Summary

It has been well established that a single amino acid sequence can give rise to several conformationally distinct amyloid states. The extent to which amyloid structures formed within the same sequence are different, however, remains unclear. To address this question we studied two amyloid states (referred to as R- and S-fibrils) produced in vitro from highly purified full-length recombinant prion protein (PrP). Several biophysical techniques including X-ray diffraction, CD, FTIR, hydrogen-deuterium exchange, proteinase K-digestion, and binding of a conformation-sensitive fluorescence dye revealed that R- and S-fibrils have substantially different secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures. While both states displayed a 4.8 Å meridional X-ray diffraction typical for amyloid cross-β spines, they showed markedly different equatorial profiles suggesting different folding pattern of β-strands. The experiments on hydrogen-deuterium exchange monitored by FTIR revealed that only small fractions of amide protons were protected in R- or S-fibrils, an argument for the dynamic nature of their cross-β structure. Despite this fact, both amyloid states were found to be very stable conformationally as judged from temperature-induced denaturation monitored by FTIR and the conformation-sensitive dye. Upon heating to 80 °C, only local unfolding was revealed, while individual state-specific cross-β features were preserved. The current studies demonstrated that the two amyloid states formed by the same amino acid sequence exhibited significantly different folding patterns that presumably reflect two different architectures of cross-β structure. Both S- and R-fibrils, however, shared high conformational stability arguing that the energy landscape for protein folding and aggregation can contain several deep free energy minima.

Keywords: amyloid fibrils, prion protein, X-ray diffraction, FTIR, hydrogen-deuterium exchange

Introduction

It has been well established that conformationally different amyloid states can be produced by the same amino acid sequence 1-5. The principle underlying the ability of a protein to acquire multiple self-propagating structures was first introduced by the protein-only hypothesis of prion propagation to explain formation of multiple prion strains within the same host 6. While in the past this principle was considered to be limited to the mammalian prion protein, the ability of the same sequence to give rise to different self-propagating states has now been well demonstrated for several yeast prion proteins and a number of disease-related or disease non-related polypeptides 1, 3-5, 7-9.

The extent to which amyloid structures formed by the same sequence are different, however, is currently unclear. It is not known whether the state-specific variations in amyloid structures originate from fundamentally different global folds or only from minor variations within the same folding and assembly pattern. This question has numerous implications for our understanding of the origin of prion strains, the range of their biological activities, the conformational diversity of functional and pathological amyloids, and the mechanisms for protein-encoded inheritance.

To date, the mechanisms underlying the conformational differences in amyloid fibrils have been largely explored using relatively short peptides 5, 10, 11. In recent studies, packing polymorphism (i.e. alternative packing arrangements of β-sheets formed by the same segment of a protein) and segmental polymorphism (i.e. different segments of a protein form β-sheets) were found to contribute to the structural diversity in amyloid fibrils formed by several hexapeptides 5. Variations in symmetry of lateral interactions between protofilaments offer an additional source for structural polymorphism in amyloid fibrils 10, 12. Two amyloid states produced from Aβ(1-40) peptide were shown to consist of nearly identical β-strand segments that acquired either twofold and threefold symmetries when assembled into mature fibrils 10.

Due to a number of technical difficulties, few studies have been undertaken to elucidate state-specific differences in amyloid fibrils produced by large polypeptides such as full-length prion protein. Because structural approaches are often limited to imaging techniques such as electron microscopy or atomic force microscopy, fibril morphology has been identified as one of the major tools for assessing structural polymorphism 13-15. In addressing the question of state-specific structural differences it is important to make a distinction between actual conformational polymorphisms that arise from different structures of cross β-spines and morphological polymorphisms that might occur solely as a result of alternative modes of lateral assembly of filaments. In previous studies, we showed that fibrils produced from the full-length recombinant prion protein (PrP) under a single set of growth conditions were highly polymorphous and that this polymorphism arises due to variations in the number of protofilaments and alternative modes of lateral assembly of protofilaments into mature fibrils 16, 17. Despite significant morphological polymorphism, however, the structure of the cross β-spine appeared to be uniform in these fibrils as judged from FTIR 2 and hydrogen-deuterium exchange Raman spectroscopy (Baskakov, Lednev, unpublished observation). Surprisingly, prion strains isolated from scrapie brains were shown to display overlapping fibril morphologies 18, 19. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that polymorphysm in fibril morphology does not directly report on state-specific or strain-specific cross-β spine structures.

To test the extent to which amyloid states formed within the same primary structure are different, we used two types of amyloid fibrils (referred to as R- and S-fibrils) produced from highly purified full-length recombinant PrP 2. Several biophysical techniques including X-ray diffraction, CD, FTIR, hydrogen-deuterium exchange, proteinase K (PK) digestion and binding of conformation-sensitive fluorescence dye revealed that two amyloid states exhibit significantly different folding patterns within their cross-β sheet structure. X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed cross-β structure for both states, but revealed radically different equatorial patterns. Remarkably, despite fundamental differences in global structures, both S- and R-fibrils were highly stable thermodynamically. Contrary to the commonly accepted view, this work suggests that the energy landscape for protein folding and assembly contains several global free energy minima: one of which is occupied by a native state and more than one being occupied by amyloid states.

Results

Previously we showed that two amyloid states referred to as R and S could be produced from full-length recombinant hamster PrP under two different agitation modes 2. R- and S-fibrils displayed very distinctive morphologies as judged by EM and AFM (Suppl. Fig. 1). Considering that R- and S-fibrils were formed under identical solvent conditions from the same stock solution of PrP, we were interested in determining the extent to which their structures were different.

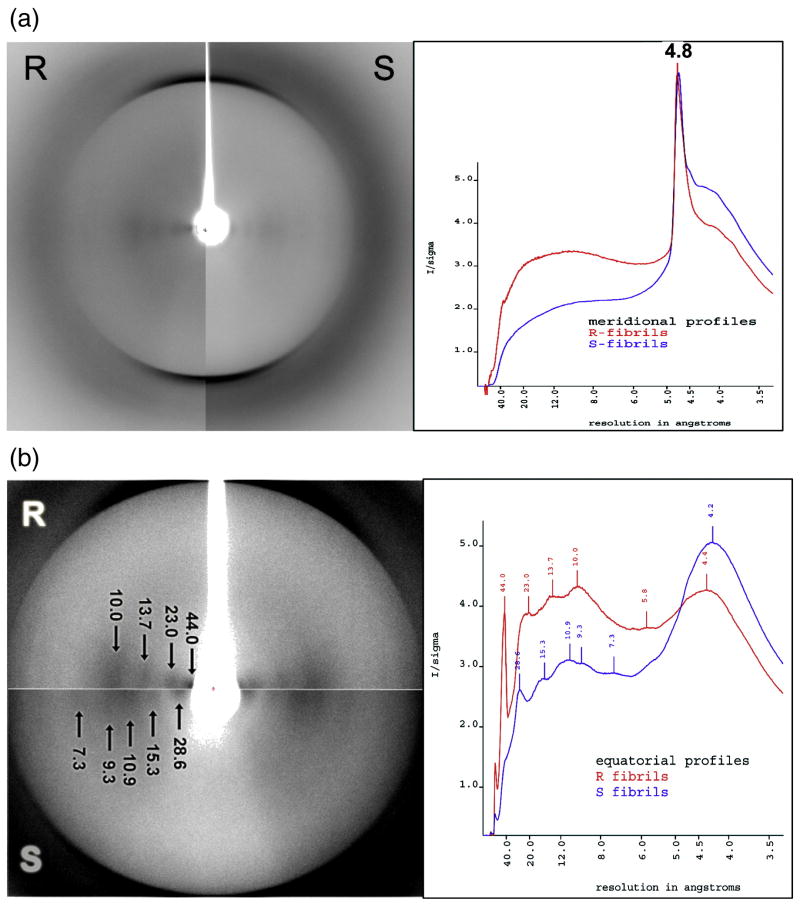

X-ray diffraction reports different folding patterns within cross-β structures of R- and S-fibrils

