Abstract

We used event-related potentials (ERPs) to examine the time-course of processing metaphorical and literal sentences in the brain. ERPs were measured to sentence-final (Experiment 1) and mid-sentence (Experiment 2) critical words (CWs) as participants read and made plausibility judgments about familiar nominal metaphors (“A is a B”) as well as literal and semantically anomalous sentences of the same form. Unlike the anomalous words, which evoked a robust N400 effect (on the CW in experiments 1 and 2 as well as on the sentence-final word in experiment 2), CWs in the metaphorical, relative to the literal, sentences only evoked an early, localized N400 effect that was over by 400 ms after CW onset, suggesting that, by this time, their metaphorical meaning had been accessed. CWs in the metaphorical sentences also evoked a significantly larger LPC (Late Positive Component) than in the literal sentences. We suggest that this LPC reflected additional analysis that resolved a conflict between the implausibility of the literal sentence interpretation and the match between the metaphorical meaning of the CW, the context and stored information within semantic memory, resulting from early access to both literal and figurative meanings of the CWs.

Keywords: language, semantic, metaphor, ERP, N400, LPC, P600

Introduction

Metaphors are pervasive in everyday language (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). They are often used to describe abstract concepts and ideas in a more concrete and vivid way than can be expressed using literal language. For example, in the sentence, “Unemployment is a plague”, “plague” is used to describe the abstract or general phenomenon of “things that are unpleasant or likely to cause damage” by likening it to the more concrete concept of disease. The pervasiveness of metaphors, however, does not mean that their processing is straightforward. This is because of their inherently paradoxical nature: they establish a figurative meaning by positing a relation of equality between two relatively dissimilar entities, either explicitly, as in nominal metaphors (metaphors of the type “A is a B”, e.g. “That guy is a pig”) or implicitly, as in qualifying metaphors (in which the metaphor is expressed through an adjective or an adverb, e.g. “He was boiling mad”). This means that, if interpreted literally, such sentences do not make sense. The conflict between the literal and the figurative meaning of metaphors poses a challenge to the language comprehension system. This study used event-related potentials (ERPs) to shed light on how this challenge is met at a neural level during word-by-word comprehension of familiar nominal metaphors.

A variety of neurocognitive models have been proposed to describe the processing of metaphors. The original standard pragmatic or hierarchical model (Grice 1975; Searle 1979) makes two claims: first, that processing is serial, such that the literal meaning of a metaphorical sentence (for example, “Unemployment is a plague” meaning “Unemployment is an epidemic disease with high mortality”) is first computed; this literal meaning is perceived as ill-formed, and this leads to a search for the metaphorical meaning of the utterance (henceforth referred to as the ‘serial processing claim’). Second, this model views metaphors as deviations from normal language, and therefore assumes that metaphor comprehension requires mechanisms that are qualitatively different from those used for literal sentence processing (henceforth referred to as the ‘specialness claim’).

At the other end of the continuum, the direct access model (Gibbs & Gerrig 1989; Gibbs 2002) holds that the metaphorical meaning of a sentence (e.g. “Unemployment is a plague” meaning “Unemployment is unpleasant or likely to cause damage”) is directly accessed, without the literal meaning of the whole sentence being constructed first or in parallel, so long as the context supports the metaphorical meaning.

While the direct access model assumes that context is the key factor which determines whether a comprehender will immediately compute the metaphorical or the literal meaning of a sentence, other theories postulate that context is just one of many factors that determine which meaning will be accessed. This becomes clear in Giora's (1997) graded salience model, which considers the semantic ‘salience’ of a particular word critical to determining which meaning will be initially accessed. For example, if the metaphorical usage of a particular word is common, prototypical and conventional (e.g. “plague” commonly used to mean “things that are unpleasant or likely to cause damage”), then, in addition to its literal meaning, its metaphorical meaning is said to be salient and therefore initially accessed, even when it is encountered in a context which does not pave the way towards its metaphorical interpretation. This predicts parallel access of both the literal and the metaphorical meanings of critical words in familiar metaphors. If, on the other hand, a word is unfamiliar or not often used metaphorically, its metaphorical meaning is said to be non-salient, and its literal meaning is initially accessed, even if it is embedded in a context that biases towards its metaphorical interpretation. At a later stage of processing, the activated meanings are either retained or suppressed depending on whether or not they aid the construction of the relevant meaning.

The results of most behavioral studies have suggested that literal and, at least, familiar metaphorical sentences are equally easy to comprehend (e.g. McElree & Nordlie 1999; see Glucksberg 2003 for an overview). This has often been taken as evidence against serial (as well as specialness) aspects of the hierarchical model (see Hoffman & Kemper 1987 for a discussion of the difficulties in interpreting behavioral results to support the hierarchical model). Moreover, when participants are asked to judge the literal plausibility of sentences, they take longer to make their judgments to metaphorical than to anomalous sentences. This has been interpreted as evidence for the direct access of metaphorical meaning, which interferes with such literal plausibility judgments (e.g. Glucksberg, Gildea & Bookin 1982; Faust & Weisper 2000). In addition, distinct processing patterns have been observed to familiar and unfamiliar metaphors, supporting the graded salience model (for a review, see Giora 2002). However, many of these studies measured decision times (in which whole sentence comprehension and decision processes are conflated, e.g. Glucksberg et al. 1982, Blasko & Connine 1993) or whole-sentence reading times (e.g. Giora & Fein 1999, but see Brisard, Frisson & Sandra, 2001; Janus & Bever, 1985; Rubio Fernández, 2007). ERPs allow for an online assessment of neural activity with millisecond (ms) temporal resolution, allowing for an analysis of when distinct neurocognitive processes come into play during metaphor comprehension.

The two ERP components of particular relevance to the present study are the N400 and the Late Positive Component (LPC). The N400 is a waveform with negative polarity and a peak at around 400 ms after stimulus onset. The amplitude of this waveform is larger (more negative) to words that are semantically unassociated (versus associated) with preceding single words (Rugg 1984; Bentin et al. 1984), and that are incongruous (versus congruous) or unpredictable (versus predictable) with respect to their preceding sentence contexts (Kutas & Hillyard 1980, 1984), global discourse contexts (Van Berkum, Hagoort & Brown 1999) and our knowledge of what we know to be true or likely in the world (Kuperberg et al. 2003a, b; Hagoort et al. 2004). Its modulation is thought to reflect the ease of mapping the meaning(s) of incoming words onto semantic memory structure and sentence and discourse level context (Federmeier & Kutas 1999; Kutas & Federmeier 2000; Kutas et al. 2006; Federmeier et al. 2007; Lau et al. 2008; Van Berkum (2009); Van Petten & Kutas 1990; Van Berkum et al. 1999).

There is less consensus on the functional relevance of the LPC that is sometimes evoked in addition to the N400 during online language comprehension. The LPC refers to a group of positive-going components that peak later than the N400 and that can extend until approximately 900 ms after word onset. An anterior LPC is seen to plausible but unpredictable words within highly constraining contexts (Federmeier et al. 2007). A posterior LPC has been seen extensively in association with words that violate the syntactic structure of their preceding context (Hagoort et al. 1993; Osterhout & Holcomb 1992), where it has been termed the P600. An LPC/P600 has also been observed, under some circumstances, to certain types of semantic verb-argument violations/implausibilities (Kuperberg et al. 2003b, 2006a, 2006b, 2007a, 2007b; Kim & Osterhout 2005; Kolk et al. 2003; Hoeks et al. 2004), and severe semantic implausibilities outside the verb-argument structure (Van de Meerendonk et al. 2010). The LPC/P600 is thought to reflect a continued analysis (or reanalysis), either at the linguistic level of input that produced the violation (Kuperberg 2007a), or a complete reanalysis of the input (Kolk & Chwilla 2007; Van de Meerendonk et al. 2009, 2010)1. Interestingly, its amplitude is modulated by whether the semantic context is constraining for an alternative interpretation, i.e. when the system reaches conflicting conclusions as to whether the sentence makes sense or not. With respect to the P600 evoked by semantic implausibilities, there is increasing recognition that there is no single trigger for this effect, rather it is triggered by a set of factors: the degree of implausibility of the critical word, the degree of contextual constraint for an alternative interpretation, the task performed by the comprehender (plausibility judgment or passive comprehension) and individual differences in working memory capacity (Kuperberg 2007). None of these factors is necessary or sufficient for evoking a P600 effect; rather, they appear to act in consort such that this effect is produced only past a particular threshold. Although there is debate as to the functional relevance of this effect, there is a general consensus that the function of such additional analysis serves the purpose of ensuring that the comprehender reaches an accurate final interpretation of the input (see Kuperberg 2007a; Van de Meerendonk et al. 2009).

There have been several ERP studies examining the N400 and LPC components in relation to metaphor comprehension. Pynte, Besson, Robichon & Poli (1996) measured ERPs on the sentence-final words of familiar metaphorical sentences (e.g. “Those fighters are lions”) and literal sentences (e.g. “Those animals are lions”). The metaphorical sentence-endings evoked a larger-amplitude N400 than the literal sentence endings, suggesting that they were more difficult to process semantically. However, the absence of a larger LPC on final words of the metaphorical (versus literal) sentences was interpreted as evidence against the serial processing claim of the hierarchical model, which would have predicted a need for reanalysis as readers first rejected the literal meaning of the sentence-final word and subsequently constructed the metaphorical meaning of the sentence.

