Abstract

In the present investigation, the authors explored potential predictors of White students’ general emotional responses after they reflected on their Whiteness in a semi-structured interview (n = 88) or written reflection (n = 187). Specifically, the authors examined how color-blindness (i.e., awareness of White privilege) and racial affect (i.e., White empathy, White guilt, and White fear), assessed before the interview or written reflection, may predict positive and negative emotional responses, assessed immediately following the interview or written reflection. Furthermore, the authors considered whether affective costs of racism to Whites moderated the association between racial color-blindness and general positive and negative emotional responses of White students. Findings indicated that affective costs of racism moderated associations between racial color-blindness and general emotional responses. Specifically, White fear moderated associations for the written reflection group whereas White empathy moderated an association in the interview. White guilt did not moderate, but instead directly predicted a negative emotional response in the written reflection group. Findings suggest that the interaction between racial color-blindness and racial affect is important when predicting students’ emotional responses to reflecting on their Whiteness. Implications for educators and administrators are discussed.

As many colleges and universities seek to extend racial diversity education, create inclusive campuses, and prepare students to be active participants in a multicultural democracy and pluralistic global economy, a critical element of this mission is to educate White students about their dominant status in society (Adams, Bell, & Griffin, 2007; Bohmer & Briggs, 1991; Johnson, 2006; Lawrence & Bunche, 1996; Marshall, 2002; Tatum, 1992). To facilitate this racial self-exploration among White students, educators encourage them to contemplate, write about, and discuss their Whiteness as they learn about pervasive societal inequities. Although university instruction often is conceptualized in terms of fostering content knowledge (i.e., intellectual understanding of a particular subject matter), topics that deal with racial issues in U.S. society are emotionally charged. Therefore, when teaching about race and racism, educators also must attend to students’ emotional responses to the substantive material (Hogan & Mallott, 2005; Lucal, 1996; Trainor, 2005). Little is known, however, about the factors that predict the general emotional responses of White students as they reflect on racism and White privilege.

Scholars and educators in psychology, education, and sociology emphasize the particular importance of White students’ emotional responses to learning about race, racism, and White privilege (Bonilla-Silva, 2003; Carter, 2003; Goodman, 2001; Lawrence, 1996; Leach, Snider, & Iyer, 2002; Levine-Rasky, 2000; Tatum, 1992). Furthermore, some argue that the primary task of instructors of such courses is to help students move from a detached, intellectual understanding of course content, to a more personal affective understanding (Daly, 2005; Reason, Scales, & Roosa Millar, 2005). When describing his racial-cultural counseling laboratory course for example, Carter (2003) explained that it is essential for White students to examine their affective experiences in conjunction with their intellectual understanding if they are to develop cultural competence as counselors. Similarly, when teaching White women about racism and privilege, Gillespie, Ashbaugh, and DeFieore (2002) asserted that intensive emotional work in the classroom is necessary alongside dissemination of subject matter. Positive emotions such as interest, excitement, and enthusiasm, might facilitate White students’ engagement with course content, examination of their own White racial identity, and commitment to becoming racial allies (Daly, 2005; Reason et al., 2005). Negative emotional responses, such as feeling distressed, upset, or ashamed, may either disrupt the learning process (Reason et al., 2005) or motivate social justice action (Kernahan & Davis, 2007). An extremely distressed response may result in White students’ defensiveness or resistance to diversity education altogether (Reason et al., 2005). Consequently, research is needed to understand how both cognitive and affective components operate in the educational context when White students reflect on race-related issues. To date, little empirical research exists that examines these components concomitantly.

Racial Color-Blindness and Diversity Education

Racial color-blindness refers to the denial, distortion, and minimization of race and racism in the U.S. (Bonilla-Silva, 2003; Thompson & Neville, 1999). Scholars have conceptualized racial color-blindness as a set of attitudes, or ideology, that reflects unawareness of various forms of racism (e.g., institutional and blatant) and White privilege (Bell, 2003; Neville, Lilly, Duran, Lee, & Browne, 2000). Previous research among White students indicates that greater racial color-blindness is associated with higher levels of modern racism and belief in a just world (Neville et al., 2000), negative attitudes toward affirmative action (Awad, Cokely, & Ravitch, 2005), and greater irrational fear of racial minorities (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004). Moreover, higher racial color-blindness also has been associated with lower levels of openness to diversity, less engagement in diversity courses and campus-sponsored diversity activities (Spanierman, Neville, Liao, Hammer, & Wang, 2008), and more positive perceptions of campus climate than those with lower color-blind racial attitudes (Worthington, Navarro, Loewy, & Hart, 2008). Taken together, these findings attest to the importance of addressing students’ racial color-blindness and thus increasing students’ awareness of racism and White privilege as critical elements of diversity education. Moreover, one form of racial color-blindness that is particularly relevant for White university students is unawareness of White privilege, as diversity education has a strong emphasis on educating White students about White privilege (Adams et al., 2007; Johnson, 2006). Thus, additional research is warranted that examines how White students respond to White privilege education.

