Abstract

By allowing the regression coefficients to change with certain covariates, the class of varying coefficient models offers a flexible approach to modeling nonlinearity and interactions between covariates. This paper proposes a novel estimation procedure for the varying coefficient models based on local ranks. The new procedure provides a highly efficient and robust alternative to the local linear least squares method, and can be conveniently implemented using existing R software package. Theoretical analysis and numerical simulations both reveal that the gain of the local rank estimator over the local linear least squares estimator, measured by the asymptotic mean squared error or the asymptotic mean integrated squared error, can be substantial. In the normal error case, the asymptotic relative efficiency for estimating both the coefficient functions and the derivative of the coefficient functions is above 96%; even in the worst case scenarios, the asymptotic relative efficiency has a lower bound 88.96% for estimating the coefficient functions, and a lower bound 89.91% for estimating their derivatives. The new estimator may achieve the nonparametric convergence rate even when the local linear least squares method fails due to infinite random error variance. We establish the large sample theory of the proposed procedure by utilizing results from generalized U-statistics, whose kernel function may depend on the sample size. We also extend a resampling approach, which perturbs the objective function repeatedly, to the generalized U-statistics setting; and demonstrate that it can accurately estimate the asymptotic covariance matrix.

Keywords: Asymptotic relative efficiency, Local linear regression, Local rank, Varying coefficient model

1 Introduction

As introduced in Cleveland, Crosse and Shyu (1992) and Hastie and Tibshirani (1993), the varying coefficient model provides a natural and useful extension of the classical linear regression model by allowing the regression coefficients to depend on certain covariates. Due to its flexibility to explore the dynamic features which may exist in the data and its easy interpretation, the varying coefficient model has been widely applied in many scientific areas. It has also experienced rapid developments in both theory and methodology, see Fan and Zhang (2008) for a comprehensive survey. Fan and Zhang (1999) proposed a two-step estimation procedure for the varying coefficient model when the coefficient functions have possibly different degrees of smoothness. Kauermann and Tutz (1999) investigated the use of varying coefficient models for diagnosing the lack-of-fit of regression, regarding the varying coefficient model as an alternative to a parametric null model. Cai, Fan and Li (2000) developed a more efficient estimation procedure for varying coefficient models in the framework of generalized linear models. As special cases of varying coefficient models, time-varying coefficient models are particularly appealing in longitudinal studies, survival analysis and time series data since they allow one to explore the time-varying effect of covariates over the response. Pioneering works on novel applications of time-varying coefficient models to longitudinal data include Brumback and Rice (1998), Hoover, et al. (1998), Wu, et al. (1998) and Fan and Zhang (2000), among others. For more details, readers are referred to Fan and Li (2006) and the references therein. Time-varying coefficient models are also popular in modeling and predicting nonlinear time series data and survival data, see Fan and Zhang (2008) for related literature.

Estimation procedures in the aforementioned papers are built on either local least squares type or local likelihood type methods. Although these estimators remain asymptotically normal for a large class of random error distributions, their efficiency can deteriorate dramatically when the true error distribution deviates from normality. Furthermore, these estimators are very sensitive to outliers. Even a few outlying data points may introduce undesirable artificial features in the estimated functions. These considerations motivate us to develop a novel local rank estimation procedure that is highly efficient, robust and computationally simple. In particular, the proposed local rank regression estimator may achieve the nonparametric convergence rate even when the local linear least squares method fails to consistently estimate the regression coefficient functions due to infinite random error variance, which occurs for instance when the random error has a Cauchy distribution.

The new approach can substantially improve upon the commonly used local linear least squares procedure for a wide class of error distributions. Theoretical analysis reveals that the asymptotic relative efficiency (ARE), measured by the asymptotic mean squared error (or the asymptotic mean integrated squared error), of the local rank regression estimator in comparison with the local linear least squares estimator has an expression that is closely related to that of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank test in comparison with the two-sample t-test. However, different from the two-sample test scenario where the efficiency is completely determined by the asymptotic variance, in the current setting of estimating an infinite-dimensional parameter both bias and variance contribute to the asymptotic efficiency. The value of ARE is often significantly greater than one. For example, the ARE is 167% for estimating the regression coefficient functions when the random error has a t3 distribution, is 240% for exponential random error distribution, and is 493% for lognormal random error distribution.

A striking feature of the local rank procedure is that its pronounced efficiency gain comes with only a little loss when the random error actually has a normal distribution, for which the ARE of the local rank regression estimator relative to the local linear least squares estimator is above 96% for estimating both the coefficient functions and their derivatives. For estimating the regression coefficient functions, the ARE has a sharp lower bound 88.96%, which implies that the efficiency loss is at most 11.04% in the worst case scenario. For estimating the first derivative of the regression coefficient functions, the ARE possesses a lower bound 89.91%. Kim (2008) developed a quantile regression procedure for varying coefficient models when the random errors are assumed to have a certain quantile equal to zero. She used the regression splines method and derived the convergence rate, but the lack of asymptotic normality result does not allow the comparison of the relative efficiency. On the other hand, one may extend the local quantile regression approach (Yu and Jones, 1998) to the varying coefficient models. However, this is expected to yield an estimator which still suffers from loss of efficiency and may have near zero ARE relative to the local linear least squares estimator in the worst case scenario.

The new estimator proposed in this paper minimizes a convex objective function based on local ranks. The implementation of the minimization can be conveniently carried out using existing functions in the R statistical software package via a simple algorithm (§4.1). The objective function has the form of a generalized U-statistic whose kernel varies with the sample size. Under some mild conditions, we establish the asymptotic representation of the proposed estimator and further prove its asymptotic normality. We derive the formula of the asymptotic relative efficiency of the local rank estimator relative to the local linear least squares estimator, which confirms the efficiency advantage of the local rank approach. We also extend a resampling approach, which perturbs the objective function repeatedly, to the generalized U-statistics setting; and demonstrate that it can accurately estimate the asymptotic covariance matrix.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the local rank procedure for estimating the varying coefficient models. Section 3 discusses its large sample properties and proposes a resampling method for estimating the asymptotic covariance matrix. In Section 4, we address issues related to practical implementation and present Monte Carlo simulation results. We further illustrate the proposed procedure via analyzing an environment data set. Regularity conditions and technical proofs are presented in the Appendix.

