Abstract

We report the construction of novel temperature-responsive assemblies based on a double hydrophilic block copolymer (consisting of a PEG block and a β-cyclodextrin-containing block, PEG-b-PCD) and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm). Thus formed nano-assemblies exhibit a spherical morphology and have a temperature-responsive loose core. The driving force for the formation of these assemblies was found to be the inclusion complexation interaction between the hydrophobic cavity of β-cyclodextrin and the isopropyl group of PNIPAm. The particle size of these assemblies changed reversibly in response to the external temperature change. The particle size also changed with the PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD weight ratio. A model hydrophobic drug (indomethacin) was loaded into these assemblies with a high efficiency. An in vitro release study showed that the payload could be released in a sustained manner after an initial burst release. The release rate could be switched between high and low in an ON/OFF fashion by temperature. These results demonstrate that the nano-assemblies have high potential for applications in controlled drug delivery and biomedicine when temperature responsiveness is desired.

Introduction

During the past two decades, stimuli-responsive assemblies such as polymeric micelles, polymersomes, nanotubes, capsules and liposomes, have attracted much attention due to their potential applications in biomedicine, pharmaceutics, cosmetics and biotechnology.1-5 The stimulative factors employed in these assemblies include temperature, pH, light, magnetic field, sound (ultrasound), and chemical or biological signals.6-17 Temperature-responsive assemblies are of particular interest and may be used in a variety of applications such as encapsulation, controlled delivery, gene transfection, imaging, or as intelligent switches.18-25 In addition to liposomes,23, 26 polymeric assemblies with thermo-sensitivity have been extensively studied in recent years.1, 19 To construct these nano-objects by self-assembly, temperature-responsive graft or block copolymers with poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) as a responsive segment/block are frequently synthesized.1, 7, 21, 22, 27-29 Subsequent dissolution or dialysis procedure leads to the formation of assemblies with temperature-responsive outer shells.

On the other hand, the host-guest interactions of cyclodextrins (CDs) and a wide range of hydrophobic molecules has been widely employed to construct functional supramolecular assemblies.30 For instance, supramolecular polymers, chemo-responsive and switchable hydrogels, hollow spheres, reversible assemblies, and drug/gene carriers have been developed by utilizing the inclusion complexation between cyclodextrins and selected hydrophobic molecules.31-37 However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no prior research report on the spontaneous formation of temperature responsive nano-assemblies from cyclodextrin-containing homopolymers or copolymers. In this study, with an aim to develop a novel thermosensitive system, we designed and synthesized a block copolymer with one PEG block and one β-cyclodextrin-containing block. The evidence from TEM observation revealed that spherical assemblies were formed spontaneously when the copolymer and PNIPAm were dissolved together in water, which was mediated by inclusion complexation interactions between the isopropyl groups of PNIPAm and β-cyclodextrins conjugated on the side chains of the block copolymer. These newly developed polymeric carriers were thermosensitive due to their temperature responsive cores rather than temperature-sensitive shells reported by other groups.

Experimental

Materials

L-Aspartic acid β-benzyl ester was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA). Triphosgene was obtained from Fisher (USA). β-Benzyl-L-aspartate N-carboxyanhydride (BLA-NCA) was synthesized according to the literature with a yield of 83%.38 α-Methoxy-ω-amino-polyethylene glycol (MPEG-NH2) with an average Mw of 5000 was purchased from Laysan Bio, Inc. (Alabama, USA), and used without further purification. Ethylenediamine (EDA) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, USA) and distilled over CaH2 under decreased pressure. β-cyclodextrin (β-CD, ≥98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (USA) and used as received. The method established by Baussanne et al. was employed to synthesize 6-monotosyl β-CD.39 N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAm) and azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA). Indomethacin (IND, ≥99%) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, USA) and used as received.

Synthesis of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm)

PNIPAm was synthesized by free radical polymerization of NIPAm (3.0 g) in methanol (20 ml) at 60˚C for 24 h using AIBN (0.3 g) and 2-mercaptoethanol (0.3 ml) as the initiator and chain-transfer reagent, respectively.27 The product was precipitated from ether after the reaction solution was concentrated, and then dried under vacuum with a yield of 76%. The average number molecular weight of PNIPAm was determined to be 1000 by MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy (Waters Micromass TofSpec-2E), which was run in linear mode. Dithranol (purchased from Aldrich Chemical) was used as a matrix, and tetrahydrofuran as a solvent for both the matrix and the polymer.

Synthesis of PEG-b-polyaspartamide containing EDA unit (PEG-b-PEDA)

The PEG-block-poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) (PEG-b-PBLA) copolymer was synthesized as reported by Harada et al.40 Briefly, BLA-NCA was polymerized in DMF at 40°C by the initiation of the terminal primary amino group of MPEG-NH2 to obtain PEG-b-PBLA. The degree of polymerization (DP) of PBLA was calculated to be 16 based on 1H NMR spectroscopy. PEG-b-PEDA was prepared through the quantitative aminolysis reaction of PEG-b-PBLA in dry DMF at 40°C in the presence of 50-fold molar of EDA.41 After 48 h, the reaction mixture was dialyzed against deionized water (MWCO: 3500), and the final aqueous solution was lyophilized to white powder.

Synthesis of PEG-b-PCD

β-CD containing copolymer PEG-b-PCD was synthesized by nucleophilic reaction.42 Briefly, lyophilized PEG-b-PEDA (600 mg) together with 5 fold excess amount of 6-monotosyl β-CD were reacted in 30 ml of anhydrous DMSO. After 5 days, the reaction mixture was dialyzed against 0.1 N NaOH for 2 days to remove any unreacted 6-monotosyl β-CD, and then dialyzed against distilled water for 2 days. After being filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter, the resultant aqueous solution was lyophilized to brown powder.

