Abstract

Amitriptyline is sometimes used to treat arm pain related to repetitive use, but rigorous evidence of its benefit is lacking. This randomized controlled trial investigated whether amitriptyline provided greater pain relief or improved arm function than a placebo pill in adults with arm pain associated with repetitive use that had persisted for at least three months. Participants (N=118) were randomly assigned to receive 25 mg of amitriptyline or a placebo pill for 6 weeks. The primary outcome was intensity of pain (10-point numerical rating scale) and secondary outcomes were arm symptoms, arm function, grip strength, mood and sleep. Assessments were done at baseline, 3 and 6 weeks of treatment, and one month after treatment ended. Changes in arm pain were not statistically significant. However, the amitriptyline group improved more than the placebo group in arm function (p=0.023) and sense of well-being (p=0.034). In a longitudinal analysis, the amitriptyline group’s arm function score improved 0.45 points per week faster than placebo after adjusting for subject characteristics (p=0.015). At the treatment’s midpoint, the amitriptyline group reported more “troublesome side-effects” than the placebo group (52.5% vs. 27.1%, p=0.005), but this difference decreased by end of treatment (30.5% vs 22.0%, p=0.30). The most frequent side effect was drowsiness. In conclusion, this study found that low-dose amitriptyline did not significantly decrease arm pain among these participants but did significantly improve arm function and well-being. Future research is needed to explore the effects of higher doses and longer duration of treatment.

1. Introduction

Arm pain from repetitive use – termed repetitive motion disorders (RMDs) [23], cumulative trauma disorders, work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) [25,1] or repetitive strain injuries [35,34] - is an important cause of workplace disability. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, repetitive motion including grasping tools, scanning groceries, and typing has resulted in the longest absences from work among leading events and exposures [3]. Like low back pain, RMDs of the upper extremity can derive from tendons, nerves, or muscles and encompass a wide range of diagnoses, including lateral and medial epicondylitis, tendonitis, and carpal tunnel syndrome, as well as non-specific arm pain [35,25,23,34] Most strain syndromes resolve with decreased use, changes in positions, or adjustment of the workspace along with conservative treatment such as anti-inflammatory medications, splinting, and physical therapy. When symptoms persist, steroid injections or surgical release have been used for specific conditions, such as carpal tunnel syndrome and DeQuervain’s tendonitis. In other cases, low dose tricyclic antidepressants have been tried, particularly when there have been associated sleep difficulties [25].

Tricyclic antidepressants have been shown to be effective in decreasing pain associated with diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia [17,18,21,15]. In addition to neuropathic conditions, tricyclics have been found to be useful in the treatment of fibromyalgia and headaches [8,10,15,2]. Antidepressants also have been used to treat chronic low back pain and found to be effective in reducing pain severity, but with conflicting evidence about improvement in functional status [29,31]. Despite similarities between chronic upper extremity syndromes and chronic low back pain, we could find no randomized controlled studies examining the effectiveness of treatment of arm RMDs with tricyclic antidepressants.

In this randomized clinical trial (RCT), we examined whether treatment with low dose amitriptyline was better than a placebo pill in reducing arm pain and increasing arm function in persons with persistent pain due to repetitive use.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design