Notably, scholars and educators have observed that challenging White students’ color-blind racial attitudes may result in strong emotional responses that could differentially influence the learning process (Goodman, 2001). For example, White students who are unaware of White privilege may feel angry or distressed when learning about racial privilege, whereas those who are aware of White privilege may experience White guilt or moral outrage when they examine these issues in the classroom (Iyer, Leach, & Pedersen, 2004; Lawrence & Bunche, 1996; Leach et al., 2002). However, there is a dearth of empirical research that examines how awareness of White privilege may predict White students’ general emotional responses to reflecting on racism and their Whiteness. Understanding the link between awareness of White privilege and students’ emotional responses has the potential to inform pedagogy related to the diversity education of White students.

Costs of Racism to White Students and Diversity Education

In addition to color-blind racial attitudes, other scholarship suggests that race-related affect (i.e., affective responses specific to one’s racial group membership) also is important to consider as White students explore racism and White privilege (Dovidio, Esses, Beach, & Gaertner, 2003; Goodman, 2001; Tatum, 1992). One promising framework for understanding race-related affect is the psychosocial costs of racism to Whites (see Goodman, 2001; Kivel, 2002; Spanierman & Heppner, 2004; Spanierman, Oh et al., 2008, Spanierman & Soble, 2009). In particular, as delineated by Spanierman and Heppner (2004), affective costs of racism to Whites include White guilt, White empathy (i.e., feelings of sadness and anger about the existence of societal racism), and irrational White fear of racial minorities. These dimensions of racial affect have been shown to relate to a variety of relevant constructs among White university students. For example, higher levels of White empathy and White guilt have been associated with higher levels of multicultural education, racial awareness, and cultural sensitivity (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004; Spanierman, Poteat, Wang, & Oh, 2008). Conversely, White fear has been linked to lower levels of multicultural education, racial awareness, cultural sensitivity, and interracial friendships (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004); and less support for affirmative action and higher levels of racial prejudice (Case, 2007). These associations strongly suggest that affective costs of racism are critical factors related to the diversity education of White students.

Costs of Racism to Whites as a Moderator for Awareness of Privilege and General Emotion

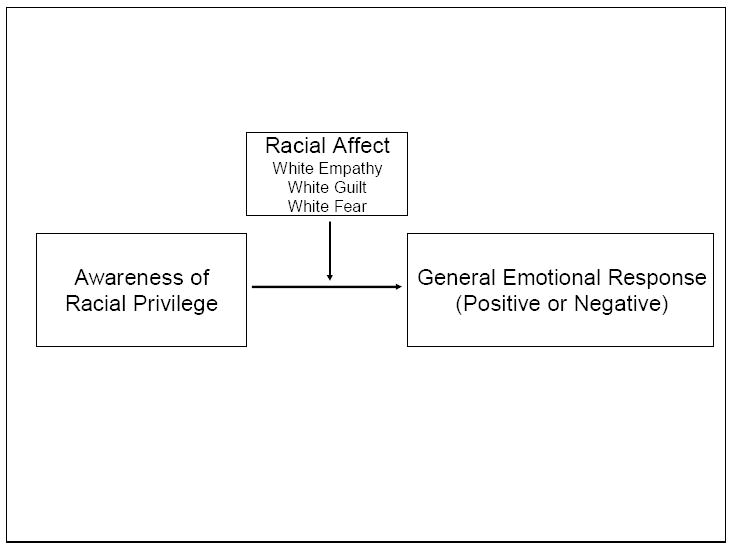

As noted above, previous research has called for the concurrent examination of cognitive and affective dimensions of student racial attitudes. Moreover, some scholars (e.g., Engberg, 2004) have underscored the differential effects of various educational interventions on students’ racial attitudes and thus argued for research methods that capture psychological processes that underlie student change. One method by which to examine underlying psychological processes is testing interaction effects of moderating variables. A moderating variable “addresses ‘when’ or ‘for whom’ a predictor is more strongly related to an outcome,” in contrast to a mediating variable that “establishes ‘how’ or ‘why’ one variable predicts or causes an outcome variable” (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004, p. 116). Therefore, testing moderating effects of racial affect can reveal how associations between an independent variable (e.g., White privilege awareness) and dependent variable (e.g., feeling upset) may be stronger or weaker in different sub-groups (e.g., students high or low in White empathy). Understanding how racial affect interacts with awareness of White privilege has the potential to inform diversity pedagogy for specific subgroups of White students. However, there has not been a systematic examination of multiple dimensions of racial affect (i.e., White guilt, White fear, White empathy) as possible moderators of the association between awareness of racial privilege and general emotional responses, as depicted in our conceptual model in Figure 1. Therefore, to clarify and extend this literature, in the current study we test whether racial affect moderates associations between color-blind racial attitudes and general positive and negative emotional responses when White students reflect on Whiteness and societal racism.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model: Racial Affect Moderating Awareness of Privilege and Emotional Response.

Conceptual model of racial affect moderating the association between Awareness of Racial Privilege and a positive or negative general emotional response.

