Abstract

Bivalent molecules containing two β-turn mimics with side-chains that correspond to hot-spots on the neurotrophin NT-3 were prepared. Binding assays showed the mimetics to be selective TrkC ligands, and biological assays showed one mimetic to be an antagonist of the TrkC receptor.

Neurotrophin growth factors have activities that might be useful in clinical settings, particularly with respect to maladies that affect the nervous system such as neurodegeneration, or pain.1,2 These growth factors are also implicated in cancer progression (e.g. TrkC in breast cancer). However, even apart from the usual problems associated with protein-based pharmaceuticals (eg cost, proteolytic and metabolic stabilities, immune responses), there are side-effects and potential toxicity factors that could logically be attributed to the fact that the neurotrophins are not entirely selective for their corresponding Trk receptors, and they all bind the p75 receptor.3 Binding to the latter is particularly undesirable because it tends to cause very different effects to activation of the Trk receptors.4 For these reasons, there is a pressing need for the development of small molecules that selectively bind to and regulate the function of Trk receptors.

Our approach to the design of Trk ligands has been to mimic the β-turn regions of the parent neurotrophins.5–7 Cyclic monovalent compounds (one turn mimic) have proven to be useful Trk agonists (or partial agonists)8 or antagonists.9 Bivalent compounds based on two macrocyclic turn mimics in one molecule10 have been identified as TrkA antagonists,11 or TrkC agonists.12 Selectivities for the TrkA and C receptors were achieved by using amino acid side chains corresponding to β-turns in the parent neurotrophin ligands that constitute hot-spots for the interactions of these with their Trk receptors. However, the factors that determine if the ligand is an agonist or an antagonist are more subtle. Two key molecular parameters that influence this are likely to be the scaffold used to form the turn mimic, and the spacing between them in the bivalent constructs.

This communication introduces a new type of turn mimic A based on diketopiperazines (DKPs), a scaffold that is more commonly used for forming compounds of the type B. A strategy for making bivalent molecules containing two type-A units at variable spacings is also described. Cell-based binding, biological, and biochemical signal transduction assays indicate that one of these bivalent molecules is one of the first small molecule TrkC antagonists to be reported to date.9

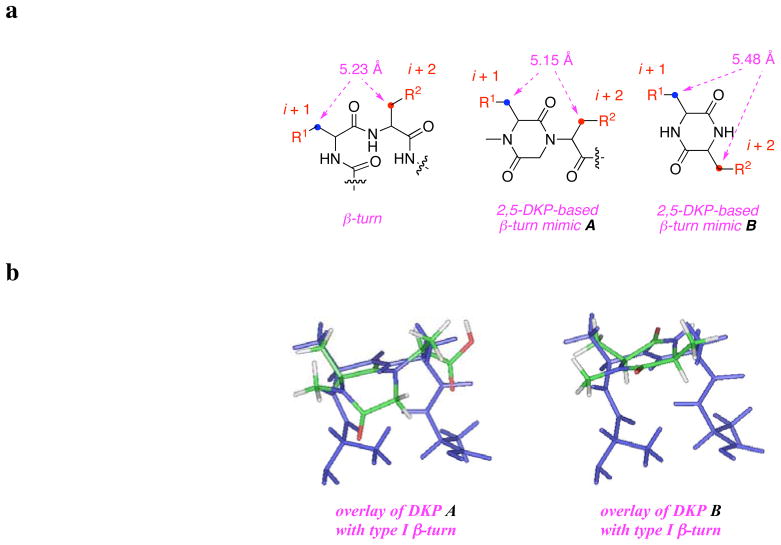

The guiding hypothesis behind our latest designs of β-turn mimics12,13 is that the separation between the Cβ atoms is critical. Figure 1 shows this distance for an ideal type 1 turn is ca 5.2 Å. Recently we reported β-turn mimics that could readily attain conformations with Cβ-separations corresponding to this distance, even though they were not the global minimum.12,13 Modelling shows that DKPs B have Cβ-separations of almost 5.5 Å, ie a little too long. In any case, these molecules are well represented in many compound collections.14 Consequently, the less common substitution pattern in A was considered.11,15,16 Here the Cβ-spacing, 5.1 – 5.2 Å, matches type I turns closely, and the structures explore a different region of diversity space.

