Abstract

Objectives

Prior research suggests possible gender differences in the longitudinal course of bipolar disorder (BD). This study prospectively examined gender differences in mood outcomes and tested the effects of sexual/physical abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Methods

Participants (49 men, 41 women) with co-occurring bipolar I and substance use disorders (92% alcohol, 42% drug) were enrolled in a group treatment trial. They were followed for 8 months, with monthly assessments, yielding 32 weeks of data. Primary outcome measures were number of weeks in each mood state, recurrences to depression or mania, and polarity shifts from depression to mania or vice versa. Negative binomial regression was used to examine the effects of gender, lifetime abuse, and PTSD on these outcomes.

Results

Participants met syndromal criteria for a mood episode on a mean of 27% of 32 weeks, with depression occurring most frequently. Compared to men, women reported significantly more weeks of mixed mania (RR = 8.53), fewer weeks of euthymia (RR = 0.58), more recurrences to mania (RR = 1.96), and more direct polarity shifts (RR = 1.49) (all p < .05). Women also reported significantly higher rates of lifetime sexual or physical abuse (68% vs. 33%), which partially explained the relationships between gender and mixed mania and direct polarity shifts.

Conclusions

Participants experienced persistent mood symptoms over time. Women consistently reported poorer mood outcomes, and lifetime abuse may help explain observed gender differences in mood outcomes. Further research is necessary to better understand the treatment implications of these findings.

Prior research suggests that there may be gender differences in the longitudinal course of bipolar disorder (BD). In a nationally representative sample of individuals with BD, women were more likely to have experienced both mixed and depressive episodes, while men were more likely to have experienced manic episodes only (1). Multiple observational studies of BD patients have also found that women were more likely than men to have a history of mixed episodes (2–5). In a cross-sectional study of acutely manic patients, women were more likely than men to present at hospitalization with co-occurring dysphoric symptoms (2). In a large prospective study, women were more likely to experience depression during hypomanic episodes (6). However, three other studies found no gender differences in the mean number of lifetime depressed, manic, or mixed episodes (1, 7, 8). A number of studies have examined gender differences in rapid cycling between depression and mania, typically using retrospective designs. A majority of these studies suggest that women are more likely than men to have a history of rapid cycling (9–12), although one did not find a gender difference (7). Another study found that women were more likely than men to have eight or more mood episodes in the past year (13). In a large prospective study, women were significantly more likely than men to be rapid cyclers during the first year of follow-up (14).

In sum, the extant literature on the course of BD suggests that women may be more likely than men to experience mixed mania and rapid cycling. Inconsistencies across studies may be due to a number of methodological and sampling differences. First, many prior studies have relied on retrospective designs that are vulnerable to recall bias. For example, participants may have difficulty remembering the number of past mood episodes, their duration, or the frequency of polarity shifts, especially for episodes occurring years ago. Second, nearly two-thirds of individuals with BD I have a lifetime substance use disorder (SUD) (15). As in the general population, more men than women with BD have an SUD (16, 17). However, the risk of developing an alcohol use disorder is greater for women with BD compared to men with BD, relative to the general population (16); comparable analyses for drug use disorders have not yet been reported. Individuals with co-occurring BD and SUD, compared to those with BD alone, have been found to experience more mixed mania (18), more rapid cycling (13), more recurrences to mania (19), and less time spent in remission (20). Despite these generally poorer outcomes in patients with co-occurring SUD, there are no prospective studies describing the course of BD in a sample of patients with co-occurring BD and SUD. Furthermore, many prior studies examining gender differences have not accounted for SUD in their analyses.

Other factors not previously examined may also help to explain the relationship between gender and mood outcomes in patients with BD. First, women are more likely than men to experience sexual and physical abuse (21–24). Patients with BD report disproportionately high rates of sexual and physical abuse, with approximately half experiencing severe childhood abuse (25–27). Among BD patients, those with abuse histories are more likely to have co-occurring SUDs (16, 25, 28, 29). They are also more likely to have an earlier age of BD onset, more time spent depressed or manic, faster cycling, and more suicide attempts (13, 25, 28, 29). However, prior studies have not examined the effect of abuse history on mixed mania, mood recurrences, and polarity shifts in patients with co-occurring BD and SUD.