Confirming that both states consist of cross-β structure, X-ray diffraction analysis revealed a single major meridional reflection at 4.8 Å and equatorial reflections near 10 Å in both R- and S- fibrils (Fig.1a). However, the two diffraction patterns were not identical; due to the relatively high degree of order in these fibrils, differences in the pattern of equatorial reflections were observed (Fig. 1b). The equatorial diffraction from R-fibrils showed 10, 13.7, 23 and 44 Å bands, whereas S-fibrils displayed 7.3, 9.3, 10.9, 15.3 and 28.6 Å bands. These data suggest that the PrP molecules have distinct folding and assembly patterns within R- and S-fibril.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction of R- and S-fibrils. (a) Broad-range diffraction pattern displays a single 4.8 Å band in meridional profiles (vertical dissection) for both amyloid states. (b) Horizontal dissection (equatorial profile) of high-range diffraction pattern reveals distinctive sets of bands for R- and S- fibrils.

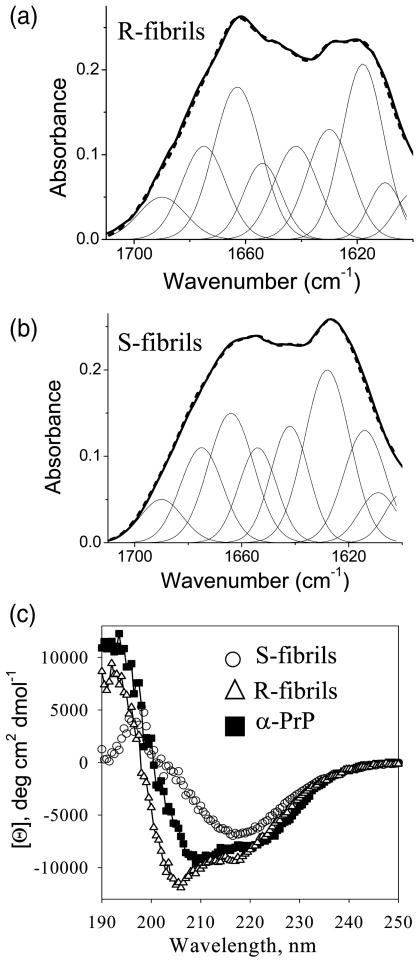

R- and S-fibrils show substantial differences in their secondary structure

To estimate the secondary structure content, the infrared spectra of R- and S-fibrils were fitted using a combination of gaussian peaks with maxima taken from second derivatives of FTIR spectra (Fig. 2a,b). In our previous work, two FTIR bands corresponding to beta-sheet structures were found for both R- and S- fibrils 2. While the β-sheet component was predominant in both fibrillar types, the position and the ratio of two subcomponents were different in two amyloid states (Table 1). The subcomponents designated as CB-1 displayed maxima at 1630 cm-1 and 1628 cm-1 for R- and S-fibrils, respectively, and the subcomponent CB-2 peaked at 1618 cm-1 and 1614 cm-1 for R- and S-fibrils, respectively. The peak at 1663 cm-1 which is often assigned to turn conformations 20 was more substantial in R- than in S-fibrils suggesting that R-structure includes more β- or γ-turns. The percentage of unordered structure was the same in R- and S-fibrils (Table 1). In deconvoluting the FTIR spectra it is important to keep in mind that due to uncertainty in width of the bands assigned to different elements of secondary structure, the estimation of secondary structure content is a subject to large errors.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the secondary structure of R- and S- fibrils. The FTIR spectra (bold lines) and the results of curve fitting (dashed lines) of the FTIR amide I′ region of R-fibrils (a) and S-fibrils (b). Peaks corresponding to individual components of secondary structure are shown by thin lines. (c) Far-UV CD spectra of S-fibrils (○), R-fibrils (△), and monomeric α-PrP (■).

Table 1.

Secondary structure composition as determined from deconvolution and curve fitting of the FTIR amide I′ band

| Wavenumber cm-1 | % secondary structure a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R-fibrils | S-fibrils | ||

| α-helix | ∼1654 | 9 ± 3 | 11 ± 3 |

| Cross-β sheet | CB-1b | 16 ± 1 | 26 ± 2 |

| CB-2c | 28.5 ± 1.5 | 14.0 ± 1.5 | |

| turn conformations | ∼1663 | 21 ± 2 | 15 ± 1 |

| ∼1675 | 11 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | |

| ∼1690 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | |

| random coil | ∼1642 | 13 ± 1 | 14 ± 0.8 |

Mean values ± standard deviation for three independent preparations of PrP firbils

CB-1 band corresponds to 1630 cm-1 or 1628 cm-1 for R- or S-fibrils, respectively.

CB-2 band corresponds to 1618 cm-1 or 1614 cm-1 for R- or S-fibrils, respectively.

CD spectroscopy confirmed significant differences in secondary structures between R- and S-fibrils. S-fibrils showed spectra typical for β-sheet-rich proteins, whereas R-fibrils exhibited a substantial negative peak at 205 nm (Fig. 1c) that could be assigned to type I β-turns 21 and/or superhelical twists which are typical for R-fibril morphology (Suppl. Fig. 1). The latter explanation was supported by a decrease in the amplitude of the 205 nm peak that was observed upon intensive fragmentation of R-fibrils using sonication (Suppl. Fig. 2a). Therefore, the negative peak at 205 was attributed, in part, to superhelical twists witnessing left-handed helicity in R-fibrils. Nevertheless, even after sonication significant differences remained between CD spectra of R- and S- fibrils. Both, CD and FTIR spectroscopy revealed a substantially larger contribution of turn conformations in R-fibrils compared to that in S-fibrils.

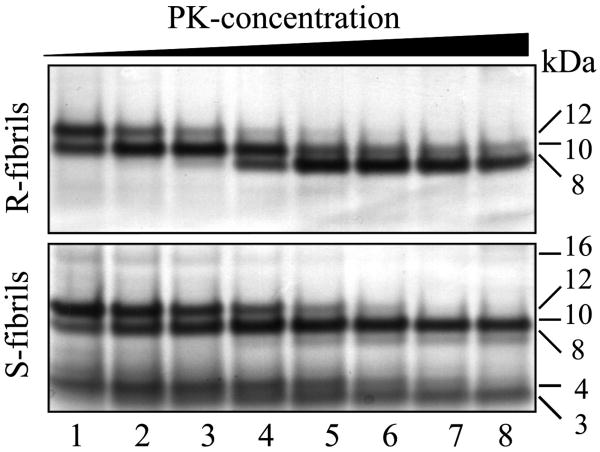

N-terminal region is PK-resistant in S-fibrils

To determine whether the same PrP region is involved in forming the most proteolytically resistant cross-β spine in two amyloid states, we employed a PK-digestion assay. PK digestion followed by SDS-PAGE revealed a triplet of bands with molecular weights of 8, 10 and 12 kDa in both fibrillar types (Fig. 3). The relative intensity of bands, however, was markedly different for R- and S-fibrils. Upon increased PK concentration, R-fibrils showed a progressing reduction in the size of the PK-resistant spine from 12 kDa to 10 kDa and finally to 8 kDa, whereas S-fibrils displayed a very stable spine of 10 kDa even at high PK concentrations. Furthermore, additional PK-resistant bands with apparent molecular weights of ∼ 4 and 3 kDa were present in the digestion assays of S-fibrils. The 3 kDa band was as stable toward PK as the 10 kDa band. Amino acid sequencing by Edman revealed that the small PK-resistant products correspond to the very N-terminus of full-length PrP 23-231 starting from residue 23. Consistent with the sequencing results, none of the antibodies to the central or C-terminal PrP regions (to the epitopes 95-105, 108-111, 132-156, 160-170 or 224-230) were able to detect the short PK-resistant products on Western blotting (data not shown). In addition to the N-terminal peptides, S-fibrils consistently showed a minor 16-kDa band that was detectible only at lower concentrations of PK. The PK digestion assay illustrated that the cross-β spine is likely to have different folding pattern in the two amyloid states and that an additional region is involved in forming the fibrillar spine in S-fibrils. In S-fibrils, the N-terminal region was as stable to PK digestion as the C-terminal regions, illustrating that both regions are equally involved in forming the fibrillar spine.