Present Study

Scholars have called for examination of both cognitive racial attitudes and emotional responses of White students, with the proposition that further understanding may lead to more effective classroom strategies and interventions (Carter, 2003; Reason et al., 2005; Tatum, 1992). Because diversity educators have proposed various strategies for working with both positive and negative emotional responses in the classroom, such as journal writing (Carter, 2003: Mio & Barker-Hackett, 2003) and dialoguing with others about racial issues (Lawrence, 1996; Locke & Kiselica, 1999), we examined both of these contexts in the present study. Moreover, because scholars have argued for examination of underlying processes by which educational interventions influence student change, we incorporate racial affect as a potential moderator in the present investigation. Specifically, we examine whether racial affect (i.e., affective costs of racism to Whites) moderated associations between one dimension of racial color-blindness (i.e., awareness of White privilege) and general positive and negative emotional responses among White students reflecting on societal racism and White privilege. We tested potential effects in two contexts used in diversity education: an interpersonal discussion via a face-to-face interview, and an independent written reflection. This design allowed us to examine how awareness of racial privilege and racial affect, assessed before the interview or written reflection, may predict general emotional responses, assessed immediately following the interview or written reflection. Moreover, we examined whether racial affect moderated associations between awareness of racial privilege and general emotional responses.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 275 undergraduate students from a large Midwestern university introduction to psychology course who participated for course credit. This was a land-grant university with a predominately in-state (88.5%) and White student body (67.5% White, 12.6% Asian American, 6.5% African American, 6.3% Latina/o, 4% international, .3% Native American, and the remainder unknown). These demographic data reflect the undergraduate student population during data collection in fall 2005. Only self-identified White students received notification to participate through an online subject-pool system. Participants were blind to the purpose and content of the study and did not know whether they would be interviewed or given a written reflection previous to arriving for participation. Upon arrival, 88 participants were interviewed (i.e., Interview group). For the Interview group, males and females were represented equally (44 each), and their average age was 18.88 (SD = 1.09). The other 187 participants completed a written reflection, rather than a face-to-face interview, which focused on their race and societal racism (i.e., Written Reflection group). Of these 187 participants, 61.5% were male with an average age of 18.76 (SD = 0.92).

Measures

Racial color-blindness

We used the Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale of the Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale-Short Form (CoBRAS-SF; Neville, Low, Liao, Walters, & Landrum-Brown, 2007) to assess students’ unawareness of White privilege in U.S. society. The 14-item CoBRAS-SF is an abbreviated version of the original 20-item CoBRAS (Neville et al., 2000). A sample item from the 6-item Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale includes “Everyone who works hard, no matter what race they are has an equal chance to become rich.” Items are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) with higher scores representing higher levels of a particular aspect of racial color-blindness. To facilitate understanding in the present study, we reversed scored the items so that higher sub-scales scores indicated greater awareness of privilege. The internal consistency of the longer version has been well documented among White students (e. g., α = .84 - .91; Neville et al., 2000), and reliability estimates for the short version have been found to be similar (Neville et al., 2007). For the present investigation, the internal consistency estimate of the Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale was α = .73. Further evidence for the validity of the scale has been shown in subsequent research (e.g., Spanierman, Neville, Liao, Hammer, & Wang, 2008).

Affective costs of racism to Whites

We used the Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites Scale (PCRW; Spanierman & Heppner, 2004) to assess participants’ affective costs of societal racism. The 16-item self-report measure uses a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores reflect higher experiences of costs. The measure includes three subscales: (a) White Empathic Reactions Toward Racism, focusing on sadness and anger about the existence of racism (6 items, “I am angry that racism exists”), (b) White Guilt (5 items, “Sometimes I feel guilty about being White”), and (c) White Fear of People of Color (5 items, “I am distrustful of people of other races”). Among White university students, internal consistency estimates for each of the subscales have ranged as follows: White Empathy α = .70 to .85, White Guilt α = .73 to .81, and White Fear α = .63 to .78 (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004; Spanierman, Todd, & Anderson, 2009). In the current investigation, coefficient alphas for the three PCRW subscales were .80 (White Empathy), .77 (White Guilt), and .71 (White Fear). Additional evidence for the validity of this scale has been shown among employed adults (Poteat & Spanierman, 2008) and through other research with college students (e.g., Spanierman, Poteat, Beer, & Armstrong, 2006; Spanierman, Todd, & Anderson, 2009). Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between the psychosocial costs of racism to Whites and awareness of racial privilege are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations of Study Variables

| Written Reflection | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD | Min | Max | |

| 1. White Guilt | — | .24* | -.01 | .44* | 2.09 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 5.20 | |

| 2. White Empathy | .25* | — | -.26* | .27* | 4.50 | 0.84 | 1.50 | 6.00 | |

| 3. White Fear | -.10 | -.42* | — | -.09 | 2.78 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 5.20 | |

| 4. Awareness of Racial Privilege | .20 | .22* | -.13 | — | 3.50 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 6.00 | |

| Interview Group Mean | 2.20 | 4.62 | 2.78 | 3.58 | 2.05 | ||||

| Interview Group SD | 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 0.63 | ||||

| Interview Group Minimum | 1.00 | 2.83 | 1.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | ||||

| Interview Group Maximum | 4.20 | 6.00 | 4.80 | 5.50 | 3.67 | ||||

Note. Intercorrelations for the Written Reflection group (n = 187) are presented above the diagonal, and intercorrelations for the Interview Group (n = 88) are below the diagonal. Means and stand deviations for the Written Reflection group are presented in the vertical columns, and means and standard deviations for the Interview group are presented in the horizontal rows.

p < .05.

