Abstract

Objectives

To demonstrate achievement of ability-based outcomes through a structured review of electronic student portfolios in an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) program.

Design

One hundred thirty-eight students produced electronic portfolios containing select work products from APPEs, including a self-assessment reflective essay that demonstrated achievement of course manual-specified ability-based outcomes.

Assessment

Through portfolio submissions, all students demonstrated the achievement of ability-based outcomes for providing pharmaceutical care, evaluating the literature, and managing the medication use system with patient case reports most frequently submitted. The rubric review of self-reflective essays addressed student learning through APPEs and continuing professional development plans.

Conclusion

The electronic portfolio with reflective essay proved to be a useful vehicle to demonstrate achievement of ability-based outcomes.

Keywords: electronic reflective portfolio, APPE evaluation, assessment rubric, ability-based outcomes, standards 2007

INTRODUCTION

The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) stipulates in Guideline 15.1 of Accreditation Standards 2007 that colleges and schools of pharmacy should use student portfolios as a means to document student progress and achievement of desired competencies, measured in a variety of health care settings during pharmacy practice experiences. Further, Guideline 15.4 adds that the student portfolio should be standardized and include components of student self-assessment and preceptor assessments of educational outcomes.1

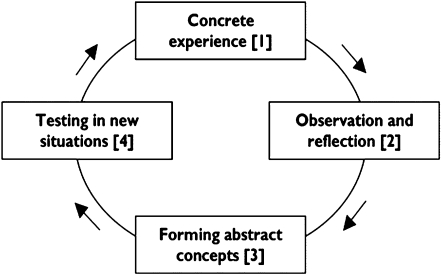

A portfolio may be defined as a purposeful collection of evidence that represents a student's learning, progress, and achievement, inclusive of an introspective, reflective component.2 The roles of faculty members and students in portfolio evaluation have been defined as follows: faculty members identify desired competencies, standards, and guidelines for evaluation, including a definition of what artifacts constitute suitable evidence of achievement of the desired ability-based outcome; students select and provide rationale for inclusion of artifacts as evidence of their accomplishment of learning progression and meeting the desired competency.3 The reflective component of the student portfolio provides opportunity for critical analyses of portfolio contents, an essential step in completion of the experiential learning cycle, as depicted by Kolb (Figure 1).4

Figure 1.

Kolb's Experiential Learning Cycle.4

The paucity of data characterizing the use of student portfolios in experiential learning in the pharmacy literature is what prompted this evaluation. The curricular goals were to demonstrate achievement of 3 desired ability-based outcomes by reviewing student-selected components of electronic portfolios in an APPE, and to assess a fourth ability-based outcome by rubric analysis of student self-reflective essays.

DESIGN

During 2006 and 2007, doctor of pharmacy students in their final year APPE were instructed by the director of experiential education to produce portfolios which would be electronically submitted as e-mail attachments to the director; electronic transmittal was instituted as a convenient alternative to printing, mailing, or faxing documentation of materials, as many students were assigned to sites distant from the college campus, and electronic files could be reviewed and stored efficiently. Students were directed to select work products from any APPE to demonstrate achievement of specified, desired ability-based outcomes published in the APPE course manual, as predicated on the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education outcomes, and evaluated during experiential assessments, as detailed in the following excerpt from the APPE course manual: 5

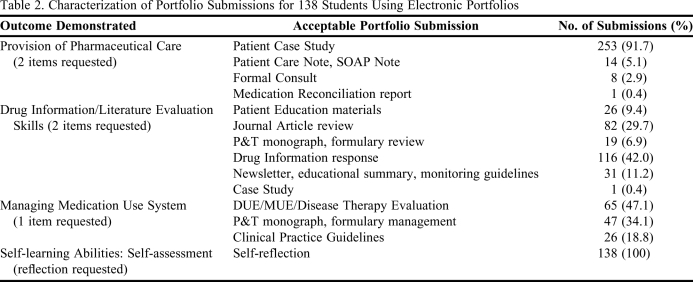

(1) Outcome: Provide pharmaceutical care (2 items requested): acceptable examples include case presentation write-ups; patient care plans; pharmacy consult recommendations, etc. Students may select other applicable items that would meet the stated outcome.