Preparation of host-guest assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD and PNIPAm

For the preparation of assemblies, both PEG-b-PCD and PNIPAm of various weight ratios were dissolved in water, the aqueous solution was then filtered through a 0.45 μm syringe filter. The filtrate was lyophilized.

Preparation and release study of indomethacin (IND) containing assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD and PNIPAm

To prepare drug containing assemblies, 10 mg IND was dissolved in 1.0 ml DMSO and added dropwise into an aqueous solution containing 20.0 mg PEG-b-PCD and 10 mg PNIPAm under sonication. The solution was then dialyzed against deionized water at 23°C for 24 h using dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 7-8 kDa. After filtering through a 0.8 μm syringe filter, the filtrate was lyophilized.

An in vitro drug release study was carried out at three different temperatures, i.e. 23, 31 and 37°C, to address the effect of temperature on the drug release profiles. Briefly, 3.0 mg lyophilized IND containing assemblies dispersed in 1.0 ml water was placed in a dialysis tubing (MWCO: 7-8 kDa), which was immersed into 30 ml PBS (pH 7.4, 0.01 M). At appropriate intervals, 4.0 ml was withdrawn from the outer aqueous solution, and replaced by a fresh PBS medium. The released IND was quantified spectrophotometrically at 280 nm.

Measurements

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian INOVA-400 spectrometer operating at 400 MHz. A turbidity experiment was performed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1601) equipped with a Peltier temperature controller (TCC-Controller, Shimadzu). The wavelength was kept at 500 nm. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements of the assemblies dispersed in aqueous solutions were performed with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument. An atomic force microscopy (AFM) observation was carried out on a NanoScope IIIa-Phase Atomic Force Microscope connected to a NanoScope IIIa Controller using an EV scanner. Samples were prepared by drop-casting the dilute solution onto freshly cleaved mica. All the images were acquired under a tapping mode. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation was carried out on a JEOL-3011 high resolution electron microscope operating at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. Samples were prepared at 25°C by dipping the grid into the aqueous solution of assemblies and the excess solution was blotted with filter paper. After the water was evaporated at room temperature for several days, samples were observed directly without any staining. Formvar coated copper grids, stabilized with evaporated carbon film, were used. SEM images were taken on a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (XL30 FEG, Phillips) after a gold layer was coated using a sputter coater (Desk-II, Denton vacuum Inc., Moorstown, NJ) for 80 s. Samples were prepared by coating aqueous solution of assemblies onto freshly cleaved mica, and water was evaporated at room temperature under normal pressure.

Results and discussion

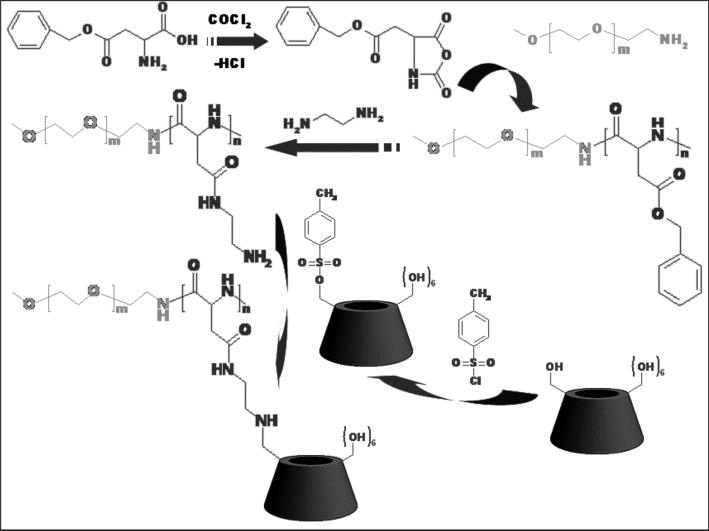

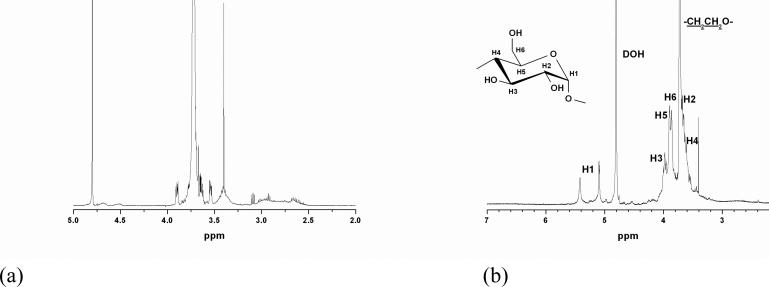

The synthesis route of double hydrophilic block copolymer with a PEG block and a β-CD containing block (PEG-b-PCD) is schematically illustrated in Scheme 1. To synthesize PEG-b-PCD, a copolymer with a PEG block and a polyaspartamide block containing ethylenediamine (EDA) unit (PEG-b-PEDA) was synthesized with the procedure established by Kataoka's group.43 α-Methoxy-ω-amino-PEG with an average Mw of 5000 was selected as another hydrophilic segment because it can provide the assemblies with good colloidal stability in vitro and in vivo. The 1H NMR spectrum of the synthesized PEG-b-PEDA is shown in Fig. 1a. The number of structural units containing the EDA group was calculated to be 16 according to the NMR result. Through a nucleophilic reaction between 6-monotosyl β-CD and the amino group of the PEG-b-PEDA, PEG-b-PCD was synthesized. 1H NMR spectrum and the corresponding assignments are shown in Fig. 1b, indicative of the successful synthesis of target block copolymer. Analysis of the 1H NMR spectrum reveals that approximately 13 β-CD molecules were introduced into the side chain of the PEDA segment. The resultant block copolymer could be easily dissolved in water at room temperature.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PEG-b-PCD.