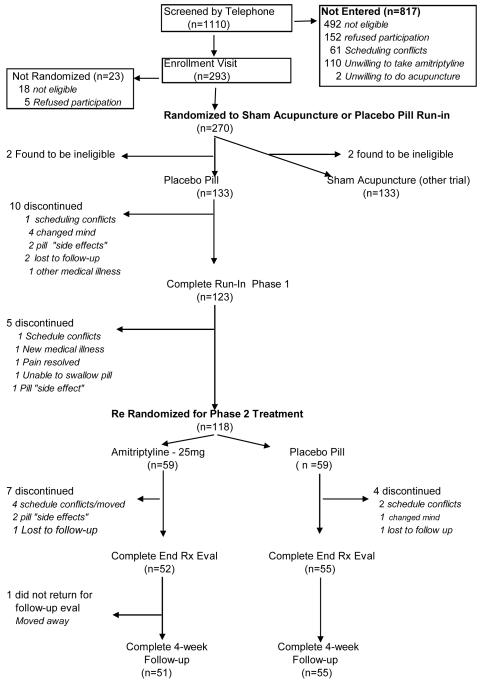

This double-blinded, placebo-controlled amitriptyline trial followed a 2-week placebo run-in that compared sham acupuncture with a placebo pill [11]. A parallel RCT compared true acupuncture to sham acupuncture [9] (see Figure 1). Participants who were assigned to placebo pill during the run-in period were then seamlessly re-randomized at its end to either amitriptyline (25mg) or continued placebo pill. Study participants took one tablet at bedtime during the 2-week placebo run-in phase and during the 6-week treatment phase (total of 8 weeks). During treatment, a research assistant called them every other week to examine their progress and respond to questions. Follow-up assessments were performed at the end of the placebo run-in (which is the baseline for this study), mid-treatment, end-of-treatment, and four weeks after treatment ended. Study assessments were performed at an academically affiliated community hospital

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram for Amitriptyline Trial

2.2 Study participants

Men and women were recruited between June 2001 and April 2003 from the greater Boston and Cambridge communities through advertisements and referrals from health professionals. Research assistants performed telephone-screening interviews to determine eligibility and willingness to participate. Because participants were initially randomly assigned to either the pill or acupuncture arm, they had to fulfill requirements for both trials. To be eligible, an individual had to be an adult (at least 18years old) with distal upper extremity pain associated with repetitive use or prolonged static postures that had persisted for at least 3 months, had received some prior treatment, and reported pain intensity of 3 or greater on a 10-point numerical pain scale. We included individuals with a range of clinical diagnoses involving the tendons, soft tissues and nerves of the arm, as well as those with non-specific arm symptoms related to movement (“overuse strain syndrome”). We excluded persons with systemic connective tissue or muscular diseases, neurological disorders (e.g.cerebrovascular accidents, cervical disc disease), pregnancy, acute trauma to the affected arm, use of medications that interact with amitriptyline, medical illnesses that could be adversely affected by amitriptyline, and previous treatment with amitriptyline for arm pain, or prior use of amitriptyline within 1 year for any problem . Participants were allowed to continue taking anti-inflammatory medications, and to continue with other non-study treatments in progress, but they were discouraged from starting new treatments during the study.

During their enrollment visits, candidates provided written informed consent, completed questionnaires, and underwent grip strength testing with a Jamar dynamometer and pinch meter. The study’s occupational medicine physicians (RG and SM) performed targeted physical examinations to identify reasons for exclusion and to assign clinical diagnosis(es) for the arm pain using previously defined criteria [28,25].

During the informed consent process, potential participants were told they would be randomly assigned to either the amitriptyline or acupuncture trial, and that they had a 50% chance of receiving active treatment at some time during the study. We offered participants courtesy treatment with amitriptyline or true acupuncture after their participation if they had received only placebo treatment during the study. They also received information about possible side effects of treatment. The institutional review boards of the Cambridge Health Alliance, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, and Harvard School of Public Health approved the study protocol.

At enrollment, participants were randomly assigned to either the placebo pill or the sham acupuncture group using a permuted block randomization with variable block sizes and assignments sealed in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. The person performing this randomization and preparing the envelopes was at a separate site from the study, and had nothing to do with the study participants or the collection of data. At the end of the run-in phase, participants who completed the run-in were re-randomized to continue on placebo treatment or to take active treatment with amitriptyline. In order to be sure that those individuals whose pain had declined to less than 3 during the placebo run-in were equally distributed between the placebo and active treatment groups, the randomization was stratified by the individual’s level of pain (< 3 or ≥3 on a 10 point scale). An administrative assistant not involved in recruitment or data collection selected and opened envelopes in the sequence and recorded the assignment in a confidential log.