Coulson & Van Petten (2002) expanded on Pynte et al.'s (1996) study. Again, participants read sentences ending with words that, depending on the context, could be interpreted literally or metaphorically (e.g. literal: “That stone we saw in the natural history museum is a gem.”; metaphorical: “After giving it some thought, I realized the new idea was a gem.”). In an intermediate condition (the literal mapping condition) these words were used literally but in a rather unusual situation (e.g. “The ring was made of tin, with a pebble instead of a gem.”). Again, a larger N400 was evoked by the CWs within the metaphorical relative to the literal sentences. In contrast to Pynte et al. (1996), however, the metaphorically-interpreted words also evoked a posterior LPC effect, relative to the literally-interpreted words. Coulson & Van Petten (2002) suggested that CWs in the metaphorical sentences were perceived as incongruous with their context, leading to an N400 effect, and that this was followed by a search for additional material from semantic memory, and possibly a reanalysis, reflected by the LPC, to establish congruence between the context and the metaphorical meaning of the CW. CWs in the literal mapping condition evoked an N400 and an LPC intermediate in amplitude between the literal and metaphorical condition. The authors therefore argued against the idea that metaphorical language is processed with different mechanisms than literal language, and claimed that literal mapping and metaphors increasingly tax the same language processing mechanisms that are used for literal language processing (see also Kutas et al. 2006). However, their interpretation is consistent with serial processing aspects of the hierarchical model and of the graded salience model for novel metaphors, i.e. that the metaphorical meaning of the CW was only accessed after its literal meaning was perceived as incongruous with the context.

The N400 results were replicated by Coulson & Van Petten (2007) in a study that combined the divided visual field method with ERP measurement. In this study, metaphorical CWs (e.g. “orgy” in “Unfortunately, what started as mere flirtation with the stock market has become an orgy.”), elicited a more negative N400 than literal CWs that were matched in low cloze probability (e.g. “orgy” in “They ended the year with a huge party that everyone remembered as the orgy.”), regardless of whether they were presented to either the right or the left hemisphere. As in their previous study, this N400 effect was interpreted as reflecting the increased difficulty in semantically integrating the metaphorically- relative to the literally-interpreted CWs. However, unlike their previous study, the metaphorical CWs evoked a less positive LPC than the literal CWs (this positivity was broadly distributed across the scalp when CWs were presented to the right hemisphere, and had a left-anterior focus when CWs were presented to the left hemisphere). The larger LPC to the literal (relative to the metaphorical) CWs is inconsistent with serial processing, which would predict an additional search to retrieve metaphorical meaning; indeed, the authors suggested that such increased reanalysis was engaged to the literal CWs, perhaps because the literal contexts were of higher semantic constraint than the metaphorical contexts (see Federmeier et al. 2007).

In line with Coulson & Van Petten's (2002, 2007) findings, Lai et al. (2009) found N400 effects to both conventional and novel metaphorical sentence-final CWs compared to literal CWs, with a longer-lasting effect to novel metaphorical CWs. However, the degree to which these findings were driven by differences in mean sensicality ratings across the three conditions is unclear.

Support for a form of the direct access model was found in a study by Iakimova et al. (2005), who measured ERPs to CWs in literal, metaphorical and semantically anomalous sentences as participants judged their plausibility. The semantically anomalous words evoked both an N400 and an LPC effect (relative to CWs in both other sentence types). Neither the N400 nor the LPC, however, were larger to the metaphorical than to the literal words, leading the authors to conclude that the metaphorical meaning was accessed immediately during metaphorical sentence processing2.

Finally, two ERP studies lend some support to Giora's (1997) graded salience hypothesis. The first examined idioms (Laurent et al. 2006). Idioms, like familiar metaphors, have non-literal meanings which, according to Giora & Fein (1999), are at least as salient as their literal meanings; but, unlike most metaphors, idioms have been used so commonly in language that the entire multi-word expression has become syntactically fixed and may be stored as such in the lexicon (Jackendoff 1997). Participants read weakly salient idioms (e.g. “enfoncer le clou”; “to hammer it home”) and strongly salient idioms (e.g. “rendre les armes”; “to surrender weapons”), each with different CWs, and then made lexical decisions to target words that were semantically related to either the literal or non-literal meanings of the idioms. The CW of weakly salient idioms evoked both a larger N400 and LPC than the CW of strongly salient idioms, perhaps reflecting initial semantic integration difficulty and additional analysis, as discussed above. Moreover, after strongly salient, but not weakly salient idioms, target words that were semantically related to the idioms' figurative meanings evoked a smaller N400 amplitude than target words related to their literal meanings. This suggested that, during the processing of strongly salient idioms, only idiomatic meanings were active at a later stage of processing.

A second ERP study by Arzouan, Goldstein & Faust (2007) that could be argued to support the graded salience hypothesis reported a larger N400 to novel metaphoric word pairs, relative to both literal and conventional metaphoric word pairs, which did not differ from each other. This N400 effect, reflecting initial semantic difficulty, was followed by a late negativity to novel metaphoric word pairs, which was argued to reflect secondary semantic integration processes. These results were interpreted as supporting sequential processing for novel, but not conventional, metaphors.

In sum, there are conflicting findings from existing ERP studies of metaphor and idiom comprehension, and all models of processing – serial aspects of the hierarchical model, direct access and graded salience – receive some support. There are many reasons – some methodological and some theoretical – for these conflicting findings. For example, in some studies, different CWs, which may have differed in frequency, concreteness and imageability, were used across conditions (e.g. Laurent et al. 2006; Tartter et al. 2002). In most previous studies, it is unclear whether syntactic/thematic structure or complexity were matched across the literal and metaphorical sentences (Coulson & Van Petten 2002, 2007; Iakimova et al. 2005; Laurent et al. 2006) – two factors known to affect the modulation of the LPC (e.g. Kuperberg 2007a; Kaan & Swaab 2003; Friederici, Hahne & Saddy 2004). Different studies employed different tasks such as plausibility judgments (Iakimova et al. 2005; Arzouan et al. 2007), sensicality ratings (Lai et al. 2009), lexical decisions (Laurent et al. 2006), reading for comprehension (Pynte et al. 1996) and answering comprehension questions (Coulson & Van Petten 2002, 2007), all also known to affect the modulation of these ERP components. Individual differences between participants may also explain some of the variation in ERP results (Kazmerski et al. 2003). Finally, different studies may have used metaphors with different degrees of familiarity, and sometimes more than one type of metaphor was used in the same study, for example nominal and predicative and/or implicit metaphors (Tartter et al. 2002; Iakimova et al. 2005; Lai et al. 2009), which may be processed in different ways (Giora 2002; Schmidt et al. 2007; Arzouan et al. 2007; Schmidt et al. 2009).

The current study used ERPs to study the time course of processing a single type of familiar metaphor while keeping constant as many confounding variables as possible. We examined familiar, nominal metaphors that take the form “A is a B” (e.g. “Unemployment is a plague”). These were compared with literal sentences (e.g. “Cholera is a plague”) that were matched in cloze probability and with semantically anomalous sentences (e.g. “Metal is a plague”). All three sentences had exactly the same structure and number of words and the same CWs were fully counterbalanced across the three sentence types. Two experiments were conducted: one in which the CW (e.g. “plague”) was also the sentence-final word, as in the examples above, and one in which the CW was followed by several other words before the end of the sentence (e.g. “Unemployment is a plague that affects many people.”). The first experiment allowed us to examine the neural basis of metaphor comprehension at the point of sentence wrap-up, where final integration of the overall meaning of a sentence takes place. This also allowed us to compare our findings with those of previous studies, where the CW was usually the sentence-final word. The second experiment allowed us to examine the processing of CWs in the absence of any sentence-final wrap-up effects, as well as to determine whether any neural effects of metaphor processing continued after the CW, as the meaning of the sentence further unfolded.

Experiment 1

Introduction

In this experiment, we measured the amplitude of the N400 and the LPC time-locked to the onset of the CW, which was also the sentence-final word. Three sentence types were compared: literal, familiar metaphorical, and semantically anomalous (Table 1, left), and participants were asked to judge sentence plausibility at the end of each sentence. The preceding sentence context biased the interpretation of the CW as literal, metaphorical or anomalous.

Table 1.

Examples of the three sentence types in Experiments 1 and 2

| Sentence Type | Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Literal | ||

| The first NP is chosen such that the second NP is interpreted literally. | Cholera is a plague. | Cholera is a plague that affects many people. |

| Metaphorical | ||

| The first NP is replaced by an NP that elicits a metaphorical interpretation of the critical word. | Unemployment is a plague. | Unemployment is a plague that affects many people. |

| Anomalous | ||

| The first NP is replaced by an NP that renders the critical word semantically anomalous. | Metal is a plague. | Metal is a plague that affects many people. |

In the examples, the critical word is underlined.

Based on our knowledge about the neurocognitive processes indexed by the N400 and LPC, it is possible to make predictions about which of these components may be evoked by CWs in these familiar metaphors, relative to both the literal and anomalous sentences, particularly with regard to a serial model versus the graded salience hypothesis3.

A fully serial model of metaphorical processing, in which the literal meaning of a CW is accessed before its metaphorical meaning (regardless of whether it is familiar or unfamiliar), might predict an N400 to the metaphorical CW that is just as large as to the clearly anomalous word, because the literal meaning, like the meaning of the anomalous word, would be initially perceived as incongruous with the context, leading to initial difficulties in semantic mapping. A serial model would, in addition, predict an LPC effect to the CW in the metaphorical sentences, reflecting the additional processing or reanalysis required to access the metaphorical meaning and integrate it with the context.

