Abstract

Previous studies have speculated, based on indirect evidence, that the action potential at the transverse (t)-tubules is longer than at the surface membrane in mammalian ventricular cardiomyocytes. To date, no technique has enabled recording of electrical activity selectively at the t-tubules to directly examine this hypothesis. We used confocal line-scan imaging in conjunction with the fast response voltage-sensitive dyes ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus to resolve action potential-related changes in fractional dye fluorescence (ΔF/F) at the t-tubule and surface membranes of in situ mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes. Peak ΔF/F during action potential phase 0 depolarization averaged −21% for both dyes. The shape and time course of optical action potentials measured with the water-soluble ANNINE-6plus were indistinguishable from those of action potentials recorded with intracellular microelectrodes in the absence of the dye. In contrast, optical action potentials measured with the water-insoluble ANNINE-6 were significantly prolonged compared to the electrical recordings obtained from dye-free hearts, suggesting electrophysiological effects of ANNINE-6 and/or its solvents. With either dye, the kinetics of action potential-dependent changes in ΔF/F during repolarization were found to be similar at the t-tubular and surface membranes. This study provides what to our knowledge are the first direct measurements of t-tubule electrical activity in ventricular cardiomyocytes, which support the concept that action potential duration is uniform throughout the sarcolemma of individual cells.

Introduction

Previous studies have hypothesized, based on indirect evidence, that the electrical activity of the t-tubule is distinctly different from that of the surface membrane in mammalian ventricular cardiomyocytes (1–6). Experimental confirmation of this hypothesis has been hampered by the lack of a technique that allows direct assessment of the electrical activity of t-tubular membranes. This study documents a fluorescence-based approach to measuring transmembrane voltage changes with high spatio temporal resolution. Specifically, confocal laser scanning imaging in conjunction with fast response voltage-sensitive dyes is used to obtain high-fidelity action potential recordings on a subcellular scale in the Langendorff-perfused mouse heart.

Nonuniform distribution of ion current densities throughout the sarcolemmal membrane of cardiomyocytes can give rise to subcellular heterogeneity in transmembrane voltage. Tidball et al. (1) postulated that ion channels are differentially distributed between the surface and the t-tubular membranes. Using the whole-cell current-clamp technique, Brette and coworkers (5) measured transmembrane action potentials in control rat ventricular myocytes (i.e., from the t-tubule and surface sarcolemma) and in experimentally detubulated myocytes (i.e., from the surface sarcolemma only) to obtain an indirect estimate of the electrical behavior at the t-tubules. Detubulation resulted in marked action potential shortening, but did not alter resting membrane potential and action potential phase 0 amplitude. The decrease in action potential duration was ascribed to the loss of L-type Ca2+ current that predominately resides in the t-tubular membranes (5), whereas the contribution of other unequally distributed currents to membrane repolarization was deemed insignificant in these studies (6). Calculations based on these measurements predicted that the t-tubule action potential duration should be several times as long as that at the cell surface (5), when electrical coupling of the two membranes is disrupted. However, in a normal myocyte, the action potential duration was predicted to be uniform throughout the cell membrane because of the tight electrical coupling between the t-tubule and surface sarcolemmal membranes, i.e., the whole cell action potential represents the average of the action potentials generated by the electrically isolated membranes.

In addition to uneven distribution of current densities between the t-tubular and surface membranes, ion concentration gradients within the t-tubular lumen could also modify subcellular electrical activity. Previous studies (2–4) have shown that the t-tubular lumen forms a restricted extracellular space that allows ion depletion (e.g., Ca2+) and accumulation (e.g., K+), which can differentially alter the t-tubule action potential. In intact muscle, diffusion is also restricted in the intercellular clefts, and the extent to which differences in ionic composition in the intercellular cleft and the t-tubular lumen differentially regulate membrane potentials on a subcellular level is not known (7).

The use of electrical measurements, such as current-clamp recording, does not provide information on the spatial distribution of membrane potential within an individual cell. Many of the limits of spatial resolution can by overcome by optical imaging. For example, numerous studies have used voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes to monitor fast membrane potential changes at a subcellular scale in isolated neurons (8–10) or intact brain slices (11–14). In contrast, this technology has only been used rarely to map transmembrane potential distributions at a microscopic level in cardiac myocytes (15–18). Importantly, however, none of those studies attempted to systematically compare properties of action potentials generated at the t-tubules with those of action potentials generated at the outer sarcolemma.

In this study we describe the development and application of a fluorescence measurement technique that allows recording of transmembrane voltage changes with millisecond temporal resolution and spatial resolution from the multicellular to subcellular scale in the intact, Langendorff-perfused heart. This assay takes advantage of the recent synthesis of ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus, which belong to a new class of fast response voltage-sensitive dyes with markedly improved voltage discrimination (19,20). Using laser scanning confocal microscopy in line-scan mode, we have recorded action potential-dependent changes in fractional fluorescence intensity [ΔF/F] from surface and t-tubule membranes of individual cardiomyocytes within isolated perfused hearts loaded with either ANNINE dye. The accuracy of the fluorescence measurements to report changes in transmembrane voltage was verified with direct electrical recordings. Furthermore, we developed an off-line signal filtering algorithm to improve signal/noise ratios in single-trial optical recordings. We used an intact heart preparation instead of isolated cells for several reasons. First, cell injury associated with the isolation procedure is avoided. Second, it provides the ability to rapidly record data from a large number of cells. Third, the physiological contribution of restricted diffusion in the intercellular cleft to the subcellular voltage response is maintained. The results in this study support the notion that the shape and time course of transmembrane repolarization during the action potential are uniform throughout the sarcolemmal membrane of normal in situ cardiomyocytes.

Preliminary reports of this work were published previously in abstract form (21,22).

Materials and Methods

Heart preparation

Hearts from adult [C3Heb/FeJ × DBA/2J] F1 mice were used for all studies. After intraperitoneal injection of heparin (125 IU/kg body weight), the heart was excised, the ascending aorta was cannulated with a no. 18 cannula (length: 1 inch), and hearts were perfused in Langendorff mode. Perfusion was carried out at a constant pressure of 60–70 cm H2O and at room temperature (18–21°C) with oxygenated (100% O2) Tyrode's solution containing (in mmol/L) 134 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 11 D-glucose, and 2 CaCl2 (pH = 7.35 adjusted with 1 mol/l NaOH).

After dye loading (see below) the perfused heart was placed in a custom-made holding apparatus on the stage of an upright microscope with the anterior left ventricular epicardial surface up. To optimize the focal plane a 170-μm glass coverslip was pressed gently against the epicardial surface by adjusting the vertical distance between the coverglass and the aortic cannula. The holding apparatus was instrumented with stimulation and recording electrodes for electrical pacing and electrocardiographic monitoring, respectively. Hearts were stimulated with 2-ms square wave pulses with 1.5× threshold current amplitude. The stimuli were delivered by a computer-controlled constant-current isolator (Krannert Engineering, Indianapolis, IN). To monitor the efficacy of electrical pacing, a volume conducted electrocardiogram was continuously recorded. For a detailed description of the experimental set up see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material.

To uncouple contraction from excitation during imaging, cytochalasin D (50 μM; stock solution: 3.9 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in combination with ryanodine (1 μM; stock solution: 500 μM in distilled water; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) was added to the normal Tyrode's solution.

Dye loading

ANNINE-6 (Sensitive Farbstoffe, Munich, Germany) was dissolved in a solution of 20% (W/V) Pluronic F-127 DMSO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL and sonicated for 15 min at 9 W (Misonix Sonicator 3000, Misonix, Farmingdale, NY). The cannulated heart was perfused with the staining solution (dye stock solution diluted 1:100 in oxygenated Tyrode's solution containing 50 mM butanedione monoxime [BDM]) at a pressure of 60 cm H2O and a temperature of 36°C. After a 10-min loading period, perfusion was continued with dye-free Tyrode's solution for additional 20 min before imaging was started.

ANNINE-6plus (Sensitive Farbstoffe, Munich, Germany), a water soluble derivative of ANNINE-6 with identical spectral properties and voltage responsitivity (20), was dissolved in deionized water at a concentration of 0.575 mg/mL. Aliquots of the stock solution were diluted 1:200 in oxygenated, normal Tyrode's solution supplemented with 50 mM BDM. Dye loading was carried out as described for ANNINE-6, except that room temperature was used.