General positive and negative emotional responses

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) was used to assess participants’ emotional responses at the beginning and end of study participation. Watson et al. described positive and negative affect as orthogonal types of mood or emotional reactivity, and for this study we used the scales as measures of mood state, or general emotional response. Participants rate 10 positive (i.e., interested, excited, strong, enthusiastic, proud, alert, inspired, determined, attentive, and active) and 10 negative (i.e., distressed, upset, guilty, scared, hostile, irritable, ashamed, nervous, jittery, and afraid) affect words based on, “the extent you feel this way right now, not how you generally feel.” The scale anchors are 1 (very slightly or not at all), 2 (a little), 3 (moderately), 4 (quite a bit), or 5 (extremely). Scores for positive and negative emotional response are formed by averaging the respective positive and negative emotion ratings. Internal consistency estimates at Time 1 and Time 2 were computed for both negative (Time 1, α = .84, Time 2, α = .86) and positive (Time 1, α = .85, Time 2, α = .88) affect scales, which were similar to reliabilities reported in previous research (α = .89 and α = .85, for positive and negative respectively; Watson et al., 1988). Furthermore, the positive and negative affect scales were orthogonal, as in previous research (Watson et al., 1988).

Interview and written reflection prompts

The semi-structured interviews consisted of open-ended questions that were developed from a thorough review of the Whiteness literature. Interview questions focused on racial self-awareness, emotional responses related to being White, level of comfort in interacting with people of color, personal stereotypes, and White privilege. The written reflection consisted of 34 short statements following the content of the interview. After each statement, participants were asked to “explain why you agree/disagree and give some examples.” Thirty of the written reflection items were parallel to the interview questions, and four additional statements asked about openness to learning from people of color. Finally, we included a short essay on social inequality as the final task of the written reflection to highlight dominant group status. For purposes of this study, the interview and written reflection prompts served as stimuli to provoke emotional responses; therefore, the qualitative data are not analyzed in the present investigation. A list of the interview and written reflection prompts is available upon request from the first author.

Procedures

Unknown to the participants, they were assigned to the interview or written response group depending on which study slot they chose through the online subject-pool system. After obtaining informed consent, participants completed the short form of the PANAS (Time 1) and a counter-balanced packet of surveys, which included the PCRW, CoBRAS-SF, and additional measures that were not used in this study. After completing the surveys, one set of participants was interviewed (n = 88), whereas the other set was given the written reflection items (n = 187). After completing the interview or written reflection, both sets of participants again completed the PANAS (Time 2) to assess their general emotional responses. This design was selected in order to examine how the study variables predicted positive and negative emotional responses, controlling for initial positive and negative emotions.

For the interview, a trained interviewer conducted a semi-structured one-on-one interview, which lasted on average 34 minutes (SD = 6.4, Range = 20-47). The first author, a White man, conducted 31 of the interviews. Two White undergraduate women conducted 18 and 19 interviews respectively with the remaining 20 conducted by a White male undergraduate. There were no significant differences in positive or negative emotional responses at Time 2 between participants interviewed by a male or female interviewer. In addition to having interview training as part of previous coursework, all undergraduate interviewers were trained to conduct the current interview protocol and to ask appropriate follow-up questions when needed. The written reflection data were collected by the first author, a White man, in a group setting with 20-35 White students arriving simultaneously to participate.

Results

Analytic Strategy

We computed the partial correlations to examine if awareness of racial privilege or each affective cost of racism (i.e., White empathy, White guilt, and White fear) predicted general emotional responses (i.e., PANAS scores) at Time 2 after controlling for Time 1 PANAS scores. Next, we followed the process outlined by Frazier et al. (2004) to test whether racial affect moderated the association between awareness of racial privilege and general emotional responses. We tested the interactions between each affective cost of racism with awareness of racial privilege in predicting positive or negative emotional response. We conducted these tests separately for each situation (i.e., interview or written reflection). As recommended by Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003) and Frazier et al., (2004), we standardized all predictor variables and covariates. To examine model assumptions, we constructed residual plots and found the data to satisfy the necessary assumptions. For significant interactions we used a median split to group individuals into “low” or “high” costs of racism groups (e.g., high versus low White fear) and subsequently examined the association between awareness of racial privilege and general emotional responses within each of these groups. Also recommended by Frazier et al. (2004), we formed interaction terms with the covariate and all other model variables to determine whether these interactions significantly increased the R2, which would indicate the need for further testing to understand the impact of the covariate; however, none of these interactions were significant. Finally, if awareness of racial privilege or costs of racism variables had significant partial correlations, we entered them into the regression equation in a third step to examine if they predicted emotional response in addition to the moderation. The significant results are presented below and in Table 2, with non-significant results excluded for brevity.