The graded salience hypothesis would predict no N400 effect to familiar metaphorical (relative to the literal) CWs, as the metaphorical meaning of the CWs is claimed to be activated immediately for such familiar metaphors. However, we suggest that such a model could be reconciled with an LPC effect. In familiar metaphors, the literal meaning of the CW would also be accessed and could be temporarily retained. This activation of the literal (in addition to the metaphorical) meaning of the CW could lead to an implausible literal sentence interpretation which would conflict with a plausible metaphorical sentence interpretation. This conflict could trigger a continued analysis (or reanalysis) of the sentence meaning (Kuperberg 2007a; Van de Meerendonk et al. 2009).

Methods

Development and Pre-testing of Materials

One hundred and fourteen sentence triplets were initially constructed. All sentences took the form, “NP is/was a(n) CW”. Each CW was used in a literal sentence, a metaphorical sentence (a familiar nominative metaphor) and a semantically anomalous sentence (Table 1; see www.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/kuperberglab/materials.htm for additional examples). The only content word that differed across the three sentence types was the first NP. This ensured that the number of words per sentence and the syntactic structure were identical across the three sentence types.

Cloze Probability and Contextual Constraint

Sentences up until, but not including, the CW were presented on a computer to 24 undergraduate students at Tufts University who did not participate in the ERP study and who gave written, informed consent before participation. Participants were asked to type in a word that could plausibly complete the sentence. Cloze probabilities were calculated and sentences were eliminated, rewritten and re-clozed in 8 more individuals until the average cloze probabilities of the CWs in the literal and figurative sentences were matched. Final cloze probabilities of all three sentence types used in the ERP experiment are given in Table 2. The average cloze probability of CWs in the literal and metaphorical sentences were both low and did not differ significantly from one another on either a subjects analysis, t1(31) = 0.96, p = 0.34, or an items analysis, t2(184) = 1.09, p = 0.28. As expected, the cloze probability in the anomalous sentences was zero and differed significantly from the literal and metaphorical sentences on both subjects and items analyses (all ts > 3.12, all ps < 0.01). After the cloze ratings, 93 sentence triplets remained.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the three sentence types

| Sentence Type | Cloze probability | Familiarity | Figurativeness | Sentence plausibility (Experiment 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Literal | 0.03 (0.03) |

3.34 (0.76) |

1.12 (0.16) |

4.30 (0.44) |

| (2) Metaphorical | 0.02 (0.03) |

3.54 (0.71) |

2.04 (0.11) |

4.24 (0.58) |

| (3) Anomalous | 0.00 (0.00) |

NA | NA | 1.52 (0.37) |

Means are shown with standard deviations in brackets. NA: Not applicable.

The rating scores are based on the 93 sentence triplets selected for the ERP experiments

The cloze data were also used to calculate the semantic constraint of our sentences. For this, we used the percentage of the most frequently occurring response to each sentence stem in the cloze test. On average, the semantic constraint of the literal sentence stems was greater (31%) than that of the metaphorical sentence stems (23%), p < .001.

Familiarity

We conducted a norming study to assess the familiarity of the selected 93 literal and 93 metaphorical sentence types. Participants in this rating study were undergraduate students who did not participate in either ERP study or any other norming study, and who gave written, informed consent before participation.

In this norming study, the literal and metaphorical sentence types were counterbalanced across four lists, each presented in pseudo-random order to 40 participants in total. We also included the 31 metaphorical filler sentences of our main experiment (see below), 23 familiar metaphors from other studies (12 from Blasko & Connine 1993, 11 from Katz et al. 1988), and 144 unfamiliar metaphors from other studies (24 from Blasko & Connine 1993, 90 from Katz et al. 1988, 20 from Bottini et al. 1994 and 10 from Tartter et al. 2002). Each list contained 60 ‘familiar’ sentences (from the first four categories mentioned above), and 60 unfamiliar metaphorical sentences (some of the unfamiliar metaphorical sentences were used in more than one list). All participants were asked to judge the familiarity of each sentence on a scale from 1 (low familiar) to 5 (high familiar).

Five participants were excluded because they demonstrated insufficient knowledge of metaphors: more than 65% of their responses were in category 1 and less than 10% of their responses were in category 4 and 5 combined. Mean ratings for each sentence type are reported in Table 2. The subjects analysis revealed no significant difference in familiarity between our literal and metaphorical experimental sentences (t < |-1.57|, p > .10), while the items analysis indicated that the literal sentences were rated as slightly less familiar than the metaphorical sentences (t > |-1.99|, p < .05). Both our literal and metaphorical experimental sentences were rated as being equally familiar as the familiar metaphorical sentences used by Katz et al.'s (1988) and Blasko & Connine's (1993) (ts < .76, ps > .45 if compared with our literal sentences; ts > 1.68, ps < .10 if compared with our metaphorical sentences). Indeed, there was a trend for our metaphorical sentences to be rated as more familiar than the familiar metaphorical sentences from these other studies (mean rating of the former: 3.54; mean rating of the latter: 3.23). Our metaphorical experimental sentences were rated as significantly more familiar than the unfamiliar metaphors from the other studies (mean rating of the latter: 1.58; ts > 16.65, ps < .0000001).

Construction of final lists for ERP experiment

The 93 CWs in the three sentence types were counterbalanced across three lists, each containing 31 literal, 31 metaphorical and 31 semantically anomalous sentences, so that, across all lists, all CWs appeared in each of the literal, metaphorical and anomalous sentence types, but so that no CW appeared more than once in the same list.

One hundred and twenty-four filler sentences were constructed in order to introduce syntactic variation in the stimulus material as well as to equalize the proportion of congruous and anomalous sentences in the stimulus set as a whole (to avoid response biases in the plausibility judgment task). Sixty-two of the fillers included a sentence-final semantic anomaly, and, of these, fifteen contained a literal mid-sentence CW (e.g. “Water drops were sprayed on the theme”), and sixteen contained a metaphorical mid-sentence CW (e.g. “My mind has been struggling with math for bananas”). Of the 62 non-anomalous filler sentences, 31 were literal and 31 were familiar metaphorical (mean familiarity rating in the norming study described above: 4.03, i.e. significantly more familiar than the unfamiliar metaphors from other studies: ts > 18.77, ps < .0000001). These filler sentences were added to each of the three counterbalanced lists and all sentences were then pseudo-randomized amongst the experimental sentences within each list so that no sentence type was presented on more than three consecutive trials.

Thus, within each list, each participant viewed 217 sentences altogether, 93 (43%) of which introduced a semantic anomaly. Seventy-eight sentences (36%) included a (familiar) metaphorical clause (16 of which were embedded within a semantically anomalous sentence) and 77 sentences (35%) included a literal clause (15 of which were embedded within a semantically anomalous sentence). The remaining 62 sentences (29%) did not contain either a metaphorical or literal clause as the anomaly was introduced mid-sentence.

ERP Experiment

Participants

Twenty-four participants initially took part. After exclusions (see Results), eighteen participants (10 male, 8 female) aged 18 to 21 (mean: 19.5) were included in the final behavioral and ERP analyses. Care was taken that the lists remained fully counterbalanced. All selected participants were right-handed, native American English speakers, who had not learned to speak another language fluently before the age of 5. Participants were not taking any medication, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, no learning disability and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. Written consent was obtained from all subjects before participation according to the established guidelines of Tufts University.

Stimulus Presentation

Each subject was given 21 practice trials at the start of the experiment. Experimental participants were randomly assigned to one of the three lists used for counterbalancing between participants. Participants sat in a comfortable chair in a dimly lit room separate from the experimenter and computers. Sentences were presented word by word on a computer monitor. Each trial (one sentence) began with the presentation of the word “READY”. After the participants pressed a button on a response box to indicate their readiness, a fixation point appeared at the center of the screen for 1000 ms, followed by a 100 ms blank screen, followed by the first word. Each word appeared on the screen for 400 ms with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 100 ms separating the words. The final word of each sentence appeared with a period. A 750 ms blank-screen interval followed the final word in each sentence, followed by a “?”. This cue remained on the screen until the participant made his/her response, at which point the next trial started. The participant's task was to decide whether or not each sentence made sense by pressing one of two buttons on a response box with either the left or right thumb (counterbalanced across participants). Participants were instructed to wait until the “?” cue before responding. This delayed response was designed to reduce any contamination of the ERP waveform by response sensitive components such as the P300 (Donchin & Coles 1988).

Electrophysiological Recording

Twenty-nine active tin electrodes were held in place on the scalp by an elastic cap (Electro-Cap International, Inc., Eaton, OH), see Figure 1. Electrodes were also placed below the left eye and at the outer canthus of the right eye to monitor vertical and horizontal eye movements, and on the left and right mastoids. Impedance was kept below 2.5 k! for all scalp and mastoid electrode sites and below 10 k! for the two eye channels. The EEG signal was amplified by an Isolated Bioelectric Amplifier System Model HandW-32/BA (SA Instrumentation Co., San Diego, CA) with a bandpass of 0.01 to 40 Hz and was continuously sampled at 200 Hz by an analogue-to-digital converter. The stimuli and behavioral responses were simultaneously monitored by a digitizing computer.