Imaging

All experiments were carried out at room temperature. For imaging we used a laser scanning upright microscope (Zeiss LSM510 Meta; Carl Zeiss Thornwood, NY) with Ar-ion laser excitation (488 nm). The heart was imaged through a Zeiss C-Apo 40× 1.2 NA water-immersion lens equipped with an adjustable collar. The excitation light was directed onto the specimen via the main dichroic beam splitter (HFT 488, a 488 nm reflector). The power of the incident laser light ranged from 150 to 300 μW at 488 nm. The emitted light was split by a dichroic mirror (NFT 545, a 545 nm long pass filter). The reflected light passed through a band-pass filter (500–550 nm), whereas the passing light was filtered by a long-pass filter (>560 nm). Short- and long-wave fluorescence light was collected simultaneously by two independent photomultipliers. Under the imaging conditions used, membrane depolarization caused a decrease in short- and long-wave fluorescence of the two ANNINE dyes. The detection pinhole radius was set to 957 nm (3.8 Airy units), providing an axial (z) resolution of 0.82 μm and lateral (x-y) resolution of 0.25 μm, as measured at full width at half maximum of calculated point spread functions (Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, Netherlands).

To optically detect action potentials, the unidirectional line-scanning mode of the scanning system was used. Line-scans were obtained from the surface membrane or across multiple t-tubules of in situ cardiomyocytes (see Fig. 3). Each scan line encompassed 128 pixels at a nominal pixel size of 0.05–0.3 μm, integrating for 3.20 or 2.56 μs (the shortest integration time compatible with a 128-pixel scan line) at each pixel, corresponding to line repetition rates of 1,042 or 1,302 lines/s, or temporal resolutions of ∼1 ms and ∼0.8 ms, respectively. During line-scan imaging we applied electrical stimuli to the right ventricular epicardial surface at 3 Hz, giving rise to action potential-related changes in dye fluorescence across the regions scanned. Line-scan images typically consisted of 8,000 to 10,000 lines, depending on the line repetition rate. Fluorescence intensities were recorded with 12-bit resolution. All recordings were obtained from the anterior left ventricular epicardium.

Figure 3.

Confocal line-scan imaging of voltage changes across the outer sarcolemma and t-tubule membrane of in situ cardiomyocytes. (A) Frame-mode and line-scan confocal images obtained from Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts loaded with ANNINE-6 (left) or ANNINE-6plus (right). Images were acquired during electrical point stimulation at 3 Hz in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine to dissociate contraction from excitation. White lines denote positions of the line-scan mode data acquisitions along end-to-end (a and d) and side-to-side (b and e) junctions between juxtaposed cardiomyocytes, and across multiple t-tubules (c and f) within single cardiomyocytes. Line-scan images (A, a–f) show 1-s segments of each of the 8.64-s long line-scan image acquisitions. Small letters next to the line-scan images refer to the scan regions delineated in the frame-mode images. Green scale bars = 8 μm. (B) Superimposed time plots of normalized fractional changes in dye fluorescence [ΔF/F0(t)] for the three recording sites per dye as indicated. Tracings were digitally filtered as outlined in the Appendix. (C) Superimposed tracings of the ensemble average of all 25 action potential-induced fluorescence transients per line-scan image for each of the three recording sites. (D) Bar graphs comparing properties of action potential-induced fluorescence changes in t-tubule and surface membranes in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine. (Left panel) Peak ΔF/F0 during action potential phase 0 depolarization. (Right panel) Action potential durations at various time points of repolarization. Values are mean ± 1 SD from 84 and 45 line-scans obtained in eight ANNINE-6- and four ANNINE-6plus-loaded mouse hearts, respectively. E, end-to-end membrane junction; S, side-to-side membrane junction; T, t-tubular membranes. ∗p < 0.025 versus peak ΔF/F0 at side-to-side membrane junctions and t-tubular membranes of the same dye (paired t-test). †p < 0.05 versus ANNINE-6 (t-test). Peak ΔF/F0 and action potential durations were measured from the ensemble average traces.

Image processing

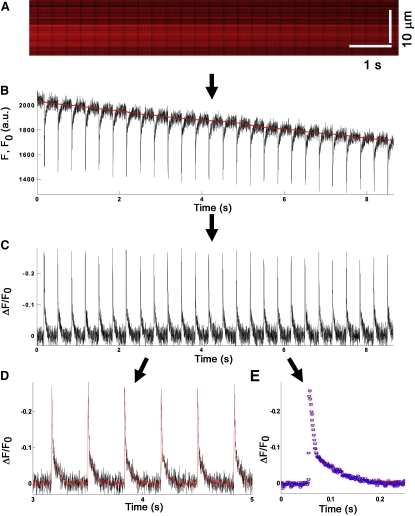

To resolve the time course of action potential-related changes in dye fluorescence in the line-scan images, we applied the following off-line processing steps (see also Fig. 2):

-

1.

Calculation of the average signal intensity of each successive line in a line-scan image to obtain the time course of the spatial averaged fluorescence, F(t). Thus, each point in the F(t) trace represents the average of 128 pixels sampled along an individual scan line at a particular time point;

-

2.

Estimation of the baseline trace [F0(t)] using a low-pass filter and a moving average filter;

-

3.

Determination of the time course of normalized fractional fluorescence changes [ΔF/F0(t)], where ΔF is F(t) − F0(t);

-

4.

Alignment of the onset of phase 0 depolarizations of all optical action potentials in a ΔF/F0(t) trace and subsequent calculation of the ensemble average; and

-

5.

Filtering the ΔF/F0(t) trace to increase the signal/noise ratio of single-trial optical action potential recordings.

Figure 2.

Scheme for off-line signal processing. Graphic representation of the off-line signal processing steps that were used to correct for dye bleaching-induced baseline drift, to calculate relative fluorescence changes [ΔF/F] and to improve the signal/noise ratio. (A) Line-scan image of action potential-related changes in ANNINE-6 fluorescence that was obtained from an end-to-end junctional membrane of two juxtaposed cardiomyocytes in situ during pacing at 3 Hz. (B) By averaging 128 pixels in each line of the line-scan image in the vertical direction, the time course of the spatial averaged fluorescence [F(t)] was determined. To obtain the time course of normalized fractional changes in dye fluorescence [ΔF/F0(t)] the baseline [F0(t)] was estimated (denoted by the red solid line) using a combination of a 250-sample moving averaging filter and a 4th-order Butterworth low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 3 Hz. (C) Rendition of ΔF = F(t) − F0(t) normalized to F0(t). (D) To increase the SNR of single-trial recordings, plots of ΔF/F0(t) were processed with a custom-designed optimal filtering algorithm. A filtered 2-s segment from the trace in C is shown (red line). See Appendix A for more detailed description of the optimal filtering algorithm. (E) Recordings of normalized changes in fractional fluorescence occurring during each consecutive action potential in a line-scan image were aligned using both cross-correlation analysis and pacing cycle, and the ensemble average was calculated (red symbols). A single action potential that was obtained by processing the trace in C with the optimal filtering algorithm was superimposed (blue symbols).

Image processing was carried out using software written in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) and implemented on a Dell computer (Dell Computers, Round Rock, TX). Detailed descriptions of the processing algorithms are given in Appendix A.

Peak signal/noise ratio (SNR) was defined as SNR = Spp/Nrms, where Spp is the peak-to-peak amplitude of the optical action potential (i.e., maximum ΔF/F0(t) during action potential upstroke minus resting ΔF/F0(t)), and Nrms is the root mean-squared noise recorded during the 50-ms segment preceding the upstroke of the optical action potential. Voltage resolution was calculated from noise levels relative to the electrically measured action potential phase 0 amplitude (APA), i.e., voltage resolution = APA/SNR mV. Voltage sensitivity was defined as the relative change of the fluorescence intensity in response to the voltage change during the action potential upstroke, i.e., Sv = (ΔF/F)/APA %/mV. Action potential durations (APD) in electrical recordings were determined from measurements of the time point of maximum upstroke velocity (dV/dt)max minus the time point at which the downstroke recovered to 30%, 50%, and 70% back to baseline, i.e., APD30, APD50, and APD70.