Figure 3.

PK digestion assay of R-fibrils (top panel) and S-fibrils (bottom panel). PrP fibrils (100 μg/ml) were treated with PK for 1 h at 37 °C at the following concentrations (μg/ml): 0.2 (lane 1), 0.5 (lane 2), 1 (lane 3), 2 (lane 4), 5 (lane 5), 10 (lane 6), 20 (lane 7), and 50 (lane 8) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining. For R-fibrils, only three PK-resistant products of 12, 10 and 8 kDa, starting from the residues 138, 152 and 162, respectively, were found 43, whereas S-fibrils showed additional PK-resistant products at 3 and 4 kDa.

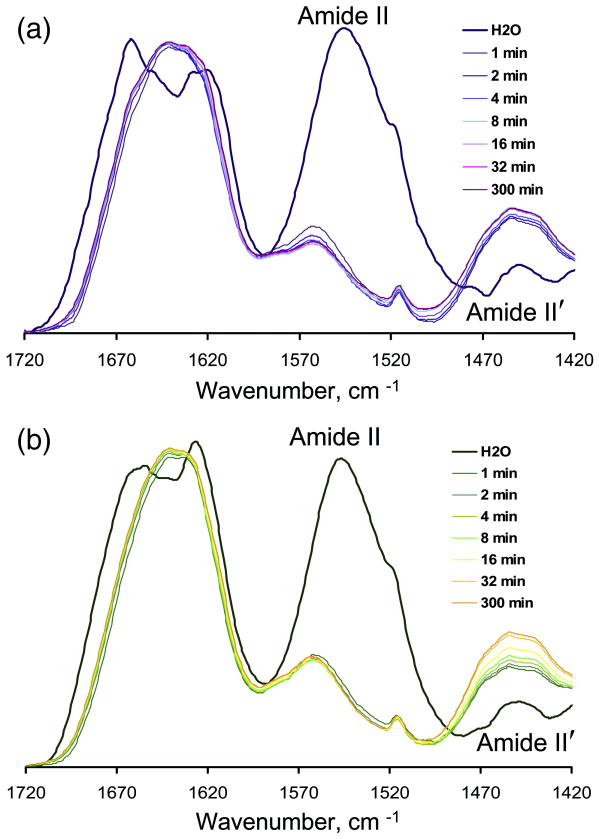

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange showed higher amide protection in R- than in S-fibrils

A transition from the monomeric to the fibrillar state is known to result in a significant increase in amide protection, a process that can be assessed by hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange combined with FTIR. To compare the level of amide protection in S- and R-fibrils, we employed two formats for H/D experiments: (i) PrP samples were dried and then dissolved in D2O water prior to measurements (“dried samples”), or (ii) PrP samples were concentrated in H2O and then diluted with D2O (“wet samples”). The H/D exchange rate was monitored by a shift of Amide II to Amide II′ region in FTIR spectra (Fig. 4). Both types of fibrils showed very fast H/D exchange as judged by the disappearance of the Amide II peak within the first few minutes of experiment (Fig. 4a,b). R-fibrils, however, consistently showed a higher level of amide protection than S-fibrils in both experimental formats, as judged at the end time-point of the experiment (5 hours of exchange) (Table 2). For instance, in “dried samples”, R-fibrils displayed 24-28% protected amides, whereas only 14-20% of amides were protected in S-fibrils. For a set of globular proteins, the level of protection varied from 6.7% for α-PrP to 13.5% for carbonic anhydrase (β-sheet rich protein) reflecting the differences in secondary structure and in a fraction of intrinsically disordered regions between different proteins. In “wet samples”, the level of amide protection was even less than those in “dried samples” for all three PrP isoforms (α-PrP, S- and R-fibrils) (Table 2). Aggregation of fibrils upon drying could account for higher values of amide protection in dried samples than in wet samples.

Figure 4.

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange of amide hydrogens in R-fibrils (a) and S-fibrils (b) as monitored by FTIR spectroscopy. PrP fibrils were dried using a Speedvac, dissolved in D2O, and FTIR spectra were collected at different time points over the following five hours as indicated. FTIR spectra of fibrils in H2O are shown by dark blue and dark green lines, for R- and S-fibrils, respectively.

Table 2.

Amide hydrogen protection in S-fibrils, R-fibrils and globular proteins

| Conservation of amide hydrogen, % * | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dried samples | Wet samples | |

| α-PrP (monomer) | 6.7 | 6.5 |

| R-fibrils | 28.4 | 14.1 |

| 26.8 | 13.8 | |

| 24.1 | 16.2 | |

| S-fibrils | 14.8 | 9.4 |

| 17.6 | 8.2 | |

| 19.9 | 8.7 | |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | 6.9 | n/a |

| Bovine serum albumin | 8.8 | n/a |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 13.5 | n/a |

Percent of amide hydrogens that remained protected after five hours of H/D exchange

After replacing H2O with D2O, Amide I′ regions of the FTIR spectra showed immediate changes (Fig. 4). As judged from CD spectra, however, no alterations in secondary structures of R- or S- fibrils were observed upon replacing H2O with D2O (Suppl. Fig. 2b) arguing that the changes in FTIR spectra are attributable to the change of solvent.

Luminescent-conjugated polythiophene PTAA distinguishes R- and S-fibrils

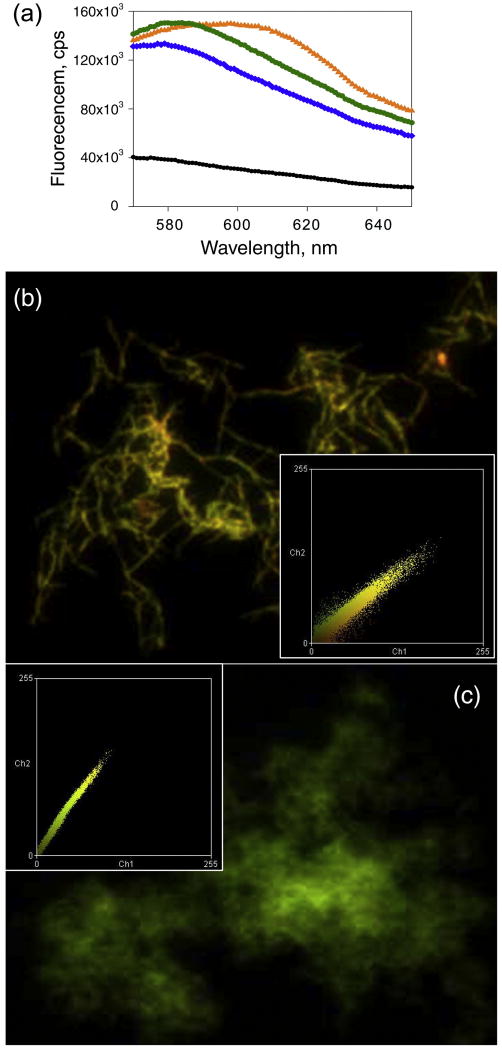

Luminescent-conjugated polythiophenes (LCPs) including poly(thiophene-acetic acid) (PTAA) were previously shown to be effective in detecting conformational differences in amyloid fibrils and prion strains 22,23. In the current study, the S-fibrils displayed a modest shift in the emission spectrum of PTAA relative to the spectrum of α-PrP monomer and showed an emission maximum at 582 nm (Fig. 5a). Binding of PTAA to the R-fibrils, however, caused much more substantial red-shift in the emission maximum than the shift found for the S-fibrils (Fig. 5a). The same effect was observed using fluorescent microscopy where R-fibrils showed a higher ratio of red-to-green emission than the S-fibrils (Fig. 5b,c).