2 Local rank estimation procedure

Let Y be a response variable, and U and X be the covariates. The varying coefficient model is defined by

| (1) |

where a0(·) and a(·) are both unknown smooth functions. The random error ε has probability density function g(·) which has finite Fisher information, i.e., ∫ {g(x)}−1 g′(x)2dx < ∞. In this paper, it is assumed that U is a scalar and X is a p-dimensional vector. The proposed procedures can be extended to the case of multivariate U with more complicated notations by following the same idea in this paper.

Suppose that {Ui, Xi, Yi}, i = 1, …, n, is a random sample from model (1). Write Xi = (Xi1, …, Xip)T and a(·) = (a1(·), …, ap(·))T. For u in a neighborhood of any given u0, we locally approximate the coefficient function by a Taylor expansion

| (2) |

Denote α1 = a0(u0), , βm = am(u0) and , for m = 1, …, p. Based on the above approximation, we obtain the residual for estimating Yi at Ui = u0

| (3) |

We define the local rank objective function to be

| (4) |

where β = (β1, …, βp, βp+1, …, β2p)T, and for a given kernel function K(·) and a bandwidth h, Kh(t) = h−1K(t/h). Note that Qn(β, α2) does not depend on α1 because α1 is canceled out in ei − ej. The objective function Qn(β, α2) is a local version of Gini’s mean difference, which is a classical measure of concentration or dispersion (David, 1998). Without the kernel functions, [n(n − 1)]−1 Σ1 ≤ i, j ≤ n|ej − ej| is the global rank objective function that leads to the classical rank estimator in linear models based on Wilcoxon scores. Rank-based statistical procedures have played a fundamental role in nonparametric analysis of linear models due to its high efficiency and robustness. We refer to the review paper of McKean (2004) for many useful references.

For any given u0, minimizing Qn(β, α2) yields the local Wilcoxon rank estimator for , where . Denote the minimizer of Qn(β, α2) by (β̂T, α̂2)T. Then for m = 1, …, p,

In the sequel, we also use the vector notation α̂(u0) = (â1(u0), …, âp(u0))T and when convenient.

The location parameter a0(u0) needs to be estimated separately. This is analogous to the scenario of global rank estimation of intercept in the linear regression model. In order to make the intercept identifiable, it is essential to have additional location constraint on the random errors. We adopt the commonly used constraint that εi has median zero. Given (β̂T, α̂2)T, we estimate a0(u0) by α̂1, the value of α1 that minimizes

| (5) |

which is a local version of a weighted L1-norm objective function.

3 Theoretical Properties

3.1 Large sample distributions

In this subsection, we investigate the asymptotic properties of β̂ and α̂2. The main challenge comes from the non-smoothness of the objective function Qn(β, α2). To overcome this difficulty, we first derive an asymptotic representation of β̂ and α̂2 via a quadratic approximation of Qn(β, α2), which holds uniformly in a local neighborhood of the true parameter values. Aided with this asymptotic representation, we further establish the asymptotic normality of the local rank estimator.

Let us begin with some new notation. Let γn = (nh)−1/2, and define

Let be the value of that minimizes the following reparametrized objective function

| (6) |

Where . Let H = diag(1, h)⊗Ip, where ⊗ denotes the operation of Kronecker product and Ip denotes a p × p identity matrix. Then it can be easily seen that

We next show that the non-smooth function can be locally approximated by a quadratic function of . Let μi = ∫ tiK(t)dt, i = 1, 2, and νi = ∫ tiK2(t)dt, i = 0, 1, 2. In this paper, we assume that the kernel function K(·) is symmetric. This is not restrictive considering that most of the commonly used kernel functions, such as the Epanechnikov kernel K(t) = 0.75(1 − t2)I(|t| < 1), are symmetric. We use to denote the gradient function of , i.e., and . More specifically,

and

Furthermore, we consider the following quadratic function of :

| (7) |

where

| (8) |

, 0 denotes a matrix (or vector) of zeroes whose dimension is determined by the context, τ = ∫ g2(t)dt is the Wilcoxon constant, and g(·) is the density function of the random error ε.

Lemma 3.1

Suppose that Conditions (C1) — (C4) in the Appendix hold. Then ∀ ε > 0, ∀ c > 0,

where || · || denotes the Euclidean norm.

Lemma 3.1 implies that the non-smooth objective function can be uniformly approximated by a quadratic function in a neighborhood around 0. In the appendix, it is also shown that the minimizer of is asymptotically within a o(1) neighborhood of . This further allows us to derive the asymptotic distribution.

The local linear Wilcoxon estimator of a(u0) = (a1(u0), …, ap(u0))T is â(u0). The theorem below provides an asymptotic representation of â(u0) and the asymptotic normal distribution. Let , where Sn11(0, 0) and Sn12(0, 0) are both p × 1 vectors.

Theorem 3.2

Suppose that Conditions (C1) — (C4) in the Appendix hold. Then we have the following asymptotic representation

| (9) |

where f(u) is the density function of U. Furthermore,

| (10) |

in distribution, where .

Remark

For the estimators of the derivatives of the coefficient functions, we have the following asymptotic representations:

| (11) |

| (12) |

Following similar proof as that for Theorem 3.2 in the appendix, it can be shown that and are both asymptotically normal. The proof of the asymptotic normality of α̂2 and â′(u0) is given in the technical report version of this paper ((Wang, Kai and Li, 2009).

3.2 Asymptotic relative efficiency

We now compare the estimation efficiency of the local rank estimator (denoted by b âR(u0)) with that of the local linear least squares estimator (denoted by âLS(u0)) for estimating a(u0) in the varying coefficient model. To measure efficiency, we consider both the asymptotic mean squared error (MSE) at a given u0 and the asymptotic mean integrated squared error (MISE). When evaluating both criteria, we plug in the theoretical optimal bandwidth.

Zhang and Lee (2000) gives the asymptotic MSE of âLS(u0) for estimating a(u0):

where σ2 = var(ε) is assumed to be finite and positive. Thus, the theoretical optimal bandwidth, which minimizes the asymptotic MSE of âLS(u0), is

| (13) |

From (10), the asymptotic MSE of the local rank estimator âR(u0) is

The theoretical optimal bandwidth for the local rank estimator thus is

| (14) |

This allows us to calculate the local asymptotic relative efficiency.