Intracellular microelectrode recordings of transmembrane action potentials

Glass pipettes (10–20 MΩ) filled with 3 M KCl solution were mounted on a micromanipulator and used to impale cardiomyocytes in the anterior left ventricular epicardium approximately midway between the apex and the base of the Langendorff-perfused heart. The electrical signal recorded with the glass microelectrode was amplified (Dagan Instruments, Minneapolis, MN), and the amplifier's signal output was fed to a 16-bit DAQ device (National Instruments, Austin, TX), sampled at 20 kHz and stored in computer hard disk drive for off-line analysis.

Statistical analysis

Results in this study were expressed as mean ± 1 SD. Statistical comparisons were made using single-factor ANOVA or Student's t-test. A value for p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Imaging action potential-related fluorescence changes on a subcellular scale in Langendorff-perfused mouse heart

An important prerequisite to using the ANNINE-6 dyes as voltage-sensing fluorophores is to show that they specifically and stably anchor at the outer membrane compartments of interest, which in the case of cardiomyocytes are the outer sarcolemmal and t-tubular membranes. A representative confocal section taken from a Langendorff-perfused mouse heart 150 min after loading with ANNINE-6 is shown in Fig. 1 A (left panel). The image was acquired during continuous electrical pacing via point stimulation at the right ventricular epicardium in the presence of cytochalasin D and ryanodine. Thick lines of high fluorescence intensity correspond to ANNINE-6 staining of surface membranes in adjacent cardiomyocytes. High magnification views (Fig. 1 A, middle and right panels) also show the presence of thin, parallel lines of high fluorescence intensity, reflecting dye accumulation in the t-tubular membranes. T-tubules are invaginations of the outer membrane, which flank each sarcomere at the level of I-bands, giving rise to the regular spacing between consecutive lines (23). Further, fluorescence is not discernible in the myoplasm, the nucleoplasm, or internal membrane compartments (i.e., intracellular organelles, nuclear envelope), supporting the notion that ANNINE-6 exclusively binds to the surface and t-tubular membranes. In addition, the intensity and spatial profile of ANNINE-6 fluorescence remained largely unaltered for up to 3 h after dye loading (the longest time interval tested in our experiments), thus showing that the dye is effectively retained in the outer membrane compartments. Identical observations were made after exposure of Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts to ANNINE-6plus.

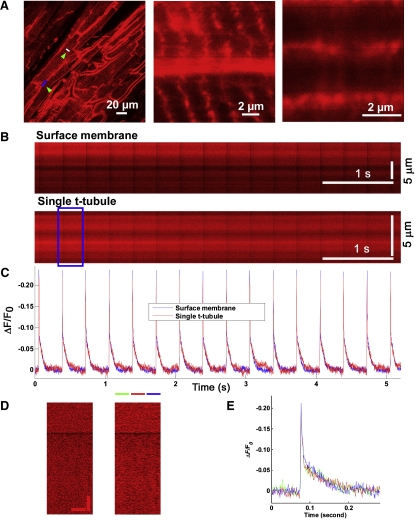

Figure 1.

Confocal imaging of the cardiomyocyte action potential in Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine. (A) Full-frame mode (XY) image obtained from a heart loaded with ANNINE-6. The green bar demarks the position of line-scan mode data acquisition along the end-to-end membrane junction between two neighboring cardiomyocytes. The heart was electrically paced at 3 Hz via right epicardial point stimulation. The image was acquired 150 min after dye loading. The middle panel shows a magnified view of the blue boxed region in the full frame-mode image. Sharp lines (black arrows in the middle panel) correspond to action potential-related decreases in ANNINE-6 fluorescence. The right panel shows magnified views of ANNINE-6 fluorescence distribution around cardiomyocyte nuclei. (B) Line-scan (X-t) image of the region in A demarked by the green line. The image is composed of 9000 horizontally stacked line-scans. Each scan line encompassed 128 pixels along a 16.84-μm line integrating for 3.2 μs at each pixel. Line-scan repetition rate was 1024 Hz. Lower trace shows the volume conducted electrocardiogram that was recorded during image acquisition. Asterisks indicate electrical stimulation artifacts. (C) Expanded record of changes in ANNINE-6 fluorescence during the cardiomyocyte action potential. The left panel shows the unprocessed line-scan image of fluorescence changes during the action potential boxed in B. Normalization of the fluorescence signal (F/F0) removed the nonuniformity in the signal (right panel). Scale bar = 50 ms vertically, 5 μm horizontally. (D) Time course of spatial averaged ANNINE-6 fluorescence from the normalized line-scan image in C.

Magnified views of the boxed region (blue) in the left panel of Fig. 1 A also showed the presence of periodic fluorescence decreases occurring as sharp lines across the width of the region scanned (Fig. 1 A, middle panel). Transient membrane depolarizations have been shown previously to be accompanied by decreases in ANNINE-6 fluorescence intensity above 560 nm, supporting the idea that the intermittent reductions in ANNINE-6 fluorescence reflect cardiomyocyte membrane depolarizations during stimulated action potentials. To further characterize the time course and magnitude of action potential-dependent changes in dye fluorescence, we recorded fluorescence signals in the line-scan mode simultaneously with a volume conducted electrocardiogram. The scan line was positioned along an end-to-end membrane junction between two neighboring cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1 A, green line). The stacked line-scan image (Fig. 1 B, upper panel) shows periodic transient decreases in fluorescence that coincide with the paced QRS complexes (Fig. 1 B, lower panel), indicating that fluorescence changes arise in response to stimulated action potentials. In the absence of cell membrane movement, the brief negative fluorescence changes reflect changes in transmembrane voltage during the action potential. In addition to action potential-associated, rapid transient decreases in the fluorescence signal we also observed a gradual decline in baseline fluorescence intensity that continued throughout image acquisition and resulted from photobleaching of the fluorescent dye. The left panel of Fig. 1 C shows the expanded fluorescence record during the course of an action potential from the line-scan segment delimited by the rectangle in Fig. 1 B. Normalizing the intensity of each pixel to its respective baseline value removed the marked spatial heterogeneity in signal strength both at baseline and during the action potential (right panel of Fig. 1 C), suggesting that it resulted from differences in dye distribution rather than from nonuniformities in transmembrane voltage changes across the scan line. We also quantified the time course of the change in normalized fluorescence intensity across the scan line and plotted the intensity against time. The result is shown in Fig. 1 D. The trace reflects the characteristic shape of the transmembrane action potential previously measured in left epicardial myocytes from mice (24), supporting the notion that the optical signal reflects the change in transmembrane voltage during a stimulated action potential.

Normalized fluorescence signals

We used a multistep approach to derive action potentials from the optical recordings, including correction for dye bleaching, calculation of the relative fluorescence change [ΔF/F0(t)], and noise reduction (see Image processing in the Materials and Methods). A scheme describing the various levels of signal processing is depicted in Fig. 2, using the line-scan image of action potential-dependent changes in ANNINE-6 fluorescence shown in Fig. 1 B as an example. The line-scan image is composed of 9000 line-scans that were obtained with 1 ms resolution along a junctional membrane segment 16.84 μm long, integrating for 3.2 μs at each scanning point (Fig. 2 A). By averaging all pixels in each line of the line-scan image in the vertical direction, the time course of the spatial averaged fluorescence [F(t)] was obtained (Fig. 2 B). To correct for the photobleaching-induced baseline drift, the relative changes in fluorescence intensity [ΔF(t)] were normalized to the baseline fluorescence [F0(t)] and subsequently plotted against time. The resulting single-trial trace (Fig. 2 C) shows a train of 26 consecutive action potentials in response to electrical point stimulation delivered at 3 Hz over 10 s. The ensemble average of all 26 optical responses from the single-trial data shown in Fig. 2 C exhibited the characteristic shape of the mouse left ventricular epicardial action potential (Fig. 2 E, red symbols) (24). It also exemplifies the large magnitude of the peak ΔF/F0(t) (∼−25%) and the high peak SNR (∼60) that were typically achieved with this assay (Fig. 2 E, red symbols). Although ensemble averaging markedly improved the SNR compared to single-trial data, this approach is not suited to reduce signal noise in single-trial traces under nonsteady state conditions (e.g., arrhythmia), where detection of beat-to-beat variations is critical. Accordingly, an optimal filtering algorithm was developed that was capable of improving the SNR in single-trial traces without noticeably distorting the time course and shape of optically recorded changes in transmembrane voltage (see Appendix A). A typical result is shown in Fig. 2 D. The filtered trace (red line) faithfully tracks the raw data trace. Optimal filtering increased peak SNR by ∼5-fold compared to the unfiltered raw data. The degree of noise reduction in single-trial traces was similar to that of the ensemble average, as superimposition of the respective traces shows (Fig. 2 E). Application of the filtering algorithm to single-trial traces exhibiting pronounced beat-to-beat variations in the shape of the optical action potential similarly resulted in significant noise reduction while retaining the signal characteristics (see Fig. S2). Collectively, these results provided a proof-of-principle for the ability of our assay to resolve action potential-dependent changes in fluorescence intensity from a few micron-long cardiomyocyte membrane patches in the isolated perfused mouse heart.