Figure 5.

Influence of R- and S- fibrils on PTAA fluorescence. (a) Fluorescence emission spectra of PTAA alone (black line) and PTAA in the presence of monomeric α-PrP (blue line), S-fibrils (green line) or R-fibrils (orange line) upon excitation at 540 nm. Fluorescence microscopy images of PTAA bound to R-fibrils (b) or to S-fibrils (c). The microscopy images were transformed into two-dimensional fluorescence intensities scattering plots (insets) as previously described 61. Red fluorescence intensities are plotted on the horizontal axis, and the green fluorescence intensities are plotted on vertical axis. All PrP isoforms and PTAA were used at the concentrations 5 μg/ml and 10 μg/ml, respectively, for both fluorescence spectroscopy and microscopy imaging.

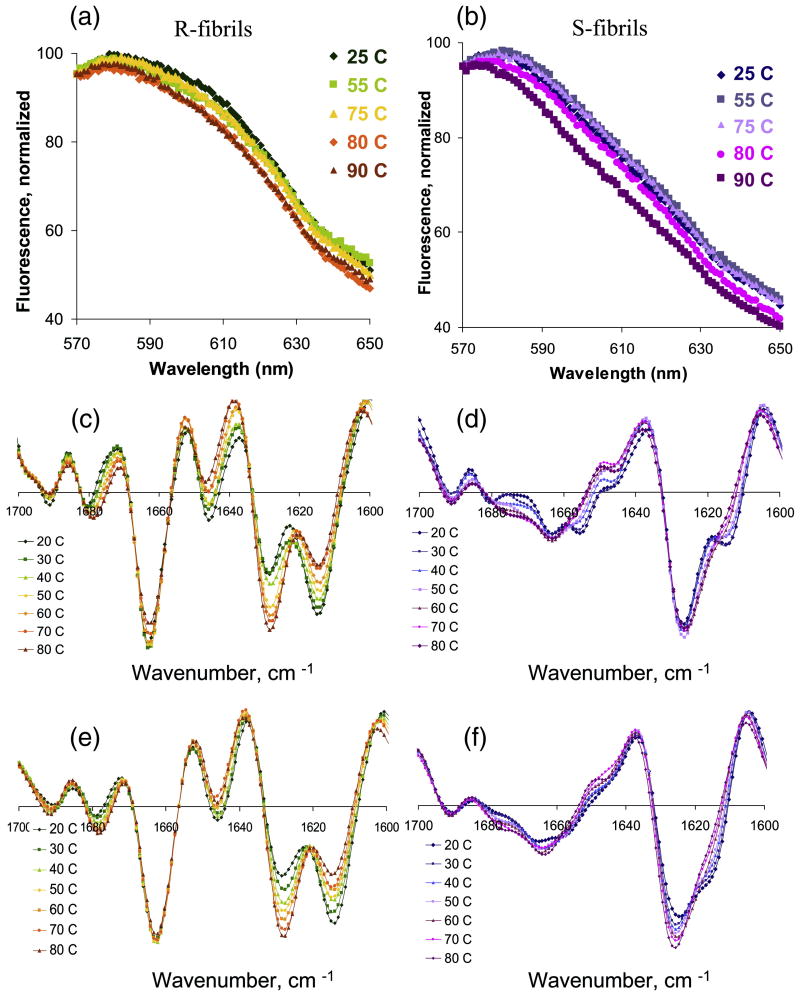

R- and S-fibrils preserve their individual state-specific features under partially denaturing conditions

To provide further insight into the question of whether state-specific conformations arise as a result of different global folding pattern or from the differences in local folds, we were interested in testing whether R- and S-fibrils preserve their individual features upon partial thermal denaturation. Analysis of PTAA fluorescence revealed that both R- and S- fibrils retained their state-specific emission profile upon heating to 80°C and subsequent cooling (Fig. 6a,b). As judged from the second derivatives of FTIR spectra, heating to 80°C caused significant changes in the ratio of CB-1 vs. CB-2 peaks for R-fibrils and almost complete disappearance of the CB-2 subpeak in S-fibrils (Fig. 6c,d). However, even at 80°C, both the R- and S-fibrils preserved their individual FTIR signatures (two comparable peaks CB-1 and CB-2 corresponding to cross β-structure and the peak at 1663 cm-1 in R-fibrils; predominant CB-1 peak for S-fibrils). Remarkably, upon cooling the temperature-induced changes in the secondary structure were completely reversible for R-fibrils and partially reversible for S-fibrils (Fig. 6e,f). These results strongly support the hypothesis that state-specific conformation originates from fundamentally different folding patterns and that both structures are conformationally very stable.

Figure 6.

The R-and S-fibrils were stable to thermal treatment as probed by PTAA fluorescence and FTIR spectroscopy. Fluorescence spectra of PTAA in the presence of R-fibrils (a) or S-fibrils (b). Prior to fluorescence measurements, fibrils were exposed to high temperatures as indicated, cooled down and then mixed with PTAA. Second derivative of FTIR spectra for R-fibrils (c, e) or S-fibrils (d, f) recorded during the time-course of heating from 20 °C to 80 °C (c, d) or cooling from 80 °C to 20 °C (e, f) at 10 deg. C intervals.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that two amyloid states produced in vitro from full-length PrP had significantly different folding and assembly patterns. CD and FTIR spectroscopy revealed significant differences in secondary structure and specifically, that the R-fibrils had substantially more populated turn conformations than the S-fibrils. X-ray diffraction showed that cross-β structures were characterized by clearly different architecture. As judged from the proteolytic digestion, the PK-resistant spine consisted of the N-terminal and C-terminal regions in the S-fibrils but only the C-terminal region in the R-fibrils. The experiment on H/D exchange showed substantial differences between the levels of amide protection for these two fibrillar states. Interaction with a conformationally flexible fluorescent probe revealed striking differences in polypeptide packing. As judged from EM and AFM, R-fibrils consisted of multiple filaments and displayed a straight shape with complex twisted morphologies, whereas the S-fibrils were of a curvy shape and smooth morphology 2. Taken together, our current and previous studies illustrate that R- and S-fibrils were different with respect to their secondary, tertiary and quaternary structures and that the PrP polypeptide chain acquired different global assemblies in these two states.

Amyloid nature of prion fibrils

X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed cross-β structures in both R- and S-fibrils with the meridional profile showing a single reflection at 4.8 Å. On the contrary, equatorial profiles of R- and S-fibrils displayed very distinctive sets of bands (Fig. 1). While lower resolution reflections (corresponding to distances of >15 Å) presumably reflect filament dimensions 24, 25, reflections in the 8-15 Å range are believed to correspond to the distances between β-sheets in the dimensions perpendicular to the fibril axis 26, 27. Notably, the pattern of equatorial reflections from the S-fibrils was very similar to the one reported recently for hamster PrPSc strain Sc237 24. With slight deviation, both profiles contained bands at 7-8, 9.3 and 11 Å. The discrepancy between exact positions could possibly originate from higher order diffraction of a very strong reflection at ∼60 Å in the case of Sc237. While many fibrils produced in vitro from amyloidogenic proteins are characterized by a single thick band at around 10 Å 26, PrP R-fibrils showed two and S-fibrils – four distinctive bands within the same region. Overall, X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that the cross-β spine architecture of PrP fibrils that the folding pattern of PrP molecules within R- and S- fibrils is clearly different.