Fig. 1.

1H NMR spectra of (a) PEG-b-PEDA, and (b) PEG-b-PCD in D2O at 25°C.

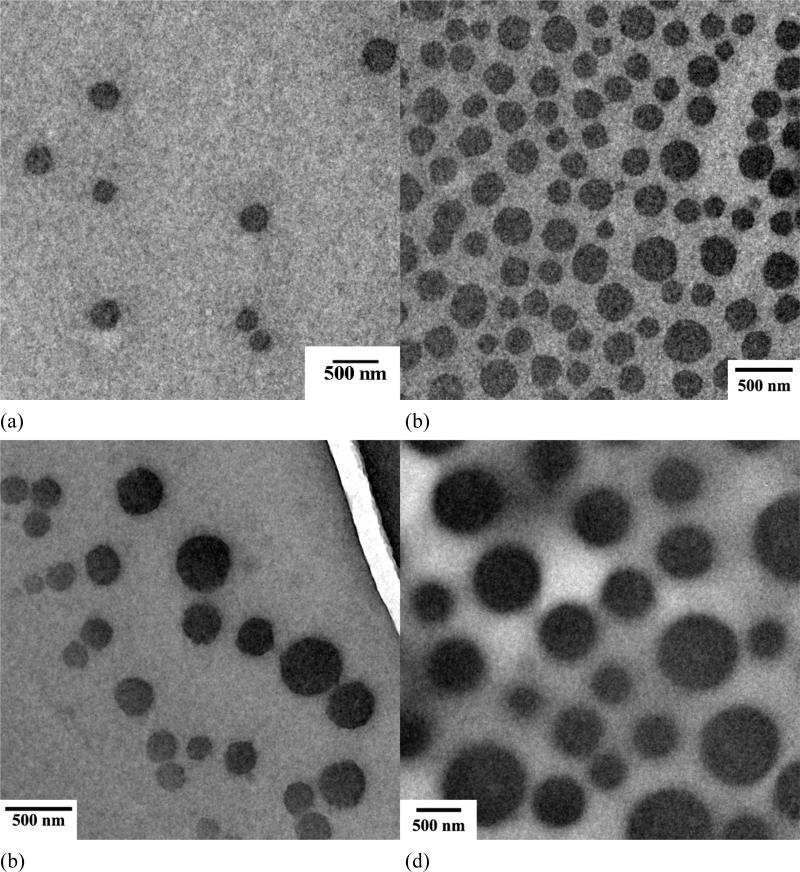

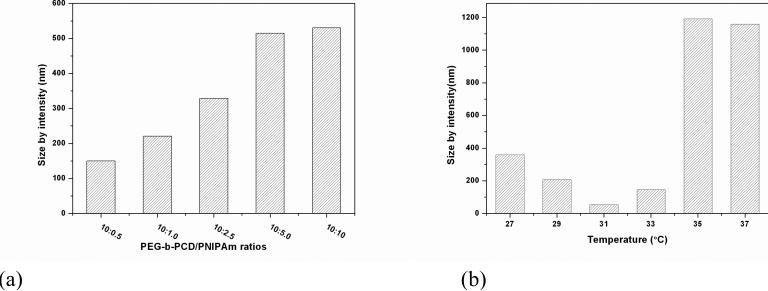

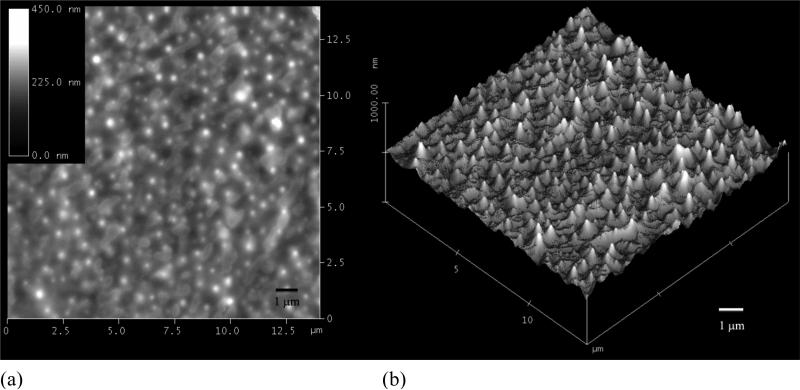

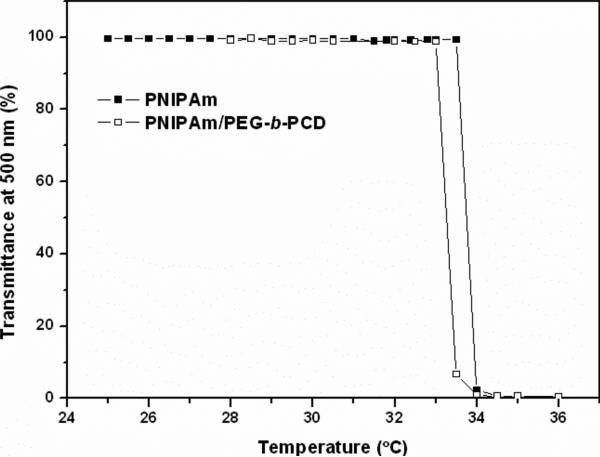

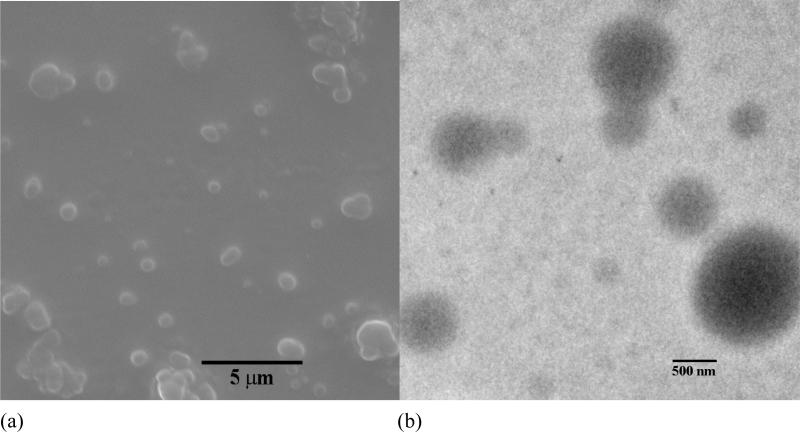

Polymeric assemblies based on PEG-b-PCD and PNIPAm were prepared by directly dissolving both polymers into an aqueous solution. Fig. 2 shows the TEM images of assemblies with various weight ratio of PNIPAm to PEG-b-PCD. Regardless of the content of PNIPAm in the assemblies, the morphology of these nanoparticles was observed to be essentially spherical (Fig. 2). TEM images shown in Fig.2 also suggested that the formed assemblies exhibited a relatively wide polydispersity. The average particle size of the assemblies increased with the PNIPAm content. The statistically number-averaged diameters from TEM images were 184, 250, 353, 536 and 560 nm for assemblies with the PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD ratios of 0.5:10, 1:10, 2.5:10, 5:10, and 10:10, respectively. The particle size of assemblies was also determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS). As shown in Fig. 3a, the mean size by intensity was 149, 221, 328, 515, and 530 nm, for assemblies based on 0.5:10, 1:10, 2.5:10, 5:10, and 10:10 of PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD ratio, respectively. This result was consistent with that from TEM observation, which gave slightly greater values than DLS. This discrepancy could be the result of a minor flattening effect when the TEM samples were dried on the grid. Assemblies with a PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD ratio of 2.5:10 were also observed using atomic force microscopy (AFM), and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM). As shown in Fig. 4a and 4b, spherical assemblies could also be