Figure 1.

a. Key distance of Cβ-separations of the i + 1 to i + 2 residues of a type I β-turn and of the monovalent turn mimics A and B featured here; b. comparative overlay of the two types of 2,5-DKP mimics (colored) onto a type I β-turn (blue).

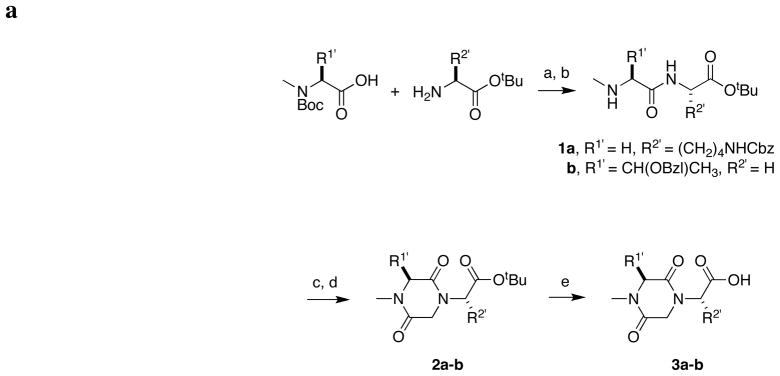

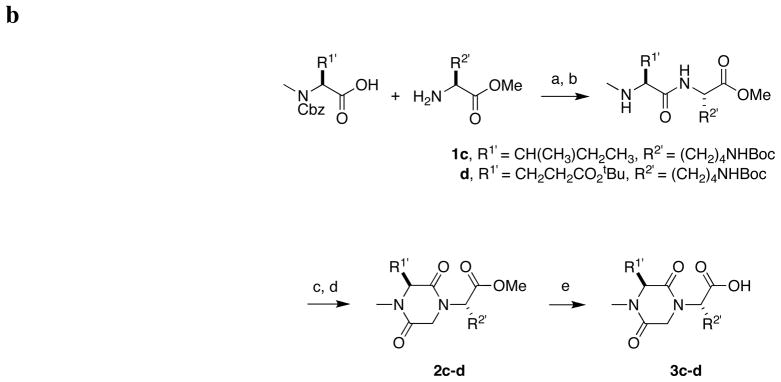

Scheme 1a and b illustrate two approaches used to make the target type A DKPs (full details are given in the supporting). Two approaches were necessary to make it possible to use the most readily available protected amino acids, and the appropriate side-chain masking groups. The key difference between the two routes is that in the first, acid-based deprotection of Boc groups (without removing the tert-butyl ester)17 is involved early in the synthesis, whereas this is replaced by hydrogenolysis of Cbz protection in the second.

Scheme 1.

Solution phase synthesis of monomeric DKP-based peptidomimetics. Parts a and b refer to syntheses of the monovalent scaffolds, and parts c deals with functionalization of these with linker fragments.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1-ethyl-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), N-methylmorpholine (NMM), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; (b) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/CH2Cl2, 0 – 25 °C, 2 h; (c) bromoacetyl bromide, 0.5 M K2CO3 (aq), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 2 h; (d) i 50 % NaOH(aq), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; (e) TFA, Pr3SiH, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 10 h.

Reagents and conditions: (a) EDCI, HOBt, NMM, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; (b) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 25 °C, 12 h; (c) bromoacetyl bromide, 0.5 M K2CO3 (aq), CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 2 h; (d) 50 % NaOH (aq), CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; (e) Me3SnOH, 1,2-dichloroethane, 80 °C, 6 h.

Reagents and conditions:

For 4a and 4e: 3a, (a) (i) short or long linker, EDCI, HOBt, NMM, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; (ii) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 25 °C, 16 h; (iii) Boc anhydride, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h;

For 4b and 4f: 3b, (b) (i) short or long linker, EDCI, HOBt, NMM, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h; (ii) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 25 °C, 16 h;

For 4c, d and 4g, h: 3c or 3d, (c) short or long linker, EDCI, HOBt, NMM, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 12 h.

