Abstract

Background

Although bivalves are among the most-studied marine organisms because of their ecological role and economic importance, very little information is available on the genome sequences of oyster species. This report documents three large-scale cDNA sequencing projects for the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas initiated to provide a large number of expressed sequence tags that were subsequently compiled in a publicly accessible database. This resource allowed for the identification of a large number of transcripts and provides valuable information for ongoing investigations of tissue-specific and stimulus-dependant gene expression patterns. These data are crucial for constructing comprehensive DNA microarrays, identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms and microsatellites in coding regions, and for identifying genes when the entire genome sequence of C. gigas becomes available.

Description

In the present paper, we report the production of 40,845 high-quality ESTs that identify 29,745 unique transcribed sequences consisting of 7,940 contigs and 21,805 singletons. All of these new sequences, together with existing public sequence data, have been compiled into a publicly-available Website http://public-contigbrowser.sigenae.org:9090/Crassostrea_gigas/index.html. Approximately 43% of the unique ESTs had significant matches against the SwissProt database and 27% were annotated using Gene Ontology terms. In addition, we identified a total of 208 in silico microsatellites from the ESTs, with 173 having sufficient flanking sequence for primer design. We also identified a total of 7,530 putative in silico, single-nucleotide polymorphisms using existing and newly-generated EST resources for the Pacific oyster.

Conclusion

A publicly-available database has been populated with 29,745 unique sequences for the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. The database provides many tools to search cleaned and assembled ESTs. The user may input and submit several filters, such as protein or nucleotide hits, to select and download relevant elements. This database constitutes one of the most developed genomic resources accessible among Lophotrochozoans, an orphan clade of bilateral animals. These data will accelerate the development of both genomics and genetics in a commercially-important species with the highest annual, commercial production of any aquatic organism.

Background

Genome research on the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, has been facilitated by the recent development of species-specific tools such as linkage maps [1,2], large-insert libraries [3], a public clearing-house [4], and gene expression profiles [5-7]. Several factors motivate further development of genomic resources for C. gigas: (I) Because this species has the highest annual production of any aquatic organism, C. gigas has been the subject of a great deal of research to elucidate the molecular basis underlying the physiological and genetic mechanisms of economically-relevant traits. (II) The Pacific oyster's phylogenic position in the Lophotrochozoa, an understudied clade of bilaterian animals, makes molecular data on C. gigas highly relevant for studies of genome evolution. (III) Oysters play an important role as sentinels in estuarine and coastal marine habitats where increasing human activities exacerbate the impacts of disease and stress in exploited populations. (IV) C. gigas can be an invasive species when introduced into new habitats [8]. As a result, the Pacific oyster is becoming an attractive model species for genome-related research activities focusing on comparative immunology [e.g. [9-11]], disease ecology [e.g. [12-14]], stress response to pollutants and parasites [e.g. [15]], developmental and reproductive physiology [e.g. [16,17]] and evolutionary genetics [e.g. [18-20]].

The genomic strategies currently employed for the identification of novel and previously-characterized genes affecting phenotypes of interest in the Pacific oyster include the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL), and high-throughput studies of gene expression [21]. QTL mapping of genetic variation affecting, for example, resistance to summer mortality [22] or hybrid vigor [6] requires a large number of mapped molecular markers and testing for associations between marker genotypes and phenotypes to identify chromosomal regions harbouring genes that directly affect the trait of interest. Recently developed BAC libraries and fingerprinting [3] (P. Gaffney, Pers. Com.), have facilitated fine mapping of such regions, and ultimately specification of marker position on the genetic linkage map, allowing gene-assisted selection. Functional genomic approaches are also required for gene-expression profiling experiments such as macroarrays [17], microarrays [7], SAGE (Serial Analysis of Gene Expression), MPSS (Massively Parallel Signature Sequencing) [6], or technologies addressing single genes, such RT-qPCR (real-time quantitative PCR). These techniques have potential applications in ecological monitoring [23], evaluating oyster broodstock for selective breeding and understanding of gene regulation involved, for example, in the molecular pathways associated with responses to stress or pathogens.

In the present paper, we report the generation and analysis of 47,889 ESTs by sequencing clones from the Network of Excellence "Marine Genomics Europe" (MGE) normalized gonad cDNA library (partially published in [24]), and two other projects: I) the Genoscope project (CEA Evry, France) and II) the European Aquafirst project (Table 1). The objective of the Genoscope project (EST sequencing from Crassostrea gigas) was to substantially expand genomic information on oysters by sequencing ESTs from: (I) a normalized "hemocyte" cDNA library constructed with mRNA from bacteria-challenged and unchallenged hemocytes, and (II) ESTs from an "all developmental stages and Central Nervous System (CNS)" normalized cDNA library derived from mRNA extracted from all embryonic and larval stages, as well as from adult visceral ganglia. The European "Aquafirst" project that uses genetic and functional genomic approaches to develop summer mortality resistance markers in oysters, produced ESTs by suppression subtractive hybridization between Resistant and Sensitive oyster lines in six different tissues [25]. To maximize the utility of these collections, ESTs from all of these efforts, together with those in public databases (e.g. [26]), have been assembled in a unique public database: the GigasDatabase http://public-contigbrowser.sigenae.org:9090/Crassostrea_gigas/index.html containing 29,745 unique sequences.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of the Pacific oyster cDNA libraries.

| Description | Tissue | Vector used | No. of sequences retrieved | No. of valid sequences | Average length insert (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA gonad * | gonad | PAL32CV | 12162 | 8809 | 511 |

| cDNA embryos and larvae and central nervous system (GENOSCOPE) | embryos, larvae, CNS | pAL17.3 | 13191 | 12730 | 618 |

| cDNA hemocytes (GENOSCOPE) | hemocyte | pBluscriptIISK+ | 14472 | 13773 | 415 |

| cDNA digestive gland subtracted library (AQUAFIRST) | digestive gland | PCR2.1 | 1536 | 1362 | 428 |

| cDNA mantle-edge subtracted library (AQUAFIRST) | mantle-edge | PCR2.1 | 1536 | 1343 | 405 |

| cDNA hemocyte subtracted library (AQUAFIRST) | hemocyte | PCR2.1 | 1152 | 125 | 291 |

| cDNA gonad subtracted library (AQUAFIRST) | gonad | PCR2.1 | 768 | 559 | 382 |

| cDNA muscle subtracted library (AQUAFIRST) | muscle | PCR2.1 | 1536 | 1117 | 312 |

| cDNA gills subtracted library (AQUAFIRST) | gills | PCR2.1 | 1536 | 1027 | 359 |

| Total | 47889 | 40845 | Mean: 413 |

* Library partially published in Tanguy et al.[25] with 1894 sequenced clones.