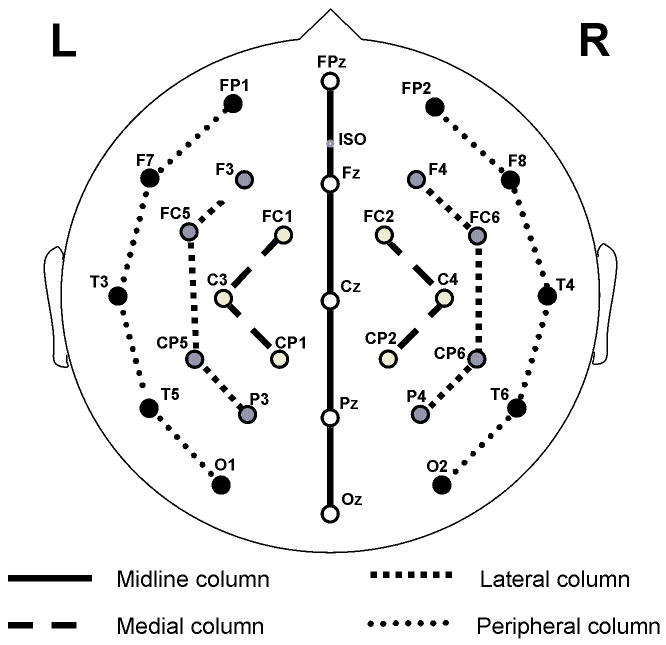

Figure 1.

Electrode Montage. Electrodes placed in the standard International 10-20 System locations included five sites along the midline (FPz, Fz, Cz, Pz, and Oz) and eight lateral sites, four over each hemisphere (F3/F4, C3/C4, T3/T4, and P3/P4). Eight additional 10-20 sites were altered to form a circle around the perimeter of the scalp. These altered sites included FP1′/FP2′ (33% of the distance along the circle between T3/T4), F7′/F8′ (67% of the distance between FPz and T3/T4), T5′/T6′ (33% of the distance between T3/T4 and Oz), and O1′/O2′ (67% of the distance between T3/T4 and Oz). In addition eight extended 10-20 system sites were also used (FC1/FC2, FC5/FC6, CP1/CP2, and CP5/CP6).

Behavioral Data Analysis

Accuracy was computed as the percentage of correct responses. A correct response was a judgment of acceptable for the literal and metaphorical sentences and unacceptable for the anomalous sentences.

Participants were excluded from the ERP analysis under two conditions: first, if they answered incorrectly to more than 14 sentences in at least one of the sentence types. Second, if they showed evidence of an inability to discriminate between the literal and anomalous sentences (the two sentence types that were easiest to objectively classify as plausible and implausible respectively), as indexed by a discriminability index (d′) (Heeger 2003) of less negative than -2.

ERP Data Analysis

Averaged ERPs, time-locked to target words, were formed off-line from trials free of ocular and muscular artifact and were quantified by calculating the mean amplitude (relative to a 100 ms prestimulus baseline) in time windows of interest. All sites were included in a systematic, comprehensive columnar “pattern of analyses” applied in prior studies (e.g. Holcomb & Grainger 2006, Kuperberg et al. 2007b), described below. This approach yielded statistical information about differences in the distribution of effects along the anterior-posterior (AP) axis of the scalp and across the two hemispheres at columns covering the whole scalp (see Figure 1).

At each column, a series of repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed. In all these ANOVAs, within-subject factors included AP Distribution (number of levels depending on the number of electrode sites along the anterior-posterior plane in each column, Figure 1), and, at the three lateral columns, Hemisphere (2 levels: left, right). In all ANOVAs, a significance level of alpha = .05 was used as, in all cases, we were testing a priori hypotheses, and the Geisser-Greenhouse correction was used in cases with more than one degree of freedom in the numerator (Greenhouse and Geisser 1959) to protect against Type 1 error resulting from violations of sphericity. In these cases, we report the original degrees of freedom with the corrected p value.

Results

Of the twenty-four subjects who initially participated, two participants were excluded because they incorrectly classified more than 14 of the metaphorical sentences as being anomalous. Four participants were excluded because, after artifact rejection (due to blinks and blocking (2) or alpha waves (2)), fewer than 17 trials remained in at least one experimental condition in the ERP experiment.

Behavioral Data

The remaining 18 participants were fairly accurate in their plausibility judgments (see Table 3). Accuracy differed across the three sentence types (F(2,34) = 33.13, p < 0.001), due to less accurate judgments to the metaphorical sentences relative to both the literal sentences (t(17) = -5.99, p < 0.001) and the anomalous sentences (t(17) = -6.41, p < 0.001), as well as less accurate judgments to the literal than to the anomalous sentences (t(17) = -2.29, p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Experiment 1: Accuracy of plausibility judgment across sentence types

| Sentence type | Mean Correct (%) |

|---|---|

| (1) Literal | 91.57 (5.09) |

| (2) Metaphorical | 77.06 (10.72) |

| (3) Anomalous | 95.52 (3.85) |

Shown are the mean percentages of correct judgments of plausible to the literal and metaphorical sentences and correct judgments of implausible to the anomalous sentences. Standard deviations are indicated in brackets.

ERP Data

Of the final dataset of 18 participants, approximately 17% of trials were rejected for artifact. Trial rejection did not differ across the three experimental conditions (F(2,34) = 0.19, p = 0.79). ERP analyses using only correctly answered trials are reported below. When all responses were included, the results were qualitatively similar.

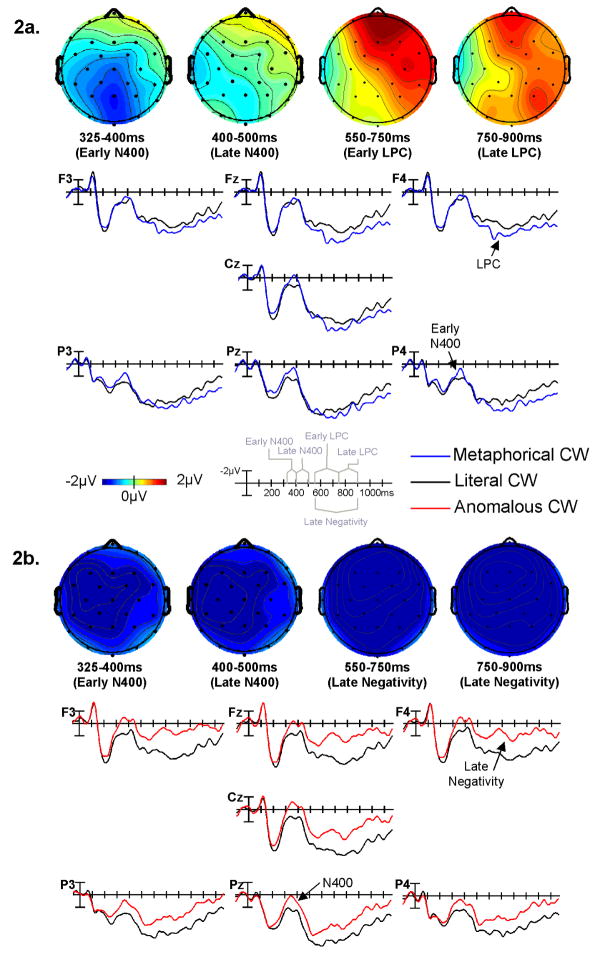

Grand-averaged ERPs elicited by the CWs in the three experimental conditions are presented at selected electrode sites in Figure 2. A negative-positive N1-P2 complex can be seen in the first 250 ms after onset of the CW, during which there were no divergences in the waveform across sentence types (no significant main effects of sentence type or interactions involving sentence type: all Fs < 1.79, all ps > 0.16).

Figure 2.

Experiment 1 – ERPs time-locked to the CWs; (2a) metaphorical vs. literal CWs; (2b) semantically anomalous vs. literal CWs

The N1/P2 was followed by a negative-going component – the N400. The negativity to the anomalous CWs continued as a prolonged negativity, relative to the literal CWs. The metaphorical CWs also appeared to evoke a small N400 that was followed by a prolonged, positive-going waveform, relative to literal CWs. Because this positivity to the metaphorical CWs may have obscured any negativity in the latter part of the N400 time-window (due to component overlap), and following previous studies (Kreher et al. 2008; Chwilla et al. 2000; Chwilla & Kolk 2003; Van Petten & Kutas 1987), the N400 negativity was examined across two time-windows: (1) the Early N400 (325-400 ms) and (2) the Late N400 (400-500 ms). The late components were also examined across two time-windows to investigate their time course: (1) 550-750 ms and (2) 750-900 ms.

For all these time windows, initial ANOVAs containing three levels of Sentence Type (literal, metaphorical, and anomalous) revealed significant main effects and/or interactions involving Sentence Type (ps < 0.05). We therefore report the effects of planned pair-wise ANOVAs that compared each sentence type with one another. We focus on main effects and interactions involving Sentence Type, which were of most theoretical interest. Any interactions between Sentence Type, Hemisphere and/or AP Distribution not noted below were all non-significant (all ps > .05). Near-significant main effects and interactions (p < .1) are only discussed in the presence of at least one other significant main effect or interaction at another column.