Theorem 3.3

The asymptotic relative efficiency of the local rank estimator to the local linear least squares estimator for a(u0) is

This asymptotic relative efficiency has a lower bound 0.8896, which is attained at the random error density .

Remark 1

Alternatively, we may consider the asymptotic relative efficiency obtained by comparing the MISE, which is defined as MISE(h) = ∫ E||â(u) − a(u)||2w(u) du with a weight function w(·). This provides a global measurement. Interestingly, it leads to the same relative efficiency. This follows by observing that the theoretical optimal global bandwidths for the local linear least squares estimator and the local rank estimator are

| (15) |

and

| (16) |

respectively. Thus, with the theoretical optimal bandwidths,

Define φ = (12σ2τ2)4/5. Then ARE(u0) = ARE = φ.

Note that the above ARE is closely related to the asymptotic relative efficiency of the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney rank test in comparison with the two-sample t-test. Table 1 depicts the value of φ for some commonly used error distributions. It can be seen that the desirable high efficiency of traditional rank methods for estimating a finite-dimensional parameter completely carries over to the local rank method for estimating an infinite dimensional parameter.

Table 1.

Asymptotic Relative Efficiency

| Error | Normal | Laplace | t3 | Exponential | Log N | Cauchy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ | 0.9638 | 1.3832 | 1.6711 | 2.4082 | 4.9321 | ∞ |

| ψ | 0.9671 | 1.3430 | 1.5949 | 2.2233 | 4.2661 | ∞ |

By a similar calculation, we can show that the asymptotic relative efficiencies of the local rank estimator to the local linear estimator for a′(u0) and a′(·) both equal ψ = (12σ2τ2)8/11, which has a lower bound 0.8991. This value is also reported in Table 1 for some common error distributions.

Remark 2

We may also apply the local median approach (Yu and Jones, 1998) to estimate the coefficient functions and their first derivatives. Similarly, we can prove that such estimators are asymptotically normal. The ARE of the local median estimator versus the local linear least squares estimator is closely related to that of the sign test versus the t-test. It is known that the ARE of the sign test versus the t-test for the normal distribution is 0.63. Thus we expect the efficiency loss of the local median procedure to be substantial for normal random error.

3.3 Asymptotic normality of α̂1

Following (5), is the value of that minimizes

Similarly as Lemma 3.1, we can establish the following local quadratic approximation which holds uniformly in a neighborhood around 0:

| (17) |

where

| (18) |

This further leads to an asymptotic representation of α̂1:

| (19) |

The theorem below gives the asymptotic distribution of α̂1.

Theorem 3.4

Under the conditions of Theorem 3.2, we have

3.4 Estimation of the standard errors

To make statistical inference based on the local rank methodology, one needs to estimate the standard error of the resulting estimator. As indicated by Theorem 3.2, the asymptotic covariance matrix of the local rank estimator is rather complex and involves unknown functions. Here we propose a standard error estimator using a simple resampling method proposed by Jin, Ying and Wei (2001).

Let V1, …, Vn be independent and identically distributed nonnegative random variables with mean 1/2 and variance 1. We consider a stochastic perturbation of (4):

| (20) |

where ei is defined in (3). In Q̄n(β, α2), the data {Yi, Ui, Xi} are considered to be fixed, and the randomness comes from the Vi’s. Let (β̄T, ᾱ2)T be the value of (βT, α2)T that minimizes Q̄n(β, α2). It is easy to obtain (β̄T, ᾱ2)T by applying a simple algorithm described in Section 3.1.

Jin, Ying and Wei (2001) established the validity of the resampling method when the objective function has a U-statistics structure. Although their theory covers many important applications, they require that the U-statistic has a fixed kernel. We extend their result to our setting, where the U-statistic involves variable kernel due to nonparametric smoothing. Let ā(u0) be the local rank estimator of a(u0) based on the perturbed objective function (20), i.e., it is the subvector that consists of the first p components of β̄. Its asymptotic normality is given in the theorem below.

Theorem 3.5

Under the conditions of Lemma 3.1, conditional on almost surely every sequence of data {Yi; Ui; Xi},

in distribution.

This theorem suggests that to estimate the asymptotic covariance matrix of b â(u0), one can repeatedly perturb (4) by generating a large number of independent random samples . For each perturbed objective function, one solves for ā(u0). The sample covariance matrix of ā(u0) based on a large number of independent perturbations provides a good approximation. The accuracy of the resulting standard error estimate will be tested in the next section.

The perturbed estimator has conditional bias equal to zero. It has been found that standard bootstrap method, which resamples from the empirical distribution of the data, also estimates bias as zero when estimating nonparametric curves (Hall and Kang, 2001). It is possible to use more delicate bootstrap technique to estimate the bias of a nonparametric curve estimator. Although some of the ideas may be adapted to the method of disturbing the objective function, this is beyond the scope of our paper and is not pursued further here.

4 Numerical Studies

4.1 A pseudo-observation algorithm

The local rank estimator can be obtained by applying an efficient and reliable algorithm. Note that the local rank estimator of can be solved by fitting a weighted L1 regression on pseudo observations ( , Yi-Yj) with weights wij = K((Ui − u0)/h)K((Uj − u0)/h), where , 1 ≤ i < j ≤ n. Given (β̂T, α̂2)T, the estimator of a0(u0) can be obtained by another weighted L1 regression on (1, ) With weights wi = K((Ui − u0)/h), 1 ≤ i ≤ n. Many statistical software packages can implement weighted L1 regression. In our numerical studies, we use the function “rq” in the R package quantreg.

4.2 Bandwidth selection

Bandwidth selection is an important issue for all statistical models that involve nonparametric smoothing. Although we have derived the theoretical optimal bandwidth for the local rank estimator in (14) and (16), it is difficult to use the “plug-in“ method to estimate it due to many unknown quantities.