Second, women are more likely to develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), especially following sexual or physical abuse (30). Among patients with BD, approximately one-third have a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD (7, 15). A history of sexual or physical abuse is predictive of PTSD, but only a minority of BD patients with abuse histories develop PTSD (25, 26). In BD patients, those with PTSD are more likely to be female (7, 31) and have a co-occurring SUD (32–34). In turn, PTSD is associated with greater BD severity, more depressive symptoms, shorter euthymic periods, greater functional impairment, poorer quality of life, and more suicide attempts (26, 33, 34). However, prior studies have not examined the effect of PTSD on mixed episodes, mood recurrences, and polarity shifts in BD.

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the effects of gender, sexual/physical abuse, and PTSD on the course of BD in patients with co-occurring SUD over an 8-month period. To address the aforementioned gaps in the literature, we prospectively followed patients with co-occurring BD and SUD, interviewing them monthly to elicit weekly data on mood symptoms. Based on prior research examining predictors of affective burden in BD (18, 35–39), we examined number of weeks in each mood state, number of mood recurrences, and number of polarity shifts. We hypothesized that women would experience more weeks of mixed mania, more recurrences to mania, and more polarity shifts. We further hypothesized that a lifetime history of abuse and a diagnosis of PTSD would each predict more weeks of mixed mania, recurrences to mania, and polarity shifts, and that gender would be indirectly associated with these mood outcomes through lifetime abuse and PTSD.

Method

Participants and procedures

Data for the study were collected as part of two clinical trials of a manualized group therapy for patients with co-occurring BD and SUD (40, 41). Both research protocols were approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board and are in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Participants were recruited from McLean Hospital programs, advertisements, fliers, and clinician referrals. Inclusion criteria were current diagnoses of bipolar disorder (not substance-induced) and substance dependence other than nicotine, substance use within 60 days of intake, mood stabilizer regimen for at 2 least weeks, and 18 years of age or older. Exclusion criteria were current psychosis, current danger to self or others, concurrent group treatment, and residential treatment restricting substance use. Of the 235 who met initial screening criteria, 55 were ineligible, 57 failed to complete the assessment process, and 123 were enrolled. All participants provided written informed consent. Twenty-four participants with BD II or BD NOS were excluded from the current analysis, as only BD I patients experience manic and mixed episodes (42). An additional nine participants had no follow-up data, leaving a final sample size of 90.

The current study presents 32 weeks of data from two study cohorts. Participants in both cohorts were randomly assigned to one of two group treatments: Integrated Group Therapy (40) or Group Drug Counseling (43). The groups met weekly for 1 hour across 20 and 12 weeks in the first and second cohorts, respectively. Participants in both cohorts were assessed at baseline and then monthly for the first 6 months. The first cohort completed two additional assessments at monthly intervals, and the second cohort completed an additional assessment at month 9. Retention in the study was high: participants provided a mean of 30.37 (SD = 4.54) weeks of data, with no gender differences in retention t(88) = 0.56, p = .58).

Measures

Psychiatric diagnoses

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (44) was used to identify psychiatric disorders. The SCID is a semi-structured interview that uses a decision tree approach for lifetime and current diagnoses of many DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders. Modules A (Mood Episodes), B (Psychotic Symptoms), C (Differential Diagnosis of Psychotic Disorders), D (Mood Differential), and F (Anxiety Disorders) were administered by a doctoral- or masters-level clinician. Module E (Substance Use Disorders) was administered by a trained, supervised research assistant.

Mood symptoms

The Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE) (45) was used to assess weekly mood symptoms. The LIFE is a combination of the SCID, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (46), and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (47), and it utilizes a calendar method to assist recall. After administering these assessments, the clinical team (research assistants and clinicians) met to decide whether a participant met criteria for a mood episode based on DSM-IV criteria for each follow-up week in question. If so, the mood episode was categorized as depressed, manic, hypomanic, or mixed; distinctions were not make between substance-induced and non-substance-induced episodes). The LIFE Psychiatric Status Rating was used to describe the overall course rating for each week (48). This is a 6-point scale that is anchored to diagnostic thresholds for psychiatric disorders; 1 indicates euthymia (“usual self”), 2–4 indicate subsyndromal mood symptoms, and 5–6 indicate full syndromal mood episodes. As in previous studies (49), we examined the following mood outcomes:

Mood states were coded based on DSM-IV criteria for major depression, mania, hypomania, and mixed episodes. The number and percent of weeks in each mood state were then computed. Weeks with no mood symptoms were categorized as euthymic.