325-400 ms: the early N400

Anomalous vs. Literal

The waveform to the anomalous CWs was more negative than that evoked by the literal CWs, reflected by significant main effects of Sentence Type at all electrode columns (Table 4). This effect was evenly distributed across the scalp surface (no interactions between Sentence Type, AP Distribution and/or Hemisphere at any column, all Fs < 3.94, all ps > .05).

Table 4.

Experiment 1: Pair-wise ANOVAs comparing ERPs to each type of critical word in the Early N400 (325-400 ms) and Late N400 (400-500 ms) time windows (correct responses)

| Early N400 | Late N400 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F value | F value | |

| A. Anomalous versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 9.10** | 7.85** |

| S × AP | 0.93 | 0.71 | |

| Medial | S | 8.76** | 7.45** |

| S × AP | 0.54 | 0.14 | |

| S × H | 3.94+ | 10.15** (LH** > RH*) | |

| S × AP × H | 1.26 | 1.50 | |

| Lateral | S | 10.56** | 9.43** |

| S × AP | 0.34 | 0.11 | |

| S × H | 2.74 | 3.01+ (LH** > RH*) | |

| S × AP × H | 0.03 | 0.81 | |

| Peripheral | S | 10.01** | 9.07** |

| S × AP | 0.21 | 0.09 | |

| S × H | 1.62 | 2.46 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.21 | 1.18 | |

| B. Metaphorical versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 2.85 | 0.05 |

| S × AP | 4.68** (Pz*, Oz*, Cz+ > FPz, Fz) | 0.94 | |

| Medial | S | 2.60 | 0.07 |

| S × AP | 1.39 | 0.23 | |

| S × H | 0.55 | 1.37 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.13 | 1.77 | |

| Lateral | S | 2.08 | 0.09 |

| S × AP | 2.52 | 0.50 | |

| S × H | 0.73 | 1.69 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.34 | 1.30 | |

| Peripheral | S | 1.04 | 0.01 |

| S × AP | 2.50 | 0.84 | |

| S × H | 0.60 | 3.32+ (ns) | |

| S × AP × H | 1.13 | 2.77+ (ns) | |

| C. Anomalous versus Metaphorical | |||

| Midline | S | 2.20 | 6.24* |

| S × AP | 2.13 | 0.74 | |

| Medial | S | 3.03+ | 6.07* |

| S × AP | 1.96 | 0.36 | |

| S × H | 0.62 | 1.00 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.05 | 0.00 | |

| Lateral | S | 3.78+ | 6.16* |

| S × AP | 2.54 | 0.59 | |

| S × H | 0.22 | 0.01 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.36 | 0.39 | |

| Peripheral | S | 3.91+ | 7.52** |

| S × AP | 2.38 | 0.74 | |

| S × H | 0.02 | 0.07 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.88 | 1.11 | |

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

S: main effect of Sentence Type, degrees of freedom 1, 17

S × AP: interaction between Sentence Type and AP Distribution, degrees of freedom 4, 68 (midline and peripheral), 2, 34 (medial), 3, 51 (lateral)

S × H: interaction between Sentence Type and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 1, 17

S × AP × H: interaction between Sentence Type, AP Distribution and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 4, 68 (midline and peripheral), 2, 34 (medial), 3, 51 (lateral)

(ns): no significant effects found in follow-up analyses

Metaphorical vs. Literal

Metaphorical CWs evoked an early negativity effect relative to literal CWs but only at midline central and posterior sites (see Figure 2), as reflected by a significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interaction at the midline column.

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

The direct contrast between the anomalous and metaphorical sentences appeared to show a more negative early N400 to the anomalous than to the metaphorical CWs, but the main effects of Sentence Type at all columns except the midline column only approached significance (Table 4).

400-500 ms: the late N400

Anomalous vs. Literal

The N400 waveform to the anomalous CWs continued to be more negative than that evoked by the literal CWs, particularly at left-lateralized sites, reflected by significant main effects of Sentence Type at all electrode columns and Sentence Type by Hemisphere interactions that reached significance at the medial column and approached significance at the lateral column.

Metaphorical vs. Literal

In contrast to the early N400 time-window, there was no difference in the amplitude of the late N400 waveform to the metaphorical and the literal CWs at any sites, as reflected by the absence of significant main effects or interactions involving Sentence Type (all Fs < 3.32, all ps > .05).

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

A direct comparison between the anomalous and the metaphorical sentence types revealed main effects of Sentence Type at all electrode columns and no interactions (Table 4), confirming a more negative late N400 to the anomalous than to the metaphorical CWs that was evenly distributed across the scalp surface.

Later effects: 550-750 ms

Anomalous vs. Literal

The waveform to the anomalous CWs continued to be more negative than to the literal CWs at widespread sites (significant main effects of Sentence Type at all columns), an effect which was left-lateralized at the medial column (significant Sentence Type by Hemisphere interaction at the medial column), see Table 5.

Table 5.

Experiment 1: Pair-wise ANOVAs comparing ERPs to each type of critical word in the Early LPC (550-750 ms) and Late LPC (750-900 ms) time windows (correct responses)

| Early LPC | Late LPC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F value | F value | |

| A. Anomalous versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 18.21*** | 15.87*** |

| S × AP | 1.52 | 2.08 | |

| Medial | S | 16.08*** | 12.93** |

| S × AP | 2.81+ (FC1/2***, C3/4*** > CP1/2**) | 3.32+ (FC1/2*** > C3/4**, CP1/2**) | |

| S × H | 4.46* (LH*** > RH**) | 2.58 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.80 | 0.14 | |

| Lateral | S | 17.66*** | 14.86*** |

| S × AP | 3.34+ (F3/4***, FC5/6*** > CP5/6**, P3/4**) | 3.49+ (F3/4*** > FC5/6**, CP5/6**, P3/4**) | |

| S × H | 0.37 | 1.24 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.22 | 0.88 | |

| Peripheral | S | 14.27** | 13.52** |

| S × AP | 2.23 | 1.12 | |

| S × H | 0.03 | 0.10 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.48 | 1.53 | |

| B. Metaphorical versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 3.44+ | 3.29+ |

| S × AP | 3.18+ | 0.72 | |

| Medial | S | 2.19 | 1.59 |

| S × AP | 1.59 | 1.00 | |

| S × H | 11.41** (RH* > LH) | 3.98+ (RH+ > LH) | |

| S × AP × H | 7.93** (C4* > C3) | 1.20 | |

| Lateral | S | 2.26 | 1.66 |

| S × AP | 0.93 | 0.77 | |

| S × H | 10.81** (RH** > LH) | 3.08+ (RH+ > LH) | |

| S × AP × H | 3.34* (FC6**, CP6*, P4+ > FC5, CP5, P3) | 2.12 | |

| Peripheral | S | 4.64* | 2.35 |

| S × AP | 1.80 | 1.01 | |

| S × H | 16.27*** (RH*** > LH) | 5.07* (RH* > LH) | |

| S × AP × H | 5.83** (F8**, T4***, T6** > F7, T3, T5) | 3.34* (T6*, T4+ > T5, T3) | |

| C. Anomalous versus Metaphorical | |||

| Midline | S | 35.58**** | 29.87**** |

| S × AP | 7.69** (FPz****, Fz****, Cz**** > Pz***, Oz**) | 4.40* (Fz**** > FPz***, Cz***, Pz***, Oz**) | |

| Medial | S | 30.68**** | 25.05**** |

| S × AP | 8.34** (FC1/2**** > C3/4****, CP1/2****) | 6.86** (FC1/2**** > C3/4***, CP1/2***) | |

| S × H | 2.07 | 0.13 | |

| S × AP × H | 2.00 | 0.46 | |

| Lateral | S | 23.72**** | 19.77*** |

| S × AP | 7.80** (F3/4**** > FC5/6***, CP5/6***, P3/4***) | 4.47* (F3/4***, P3/4*** > FC5/6***, CP5/6***) | |

| S × H | 5.45* (RH**** > LH***) | 0.40 | |

| S × AP × H | 2.40+ (FC6****, CP6*** > FC5**, CP5**) | 1.91 | |

| Peripheral | S | 21.77*** | 16.42*** |

| S × AP | 8.53** (FP1/2****, F7/8***, O1/2*** > T3/4**, T5/6**) | 3.03+ (FP1/2*** > F7/8**, T3/4*, T5/6**, O1/2**) | |

| S × H | 9.52** (RH**** > LH**) | 2.63 | |

| S × AP × H | 3.59* (FP2****, T4***, T6*** > FP1****, T3, T5+) | 2.34 | |

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

S: main effect of Sentence Type, degrees of freedom 1, 17

S × AP: interaction between Sentence Type and AP Distribution, degrees of freedom 4, 68 (midline and peripheral), 2, 34 (medial), 3, 51 (lateral)

S × H: interaction between Sentence Type and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 1, 17

S × AP × H: interaction between Sentence Type, AP Distribution and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 4, 68 (midline and peripheral), 2, 34 (medial), 3, 51 (lateral)

Metaphorical vs. Literal

In contrast, the metaphorical CWs evoked a positivity, relative to the literal CWs (main effect of Sentence Type, significant at the peripheral column and near-significant at the midline column), which was largest at right-lateralized central sites, as reflected by significant Sentence Type by Hemisphere and Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interactions at medial, lateral and peripheral columns, see Table 5.