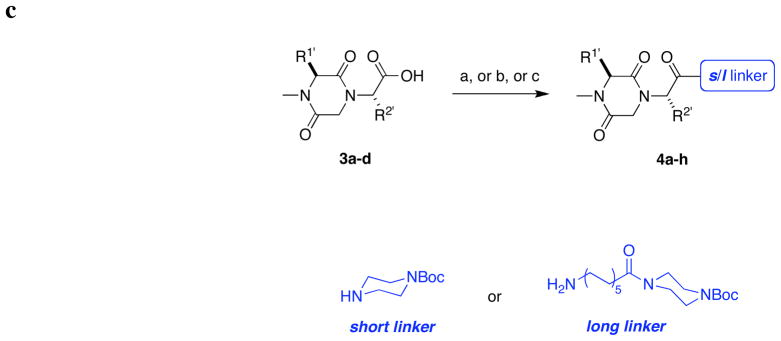

Scheme 1c illustrates how “short” s and “long” l piperazine-based linkers were coupled to the different peptidomimetics. At the conclusion of the synthesis, four different monovalent peptidomimetics were generated, each of these was functionalized with the short s and long l linker systems to give a total of eight monovalent starting materials (Table 1). The short linker was chosen because it is a compact structure formed from a heterocycle that is common in drug-design. Simple modeling experiments showed that when two long linkers of the type shown were combined then this would give a spacing of the turn mimics that is appropriate for the largest separations of the turns in the neurotrophins. Combinations of the long and short linkers would span appropriate intermediate distances.

Table 1.

Monovalent peptidomimetics 4a–h.

| compound | R1′ | R2′ | linker |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | H | short | |

| 4b | H | short | |

| 4c | short | ||

| 4d | short | ||

| 4e | H | long | |

| 4f | H | long | |

| 4g | long | ||

| 4h | long |

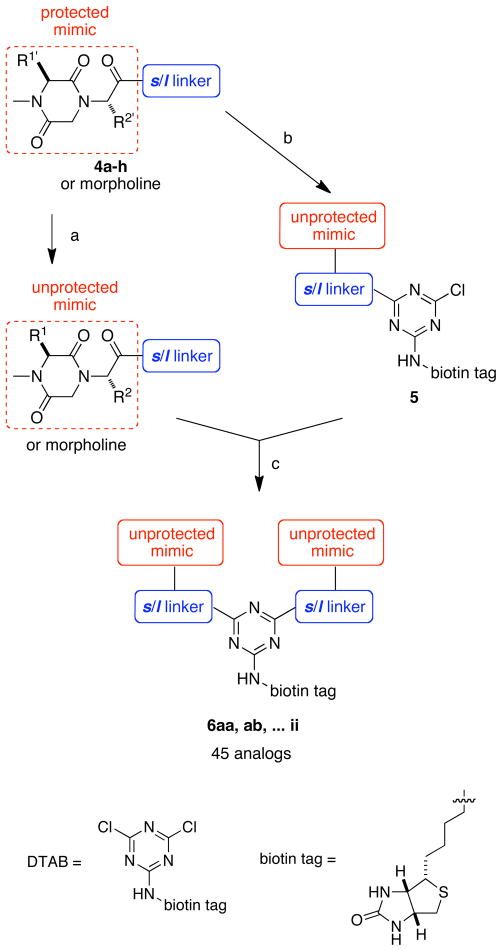

The next step in syntheses was to form a library of bivalent molecules 6 from the eight key monovalent systems 4. Solution phase methodology for doing this type of combination has been published by us.13 Briefly, this relies on suppression of the rate of SNAr reactions in apolar solvents to stop the initial reaction after one displacement, then completion of the reaction in a more polar solvent. Scheme 2 shows how this method was used to form compounds 4.

Scheme 2.

Solution phase synthesis of biotin-labeled bivalent peptidomimetic library.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1:1 TFA/CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 10 h; (b) (i) 1:1 TFA/CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 10 h; (ii) DTAB, K2CO3, DMSO, 25 °C, 2 h; (c) K2CO3, DMSO, 25 °C, 5–7 d.

Methods used in Scheme 2 mean that a triazine forms the core of every bivalent molecule 6. However, this heterocycle can be used; it has a substitution site for a “third group” to facilitate in vitro assays (or for other purposes, not relevant here). In this study, biotin derivatives were chosen to occupy this position (“biotin tag”) because they facilitate direct binding assays via fluorescence activated cell sorting, tend to increase the water solubilities of the molecules, but do not impact the measured outputs from other assays (eg 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide {MTT} in cell survival assays).

Table 2 shows the purities obtained for the library of crude samples from Scheme 2. All the compounds were then purified via preparative reverse phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) to give samples that were more than 95 % pure in all cases.