Comparison of optical action potentials at the t-tubule and surface sarcolemmal membranes

A previous study showed that the density of L-type calcium current and inward Na+/Ca2+ exchange current are markedly higher in the t-tubule than in the surface membrane of ventricular cardiomyocytes, whereas K+ currents exhibit a more even subcellular distribution (5,6). The uneven distribution of inward currents between the t-tubule and surface membranes has given rise to the hypothesis that the t-tubule action potential duration is significantly longer than at the cell surface. We sought to examine the ability of our imaging approach to provide direct measurements of the t-tubule action potential. Fig. 3 shows representative results that were obtained from ANNINE-6- or ANNINE-6plus-loaded hearts in the presence of the excitation-contraction uncouplers cytochalasin D and ryanodine. The scan line was positioned along side-to-side and end-to-end membrane junctions between juxtaposed cardiomyocytes, or across multiple t-tubules within a single cell (Fig. 3 A). Line-scan images were obtained sequentially from all three regions. Single-trial traces of the optical action potentials (Fig. 3 B) and their respective ensemble averages (Fig. 3 C) show peak fractional fluorescence changes exceeding 20% at all three recording sites with either dye. The kinetics of the change in normalized fluorescence from the three regions were superimposable, supporting the idea that action potentials at the t-tubule and cell surface exhibit a very similar time course under the experimental conditions studied. Quantitative comparison of action potential duration measurements at the surface membranes (end-to-end and side-to-side junctions) and t-tubules in eight and four hearts stained with ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus, respectively, confirmed that the time course of fluorescence recovery (that is indicative of transmembrane repolarization) was indistinguishable between the different recording sites for either dye (Fig. 3 D, right panel). The mean peak ΔF/F0 measured with either dye at the end-to-end membrane junction was significantly larger than that at the side-to-side junction or t-tubules (Fig. 3 D, left panel). We also found that the late repolarization in optical action potentials (APD70) was significantly prolonged in hearts stained with ANNINE-6 compared to ANNINE-6plus-stained hearts (Fig. 3 D, right panel).

Line-scans that traversed multiple t-tubules also contained pixels that were from inner (e.g., mitochondrial) membrane compartments. Importantly, however, the kinetics of the change in normalized fluorescence in line-scans that were positioned along single t-tubules were indistinguishable from those recorded at the surface membrane (Fig. 4, A–C). Thus, action potential-dependent changes in ANNINE fluorescence intensity seem to originate solely in the outer membranes of cardiomyocytes.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the optical action potential at a single t-tubule and at the surface membrane. (A) Frame-mode image taken from a heart loaded with ANNINE-6plus. The blue and white line denote positions of the line-scan mode data acquisitions at a side-to-side junction and along a single t-tubule, respectively. Middle and right panel show zoom-in views of the regions around the labeled side-to-side and t-tubule membrane positions. The thick red line in the middle panel represents ANNINE-6plus fluorescence originating from outer sarcolemmal membranes of two adjacent cardiomyocytes, whereas the red lines perpendicular to the thick line are t-tubules of either myocyte. (B) Line-scan images that were obtained by repetitive scanning at a rate of 1,024 lines/s along the white lines in A. (C) Overlay of filtered ΔF/F0(t) traces for the two scan positions demarked in A. (D) Expanded record of changes in ANNINE-6plus fluorescence during the action potential. The left panel shows the normalized (F/F0) line-scan image during the action potential boxed in B. Image in the right panel was low-pass filtered to give a spatial resolution of 0.2 μm, and the contrast enhanced. Scale bars = 50 ms vertically, 2 μm horizontally. (E) Kinetic comparison of the normalized fluorescence signal from the three regions (colored bars) indicated in C. Each region is 2 μm wide. Note the similarity in the time course of the action potential-related fluorescence changes from the three regions.

Line-scan images as those shown in Fig. 4 B provide the unique opportunity to obtain detailed information on the distribution of voltage changes along single t-tubules during the course of an action potential. Fig. 4 D shows a normalized fluorescence record during a single stimulated action potential. As can be seen, the fluorescence intensity decreased rapidly and synchronously across the width of the region scanned, implying that membrane voltage changes during action potential phase 0 depolarization were spatially uniform within the individual tubule. Low-pass filtering to give a spatial resolution of 0.2 μm in combination with contrast enhancement further accentuated the spatial uniformity of depolarization during the action potential upstroke (Fig. 4 D, right panel). Finally, to examine whether the time course of the t-tubular fluorescence response changes with increasing distance from the surface membrane, the intensity of the three regions demarked by colored bars in Fig. 4 D was plotted against time (Fig. 4 E). The fluorescence ratio of all three regions exhibited a similar time course, indicating that membrane voltage changes during an action potential are spatially uniform within the t-tubular network, at least within the resolution of our system.

Collectively, our findings show the capability of our assay to resolve action potential-related changes in fluorescence intensity from t-tubules of individual cardiomyocytes within the isolated perfused mouse heart. Further, our results support the notion that the shape and time course of the action potential are spatially uniform within individual in situ cardiomyocytes under the experimental conditions studied and within the resolution of our imaging system.

Correlation of electrical and optical action potentials

We next sought to directly examine whether the configuration of the action potential recorded optically is a true representation of the electrical response of in situ cardiomyocytes located in the left anterior epicardium. We chose ANNINE-6plus for these studies, because its application does not require the addition of organic solvents and/or surfactants, which by themselves may exhibit confounding electrophysiological effects. Fig. 5 illustrates measurements of action potentials using intracellular microelectrode impalement (Fig. 5 A) and optical detection with ANNINE-6plus (Fig. 5 B). The microelectrode signal was sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 10 kHz, whereas the optical action potential was recorded from an end-to-end junction at 1,042 Hz and filtered using the optimal filtering algorithm (see Appendix A). The shape of the optical action potential and the rate of fluorescence recovery suggested that the dye closely follows the membrane voltage changes during phases 1–4 of the cardiomyocyte action potential. Quantitative comparisons confirmed that the mean action potential durations measured at various time points during repolarization were not significantly different for the optical and microelectrode technique (Fig. 5 C). Optical and electrical signals during phase 0 depolarization only partially overlapped (Fig. 5 D). The low sampling rate of the optical recordings in relation to that of the electrical recordings prevented a detailed quantitative comparison. To further characterize the bandwidth characteristics of our imaging approach, we compared the frequency content of action potentials recorded optically to that of action potentials recorded electrically. Using a discrete Fourier transform, we obtained the power spectral density distributions for the electrical and optical signal shown in Fig. 5, A and B, respectively, over frequencies ranging from 0 to the Nyquist frequency (= half the sampling frequency) of either recording method. Log-log plots of the resulting power spectral density curves are shown in Fig. 5 E. As can be seen, the entire power spectrum of the optical signal (spanning a frequency range from 0 to 521 Hz) overlaps with the corresponding portion of the power spectral density distribution for the electrical signal. Integration of the power spectral density distribution for the electrical signal showed that 99.7% of the total energy (i.e., the energy across the frequency range from 0 to 10 kHz) is contained between 0 and 200 Hz. Thus, the microelectrode signal is essentially band-limited to 200 Hz and represents an upper limit on the frequency content of the optical action potential. According to the Nyquist criterion, sampling rates used in the optical action potential recordings are sufficient to track voltage changes typically occurring during the cardiac action potential. The single peak at 2.015 kHz reflects the phase 0 upstroke and was clearly outside the recording bandwidth of the optical technique. These results indicate that ANNINE-6plus tracks transmembrane voltage changes throughout repolarization of the action potential under the experimental conditions studied.