This resource is highly valuable for identifying important gene networks controlling physiological processes, it facilitates the development of molecular markers for the construction of a reference genetic map, and it allows large-scale, expression-profiling experiments using microarrays. These tools will be useful to advance our knowledge of the genetic and physiological bases of development, reproduction, immunology, and associated processes that are important for oyster aquaculture. Finally, this work will be very useful for the annotation phase of the entire oyster genome, the principal objective of an international community of oyster biologists [27] that will provide a critical point of comparison for understanding the early diversification of animals and their genome, as has been recently proposed for the gastropod snail Lottia gigantea http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Lotgi1/Lotgi1.home.html.

Construction and content

1. Biological samples

1.1. Resistant and Sensitive oysters for the subtractive libraries

Resistant (R) and Susceptible (S) oyster families were produced, through divergent selection for high or low survival of summer mortality, as fully described previously [25]. After completing rearing of oysters through larval development in the IFREMER hatchery in La Tremblade (France, July 2004), we transferred juvenile oysters to the nursery of Bouin (Vendée, France) until March 2005, when the oysters were deployed in the field at Fort Espagnol (South Brittany, France). We collected samples of gonad, muscle, digestive gland, hemocytes, mantle-edge, and gills from 12 R and 12 S oysters on two dates (May 25 and June 6, 2005) and individual tissues from each line were pooled at each sampling date.

1.2. Biological material for the "all developmental stages and central nervous system" cDNA library

Mature, wild oysters, collected on the Atlantic coast of Brittany (France), were spawned and reared in captivity as described in [28]. From this pool, we sampled various developmental stages, which we identified microscopically: oocytes before fertilization, 4-cell and 8-cell embryos (1 and 2 hours post-fertilization [hpf], respectively), morula (3 hpf), blastula (5 hpf), gastrula (7 hpf), trochophore larvae (16 hpf) and D-larvae (2 days post-fertilization [dpf]), early veliger larvae (7 dpf), later veliger larvae (14 dpf), pediveliger larvae (18 dpf), and spat after metamorphosis (27 dpf). We extracted total mRNA from one million oysters from each developmental stage from oocyte to trochophore, and 250,000 from later stages, and from the visceral ganglia microscopically dissected from 10 wild, adult oysters

1.3. Biological material for "hemocytes" cDNA library

We sampled hemocytes from six adult oysters exposed to each of 24 experimental conditions (total n = 144), all combinations of four kinds of bacterial challenge, two times post-challenge, and oysters collected from three geographic origins: Atlantic coast (La Tremblade), Normandie (Bay des Veys) and Mediterranean Sea (Thau lagoon). We performed the bacterial challenges by immersing oysters in seawater containing (I) live, non-virulent Micrococcus luteus and Vibrio tasmaniensis (2.5 × 108 bacteria/L for each strain), (II) live, virulent Vibrio splendidus (5 × 108 bacteria/L), (III) a mix of heat-killed, virulent Vibrio splendidus and Vibrio aesturianaus (2.5 × 108 bacteria/L for each strain) and (IV) unchallenged oysters. For each condition, we collected hemolymph at 22 and 24 h post challenge from the pericardial cavity through the adductor muscle. We isolated hemocytes separately from these samples (24 experimental conditions) by centrifugation at 700 g for 10 min (4 C) and discarded the plasma. Hemocytes were further subjected to several experimental procedures (see below).

2. RNA preparation

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL) at a concentration of 1 ml/30 mg of tissue. For SSH experiments and hemocyte samples, we isolated polyadenylated RNA using the Quickprep micro mRNA purification kit (Amersham). We measured RNA concentration with a spectrophotometer at 260 nm using the conversion factor 1 OD = 40 μg/ml RNA, and RNA quality was determined using a Bioanalyser 2100 (Agilent).

3. cDNA library construction and sequencing of the clones

3.1. Construction of subtractive libraries

The mRNA from each pool of tissue RNA (6 tissues in total) was used as the template for SSH following the PCR-select cDNA subtraction kit procedure (Clontech). Hybridization and subtraction steps were carried out in both directions, i.e. for forward subtraction the Resistant (R) sample (tester) was subtracted from the Susceptible (S) sample (driver) and vice versa for reverse subtraction. The PCR products from both subtractions were cloned into pCR 2.1® TOPO plasmid using TOP10 One Shot ® competent cells for transformation (Invitrogen).

3.2. Construction of "all Developmental stages and central nervous system" cDNA library

Total RNA (0.3 μg) from a pool of various developmental stages and visceral ganglia was used for ds cDNA synthesis and amplification using the SMART approach. Recovered cDNA was equalized using the Duplex-Specific nuclease (DSN)-based normalization method [29]. Efficiency of normalization was measured by real-time PCR. A severe decrease (shift of 11 amplification cycles) in actin relative copy number was measured in the normalized cDNA sample, when compared to the non normalized sample. Resulting, normalized cDNA was then amplified, directionally cloned into pAL17.3 plasmid (Evrogen, Moscow), and was used to transform the XL1-Blue E. coli strain (Stratagene) to generate a cDNA library of 5 × 105 independent clones.

3.3 Construction of oyster "hemocytes" cDNA library

The cDNA library was built by GATC Biotech AG (Germany). Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA, composed of equimolar concentrations from oyster hemocytes from each of the 24 experimental conditions, was used for ds cDNA synthesis. The normalization method consisted of denaturation and controlled, incomplete reassociation of double-stranded cDNA, followed by selective cloning of the cDNA corresponding to the single-stranded, normalized fraction. Efficiency of normalization was measured by non-radioactive, Reverse Northern blot analysis of normalized and non-normalized cDNA. Briefly, an array containing 96 randomly-selected clones derived from the non-normalized cDNA library was hybridized with normalized and non-normalized cDNA. Comparison of homogenization of hybridization signals from the normalized probe to the non-normalized probe indicated the efficiency of normalization (data not shown). Normalized cDNA was then amplified, directionally cloned into pBluescriptIISK(+) plasmid (Stratagene), and was used to transform E. coli XL1-BlueMRF' (Stratagene) to generate a normalized cDNA library of 8.3 × 104 independent clones.

3.4. Sequencing

For subtracted libraries and the normalized cDNA gonad library [24], the clones were sequenced at the Max Planck Institute platform (Berlin, Germany) using an ABI 3730 automatic capillary sequencer, the ABI Big Dye Terminator sequencing kit and universal primer. For the two other normalized cDNA libraries, sequencing was performed at the Genoscope facility (CEA Evry, France) as described above.

