Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To visualize human prostate cancer cells in mouse bone with bioconjugated near-infrared quantum dot (QD) probes. Near-infrared fluorescent probes using QDs can visualize tumors in deep tissues in vivo.

METHODS

Human prostate cancer C4-2B xenografts grown in mouse tibia were detected by prostate-specific membrane antigen antibody conjugated with QDs emitting light at the near-infrared range of 800 nm (QD800). Images in culture and in vivo were acquired using the IVIS Imaging System.

RESULTS

As few as 5000 cells can be detected subcutaneously when tagged with QD800 conjugate and injected directly into mice. QD800 conjugate injected intravenously in mice harboring C4-2B tumors in tibia detected signals from a minimum of 500 000 cells. The maximal light emission was detected 30 minutes after intravenous injection of QD800 conjugate in mice with established C4-2B tumors.

CONCLUSIONS

Bioconjugated near-infrared QD probes are highly sensitive molecular imaging tools for human prostate cancer micrometastases in mice.

Fluorescent semiconductor nanocrystals (quantum dots [QDs]) have unique optical and chemical features suited for biomedical imaging.1 QDs conjugated to antibodies,2–4 peptides,5–8 RNA aptamer,9 or other targeting ligands10,11 can track and target local tumor growth, distant metastasis, tumor-associated neovasculature, and apoptotic cell death in live subjects. Their superior optical properties include intense fluorescent signals with sharp and narrow spectra,12,13 improved optical stability, and a tunable ability to emit fluorescent signals for a wide range of spectra. QDs can enable tracking of the movement of molecules within a single cell.14 Clinically, multiplexing QDs might enable personalized treatment.15,16 QD technology can be tailored to image and target tumor cells2,16 and their microenvironment5,8 by conjugating cell-surface ligands to QDs, along with a therapeutic drug17 and a sensing probe to detect apoptosis.18

QDs with visible light emission in the 655-nm range conjugated with anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) antibody (QD655) can detect subcutaneous human prostate tumor xenografts grown in mice.19 QD655, however, has suboptimal tissue penetration and autofluorescence from the skin.19 To improve this approach, we used an anti-PSMA antibody conjugate with QDs that emit light in the near-infrared (NIR) 800-nm range (QD800). QD800 is superior and more sensitive than QD655 for detecting human C4-2 and C4-2B prostate tumors in mouse tibia19 and is not compromised by autofluorescence interference.20,21

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bioconjugation of QDs

QDs (Qdot 800 nanocrystals) with an emission peak of 800 nm were purchased from Quantum Dot (Hayward, CA) and conjugated to a J591 monoclonal antibody (Millennium Pharmaceutical, Cambridge, MA) recognizing PSMA, a human prostate cancer (PCa) cell-surface antigen. Bioconjugation was performed with a Qdot 800 Antibody Conjugation Kit (Quantum Dot). QDs with or without polyethylene glycol modification were activated using the hetero-bifunctional cross-linker 4-(maleimidomethyl)-1-cyclohexanecarboxylic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (SMCC), yielding a maleimide-nanocrystal surface. PSMA monoclonal antibody J591 was reduced with dithiothreitol to expose free sulfhydryl functional groups. Excess SMCC and dithiothreitol were removed by size exclusion chromatography. Activated Qdot 800 polyethylene glycol conjugates were mixed with the reduced J591 at a ratio of 1:3 and then covalently coupled. The reaction was quenched with β-mercaptoethanol. The resultant QD800 conjugates were concentrated by ultrafiltration and purified using size exclusion chromatography.

Fluorescent Imaging of Cells and Mice

Cultured PCa cells on chamber slides were prepared and examined under an inverted Olympus microscope (IX-70) equipped with a digital color camera (Nikon D1, Nikon, Northvale, NJ), a broad-band light source (ultraviolet 330–385 nm and blue 460–500 nm), and long-pass interference filters (DM 400 and 510, Chroma Tech, Rockingham, VT). The 800-nm light emission was detected by a fluorescence spectrum using a singlestage spectrophotometer (SpectraPro 150, Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ) and WinSpec 32 software (Roper Scientific).