Mood recurrence was defined as a change from no mood state (≥ 1 week of euthymia or subsyndromal mood symptoms) to any mood state (≥ 1 week of depression, mania, hypomania, or mixed episode). This was further specified as recurrence to a depressive state or a manic/hypomanic/mixed state.

Polarity shift was defined as any shift between a depressive and a manic/hypomanic/mixed state, in either direction. An indirect shift was a shift with at least 1 week of euthymia or subsyndromal symptoms between the two polarities. A direct shift was a shift without a period of euthymia or subsyndromal symptoms between the two polarities.

Substance abuse

The Addiction Severity Index (50), a well validated and widely used instrument designed to measure functioning among substance abusers, was used to assess alcohol- and drug-related problems at baseline. The Timeline Follow-back technique (51), which uses a calendar to assist recall, was used to assess substance use throughout the assessment period. Urine toxicology screens were obtained to validate self-reports. The SCID was used to diagnoses SUDs.

Physical/sexual abuse and PTSD

History of physical and sexual abuse was assessed using the following two items from the Addiction Severity Index (50): “In your lifetime, has anyone ever abused you physically?” and “In your lifetime, has anyone ever abused you sexually?” The SCID was used to diagnose PTSD, and to identify index traumas precipitating PTSD.

Data analysis

Women and men were compared on demographic and psychiatric variables using Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) tests for quantitative variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Means and medians were calculated for the following mood outcomes: number of weeks in each mood state (depression, mania/hypomania, mixed mania, euthymia), number of mood recurrences (to depression and to mania/hypomania/mixed mania), and number of polarity shifts (direct and indirect). These variables were count data with non-normal distributions. Although Poisson regression is widely used to model count data, it often fails to account adequately for the true dispersion or variability in the data. Therefore, to account for potential overdispersion in the count data outcomes (i.e., excess variability relative to that predicted by Poisson count data), negative binomial regression was used to examine the effects of gender, lifetime sexual/physical abuse, and PTSD on the mood outcomes (52). To adjust appropriately for differences in the length of follow-up, follow-up time was included as an offset in the analysis; in addition, analyses controlled for study cohort and treatment condition. For both univariate and multivariable models, comparisons are expressed in terms of relative rates (RR). To test the indirect effects of gender on mood outcomes, we used a bootstrap approach that is appropriate for non-normally distributed data and relatively small sample sizes (53, 54). This method estimates the effect size and 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect, and it can be used in multiple regressor models (55, 56).

Results

The sample included 49 men and 41 women (N = 90). Participants were 18–65 years old (M = 40.6 ± 11.7), primarily Caucasian (94%), and well-educated (99% high school graduates, 56% college graduates). Most were unmarried (49% single, 17% divorced/separated, 1% widowed). Approximately half were unemployed (52%) and had an annual household income less than $50,000 (47%). For SUD diagnoses, 58% had both drug and alcohol dependence, 34% had alcohol dependence alone, and 8% had drug dependence alone. Among drug dependent participants, the most common drugs of dependence were marijuana (63%) and cocaine (56%). The mean Addiction Severity Index Alcohol Composite score was 0.40 (SD = 0.24), and the mean Addiction Severity Index Drug Composite score was 0.10 (SD = 0.11). Over the 8-month assessment period, participants reported alcohol to intoxication and drug use on a mean of 24.48 (SD = 38.06) and 22.78 (SD = 46.87) days, respectively. There were no gender differences on any of these demographic and substance use variables (all p < .05).

Participants reported high rates of lifetime abuse: 31% sexual abuse, 43% physical abuse, and 49% any abuse. As shown in Table 1, women were significantly more likely to report sexual abuse (51% vs. 14%) and physical abuse (59% vs. 31%). Overall, 28% of participants met diagnostic criteria for lifetime PTSD. Women were significantly more likely than men to have PTSD (42% vs. 17%). The index traumas for PTSD were 46% sexual abuse, 35% physical abuse, 35% death, 12% witness to trauma, and 27% other (e.g., motor vehicle accident, natural disaster). Participants who reported lifetime abuse were more likely to have PTSD (39% vs. 18%, χ2(1) = 4.79, p = .03).

Table 1.