(2) Outcome: Drug information/literature evaluation skills: provide pharmaceutical information to health professionals and the general public (2 items requested): acceptable examples include formal drug information responses; patient education brochures; pharmacy newsletter publications; drug monograph for Pharmacy & Therapeutics (P & T) committee; journal club article reviews; etc. Students may select other applicable items that would meet the stated outcome.

(3) Outcome: Managing the medication use system: conducting drug use evaluation (DUE); participating in formulary management (1 item requested): acceptable examples include DUE project report, clinical practice guidelines, disease state management protocol, P&T monograph, etc. Students may select other applicable items that would meet the stated outcome. Please do not send PowerPoint slide presentation as evidence of meeting this outcome.

(4) Outcome: Self-learning abilities and habits: student shall effectively self-assess (1 item requested): a reflection paper (not to exceed 600 words) on how the APPEs that you participated in shaped you as a pharmacist; more specifically, how will you use these experiences to your benefit in your future role as pharmacist; and how has the APPE program developed you into a pharmacist? Please also include a brief statement of your plan for continued improvement (life-long learning, etc.), as you walk out the door of the college. Feel free to reference certain rotations/experiences/projects in your reflection.

This evaluation was submitted to the college's investigative review board and received exempt status.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

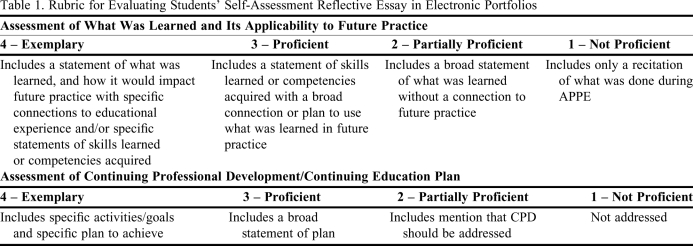

The planned assessment of the first 3 competencies included a review of the submitted item by the director of experiential education to determine whether the submission demonstrated the desired ability-based outcome. If the item did not, students were notified that an alternative work product should be submitted. Once the item was deemed acceptable and the portfolio was complete, data were compiled and characterized. The fourth competency (assessment of self-learning/reflection) was evaluated independently by the 2 authors, using a rubric developed by the authors with the assistance of an instructional technologist to determine how well students met the self-learning competency (Table 1). In cases where the 2 evaluators differed in rankings, a mean rank score between the 2 assessors was recorded.

Table 1.

Rubric for Evaluating Students' Self-Assessment Reflective Essay in Electronic Portfolios

Abbreviations: CPD = continuing professional development; APPE = advanced pharmacy practice experiences.

Students were reminded to properly de-identify all patient-specific items submitted. They were given a late April 2007 deadline for submission so that a work product from their last scheduled APPE could be submitted. Completion of the portfolio was a prerequisite for graduation.

Electronic portfolios were available for evaluation by 138 of 141 students in the 2007 class; the remaining 3 students submitted portfolios that were either electronically lost or could not be accessed. Table 2 characterizes the work products that students elected to submit to demonstrate achievement of the stated ability-based outcome to complete the portfolio assignment. All student portfolios contained work products that demonstrated achievement of the 3 desired ability-based outcomes. While the number of times the director of experiential education rejected an item and requested an alternative item for portfolio submission was not tabulated, the most common reason for notifying the student was because of a portfolio omission.

Table 2.

Characterization of Portfolio Submissions for 138 Students Using Electronic Portfolios

Abbreviations: SOAP = subjective, objective, assessment plan; P&T = pharmacy & therapeutics committee; UE/MUE = drug usage evaluation/medication usage evaluation.

One hundred thirty-eight reflective essays were submitted, and 135 were available to be assessed (3 were lost electronically). Each author/evaluator (director of experiential education and director of continuing professional development) independently reviewed the essays and ranked the 2 domains using the rubric (domain 1: assessment of what was learned/applicability to future practice; and domain 2: assessment of continuous professional development/continuing education plan). The 2 evaluators' rankings concurred on 78 students and differed on 57. For domains 1 and 2, the average rank of how well students met the outcome was 2.9 and 2.3, respectively, on a scale ranging from 1 to 4.