For in vivo imaging, a sequence of images taken with narrow band emission filters was used to subtract the tissue autofluorescence background. Imaging was performed at different points after injection using the IVIS Imaging System 100 Series (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA), with excitation of 710–760 nm, background filter excitation of 665–695 nm, and emission of 810–875 nm. The image was displayed in real physical units of surface radiance (photons/s/cm2/sr). The minimal detectability for the instrument was specified at <100 photons/s/cm2/sr for a 5-minute exposure and binning of 10.22 The tumor signal-to-noise ratio was calculated by taking the signal from the tumor side and control background side of the mouse with the same area and orientation. After whole body imaging, the mice were killed by a carbon dioxide overdose. The tumor and major organs were removed and frozen for histologic study.

Cell Culture, Tissue Processing, and Whole Animal Studies

Both PSMA-positive C4-2B (a bone metastatic LNCaP-derived subline) and negative (PC3) human PCa cells were used. The cell lines were maintained in T medium (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) with 5% fetal bovine serum.23 Conventional immunohistochemical procedures were used to determine the binding of QD800 to C4-2B cells, with either unconjugated QD (no antibody) or PC3 cells (no PSMA) as negative controls. C4-2B or PC3 cells were cultured for 2–3 days, harvested, washed, fixed, and stained on chamber slides using an established immunohistochemical protocol. The cells were incubated with QD800 (20 nM) for 1 hour at 4°C to minimize the internalization process, then washed and subjected to QD surface-binding analysis under a spectrophotometer. The phase contrast morphology of the cells was photographed. The tumor cells were injected into nude mice 4–6 weeks old subcutaneously or intratibially under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University. To prepare the QD800-tagged cells, the C4-2B cells were incubated with 20 nM QD800, a QD-anti-PSMA antibody conjugate for 4 hours, washed, and used for injection at a subcutaneous, intratibial, or tail vein site for the in vivo studies. In separate studies, QD800 was injected at a dose of 100 pmol in 100 μL phosphate-buffered saline by way of the tail vein in mice 2 hours after the C4-2B cells were injected. The C4-2B cells were also allowed to form a solid tumor mass for 4 weeks before QD800 administration. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine (95, 10, and 2 mg/kg, respectively). To decrease autofluorescence, a special alfalfa-free diet (TD97185 nonirradiated, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) was used during the entire experimental period. Images were taken at different points after QD800 injection.

Statistical Analysis

The values are expressed as the mean ± SE of 3 independent repeated experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test, with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

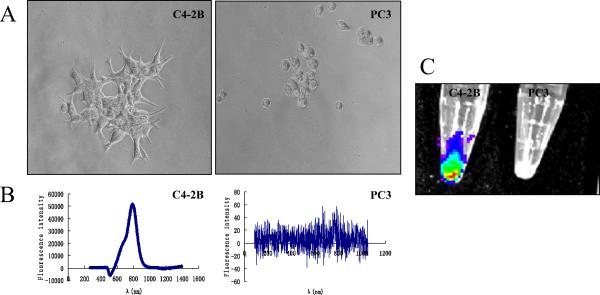

QD800 Binding in Human PCa Cells

The binding of QD800 to PSMA-positive C4-2B and negative PC3 cells was measured by a fluorescence spectrophotometer under a microscope. Figure 1 shows a phase contrast (Fig. 1A) image of the positive binding of QD800 (Fig. 1B), with the expected maximal luminescence of 800 nm in C4-2B but not PC3 cells. Control studies using QDs without antibody conjugation showed no background binding to C4-2B cells (data not shown). Positive binding of QD800 to C4-2B but not PC3 cells was also apparent under Xenogen IVIS Imaging System fluorescence imaging (Fig. 1C). QD800 showed no obvious toxicity to cell morphology, proliferation, or viability under our in vitro culture conditions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Immunocytochemistry of quantum dot (QD)800 binding activity in cultured prostate cancer (PCa) cells. (A) Phase contrast of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-positive C4-2B cells and PSMA-negative PC3 cells in culture. (B) Spectrophotometry analysis of positive binding of QD800 conjugates on surface of PSMA-positive C4-2B cells. Negative staining in PC3 cells, which lacked PSMA expression. (C) Positive binding of C4-2B cells to QD800 in cell pellet. Control PC3 cells did not bind to probe (Xenogen IVIS Imaging System).