4. Database, sequence processing and contig assembly

The data files produced were processed by SIGENAE; documentation of procedures is available on the SIGENAE website http://www.sigenae.org/index.php?id=9. The resource data flow has been compiled in the GigasDatabase http://public-contigbrowser.sigenae.org:9090/Crassostrea_gigas/download, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Processing chain of the GigasDatabase. The data resources of the GigasDatabase includes cleaning processes, batch statistics, assembling sequences into contigs, annotation of the contigs, visualization of the contigs, and summary statistics concerning each library.

The sequences were first cleaned up from vector and adaptator sequences. Repeats and contaminants were removed by comparison with several sequence databases such as Univec, Yeast and E. coli genomes. The PolyA site was identified by its relative position to the vector multiple-cloning site. In the 30 bases preceding the polyA site, we searched for putative polyadenylation signals (AATAAA and ATTAAA) [30]. Valid sequences, that had a PHRED score over 20 on at least 100 bp, were submitted to the EMBL-EBI Nucleotide Sequence database http://www.ebi.ac.uk/embl/. Because of the large number of sequences, we used a two-step process to assemble these sequences into contigs. The first step built clusters of sequences sharing at least 75 bp with an identity rate of 96% using MegaBlast [31]. The second step constructed coherent contigs from the previous clusters using CAP3 [32], at the recommended stringency of 40 bp overlap with 90% sequence identity. Once the contigs were built and their annotation completed, all data were loaded in a locally-adapted Ensembl database.

To obtain as much information as possible concerning the contigs, we performed similarity searches with BlastX http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi using a variety of databases: UniProt/SwissProt, UniProt/TrEMBL, ProDom (protein domains), UniGene Human Clusters, UniGene taxon specific Clusters, TIGR Taxon Specific Clusters, Ensembl specific transcripts (cDNA), and other Sigenae Contigs. We then loaded the annotations into the GigasDatabase. We identified putative open-reading frames (ORFs) by choosing the longest possible translation into amino acid sequence, using Emboss sixpack http://bioweb2.pasteur.fr/docs/EMBOSS/sixpack.html. Sequences with ORFs smaller than 100 codons (300 bp) were removed from the dataset.

5. Gene ontology annotation

To link ESTs with BlastX hits with putative function, we annotated all of them according to gene ontology (GO) terms by using the program KAAS (KEGG Automatic Annotation Server: http://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/), which provides functional annotation of genes by Blast comparisons (single best hit) against the manually curated KEGG Genes database [33]. The top level consists of the following categories: metabolism, genetic information processing, environmental information processing, and cellular processes. The second level divides these functional categories into finer sub-categories [34]. The distribution of genes in each of the main ontology categories was examined, and the percentages of unique sequence in each of the assigned GO terms were computed.

6. in silico mining of microsatellites and SNPs

We searched a set of 56,327 unique sequences for microsatellite markers using SRR finder (http://www.maizemap.org/bioinformatics/SSRFINDER/SSR_Finder_Download.html; [35]) with a minimum repeat of 4. This provided a table of raw data which was then exported to MS Excel® to calculate the number of di-, tri-, and tetra-nucleotide repeats, their respective lengths, and starting positions. Putative SNPs were detected using the Pupasuite v1.0 (http://pupasuite.bioinfo.cipf.es/, [36]). The 56,327 ESTs were assembled in 7,940 contigs wherein putative SNPs were identified and characterized to calculate the percentage of each type of mutation (ts/tv, synonymous/non-synonymous).

Utility and discussion

1. Generation of ESTs

To augment the 1894 recently-published sequences from the normalized cDNA libraries produced by the "Marine Genomic Europe" program [24], we sequenced a novel part of the gonad library. In addition, we also constructed two new, directionally-cloned, normalized oyster cDNA libraries: one including all developmental stages from embryos to larvae and visceral ganglia, and one from bacteria-challenged and unchallenged hemocytes. Single-pass sequencing produced sequences from the 5' regions of mRNA from each library, resulting in 12,162 sequences, 13,191 sequences, and 14,472 sequences, respectively (Table 1).

Finally, to increase the number of genes characterized that are related to summer mortality [13,14,17], we constructed libraries from six different tissues (digestive gland, mantle-edge, hemocytes, gonad, muscle, and gills) using Suppression Subtractive Hybridization (SSH) between selectively-bred Resistant (R) and Sensitive (S) oyster lines [25], by subtracting in both directions (R-S and S-R). These SSH libraries produced of a total of 8,064 sequences, with approximately 1,000 sequences per library (Table 1). All 47,889 sequences were subjected to pre-processing to eliminate poor-quality sequences and remove cloning-vector sequences. After removing clones with very short inserts or no inserts, and those with poor sequence quality, we obtained a total of 40,845 (85.3%) high-quality ESTs with an average length of 413 bp (Table 1). All EST sequences have been deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers [AM857416-AM869575] for gonad library, [CU998430–CU999999; FP000001–FP012228] for hemocyte library, [CU983906–CU998429] for developmental stages and visceral ganglia library, and [CU681473–CU681818; CU682012–CU682338; CU683068–CU683823; CU683828–CU683864; CU684729–CU686587; FP89705–FP89949] for the SSH libraries.

2. Contig assembly of the ESTs

The GigasDatabase http://public-contigbrowser.sigenae.org:9090/Crassostrea_gigas/index.html has been used for sequence processing, contig assembly, annotation, and project data hosting. All sequences, including public EST and mRNA sequences, as well as other data and results, can be accessed through the database. After assembly of the 40,845 new, valid ESTs and the 9,548 published sequences from GenBank into contigs, the database consists of 7,940 contigs and 21,805 singletons (Table 2). Thus, the GigasDatabase now contains 29,745 unique sequences from C. gigas with an average length of 798 bp (Table 2). As the NCBI actually contains 1325 sequences of C. gigas in the "nucleotide section", the release of these newly-generated ESTs will consequently improve the knowledge of sequences for this species.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of the ESTs generated from the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas available in the GigasDatabase.

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of high quality ESTs (new ESTs + public) | 56327 (40845 + 15482) |

| Average length of high quality ESTs (bp) | 798 |

| Number of contigs | 7940 |

| Number of ESTs in contigs | 34522 |

| Number of singletons | 21805 |

| Number of unique sequences | 29745 |

Of the 7,940 contigs, 4,208 contained 2 ESTs (53%), 1,588 contained 3 ESTs (20%), 794 contained 4 ESTs (10%), 397 contained 5 ESTs (5%), and relatively few sequences contained more than 6 ESTs (11%) (Table 3). These results indicate that most of the clusters were small, reflecting a high efficiency in normalization of the cDNA libraries.

Table 3.