Table 2.

Moderation and Mediation for Written Reflection (N = 187) and Interview (N = 88) Groups

| Step and Variable | β | SE β | 95% CI | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Written Reflection Group | ||||

| Negative Emotional Response Time 2 | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Negative Emotional Response Time1 | 0.86** | 0.06 | [0.74, 0.97] | |

| Awareness of Racial Privilege | 0.03 | 0.03 | [-0.03, 0.04] | |

| White Fear | 0.03 | 0.03 | [-0.04, 0.10] | .54** |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Awareness of Racial Privilege * White Fear | -0.06* | 0.03 | [-0.12, -0.003] | .01* |

| Step 3 | ||||

| White Guilt | 0.10* | 0.04 | [0.03, 0.17] | |

| White Empathy | 0.06† | 0.03 | [-0.004, 0.13] | .03* |

| Positive Emotional Response Time 2 | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Positive Emotional Response Time1 | 0.79** | 0.06 | [0.67, 0.92] | |

| Awareness of Racial Privilege | 0.06 | 0.04 | [-0.02, 0.14] | |

| White Fear | -0.001 | 0.04 | [-0.09, 0.09] | .48** |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Awareness of Racial Privilege * White Fear | -0.07* | 0.04 | [-.15, -0.0005] | .01* |

| Interview Group | ||||

| Negative Emotional Response Time 2 | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Negative Emotional Response Time 1 | 0.58** | 0.14 | [0.29, 0.86] | |

| Awareness of Racial Privilege | -0.02 | 0.05 | [-0.12, 0.09] | |

| White Empathy | -0.08 | 0.06 | [-0.20, 0.03] | .21* |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Awareness of Racial Privilege * White Empathy | 0.14* | 0.07 | [0.01, 0.27] | .05* |

| Positive Emotional Response Time 2 | ||||

| Step 1 | ||||

| Positive Emotional Response Time1 | 0.77** | 0.09 | [0.59, 0.95] | |

| White Empathy | 0.14* | 0.06 | [0.02, 0.27] | .47* |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10.

Interview Group

Negative emotional response

First, none of the partial correlations for awareness of racial privilege or costs of racism were significant, indicating that none of these variables independently predicted negative emotional response at Time 2 after controlling for negative emotional response at Time 1. Second, we tested if each of the costs of racism variables moderated the association between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response at Time 2. The only significant interaction was for White empathy and awareness of racial privilege (p = .03), indicating that White empathy moderated the association between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response. To understand the nature of this moderation, we tested the association between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response in “low” and “high” White empathy groups separately. We found a significant association (β = -0.21, SE = 0.10, p = .04) between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response at Time 2 in the “low” White empathy group, but no significant association in the “high” White empathy group (p = .18). As displayed in Figure 2, this indicates that for those low in White empathy, greater awareness of racial privilege related to a lower negative emotional response (i.e., less distress), whereas no association was present for those high in White empathy

Figure 2. Predicting Negative Emotional Responses in the Interview Situation.

Plot of significant White Empathy X Awareness of Privilege interaction at the mean level of covariate Negative Emotion Time 1.

Positive emotional response

The partial correlations indicated that White empathy (r = .24, p = .03) was the only significant predictor of positive emotional response at Time 2 after controlling for positive emotional response at Time 1. This indicates that higher White empathy was associated with a more positive response (e.g., excited, enthused). None of the affective costs of racism moderated the association between awareness of racial privilege and a positive emotional response.

Written Reflection Group

Negative emotional response

First, the partial correlations indicated that both White empathy (r = .16, p = .03) and White guilt (r = .23, p = .002) were significant predictors of negative emotional response at Time 2 after controlling for Negative Emotions at Time 1; no other variables were significant predictors. Second, we tested if each affective cost of racism variable moderated the association between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response at Time 2. We found a significant interaction between White fear and awareness of privilege (p = .04), indicating that White fear moderated associations between awareness of privilege and negative emotional response. To understand the nature of this moderation, we tested the relation between awareness of privilege and negative emotional response in “low” and “high” White fear groups separately. We found a significant positive association (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = .02) between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response in the “low” White fear group, and no significant association (p = .41) in the “high” White fear group. As displayed in Figure 3, this indicates that for those low in fear and mistrust of people of color, greater awareness of racial privilege related to greater negative emotional response (e.g., distress and upset).

Figure 3. Predicting Negative Emotional Responses in the Written Reflection Situation.

Plot of significant White Fear X Awareness of Privilege interaction at the mean level of the covariate Negative Emotion Time 1.

Finally, based on the significant partial correlations, we entered both White guilt and White empathy into the prediction equation, and found White guilt to be a significant predictor of negative emotion in the model (β = 0.10, SE = 0.04, p = .01), whereas White empathy was not significant in this model. In sum, findings indicated that higher White guilt predicted a greater negative emotional response following the written reflection, and White fear moderated the association between awareness of racial privilege and negative emotional response.