Structural basis of amyloid states

To be able to propagate individual structures with high fidelity, distinct prion strains have to be thermodynamically and kinetically stable. Such high stability can be achieved if each individual amyloid states occupies a separate deep free energy minima in a free energy landscape and if these minima are separated by large energetic barriers 7. To test this hypothesis, we measured the extent to which amyloid states are stable to thermal denaturation and whether they maintain their individual features during partial denaturation.

The experiments on thermal denaturation revealed that within the range of the tested temperatures (up to 80°C), the S- and R-fibrils were equally stable. As judged from PTAA fluorescence and FTIR spectroscopy, both amyloid states maintained their individual features at the temperatures at which the monomeric α-PrP is known to be fully unfolded 28, 29. Furthermore, no signs of transition from R- to S-structure or vice versa were observed at high temperatures. With few exceptions including globular proteins from extremophiles, only cross-β structures can resist such highly denaturing conditions. Furthermore, the local unfolding observed upon heating up to 80°C was reversible confirming that PrP molecules preserved their individual folds within their amyloid states even under partially denaturing conditions. These results strongly support the idea that state-specific features are encoded by different structures of cross-β spines, i.e. originate from distinctive folding and assembly patterns. These results also provide a molecular basis for explaining the high fidelity of replication of R- and S-fibrils, i.e. their ability to maintain their individual structures during replication under unfavorable agitation conditions as was shown in our previous studies 2.

Relationship between PrPSc and PrP fibrils

As judged from FTIR spectroscopy, the conformations of different PrPSc strains isolated from scrapie brains appear to have more common features 30, 31, 32 than the conformations of S- and R-fibrils generated in vitro. It is quite likely that posttranslational modifications with carbohydrates and the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor limit the conformational space occupied by different PrPSc strains in comparison to that of PrP fibrils generated in vitro.

In recent studies, we showed that transmissible form of prion diseases can be induced in wild type animals by inoculating annealed R-fibrils 33. S-fibrils, on other hand, failed to induce the prion disease in wild type animals 33. These results are surprising considering substantial differences in global structures of R-fibrils and PrPSc. The data on infectivity, however, support the previously introduced hypothesis that the R-structure is more promiscuous than the S-structure 34, 35, i.e. it is capable of seeding the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc despite the lack of compatibility between PrPC and the structure of R-fibrils. Taken together, our studies suggest that only partial similarities or overlap in structures of R-fibrils and PrPSc was sufficient for seeding the conversion of PrPC into PrPSc by R-structures.

Insight into cross-β spine of amyloid states

The cross-β spine is a key structural element of amyloid fibrils and as such represent a major target for developing anti-amyloid drugs 36-38. We employed three different approaches including H/D exchange, FTIR spectroscopy combined with temperature denaturation and a PK digestion assay to assess the differences in the β-spines of the two amyloid states of PrP.

While FTIR analysis might not reflect accurately the actual composition of secondary structure, nevertheless, this method is useful for comparing the structures of PrP amyloid states and PrPSc strains that were previously characterized by FTIR 39, 40. In FTIR spectra, both CB-1 and CB-2 bands report on cross-β structure, where the latter is believed to represent more rigid β-sheets than the former. Notably, a similar double peak arising from cross-β structure was found in FTIR spectra of PrPSc strains 31, 32. CB-2 was found to be significantly smaller in S-fibrils than in R-fibrils. Considering that the fraction of β-structure involved in the interfaces between filaments is greater in R- than in S-fibrils, this result suggests that CB-2 corresponds to the β-sheets that form an interface between filaments, whereas solvent-exposed β-sheets produce CB-1. Consistent with this idea, CB-2 was not influenced by H/D exchange but was substantially reduced upon heating when the filaments seem to dissociate apart. The inter-filament backbone-sidechain and/or sidechain-sidechain hydrogen bonds could provide additional rigidity for the CB-2 β-sheets that form the interface between filaments.

As judged from FTIR, the percentage of β-sheet structures in R- and S-states (∼44% and ∼40%, respectively) were very similar to those previously found in the classical, PK-resistant form of PrPSc (∼43%) 39, 40. The length of the PK-resistant spine, however, was substantially smaller in R- and S-fibrils (∼44% and ∼55%, respectively, calculated per full-length PrP taken as 100%) than that in classical PrPSc (∼70%). These results illustrate that (i) there is no direct correlation between the size of PK-resistant regions and the amount of β-structure, and (ii) the PK-resistant regions can include protease-resistant folds other than cross β-sheet structure. Interestingly, exposure of PK-resistant PrPSc to the mild concentrations of denaturants was shown to expose additional cleavage sites at the residues 139, 142, and 154 41, 42. Remarkably, these sites were very similar to the PK-cleavage sites at residues 138/141 and 152/153 in R-fibrils, which when cleaved produce two C-terminal PK-resistant fragments of 10 and 12 kDa 43, 44. While the global folds of PrPSc and in vitro-generated PrP fibrils appear to be different 24, these results suggest that PrPSc and PrP fibrils might share some common elements of secondary structure.

Because amyloid cross-β spines are believed to be intrinsically stable to H/D exchange, this approach has been employed for assessing the size of the fibrillar β-sheet spine 45, 46. In the current study the level of amide protection was found to be quite low for both states of PrP fibrils, approaching the level found in globular proteins. In part, such a low level of amide protection could be attributed to the fact that substantial portions of the polypeptide are not involved in forming cross-β spine in PrP fibrils. However, the level of amide protection appears to be still substantially lower that one would expect considering that the proteolytically resistant regions encompassed ∼44% or ∼55% of residues in R- or S-fibrils, respectively, and that the cross-β-sheet content (by FTIR) was ∼44% or ∼40%, respectively. Therefore, the hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments argue that the PrP cross-β structures are dynamic and capable of exchanging protons at reasonably high rates. In globular proteins, hydrogen exchange can result from various processes such as global or local unfolding or rapid structural fluctuations 47, 48. To explain fast hydrogen exchange and low fraction of amides protected in PrP fibrils, it is tempting to speculate that parts of PrP amyloid cross-β spines might exhibit high propensity to undergo local unfolding or structural fluctuations.

Previous studies on solution NMR spectroscopy of Aβ amyloid demonstrated that the amide hydrogens of the inner β-strands that formed the interface between filaments were nearly 100% protected from exchange, whereas the amides in the outer solvent-exposed β-sheet layer showed only 50-80% protection 49. In the current studies, the amides in R-fibrils showed a significantly higher level of protection than those in S-fibrils (∼15% versus ∼9% in “wet samples”, respectively). The higher protection in R-fibrils was surprising considering that they had a smaller PK-resistant spine. Because of the differences in the fibril morphology and specifically, complex multifilament twisting morphology in R-fibrils, a substantially larger surface area of β-sheets appears to be involved in forming the inter-filament interface in R-fibrils than in S-fibrils. Therefore, the level of amide protection correlates better with the complexity of fibril morphology, i.e. with the fraction of surface area involved in the inter-filament interface than with the size of the PK-resistant spine.