BlastX searches and contig analysis for the complete collection of oyster contigs, based on GigasDatabase EST clustering.

| Number of unique sequences | 29745 |

| Number of unique sequences with BlastX hits | 12790 |

| Percentage of unique sequences with BlastX hits | 43% |

| Number of contigs containing: | |

| 2 ESTs | 4208 |

| 3 ESTs | 1588 |

| 4 ESTs | 794 |

| 5 ESTs | 397 |

| > 6 ESTs | 873 |

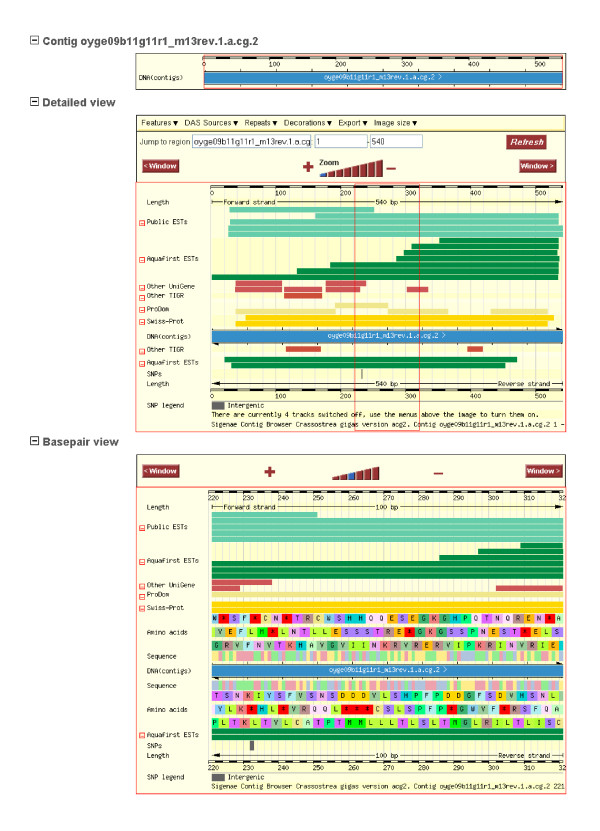

A graphical user interface permits the visualization of the data with different views, such as "ContigView" which gives a graphical overview of the contig structure and similarity annotations. Each sequence or similarity feature is represented as a line. The color of the line gives an indication of the type of sequence and all lines are described on the left of each panel (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphical view of the contig by "ContigView" available in GigasDatabase. The ContigView screen gives a graphical overview of the contig structure. Each sequence is represented as a line, and colors indicate the type of sequence. The first level corresponds to the sequence fragment overview. The second level is the detailed view of the individual sequences belonging to the contig. The red frame represents the visualized section on the third level. The third level is the base-pair view of the DNA contigs.

3. Putative identities of ESTs

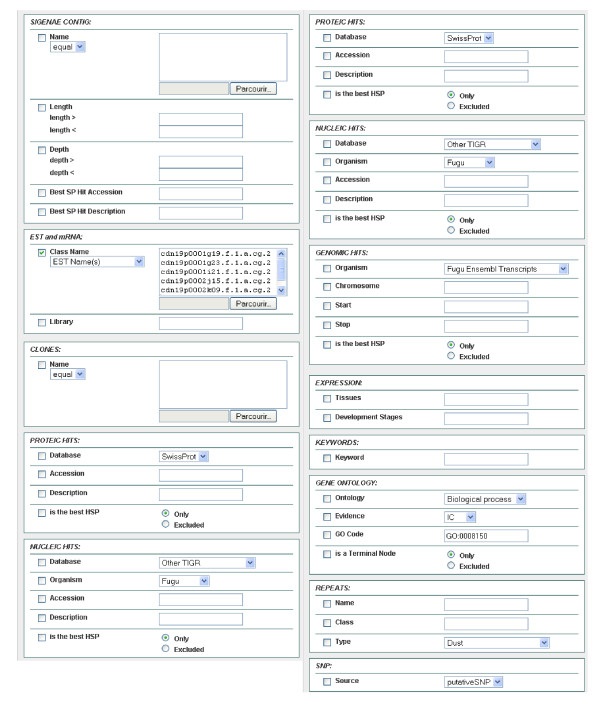

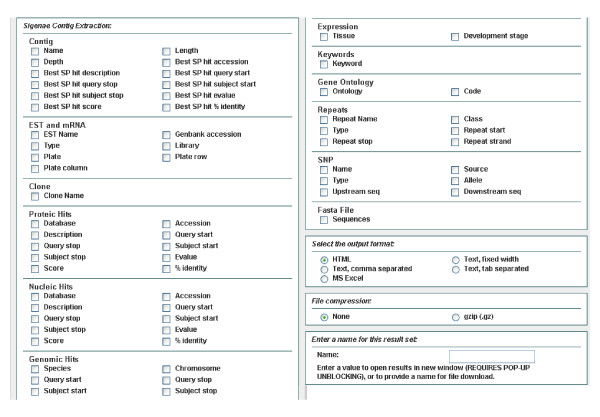

To determine the putative identities of the assembled contig and singleton sequences, we performed BlastX similarity searches on several protein databases. Of the 29,745 unique sequences, 12,790 (43%) had significant matches (E-value < 10-6) in the non-redundant protein database. This might be considered as low and due to ESTs within 3' untranslated regions (UTR) that can not be matched to protein sequences, and to the relatively short sequences (about 360 bp) obtained from the SSH libraries. Efforts should be made to generate complete cDNA sequences in C. gigas to provide a greater level of assessment of this organism's gene contents and similarities to various other species in the evolutionary spectrum. The complete list of these annotated sequences is reported in Additional File 1. All annotation data have been organized in the user-friendly GigasDatabase using "BioMart", which provides several tools to search cleaned and assembled ESTs. The user may input and submit several filters, such as contig names, EST names, protein hits, nucleotide hits, tissues of expression, as well as keywords, to the server using the web interface, as presented in Figure 3. Once the filters have been selected, it is also possible to select elements for the output files by checking the corresponding boxes in the output data blocks, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Filter page available with BioMart in GigasDatabase. Filter criteria are deposited in blocks. The name is in the upper left corner of the block, and this section contains a list of elements that can be used for selection, corresponding to one table in the database structure. The filter criteria can be based upon contigs, EST and mRNA, clones, protein hits, nucleotide hits, genomic hits, expression, keywords, gene ontology, repeats, and SNP.

Figure 4.

Output page available with BioMart in GigasDatabase. Once the filters have been selected, it is possible to select elements for output. For example, best SwissProt (SP) description, best SP hit score, or best SP hit E-value can be exported in several output formats (HTML, Text, MS Excel).