Gender differences in lifetime sexual/physical abuse and PTSD

| Women (n = 41) | Men (n = 49) | χ 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual abuse | 51.2% | 14.3% | 14.21*** |

| Physical abuse | 58.5% | 30.6% | 7.09** |

| Sexual and/or physical abuse | 68.3% | 32.7% | 11.35** |

| PTSD | 41.5% | 16.7% | 6.73* |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

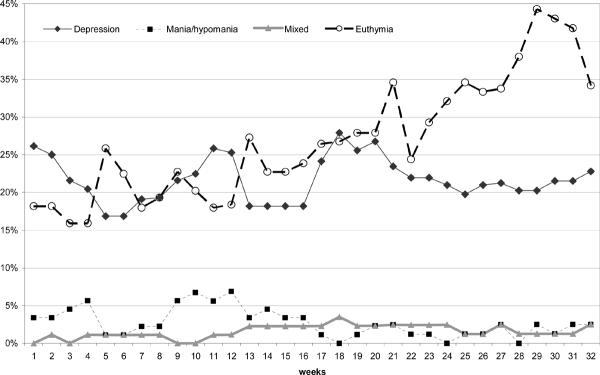

Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of participants who met criteria for depression, mania/hypomania, mixed mania, and euthymia each week over the 32-week assessment period. Over time, the proportion of participants experiencing depression, mania/hypomania, and mixed mania on any given week remained relatively stable, while the proportion of participants experiencing euthymia steadily increased. Table 2 describes the proportion of participants who experienced at least 1 week in each mood state, as well as the mean, median, and range of weeks they were in each mood state. Most participants had at least 1 week of depression (73%) and euthymia (72%), while mania/hypomania (44%) and mixed mania (12%) were less common. Participants experienced more weeks of depression (6.6 ± 7.1, median = 4) and euthymia (8.0 ± 8.3, median = 7) than mania/hypomania (1.8 ± 3.0, median = 0) or mixed mania (0.5 ± 2.0, median = 0). Table 2 also describes the proportion of participants who had any mood recurrences and any polarity shifts, as well as the mean, median, and range of each. Most participants (72%) had at least one mood recurrence, with recurrences to depression occurring more frequently than recurrences to mania (56% vs. 41%). Approximately half of participants (52%) had a least one polarity shift, with indirect shifts occurring more frequently than direct shifts (46% vs. 14%).

Figure 1.

Week-by-week proportion of participants meeting syndromal criteria for each mood state

Table 2.

Description of mood outcomes over the 32-week assessment period

| Proportion reporting any | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of weeks in mood state | ||||

| Depression | 73% | 6.6 (7.1) | 4 | 0–32 |

| Mania/hypomania | 44% | 1.8 (3.0) | 0 | 0–12 |

| Mixed mania | 12% | 0.5 (2.0) | 0 | 0–13 |

| Euthymia | 72% | 8.0 (8.3) | 7 | 0–31 |

| Number of mood recurrences | ||||

| Any | 72% | 1.4 (1.4) | 1 | 0–7 |

| Depression | 56% | 0.8 (0.8) | 1 | 0–3 |

| Mania/hypomania/mixed | 41% | 0.7 (1.0) | 0 | 0–5 |

| Number of polarity shifts | ||||

| Any | 52% | 0.9 (1.5) | 0 | 0–10 |

| Direct | 14% | 0.3 (1.0) | 0 | 0–7 |

| Indirect | 46% | 0.6 (0.9) | 0 | 0–5 |

Table 3 shows the results of the negative binomial regression models predicting number of weeks in each mood state. In the univariate analyses, gender, lifetime abuse, and PTSD were significant predictors of mixed mania and euthymia. Specifically, for women compared to men, the rate of mixed mania was over eight times higher, and the rate of euthymia was almost half. For participants with lifetime abuse, the rate of mixed mania was over ten times higher, and the rate of euthymia was almost half. For participants with PTSD, the rate of mixed mania was over seven times higher, and the rate of euthymia was almost half. In multivariable analysis predicting weeks of mixed mania, only lifetime abuse and PTSD remained significant predictors. Specifically, the rate of mixed mania was over four times higher for participants with lifetime abuse, and it was also over four times higher for participants with PTSD. After accounting for lifetime abuse and PTSD, the effect of gender on mixed mania was reduced by 64% (RR = 8.53 vs. 3.03). Results of the bootstrap analysis comparing the adjusted and unadjusted effects of gender suggest that the relationship between gender and mixed mania was partially explained by lifetime abuse (ab = 0.15 (0.03 – 0.48), p < .05) but not PTSD (ab = 0.25 (0.02 – 1.01), p > .05). In the multivariable analysis predicting euthymia, only lifetime abuse remained a significant predictor. Specifically, the rate of euthymia was almost half for participants with lifetime abuse. After accounting for the effects of lifetime abuse and PTSD, the effect of gender increased by 31% (RR = 0.58 vs. 0.76). Results of the bootstrap analysis suggest that the effect of gender on euthymia was not explained by lifetime abuse (ab = −0.97 (−2.88 - −0.04), p > .05).