observed. This coincides with the SEM image shown in Fig. 4c. The calculation based on several AFM images gives a number-average size of 435 nm, while SEM observation gives an average size of 455 nm. This increase in particle size when compared with DLS results also suggests the presence of a flattening effect. For both AFM and SEM experiments, assemblies were coated on mica surface, while Formvar coated copper grids, stabilized with evaporated carbon film, were used in TEM observation. Taken together, the TEM, AFM and SEM results indicate that the morphology of PEG-b-PCD based assemblies is spherical.

Fig. 2.

TEM images of assemblies based on PNIPAm and PEG-b-PCD of various weight ratios: (a) 0.5:10; (b) 1:10; (c) 2.5:10; (d) 5:10; (e) 10:10; (f) 2.5:10, loaded with IND.

Fig. 3.

(a) Average particle size of assemblies based on PNIPAm and PEG-b-PCD of various weight ratios, DLS measurement was performed at 25°C; (b) Temperature dependent particle size of assemblies with PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD ratio of 2.5:10.

Fig. 4.

Assemblies based on PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD with a weight ratio of 2.5:10, (a) High AFM image, (b) 3-D AFM image, and (c) SEM image.

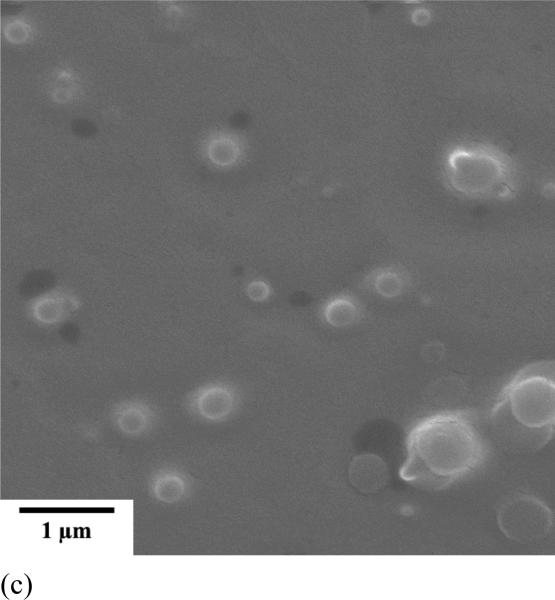

The formation of assemblies by PEG-b-PCD in the presence of PNIPAm suggests the existence of an inclusion interaction between β-CD and PNIPAm. We then conducted 1H NMR experiments and took a turbidity measurement. Fig. 5 shows the temperature dependent transmittance of PNIPAm aqueous solution with or without PEG-b-PCD.

Fig. 5.

Temperature dependent transmittance of PNIPAm alone and PNIPAm in the presence of PEG-b-PCD in aqueous solution. In both experiments, PNIPAm concentration was kept at 1.0 mg/ml, while the concentration of PEG-b-PCD was 3.0 mg/ml in PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD system.