We propose below an alternative bandwidth selection method that is practically feasible. This approach is based on the relationship between and . From Section 2.3, we see that

| (21) |

Thus, we can first use existing bandwidth selectors (e.g. Zhang and Lee 2000) to estimate or . The error variance σ2 can be estimated based on the residuals; in particular when robustness is of concern it can be estimated using the MAD of the residuals. Hettmansperger and Mckean (1998, p.181) discussed in details how to estimate τ, which can be obtained by the function “wilcoxontau” in the R software developed by Terpstra and McKean (2005). In the end, we plug in these estimators into (21) to get the bandwidth for local rank estimator.

Alternatively, instead of the above two-step procedure, we may directly use the computationally intensive cross-validation to estimate the bandwidth for the local rank procedure. Note that under outlier contamination, standard cross-validation can lead to extremely biased bandwidth estimates because it can be adversely influenced by extreme prediction errors. Robust cross-validation method, such as that developed by Leung (2005), is therefore preferred.

4.3 Examples

We conduct Monte Carlo simulations to access the finite sample performance, and illustrate the proposed methodology on a real environmental data set. In the analysis, we use the Epanechnikov kernel K(u) =.75(1 − u2)I(|u| < 1).

Example 1

We generate random data from

where a0(u) = exp(2u − 1), a1(u) = 8u(1 − u) and a2(u) = 2 sin2(2πu). The covariate U follows a uniform distribution on [0, 1], and is independent from (X1, X2), where the covariates X1 and X2 are standard normal random variables with correlation coefficient 2−1/2. The coefficient functions and the mechanism to generate U and (X1, X2) are the same as those in Cai, Fan and Li (2000). We consider six different error distributions: N(0, 1), Laplace, standard Cauchy, t-distribution with 3 degrees of freedom, mixture of normals 0.9N(0, 1) + 0.1N(0, 102) and lognormal distribution. Except for Cauchy error, all the other generated random errors are standardized to have median 0 and variance 1. We consider sample sizes n =400 and 800, and conduct 400 simulations for each case.

We compare the performance of the local rank estimate with the local least squares estimate using the square root of average squared errors (RASE), defined by

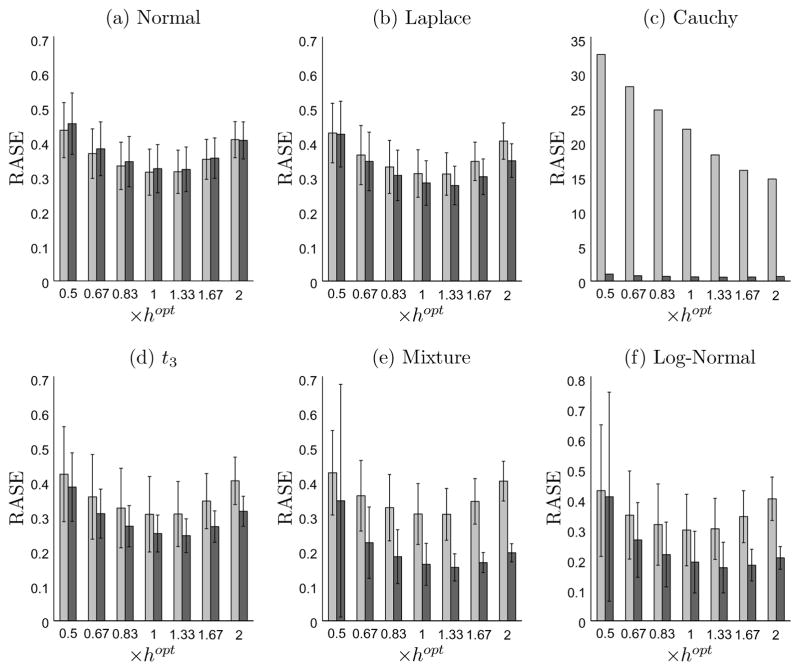

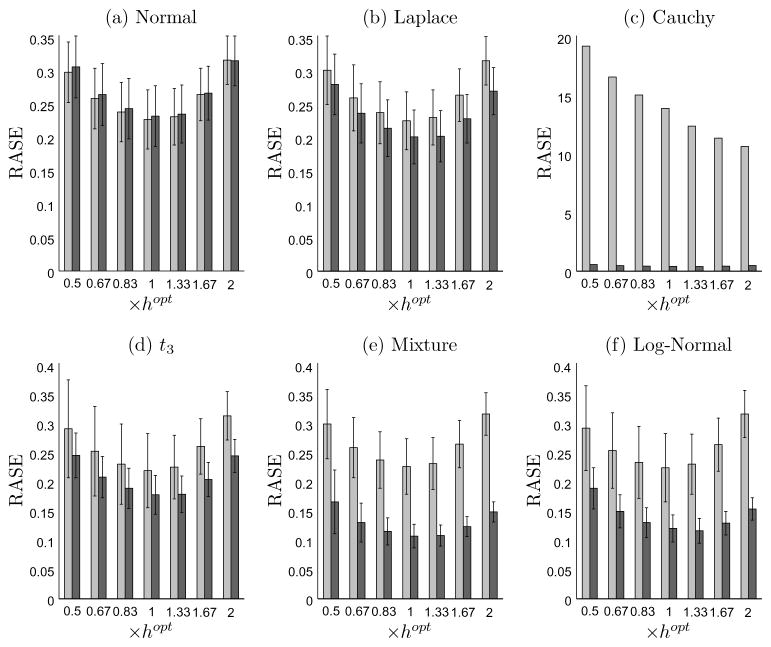

where {uk: k = 1, ···, ngrid} is a set of grid points uniformly placed on [0, 1] with ngrid = 200. The sample mean and standard deviation of the RASEs over 400 simulations are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2, for sample size n = 400 and 800, respectively. The two figures clearly demonstrate that the local rank estimator performs almost as well as the local least squares estimator for normal random error; and has smaller RASE for other heavier-tailed error distributions. The efficiency gain can be substantial, see for example the mixture normal case where the observed relative efficiency for the local rank estimator versus the local least squares estimator is above 2 for most choices of bandwidth. For Cauchy random error, the local rank estimator yields a -consistent estimator but the local least squares estimator is inconsistent, which is reflected by the extremely large value of RASE for the local least squares estimator.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs of the RASE with standard error for sample size n = 400 over 400 simulations. The light gray bar denotes the local least squares method and the dark gray bar denotes the local rank method. The horizontal axis is in the unit of hopt, which is calculated separately for each method and error specification using either (13) or (14).