Table 3.

Negative binomial regression models predicting weeks in each mood state, relative rate (95% confidence interval)

| Depression | Mania/hypomania | Mixed mania | Euthymia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate models | ||||

| Female gender | 1.21 (0.76 – 1.91) | 1.65 (0.97 – 2.80) | 8.53 (3.09 – 23.59)*** | 0.58 (0.36 – 0.92)* |

| Lifetime abuse | 1.25 (0.78 – 1.99) | 1.67 (0.87 – 2.83) | 10.49 (3.29 – 33.45)*** | 0.51 (0.33 – 0.80)** |

| PTSD | 1.03 (0.63 – 1.69) | 0.95 (0.52 – 1.71) | 7.30 (3.01 – 17.69)*** | 0.59 (0.35 – 0.99)* |

| Multivariable model | ||||

| Female gender | 1.18 (0.71 – 1.95) | 1.05 (0.88 – 2.89) | 3.03 (0.94 – 9.81) | 0.76 (0.45 – 1.29) |

| Lifetime abuse | 1.24 (0.73 – 2.11) | 1.57 (0.88 – 2.79) | 4.74 (1.29 – 17.43)* | 0.58 (0.36 – 0.94)* |

| PTSD | 0.88 (0.50 – 1.55) | 0.66 (0.34 – 1.29) | 4.32 (1.65 – 11.34)** | 0.74 (0.42 – 1.29) |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 4 shows analogous results of the negative binomial regression models predicting number of mood recurrences and number of polarity shifts. In the univariate analyses, for women compared to men, the rate of recurrences to mania was nearly twice as high, and the rate of direct polarity shifts was nearly four times higher. Lifetime abuse and PTSD were unrelated to recurrences to mania, but they were predictive of more direct polarity shits. Specifically, the rate of direct polarity shifts were over six times higher for participants with lifetime abuse and over twice as high for those with PTSD. In the multivariable analysis predicting direct polarity shifts, only lifetime abuse remained a significant predictor, with the rate of direct polarity shifts being over four times higher for participants with lifetime abuse. After accounting for lifetime abuse and PTSD, the effect of gender was reduced by 42% (RR = 3.71 vs. 2.14). Results of the bootstrap analysis comparing the adjusted and unadjusted effects of gender suggest that the relationship between gender and direct polarity shifts was partially explained by lifetime abuse (ab = .11 (.03 – 0.30), p < .05).

Table 4.

Negative binomial regression models predicting mood recurrences and polarity shifts, relative rate (95% confidence interval)

| Recurrences to | Polarity shifts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Any mania | Direct | Indirect | |

| Univariate models | ||||

| Female gender | 1.14 (0.60 – 2.17) | 1.96 (1.00 – 3.84)* | 3.71 (1.42 – 9.68)** | 1.49 (0.76 – 2.95) |

| Lifetime abuse | 1.45 (0.76 – 2.78) | 1.50 (0.77 – 2.93) | 6.33 (2.02 – 19.85)** | 2.00 (1.00 – 4.00)* |

| PTSD | 1.23 (0.61 – 2.47) | 1.72 (0.85 – 3.50) | 2.50 (1.00 – 6.20)* | 1.70 (0.83 – 3.48) |

| Multivariable model | ||||

| Female gender | 1.03 (0.52 – 2.05) | 1.68 (0.80 – 3.53) | 2.14 (0.73 – 6.28) | 1.13 (0.53 – 2.39) |

| Lifetime abuse | 1.45 (0.71 – 2.94) | 1.12 (0.53 – 2.34) | 4.40 (1.31 – 14.79)* | 1.74 (0.83 – 3.65) |

| PTSD | 1.08 (0.51 – 2.29) | 1.41 (0.66 – 3.01) | 1.29 (0.46 – 3.62) | 1.37 (0.63 – 3.01) |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Discussion