DISCUSSION

Reflective portfolios can provide evidence of professional development and achievement of desired competencies.6 Our approach was a hybrid of showcasing best work that demonstrated achievement of a desired competency or ability-based outcome, evidenced by uploading work products that met the pharmaceutical care provision, drug literature evaluation, and management of the medication use system outcomes; and introspection, demonstrated by the self-reflective essay that students composed to illustrate what was learned and the applicability of APPEs to future practice, and plans for continuing professional development. Students were ultimately responsible for selecting pertinent work product artifacts for the portfolio, and generally would select examples of what they considered their best work; however, each selected artifact had to sufficiently demonstrate achievement of the desired ability-based outcome, or it was not considered suitable for portfolio inclusion by the experiential education director. Each artifact submitted was a bona fide work product prepared on an APPE, and assessed sometimes formatively and always summatively by the APPE preceptor. For example, students might be required to submit a formal case presentation write-up for evaluation by the preceptor and for credit on an ambulatory care APPE; this write-up could serve also as an artifact for inclusion in the portfolio, meeting one of the desired ability-based outcomes (providing pharmaceutical care). In this model, the experiential education division depended upon the precepting faculty members to assess the content of the work products, which ultimately would appear in the portfolio as evidence of achievement of a desired ability-based outcome. This proved to be a successful model to demonstrate mastery, coupling the expertise of the precepting faculty members (in reviewing each assignment for content accuracy, etc) and experiential education staff members to determine which artifacts suitably reflected achievement of desired APPE outcomes.

The students' self-assessment essay composed the reflective component of the portfolio. Poirier and colleagues have studied students' value of the reflective portfolio and reported the following student observations: “When time is taken for reflection, things acquire more value and importance”; “Sometimes looking back can help you in moving forward”; and “I learned the value of maintaining a portfolio as a learning tool and as a measurement of progress in achieving professional goals.”7 Our experience with the reflective essay provided evidence that through the culminating APPE curricular experience, students really do comprehend that the didactic curricular components served as a building block as the students put the pieces of the puzzle together in the experiential setting. Numerous students commented in their reflective essays that a commitment to lifelong learning is essential; that interpersonal communications with health care providers and patients are integral components of pharmacy practice; and that applying clinical judgment to each patient is critical for successful pharmaceutical care. We routinely have publicized excerpts from student reflective portfolio essays to preceptors so that they too would be aware of the collective impact they were making in the education of pharmacy students.

During 2007-2008, the portfolio process was continued for 193 students using Blackboard (Blackboard Inc., Washington, DC) as the repository for portfolio development. For 2008-2010, the process was converted to a commercially available electronic portfolio system, Pharmacy Educational Management System (PEMS, E*value Healthcare Education Solutions, Minneapolis, MN), which allowed the number of collected artifacts to be expanded to include a specified number of assignments per specified type of APPE (eg, community, institutional, etc). An added benefit of the commercial system is that preceptors can view students' portfolios.

SUMMARY

Implementing an electronic student portfolio with a reflective component successfully demonstrated achievement of desired ability-based outcomes through an APPE program. Our experience with the reflective essay provided evidence that the APPE served as a culminating curricular experience in which students demonstrated positive attributes of pharmacy practice learned in the experiential setting, recognizing the importance of lifelong learning. This model can be transferred easily to other institutions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Andreas Karatsolis, PhD, in the creation of the Rubric for Evaluation of Student APPE self-assessment reflection paper.

REFERENCES

- 1. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Inc. http://www.ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2010.

- 2.McMullan M, Endacott R, Gray MA, et al. Portfolios and assessment of competence: a review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(3):283–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers DW, Glassman P. A primer on competency-based evaluation. J Dent Educ. 1997;61(8):651–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolb DA. Experiential Learning. Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 5. 2004Education Outcome, Centers for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education, American Association of College of Pharmacy, Alexandria, VA. http://aacp.org/Docs/MainNavigation/resources/6075_CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed April, 21, 2010.

- 6.Plaza CM, Draugalis JR, Slack MK, Skrepnek GH, Sauer KA. Use of reflective portfolios in health sciences education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2) doi: 10.5688/aj710234. Article 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poirier TI, Santanello CR, Gupchup GV. A student orientation program to build a community of learners. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1) doi: 10.5688/aj710113. Article 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]