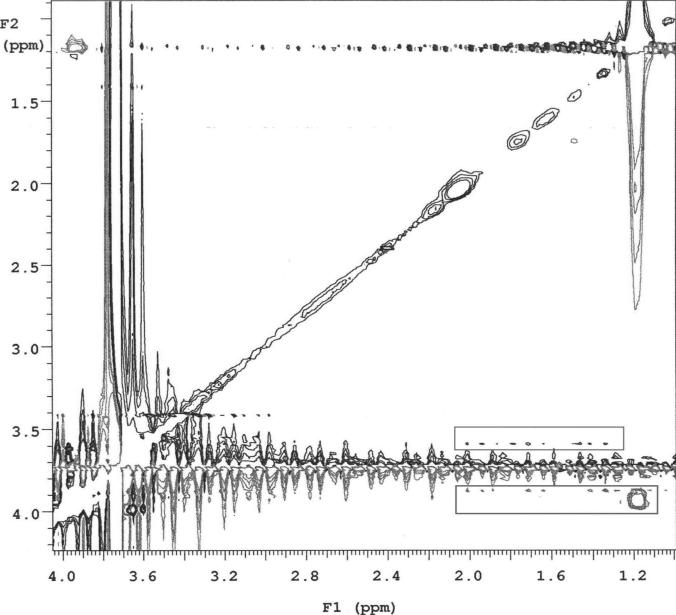

The lower critical solution temperature (LCST) was defined as the temperature where the transmittance decreased to 50%. LCST of a PNIPAm aqueous solution was found to be 33.8°C, while that in the presence of PEG-b-PCD was 33.3°C, suggesting a slight decrease. As reported by Wintgens et al, the LCST of PNIPAm copolymer with a hydrophobic segment decreased in the presence of cyclodextrin containing polymer, due to the inclusion complexation between CDs and hydrophobic groups of various polymer chains.44 This interaction might serve as a physical cross-linking, which leads to the formation of a pseudo-PNIPAm copolymer with high molecular weight. Compared with a low molecular weight polymer, PNIPAm with a high molecular weight exhibits a relatively low LCST.45 Accordingly, the decrease in LCST of PNIPAm in the presence of PEG-b-PCD implies that there is possible existence of inclusion complexation between PNIPAm and PEG-b-PCD. Further evidence can be found in the 2D ROESY NMR experiment, which has been widely adopted by many researchers to confirm the interaction between cyclodextrins and hydrophobic groups.32, 46 As illustrated in Fig. 6, the 2D ROESY spectrum indicates the interactions between β-CD rings and isopropyl groups of PNIPAm. The protons of isopropyl groups at about 1.2 ppm are directly correlated to the protons at δ=3.8-4.0 ppm. As observed from Fig. 1b, the protons with δ=3.8-4.0 ppm in β-CD correspond to H3 and H5 protons. These results demonstrate the formation of inclusion complexation between β-CD rings of PEG-b-PCD and isopropyl groups in PNIPAm. In addition, the association constant (Ka) between β-CD and isopropyl group is about 3.8 mmol/dm3 as determined spectrophotometrically by Matsui et al.47 Accordingly, the driving force for the formation of assemblies is inclusion interaction between PEG-b-PCD and PNIPAm.

Fig. 6.

2D Roesy NMR spectrum of PEG-b-PCD in the presence of PNIPAm.