Figure 2.

Bar graphs of the RASE with standard error for sample size n = 800 over 400 simulations. The light gray bar denotes the local least squares method and the dark gray bar denotes the local rank method. The horizontal axis is in the unit of hopt, which is calculated separately for each method and error specification using either (13) or (14).

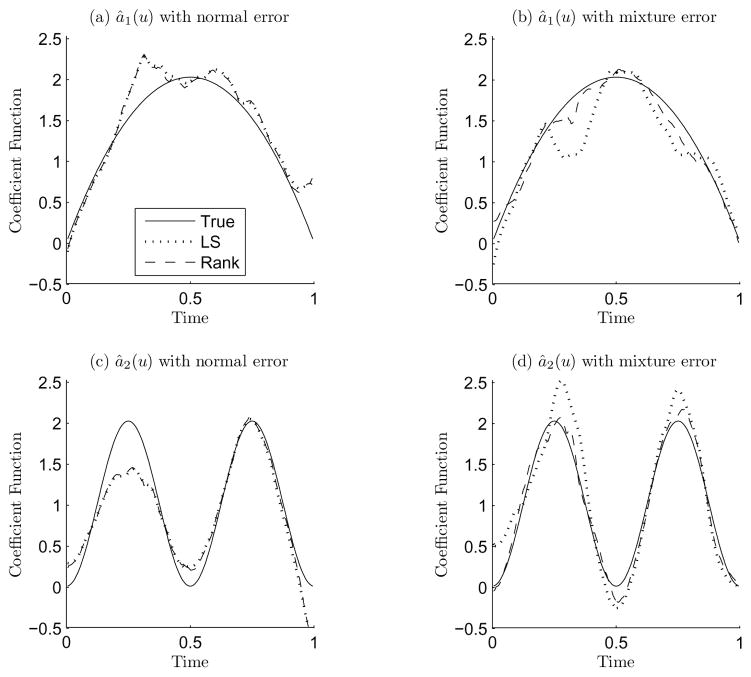

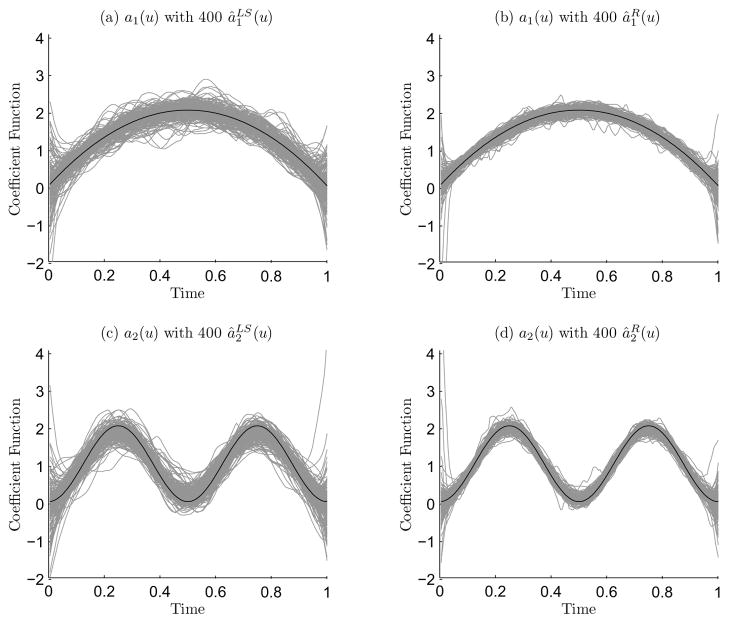

Figure 3 depicts the estimated coefficient functions for the normal random error and the mixture normal random error for a typical sample, which is selected in such a way that its RASE value is the median of the 400 RASE values. For this typical sample, we observe that the local rank estimator is almost identical to the local least squares estimator for normal random error; but falls much closer to the truth than the local least squares estimator does for mixture normal random error. Figure 4 plots the estimated coefficient functions for all 400 simulations when the random error has a mixture of normal distribution. It is clear that the local rank estimator has smaller variance. In these two figures, we set the bandwidth to be the theoretic optimal one hopt, calculated using (15) and (16), for both the local rank estimator and the local least squares estimator.

Figure 3.

Plot of estimated coefficient functions for a typical data set

Figure 4.

(a) and (c) are plots of 400 local least squares estimators of a1(·) and a2(·) over 400 simulation, respectively. (b) and (d) are plots of 400 local rank estimators of a1(·) and a2(·), respectively.

At the end, we evaluate the resampling method (Section 3.4) for estimating the standard errors. We randomly perturb the objective function 1000 times; each time the random variables Vi in (20) are generated from the Gamma(0.25, 2) distribution. Table 2 summarizes the simulation results at three points u0 = 0.25, 0.50 and 0.75. In the table, ‘SD’denotes the standard deviation of 400 estimated âm(u0) and can be regarded as the true standard error; ‘SE(std(SE))’ denotes the mean (standard deviation) of 400 estimated standard errors from the resampling method. Bandwidths are set to be the optimal ones. We observe that the resampling method estimates the standard error very accurately.

Table 2.

Standard deviations of the local rank estimators with n = 400

|

â1(u) |

â2(u) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error | u0 | SD | SE(Std(SE)) | SD | SE(Std(SE)) |