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

The direct comparison between the anomalous and metaphorical sentence types confirmed a more negative waveform to the anomalous CWs at widespread sites (significant main effects of Sentence Type at all columns), but largest at fronto-central sites (significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all columns) and right-lateralized (fronto-central) lateral and peripheral sites (significant Sentence Type by Hemisphere interactions at the lateral and peripheral column, and Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interactions, significant at the peripheral column and near-significant at the lateral column), see Table 5.

Later effects: 750-900 ms

Anomalous vs. Literal

The waveform to the anomalous CWs continued to be more negative than that evoked by the literal CWs (Figure 2), as reflected by significant main effects of Sentence Type at all columns, see Table 5.

Metaphorical vs. Literal

The positivity evoked by the metaphorical CWs, relative to the literal CWs, was less widespread in this later time window, with largest effects at fronto-central right-lateralized peripheral sites (significant Sentence Type by Hemisphere and Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interactions at the peripheral column), see Table 5.

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

The waveform to the anomalous CWs, relative to the metaphorical CWs, continued to be more negative at widespread sites (significant main effects of Sentence Type at all columns), again largest at fronto-central sites (Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all columns), see Table 5.

Discussion

Anomalous CWs evoked a widespread N400 that was more negative-going than that evoked by literal CWs throughout the N400 time-window (from 325-500 ms), indicating that the anomalous CWs were relatively more difficult to semantically map onto their preceding context. This negativity continued into the 550-750 and 750-900 ms time windows. This finding is consistent with other studies that have reported a sustained negativity to sentence-final semantic violations as well as to sentence-final words following mid-sentence semantic violations (Hagoort & Brown 2000; Hagoort 2003) and it is discussed further in the Discussion of Experiment 2.

An early negativity effect (from 325-400 ms) was observed at some midline posterior sites to CWs in the metaphorical relative to the literal sentences, but was not observed in the late N400 time window. One possibility is that this reflected a transient, localized N400 effect, resulting because early access to the literal meanings of the CWs resulted in problems in semantically mapping this meaning onto their metaphorical contexts. On this account, the effect was transient because the metaphorical meanings of the CWs were accessed very quickly afterwards, fitting with the metaphorical context and leading to N400 attenuation. An alternative possibility is that there was no such effect in the late N400 time window because the LPC to the CWs in the metaphorical sentences (discussed below) began within this time window, attenuating the appearance of a later N400 to the metaphorical CWs at the scalp surface.

Metaphorical CWs, relative to both other conditions, also evoked a prolonged right-lateralized positivity effect in the 550-750 ms time window and a less widespread effect in the 750-900 ms time window. As discussed in the Introduction, previous interpretations of the LPC to metaphorical (vs. literal) CWs have suggested that this effect reflects a later attempt to construct the metaphorical meaning of the sentence by subsequently retrieving the metaphorical meaning of the CW from semantic memory and integrating it with the context (Coulson & Van Petten 2002). We suggest an alternative explanation for the LPC: given that the N400 effect to the metaphorical CWs was so localized and transient, we suggest that, by 400 ms the metaphorical meaning had already been accessed (see above). However, because the literal meaning of the CW remained active, this led to the computation of conflicting implausible literal and plausible metaphorical representations of the sentence. The LPC may have been triggered by this conflict (Kolk et al. 2003; Kolk & Chwilla 2007; Kuperberg 2007a). We return to this explanation in the General Discussion.

One aim of Experiment 2 was to determine whether the localized and early N400 effect to the metaphorical (versus literal) CWs could be replicated. In addition, it remains unclear from this experiment and previous experiments (e.g. Coulson and Van Petten 2002) how the LPC evoked by the CWs in the metaphorical sentences interacts with wrap-up processes often seen on sentence-final words and also sometimes reflected by an LPC (Friedman et al. 1975, Osterhout 1997). Therefore, a second aim of Experiment 2 was to determine whether the metaphorical CWs evoked an LPC, even when they occurred at a non-sentence-final position.

Experiment 2

Introduction

In this experiment, we introduced CWs at mid-sentence positions, with at least one additional word before the sentence-final word. All sentences took the form, “NP is/was a(n) CW” followed by a prepositional or nominal phrase or a clause (see Table 1). The same three sentence types were compared (literal, metaphorical and semantically anomalous), and participants were asked to perform the same plausibility judgment task.

We addressed the following questions. First, would any N400 effect evoked by the metaphorical (versus literal) CWs still be transient and attenuated by the 400-500 ms time-window? The absence of any effect in the 400-500 ms time-window, particularly if there was no overlapping LPC effect at the CW, would support the idea that, by this time window, the meanings of metaphorical CWs are accessed and fit well with their sentence contexts. Second, would an LPC be observed at or after the metaphorical CWs in a non-sentence-final position when there was no explicit cue to wrap-up (i.e. no full stop)? One possibility was that the absence of such a cue to wrap-up might lead to an extension of an LPC effect over several words after the metaphorical CWs, i.e. the extraction of figurative meaning might be protracted, similar to the comprehension of proverbs (Katz & Ferretti 2001).

We also examined ERP effects on words following the mid-sentence CW, including the non-critical sentence-final words. We predicted that, by the end of the metaphorical sentence, any previous continued analysis would have resolved any conflict between alternative interpretations, and that there would be no additional processing costs incurred on the sentence-final words of the metaphorical relative to the literal sentences. Finally, we were interested in what waveform would be evoked by sentence-final words following anomalous CWs. We predicted that, like sentence-final CWs in Experiment 1, these would evoke a larger negativity than sentence-final words of literal sentences.

Methods

Participants

Thirty participants originally took part. After exclusions (see Results), twenty-four participants (11 male, 13 female) aged 18 to 25 (mean: 20) were included in the final behavioral and ERP analyses. None took part in the first experiment. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and characterization procedures were identical to those of Experiment 1.

Materials and Further Ratings

The sentences used as experimental stimuli in Experiment 1 were elaborated such that the CW in each sentence was followed by a prepositional or nominal phrase or a clause. This phrase or clause was the same across the three sentence types constructed for each CW (see Table 1, right; see www.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/kuperberglab/materials.htm for additional examples).

We also conducted two additional norming studies to determine whether, by the sentence-final word, plausibility was matched across the literal and metaphorical sentence types and to confirm that participants interpreted the literal sentences literally and the metaphorical sentences metaphorically (see Table 2 for results). Participants in these rating studies were undergraduate students at Tufts University who did not participate in either ERP study or any other norming study, and who gave written, informed consent before participation.

In these norming studies, the three sentence types were counterbalanced across three lists, each presented in pseudo-random order to 40 participants in total. All participants were asked to judge the plausibility and naturalness of each sentence on a scale from 1 (bad) to 5 (good). In addition, the participants were asked to write a short explanation of the meaning of each sentence (an original set of 24 participants) or the underlined CW (a subsequent set of 16 participants).

For the plausibility ratings, literal and metaphorical sentences did not differ significantly from one another on subjects or items analyses (ts < 1.20, ps > 0.23). As expected, the semantically anomalous sentences had a lower average rating that differed significantly from both the other two sentence types on both subjects and items analyses (ts > 29.8, ps < 0.001).

As the plausibility ratings only allowed us to distinguish the anomalous sentences from the other two sentence types, we used the descriptions of the sentences/CWs as a basis for distinguishing the literal and metaphorical sentence types. Each description of literal and metaphorical sentences/CWs (given by the 40 raters above) was classified by two independent researchers (including the first author) as reflecting a literal, a metaphorical or a semantically anomalous interpretation (scored as ‘1’, ‘2’ or ‘3’, respectively). Explanations that the two researchers did not agree on were discussed with two additional researchers of the same lab until a consensus was reached. The resulting scores for each of the descriptions by the 40 raters were used as the basis for a statistical analysis to determine how the literal and metaphorical sentence types were interpreted. Average scores for the literal and metaphorical sentences are given in Table 2. Subjects (n = 40) and items (n = 93) analyses revealed significant differences between the literal and the metaphorical sentences (ts > 40, ps < 0.001).

Construction of Final Lists for ERP Experiment

As in Experiment 1, each list contained 31 literal, 31 metaphorical and 31 semantically anomalous sentences, counterbalanced across participants. One hundred and twenty-four filler sentences were added to the experimental sentences, and half of these included a semantic anomaly, 46 of which became apparent on the sentence-final word, thus encouraging participants to read until the end of all sentences before making plausibility decisions in the ERP experiment. Of the 46 sentence-final anomalous filler sentences, half contained a literal mid-sentence CW and half contained a metaphorical mid-sentence CW. Of the 62 non-anomalous filler sentences, half were literal and half were familiar metaphors.

Thus, within each list, each participant viewed 217 sentences altogether, 93 (43%) of which introduced a semantic anomaly. Eighty-five sentences (39%) included a (familiar) metaphorical clause (23 of which were embedded within a semantically anomalous sentence) and 85 sentences (39%) included a literal clause (again, 23 of which were embedded within a semantically anomalous sentence). The remaining 47 sentences (22 %) did not contain either a metaphorical or literal clause as the anomaly was introduced mid-sentence.

Experimental Procedures, Data Acquisition and Analysis

These were identical to those described in Experiment 1.

Results

Of the thirty subjects who initially participated, three were excluded because they showed clear behavioral response biases, reflected by d′ scores of less negative than -2. Three additional participants were excluded because, after artifact rejection (due to blinks (2) or alpha waves (1)), fewer than 16 trials remained in at least one experimental condition.