Positive emotional response

None of the partial correlations for study variables were significant predictors of positive emotional response at Time 2 after controlling for positive emotional response at Time 1. We then tested each of the costs of racism variables to examine potential moderating effects on the association between awareness of racial privilege and a positive emotional response. The only significant interaction was for White fear and awareness of privilege (p = .049). To understand the nature of the moderation, we examined the association between awareness of privilege and positive emotional response in “low” and “high” White fear groups separately. We found a significant positive association (β = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = .04) between awareness of racial privilege and positive emotional response in the “low” White fear group, and no significant association (p = .79) in the “high” White fear group. As displayed in Figure 4, this indicates that for those low in fear and mistrust of people of color, greater awareness of racial privilege related to a more positive emotional response. In sum, White fear moderated associations between awareness of racial privilege and a positive emotional response.

Figure 4. Predicting Positive Emotional Responses in the Written Reflection Situation.

Plot of significant White Fear X Awareness of Privilege interaction at the mean level of the covariate Positive Emotion Time 1.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine potential predictors of White students’ general emotional responses after they reflected on societal racism and Whiteness. As noted by numerous diversity scholars (e.g., Goodman, 2001; Tatum 1992), understanding the racial attitudes, affective costs of racism to Whites, and situations that are associated with negative and positive emotional responses has the potential to inform racial diversity education pedagogy for White students. Moreover, we proposed that affective costs of racism to Whites (i.e., racial affect) would moderate associations between awareness of racial privilege and general emotional responses, and tested this across two contexts common to diversity education (i.e., written reflection and face-to-face interviews). We found that White fear moderated associations in the written reflection situation whereas White empathy moderated an association in the interview situation.

White Fear as a Moderator in the Written Reflection Group

We learned that irrational fear of racial minorities moderated associations between awareness of White privilege and negative and positive emotions for students in the written reflection situation, but not the interview context. This indicates that among White students who score low on White fear, and thus feel more trusting of people of color, greater awareness of White privilege was associated with greater positive and negative emotional responses. For those high in White fear (i.e., less trusting of people of color) there was no association between color-blind racial attitudes and general emotional responses. One interpretation of this moderation is that participants experienced greater emotional reactions (i.e., positive or negative) to the written reflection when they were more trusting of people of color. Given that lower levels of White fear have been associated with more interracial friendships (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004), it is possible that when students have low White fear, they have greater personal connections with people of color. Therefore, participants low in White fear may have connected their awareness of racial privilege to implications for their friends of color, resulting in stronger emotional reactions than those participants who did not trust people of color. This link between interpersonal friendships adds to the already vast literature examining how contact and interracial friendship may help to reduce prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). Finally, because White fear emerged as a moderator only in the written reflection situation, it is possible that interracial trust provides a foundation for participants to engage emotionally with racial issues privately, rather than in front of a White interviewer. Diversity educators should be attuned to students’ levels of White fear, and may recognize that independent reflection assignments may lead to more emotional engagement for some White students but not others.

The White fear moderation in Figure 3 also showed an elevated negative emotional response after the written reflection for two types of White students: those who were high in awareness and low in fear in contrast to those who were low in awareness and high in fear. The meaning of this distressed response may be different for these two groups, with implications for how diversity educators address a distressed response. If a student is low in awareness and high in fear, they may have a distressed response at the beginning of a diversity course stemming from defensiveness toward the material; however, if a student is aware of privilege and is also trusting of people of color, their distress may reflect engagement with the material. Diversity educators may need to deal with these two types of distress differently, depending on the student’s combination of White fear and awareness of racial privilege. A similar analysis for a positive response after the written reflection (see Figure 4) shows that when students have low awareness, White fear does not seem to matter in predicting a positive response. However, when students have high awareness, it is this high awareness joined with low fear that predicts a positive emotional response. Thus, as students begin to “get privilege” during diversity education, educators may need to then addresses issues related to personal closeness and trust with people of color to encourage White student engagement with the material. In general, high awareness of privilege and low White fear appear to be the ideal combination in predicting a positive and negative emotional response when reflecting on societal racism and racial privilege.

White Empathy as a Moderator in the Interview Group

We found that White empathy moderated an association between awareness of White privilege and a negative emotional response. Specifically, the moderation showed that awareness of racial privilege only predicted a negative emotional response when students were also low in White empathy. Thus, in the present study, students who did not experience anger and sadness about the existence of racism, and at the same time expressed an unawareness of racial privilege, became distressed or upset as a result of the interview on Whiteness. Perhaps, reflection in the context of the interview may have challenged the unaware participants to acknowledge racial privilege, and to stay engaged with uncomfortable material, resulting in elevated distress. This shows the importance of examining both awareness of racial privilege and racial affect when understanding a negative emotional response in an interpersonal situation.

White empathy also directly predicted a positive response in the interview group, with greater empathy associated with a more positive response. This indicates that anger and sadness over racism predicted a positive, engaged emotional response. Therefore, based on these findings, diversity education that seeks to raise students’ awareness of racism and White privilege should aim to increase empathy for those who are targets of racial oppression, as increased empathy may result in a positive, engaged response. Furthermore, there was no association between awareness of racial privilege and a negative emotional response for students high in Empathy. Thus, high empathy may “buffer” associations between awareness of racial privilege and a negative emotional response, further highlighting the importance of increasing empathy as a central goal of racial diversity education.