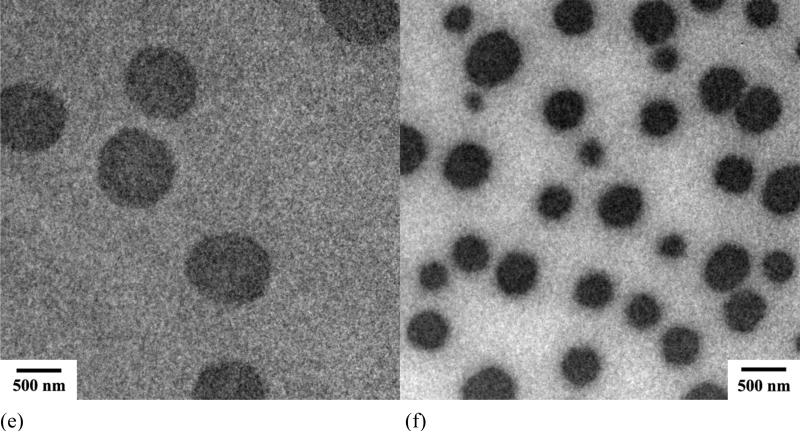

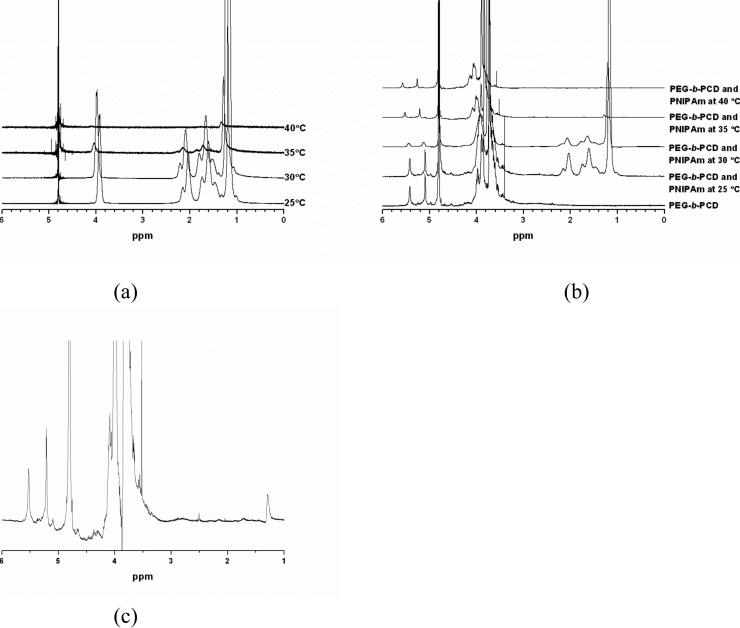

The thermosensitivity of assemblies formed by PEG-b-PCD in the presence of PNIPAm was investigated by temperature dependent DLS and NMR measurements. For assemblies based on the PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD ratio of 2.5:10, the mean particle size (by intensity) at temperatures ranging from 27 to 35°C was determined by DLS. From the result shown in Fig. 3b, one can observe the change of particle size with temperature. A dramatic decrease in mean particle size from 358 to 53 nm was observed as the temperature increased from 27 to 31°C. However, further temperature increase resulted in an increase in the average particle size. A relatively small increase from 53 to 146 nm was found with temperature increasing from 31 to 33°C, while a dramatic increase from 146 to 1191 nm was observed as temperature increased from 33 to 35°C. This temperature triggered size increase was further confirmed by SEM and TEM images show in Fig. 7. Such particle size increase likely resulted from the aggregation of many original assemblies. Further increasing temperature had no significant effect on the particle size. In addition, this process was completely reversible. The same phenomenon has been reported for amphiphilic graft copolymers containing PNIPAm.48 These changes in particle size should be attributed to the thermosensitivity of PNIPAm itself. As presented in Fig. 5, a significant transmittance change occurred at about 33.8°C for PNIPAm alone, while it took place around 33.3°C in the case of PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD system. Below the transition temperature, PNIPAm chains exhibited an extended conformation, and in this case the hydrogen bonding interaction between amide groups and water molecules dominates the hydrophobic interaction between isopropyl groups, which is the initial driving force for dissolution. However, above the transition temperature, the enhanced hydrophobic interactions between isopropyl groups likely lead to the collapse of PNIPAm chains.49 This temperature induced phase transition was also evidenced by 1H NMR measurements. Fig. 8a shows the 1H NMR spectra of PNIPAm at various temperatures. All the signals due to the protons of isopropyl, methylene and methane were observed from the spectrum at 25°C, while these signals were dramatically attenuated when the temperature was above 30°C. A similar temperature effect was found in the case of the PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD system (Fig. 8b). However, a comparison of the spectra at 35°C suggested that proton signals corresponding to PNIPAm seemed to be more severely suppressed with the temperature increase in the presence of PEG-b-PCD (Fig. 8a&c). This result is consistant with the turbidity measurement. In addition, as can be seen from Fig. 8b, the signals at δ=5.0-5.6 ppm, which are associated with protons in the β-CD ring, were also weakened as the temperature increased. This result leads to the conclusion that β-CD rings might also participate in the formation of cores of assemblies, which provides additional evidence about the interaction between the β-CD-containing block of the copolymer with PNIPAm.

Fig. 7.

(a) SEM and (b) TEM images of assemblies with PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD ratio of 2.5:10.

Fig. 8.

1H NMR spectra at various temperatures: (a) PNIPAm, (b) PNIPAm and PCD-b-PEG, 5:20. (c) Magnified spectrum of PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD at 35°C shown in (b). D2O was used as solvent.

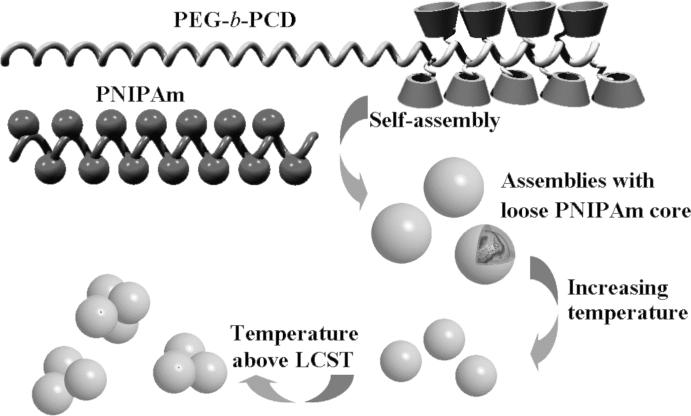

In summary, the above results have demonstrated the formation of assemblies by PNIPAm and a double hydrophilic copolymer with one block containing CDs. Inclusion complexation interaction between β-CD and isopropyl group of PNIPAm was found to be the driving force for this self-assembly process. Considering one CD unit can accommodate only one isopropyl group, a simple calculation suggested that isopropyl groups were excessive. Consequently, only a part of isopropyl groups participated in the host-guest interactions, while other isopropyl groups were still free enough to respond the temperature fluctuation. As a result, the presence of PNIPAm, a well studied thermosensitive polymer, endowed assembled nanoparticles with temperature responsive characteristics. An initial temperature increase resulted in a decrease in particle size. Further temperature increase to above the LCST of PNIPAm resulted in a particle size increase, which is likely due to an aggregation of the many individual particles. This process is illustrated in Scheme 2. However, these assemblies should exhibit loose cores. In this case, the β-CD containing block (PCD) functioned as a multi-covalent cross-linking component to hold PNIPAm chains together. Additionally, due to the highly hydrophilic nature of PEG, there should be a thinner shell mainly composed of PEG chains.

Scheme 2.

Assemblies constructed by PNIPAm and PEG-b-PCD.