4. Gene ontology annotation

More-detailed, functional annotation was performed with BlastX using KAAS (KEGG Automatic Annotation Server: http://www.genome.jp/tools/kaas/). GO categories were successfully assigned to 7,733 (26%) unique ESTs. This low percentage of GO assignment has also been reported previously in C. gigas [24] and is probably linked to a high level of amino-acid sequence divergence between marine bivalves and the reference taxa currently used in genomics (such as Drosophila (FlyBase) and Caenorhabditis (WormBase)), and also to the relatively small average length of the ORFs. Table 4 shows the percentage distribution of gene ontology terms among the 7,733 annotated ESTs. The largest number of annotated sequences was found for a final GO term "Metabolism," which represents 42% of the annotated ESTs among all GO categories. Within this category, the higher GO terms were Amino Acid, Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolism, with 8, 7.6 and 6.3% of the annotated ESTs, respectively. For "Genetic Information Processing", 4.3 and 4.8% of the annotated ESTs were associated with translation and folding, and sorting degradation respectively. Many ESTs (10.7%) were linked to signal transduction, in the "Environmental Information Processing" category. Finally, Cell Communication (7.0%), Endocrine System (7.9%), and Immune System (4.9%) were the most abundant "Cellular Processes" subterms.

Table 4.

Gene ontology annotation using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server for the unique Crassostrea gigas sequences from the GigasDatabase.

| Categories | Number ESTs | % |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | 3244 | 41.9 |

| Carbohydrate Metabolism | 590 | 7.6 |

| Energy Metabolism | 302 | 3.9 |

| Lipid Metabolism | 484 | 6.3 |

| Nucleotide Metabolism | 153 | 2.0 |

| Amino Acid Metabolism | 619 | 8.0 |

| Metabolism of Other Amino Acids | 171 | 2.2 |

| Glycan Biosynthesis and Metabolism | 273 | 3.5 |

| Biosynthesis of Polyketides and Nonribosomal Peptides | 4 | 0.1 |

| Metabolism of Cofactors and Vitamins | 173 | 2.2 |

| Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites | 117 | 1.5 |

| Xenobiotics Biodegradation and Metabolism | 355 | 4.6 |

| Genetic Information Processing | 954 | 12.3 |

| Transcription | 76 | 1.0 |

| Translation | 335 | 4.3 |

| Folding, Sorting and Degradation | 370 | 4.8 |

| Replication and Repair | 173 | 2.2 |

| Environmental Information Processing | 1096 | 14.2 |

| Membrane Transport | 82 | 1.1 |

| Signal Transduction | 830 | 10.7 |

| Signaling Molecules and Interaction | 184 | 2.4 |

| Cellular Processes | 2439 | 31.5 |

| Cell Motility | 188 | 2.4 |

| Cell Growth and Death | 324 | 4.2 |

| Cell Communication | 544 | 7.0 |

| Endocrine System | 611 | 7.9 |

| Immune System | 381 | 4.9 |

| Nervous System | 160 | 2.1 |

| Sensory System | 90 | 1.2 |

| Development | 137 | 1.8 |

| Behavior | 3 | 0.0 |

| Total | 7733 | 100 |

"Number ESTs" indicates the number of ESTs associated in the corresponding Gene Ontology, and "%" the corresponding percentage. 100% was established as the total number of unique sequences (7733) having an assigned gene ontology term.

Among these different subcategories of GO, several ESTs potentially connected to physiological functions of the oyster linked with our subset of interest have been discovered (Table 5). For example, for TGFβ signaling regulating a variety of important processes, two new ligands, activin/myostatin and inhibin-like (Table 5), were identified that complete the already-large panel of ligands in C. gigas [11,37,38]. Indeed, the identification of new, potential members of the TGFβ superfamily contributes to the TGFβ signaling pathway being recognized as one of the best- characterized systems at the molecular level within lophotrochozoans.

Table 5.

Selection of some candidate Crassostrea gigas ESTs similar to genes potentially involved in some physiological regulatory networks.

| Accession No | Best hit description | |

|---|---|---|

| Endo- paracrine controls | CU997995 | activin/myostatin like |

| CU984230 | inhibin bA like | |

| CU998397, CU990571 | smad | |

| CU994284, CU991852, CU987529, CU984099, CU991056 | follistatin 1 | |

| CU998185, CU991852, CU983909, CU993729, CU987283, CU993729, CU988008 | thrombospondin | |

| FP011148 | cysteine rich bmp regulator 2 | |

| CU997999 | tolloid-like protein | |

| Energy metabolis m/reproduct ion | FP001644, FP008029, FP008849, FP002487, CU984370, CU989738, CU997056 | c1q-like adipose specific protein |

| FP000698 | leptin receptor overlapping transcript-like 1 | |

| FP010154, FP001573, CU993420, CU991531 | ovary-specific c1q-like factor | |

| FP008650 | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase p110 beta | |

| CU994294, CU990696 | acetyl-coenzyme a carboxylase alpha | |

| CU994253 | adiponectin receptor 1 | |

| CU993735 | camp-dependent protein kinase | |

| CU993270 | carnitine o-acyltransferase | |

| CU983945, FP005412, CU994912 | neuropeptide y | |

| CU991233, CU682842 | sterol regulatory element binding factor 1 | |

| Immunity | FP006535, FP010171, CU984422, FP005108, CU998652 | caspase |

| CU683654 | cactus | |

| CU999108, CU988309, CU993827 | myeloid differentiation primary response gene | |

| FP004666, FP011576, FP002604, CU995719 | toll | |

| CU989449, FP009504, CU998458, CU988135 | kappa-b | |

| CU684230 | big defensin | |

| FP010905 | gigasin 2 protein | |

| FP000856, FP003629, FP006010, FP006279, CU994639 | lbp bpi | |

| FP005503, CU999465, FP006037, FP011761 | lipopolysaccharide binding protein | |

| CU983947, CU996720, FP002226 | lps-induced tn factor | |

Concerning the allocation of energy to reproduction, which may play a crucial role in the ability of oysters to survive summer mortality [13,17], relevant genes potentially involved in the signaling pathway linking reproduction to energy balance have been retrieved, such as ESTs encoding PI3-kinase catalytic subunit beta enzyme (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta, Table 5), leptin receptor, adiponectin-like (ovary-specific c1q-like factor, c1q-like adipose specific protein, Table 5) and a neuropeptide Y ligand (Table 5). Such signaling molecules were recently identified in vertebrates and have important regulatory effects on reproduction [39,40]. For example, leptin and adiponectin were reported to promote fecundity and the growth of germinal cells by increasing the utilization of oxidizable sources. At the opposite, neuropeptide Y inhibits reproduction when energy storage is deficient [41,42].