Behavioral Data

The remaining 24 participants were fairly accurate in their plausibility judgments (see Table 6). Accuracy differed across the three sentence types (F(2,46) = 29.06, p < 0.001), due to less accurate judgments of the metaphorical sentences relative to both the literal sentences (t(23) = 6.02, p < 0.001) and the anomalous sentences (t(23) = 6.20, p < 0.001), as well as less accurate judgments of the literal than the anomalous sentences (t(23) = -2.23, p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Experiment 2: Accuracy of plausibility judgment across sentence types

| Sentence type | Mean Correct (%) |

|---|---|

| (1) Literal | 91.13 (6.94) |

| (2) Metaphorical | 77.96 (11.32) |

| (3) Anomalous | 95.97 (6.54) |

Shown are the mean percentages of correct judgments of plausible to the literal and metaphorical sentences and correct judgments of implausible to the anomalous sentences. Standard deviations are indicated in brackets.

ERP Data

Of the final dataset of 24 participants, approximately 9% of trials were rejected for artifact. Trial rejection did not differ across the three experimental conditions (F(2,46) = 0.446, p = 0.60). ERP analyses using only correctly answered trials are reported below. When all responses were included, the results were qualitatively similar except where explicitly noted below.

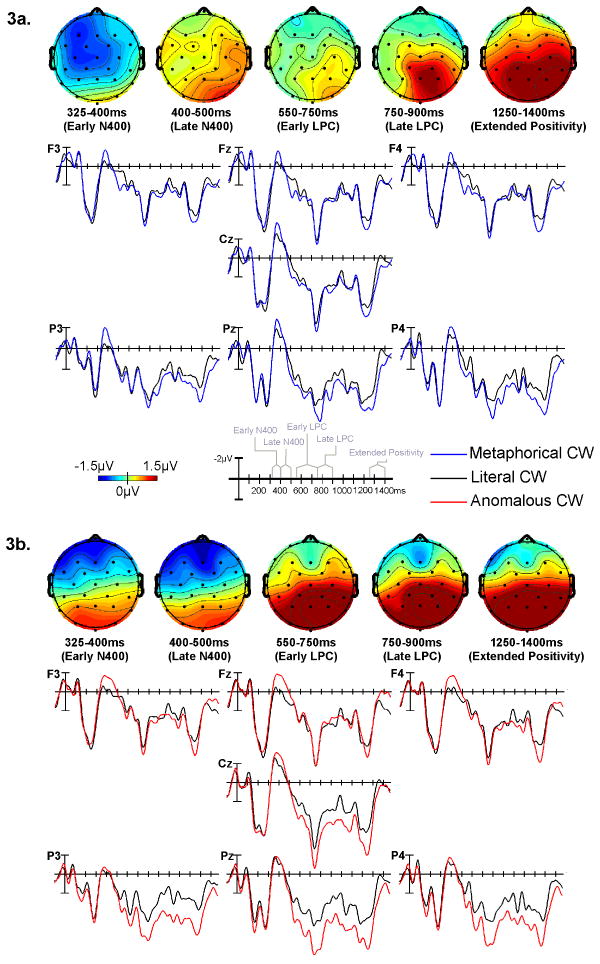

ERPs time-locked to the CW

Grand-average ERPs elicited by the CWs in the three experimental conditions are presented at selected electrode sites in Figure 3. A negative-positive complex can be seen in the first 250 ms after onset of the CW, the N1-P2 complex, during which there were no divergences in the waveform across sentence types (no significant main effects of sentence type or interactions involving sentence type: all Fs < 1.60, all ps > 0.19).

Figure 3.

Experiment 2 – ERPs time-locked to the CWs; (3a) metaphorical vs. literal CWs; (3b) semantically anomalous vs. literal CWs

The N1/P2 was followed by a negative-going component with a peak amplitude between 325 and 500 ms. This appeared to be more negative to the anomalous than to the literal CWs, particularly at frontal and frontocentral sites (Figure 3). Although, as explained in the Discussion, this does not reflect the normal centro-posterior distribution of the N400 effect, we will refer to this negativity as an anterior N400 to reflect its sensitivity to semantic anomaly.

As in Experiment 1, the time course of modulation of the negativity to the anomalous and metaphorical CWs, relative to the literal CWs, appeared to differ, with an early effect to the metaphorical CWs appearing at some electrode sites. To explore these differences, the same two time windows as in Experiment 1 were used to examine this negativity: (1) the Early N400 (325-400ms) and the (2) Late N400 (400-500ms).

The negativity was followed by a prolonged, positive-going waveform, starting from approximately 550 ms after the onset of the CW and continuing well after the onset of the word following the CW (termed the CW+1). The LPC effect to metaphorical CWs (relative to literal CWs) seemed to start later than in Experiment 1. Therefore, the LPC was examined in the early LPC (550-750 ms after CW onset) and late LPC (750-900 ms after CW onset) time windows. As we expected any late positive effect to be carried over several words, and because inspection of the data revealed a more positive waveform on the first word following the metaphorical and anomalous CWs, we also examined the time window of 1250-1400 ms after CW onset (Extended Positivity, corresponding to 750-900ms after the CW+14).

For all these time windows, initial ANOVAs containing three levels of Sentence Type (literal, metaphorical, and anomalous) revealed significant main effects and/or interactions involving Sentence Type (ps < 0.05) or near-significant main effects or interactions involving Sentence Type (ps < 0.1 at the medial column in the 325-400 ms time window, at the lateral column in the 750-900 ms time window and at the midline column in the 1250-1400 ms time window). We therefore report the effects of planned pair-wise ANOVAs that compared each sentence type with one another, in the same manner as for Experiment 1.

325-400 ms: the early N400

Anomalous vs. Literal

A central and anterior distribution of the larger N400 to the anomalous (relative to the literal) CWs (Figure 3) was reflected by Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions that reached or approached significance at all columns (Table 7).

Table 7.

Experiment 2: Pair-wise ANOVAs comparing ERPs to each type of critical word in the Early N400 (325-400 ms) and Late N400 (400-500 ms) time windows (correct responses)

| Early N400 | Late N400 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F value | F value | |

| A. Anomalous versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 1.77 | 1.72 |

| S × AP | 4.51* (FPz**, Fz* > Cz, Pz, Oz) | 5.12** (FPz*, Fz* > Cz, Pz, Oz) | |

| Medial | S | 1.77 | 2.27 |

| S × AP | 2.87+ (FC1/2+ > C3/4, CP1/2) | 4.31* (FC1/2+ > C3/4, CP1/2) | |

| S × H | 0.73 | 0.20 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.94 | 2.97+ | |

| Lateral | S | 1.87 | 1.99 |

| S × AP | 3.43+ (FC5/6*, F3/4+ > CP5/6, P3/4) | 3.88* (F3/4+, FC5/6+ > CP5/6, P3/4) | |

| S × H | 0.47 | 0.25 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.67 | 0.56 | |

| Peripheral | S | 1.38 | 1.70 |

| S × AP | 6.68** (FP1/2*, F7/8* > T3/4, T5/6, O1/2) | 6.05** (FP1/2*, F7/8* > T3/4, T5/6, O1/2) | |

| S × H | 0.47 | 0.45 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.40 | 0.46 | |

| B. Metaphorical versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 0.93 | 0.68 |

| S × AP | 0.97 | 0.08 | |

| Medial | S | 1.56 | 0.30 |

| S × AP | 0.14 | 0.33 | |

| S × H | 3.41+ (ns) | 4.27* (ns) | |

| S × AP × H | 3.24* (C3+ > C4) | 4.07* (ns) | |

| Lateral | S | 1.51 | 0.62 |

| S × AP | 0.51 | 0.53 | |

| S × H | 3.64+ (LH+ > RH) | 2.88 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.81 | 1.87 | |

| Peripheral | S | 0.47 | 2.17 |

| S × AP | 0.41 | 0.11 | |

| S × H | 2.83 | 2.69 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.73 | 1.23 | |

| C. Anomalous versus Metaphorical | |||

| Midline | S | 0.03 | 4.74* |

| S × AP | 2.47+ (ns) | 3.56* (FPz*, Fz**, Cz+ > Pz, Oz) | |

| Medial | S | 0.01 | 4.71* |

| S × AP | 3.95* (ns) | 5.52* (FC1/2*, C3/4* > CP1/2) | |

| S × H | 0.92 | 1.72 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.36 | 0.35 | |

| Lateral | S | 0.00 | 4.84* |

| S × AP | 4.59* (ns) | 5.53* (F3/4*, FC5/6** > CP5/6, P3/4) | |

| S × H | 1.46 | 1.00 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.08 | 0.60 | |

| Peripheral | S | 0.15 | 6.45* |

| S × AP | 3.98* (ns) | 3.63* (FP1/2*, F7/8**, T3/4** > T5/6, O1/2) | |

| S × H | 0.71 | 0.43 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.69 | 1.19 | |

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

S: main effect of Sentence Type, degrees of freedom 1, 23

S × AP: interaction between Sentence Type and AP Distribution, degrees of freedom 4, 92 (midline and peripheral), 2, 46 (medial), 3, 69 (lateral)

S × H: interaction between Sentence Type and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 1, 23

S × AP × H: interaction between Sentence Type, AP Distribution and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 4, 92 (midline and peripheral), 2, 46 (medial), 3, 69 (lateral)

(ns): no significant effects found in follow-up analyses

Metaphorical vs. Literal

The metaphorical CWs appeared to evoke an early negativity effect (relative to the literal CWs) that was most robust over the left hemisphere, see Figure 3. This was reflected by a significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interaction at the medial column5.