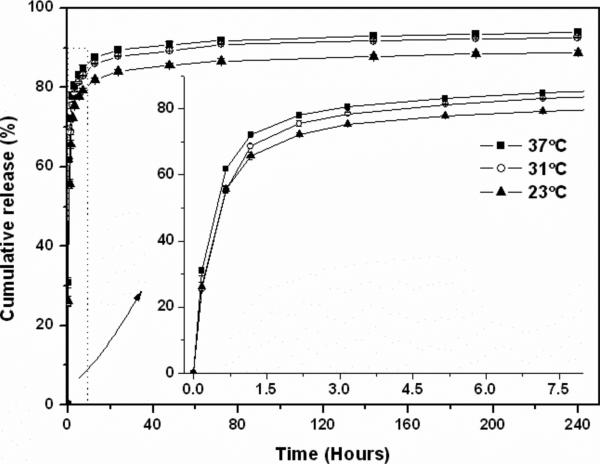

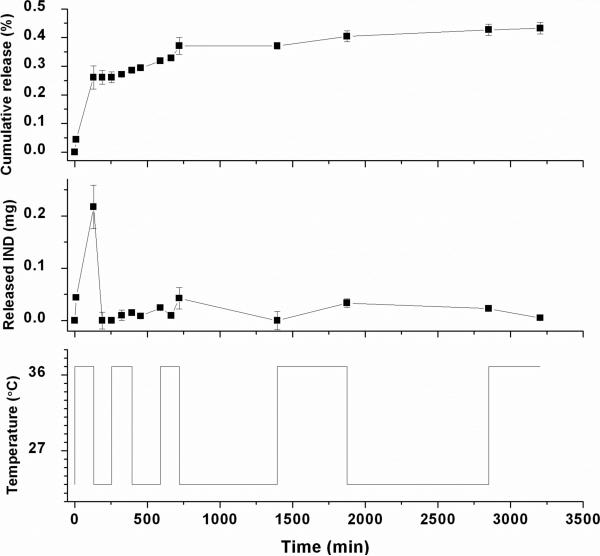

As studied by many groups, the thermosensitivity of assemblies can be adopted as an on/off switch to regulate the release profiles of payload both spatially and temporally.50-52 To demonstrate the possible application of assemblies based on PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD in the controlled drug delivery, encapsulation and release experiments were performed. Indomethacin (IND), a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, was selected as a model drug. IND-containing assemblies were prepared using the dialysis procedure. The mean size, determined by DLS was about 270 nm. The TEM image (Fig. 2f) shows that IND-loaded assemblies exhibit a spherical shape. This indicates that drug encapsulation did not significantly affect the morphology of assemblies. As quantified through UV measurement, a 21.2% IND load was achieved (encapsulation efficiency: 84.8%). To address the temperature effect, in vitro release tests were performed at three temperatures. Fig. 9 shows the in vitro release curves of IND-loaded assemblies. In general, a two-phase release profile was observed. After a rapid release within the first 12 h, a sustained release stage was observed. However, differences in the release profiles could be found at different temperatures. Within the first hour, the release rate at 37°C was significantly higher than that at 23 and 31°C. And then, the release rate at 31°C was accelerated, while the slowest release rate was observed at 23°C during the entire period studied. These temperature-dependent release profiles should be associated with the thermosensitivity of PNIPAm. For the release at 37°C (a temperature well above LCST of PNIPAm), the sudden temperature increase may cause the collapse of PNIPAm chains at first and then lead to the inter-particle aggregation as demonstrated by the DLS data. Whereas the former may accelerate the drug release (squeezing effect), the latter could slow down the drug diffusion. However, the data seems to suggest that this aggregation had a minor effect. The higher temperature might also have contributed to the increase of the diffusion rate. At 31°C, although PNIPAm chains may also shrink as shown in Fig. 3b, no aggregation took place in this case as this temperature is still below the LCST of PNIPAm. Although a slightly higher release rate was observed at 31°C, the commulative release at 31°C was still lower than that at 37°C. On the other hand, the PNIPAm chains assumed their extended conformation at 23°C. The drug molecules released by diffusion only from the assemblies. In this case, the driving force of drug release was concentration gradient only. A relatively slow release profile was therefore observed. Temperature induced rapid drug release has been also reported for polymeric assemblies based on amphiphilic copolymers containing PNIPAm segments.51, 52 Moreover, the IND release from PEG-b-PCD assemblies switched reversibly between on and off release states in response to temperature through the LCST (Fig. 10a). The release of IND was selectively accelerated upon heating through the LCST, while it was decelerated to a certain degree at a temperature below the LCST. Corresponding to this, the IND release rate changed upon temperature switching between 23 and 37°C (Fig. 10b). Although similar release profiles have been reported for polymeric micelles with PNIPAm as shells,52-54 the current study demonstrated that temperature modulated release profile can also be achieved through assemblies with PNIPAm chains as cores. These results substantiate the possible application of assemblies based on PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD in the field of controlled drug delivery.

Fig. 9.

In vitro release profiles of IND from assemblies based on PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD with a weight ratio of 5:10. IND loading was 21.2 wt%. Note: the error bars are smaller than the data point symbols.

Fig. 10.

In vitro release profiles of IND from PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD (5:10) assemblies in response to temperature switching between 23 and 37°C. IND loading was 9.3wt%.

Conclusions

A double hydrophilic block copolymer with a PEG block and a β-cyclodextrin-containing block (PEG-b-PCD), was synthesized. Nanoparticles were assembled from the PEG-b-PCD copolymer and PNIPAm. The driving force for the formation of these nano-sized assemblies was found to be inclusion complexation interaction between the hydrophobic cavity of β-cyclodextrin and isopropyl group of PNIPAm. The particle size of assemblies derived from PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD changed in response to the external temperature change. The particle size of the thermosensitive assemblies was also dependent on the weight ratio of PNIPAm/PEG-b-PCD. The particle size increased with the PNIPAm content. High loading efficiency of a model hydrophobic drug was demonstrated using these temperature-responsive assemblies. The subsequent release study showed that the payload could be released in a sustained manner, and the release rate could be modulated by temperature. A more rapid release rate was observed at higher temperatures, while a slower release rate was found at temperatures well below the LCST. These results demonstrate that such nanoparticles have high potential for controlled drug delivery applications when temperature responsiveness is desired.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the NIH (NIDCR DE015384 & DE017689, NIGMS GM075840).