Table 2.

HPLC purities of the bivalent turn mimics 6 prepared from monovalent mimics 4a–h as assessed by UV detection.

| ia | 6ii | purities(%) | |||||||

| 4a | 6ai | 6aa | below 70 | ||||||

| 4b | 6bi | 6ab | 6bb | 70 – 85 | |||||

| 4c | 6ci | 6ac | 6bc | 6cc | 85 and up | ||||

| 4d | 6di | 6ad | 6bd | 6cd | 6dd | ||||

| 4e | 6ei | 6ae | 6be | 6ce | 6de | 6ee | |||

| 4f | 6fi | 6af | 6bf | 6cf | 6df | 6ef | 6ff | ||

| 4g | 6gi | 6ag | 6bg | 6cg | 6dg | 6eg | 6fg | 6gg | |

| 4h | 6hi | 6ah | 6bh | 6ch | 6dh | 6eh | 6fh | 6gh | 6hh |

| i | 4a | 4b | 4c | 4d | 4e | 4f | 4g | 4h | |

“i” stands for morpholine, which was used as “cap” in place of the monovalent peptidomimetics to give control compounds that have none or one peptidomimetic and biotin.

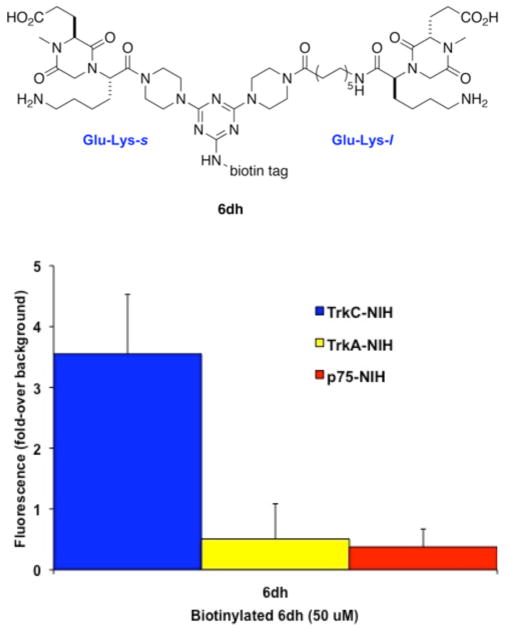

The compounds in the DKP library described above were assayed in binding assays, biological assays, and biochemical signal transduction assays as described previously.18 In the binding studies, the biotinylated compounds were assayed by flow cytometry (fluorescence activated cell sorting, {FACS}), using avidin conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate for detection. FACS assays measuring the direct binding to NIH-3T3 cells stably transfected to express TrkC. As controls, NIH-3T3 cells were stably transfected to express neurotrophin receptors TrkA, or p75, or a different receptor tyrosine kinase, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R). Of the 45 compounds scanned by FACS, one compound, the one made from combination of deprotected forms of 4d and 4h, hereafter called 6dh, showed selective TrkC binding (Figure 2). This compound binds selectively to TrkC-expressing cells, but it does not bind to NIH-3T3 cells expressing TrkA or p75 (Figure 2), or IGF-1R (not shown).

Figure 2.

Direct binding of biotin-peptidomimetic 6dh to TrkC-expressing cells. Cells expressing the indicated receptor were first bound at 4 °C with test ligand (50 μM), followed by fluorescein-avidin. After washing, cells were analyzed by FACScan/CellQuest. The background mean channel fluorescence (MCF) of NIH-IGF-1R were subtracted to analyze the specific MCF binding to test cells. Results shown are fluorescence ± standard error of mean (SEM), n =3 independent experiments.