| Normal | 0.25 | 0.189 | 0.159(0.032) | 0.197 | 0.160(0.032) |

| 0.5 | 0.183 | 0.159(0.030) | 0.180 | 0.162(0.031) | |

| 0.75 | 0.191 | 0.162(0.033) | 0.195 | 0.163(0.032) | |

| Laplace | 0.25 | 0.175 | 0.151(0.037) | 0.174 | 0.151(0.037) |

| 0.5 | 0.168 | 0.153(0.039) | 0.173 | 0.154(0.039) | |

| 0.75 | 0.168 | 0.150(0.037) | 0.177 | 0.150(0.037) | |

| Mixture | 0.25 | 0.095 | 0.107(0.051) | 0.092 | 0.107(0.049) |

| 0.5 | 0.095 | 0.109(0.057) | 0.091 | 0.109(0.055) | |

| 0.75 | 0.095 | 0.108(0.061) | 0.093 | 0.109(0.055) | |

| t3 | 0.25 | 0.144 | 0.137(0.039) | 0.145 | 0.138(0.036) |

| 0.5 | 0.148 | 0.133(0.035) | 0.152 | 0.136(0.037) | |

| 0.75 | 0.158 | 0.137(0.039) | 0.155 | 0.139(0.042) | |

| Log N | 0.25 | 0.111 | 0.112(0.047) | 0.112 | 0.114(0.049) |

| 0.5 | 0.106 | 0.114(0.047) | 0.107 | 0.119(0.050) | |

| 0.75 | 0.118 | 0.117(0.058) | 0.118 | 0.120(0.060) | |

Example 2

As an illustration, we now apply the local rank procedure to the environmental data set in Fan and Zhang (1999). Of interest is to study the relationship between levels of pollutants and the number of total hospital admissions for circulatory and respiratory problems on every Friday from January 1, 1994 to December 31, 1995. The response variable is the logarithm of the number of total hospital admissions, and the covariates include the level of sulfur dioxide (X1), the level of nitrogen dioxide (X2) and the level of dust (X3). A scatter plot of the response variable over time is given in Figure 5(a). We analyze this data set using the following varying coefficient model

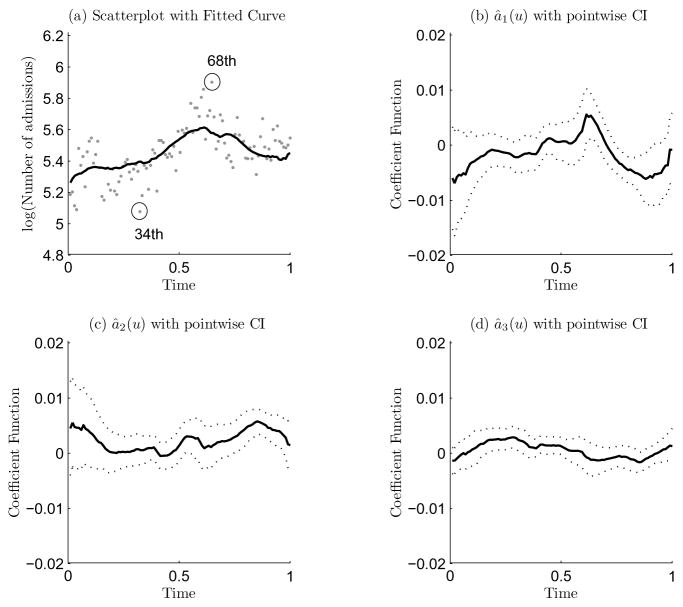

Figure 5.

(a) Scatterplot of the log of number of total hospital admissions over time, and the solid curve is an estimator of the expected log of number of hospital admissions over time at the average pollutant levels, i.e., â0(u) + â1(u)X̄1 + â2(u)X̄2 + â3(u)X̄3, (b), (c) and (d) are the estimated coefficient functions via the local rank estimator for ak(·), k = 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

where u denotes time and is scaled to the interval [0,1].

We select the bandwidth via the relation (21). More specifically, we first use 20-fold cross-validation to select a bandwidth ĥLS for the local least squares estimator. We then use the function ‘wilcoxontau’ in the R package for rank regression by Terpstra and McKean to estimate (12τ2)−1/2 and use the MAD of the residuals to robustly estimate σ. All these lead to the selected bandwidth for the local rank estimator: ĥR = 0.26.

The estimated coefficient functions are depicted in Figures 5(b), (c) and (d), where the two dashed curves around the solid line are the estimated function plus/minus twice the standard errors estimated by the resampling method. These two dashed lines can be regarded as a pointwise confidence interval with bias ignored. The figures suggest clearly that the coefficient functions vary with time. The fitted curve is shown in Figure 5(a).

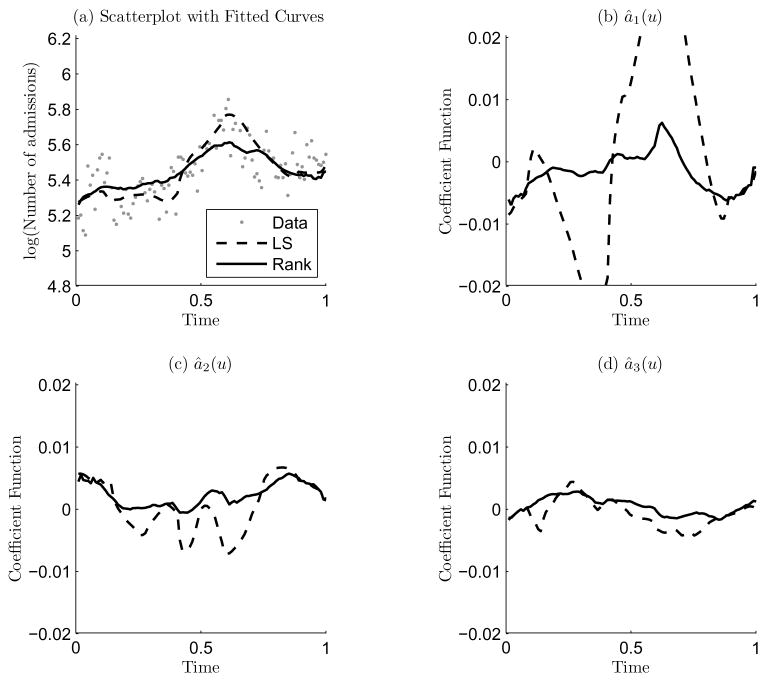

Now we demonstrate the robustness of the local rank procedure. To this end, we artificially perturb the dataset by moving the response value of the 68th observation from 5.89 to 6.89, and the response value of the 34th observation from 5.07 to 3.07. We refit the data with both the local least squares procedure and the local rank procedure, see Figure 6. We observe that the local least squares estimator changes dramatically due to the presence of these two artificial outliers. In contrast, the local rank estimator is nearly unaffected.

Figure 6.

(a) Scatterplot of the perturbed data (without the two outliers shown as they are outside of the range), and the local LS and the local rank estimators of the expected log of number of hospital admissions. (b), (c) and (d) are the local LS and the rank estimators of the coefficient functions for ak(·), k = 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Appendix: Proofs

Regularity conditions

(C1). Assume that {Ui, Xi, Yi} are independent and identically distributed, and that the random error ε and the covariate {U, X} are independent. Furthermore, assume that ε has probability density function g(·) which has finite Fisher information, i.e., ∫{g(x)}−1g′(x)2dx < ∞; and that U has probability density function f(·).