Detection of QD800-tagged C4-2B Cells in Mice

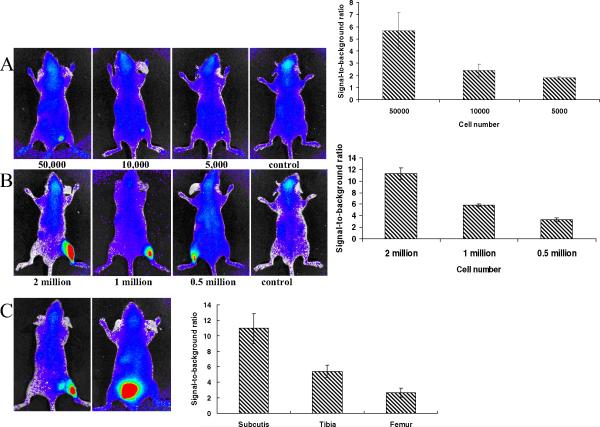

The background autofluorescence signal was reduced by feeding mice with alfalfa-free food (Harlan Teklad; data not shown). The C4-2B cells were tagged with QD800, washed, and injected subcutaneously or intratibially into live mice. A cell number-dependent increase in fluorescence intensity was observed at both subcutaneous (Fig. 2A) and intratibial (Fig. 2B) sites at 5000 and 500 000 cells, respectively. Overall, the fluorescence intensity of 1 × 106 QD800-tagged C4-2B cells was lower at the intrafemural and intratibial sites than at the subcutaneous sites because deeper light penetration was required for the bone sites (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Fluorescent images and signal-to-background ratio of quantum dot (QD)800 tagged C4-2B cells at (A) subcutaneous or (B) intratibial sites to establish minimal number of cells that could be detected by fluorescent imaging. (C) One million QD800-tagged C4-2B cells injected at different sites show effects of tissue depth on fluorescent signal. F, femur; T, tibia; S, subcutis. C4-2B cells previously tagged with QD800 inoculated subcutaneously or intraosseously. Data collected from 3 mice for each group with specific cell number of cancer cells.

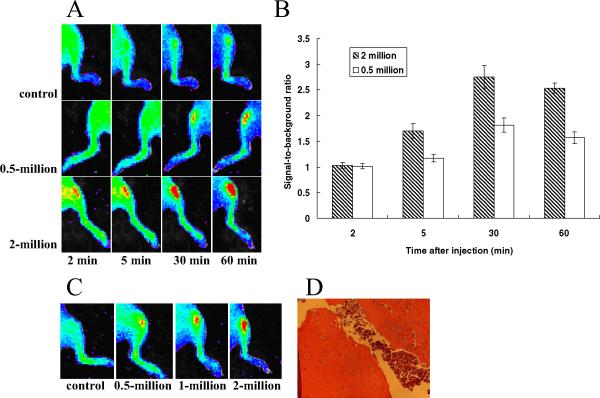

In Vivo Imaging of Human PCa in Mouse Tibia

PCa cells in mouse tibia were imaged using 2 methods. First, the PCa cells were directly injected into mouse tibia before QD800 administration, and second, the PCa cells were allowed to form a solid tumor mass for 4 weeks before QD800 administration. QD800 (100 pmol/mouse) administered through the tail vein could be readily seen in the superficial vasculature space within <2 minutes (Figure 3A). Tumor cells injected at >2 × 106 cells could be detected as early as 2 minutes after QD800 injection. The lower limit of detectability in the mouse tibia was estimated at 0.5 × 106 cells, with a clearly detectable signal at 10 minutes. The fluorescence signal intensity reached a maximal tumor-to-background ratio within 30 minutes (Fig. 3B). To test QD800 against pre-established tumors in the mouse tibia, we inoculated C4-2B cells at different cell numbers into mouse tibia. After 4 weeks, radiography, serum prostate-specific antigen measurement, or pathologic observation confirmed the presence of established tumors (data not shown). We observed a fluorescent signal 30 minutes after tail vein administration of QD800 (Fig. 3C). The histologic features of the C4-2B cells grown in mouse tibia with a 1 million cell injection are shown in Figure 3D. No significant fluorescence signal was detected after injecting unconjugated QDs (control).

Figure 3.

In vivo near-infrared (NIR) fluorescent images of C4-2B cell-bearing mice. (A) Quantum dot (QD)800 conjugates given by tail vein to mice after inoculating 0.5 million or 2 million C4-2B cells. Control mice received no C4-2B cells. Images taken 2 hours after injection. (B) Tumor-to-background ratio of mice injected with QD800 conjugates. (C) QD800 conjugates given by tail vein to mice with established (4-week) tibial tumors. (D) Histologic features of C4-2B cells grown in mouse tibia. Data collected from 3 mice from each group.