This sample of patients with co-occurring BD I and SUD reported a high rate of syndromal mood symptoms over the 8-month assessment period. On any given week, 21% had depression, 6% had mania or hypomania, and 2% had mixed mania. Other studies have also found that depression is more common than mania. For example, the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study found that patients were depressed on 44% of days and manic on 21% of days over 2 years (19). Similarly, the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study (CDS) found that BD I participants spent a mean of 9% of weeks in a major depressive episode and 7% of weeks in a manic or hypomanic episode over an average of 14 years (49). Compared to the CDS, our participants reported proportionately more weeks of depression, possibly due to co-occurring SUDs or the shorter assessment period. The proportion of participants who experienced euthymia did increase steadily over time, with 72% reporting at least 1 week of euthymia during the follow-up period. This improvement may be due to a combination of factors, including receipt of mood stabilizer medications, participation in psychosocial group treatment, and enrollment in a longitudinal research study. In sum, these results suggest that BD I patients with co-occurring SUD experience persistent mood symptoms over time, with depression experienced more frequently than mania.

Participants also reported a high rate of mood recurrence and polarity shifts. During the 8-month assessment period, 56% had a recurrence to depression and 41% had a recurrence to mania. Moreover, approximately half of participants had at least one polarity shift, with indirect shifts (depression to no mood state to mania, or vice versa) occurring more frequently than direct shifts (depression to mania, or vice versa). These findings are somewhat consistent with previous reports. For example, the STEP-BD study found that 35% of patients had a recurrence to depression and 14% had a recurrence to mania during the 2-year follow-up (19). In the CDS, participants had a mean of 3.5 polarity shifts per year; however, this included subsyndromal symptoms (49). In the McLean-Harvard First Episode Mania Study, 40% of patients experienced a new episode of mania or depression within 2 years of syndromal recovery, and 19% switched phases without recovery (57).

The mood outcomes examined in this study (i.e., chronicity, mood recurrences, polarity shifts) were chosen because of their association with a less favorable course of BD. Specifically, prior studies have found that disease burden and impairment are predicted by number of weeks in depressed or manic syndromes (35), history of mixed mania (18, 38, 39), and more polarity shifts (12, 35–37). In the current study, women experienced more weeks of mixed mania, fewer weeks of euthymia, more recurrences to mania, and more direct polarity shifts. These results suggest that women may have a less favorable prognosis. Prior explanations for this observation have focused on gender differences in vulnerability to depression, which may place women at increased risk for mixed mania and polarity shifts (14, 58, 59). However, our study found no gender differences in weeks of depression or recurrences to depression. Thus, other factors may help explain observed gender differences.

In this sample of patients with co-occurring BD I and SUD, the effect of gender on mood outcomes was attenuated after accounting for lifetime sexual/physical abuse and PTSD diagnosis. In the multivariable models, lifetime abuse was predictive of more mixed mania, less euthymia, and more direct polarity shifts. Moreover, lifetime abuse partially explained the relationship between gender and weeks of mixed mania, as well as the relationship between gender and direct polarity shifts. It could be that symptoms of trauma-related stress (e.g., hyperarousal, insomnia, recurrent memories, anger) interact with symptoms of BD, contributing to increased mood lability. For example, environmental cues associated with prior abuse may trigger flashbacks, panic attacks, or anger outbursts. Depression, sleep disturbance, irritability, and restlessness are also common in individuals with abuse histories (60). It has been suggested that early trauma is associated with exaggerated cycles of highs and lows that contribute to mood instability over time by permanently changing brain physiology (61, 62). It is important to note, however, that the effect of lifetime abuse on mixed mania, euthymia, and direct polarity shifts remained significant after accounting for PTSD. This suggests that our findings cannot be explained by overlapping symptoms in BD and PTSD. These results underscore the importance of assessing abuse history in BD patients and recognizing its potential relationship to mixed mania and polarity shifts.

After accounting for gender and lifetime abuse, PTSD was predictive of more mixed mania, but not euthymia or direct polarity shifts. Moreover, PTSD did not explain the relationship between gender and mixed mania. PTSD is characterized by frequent re-experiencing of the traumatic event, avoidance of triggers, and hyperarousal. In the context of mood episodes, these generally arousing symptoms may contribute to a mixed manic presentation. Future research might examine the independence and overlap of BD and PTSD symptoms in patients with these co-occurring disorders.