Role of the N-terminal region in prion propagation

Because the unstructured N-terminal region was previously shown to be unessential for converting PrPC into PrPSc 50, 51, this region has frequently been ignored in previous studies. The current work illustrates that the N-terminal region forms part of the PK-resistant spine in S-fibrils and emphasizes the important role of this region for prion conversion. First, our study argues that the disordered N-terminus is capable of direct interaction with the C-terminal domain. This result is consistent with previous work on motif-grafted antibodies that showed high affinity of binding of PrP19-33 peptide to PrPSc 52, 53. Furthermore, our previous study on site-specific fluorescent labeling of PrP variants revealed direct involvement of the N-terminal region in the initial steps of in vitro fibril formation 54. Second, even though the N-terminal region has never been found to be a part of the PK-resistant spine in authentic PrPSc, its involvement in forming a PK-resistant spine in the S- but not R- fibrils supports the idea that the N-terminus plays an active role in determining prion strain diversity. Third, the current studies provide a mechanistic explanation for our previous results that the presence of miniscule amounts of N-terminally truncated PrP polypeptide in a mixture with intact PrP poisons the fibrillation pathway that leads to S-fibrils 28. As a part of the S-fibrillar spine, the N-terminus might be involved in forming an interface essential for elongation of S-fibrils, therefore its deletion might block elongation of S-fibrils.

Conformation-sensitive luminescent conjugated polythiophenes

Two major parameters are believed to control LCP emission spectra upon their binding to the fibrillar surface: planarity and stacking of dye molecules. Twisted LCP chains were found to emit in green (∼530 nm), whereas a planar LCP backbone leads to gradual red-shift in emission spectra 22. Tight stacking of LCPs results in intermolecular energy transfer between LCP molecules causing further red-shift in emission spectra to ∼640 nm. Therefore, LCP emission offers a valuable tool for assessing conformational properties of amyloids.

Significant red-shift in PTAA emission spectra suggests that PTAA molecules are spaced much more tightly upon their binding to R-fibrils than to S-fibrils. The differences in charge distribution on the fibrillar surface could account in part for the differences in the density of PTAA stacking. In contrast to S-fibrils, the R-fibrils seem to expose the N-terminus to solvent, forming a positively charged matrix that favors dense stacking of polyanion PTAA. Considering that other polyanions were found to be crucially involved in formation of authentic PrPSc in vitro 55-57, PTAA could be very useful not only as a probe for detecting prion aggregates in a tissue, but also as a sensitive polyanion-specific structural marker of prion strains.

In recent studies, the process of adaptation of CWD strains in mice was shown to be accompanied by a substantial red-shift in PTAA emission spectra upon its binding to PrPSc plaques 22. We have previously suggested that the cross-species transmission of prions to new hosts should lead to an increase in conformational promiscuity of prion strains, i.e. an increase in their ability to recruit heterologous PrPC molecules and/or expand the range of compatible heterologous PrPC variants 34, 35. It would be interesting to determine in future studies whether the LCPs can be used as probes for conformational promiscuity of prion strains. The current work revealed that PTAA binding to R-fibrils is accompanied by a substantial red-shift in its emission spectra relative to that of S-fibrils supporting the idea that red-shift in PTAA emissions correlates with the conformational promiscuity of an amyloid state. We previously showed that the R-conformation is highly promiscuous, as it preserves its individual properties within hamster, mouse or even in a mixture of hamster and mouse PrPs 58, whereas the S-conformation is strictly hamster-specific 34.

Materials and Methods

Formation of fibrils from PrP

Recombinant full-length hamster PrP (residues 23-231, no tags) was expressed and purified as previously described 28. To prepare fibrils for structural studies, the fibrillation reactions were conducted in 2M Gdn-HCl, 50 mM MES, pH 6.0 at 37 °C at slow agitation (∼60 rpm) and PrP concentration of 0.25 mg/ml for R-fibrils and at rapid shaking (∼1000 rpm) and PrP concentration of 0.5 mg/ml for S-fibrils. The yield of conversion to fibrillar forms was estimated by SDS-PAGE as previously described 58 and was found to be >95% for each preparation. Identities of fibrils were confirmed by AFM and FTIR for each preparation used in the current study.

X-ray diffraction

The samples of R- or S-fibrils (500 μl of 2 mg/ml in 5 mM sodium acetate) were concentrated by placing them in separate centrifugal concentrators (Centricon-10 kDa molecular weight cutoff) and spun at 5000 rpm for 1 h in a SS34 rotor. The concentrated samples were washed once with 2 ml water and further concentrated to a final volume of 20 μl in a Microcon concentrator (3 kDa molecular weight cutoff). The samples were viscous at this point. After 30 sec of sonication in a water bath, they were diluted with 10 μl water. A volume of 5 μl of each sample was pipetted between the ends of two glass rods. The ends of the glass rods were fire polished and then scratched with fine sand paper. The samples dried at room temperature for 8 h in a closed Petri dish, forming a fiber that stretched between the rods. Diffraction patterns were collected using a Rigaku FR-E X-ray generator with a Cu rotating anode equipped a Rigaku HTC imaging plate detector. The samples were cooled to 100 K. Exposures were collected for 8 min. The crystal-to-film distance was 300 mm. Three independent measurements were performed for each sample.

FTIR spectroscopy, H/D exchange and thermal denaturation

Infrared spectra were measured using Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR instrument (Bruker Optics, Bullerica, MA). Samples were dialyzed for 4 h against 10 mM Na-Acetate buffer, pH 5.0 with the buffer changed after 2 h. 15 μl of sample was loaded into a BioATR II cell and 512 scans were collected at 2 cm−1 resolution under constant purging with nitrogen. Spectra were corrected for the buffer and water vapors. Absorption bands were resolved by Fourier self-deconvolution using Lorentzian parameters of 20 cm−1 bandwidth and a noise suppression factor of 0.3. Second derivatives of deconvoluted spectra were calculated using either 9-point (for spectra interpolation with Lorentz curves) or 17-point (in other cases) Savitzky-Golay smoothing. To deconvolute the original absorbance spectra to individual peaks, the Opus manual fitting procedure (Opus 4.2 software package, Bruker Optics) was employed by setting the peak maxima at wavelengths taken from FTIR 2nd derivative spectra. The minimal Euclidian distance between a spectrum and a fit was achieved by varying height and width of individual peaks.

For H/D exchange experiments two formats were used. In the format referred to as “dried samples”, the samples were dried off using Savant Speed Vac Concentrator (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and resolubilized in D2O immediately before scanning in BioATR II cell. 32 scans were collected for each time point during H/D exchange conducted for five hours. Spectra of D2O were collected under the same scanning conditions and at the same time points, and subtracted from the sample spectra. In the format referred to as “wet samples”, the samples were concentrated in Nanosep 100K centrifuge tubes at 5000g for 2 min and D2O was added up to the initial volume. This procedure was repeated 3 times to ensure D2O content being >99%. Considering that the whole procedure for replacing H2O to D2O takes ∼10 min, the five hours of H/D exchange included 10 min of dead-time. 128 scans were collected for each sample. In both formats, H/D exchange was monitored for five hours, the amide II to amide I ratio was calculated for each time point and normalized using FTIR spectra collected in H2O.

For the thermal denaturation assay, the temperature in the BioATR II cell was controlled using a Haake K10 Refrigerated Circulator Bath (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) operated with Opus/Protein software. Samples were heated from 20 °C to 80 °C by increasing the temperature in 10 deg. C increments over 15 min each and then cooled back to 20 °C in 10 deg. C decrements over 15 min each. 128 scans were taken at each temperature step. Spectra were corrected for the buffer and water vapors, spectra of which were measured under the same scanning and temperature conditions.

CD spectroscopy

CD spectra of PrP isoforms (∼0.25 mg/ml) were recorded in 5 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0 in a 0.1 cm cuvette with a J-810 CD Spectrometer (Jasco Inc., Easton, MD) at 50 nm/min scanning rate and resolution of 1 nm. Each spectrum represents the average of five individual scans after subtracting the background spectrum of the buffer. CD spectra were recorded for three independent preparations of R- or S-fibrils and were found to be identical for the same fibrilar types. For the sake of clarity, repeated spectra were omitted from the figures. To prepare sonicated fibrils, R- or S-fibrils were sonicated for 1 min in a bath sonicator Bransonic-2510 as previously described 59, and their spectra were collected under the same conditions.