Finally, concerning the innate immunity of C. gigas, new immune-system components have been identified, including signal-transduction elements, LPS binding proteins, antimicrobial peptides, and various protease inhibitors. In particular, a new component of the NF-κB pathway [43], a Toll receptor-like protein, has been sequenced. The most significant feature of the NF-κB pathway is the central role of the NF-κB family in transcriptional activator proteins, ubiquitously expressed and involved in wide variety of biological processes, including inflammation, cell proliferation and differentiation in mammals, as well as development in insects [44].

Further functional studies will be necessary, however, to demonstrate the involvement of these annotated ESTs in the different physiological processes of C. gigas. Indeed, this work encourages the use of functional studies, such as RNA interference [45], to ascertain the functions of these genes.

5. in silico markers

We identified a total of 208 in silico microsatellites among the 29,745 unique EST sequences. Most microsatellites were dinucleotide repeats (158) followed by trinucleotides (22) (Table 6 and Additional File 2 for more details). Of the 208 EST-containing microsatellites, only 25 (12%) have significant matches with available ESTs in the NCBI non redundant database whereas 173 (83.2%) have sufficient flanking sequences for primer design. From these, we have recently developed 18 microsatellite markers [22] and have successfully used them for genetic linkage mapping and QTL analysis. Many potentially-useful microsatellites, identified in silico, still need to be developed to become useful polymorphic markers for comparative mapping, marker-assisted selection, and evolutionary studies [46]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have recently become the marker type of choice for linkage and QTL analysis [47]. In most cases, SNPs have relied upon genomic sequencing, BAC end sequencing, or targeted SNP detection. We identified a total of 7,530 putative SNPs, including 1,344 non-synonymous and 5,097 synonymous mutations, and 1,089 indels (Table 7). These SNPs represent an average of 1 SNP per 75 base pairs, slightly lower than the previously-reported frequency of one SNP every 60 base pairs in coding regions [19,48], but higher than in C. virginica, with one SNP for every 170 base pairs [49]. These SNPs will also be useful for linkage mapping and population-level studies, and a few to detect selective effects in coding regions of genes regulated by environmental factors. To provide some assessment of the SNPs, the putative SNPs were categorized based upon contig sizes. As mentioned in a previous report [49], the larger the number of sequences involved in a contig, the more likely the SNP can be checked as to whether the putative SNPs represent sequence errors or real SNPs. As shown in Table 8, 2,077 putative SNPs were identified from contigs with only two sequences; 1,358 putative SNPs were identified from contigs with three sequences; 1,044 putative SNPs were identified from contigs with four sequences, and 3,051 putative SNPs were identified from contigs with five or more sequences (Table 8). Consequently, validation and polymorphism analyses must be performed before these putative SNPs can be used because a large proportion of SNPs were identified from contigs with just a few sequences and may be sequencing errors.

Table 6.

in silico microsatellite (Msat) mining of the GigasDatabase.

| Number of Msat | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 208 | 100 |

| Dinucleotide | 158 | 76.0 |

| Trinucleotide | 22 | 10.6 |

| Tetranucleotide | 18 | 8.7 |

| Pentanucleotide | 10 | 4.8 |

Percentage represents the percentage of each kind of repeated motif.

Table 7.

Putative Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) identification from the GigasDatabase.

| SNP Type | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Non Synonymous | 1344 | 17.85 |

| Synonymous | 5097 | 67.69 |

| Indel | 1089 | 14.46 |

| Total | 7530 | 100 |

| A/G | 1860 | 36.49 |

| T/C | 1494 | 29.31 |

| A/C | 551 | 10.81 |

| A/T | 284 | 5.57 |

| T/G | 381 | 7.47 |

| G/C | 518 | 10.16 |

| TriNucleotides | 9 | 0.19 |

| Total | 7530 | 100 |

Indels are Insertions and Deletions detected in the sequences with a range of 1 to 13 bases

Two distinct subcategories of SNP have been identified:

- Transition (ts) e.g. A⇔G; T⇔C that are mutations between two puric bases (A/G) or between two pyrimidic bases (C/T)

- Transversion (tv) e.g. A⇔C; A⇔T; T⇔G; G⇔C that are mutations between puric and pyrimidic bases

Trinucleotides are polymorphic sites that show three alleles at the same locus.

Table 8.

Putative SNP distribution in contigs with various number of ESTs.

| Number of contigs | Putative SNP sites | |

|---|---|---|

| with > 50 sequences | 24 | 432 |

| with 11–50 sequences | 433 | 721 |

| with 6–10 sequences | 1352 | 1663 |

| with 5 sequences | 647 | 235 |

| with 4 sequences | 1753 | 1044 |

| with 3 sequences | 1145 | 1358 |

| with 2 sequences | 2586 | 2077 |

| Total | 7940 | 7530 |

Conclusion

In the present paper, we report the production and the sequencing of clones from 9 cDNA libraries derived from different C. gigas tissues, and from oysters sampled under different conditions, obtaining 40,845 high-quality ESTs that identify 29,745 unique transcribed sequences. Putative annotation was assigned to 43% of the sequences showing similarity to known genes, mostly from other species, in one or more of the databases used for automatic annotation. The high percentage of C. gigas ESTs (57%) with no hits in the protein database implies that there is an enormous potential for discovery of new genes in this species, and possibly new gene networks and metabolic pathways. All data on ESTs, clustering, and annotation can be accessed from the dedicated database, GigasDatabase, available at http://public-contigbrowser.sigenae.org:9090/Crassostrea_gigas/index.html. There is a variety of data-access options, such as database searches on annotation including gene assignments and GO terms, as well as access to self-explanatory, web-based detail annotation archive. This large set of well-characterized clones represents a significant addition to the existing genomic resources for oysters. Indeed, Crassostrea gigas, which belongs to the Lophotrochozoans, a large but understudied clade of bilaterian animals, represents a rare non-model species for which the genomic resources available will be very important. Several research teams are now using this important sequence information to examine oyster gene-expression profiles under various experimental and environmental conditions.

Availability and requirements

Project name: the GigasDatabase.

The Oyster EST contig browser aimed to produce and maintain an automatic annotation of Oyster EST libraries established in three consecutive projects, the Marine Genomics Network of Excellence, the European AquaFirst project and the Crassostrea gigas Genoscope project.

The Project home page is: http://public-contigbrowser.sigenae.org:9090/Crassostrea_gigas/index.html

Operating system: LINUX.

Programming language: Perl 5.8.

Other requirements: MySQL 5 or higher, Apache 2.

Licence: Apache like License (free software license with no copyleft).

Any restrictions to use by non-academics: no.