This study had a number of strengths, most notably the prospective design used to examine the course of BD I in dually diagnosed patients over time. To reduce recall bias, assessments occurred monthly, and participants provided detailed, weekly accounts of their mood symptoms using validated methods. Participants completed both self-report questionnaires and clinical interviews with multiple assessors (research assistants and clinicians). Thus, this study provides an in-depth view of mood symptoms over time, albeit over a relatively shorter assessment period. Nevertheless, results should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, participants were primarily White and well-educated, and all were volunteers in a multi-session group treatment study. The sample may therefore not be representative of all patients with co-occurring BD and SUD. For example, they may have been motivated by more severe symptoms to seek additional services. Second, the purpose of this study was to examine the longitudinal course of BD I in patients with co-occurring SUD. Therefore, results may not generalize to the broader population of BD I patients. Third, the ASI, while well-validated in substance abusing samples, is not specific to trauma-related issues and does not assess severity of abuse. It is also a self-report measure and some cases of abuse may have been missed. Finally, factors not examined in the current study may have contributed to the results; the validity of the estimates of the effects from the regression analyses relies on the assumption of no unmeasured confounders. Additional research is thus necessary to replicate these findings with larger and more diverse samples of BD patients with and without co-occurring SUD.

In sum, this study is consistent with prior reports describing gender differences in the prevalence of mixed mania and rapid cycling in BD I patients. However, our findings suggest that a history of physical or sexual abuse may partially explain the relationship between gender and these mood outcomes, at least in patients with co-occurring SUD. That is, women are more likely to experience a history of abuse, which in turn is associated with increased mixed mania and polarity shifts. These results underscore the importance of assessing abuse histories in BD patients. Further research is needed to better understand the link between stressful life experiences, neurobiological development, and psychopathology; this could help us better address histories of abuse in the treatment of patients with BD and SUD.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by grants R01DA15968, T32DA01536, and K24DA022288 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