2.3 Intervention

Participants were instructed to take one capsule each evening to minimize daytime drowsiness. The hospital’s research pharmacy custom-designed identical opaque placebo or amitriptyline capsules. The placebo capsule contained cornstarch, and the amitriptyline capsule contained cornstarch plus 25 mg of amitriptyline. If participants complained of side effects during the study, the physician could reduce the dose by half or more.

2.4 Blinding

Participants were blinded throughout the study to whether they were receiving placebo or active treatment. Research assistants involved in data collection were also blinded to treatment assignment. To test the success of blinding, participants were asked at each data collection point whether they believed they were receiving active or placebo pill.

2.5 Outcome Measures

The primary outcome variable was self-reported intensity of pain with movement in the more severely affected arm during the preceding week, measured on a 10-point numerical rating scale ranging from no pain (1) to the most intense pain imaginable (10) [4]. Secondary outcome variables included: the Levine Symptom Severity Scale which assesses the frequency, severity, and duration of upper extremity symptoms as the mean score of eleven items each assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms [13] ; Upper Extremity Function Scale (UEFS) which rates the impact of symptoms on eight types of arm function on 10-point scales where the total score can range from 8 to 80 with higher scores indicating more functional impairment [26]; grip strength measured by a Jamar hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston Inc, Bolingbrook, IL 60144) and interference with sleep because of arm problems using one of the questions from the UEFS ( “problem with sleeping”), a 10 point scale, in which “1” represents no problem, and “10” major problem-can’t do it all [26]. In addition, at the time of enrollment and the end of treatment, we assessed: depression and mood states using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D) that contains 20 items, rated 0-3, composite score 0-60, with higher scores reflecting more depression, and a score >16 indicating clinical depression [27,19] and general well-being using an abbreviated General Well Being Schedule (questions 1-14) which has a composite score ranging from 0-84, with higher scores indicating greater well-being [5,19]. The outcome measures used for the analyses for both primary and secondary variables were the changes measured in the variables over the treatment period.

At each assessment point, participants were asked if they had experienced any troublesome side effects during the preceding two weeks that they believed were due to the pill, and then were provided with a checklist for specifying type of side effect. Participants brought in their pill bottles, and the research assistant did pill counts to measure adherence to the regimen.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

Sample size estimates for the treatment phase were based on changes in the primary outcome pain score and findings observed in previous pain studies [8,6,10]. We estimated that 60 subjects in each treatment group would provide 80% power to detect a difference of 1.45 points on the 10-point pain scale.

Changes on each outcome measure were calculated by subtracting baseline values (end of run-in) from end-of-treatment results. We used intention-to-treat analyses to compare changes in the amitriptyline and placebo pill groups. For participants who dropped out during treatment, we imputed missing data using a last value carried forward approach. All reported p-values are 2-sided. T-tests were used to test for statistical differences of means and chi-square tests (or Fisher’s exact test) for proportions.

To examine longitudinal trends in outcome scores, we used the baseline, midtreatment, and end-of-treatment points to fit regression models using generalized estimating equations using the SAS program [14,36]. Independent variables included study week, treatment group, and the interaction between these two variables. We also examined the effects of different covariates in these regression models using multivariate analyses.

3. Results

3.1 Study Population

Figure 1 displays the flow of the study population. A total of 1110 people completed telephone screening between June 2001 and April 2003. Of these, 817 were not eligible or refused to participate, leaving 293 people who attended the enrollment visit. During this visit, 23 people were found to be ineligible or chose not to enroll. Hence, 270 people were randomized into the placebo run-in phase: 135 to placebo pill and 135 to sham acupuncture device. During the 2-week placebo run-in and pre-treatment phase 2 participants were found to be ineligible and 15 withdrew leaving 118 in the pill group to be randomized to amitriptyline (n=59) and placebo pill (n=59). Of these, 52 and 55 respectively completed the 6 weeks of treatment, and 51 and 55 returned for post-treatment assessment, respectively.