Figure 5.

Kinetic comparison of the optical and electrical signals. (A) Transmembrane action potentials recorded with an intracellular microelectrode from the anterior left ventricular epicardium of a Langendorff-perfused mouse heart during electrical point stimulation at 3 Hz. Arrows indicate stimulation artifacts. The recording was obtained in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine. The signal was low-pass filtered at 10 kHz and sampled at 20 kHz. (B) Plot of action potential-induced fractional fluorescence changes [ΔF/F0(t)]. The fluorescence signal was resolved from a confocal line-scan image that was obtained by repeatedly scanning along an end-to-end junction at a rate of 1042 Hz. The fluorescence signal was processed as described in the Appendix A. (C) Comparison of action potential duration in optical and electrical recordings. Intracellular microelectrode recordings were carried out in hearts loaded with ANNINE-6plus. Values are mean ± 1 SD from 45 optical and 124 electrical measurements that were obtained in four and five hearts, respectively, in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine. Optical recordings from all three outer membrane compartments were included. No statistically significant differences were found (t-test; p > 0.05). (D) Overlay of the initial portion of an optical and electrical action potential at expanded timescale. (E) Power spectral density distributions of the electrical and optical signal in A and B, respectively. Spectra were generated over frequencies ranging from 0 to the Nyquist frequency of the respective recording method (521 Hz for the optical and 10 kHz for the microelectrode technique). The spike at 2015 Hz represents the phase 0 depolarization of the transmembrane action potentials. Inset shows the power spectrum over the frequency range from 2010 to 2020 Hz.

The voltage sensitivity of ANNINE-6plus was calculated as the ratio of the average peak ΔF/F0 for all three recording sites (−21.4 ± 2.3%) and the average phase 0 action potential amplitude measured with microelectrode technique in the presence of ANNINE-6plus (86 ± 7.9 mV), yielding an estimate of −0.29 ± 0.01%/mV. The voltage resolution in ensemble average recordings with 1 ms temporal resolution was estimated to be 1.5 ± 0.9 mV.

To verify that the ANNINE-6plus fluorescence signal varies linearly with transmembrane voltage, we plotted the fluorescence changes (expressed in −ΔF/F0) occurring during action potential repolarization as a function of the magnitude of the transmembrane voltage change relative to the resting membrane potential. The result is shown in Fig. 6 A. The linear regression fitted to the data shows a strong correlation (R = 0.994; p < 0.0001) between the fractional fluorescence change and voltage, indicating a linear dye response over a range of transmembrane voltages occurring under the experimental conditions studied. Finally, we validated the ability of the potentiometric dye to report dynamic changes in action potential shape and time course. Fig. 6 B shows action potential-induced changes in ANNINE-6plus fluorescence during spontaneous, irregular electrical activity of the heart. As can be seen, action potentials with brief coupling intervals (e.g., the fourth and fifth action potential) exhibited a significantly shorter duration at late repolarization than action potentials with long coupling intervals (e.g., the second and ninth action potential). This behavior is in accordance with electrical restitution properties of mouse left ventricular epicardial myocytes in situ described previously (25) and shows the ability of the dye to report dynamic changes in action potential shape and duration.

Figure 6.

Properties of ANNINE-6plus. (A) Voltage dependence of ANNINE-6plus fluorescence. ANNINE-6plus fluorescence changes (expressed in [− ΔF/F0]) were plotted as a function of the magnitude of the transmembrane voltage change [ΔV] relative to the resting membrane potential. Data points were derived from the ensemble averages of the tracings shown in A and B of Fig. 5. Only data points during the action potential repolarization were included in the analysis. The line is a linear regression of the data (slope: 0.0217; y axis intercept: 0.0092; R = 0.994). (B) Effect of changes in coupling interval on optical action potential duration. Plot of action potential-induced fluorescence changes [F(t)] that were recorded during spontaneous, irregular electrical activity of a Langendorff-perfused mouse heart loaded with ANNINE-6plus. The fluorescence signal was resolved from a confocal line-scan image that was obtained by repeatedly scanning along an end-to-end junction at a rate of 1042 Hz. The recording was obtained in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine.

A previous study by Kuhm et al. (19) showed that the use of longer excitation wavelengths increases the voltage sensitivity of ANNINE dyes. Accordingly, we examined whether the voltage dependence of the fluorescence signal becomes more sensitive with an increase in excitation wavelength in hearts loaded with ANNINE-6, by imaging along the same membrane patch using the long and short wavelength light alternately. The average peak fractional fluorescence change during action potential phase 0 depolarization was similar at either excitation wavelength (−16.8 ± 3.0% and −18.3 ± 5.3% at 488 nm and 514 nm, respectively; p > 0.05), whereas the peak SNR in ensemble average traces obtained with the longer excitation wavelength was significantly smaller than that obtained with the short wavelength (26.7 ± 6.0 vs. 42.2 ± 12.5; p = 0.01; paired t-test; 15 paired measurements in two hearts). In addition to examining the effect of increasing excitation wavelength in single-photon excitation mode, we also tested whether two-photon excitation improved voltage sensitivity of ANNINE dyes, as had been reported previously (19). Experiments at 960 nm (the maximal obtainable wavelength in our system) did not yield detectable fluorescence changes in response to action potentials using low incident laser power, whereas higher light intensities resulted in extensive structural damage of the illuminated tissue within a few seconds.

One major concern with all voltage-sensitive dyes is their possible pharmacological effect on the biological specimen (26–28). Accordingly, we sought to examine whether ANNINE-6plus itself (in the absence of laser illumination) exerts electrophysiological effects at the level of individual cardiomyocytes in intact hearts. Transmembrane action potentials were recorded in Langendorff-perfused hearts in the absence and presence, respectively, of ANNINE-6plus (28 μg applied over 10 min), using the microelectrode technique. The perfusing Tyrode's solution also contained 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine. Recordings were repeated every 5 min over 2 h after completion of dye loading. We found that the dye did not significantly alter resting membrane potential or the time course of repolarization (Table 1). However, the average magnitude of the maximal upstroke velocity and the depolarization during phase 0 of the action potential was significantly larger in ANNINE-6plus-loaded hearts compared to dye-free hearts.

Table 1.

Comparison of transmembrane action potential properties of in situ ventricular cardiomyocytes in the presence and absence of ANNINE-6plus

| Without ANNINE-6plus | With ANNINE-6plus | |

|---|---|---|

| APD30, ms | 4.7 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 0.9 |

| APD50, ms | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 8.0 ± 1.3 |

| APD70, ms | 14.3 ± 4.2 | 14.4 ± 3.2 |

| RMP, mV | −77.5 ± 2.6 | −77.0 ± 2.2 |

| APA, mV | 80.6 ± 9.2 | 86.0 ± 7.9∗ |

| (dV/dt)max, V/s | 54 ± 22 | 64 ± 21.9∗ |

Values are mean ± 1 SD from 110 (without dye) and 124 (with dye) recordings that were obtained in five hearts for each group in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine. Stimulation rate was 3 Hz.

Indicates significant difference (p < 0.001; t-test) versus Without ANNINE-6plus. APD30, APD50, APD70: action potential duration at 30%, 50%, and 70% repolarization; RMP, resting membrane potential; APA, phase 0 action potential amplitude; (dV/dt)max, maximal phase 0 upstroke velocity.

Photostability of ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus

Plots of the spatial average fluorescence against time [F(t)] typically showed a decay of the action potential-related signal amplitude and a concomitant decrease in baseline fluorescence intensity. Fig. 7 A (upper panels; for another example see also Fig. 2 B) shows examples for the case of ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus. Conversion of absolute to relative fluorescence intensities for each time point in the F(t) traces readily eliminated the decay in signal amplitude (Fig. 7 A, lower panels), suggesting that it was caused by bleaching of the dye molecules rather than by an actual decrease in action potential amplitude resulting from phototoxic effects. Quantitative comparisons of the average time course of photobleaching (Fig. 7 B, upper panels) with that of the average fractional changes in signal amplitude (Fig. 7 B, lower panels) from 20 recordings for either dye confirmed the absence of a significant decrease in relative signal amplitude despite the decay in baseline fluorescence. For the analyses we included line-scan images that were obtained using magnitudes of incident laser power that were representative for our experiments. The results indicate that cumulative illumination energies typically encountered during seconds long line-scan recordings did not noticeably alter the cardiomyocyte membrane response. This view is further supported by the observation that the time course of repolarization measured optically in ANNINE-6plus loaded hearts matched the electrical signal recorded in the presence of the unexcited dye.