References

- 1.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou P, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and Axis I and II disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1205–15. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiskal HS, Hantouche EG, Bourgeois ML, Azorin J-M, Sechter D, Allilaire J-F, et al. Gender, temperament, and the clinical picture in dysphoric mixed mania: findings from a French national study (EPIMAN) J Affect Disord. 1998;50:175–86. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Jr, Tugrul KL, West SA, Lonczak HS. Differences and similarities in mixed and pure mania. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36:187–94. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(95)90080-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Micheli C, Musetti L, Paiano A, Quilici C, et al. Clinical subtypes of bipolar mixed states: validating a broader European definition in 143 cases. J Affect Disord. 1997;43:169–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)01446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassidy F, Ahearn EP, Carroll BJ. Substance abuse in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suppes T, Mintz J, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Kupka RW, Frye MA, et al. Mixed hypomania in 908 patients with bipolar disorder evaluated prospectively in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Network. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1089–96. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldassano CF, Marangell LB, Gyulai L, Nassir Ghaemi S, Joffe H, Kim DR, et al. Gender differences in bipolar disorder: retrospective data from the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:465–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendrick V, Altshuler LL, Gitlin MJ, Delrahim S, Hammen C. Gender and bipolar illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:393–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunner DL, Patrick V, Fieve RR. Rapid cycling manic depressive patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1977;18:561–6. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nurnberger J, Jr., Guroff JJ, Hamovit J, Berrettini W, Gershon E. A family study of rapid-cycling bipolar illness. J Affect Disord. 1988;15:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lish JD, Gyulai L, Resnick SM, Kirtland A, Amsterdam JD, Whybrow PC, et al. A family history study of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1993;48:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(93)90111-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, Calabrese JR, Allen MH, Thomas MR, Wisniewski SR, et al. Phenomenology of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1902–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, Suppes T, Altshuler LL, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Comparison of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disorder based on prospective mood ratings in 539 outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1273–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coryell W, Endicott J, Keller M. Rapidly cycling affective disorder. Demographics, diagnosis, family history, and course. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:126–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820020046006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, Greenberg PE, Hirschfeld RM, Petukhova M, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frye MA, Altshuler LL, McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Denicoff K, et al. Gender differences in prevalence, risk, and clinical correlates of alcoholism comorbidity in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:883–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDermott BE, Quanbeck CD, Frye MA. Comorbid substance use disorder in women with bipolar disorder associated with criminal arrest. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:536–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.González-Pinto A, Aldama A, Mosquera F, González Gómez C. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of mixed mania. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:611–26. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, Marangell LB, Zhang H, Wisniewski SR, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: Primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217–24. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strakowski SM, Keck PE, McElroy SL, West SA, Sax KW, Hawkins JM, et al. Twelve-month outcome after a first hospitalization for affective psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briere J, Elliot DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. 2003;27:1205–22. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott DM, Mok DS, Briere J. Adult sexual assault: Prevalence, symptomatology, and sex differences in the general population. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:203–11. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000029263.11104.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. U.S. Department of Justice; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown GR, McBride L, Bauer MS, Williford WO. Impact of childhood abuse on the course of bipolar disorder: A replication study in U.S. veterans. J Affect Disord. 2005;89:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg JF, Garno JL. Development of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult bipolar patients with histories of severe childhood abuse. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitan RD, Parikh SV, Lesage AD, Hegadoren KM, Adams M, Kennedy SH, et al. Major depression in individuals with a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse: Relationship to neurovegetative features, mania, and gender. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1746–52. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, et al. Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:288–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leverich GS, Post RM. Course of bipolar illness after history of childhood trauma. Lancet. 2006;367:1040–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68450-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolodziej ME, Griffin ML, Najavits LM, Otto MW, Greenfield SF, Weiss RD. Anxiety disorders among patients with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levander E, Frye MA, McElroy S, Suppes T, Grunze H, Nolen WA, et al. Alcoholism and anxiety in bipolar illness: Differential lifetime anxiety comorbidity in bipolar I women with and without alcoholism. 2007;101:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thatcher JW, Marchand WR, Thatcher GW, Jacobs A, Jensen C. Clinical characteristics and health service use of veterans with comorbid bipolar disorder and PTSD. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:703–7. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: Data From the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mysels DJ, Endicott J, Nee J, Maser JD, Solomon D, Coryell W, et al. The association between course of illness and subsequent morbidity in bipolar I disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Bartoli L. The prognostic significance of “switching” in patients with bipolar disorder: A 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1711–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turvey CL, Coryell WH, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Endicott J, Keller MB, et al. Long-term prognosis of bipolar I disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:110–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb07208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Post RM, Rubinow DR, Uhde TW, Roy-Byrne PP, Linnoila M, Rosoff A, et al. Dysphoric mania: Clinical and biological correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:353–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810040059009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Coryell W, Endicott J, Mueller TI. Bipolar I: A five-year prospective follow-up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:238–45. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss R, Griffin M, Kolodziej M, Greenfield S, Najavits L, Daley D, et al. A randomized trial of integrated group therapy versus group drug counseling for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:100–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Jaffee WB, Bender RE, Graff FS, Gallop RJ, editors. Integrated group therapy for patients with bipolar disorder and substance dependence can be successfully delivered by drug counselors. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: May 3–8, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.APA . Text Revision. Fourth Edition American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daley DC, Mercer D, Carpenter G. Group Drug Counseling for Cocaine Dependence. USDHHS; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient/Non-patient Edition, (SCID-I/P) or (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, et al. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, et al. A prospective 12-year study of subsyndromal and syndromal depressive symptoms in unipolar major depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:694–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLellan A, Luborsky L, Woody G. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sobell L, Sobell M. TimeLine Follow Back: A Calendar Method for Assessing Alcohol and Drug Use. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto, Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hilbe JM. Negative Binomial Regression. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; Boca Raton, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mooney CZ, Duval RD. Bootstrapping: A Nonparametric Approach to Statistical Inference. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36:717–31. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tohen M, Zarate CA, Jr., Hennen J, Khalsa HM, Strakowski SM, Gebre-Medhin P, et al. The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: Prediction of recovery and first recurrence. 2003;160:2099–107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weissman MM, Klerman GL. The chronic depressive in the community: unrecognized and poorly treated. Compr Psychiatry. 1977;18:523–32. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(97)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic Depressive Illness. Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zlotnick C, Shea MT, Begin A, Pearlstein T, Simpson E, Costello E. The validaton of the Trauma Symptom Checklist-40 (TSC-40) in a sample of inpatients. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:503–10. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Post RM. Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. 1992;149:999–1010. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.8.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Kolk BA. The psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]