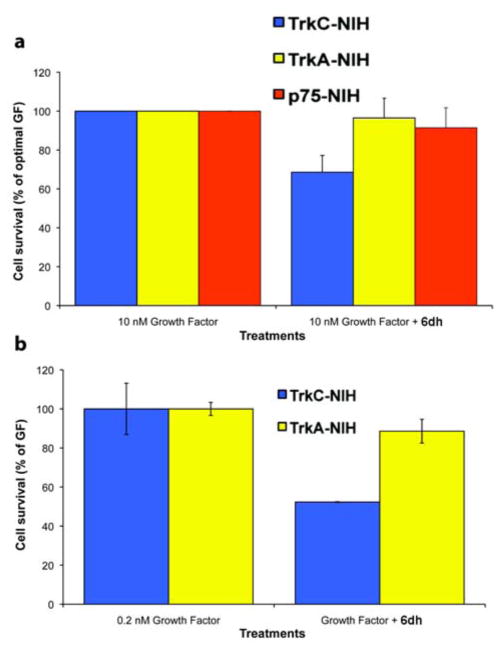

The effects of the peptidomimetics on receptor-mediated cell survival of NIH-3T3 cells expressing TrkA, TrkC or IGF-1R were also tested. Biological assays tested cell survival in quantitative MTT assays. When cells were placed in serum-free media (SFM) they died by apoptosis. In these conditions, cell death can be prevented by their appropriate growth factors (NIH-TrkA is protected by NGF, NIH-TrkC is protected by neurotrophin-3 {NT-3}, NIH-IGF-1R is protected by IGF-1). Growth factor protection of cells from apoptosis in SFM is dose-dependent, and suboptimal doses of growth factor can be used that result quantitatively and consistently in reduced survival.

Compound 6dh at 20 μM was significantly antagonistic to TrkC–NT-3 functional interactions. It reduced the trophic activity of optimal (10 nM) NT-3 to ~70% (Figure 3a). Antagonism was TrkC selective because this mimetic did not antagonize the protective function of NGF upon TrkA cells or the function of IGF-1 on IGF-1R (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Mimetic 6dh antagonizes NT-3 action in cell survival assays. NIH-3T3 cells expressing either TrkA or TrkC or IGF-1R were cultured in SFM supplemented with optimal (a, 10 nM) or sub-optimal (b, 0.2 nM) concentrations of the appropriate growth factor (GF) ± peptidomimetic (20 μM). Survival was measured in MTT assays, and was calculated relative to optimal growth factor-mediated survival (100%). Results shown are average ± sd.

For comparison, sub-optimal doses of NT-3 (0.2 nM) which affords ~40–50% of maximal cell survival were also tested. The data show the effects of NT-3 on TrkC cells is antagonized more easily by 6dh under these conditions, but also in a selective manner (Figure 3b). In addition, control cell cytotoxicity assays demonstrated 6dh were non-toxic at all doses tested (data not shown) indicating selective antagonism is due to antagonism of functional TrkC–NT-3 interactions, and not due to selective cytotoxicity.

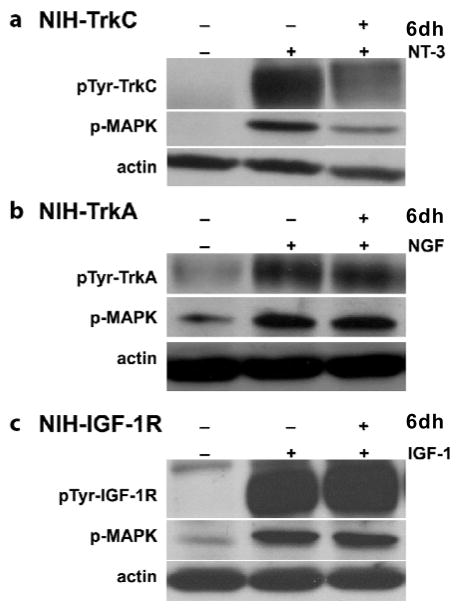

Biochemical assays of signal transduction were also performed on the lead compound, 6dh. The phosphotyrosine (pTyr) content of TrkC can be used as a measure of activation because this receptor is a receptor tyrosine kinase. Moreover, the phosphorylated state of the downstream signaling protein with extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) 1,2 can also be measured; as it is known to be activated by TrkC-signals (Figure 4).19 Cells were exposed to growth factor (2 nM) for 20 min ± 6dh (20 μM), and detergent lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies directed to phospho-tyrosine or to phospho-Erk1,2. Antibodies directed to actin demonstrated equal protein loading and this signal is used to standardize the results.

Figure 4.

Effect of 6dh on TrkC receptor phosphorylation and MAPK activation in NIH3T3 TrkC cells. Cells were exposed to the indicated peptidomimetic (20 μM) and growth factor (2 nM) for 20 min. Detergent lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-pTyr monoclonal antibody (mAb) 4G10 or anti-phospho-MAPK. Membranes were re-blotted with anti-actin to verify protein loading. Blots were quantified by densitometry.

