension, gestational diabetes | High | NR | High |

| Yekta 200670 | Low | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, education | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Yogev 200571 | Low | Minimal | NR | Moderate (potential confounders not assessed by original study)* | Low | Minimal | Moderate |

| Zhou 199775 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Moderate (confounders not assessed)* | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

NR=not reported; NA=not applicable.

*Assessment of confounding factor bias was done by evaluation of each studies’ assessment of potential confounders by four methods: adjustment with regression, matching, assessment of potential confounders on univariate analyses that were found to be not significantly different between groups, and assessment of potential confounders on univariate analyses that were different between groups and not controlled for.

‡Although these were cohort studies, data within manuscript were also presented in format that allowed pooling with data from case-control studies; however, data are listed only in tables with cohort studies.

Table 10.

Quality assessment based on evaluation of bias in case-control studies of preterm birth and low birth weight in overweight and obese women compared with women of normal weight

| Study | Selection bias | Exposure bias | Outcome assessment bias | Confounding factor bias* | Analytical bias | Attrition bias | Overall likelihood of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Eissa† 1994 | Low | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Adjusted for age <20 years, previous preterm birth, previous low birth weight, mud house as dwelling, first or second degree relatives, non-relatives, previous spontaneous abortion, inadequate prenatal care, antepartum haemorrhage, interval between pregnancies <12 months, vaginal bleeding in first or second trimester | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Begum 200377 | Minimal | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: age, parity, previous preterm birth, gravida, previous abortion. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled: income, education | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Catov 200778 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Moderate (confounders not assessed)* | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Conti 199879 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Matched for age, parity, insurance | Low | Minimal | Low |

| de Haas* 199180 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Matched for age, delivery date, education, marital status, race | High | Low | Moderate |

| Delgado-Rodriguez 199881 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: age, parity, smoking. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled: education, social class, pregnancy induced hypertension | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Dhar 200382 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, parity, antenatal care, birth to conception interview, sex of new born, gestational age, hypertension, body mass index after delivery, weight, haemoglobin level, mean arm circumference, income, education, father’s education, father’s occupation | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Gosselink* 199283 | Low | Minimal | NR | Minimal. Matched for age, parity, race | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Hashim* 200084 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: parity, education, social class, antenatal visits, newborn sex, presence of household helper, occupation, consanguinity. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled: age | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Hediger 199585 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Assessed, but not different: smoking, maternal height, prepregnancy body mass index, gestational age at delivery, medical recipient, primiparous women | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Karim 199786 | Moderate | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for age, education, income. Assessed, but not different: parity, age of last surviving child, husband’s occupation, place of delivery. Confounders assessed, different, and not controlled: sex of child | Low | Minimal | Moderate |

| Lawoyin 199787 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Low. Assessed, but not different: haemoglobin level | Low | Low | Low |

| Le* 200788 | Low | Minimal | Low | NA (primary exposure not anthropometry) | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Melamed 200889 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | NA ( primary exposure not anthropometry) | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Mohsen 200790 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Moderate (confounders not assessed)* | Low | Minimal | Moderate |

| Ojha 200791 | Low | Minimal | Minimal | Low. Matched for age, parity | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Pitiphat 200892 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | NA (primary exposure not anthropometry) | NR | Minimal | Low |

| Yogev 200793 | Low | Minimal | NR | NA (primary exposure not anthropometry) | Low | Minimal | Low |

| Xue 200894 | Low | Low | Minimal | Moderate (confounders not assessed)* | NR | Minimal | Moderate |

| Zeitlin* 200195 | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal | Minimal. Adjusted for obstetric history, marital status, body mass index <18.3 or >29.8, smoking in third trimester, age at completion of schooling | Low | Minimal | Low |

*Confounding factor bias was done by evaluation of each studies’ assessment of potential confounders by four methods (see footnote to table 9).

†Non-pooled study.

Little bias was present in our outcomes as they had standard definitions and were objectively measured—for example, low birth weight was always defined as birth weight <2500 g.

Confounding variables that might explain part or all of the relation between overweight and obesity and preterm birth and low birth weight were incompletely dealt with in several ways: by exclusion, by matching, by comparison of some variables and determining that they were not significantly different between the exposed and unexposed women, and by using multiple regression to control for some variables that were significantly different between the two groups. Most studies assessed some confounding variables, but none addressed all. Many studies did not calculate a sample size or power calculation. Attrition bias was rare given that follow-up occurred during the hospital admission for birth.

Trim and fill analyses

The trim and fill analysis of preterm birth before 37 weeks suggested that nine studies were “missing” from the initially meta-analysed relative risk of 1.06 (95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.30); when the nine studies were imputed yielding a risk based on a total of 49 studies, the risk of preterm birth before 37 weeks was significantly higher in overweight and obese women than normal weight women (1.24, 1.13 to 1.37, see web extra appendix 4). The trim and fill analysis resulted in no additional imputed studies for preterm birth before 32 weeks (with the original studies showing an increased risk in overweight or obese mothers). The risk of spontaneous preterm birth in overweight or obese women was similar with four additional imputed studies (0.89, 0.81 to 0.97). After accounting for publication bias, the apparent protective effect of overweight or obesity on low birth weight disappeared with the addition of nine imputed studies, yielding an overall risk based on 40 studies (0.95, 0.85 to 1.07, see web extra appendix 4).

Discussion