Proteinase K digestion assay

PK digestion was performed in a reaction volume of 20 μl containing 100 μg/ml of fibrils and varying concentrations of PK (from 0.2 μg/ml to 50 μg/ml) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5 for 1 h at 37 °C. Reactions were quenched with 1 mM PMSF, then samples were treated with the sample buffer (2% SDS, 1.25 % β-mercaptoethanol, 2.25 M urea, heating for 15 min at 90 °C) and analyzed using 12% SDS-PAGE (precast NuPAGE gels, Invitrogen) followed by silver staining. For N-terminal sequencing PK-resistant fragments were transferred from SDS-PAGE to PVDF membrane, stained with Coomassie R-250 and analyzed at the Tufts University Core Facility (Boston, MA).

Fluorescent microscopy and spectroscopy

PTAA was synthesized as previously described 60. PrP fibrils (or monomers) and PTAA were mixed to final concentrations 5 μg/ml and ∼10 μg/ml, respectively, in 5 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0 and deposited on a cover glass (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Fluorescence images were recorded using an inverted microscope Eclipse TE2000 (Nikon, Japan) with a 1.3 aperture Plan Fluor ×100 with numerical aperture objective and two sets of filters: (i) Chroma 49002 ET-GFP (FITC/Cy2) for a green channel (excitation 470±20 nm, emission 525±25 nm) and (ii) Chroma 41006 Eth Bro for a red channel (excitation 535±25 nm, emission 610±30 nm). Images collected in the two channels were processed with WCIF ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD). Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded using FluoroMax-3 spectrofluorimeter (HORIBA Jobin Yvon Inc., Edison, NJ) with an excitation at 540 nm. Each spectrum represents the average of five individual scans.

For the thermal denaturation assay, PrP fibrils in 5 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0 were heated from 20 °C to 95 °C with a rate of 1 deg. C/min in PC-controlled RTE-111 Neslab thermostat. Aliquots were taken at 5 deg. C increments, diluted with 5 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.0 to a final PrP concentration of 5 μg/ml, incubated at room temperature for 30 min and mixed with PTAA at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Emission spectra were measured as described above.

Atomic Force Microscopy

AFM imaging was performed using Pico LE system (Agilent Technologies, Chandler, AZ) operated in the acoustic alternative current mode using a silicon cantilever PPP-NCH (Nanosensors, Switzerland) at the resonant frequency f0∼300 kHz. The AFM scanner was operated in tapping mode. The images (512×512 pixels) were collected at a scan rate of one line per second. To analyze the products of fibrillation reactions, samples were dialyzed in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.0 for 4 hours, changing the buffer after 2 hours. 10 μl of a sample (PrP concentration 20 μg/ml) were applied on a freshly cleaved piece of mica, incubated for 5 min at room temperature to adhere, washed by Milli Q water, and dried at room temperature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Cohen for assistance in X-ray data collection and Pamela Wright for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant NS045585 to (I.V.B.), the Knut and Alice foundation (K.P.R.N.) and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (K.P.R:N.)

The abbreviations used are

- PrPC

normal cellular isoform of the prion protein

- PrPSc

abnormal, disease-associated isoform of the prion protein

- PrP

recombinant prion protein

- α-PrP

recombinant prion protein refolded into monomeric α-helical conformation

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- PK

proteinase K

- H/D

hydrogen/deuterium

- PTAA

poly(thiophene-acetic acid)