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

A direct contrast between CWs in the anomalous and metaphorical sentences revealed significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions that reached or approached significance in all columns (Table 7). This appeared to be due to more negative ERPs to anomalous than to metaphorical CWs at anterior electrode sites but a reversal of this effect at posterior sites (Figure 3). Follow-up analyses, however, failed to reveal significant effects at any electrode sites (all ps > .1).

400-500 ms: the late N400

Anomalous vs. Literal

The waveform to the anomalous CWs continued as more negative than that evoked by the literal CWs, particularly at more anterior sites, reflected again by significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all electrode columns (Table 7).

Metaphorical vs. Literal

In contrast to the early N400 time-window, the waveform to the metaphorical CWs appeared to become more positive than that to literal CWs, particularly at right-lateralized electrode sites, as reflected by a Sentence Type by Hemisphere as well as a Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interaction at the medial column, but follow-up analyses failed to show significant differences between the waveforms at any electrode sites within this column (all ps > .1).

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

A direct comparison between the anomalous and the metaphorical sentence types revealed main effects of Sentence Type and significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all electrode columns (Table 7), confirming a more negative late anterior N400 to the anomalous than to the metaphorical CWs, particularly at frontal and central sites.

550-750 ms: the early LPC

Anomalous vs. Literal

In the early LPC time window, the waveform to the anomalous CWs became more positive than to the literal CWs, particularly at posterior sites (Figure 3), as reflected by significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all columns (Table 8).

Table 8.

Experiment 2: Pair-wise ANOVAs comparing ERPs to each type of critical word in the early LPC (550-750 ms), late LPC (750-900 ms) and Extended Positivity (1250-1400 ms) time windows (correct responses)

| Early LPC | Late LPC | Extended Positivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F value | F value | F value | |

| A. Anomalous versus Literal | ||||

| Midline | S | 1.46 | 1.70 | 2.62 |

| S × AP | 7.63** (Pz**, Oz** > FPz, Fz, Cz) | 5.69** (Pz**, Oz* > FPz, Fz, Cz) | 4.58* (Pz**, Oz** > Cz+, FPz, Fz) | |

| Medial | S | 1.37 | 1.59 | 3.18+ |

| S × AP | 8.94** (CP1/2+ > FC1/2, C3/4) | 8.04** (CP1/2* > FC1/2, C3/4) | 6.82** (CP1/2** > FC1/2, C3/4) | |

| S × H | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.47 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.53 | 1.08 | 1.08 | |

| Lateral | S | 1.42 | 1.67 | 3.46+ |

| S × AP | 5.17* (P3/4*, CP5/6+ > F3/4, FC5/6) | 4.80* (P3/4*, CP5/6+ > F3/4, FC5/6) | 8.04** (CP5/6**, P3/4** > F3/4, FC5/6) | |

| S × H | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.56 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.05 | 0.57 | 1.29 | |

| Peripheral | S | 1.44 | 1.70 | 2.22 |

| S × AP | 7.69** (T5/6*, O1/2** > FP1/2, F7/8, T3/4) | 5.36* (T5/6**, O1/2** > FP1/2, F7/8, T3/4) | 7.26** (T5/6**, O1/2** > FP1/2, F7/8, T3/4) | |

| S × H | 0.53 | 0.90 | 1.61 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.77 | |

| B. Metaphorical versus Literal | ||||

| Midline | S | 0.09 | 1.41 | 2.91+ |

| S × AP | 0.06 | 0.65 | 1.34 | |

| Medial | S | 0.12 | 1.10 | 3.72+ |

| S × AP | 0.00 | 1.86 | 1.56 | |

| S × H | 2.48 | 1.03 | 0.49 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.21 | 2.12 | 0.97 | |

| Lateral | S | 0.14 | 0.89 | 4.40* |

| S × AP | 0.11 | 0.66 | 2.43 | |

| S × H | 0.94 | 0.52 | 1.23 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.19 | 2.97* (P4+ > P3) | 0.45 | |

| Peripheral | S | 0.44 | 1.21 | 3.87+ |

| S × AP | 0.24 | 0.67 | 4.83* (T3/4*, T5/6***, O1/2** > FP1/2, F7/8) | |

| S × H | 0.38 | 0.37 | 1.18 | |

| S × AP × H | 1.74 | 2.27+ (O2* > O1) | 1.13 | |

| C. Anomalous versus Metaphorical | ||||

| Midline | S | 0.97 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| S × AP | 4.62* (Pz*, Oz* > FPz, Fz, Cz) | 2.08 | 1.07 | |

| Medial | S | 0.81 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| S × AP | 5.53* (CP1/2+ > FC1/2, C3/4) | 2.39 | 3.40+ | |

| S × H | 0.92 | 0.36 | 0.00 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.12 | |

| Lateral | S | 0.85 | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| S × AP | 4.53* (P3/4* > F3/4, FC5/6, CP5/6) | 1.90 | 2.09 | |

| S × H | 0.43 | 0.32 | 0.07 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.96 | |

| Peripheral | S | 0.50 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| S × AP | 4.26* (O1/2**, T5/6+ > FP1/2, F7/8, T3/4) | 1.85 | 0.52 | |

| S × H | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | |

| S × AP × H | 0.59 | 2.69+ | 1.10 | |

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

S: main effect of Sentence Type, degrees of freedom 1, 17

S × AP: interaction between Sentence Type and AP Distribution, degrees of freedom 4, 68 (midline and peripheral), 2, 34 (medial), 3, 51 (lateral)

S × H: interaction between Sentence Type and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 1, 17

S × AP × H: interaction between Sentence Type, AP Distribution and Hemisphere, degrees of freedom 4, 68 (midline and peripheral), 2, 34 (medial), 3, 51 (lateral)

Metaphorical vs. Literal

In contrast, within this time window the waveform to the metaphorical CWs was no more positive than to the literal CWs, as reflected by the absence of main effects or interactions involving sentence type at any columns (all Fs < 2.48, all ps > .1).

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

This direct comparison confirmed a more positive waveform to the anomalous CWs at posterior sites, as reflected by significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all columns.

750-900 ms: the late LPC

Anomalous vs. Literal

The posterior positivity to the anomalous CWs relative to the literal CWs continued within the late LPC time-window, as reflected by significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all electrode columns (Table 8).

Metaphorical vs. Literal

In contrast to the early LPC, the metaphorical CWs also evoked a positivity relative to the literal CWs at some right-lateralized posterior sites, as reflected by significant or marginally significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interactions at the lateral and peripheral column.

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

This positive deflection to the metaphorical CWs within this time window was not significantly different from the deflection to the anomalous CWs: a direct comparison between them failed to reveal any significant main effects or interactions involving Sentence Type at any columns (all Fs < 2.69, all ps > .05).

1250-1400 ms: the Extended Positivity6

Anomalous vs. Literal

An additional positive peak in the waveform was seen from approximately 1250-1400 ms following the onset of the CW. This corresponded to a positive-going peak at 750-900 ms to the CW+1 (Figure 3). This Extended Positivity was greater to the anomalous than the literal CWs, particularly at posterior sites, as reflected again by significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions at all electrode columns (Table 8).

Metaphorical vs. Literal

Once again, the metaphorical CWs also evoked a more positive waveform relative to the literal CWs, reflected by significant or marginally significant main effects of Sentence Type at all columns and a significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution interaction at the peripheral column (Table 8).

Anomalous vs. Metaphorical

The Extended Positivity to the metaphorical CWs was again not statistically different from that to the anomalous CWs, as reflected by an absence of main effects or interactions involving Sentence Type (all Fs < 3.40, all ps > 0.05).7

ERPs time-locked to the sentence-final word

At the sentence-final word, there were no differences across conditions in the N1-P2 complex over the first 250 ms after word onset (all Fs < 2.02, all ps >.11).

The N400 and the later effects to the sentence-final words (SFWs) were compared across the three sentence types through a statistical analysis of two time windows after onset of the sentence-final word: the 300-500 ms and 550-900 ms, respectively.

300-500 ms: the N400 on the sentence-final word

Anomalous vs. Literal

The anomalous SFWs evoked a widespread N400 effect relative to the literal SFWs (Figure 4), as reflected by main effects of Sentence Type that reached significance at all columns. There were also Sentence Type by AP Distribution interactions that reached or approached significance at the midline and the lateral columns and a significant Sentence Type by AP Distribution by Hemisphere interaction at the lateral column, reflecting a more negative waveform at posterior and right-lateralized sites (Table 9).

Figure 4.

Experiment 2 – ERPs time-locked to the SFWs; (left) SFWs in metaphorical vs. literal sentences; (right) SFWs in semantically anomalous vs. literal sentences

Table 9.

Experiment 2: Pair-wise ANOVAs comparing ERPs to each type of sentence-final word in the N400 (300-500 ms) and later (550-900 ms) time windows (correct responses)

| N400 | 550-900 ms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | F value | F value | |

| A. Anomalous versus Literal | |||

| Midline | S | 8.31** | 8.41** |

| S × AP | 5.03* (Cz**, Pz**, Oz* > FPz, Fz) | 3.47* (Cz**, Pz**, Oz* > FPz, Fz) | |

| Medial | S | 10.73** | 9.73** |

| S × AP | 1.98 | 0.40 | |