In NIH3T3-TrkC cells, 6dh significantly blocked (40%) the level of TrkC-pTyr that was stimulated by NT-3 (Figure 4a). No significant effect was observed in NIH3T3-TrkA cells stimulated with NGF (Figure 4b) or in NIH3T3-IGF-1R cells stimulated with IGF-1 (Figure 4c). Together, these data indicate 6dh is a selective inhibitor of NT-3–mediated activation leading to TrkC phosphotyrosinylation.

The inhibition of TrkC-pTyr correlates with the inhibition of the phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Erk1,2 protein, which is a major signal transduction pathway activated by neurotrophin receptor. Mimic 6dh blocks the activation of MAPK by TrkC (70%) (Figure 4a) but not by TrkA or by IGF-1R (Figure 4b and c).

There are relatively few small molecule ligands for the neurotrophin receptors.8,20–26 One of the earliest, a compound we call D3 was designed to mimic putative β-turn hot-spots in the nerve growth factor (NGF).6,7,27 In vitro and in vivo tests on D3 indicate this is a partial TrkA agonist, that has no significant binding to the other Trk receptors. This compound shows promise for the treatment of stroke and glaucoma. Whereas similar compounds from our labs have been shown to be agonists or partial agonists for the TrkC receptor (the one that has greatest affinity for neurotrophin-3 {NT-3}),18,28 this paper demonstrates a molecule that contains not one but two β-turn mimics at an optimized separation can serve as a TrkC antagonist. The most active of the molecules 6 (ie 6dh, the one from 4d and 4h) contains two DKPs with side chains from Glu and Lys (EK); this mimics the sequence DEKQ corresponding to murine NGF and not NT-3 but the molecule was active on TrkC and not on TrkA. The 92 – 95 turn region of NT-3 (human or mouse) contains the ENNK motif. Consequently, it is possible that this compound mimics the i and i + 3 residues of this turn rather than the i + 1 and i + 2 regions. In summary, this peptidomimetic is a ligand of TrkC, and an antagonist of TrkC–NT-3 activity. Our findings further demonstrate that peptidomimetic molecules can be made to act specifically on certain Trk receptors. Finding a small, stable molecule with selective agonist/antagonistic activity may be useful as a therapeutic agent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (MH070040, GM076261), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A-1121) to KB, and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant 1192060 to HUS. TAMU/LBMS-Applications Laboratory provided mass spectrometric support. The NMR instrumentation in the Biomolecular NMR Laboratory at Texas A&M University was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (DBI-9970232) and the Texas A&M University System.