Figure 7.

Comparison between the time course of dye bleaching and the time course of the peak amplitude of the fractional fluorescence change [ΔF/F] during confocal line-scan imaging. (A) Time course of total fluorescence [F(t)] and fractional fluorescence change [ΔF/F0(t)] for the first and last three action potentials of 8.64-s long line-scan recordings obtained with ANNINE-6 (left panels) and ANNINE-6plus (right panels). (B) Decay of F(t) normalized to the zero time point and decrease in peak ΔF/F0(t) for ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus. Values are mean ± 1 SD from 20 independent line-scans for each dye. All line-scan images were acquired in the presence of 50 μM cytochalasin D and 1 μM ryanodine.

Discussion

Major findings

In this study, we have shown that laser confocal microscopy in line-scan mode in combination with the fast response voltage-sensitive dyes ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus is capable of monitoring transmembrane voltage changes on a subcellular scale from in situ cardiomyocytes with ∼1 ms temporal resolution. The optical signal varies linearly with voltage and closely reported changes in transmembrane voltage during the repolarization phases. Fast changes during the action potential upstroke escaped the bandwidth of the imaging system. We were able to selectively record the electrical activity of the t-tubule or surface membranes of individual cardiomyocytes in intact, Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Using either dye, the time course and shape of the t-tubule action potential were found to be indistinguishable from those generated at the surface membrane. The results presented in this study support the idea that transmembrane voltage changes during action potential repolarization occur uniformly throughout the sarcolemmal membrane of normal in situ ventricular cardiomyocytes.

Properties of ANNINE-6 and ANNINE-6plus in isolated perfused mouse heart

The voltage sensitivity of ANNINE-6plus in heart (−0.29 ± 0.01%/mV) is in very good agreement with that measured in Retzius cells of the leech at 488 nm excitation (20), and also in excellent agreement with the voltage-sensitivity of ANNINE-6 previously determined in Aplysia neurons (11) and HEK293 cells using the same excitation wavelength (19). Thus, our results extend the previous observation that the cell-type does not influence the magnitude of the voltage sensitivity of ANNINE dyes (19). We further found a linear response of ANNINE-6plus fluorescence with changes in transmembrane voltage over a range encountered in our study, and validated the ability of this dye to report alterations in action potential duration. Because we did not carry out electrical measurements of transmembrane action potentials in the presence of ANNINE-6, we are unable to quantitatively compare its voltage sensitivity in heart with that in other cell- or tissue-types.

One major concern with the use of voltage sensitive dyes is their potential phototoxicity (26,28,29). Although illumination energies that were used during seconds-long line-scan image acquisitions were typically associated with photobleaching of the ANNINE dyes, our findings indicate that these energy levels did not cause overt photodynamic damage. Thus, rapid photobleaching and the concomitant decrease in SNR, rather than photodamage, limit the duration of line-scan data acquisition under our imaging conditions.

We did not find evidence for transfer of ANNINE dyes into the cytoplasm of in situ cardiomyocytes. Confocal sections obtained from ANNINE-loaded hearts revealed lack of fluorescence signals in the membranes of cardiomyocyte nuclei or membranes of internal organelles up to three hours after dye loading. Thus, nonspecific background staining is low, resulting in improved ΔF/F ratios.

Our results show that the fluorescence recovery kinetics of ANNINE-6plus closely follow the voltage changes during membrane repolarization measured with intracellular microelectrodes in the absence and presence of the dye. In contrast, the late repolarization was slightly, yet significantly, delayed in optical action potentials measured with ANNINE-6 compared to the electrical signal. The reason for this is unclear, but may involve potential effects of the solvent and/or surfactant in the dye loading solution, and/or result from the different molecular structure of the water-insoluble probe. Surprisingly, we found that ANNINE-6plus itself in the absence of light excitation slightly increased phase 0 action potential amplitude and maximal upstroke velocity of in situ cardiomyocytes. Several mechanisms may underlie these changes, including increases in ionic currents that flow across the cardiomyocyte membrane and between adjacent cells during the rising phase of the action potential, a decrease in cytoplasmic and/or gap junctional resistance, reduction of cardiomyocyte membrane capacitance, and removal of inactivation of the fast, voltage-dependent sodium current (30). In this context, the observation that the peak fractional fluorescence change at the end-to-end junction was significantly larger than that at the t-tubule and side membranes in hearts loaded with either dye might reflect subcellular heterogeneity in the magnitude of the fast sodium current, which dominates action potential upstroke. Such spatial subcellular profiles have been described previously, using mathematical models of discontinuous impulse propagation (30–32). It remains to be determined, however, whether the subcellular nonuniformity of the peak fractional change in fluorescence merely reflects pharmacological effects of the dye itself on the action potential phase 0 depolarization, or whether it represents a physiological phenomenon.

Collectively, the high voltage sensitivity of ANNINE-6plus paired with its stable and selective binding to the sarcolemmal membrane of cardiomyocytes facilitate its use for mapping of transmembrane voltage changes on a subcellular scale. Our results further suggest that the water insoluble ANNINE-6 (in combination with the additives Pluronic F-127 and DMSO) prolongs action potential duration and thus is less suitable for optical imaging of transmembrane repolarization.

Uniformity in membrane repolarization throughout the sarcolemmal membrane of in situ cardiomyocytes

The results presented in this study show that action potential repolarization is uniform throughout the cardiomyocyte membrane. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to systematically investigate transmembrane voltage changes during the cardiomyocyte action potential on a subcellular scale. Hüser and coworkers (17) used laser-scanning confocal microscopy in line-scan mode (2 ms temporal resolution) in combination with the voltage-sensitive dye di-8-ANEPPS to independently monitor changes in transmembrane potential in voltage-clamped ventricular cardiomyocytes. Windisch et al. (16) developed a multisite imaging system to simultaneously monitor transmembrane voltage changes with spatial and temporal resolution of 15 μm and 20 μs, respectively, in single guinea pig ventricular myocytes loaded with di-4-ANEPPS, but their measurements did not distinguish between t-tubular and cell surface optical signals, and the analyses were restricted to the action potential upstroke. Knisley et al. (15) and Sharma et al. (18) used a similar approach to map the spatial dependence of polarization of the cell membrane during electrical field stimulation of isolated cardiomyocytes. None of these studies, however, provided systematic analyses of spatial subcellular profiles of transmembrane voltage changes throughout the cardiomyocyte action potential.

Previous studies had demonstrated uneven distribution of transmembrane currents on a subcellular scale in mammalian ventricular myocytes. Using formamide-induced detubulation (that seals off the t-tubules leaving them functionally intact but physically disconnected from the surface sarcolemma (33)), it was shown that the densities of the L-type calcium current (ICa.L), the Na/Ca exchange activity, and the Na+/K+-ATPase activity (5,6,34) are preferentially concentrated in the t-tubules of ventricular myocytes, whereas K+ currents were found to be approximately evenly distributed between the surface and t-tubule membranes (35). Using the whole-cell current-clamp technique, Brette and coworkers (5) were able to show that the transmembrane action potentials recorded from detubulated myocytes (i.e., surface membrane only) were markedly shorter than those recorded from control myocytes (i.e., t-tubules and surface membranes), but resting membrane and action potential phase 0 amplitude were similar. The difference in the repolarization time course was largely ascribed to the greater magnitude of net inward current mediated by ICa.L in the t-tubules. Modeling calculations based on these measurements suggested that the t-tubule action potential should be by a factor of ∼5.5 longer than at the cell surface (6,36), when the t-tubule and surface membranes are electrically isolated. In a normal myocyte, however, the action potential was predicted to be spatially uniform throughout the sarcolemmal membrane because of the tight electrical coupling between the surface and t-tubule membranes. Indeed, the results presented in this study directly confirm the latter prediction and are compatible with the notion that the action potential is the mean of that generated by the two sarcolemmal membranes. Also, the excellent agreement between the optical signals typically recorded from a few microns long membrane patches and the electrical signals, which measure electrical activity at the whole cell level, is consistent with tight electrical coupling throughout the sarcolemmal membrane of in situ cardiomyocytes. This behavior is also expected from the large space constant of the t-tubular system, which has been estimated previously to be 226 μm (36), with respect to the average length of t-tubular segments (∼7 μm; (37)), and the long sampling interval of our recording system (∼0.8 to ∼1.0 ms) with respect to the short membrane charging time constant that is on the order of microseconds (38,39).