(C2). The function am(·), m = 0, 1,…, p, has continuous second-order derivative in a neighborhood of u0.

-

(C3). Assume that E(Xi|Ui = u0) = 0 and that is continuous at u = u0. The matrix Σ(u0) is positive definite.

(C4). The kernel function K(·) is symmetric about the origin, and has a bounded support. Assume that h → 0 and nh2 → ∞, as n → ∞

These conditions are used to facilitate the proofs, but may not be the weakest ones. The assumptions on the random errors in (C1) are the same as those for multiple linear rank regression (Hettmansperger and McKean, 1998). (C2) imposes smoothness requirement on the coefficient functions. In (C3), the assumption E(Xi|Ui = u0) = 0 (also adopted by Kim, 2007) makes the presentation simpler but can be relaxed. It can be shown that the asymptotic normality still holds without this assumption. The conditions on the kernel function and bandwidth in (C4) are common for nonparametric kernel smoothing.

In our proofs, we will use some results on generalized U-statistic, where the kernel function is allowed to depend on the sample size n. The generalized U-statistic has the form Un = [n(n − 1)]−1ΣΣi≠j Hn(Di, Dj), where is a random sample and Hn is symmetric in its arguments, i.e., Hn(Di, Dj) = Hn(Dj, Di). In this paper, . Define rn(Di) = E[Hn(Di, Dj)|Di], r̄n = E[rn(Di)] and . We will repeatedly use the following lemma taken from Powell, Stock and Stoker (1989).

Lemma A.1

If E[||Hn(Di, Dj)||2] = o(n), then and Un = r̄n + op(1).

We need the following two lemmas to prove Lemma 3.1. Denote

and define

Lemma A.2

Suppose that Conditions (C1) — (C4) hold, then An → A, where A is defined in (8).

Proof

We can write . Let

Calculating the expectation by conditional on Ui and Uj first, An11 becomes

Using Condition (C3), straightforward calculation gives . Let

Using Condition (C3) and notice that K(·) is symmetric, it can be shown that . By symmetry, . Similarly, we have

Thus . Similarly, we can show that , and

Lemma A.3

Under Conditions (C1) — (C4), we have

Proof

Let , where

Let Hn(Di, Dj) = [Wn(Di, Dj)+Wn(Dj, Di)]/2, then Un = [n(n − 1)]−1 ΣΣi≠j Hn(Di, Dj) has the form of a generalized U-statistic. Note that . Furthermore,

Thus Un = E[Hn(Di, Dj)] + op(1) by Lemma A.1. Furthermore,

The proof is completed by using Lemma A.2.

Proof of Lemma 3.1

In view of Lemma A.3, it follows that

The proof follows along the same lines of the proof of Theorem A.3.7. of Hettmansperger and McKean (1998), using a “diagonal subsequencing” argument and convexity.

Proof of Theorem 3.2

By Lemma 3.1, , where uniformly over any bounded set. Note that is minimized by , and Bn(s1, s2) is minimized by . We first establish the asymptotic representation by following similar argument as in Hjort and Pollard (1993). For any constant c > 0, define

then as n → ∞. Let be an arbitrary point outside the ball { }, then we can write , where l > c is a positive constant and 1d denotes a unit vector of length d. Write

By the convexity of , we have

Thus,

If , then for all outside the ball. This implies if then the minimizer of must be inside the ball. Thus

where λ is the smallest eigenvalue of A. Therefore, . This in particular implies the asymptotic representations (9), (11) and (12).

We next show the asymptotic normality of â(u0). From (9), we have

| (A.1) |

where

| (A.2) |

By (A.2), let us rewrite , where

We next prove that

| (A.3) |

Note that we can write , where Hn(Di, Dj) =Wn(Di, Dj) + Wn(Dj, Di) with

Similarly to the arguments in the proof of Lemma A.3, it can be shown that E[||Hn(Di, Dj)||2] = o(n). By Lemma A.1, this implies that since it is easy to check that r̄n = 0. We have

Furthermore,

To prove the asymptotic normality of Sna(0, 0), it is sufficient to check the Lindeberg-Feller condition: ∀ ε > 0, . This can be easily verified by applying the dominated convergence theorem. Next we show that

| (A.4) |

We may write , where with

Note that

By applying Lemma A.1, it can be shown that . It follows by using the same arguments as those in the proof of Lemma A.2 that

This proves (A.4). By combining (A.3) and (A.4) and using the approximation given in (A.1), we obtain (10).

Proof of Theorem 3.3

A result of Hodges and Lehmann (1956) indicates that the ARE has a lower bound 0.8644/5 = 0.8896, with this lower bound being attained at the density .

Proof of Theorem 3.4

Let

where , ξ1 ∈ ℝ, ξ2 ∈ ℝp and ξ3 ∈ ℝp. The subgradient of with respect to is

We have , which is the same as the Sn0 defined in (18). Let , then

For any positive constants ci, i = 1, 2, 3 and ∀ ξ1, ξ2, ξ3 such that ||ξ1|| ≤ c1h−1γn, ||ξ2|| ≤ c2γn and ||ξ3|| ≤ c3h−1γn, we have

| (A.5) |

This can be proved by directly checking the mean and variance. More specifically,

And

By (A.5) and similar proof as that for Lemma 3.1, we have

| (A.6) |

where . Because the function is convex in its arguments, (A.6) can be strengthened to uniform convergence (convexity lemma, see Pollard 1991), i.e.,

where ℂ is a compact set in ℝ. By Theorem 3.2, , â(u0) − a(u0) = Op(γn) and â′ (u0) − a′(u0) = Op(h−1γn), we thus have

Note that , where and Sn0 are defined in Section 2.4. The quadratic function is minimized by . Similar argument as that for Theorem 3.2 shows that . Thus we have (19). We can write , where

By the Lindeberg-Feller central limit theorem, T1n → N (0, f (u0)ν0/3) in distribution. By checking mean and variance, we have

Combining the above results and using (19), the proof is completed.