White Guilt

Although White guilt did not moderate any associations between awareness of racial privilege and general emotional responses, White guilt directly predicted a negative emotional response in the written reflection but not interview group. This finding is not surprising given the literature that views White guilt as an aversive and unpleasant emotion, naturally leading to a distressed and upset response (Iyer et al., 2004). However, it was only in the written reflection group that White guilt predicted a negative emotional response. It is possible that guilt was not predictive among interview participants because these students might have dealt with feelings of guilt differently in a personal, face-to-face context. For example, they might have discussed these guilt feelings or conveyed personal remorse. Furthermore, because an interview prompt invited participants to talk about the ways in which they personally addressed racism, participants in this context might have diminished feelings of guilt as a result of focusing on making amends or restitution, which is consistent with previous research (e.g., Iyer et al., 2004). The current findings add nuance to the role of guilt in predicting a negative emotional response, showing that guilt may not always act as a mediator.

Limitations

Although our findings have utility for diversity pedagogy among White students, they are not without limitations. Because the findings are limited to a Midwestern college population, further research may explore if similar associations are present for students from other geographic regions. Given that the study took place in a laboratory setting, more ecologically valid research needs to be conducted to see if these findings replicate in more naturalistic settings (e.g., a racial diversity classroom). Although we observed emotional responses among participants, we did not isolate which component of study participation (e.g., the surveys, particular content such as White privilege) resulted in emotional response. Future research should be more specific in identifying and isolating the exact components of participation that produce positive and negative emotional responses. Finally, although we used a standard assessment of positive and negative emotional responses (i.e., PANAS), it is difficult to determine the precise meaning of these emotional responses for students. For example, we are not able to differentiate whether positive responses such as “interest,” “excitement,” and “enthusiasm” reflect superficial or authentic engagement. Future research should examine not only general emotional responses, but also what such responses actually mean to the participants.

Implications for Racial Diversity Education Research and Practice

Our results support the call to include both racial attitudes and racial affect in research and practice with White students engaged in diversity education (Reason et al., 2005; Tatum, 1992). Additionally, it is noteworthy that particular types of classroom activities or assignments (i.e., independent writing or intergroup dialogue) may result in different types of emotional responses. Future research should examine how particular aspects of these situations contribute to specific emotional responses (e.g., isolated reflection versus personal contact). Diversity educators may consider the types of positive and negative emotional responses they expect particular activities to evoke, and may ask students to reflect specifically on these emotions as part of the activity to encourage emotional and intellectual engagement with the material (Carter, 2003). Our findings suggest that diversity educators would benefit from training on how to recognize and productively handle White students’ racial affect. Such training could educate about race-specific affect along with general emotional responses of White students while also proposing strategies for how to manage these responses in the classroom (Goodman, 2001). In addition, diversity educators should consider assessing the awareness of racial privilege and racial affect of their students at the beginning and throughout a racial diversity course. This information could be used to tailor the curriculum. For example, if the majority of students score high on White fear of people of color, educators should focus efforts on reducing irrational fear and mistrust in conjunction with other course objectives. Moreover, repeated assessment could provide much needed information. Finally, future research should examine how the general emotional responses of White students influence people of color in a classroom or campus setting. For example, do students of color experience White students’ distress as racial microaggressions in the classroom (Sue et al., 2007, Sue, Lin, Torino, Capodilupo, & Rivera, 2009)? Overall, enhancing racial diversity education for White students by understanding and managing general emotional responses, as well as race-specific affect, has the potential to contribute positively to racial climate in the classroom and on campus (Hurtado et al., 2008; Reid & Radhakrishnan, 2003; Tatum, 1992).

Acknowledgments

This project was completed while the first author was a predoctoral trainee in the Quantitative Methods Program of the Department of Psychology, supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Training Grant PHS 2 T32 MH014257 (awarded to M. Regenwetter). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIMH. We wish to thank Elizabeth Abrams, Helen Neville, and Jacquelyn Beard for their helpful feedback.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/dhe

Contributor Information

Nathan R. Todd, Department of Psychology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Lisa B. Spanierman, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Mark S. Aber, Department of Psychology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

References

- Adams M, Bell LA, Griffin P, editors. Teaching for diversity and social justice. 2. New York: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Awad GH, Cokley K, Ravitch J. Attitudes toward affirmative action: A comparison of color-blind versus modern racist attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2005;35:1384–1399. [Google Scholar]