Authors' contributions

EF, PF, CL, PB and AH assisted in data acquisition and analysis. AH, JS, PL, CF, DG, AT, DM, JM, VB, JdL, YG and EB prepared the biological material and did the construction of the libraries. RR, FG and PW were in charge of the sequencing. FM worked on software design, carried out development, implementation and data processing and CK supervised the web design. CS and SL worked on the detection of in silico markers. MM and PP coordinated the involved projects. EF, PF, CL, PB and AH were involved in drafting the manuscript and JM, CC, PP, MM, Sl, GD, PL, JdL, YG and VB revised it for important content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

List of C. gigas annotated sequences. This table lists 12790 non-redundant sequences identifying known C. gigas sequences showing significant similarity (E-value < 10-6) with predicted proteins from mollusks and other organisms. This table includes the GenBank Accession numbers of the ESTs and corresponding best SwissProt hit descriptions.

in silico microsatellites in C. gigas ESTs. This table lists the 208 ESTs containing in silico microsatellites with, for each sequence, the corresponding motif, the number of repeats, the start and the end position, and the sequence of the in silico microsatellite.

Contributor Information

Elodie Fleury, Email: efleury@ifremer.fr.

Arnaud Huvet, Email: ahuvet@ifremer.fr.

Christophe Lelong, Email: christophe.lelong@unicaen.fr.

Julien de Lorgeril, Email: Julien.De.Lorgeril@ifremer.fr.

Viviane Boulo, Email: Viviane.Boulo@ifremer.fr.

Yannick Gueguen, Email: Yannick.Gueguen@ifremer.fr.

Evelyne Bachère, Email: Evelyne.Bachere@ifremer.fr.

Arnaud Tanguy, Email: atanguy@sb-roscoff.fr.

Dario Moraga, Email: Dario.Moraga@univ-brest.fr.

Caroline Fabioux, Email: fabioux@univ-brest.fr.

Penelope Lindeque, Email: PKW@pml.ac.uk.

Jenny Shaw, Email: JENS@pml.ac.uk.

Richard Reinhardt, Email: rr@molgen.mpg.de.

Patrick Prunet, Email: prunet@rennes.inra.fr.

Grace Davey, Email: grace.davey@nuigalway.ie.

Sylvie Lapègue, Email: Sylvie.Lapegue@ifremer.fr.

Christopher Sauvage, Email: Christopher.Sauvage@ifremer.fr.

Charlotte Corporeau, Email: Charlotte.Corporeau@ifremer.fr.

Jeanne Moal, Email: Jeanne.Moal@ifremer.fr.

Frederick Gavory, Email: fgavory@genoscope.cns.fr.

Patrick Wincker, Email: pwincker@genoscope.cns.fr.

François Moreews, Email: fmoreews@irisa.fr.

Christophe Klopp, Email: Christophe.Klopp@toulouse.inra.fr.

Michel Mathieu, Email: michel.mathieu@unicaen.fr.

Pierre Boudry, Email: Pierre.Boudry@ifremer.fr.

Pascal Favrel, Email: pascal.favrel@unicaen.fr.

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this paper was performed within the framework of several research projects funded by: Genoscope (11/AP2006-2007), Marine Genomics Network of Excellence (GOCE-CT-2004-505403), the European project "Aquafirst" (513692) in the Sixth Framework Program, ANR "CgPhysiogène" (ANR-06-GANI-009) and "Gametogenes" (ANR-08-GENM-041).

All sequence analyses were conducted in collaboration with the SIGENAE bioinformatics team. Specific requests for EST sequence chromatograms should be addressed at sigenaesupport@jouy.inra.fr.

We thank G. Wikfors for his help for editing the English language. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

References

- Hubert S, Hedgecock D. Linkage maps of microsatellite DNA markers for the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas . Genetics. 2004;168(1):351–362. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.027342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Guo X. AFLP-based genetic linkage maps of the pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793) Mar Biotechnol. 2004;6(1):26–36. doi: 10.1007/s10126-003-0001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C, Hikima J, Jenny MJ, Chapman RW, Fang GC, Saski C, Lundqvist ML, Wing RA, Cupit PM, Gross PS. et al. New resources for marine genomics: bacterial artificial chromosome libraries for the Eastern and Pacific oysters (Crassostrea virginica and C. gigas) Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2006;8(5):521–533. doi: 10.1007/s10126-006-6013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillen DJ, Chen YA, Chen C, Jenny MJ, Trent HF 3rd, Robalino J, McLean DC Jr, Gross PS, Chapman RW, Warr GW. et al. Marine genomics: a clearing-house for genomic and transcriptomic data of marine organisms. BMC Genomics. 2005;6(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra C, Bachère E. Bivalve genomics. Aquaculture. 2006;256(1–4):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D, Lin JZ, DeCola S, Haudenschild CD, Meyer E, Manahan DT, Bowen B. Transcriptomic analysis of growth heterosis in larval Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(7):2313–2318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610880104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny MJ, Chapman RW, Mancia A, Chen YA, McKillen DJ, Trent H, Lang P, Escoubas JM, Bachere E, Boulo V. et al. A cDNA microarray for Crassostrea virginica and C. gigas. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2007;9(5):577–591. doi: 10.1007/s10126-007-9041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruesink JL, Lenihan HS, Trimble AC, Heiman KW, Micheli F, Byers JE, Kay MC. Introduction of non-native oysters: Ecosystem effects and restoration implications. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2005;36:643–689. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102003.152638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bachere E, Gueguen Y, Gonzalez M, de Lorgeril J, Garnier J, Romestand B. Insights into the anti-microbial defense of marine invertebrates: the penaeid shrimps and the oyster Crassostrea gigas . Immunol Rev. 2004;198:149–168. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badariotti F, Lelong C, Dubos MP, Favrel P. Characterization of chitinase-like proteins (Cg-Clp1 and Cg-Clp2) involved in immune defence of the mollusc Crassostrea gigas . Febs J. 2007;274(14):3646–3654. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelong C, Badariotti F, Le Quere H, Rodet F, Dubos MP, Favrel P. Cg-TGF-beta, a TGF-beta/activin homologue in the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas, is involved in immunity against Gram-negative microbial infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2007;31(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney PM, Bushek D. Genetic aspects of disease resistance in oysters. Journal of Shellfish research. 1996;15:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Samain JF, Dégremont L, Soletchnik P, Haure J, Bédier E, Ropert M, Moal J, Huvet A, Bacca H, Van Wormhoudt A. et al. Genetically based resistance to summer mortality in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) and its relationship with physiological, immunological characteristics and infection process. Aquaculture. 2007;268(1–4):227–243. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.04.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huvet A, Herpin A, Degremont L, Labreuche Y, Samain JF, Cunningham C. The identification of genes from the oyster Crassostrea gigas that are differentially expressed in progeny exhibiting opposed susceptibility to summer mortality. Gene. 2004;343(1):211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguy A, Boutet I, Laroche J, Moraga D. Molecular identification and expression study of differentially regulated genes in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in response to pesticide exposure. Febs J. 2005;272(2):390–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2004.04479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badariotti F, Kypriotou M, Lelong C, Dubos MP, Renard E, Galera P, Favrel P. The phylogenetically conserved molluscan chitinase-like protein 1 (Cg-Clp1), homologue of human HC-gp39, stimulates proliferation and regulates synthesis of extracellular matrix components of mammalian chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):29583–29596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleury E, Fabioux C, Lelong C, Favrel P, Huvet A. Characterization of a gonad-specific transforming growth factor-beta superfamily member differentially expressed during the reproductive cycle of the oyster Crassostrea gigas . Gene. 2008;410(1):187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xu Z, Guo X. Differences in the rDNA-bearing chromosome divide the Asian-Pacific and Atlantic species of Crassostrea (Bivalvia, Mollusca) Biol Bull. 2004;206(1):46–54. doi: 10.2307/1543197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage C, Bierne N, Lapegue S, Boudry P. Single Nucleotide polymorphisms and their relationship to codon usage bias in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas . Gene. 2007;406(1–2):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Flores I, de la Herran R, Garrido-Ramos MA, Boudry P, Ruiz-Rejon C, Ruiz-Rejon M. The molecular phylogeny of oysters based on a satellite DNA related to transposons. Gene. 2004;339:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang RP, Bayne CJ, Camara MD, Cunningham C, Jenny MJ, Langdon CJ. Transcriptome profiling of selectively bred Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas families that differ in tolerance of heat shock. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2009. in press . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sauvage C, Boudry P, Lapegue S. Identification and characterization of 18 novel polymorphic microsatellite makers derived from expressed sequence tags in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9:853–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Obst M, Wilson K, Sköld H, Nakano H, Thorndyke MC. Marine Ecological Genomics – When Genomics meet Marine Ecology. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2007;332:257–273. doi: 10.3354/meps332257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguy A, Bierne N, Saavedra C, Pina B, Bachere E, Kube M, Bazin E, Bonhomme F, Boudry P, Boulo V. et al. Increasing genomic information in bivalves through new EST collections in four species: development of new genetic markers for environmental studies and genome evolution. Gene. 2008;408(1–2):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samain JF, McCombie H. Summer mortality of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. The Morest Project. Versailles: Ed Quae. 2008. p. 379.