Abbreviations

- TrkC

Tropomysin receptor kinase C

- DKP

diketopiperazine

- EDCI

1-ethyl-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- NMM

N-methylmorpholine

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- IGF-1R

insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

- SFM

serum-free media

- NT-3

neurotrophin-3

- pTyr

phosphotyrosine

- Erk

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- NGF

nerve growth factor

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE. Details of the compound purities, procedure for syntheses of compounds 1–6, and characterization of representative dimers. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Skaper SD. The biology of neurotrophins, signalling pathways, and functional peptide mimetics of neurotrophins and their receptors. CNS & Neurological Disorders: Drug Targets. 2008;7:46–62. doi: 10.2174/187152708783885174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivanisevic L, Saragovi HU. The Neurotrophins. In: Kastin AJ, editor. Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 1407–1413. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollack SJ, Harper SJ. Small molecule Trk receptor agonists and other neurotrophic factor mimetics. Current Drug Targets: CNS & Neurological Disorders. 2002;1:59–80. doi: 10.2174/1568007023339490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman WJ, Greene LA. Neurotrophin signaling via Trks and p75. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:131–142. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y, Pattarawarapan M, Wang Z, Burgess K. Solid-phase SN2 macrocyclization reactions to form β-turn mimics. Org Lett. 1999;1:121–124. doi: 10.1021/ol990597r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng Y, Burgess K. Solid phase SNAr macrocyclizations to give turn-extended-turn peptidomimetics. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:3261–3272. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, Wang Z, Jin S, Burgess K. SNAr cyclizations to form cyclic peptidomimetics of β-turns. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10768–10769. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maliartchouk S, Feng Y, Ivanisevic L, Debeir T, Cuello AC, Burgess K, Saragovi HU. A designed peptidomimetic agonistic ligand of TrkA nerve growth factor receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brahimi F, Malakhov A, Lee HB, Pattarawarapan M, Ivanisevic L, Burgess K, Saragovi HU. A peptidomimetic of NT-3 acts as a TrkC antagonist. Peptides. 2009;30:1833–1839. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pattarawarapan M, Reyes S, Xia Z, Zaccaro MC, Saragovi HU, Burgess K. Selective formation of homo- and heterobivalent peptidomimetics. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3565–3567. doi: 10.1021/jm034103e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brahimi F, Liu J, Malakhov A, Chowdhury S, Purisima E, Ivanisevic L, Caron A, Burgess K, Saragovi H. Dimerization of a monovalent small molecule ligand changes a TrkA receptor agonist into an antagonist: Implications for conformational changes. 2010. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D, Brahimi F, Angell Y, Li YC, Moscowicz J, Saragovi HU, Burgess K. Bivalent peptidomimetic ligands of TrkC are biased agonists, selectively induce neuritogenesis, or potentiate neurotrophin-3 trophic signals. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:769–781. doi: 10.1021/cb9001415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angell Y, Chen D, Brahimi F, Saragovi HU, Burgess K. A combinatorial method for solution-phase synthesis of labeled bivalent β-turn mimics. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:556–565. doi: 10.1021/ja074717z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martins MB, Carvalho I. Diketopiperazines: Biological activity and synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:9923–9932. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerona-Navarro G, Bonache MA, Herranz R, Garcia-Lopez MT, Gonzalez-Muniz R. Entry to new conformationally constrained amino acids. First synthesis of 3-unsubstituted 4-alkyl-4-carboxy-2-azetidinone derivatives via an intramolecular Nα-Cα-cyclization strategy. J Org Chem. 2001;66:3538–3547. doi: 10.1021/jo015559b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohn Rhoden CR, Westermann B, Wessjohann LA. One-pot multicomponent synthesis of n-substituted tryptophan-derived diketopiperazines. Synthesis. 2008:2077–2082. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta A, Jaouhari R, Benson TJ, Douglas KT. Improved efficiency and selectivity in peptide synthesis: Use of triethylsilane as a carbocation scavenger in deprotection of tert-butyl esters and tert-butoxycarbonyl-protected sites. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:5441–5444. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaccaro MC, Lee BH, Pattarawarapan M, Xia Z, Caron A, L’ Heureux PJ, Bengio Y, Burgess K, Saragovi HU. Selective small molecule peptidomimetic ligands of TrkC and of TrkA receptors afford discrete or complete neurotrophic activities. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeSauteur L, Wei L, Gibbs B, Saragovi HU. Small peptide mimics of nerve growth factor bind TrkA receptors and affect biological responses. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6564–6569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeSauteur L, Cheung NKV, Lisbona R, Saragovi HU. Small molecule nerve growth factor analogs image receptors in vivo. Nature Biotech. 1996;14:1120–1122. doi: 10.1038/nbt0996-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maliartchouk S, Debeir T, Beglova N, Cuello A, Gehring K, Saragovi H. Genuine monovalent ligands of TrkA nerve growth factor receptors reveal a novel pharmacological mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9946–9956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo FM, Manthorpe M, Xie YM, Varon S. Synthetic NGF peptide derivatives prevent neuronal death via a p75 receptor-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:1–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970401)48:1<1::aid-jnr1>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, Tisi MA, Yeo TT, Longo FM. Nerve growth factors(NGF) loop 4 dimeric mimetics activate ERK and AKT and promote NGF-like neurotropic effects. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29868–29874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005071200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie Y, Longo FM. Neurotrophin small-molecule mimetics. Prog Brain Res. 2000;128:333–347. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(00)28030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Leary PD, Hughes RA. Design of potent peptide mimetics of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25738–25744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng Y, Wang Z, Jin S, Burgess K. Conformations of peptidomimetics formed by SNAr macrocyclizations: 13- to 16-membered ring systems. Chem Eur J. 1999;5:3273–3278. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattarawarapan M, Zaccaro MC, Saragovi U, Burgess K. New templates for synthesis of ring-fused C10 β-turn peptidomimetics leading to the first reported small-molecule mimic of neurotrophin-3. J Med Chem. 2002;45:4387–4390. doi: 10.1021/jm0255421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.