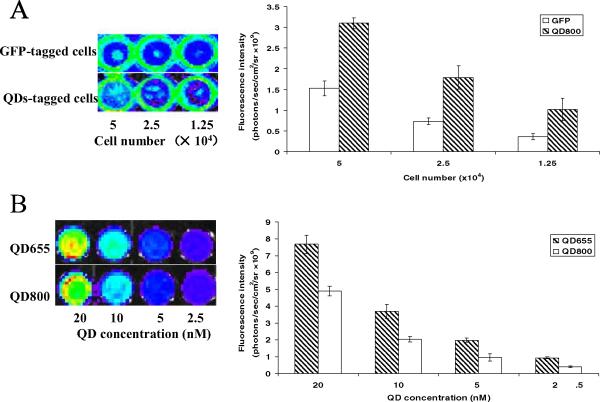

Comparison of Images From QD800- or QD655-tagged C4-2B Cells and Green Fluorescent Protein Stably Transfected C4-2B Cells

The in vitro fluorescence intensity of QD800-tagged PCa cells was about twice that from green fluorescent protein stably transfected C4-2B cells (Fig. 4A). A total of 50 000 QD800-tagged C4-2B cells could be clearly seen. A similar number of C4-2B cells stably transfected with green fluorescent protein produced no detectable signal when directly injected into the mice (data not shown). We also compared the fluorescence intensity of NIR QD800- and visible QD655-tagged C4-2B cells. The fluorescence intensity of QD655 was comparable to that of QD800 in vitro (Fig. 4B), but QD655 injected by way of the tail vein produced no significant signal owing to low tissue penetration (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(A) Comparison of fluorescent images and signal intensity of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged and quantum dot (QD)800-tagged C4-2B cells in vitro. (B) Comparison of fluorescent images and signal intensity of QD655- and QD800-tagged C4-2B cells in vitro. Data collected from 3 independent repeats for each group.

COMMENT

Sensitive methods to detect localized and metastatic PCa are urgently needed. NIR QDs conjugated with an antibody against PSMA (QD800) proved superior to QD655 and green fluorescent protein for detecting PCa cells in subcutaneous and intratibial sites in mice with no detectable interfering autofluorescence. As few as 5000 QD800 pretagged PCa cells were detected subcutaneously. QD800 injected by way of the tail vein detected as few as 500 000 cells at subcutaneous or intratibial sites. QD800 accumulated maximally in intratibial sites within 30 minutes after tail vein administration. The QD800 images could be detected <1 hour after tail vein administration. Because this method can detect ~500 000 cells or ~0.5-mg tumor tissue mass of pre-established C4-2B tumors, this represents an approximately 1000-fold better sensitivity than other currently available technologies (~0.5 g).

Cai et al.8 imaged tumor vasculature with arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) peptide-labeled NIR QDs with the light emission at 705 nm. Kim et al.21 imaged sentinel lymph nodes 1 cm deep in tissues by direct injection of NIR QDs emitting light at 850 nm. Our work further illustrates the potential of NIR QDs to detect cancer and metastasis. The fluorescent spectra in the NIR region are broad (700–1400 nm) and distant from the typical spectrum of tissue autofluorescence (400–600 nm). Multifunctional particles using NIR QDs with different targets might be able to image cancer cells and their microenvironment in vivo for real-time monitoring of apoptosis, angiogenesis, and inflammation. QDs conjugated to drug payloads could enable simultaneous cancer diagnosis and treatment.16

Toxicity remains a concern, but current studies have detected no acute or obvious cadmium-selenium QD toxicity when properly capped by both zinc sulfide and hydrophilic shells.19,21,24–26 The doses of QDs needed for in vivo use are less than the known toxicity levels for toxic QD core materials such as cadmium.21 In the present study, only 100 pmol was given to each mouse, and no toxic effects were observed.

Future challenges for NIR QDs include (a) stable and robust coating strategies to reduce potential toxicity or alternatively, nontoxic QD materials such as copper or manganese-doped zinc-selenium QDs with a relatively narrow full-width half maximum and acceptable quantum efficiency27 or nonheavy-metal semiconductor materials such as indium gallium phosphide QDs28; (b) improving the brightness of QDs to increase the detection sensitivity; (c) choosing suitable QD sizes and external coating materials to reduce nonspecific uptake and retention by the reticular endothelial system in the liver and spleen; and (d) the conjugation of QDs with biomolecules or organic molecules as targeted ligands to increase the sensitivity and specificity of tumor-specific targeting.