Because of the limited bandwidth of our imaging system, we restricted the analyses to the repolarization phases of the action potential. However, within the temporal resolution of our technique, we found that the time course of changes in normalized fluorescence intensity during the action potential upstroke were spatially uniform within individual t-tubules. This observation is consistent with the idea that tight electrical coupling between the t-tubule and surface membranes ensures synchronous membrane potential changes across the entire cell membrane even during the fast and large voltage changes typically encountered during the rising phase of the transmembrane action potential. In support of this notion, a high level of temporal synchronization during the upstroke in the range of tens of microseconds (16) has been reported previously for isolated guinea-pig ventricular myocytes.

Although model calculations for rat ventricular myocytes have predicted action potential uniformity on a subcellular scale at frequencies ≤5 Hz (40), it is possible that spatial discrepancies develop at higher heart rates typically encountered in mice. In this context it is of interest that a recent study in isolated mammalian skeletal muscle fibers loaded with di-8-ANEPPS the time course of the t-tubular optical signal elicited by action potentials was almost indistinguishable from that of the electrically measured transmembrane potential during a single action potential (41). However, trains of action potentials at tetanic frequencies unmasked time-dependent discrepancies between the optical and electrical signals, indicating spatial nonuniformity of action potentials. Voltage-changes secondary to use-dependent phenomena such as ion accumulation (depletion) in the t-tubule lumen in combination with altered passive electrical parameters have been implicated in this process (41). Whether similar frequency-dependent microheterogeneities can develop in mammalian heart remains to be determined. Previous studies have shown that K+ and Ca2+ ions can accumulate or become depleted in distinct areas in the t-tubule lumen, which might give rise to membrane potential heterogeneities under certain circumstances (2–4,7).

The majority of studies examining spatial micro-heterogeneity of electrical properties have been conducted in single ventricular cardiomyocytes from rat. However, it seems unlikely that the observations presented here are species-specific for several reasons. First, both the magnitude and time course of whole-cell ICa.L similarly influence the shape and duration of the ventricular action potential in either species (42,43). Second, the fraction of t-tubular membrane to the total sarcolemmal membrane is almost identical for mouse and rat cardiomyocytes (5,6). Third, although direct evidence for subcellular nonuniformity of ICa.L density does not exist, most recent observations suggest that the mouse t-tubular membrane exhibits functional specialization that is similar to that seen in rats (44).

Our study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to describe an experimental approach that allows systematic and direct evaluation of the electrical activity at the t-tubular membrane or any other portion of the sarcolemma within individual cardiomyocytes. Its use should therefore enable future studies examining the modulation of transmembrane voltage profiles at the subcellular level in response to rate changes, and in response to functional and/or structural remodeling of the t-tubular system that has been previously shown to occur in the diseased myocardium (45,46).

Limitations of the study

Despite the excellent agreement of our observations with both experimental findings and theoretical predictions by others, the possibility that the experimental conditions used in this study might obscure subcellular heterogeneities in the time course of transmembrane repolarization, warrants further discussion. First, experiments were conducted in the presence of cytochalasin D, which at concentrations similar to those used in this study has been shown previously to reduce peak fast sodium current (INa) and also to slow its inactivation (47). The latter effect may give rise to action potential prolongation, which if occurring predominately at the surface membrane, might nullify action potential differences between the surface and t-tubule membranes. Although INa has been shown to be more concentrated at the surface membrane in ventricular myocytes (48), it seems extremely unlikely that a slower decay of INa at the surface membrane in the presence of cytochalasin D precisely offsets the magnitude of the difference in net transtubular current mediated by ICa,L and INCX.

Second, cytochalasin D does not interrupt the spatially and temporally synchronous Ca2+ release throughout in situ cardiomyocytes (49), indicating that a preferential decrease in ICa at the t-tubule membrane is unlikely to explain the uniformity of the action potential under our experimental conditions.

Third, because inactivation of ICa by SR Ca2+ release is more pronounced at the t-tubules than at the surface membrane of ventricular myocytes (50), inhibiting SR Ca2+ release by ryanodine would be expected to relax ICa inactivation more at the t-tubules, resulting in a disproportionally larger increase in Ca2+ entry via ICa at the t-tubules than at the surface membrane during a cardiac action potential. Because Ca2+ entry via ICa at the t-tubules has been shown to significantly exceed that at the cell surface under control conditions (5), ryanodine-induced attenuation of ICa inactivation is likely to accentuate preexisting differences in the magnitude of Ca2+ entry, and thus net cation influx, between the two membrane compartments, resulting in an increase, rather than decrease, in spatial nonuniformities of action potential duration.

Conclusion

We have developed and validated what we believe is a novel imaging approach that is capable of monitoring changes in transmembrane voltage on a subcellular scale within the intact mouse heart with ∼1 ms resolution. The technique can be readily implemented using standard laser scanning microscopes and laser illumination sources in combination with the water-soluble fast response dye ANNINE-6plus, and filtering algorithms to optimize voltage discrimination. Our data provide what to our knowledge are the first direct measurements of voltage changes across the t-tubular membranes of ventricular cardiomyocytes, or any cardiomyocyte type in general. Further, our data support the concept that despite previously documented differences in net cation entry between the t-tubule and surface membranes during the repolarization phases of the cardiac action potential, tight electrical coupling between these two membrane compartments confers uniformity in action potential duration throughout the sarcolemma in individual ventricular cardiomyocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. J. Field and Mark H. Soonpaa for suggestions and carefully reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (M.R.) and the American Heart Association (G.B.).

Appendix A: Optimal filtering algorithm

Transmembrane action potentials of mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes typically contain high- (phase 0) and low-frequency (phases 1–4) components (see Fig. 5 E). Traditional low-pass filtering approaches distort fast changes in membrane potential as those typically occurring during the action potential phase 0 depolarization. The design objective for this filter algorithm was to suppress noise while preserving the upstroke and also beat-to-beat signal variations. This algorithm is similar to an algorithm based on filtered residue method for cardiac biosignal filtering previously developed by Iravanian and Tung (51). Whereas Iravanian and Tung assumed that the signal is stationary and periodic, here we assumed that only the upstrokes are stationary and that they can be separated from other phases in the frequency domain.

The filter design assumes that the raw data has N action potentials contaminated by noise in a recording and each action potential is

| (A1) |

where si is the true signal and ni is the noise. Alignment of each action potential and subsequent signal averaging yields

| (A2) |

To calculate the appropriate filter, an estimate of the underlying noise, δi, is necessary. The estimate of the noise was found by subtracting the signal average, , from the raw data, xi:

| (A3) |

The high frequency noise, δi,H, was enhanced by removing the low frequency components, , using a 51-point moving average filter:

| (A4) |

Subsequently, δi,H is removed from the raw data to obtain the resulting, filtered action potentials:

| (A5) |

Assumptions were made in the above calculation and can be shown by expanding and rearranging Eq. A5.