To prove Theorem 3.5, we first extend Lemma A.1 to almost sure convergence.

Lemma A.4

If E[||Hn(Di, Dj)||2] = O(h−2), then Un − Ûn = o(1) almost surely and Un = r̄n + o(1) a.s.

Proof

The proof of Powell, Stock and Stoker (1989) for Lemma A.1 suggests that E[||Un − Ûn||2] = O(n−2h−2). By Theorem 1.3.5 of Serfling (1980), . This implies that Un − Ûn = o(1) almost surely. The second result follows by an application of the strong law of large numbers to Ûn.

Proof of Theorem 3.5

Let β* and be defined the same as before. We introduce the reparametrized objective function . Let denote the gradient function of , which is defined similarly as in Section 2.2. We first show that has a similar local linear approximation as stated in Lemma A.3. To make the proof concise, we prove this for , where

Let , where and

Note that . Conditional on , this is a weighted average of Vi. Note that

By Lemma A.4, it can be shown that almost surely, where A* = 4τf2(u0)diag(Ip,μ2Ip) ⊗ Σ(μ0). It is also easy to check that almost surely. Thus for almost surely every sequence , Un=γnA*β*+op(1), where op(1) is in the probability space generated by . The proofs of Lemma 3.1 and the asymptotic representation in Theorem 3.2 can be similarly carried out to show that for almost surely every sequence ,

| (A.7) |

where op(1) is in the probability space generated by , and

The approximation (A.1) can be strengthened to almost surely convergence, i.e.,

| (A.8) |

Combining (17) and (A.7), we have that for almost surely every sequence ,

Note that

And . We have

where

Lemma A.4 can be used to show that W1 = o(1) almost surely; and a minor extension of Lemma A.4 to third-order U-statistic can be used to show that almost surely. The asymptotic normality of follows by showing that the condition of Lindeberg-Feller central limit theorem for triangular arrays holds almost surely. We have, for almost surely every sequence ,

in distribution. This completes the proof.

Footnotes

Lan Wang is Assistant Professor, School of Statistics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455. Email: lan@stat.umn.edu. Bo Kai is a graduate student, Department of Statistics, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802. Email: bokai@psu.edu. Runze Li is Professor, Department of Statistics and The Methodology Center, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-2111. Email: rli@stat.psu.edu. Wang’s research is supported by National Science Foundation grant DMS-0706842. Kai’s research is supported by National Science Foundation grants DMS 0348869 as a research assistant. Li’s research is supported by NIDA, NIH grants R21 DA024260 and P50 DA10075. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDA or the NIH.

References

- 1.Brumback B, Rice JA. Smoothing Spline Models for the Analysis of Nested and Crossed Samples of Curves (with discussion) Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1998;93:961–994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai Z, Fan J, Li R. Efficient Estimation and Inferences for Varying- Coefficient Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2000;95:888–902. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleveland WS, Grosse E, Shyu WM. Local regression models. In: Chambers JM, Hastie TJ, editors. Statistical Models in S. Pacific Grove, California: Wadsworth & Brooks; 1992. pp. 309–376. [Google Scholar]

- 4.David HA. Early Sample Measures of Variability. Statistical Science. 1998;13:368–377. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan J, Li R. An Overview on Nonparametric and Semiparametric Techniques for Longitudinal Data. In: Fan J, Koul H, editors. Frontiers in Statistics. Imperial College Press; London: 2006. pp. 277–303. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan J, Zhang W. Statistical Estimation in Varying-Coefficient Models. The Annals of Statistics. 1999;27:1491–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan J, Zhang W. Simultaneous Confidence Bands and Hypothesis Testing in Varying-Coefficient Models. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 2000;27:715–731. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan J, Zhang W. Statistical Methods with Varying Coefficient Models. Statistics and its Interface. 2008;1:179–195. doi: 10.4310/sii.2008.v1.n1.a15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall P, Kang KH. Bootstrapping Nonparametric Density Eestimators with Empirically Chosen Bandwidths. The Annals of Statistics. 2001;29:1443–1468. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastie TJ, Tibshirani RJ. Varying-Coefficient Models (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1993;55:757–796. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hettmansperger TP, McKean JW. Robust Nonparametric Statistical Methods. London: Arnold; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hjort NL, Pollard D. Asymptotics for minimisers of convex processes, Preprint. 1993 http://citeseer.ist.psu.edu/hjort93asymptotics.html.

- 13.Hodges JL, Lehmann EL. The Efficiency of Some Nonparametric Competitors of the t-Test. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1956;27:324–335. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoover DR, Rice JA, Wu CO, Yang L-P. Nonparametric Smoothing Estimates of Time-varying Coefficient Models with Longitudinal Data. Biometrika. 1998;85:809–822. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Z, Ying Z, Wei LJ. A Simple Resampling Method by Disturbibg the Minimand. Biometrika. 2001;88:381–390. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kauermann G, Tutz G. On Model Diagnostics Using Varying Coefficient Models. Biometrika. 1999;86:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M-O. Quantile Regression with Varying Coefficients. The Annals of Statistics. 2007;35:92–108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung DH. Cross-validation in nonparametric regression with outliers. The Annals of Statistics. 2005;33:2291–2310. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKean JW. Robust Analysis of Linear Models. Statistical Science. 2004;19:562–570. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard D. Asymptotics for Least Absoulte Deviation Regression Estimators. Econometric Theory. 1991;7:186–199. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell JL, Stock JH, Stoker TM. Semiparametric Estimation of Index Coefficients. Econometrica. 1989;57:1403–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serfling R. Approximation Theorems of Mathematical Statistics. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terpstra J, McKean J. Rank-based Analysis of Linear Models using R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2005;14:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Kai B, Li R. Technical Report, the Methodology Center, the Pennsylvania State University. 2009. Local Rank Inference for Varying Coefficient Models. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CO, Chiang CT, Hoover DR. Asymptotic Confidence Regions for Kernel Smoothing of a Varying-coefficient Model with Longitudinal Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1998;93:1388–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu K, Jones MC. Local Linear Quantile Regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1998;93:228–237. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang W, Lee SY. Variable Bandwidth Selection in Varying-Coefficient Models. Journal of Multivariate Analysis. 2000;74:116–134. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.