Acknowledgment

To Xiaohu Gao for technical help and discussion, Millennium Pharmaceuticals for providing the PSMA monoclonal antibody (J591), and Gary Mawyer for editing.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (grant P01 CA098912 to L. W. K. Chung and grants R01 GM60562 and RO1 CA108468 to S. Nie), Department of Defense (grant 17-03-2-0033 to L. W. K. Chung), Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scholar Awards (L. W. K. Chung and S. Nie); and in part by grants NKBRP2005CB522605, SKLZZ200810, NFSC30400188, FANEDD200777, IRT0712, and CSTC2008BB5023 from China (C. Shi and Y. Su).

References

- 1.Choy G, Choyke P, Libutti SK. Current advances in molecular imaging: noninvasive in vivo bioluminescent and fluorescent optical imaging in cancer research. Mol Imaging. 2003;2:303–312. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu X, Liu H, Liu J, et al. Immunofluorescent labeling of cancer marker Her2 and other cellular targets with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nbt764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan WC, Nie S. Quantum dot bioconjugates for ultrasensitive nonisotopic detection. Science. 1998;281:2016–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaiswal JK, Mattoussi H, Mauro JM, et al. Long-term multiple color imaging of live cells using quantum dot bioconjugates. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:47–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akerman ME, Chan WC, Laakkonen P, et al. Nanocrystal targeting in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12617–12621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152463399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winter JO, Liu TY, Korgel BA, et al. Recognition molecule directed interfacing between semiconductor quantum dots and nerve cells. Adv Mater. 2001;13:1673–1677. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinaud F, King D, Moore HP, et al. Bioactivation and cell targeting of semiconductor CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals with phytochelatin-related peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6115–6123. doi: 10.1021/ja031691c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai W, Shin DW, Chen K, et al. Peptide-labeled near-infrared quantum dots for imaging tumor vasculature in living subjects. Nano Lett. 2006;6:669–676. doi: 10.1021/nl052405t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu TC, Marks JW, Lavery LA, et al. Aptamer:toxin conjugates that specifically target prostate tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5898–5892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerion D, Parak WJ, Williams SC, et al. Sorting fluorescent nanocrystals with DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7070–7074. doi: 10.1021/ja017822w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan P, Yuen T, Ruf F, et al. Method for multiplex cellular detection of mRNAs using quantum dot fluorescent in situ hybridization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e161. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X, Yang L, Petros JA, et al. In vivo molecular and cellular imaging with quantum dots. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2005;16:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain KK. Role of nanobiotechnology in developing personalized medicine for cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2005;4:645–650. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yezhelyev MV, Gao X, Xing Y, et al. Emerging use of nanoparticles in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:657–667. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70793-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Vlerken LE, Amiji MM. Multi-functional polymeric nanoparticles for tumour-targeted drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2006;3:205–216. doi: 10.1517/17425247.3.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Gac S, Vermes I, van den Berg A. Quantum dots based probes conjugated to annexin V for photostable apoptosis detection and imaging. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1863–1869. doi: 10.1021/nl060694v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, et al. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu A, Gu W, Larabell C, et al. Semiconductor nanocrystals for biological imaging. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Lim YT, Soltesz EG, et al. Near-infrared fluorescent type II quantum dots for sentinel lymph node mapping. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nbt920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Troy T, Jekic-McMullen D, Sambucetti L, et al. Quantitative comparison of the sensitivity of detection of fluorescent and bioluminescent reporters in animal models. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:9–23. doi: 10.1162/15353500200403196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gleave M, Hsieh JT, Gao CA, et al. Acceleration of human prostate cancer growth in vivo by factors produced by prostate and bone fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3753–3761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardman R. A toxicologic review of quantum dots: toxicity depends on physicochemical and environmental factors. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:165–172. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter JO, Liu TY, Korgel BA, et al. Recognition molecule directed interfacing between semiconductor quantum dots and nerve cells. Adv Mater. 2001;13:1673–1677. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson DR, Zipfel WR, Williams RM, et al. Water-soluble quantum dots for multiphoton fluorescence imaging in vivo. Science. 2003;300:1434–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1083780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pradhan N, Goorskey D, Thessing J, et al. An alternative of CdSe nanocrystal emitters: pure and tunable impurity emissions in ZnSe nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17586–17587. doi: 10.1021/ja055557z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinaud F, Michalet X, Bentolila LA, et al. Advances in fluorescence imaging with quantum dot bio-probes. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1679–1687. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]