| (A6) |

where sx,H and nx,H (x = i,j) are the high frequency component of signal and noise, respectively. sx,H is mainly from phase 0 and is assumed to be stationary. If N is large enough, stationarity allows us to assume that two of the terms in Eq. A6 are approximately zero:

| (A7) |

| (A8) |

Hence the high frequency noise component is effectively suppressed. The estimation of the signal is then written as

| (A9) |

The 51-point moving average filter has a low cut-off frequency of ∼9 Hz (sampling rate at 1042 Hz) and has minimal effect on the signal, whereas the noise is markedly suppressed. It is noted that this algorithm is sensitive to the type and the cut-off frequency of the low-pass filter that is used to reduce the noise. Chebyshev and Butterworth filters with various cut-off frequencies, and a moving average filter with various lengths were tested. We found that a 51-point moving average filter yielded the largest noise suppression. Examples of the application of the optical filter algorithm to the optical signals are shown in Figs. 2 and 7, and in Fig. S2.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Tidball J.G., Smith R., Shattock M.J., Bers D.M. Differences in action potential configuration in ventricular trabeculae correlate with differences in density of transverse tubule-sarcoplasmic reticulum couplings. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1988;20:539–546. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(88)80080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blatter L.A., Niggli E. Confocal near-membrane detection of calcium in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium. 1998;23:269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark R.B., Tremblay A., Melnyk P., Allen B.G., Giles W.R. T-tubule localization of the inward-rectifier K+ channel in mouse ventricular myocytes: a role in K+ accumulation. J. Physiol. 2001;537:979–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swift F., Strømme T.A., Amundsen B., Sejersted O.M., Sjaastad I. Slow diffusion of K+ in the T tubules of rat cardiomyocytes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006;101:1170–1176. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00297.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brette F., Sallé L., Orchard C.H. Quantification of calcium entry at the t-tubules and surface membrane in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2006;90:381–389. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brette F., Orchard C.H. Resurgence of cardiac t-tubule research. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:167–173. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00005.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen I.S., Kline R.P. K+ fluctuations in the extracellular spaces of cardiac muscles. Circ. Res. 1982;50:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fromherz P., Muller C.O. Cable properties of a straight neurite of a leech neuron probed by a voltage-sensitive dye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4604–4608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullen A., Patel S.S., Saggau P. High-speed, random-access fluorescence microscopy: 1. High-resolution optical recording with voltage-sensitive dyes and ion indicators. Biophys. J. 1997;73:477–491. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78086-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullen A., Saggau P. High-speed, random-access fluorescence microscopy: II. Fast quantitative measurements with voltage-sensitive dyes. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2272–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77383-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dombeck D.A., Sacconi L., Blanchard-Desce M., Webb W.W. Optical recording of fast neuronal membrane potential transients in acute mammalian brain slices by second-harmonic generation microscopy. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3628–3636. doi: 10.1152/jn.00416.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher J.A., Barchi J.R., Welle C.G., Kim G.H., Kosterin P. Two-photon excitation of potentiometric probes enables optical recording of action potentials from mammalian nerve terminals in situ. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;99:1545–1553. doi: 10.1152/jn.00929.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhn B., Denk W., Bruno R.M. In vivo two-photon voltage-sensitive dye imaging reveals top-down control of cortical layers 1 and 2 during wakefulness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7588–7593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802462105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glover J.C., Sato K., Sato Y. Using voltage-sensitive dye recording to image the functional development of neuronal circuits in vertebrate embryos. Dev. Neurobiol. 2008;68:804–816. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knisley S.B., Blitchington T.F., Hill B.C., Grant A.O., Smith W.M. Optical measurements of transmembrane potential changes during electric field stimulation of ventricular cells. Circ. Res. 1993;72:255–270. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Windisch H., Ahammer H., Schaffer P., Müller W., Platzer D. Optical multisite monitoring of cell excitation phenomena in isolated cardiomyocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:508–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00373887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hüser J., Lipp P., Niggli E. Confocal microscopic detection of potential-sensitive dyes used to reveal loss of voltage control during patch-clamp experiments. Pflugers Arch. 1996;433:194–199. doi: 10.1007/s004240050267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma V., Tung L. Spatial heterogeneity of transmembrane potential responses of single guinea-pig cardiac cells during electric field stimulation. J. Physiol. 2002;542:477–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn B., Fromherz P., Denk W. High sensitivity of Stark-shift voltage-sensing dyes by one- or two-photon excitation near the red spectral edge. Biophys. J. 2004;87:631–639. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fromherz P., Hübener G., Kuhn B., Hinner M.J. ANNINE-6plus, a voltage-sensitive dye with good solubility, strong membrane binding and high sensitivity. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008;37:509–514. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bu G., Berbari E.J., Rubart M. Optical recording of action potentials from isolated perfused mouse hearts with cellular resolution. Biophys. J. 2007 Supplement, 20a, Abstract, 718-Pos. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bu G., Berbari E.J., Rubart M. Optical recording of single cardiomyocyte transmembrane potential in Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Comput. Cardiol. 2007;34:357–360. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Opie L.H. Mechanisms of cardiac contraction and relaxation. In: Libby P., Bonow R.O., Mann D.L., Zipes D.P., Braunwald E., editors. Heart Disease. Saunders/Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2008. pp. 509–539. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dilly K.W., Rossow C.F., Votaw V.S., Meabon J.S., Cabarrus J.L. Mechanisms underlying variations in excitation-contraction coupling across the mouse left ventricular free wall. J. Physiol. 2006;572:227–241. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knollmann B.C., Schober T., Sirenko S.G., Franz M.R. Action potential characterization in intact mouse heart: steady-state cycle length dependence and electrical restitution. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;292:H614–H621. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01085.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaffer P., Ahammer H., Müller W., Koidl B., Windisch H. Di-4-ANEPPS causes photodynamic damage to isolated cardiomyocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1994;426:548–551. doi: 10.1007/BF00378533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin H., Kay M.W., Chattipakorn N., Redden D.T., Ideker R.E. Effects of heart isolation, voltage-sensitive dye, and electromechanical uncoupling agents on ventricular fibrillation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;284:H1818–H1826. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00923.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardy M.E.L., Lawrence C.L., Standen N.B., Rodrigo G.C. Can optical recordings of membrane potential be used to screen for drug-induced action potential prolongation in single cardiac myocytes? J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2006;54:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohr S., Salzberg B.M. Multiple site optical recording of transmembrane voltage (MSORTV) in patterned growth heart cell cultures: assessing electrical behavior, with microsecond resolution, on a cellular and subcellular scale. Biophys. J. 1994;67:1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80602-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kléber A.G., Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:431–488. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spach M.S., Heidlage J.F. The stochastic nature of cardiac propagation at a microscopic level: electrical description of myocardial architecture and its application to conduction. Circ. Res. 1995;76:366–380. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw R.M., Rudy Y. Ionic mechanisms of propagation in cardiac tissue. Roles of the sodium and L-type calcium currents during reduced excitability and decreased gap junction coupling. Circ. Res. 1997;81:727–741. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brette F., Komukai K., Orchard C.H. Validation of formamide as a detubulation agent in isolated rat cardiac cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H1720–H1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00347.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Despa S., Brette F., Orchard C.H., Bers D.M. Na/Ca exchange and Na/KATPase function are equally concentrated in transverse tubules of rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3388–3396. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74758-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komukai K., Brette F., Yamanushi T.T., Orchard C.H. K(+) current distribution in rat sub-epicardial ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:532–538. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pásek M., Simurda J., Christé G., Orchard C.H. Modeling the cardiac transverse-axial tubular system. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2008;96:226–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soeller C., Cannell M.B. Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ. Res. 1999;84:266–275. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehrenberg B., Farkas D.L., Fluhler E.N., Lojewska Z., Loew L.M. Membrane potential induced by external electric field pulses can be followed with a potentiometric dye. Biophys. J. 1987;51:833–837. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83410-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tung L., Sliz N., Mulligan M.R. Influence of electrical axis of stimulation on excitation of cardiac muscle cells. Circ. Res. 1991;69:722–730. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pásek M., Simurda J., Christé C.G. The functional role of cardiac T-tubules explored in a model of rat ventricular myocytes. Philos. Transact. A. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2006;364:1187–1206. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2006.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DiFranco M., Capote J., Vergara J.L. Optical imaging and functional characterization of the transverse tubular system of mammalian muscle fibers using the potentiometric indicator di-8-ANEPPS. J. Membr. Biol. 2005;208:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0825-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bondarenko V.E., Szigeti G.P., Bett G.C.L., Kim S., Rasmusson R.L. Computer model of action potential of mouse ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H1378–H1403. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00185.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandit S.V., Clark R.B., Giles W.R., Demir S.S. A mathematical model of action potential heterogeneity in adult rat left ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2001;81:3029–3051. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75943-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]