- LCPs

luminescent conjugated polythiophenes

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Gua Z, Yau WM, Mattson MP, Tycko R. Self-Propagating, Molecular-Level Polymorphism in Alzheimer's b-Amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makarava N, Baskakov IV. The same primary structure of the prion protein yields two distinct self-propagating states. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15988–15996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800562200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka M, Chien P, Naber N, Cooke R, Weissman JS. Conformational variations in an infectious protein determine prion strain differences. Nature. 2004;6980:323–328. doi: 10.1038/nature02392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnan R, Lindquist S. Structural insight into a yeast prion illuminate nucleation and strain diversity. Nature. 2005;435:765–772. doi: 10.1038/nature03679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiltzius JJW, Landau M, Nelson R, Sawaya MR, Apostol MI, Goldschmidt L, Soriaga AB, Cascio D, Rajashankar R, Eisenberg D. Molecular mechanisms for protein-encoded inheritance. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2009;16:973–978. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13363–13383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzwolak W, Grudzielanek S, Smirnovas S, Ravindra R, Nicolini C, Jansen R, Loksztein A, Porowski S, Winter R. Ethanol-perturbed amyloidogenic self-assembly of insulin: looking for origins of amyloid strains. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8948–8958. doi: 10.1021/bi050281t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen JS, Dikov D, Flink JL, Hjuler HA, Christiansen G, Otzen DE. The changing face of glucagon fibrillation: structural polymorphism and conformational imprinting. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:501–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost B, Ollesch J, Wille H, Diamond MI. Conformational diversity of wild-type Tau fibrils specified by templated conformation change. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3546–3551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805627200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paravastu AK, Leapman RD, Yau WM, Tycko R. Molecular structural basis for polymorphism in Alzheimer's beta-amyloid fibrils. Proc Acad Natl Sci U S A. 2008;105:18349–18354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawaya MR, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, Ivanova MI, Sievers SA, Apostol MI, Thomson MJ, Balbirnie M, Wiltzius JJ, McFarlane HT, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Eisenberg D. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 2007;447:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jimenez JL, Nettleton EJ, Bouchard M, Robinson CV, Dobson CM, Saibil H. The protofilament structure of insulin amyloid fibrils. Proc Acad Natl Sci U S A. 2002;99:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142459399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosal WS, Morten IJ, Hewitt EW, Smith DA, Thompson NH, Radford SE. Competing Pathways Determine Fibril Morphology in the Self-assembly of beta-Microglobulin into Amyloid. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:850–864. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Avalos R, King CY, Wall J, Simon M, Caspar DLD. Strain-specific morphologies of yeast prion amyloid fibrils. Proc Acad Natl Sci U S A. 2005;102:10165–10170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504599102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldsbury C, Frey P, Olivieri V, Aebi U, Muller SA. Multiple Assembly Pathways Underlie Amyloid-b Fibril Polymorphysms. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:282–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson M, Bocharova OV, Makarava N, Breydo L, Salnikov VV, Baskakov IV. Polymorphysm and Ultrastructural Organization of Prion Protein Amyloid Fibrils: An Insight from High Resolution Atomic Force Microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2006;358:580–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makarava N, Bocharova OV, Salnikov VV, Breydo L, Anderson M, Baskakov IV. Dichotomous versus palm-type mechanisms of lateral assembly of amyloid fibrils. Prot Science. 2006;15:1334–1341. doi: 10.1110/ps.052013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sim VL, Caughey B. Ultrastructures and strain comparison of underglycosylation scrapie prion fibrils. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:2031–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberski PP, Brown P, Xiao SY, Gajdusek DC. The ultrastructural diversity of scrapie-associated fibrils isolated from experimental scrapie and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Comp Pathol. 1991;105:377–386. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(08)80107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krimm S, Bandekar J. Vibrational Spectroscopy and Conformation of Peptides, Polypeptides, and Proteins. Advances in Protein Chemistry. 1986;38:297–328. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60528-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perczel A, Fasman GD. Quantitative analysis of cyclic beta-turn models. Protein Science. 1992;1:378–395. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigurdson CJ, Nilsson KPR, Hornemann S, Manco G, Polymenidou M, Schwarz P, Leclerc M, Hammarstrom P, Wutrich K, Aguzzi A. Prion strain discrimination using luminiscent conjugated polymers. Nature Methods. 2007;4:1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almstedt K, Nyström S, Nilsson KPR, Hammarström P. Amyloid fibrils of human prion protein are spun and woven from morphologically disordered aggregates. Prion. 2009;3:224–235. doi: 10.4161/pri.3.4.10112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wille H, Bian W, McDonald M, Kendall A, Colby DW, Bloch L, Ollesh J, Borovinskiy AL, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB, Stubbs G. Natural and synthetic prion structure from X-ray fiber diffraction. Proc Acad Natl Sci U S A. 2009;106:16990–16995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909006106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malinchik SB, Inouye H, Szumowski KE, Kirschner DA. Structural Analysis of Alzheimer's (1-40) Amyloid: Protofilament Assembly of Tubular Fibrils. Biophys J. 1998;74:537–545. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77812-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunde M, Serpell LC, Bartlam M, Fraser PE, Pepys MB, Blake CC. Common core structure of amyloid fibrils by synchrotron X-ray diffraction. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:729–739. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahn TR, Makin OS, Morris KL, Marshall KE, Tian P, Sikorski P, Serpell LC. The Common Architecture of Cross-beta Amyloid. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:717–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostapchenko VG, Makarava N, Savtchenko R, Baskakov IV. The polybasic N-terminal region of the prion protein controls the physical properties of both the cellular and fibrillar forms of PrP. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1210–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nandi PK, Leclerc E, Marc D. Unusual Property of Prion Protein Unfolding in Neutral Salt Solution. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11017–11024. doi: 10.1021/bi025886t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caughey B, Raymond GJ, Bessen RA. Strain-dependent differences in β-sheet conformations of abnormal prion protein. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32230–32235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomzig A, Spassov S, Friedrich M, Naumann D, Beekes M. Discriminating Scrapie and Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Isolates by Infrared Spectroscopy of Pathological Prion Protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spassov S, Beekes M, Naumann D. Structural differences between TSEs strains investigated by FT-IR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:1138–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makarava N, Kovacs GG, Bocharova OV, Savtchenko R, Alexeeva I, Budka H, Rohwer RG, Baskakov IV. Recombinant prion protein induces a new transmissible prion disease in wild type animals. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makarava N, Ostapchenko VG, Savtchenko R, Baskakov IV. Conformational switching within individual amyloid fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14386–14395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900533200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baskakov IV. Switching in amyloid structure within individual fibrils: implication for strain adaptation, species barrier and strain classification. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2618–2622. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Z, Krause G, Reif B. Sructure and orientation of peptide inhibitors bound to beta-amyloid fibrils. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:760–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chalifour RJ, McLaughlin RW, Lavoie L, Morissette C, Tremblay N, Boulé M, Sarazin P, Stéa D, Lacombe D, Tremblay P, Gervais F. Stereoselective interactions of peptide inhibitors with the beta-amyloid peptide. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34874–34881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esteras-Chopo A, Pastor MT, Serrano L, Lopez de la Paz M. New strategy for the generation of specific D-peptide amyloid inhibitors. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:1372–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan KM, Baldwin M, Nguyen J, Gasset M, Serban A, Groth D, Mehlhorn I, Huang Z, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Conversion of α-helices into β-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10962–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gasset M, Baldwin MA, Fletterick RJ, Prusiner SB. Perturbation of the secondary structure of the scrapie prion protein under conditions that alter infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kocisko DA, Lansbury PT, Jr, Caughey B. Partial unfolding and refolding of scrapie-associated prion protein: evidence for a critical 16-kDa C-terminal domain. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13434–13442. doi: 10.1021/bi9610562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sajnani G, Pastrana MA, Dynin I, Onisko B, Requena JR. Scrapie prion protein structural constraints obtained by limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bocharova OV, Breydo L, Salnikov VV, Gill AC, Baskakov IV. Synthetic prions generated in vitro are similar to a newly identified subpopulation of PrPSc from sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease PrPSc. Prot Science. 2005;14:1222–1232. doi: 10.1110/ps.041186605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bocharova OV, Makarava N, Breydo L, Anderson M, Salnikov VV, Baskakov IV. Annealing PrP amyloid firbils at high temperature results in extension of a proteinase K resistant core. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2373–2379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dzwolak W, Loksztejn A, Smirnovas V. New insights into the self-assembly of insulin amyloid fibrils: an H-D exchange FT-IR study. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8143–8151. doi: 10.1021/bi060341a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chatani E, Goto Y. Structural stability of amyloid fibrils of beta(2)-microglobulin in comparison with its native fold. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1753:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Englander SW, Mayne L, Bai Y, Sosnick TR. Hydrogen exchange: The modern legacy of Linderstrom-Lang. Protein Science. 1997;6:1101–1109. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung EW, Nettleton EJ, Morgan CJ, Gross M, Miranker A, Radford SE, Dobson CM, Robinson CV. Hydrogen exchange properties of proteins in native and denatured states monitored by mass spectrometry and NMR. Prot Science. 1997;6:1316–1324. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olofsson A, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Ohman A. The solvent protection of alzheimer amyloid-beta-(1-42) fibrils as determined by solution NMR spectroscopy. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:477–483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flechsig E, Shmerling D, Hegyi I, Raeber AJ, Fischer M, Cozzio A, von Mering C, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C. Prion protein devoid of the octapeptide repeat region restores susceptibility to scrapie in PrP knockout mice. Neuron. 2000;27:399–408. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers M, Yehiely F, Scott M, Prusiner SB. Conversion of truncated and elongated prion proteins into the scrapie isoform in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3182–3186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moroncini G, Kanu N, Solforosi L, Abalos G, Telling GC, Head M, Ironside J, Brockes JP, Burton DR, Williamson RA. Motif-grafted antibodies containing the replicative interface of cellular PrP are specific for PrPSc. Proc Acad Natl Sci U S A. 2004;101:10404–10409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403522101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solforosi L, Bellon AB, Schaller M, Cruite JT, Abalos GC, Williamson RA. Toward Molecular Dissection of PrPC=PrPSc Interactions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7465–7471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Y, Breydo L, Makarava N, Yang Q, Bocharova OV, Baskakov IV. Site-specific conformational studies of PrP amyloid fibrils revealed two cooperative folding domain within amyloid structure. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9090–9097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608623200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deleault NR, Harris BT, Rees JR, Supattapone S. Formation of native prions from minimal components in vitro. Proc Acad Natl Sci U S A. 2007;104:9741–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702662104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deleault NR, Lucassen RW, Supattapone S. RNA molecules stimulate prion protein conversion. Nature. 2003;425:717–720. doi: 10.1038/nature01979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ceoghegan JC, Valdes PA, Orem NR, Deleault NR, Williamson RA, Harris BT, Supattapone S. Selective incorporation of polyanionic molecules into hamster prions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36341–36353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704447200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Makarava N, Lee CI, Ostapchenko VG, Baskakov IV. Highly promiscuous nature of prion polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36704–36713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun Y, Makarava N, Lee CI, Laksanalamai P, Robb FT, Baskakov IV. Conformational stability of PrP amyloid firbils controls their smallest possible fragment size. J Mol Biol. 2008;376:1155–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ding L, Jonforsen M, Roman LS, Andersson MR, Inganäs O. Photovoltaic cells with a conjugated polyelectrolyte. Synth Met. 2000;110:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Novitskaya V, Makarava N, Bellon A, Bocharova OV, Bronstein IB, Williamson RA, Baskakov IV. Probing the conformation of the prion protein within a single amyloid fibril using a novel immunoconformational assay. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15536–15545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.