- Gueguen Y, Cadoret JP, Flament D, Barreau-Roumiguiere C, Girardot AL, Garnier J, Hoareau A, Bachere E, Escoubas JM. Immune gene discovery by expressed sequence tags generated from hemocytes of the bacteria-challenged oyster, Crassostrea gigas . Gene. 2003;303:139–145. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D, Gaffney PM, Goulletquer P, Guo X, Reece K, Warr GW. The case for sequencing the Pacific oyster genome. Journal of Shellfish research. 2005;24(2):429–441. [Google Scholar]

- Fabioux C, Huvet A, Lelong C, Robert R, Pouvreau S, Daniel JY, Minguant C, Le Pennec M. Oyster vasa-like gene as a marker of the germline cell development in Crassostrea gigas . Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320(2):592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhulidov PA, Bogdanova EA, Shcheglov AS, Vagner LL, Khaspekov GL, Kozhemyako VB, Matz MV, Meleshkevitch E, Moroz LL, Lukyanov SA. et al. Simple cDNA normalization using kamchatka crab duplex-specific nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(3):e37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet A, Iannuccelli E, Hugot K, Benne F, Bonaldo MF, Soares MB, Hatey F, Tosser-Klopp G. A pig multi-tissue normalised cDNA library: large-scale sequencing, cluster analysis and 9K micro-array resource generation. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. 2000;7(1–2):203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Madan A. CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999;9(9):868–877. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.9.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007. pp. W182–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(19):3787–3793. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungis D, Berube Y, Zhang J, Ralph S, Ritland CE, Ellis BE, Douglas C, Bohlmann J, Ritland K. Robust simple sequence repeat markers for spruce (Picea spp.) from expressed sequence tags. Theor Appl Genet. 2004;109(6):1283–1294. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde L, Vaquerizas JM, Dopazo H, Arbiza L, Reumers J, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Dopazo J. PupaSuite: finding functional single nucleotide polymorphisms for large-scale genotyping purposes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006. pp. 621–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Herpin A, Lelong C, Becker T, Rosa F, Favrel P, Cunningham C. Structural and functional evidence for a singular repertoire of BMP receptor signal transducing proteins in the lophotrochozoan Crassostrea gigas suggests a shared ancestral BMP/activin pathway. Febs J. 2005;272(13):3424–3440. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelong C, Mathieu M, Favrel P. Structure and expression of mGDF, a new member of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily in the bivalve mollusc Crassostrea gigas . Eur J Biochem. 2000;267(13):3986–3993. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JE. Energy balance and reproduction. Physiol Behav. 2004;81(2):289–317. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JE. Metabolic and hormonal control of the desire for food and sex: implications for obesity and eating disorders. Horm Behav. 2006;50(4):562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Fernandez R, Martini AC, Navarro VM, Castellano JM, Dieguez C, Aguilar E, Pinilla L, Tena-Sempere M. Novel signals for the integration of energy balance and reproduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254–255:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade GN, Jones JE. Neuroendocrinology of nutritional infertility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(6):R1277–1296. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00475.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagnani C, Labreuche Y, Escoubas JM. Cg-IkappaB, a new member of the IkappaB protein family characterized in the pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas . Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32(3):182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabioux C, Corporeau C, Quillien V, Favrel P, Huvet A. In vivo RNA interference in oyster: vasa silencing inhibits germ cell development. FEBS Journal. 2009;276:2566–2573. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Li Q. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of EST-SSRs in the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) J Hered. 2008;99(2):208–214. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esm124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafalski A. Applications of single nucleotide polymorphisms in crop genetics. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curole JP, Hedgecock D. Estimation of preferential pairing rates in second-generation autotetraploid pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) Genetics. 2005;171(2):855–859. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilang J, Wang S, Li P, Abernathy J, Peatman E, Wang Y, Wang L, Shi Y, Wallace R, Guo X. et al. Generation and analysis of ESTs from the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica Gmelin and identification of microsatellite and SNP markers. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of C. gigas annotated sequences. This table lists 12790 non-redundant sequences identifying known C. gigas sequences showing significant similarity (E-value < 10-6) with predicted proteins from mollusks and other organisms. This table includes the GenBank Accession numbers of the ESTs and corresponding best SwissProt hit descriptions.

in silico microsatellites in C. gigas ESTs. This table lists the 208 ESTs containing in silico microsatellites with, for each sequence, the corresponding motif, the number of repeats, the start and the end position, and the sequence of the in silico microsatellite.