References

- 1.Rapoport N. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007;32:962. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Discher DE, Ortiz V, Srinivas G, Klein ML, Kim Y, Christian D, Cai S, Photos P, Ahmed F. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007;32:838. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bose PP, Das AK, Hegde RP, Shamala N, Banerjee A. Chem. Mater. 2007;19:6150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torchilin VP. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:145. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sukhishvili SA. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;10:37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jun YJ, Toti US, Kim HY, Yu JY, Jeong B, Jun MJ, Sohn YS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:6173. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung JE, Yokoyama M, Aoyagi T, Sakurai Y, Okano T. J. Control. Release. 1998;53:119. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(97)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae Y, Fukushima S, Harada A, Kataoka K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:4640. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee ES, Kim D, Youn YS, Oh KT, Bae YH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:2418. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HI, Wu W, Oh JK, Mueller L, Sherwood G, Peteanu L, Kowalewski T, Matyjaszewski K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2453. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin AP, Mynar JL, Ma Y, Fleming GR, Frechet JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9952. doi: 10.1021/ja0523035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowik DWPM, Shklyarevskiy IO, Ruizendaal L, Christianen PCM, Maan JC, van Hest JCM. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:1191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reches M, Gazit E. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2006;1:195. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husseini GA, d. l. R. M.A.D., Gabuji T, Zeng Y, Christensen DA, Pitt WG. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007;7:1028. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin HY, Thomas JL. Langmuir. 2004;20:6100. doi: 10.1021/la049866z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oishi M, Nagasaki Y, Itaka K, Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1624. doi: 10.1021/ja044941d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katayama Y, Sonoda T, Maeda M. Macromolecules. 2001;34:8569. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV, Alakhov VY. J. Control. Release. 2002;82:189. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Hernandez J, Checot F, Gnanou Y, Lecommandoux S. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2005;30:691. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishiyama N, Kataoka K. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2006;193:67. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YY, Cheng H, Zhang ZG, Wang C, Zhu JL, Liang Y, Zhang KL, Cheng SX, Zhang XZ, Zhuo RX. ACS Nano. 2008;2:125. doi: 10.1021/nn700145v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang RX, Li XJ, Qiu LY, Li XH, Yan MY, Jin Y, Zhu KJ. J. Control. Release. 2006;116:322. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han HD, Choi MS, Hwang T, Song CK, Seong H, Kim TW, Choi HS, Shin BC. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;95:1909. doi: 10.1002/jps.20646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arotçaréna M, Heise B, Ishaya S, Laschewsky A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3787. doi: 10.1021/ja012167d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurisawa M, Yokoyama M, Okano T. J. Control. Release. 2000;69:127. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han HD, Shin BC, Choi HS. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2006;62:110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang JX, Qiu LY, Li XD, Jin Y, Zhu KJ. Small. 2007;3:2081. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rzaev ZMO, Dinçer S, Pişkin E. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007;32:534. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimitrov I, Trzebicka B, Muller AHE, Dworak A, Tsvetanov CB. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007;32:1275. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis ME, Brewster ME. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:1023. doi: 10.1038/nrd1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang YP, Ma N, Wang ZQ, Zhang X. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2823. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng W, Yamaguchi H, Takashima Y, Harada A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5144. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kretschmann O, Choi SW, Miyauchi M, Tomatsu I, Harada A, Ritter H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4361. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Yang C, Li HZ, Wang X, Goh SH, Ding JL, Yang DY, Leong KW. Adv. Mater. 2006;18:2969. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ooya T, Choi HS, Yamashita A, Yui N, Sugaya Y, Kano A, Maruyama A, Akita H, Ito R, Kogure K, Harashima H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3852. doi: 10.1021/ja055868+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Jiang M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3703. doi: 10.1021/ja056775v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tellini VHS, Jover A, Garcia JC, Galantini L, Meijide F, Tato JV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5728. doi: 10.1021/ja0572809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daly WH, Pochė D. Tetrahedron lett. 1988;29:5859. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baussanne I, Benito JM, Mellet CO, Fernández JMG, Law H, Defaye J. Chem. Commun. 2000:1489. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harada A, Kataoka K. Macromolecules. 1995;28:5294. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnida N. Nishiyama, Kanayama N, Jang WD, Yamasaki Y, Kataoka K. J. Control. Release. 2006;115:208. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang JX, Ma PX. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:964. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanayama N, Fukushima S, Nishiyama N, Itaka K, Jang WD, Miyata K, Yamasaki Y, Chung UI, Kataoka K. ChemMedChem. 2006;1:439. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wintgens V, Charles M, Allouache F, Amiel C. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2005;206:1853. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schild HG, Tirrell DA. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:4352. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitz S, Ritter H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5658. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsui Y, Mochida K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979;52:2808. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang JX, Qiu LY, Zhu KJ, Jin Y. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2004;25:1563. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schild HG. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1992;17:163. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang JX, Yan MQ, Li XH, Qiu LY, Li XD, Li XJ, Jin Y, Zhu KJ. Pharm. Res. 2007;24:1944. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li YY, Zhang XZ, Kim GC, Cheng H, Cheng SX, Zhuo RX. Small. 2006;2:917. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chung JE, Yokoyama M, Yamato M, Aoyagi T, Sakurai Y, Okano T. J. Control. Release. 1999;62:115. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei H, Zhang XZ, Zhou Y, Cheng SX, Zhuo RX. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2028. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung JE, Yokoyama M, Okano T. J. Control. Release. 2000;65:93. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00242-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]