- Bell LA. Telling tales: What stories can teach us about racism. Race Ethnicity and Education. 2003;6:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bohmer S, Briggs JL. Teaching privileged students about gender, race, and class oppression. Teaching Sociology. 1991;19:154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. New York: Rowman & Littlefield; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT. Becoming racially and culturally competent: The racial-cultural counseling laboratory. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2003;31:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Case KA. Raising White privilege awareness and reducing racial prejudice: Assessing diversity course effectiveness. Teaching of Psychology. 2007;34:231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression / correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Daly B. Taking Whiteness personally: Learning to teach testimonial reading and writing in the college literature classroom. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture. 2005;5:213–246. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Esses VM, Beach KR, Gaertner SL. The role of affect in determining intergroup behavior. In: Mackie DM, Smith ER, editors. From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups. New York: Psychology Press; 2003. pp. 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg ME. Improving intergroup relations in higher education: A critical examination of the influence of educational interventions on racial bias. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74:473–524. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie D, Ashbaugh L, DeFiore J. White women teaching White women about White privilege, race cognizance and social action: Toward a pedagogical pragmatics. Race Ethnicity and Education. 2002;5:237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DJ. Promoting Diversity and Social Justice: Educating People from Privileged Groups. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DE, Mallott M. Changing racial prejudice through diversity education. Journal of College Student Development. 2005;46:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado S, Griffin KA, Arellano L, Cuellar M. Assessing the value of climate assessments: Progress and future directions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 2008;1:204–221. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer A, Leach CW, Pedersen A. Racial wrongs and restitutions: The role of guilt and other group-based emotions. In: Fine M, Weis L, Pruitt LP, Burns Ap, editors. Off White: Readings on power, privilege, and resistance. 2. New York: Routledge; 2004. pp. 345–361. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AG. Privilege, power, and difference. 2. New York: McGraw Hill; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kernahan C, Davis T. Changing perspective: How learning about racism influences student awareness and emotion. Teaching of Psychology. 2007;34:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kivel P. Uprooting Racism: How White People Can Work for Racial Justice. rev. Gabriola Island, British Columbia: New Society Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SM. Bringing White privilege into consciousness. Multicultural Education. 1996;3:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SM, Bunche T. Feeling and dealing: Teaching White students about racial privilege. Teaching & Teacher Education. 1996;12:531–542. [Google Scholar]

- Leach CW, Snider N, Iyer A. “Poisoning the consciences of the fortunate”: The experience of relative advantage and support for social equality. In: Walker I, Smith HJ, editors. Relative deprivation: Specification, development, and integration. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 136–163. [Google Scholar]

- Levine-Rasky C. Framing Whiteness: Working through the tensions in introducing Whiteness to educators. Race, Ethnicity and Education. 2000;3:271–292. [Google Scholar]

- Locke DC, Kiselica MS. Pedagogy of possibilities: Teaching about racism in multicultural counseling courses. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1999;77:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lucal B. Oppression and privilege: Toward a relational conceptualization of race. Teaching Sociology. 1996;24:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall PL. Racial identity and challenges of educating White youths for cultural diversity. Multicultural Perspectives. 2002;4:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh P. White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. In: Rothenberg PS, editor. White Privilege: Essential readings on the other side of Racism. New York: Worth Publishers; 2002. pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mio JS, Barker-Hackett L. Reaction papers and journal writing as techniques for assessing resistance in multicultural courses. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2003;31:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Lilly R, Duran G, Lee R, Browne L. Construction and initial validation of the Color-Blindness Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS) Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Low KSD, Liao H, Walters JM, Landrum-Brown J. Color-blind racial ideology: Testing a context-based legitimizing ideology model. 2007 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Spanierman LB. Further validation of the Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites scale among employed adults. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:871–894. [Google Scholar]

- Reason RD, Scales T, Roosa Millar EA. Encouraging the development of racial justice allies. In: Reason DR, Broido EM, Davis TL, Evans NJ, editors. Developing Social Justice Allies. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass; 2005. pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Reid L, Radhakrishnan P. Race matters: The relation between race and general campus climate. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:263–275. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Heppner MJ. Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites scale (PCRW): Construction and initial validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Neville HA, Liao HY, Hammer JH, Wang YF. Participation in formal and informal campus diversity experiences: Effects on students’ racial democratic beliefs. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 2008;1:108–125. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Oh E, Poteat VP, Hund AR, McClair VL, Beer AM, Clarke AM. White university students’ response to societal racism: A qualitative investigation. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:839–870. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Poteat VP, Beer AM, Armstrong PI. Psychosocial costs of racism to Whites: Exploring patterns through cluster analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:434–441. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Poteat VP, Wang YF, Oh E. Psychosocial costs of racism to White counselors: Predicting various dimensions of multicultural counseling competence. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Soble JR. Understanding Whiteness: Previous approaches and possible directions in the study of White racial attitudes and identity. In: Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of multicultural counseling. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Spanierman LB, Todd NR, Anderson CJ. Psychosocial costs of racism to Whites: Understanding patterns among university students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:239–252. doi: 10.1037/a0015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life. Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62:271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Lin AI, Torino GC, Capodilupo CM, Rivera DP. Racial microaggressions and difficult dialogues on race in the classroom. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:183–190. doi: 10.1037/a0014191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum BD. Talking about race, learning about racism: ‘The application of’ racial identity development theory in the classroom. Harvard Educational Review. 1992;62:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CE, Neville HA. Racism, mental health, and mental health practice. The Counseling Psychologist. 1999;27:155–223. [Google Scholar]

- Trainor JS. “My ancestors didn’t own slaves”: Understanding White talk about race. Research in the Teaching of English. 2005;40:140–167. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]