At the time of enrollment, intensity of pain, levels of secondary outcome measures, and other current treatments for arm pain were similar between those who were ultimately randomized to amitriptyline or to placebo pill except for slight higher (worse) mean function score for those in the amitriptyline group . During the placebo run-in period, the intensity of pain decreased by 0.5 points, from a mean of 5.2 (± 1.7) to 4.7 (± 1.8) (p=0.11) in those who were subsequently randomized to amitriptyline; and decreased by 0.8 points, from 5.1 ( ± 1.6) to 4.3 (± 1.8) (p=0.02) in those who continued with placebo pill. Upper extremity function improved in the amitriptyline group by 3.1 points (p=0.11) from 26.5 (± 12.9) to 23.4 (± 11.87); and those who continued with placebo pill improved by 2.5 points (p=0.19) from 22.0 (± 10.02) to 19.5 (± 10.91).

At the start of the treatment trial, the amitriptyline and placebo pill groups were well-balanced on all variables (Table 1) and there were no statistically significant differences. Although the function score was slightly higher in the amitriptyline group, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.06). Two-thirds of participants had symptoms for 1 year or more. Both groups were highly educated, with over threequarters completing at least 4 years of college. Sleep disturbance was not a problem among the study participants, as demonstrated by the low baseline mean score of 1.7 on the 10 point scale.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics [mean ± SD or n (%)]

| Variable | Amitriptyline (n = 59) |

Placebo Pill (n = 59) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 36.1 ± 10.8 | 38.9 ± 11.6 |

| Female | 37 (62.7) | 29 (49.2) |

| Non-white | 10 (17.0) | 13 (22.0) |

| At least 4 years of college | 49 (83.1) | 44 (74.6) |

| Symptom duration < 1 year | 16 (27.1) | 21 (35.6) |

| Current NSAID use for arm pain | 30 (50.9) | 32 (54.2) |

| Current antidepressant use | 6 (10.2) | 4 (6.8) |

| Expected pain in 2 weeks | ||

| No additional treatment | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 1.7 |

| With pill | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 1.6 |

| Current stress at work1 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.0 |

| Satisfaction with current job2 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.0 |

| Clinical Diagnoses | ||

| Tendonitis/epicondylitis | 44 (74.6) | 39 (66.1) |

| Neuropathic/neuralgia | 8 (13.6) | 5 (8.5) |

| Non-specific | 5 (8.5) | 8 (13.6) |

| Other diagnosis | 2 (3.4) | 7 (11.9) |

| CES-depression scale score | 9.7 ± 7.1 | 9.6 ± 7.1 |

| CES- # with score ≥16 | 11 (18.6) | 9 (15.3) |

| General Well-Being Score | 64.7 ± 9.4 | 64.9 ± 10.1 |

| Intensity of Pain (10 point scale) | 4.7 ± 1.8 | 4.3 ± 1.8 |

| Severity of Arm Symptoms | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| Upper extremity function scale | 23.4 ± 11.9 | 19.5 ± 10.9 |

| Sleep problem (10 point scale) | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.5 |

| Grip strength (pounds) | 65.0 ± 24.6 | 63.9 ± 24.0 |

Degree of stress at work or school (5 pt scale: 1= “little or no stress” to 5 “severe stress”)

Degree of satisfaction with current job (5 pt. scale: 1= “very satisfied” to 5 “not satisfied at all”

The participants reported up to three repetitive tasks that they felt contributed to the onset of their arm symptoms (Table 2). The single most frequent task was computer keyboarding or use of the mouse. . The majority of the participants had service-related jobs in business, computers, education, personal care, or health care; 25 were part-time or full-time students; and 5 worked in construction or material handling. Only two persons in each group were either receiving, or had pending, worker compensation benefits.

Table 2.

Repetitive tasks contributing to onset of arm, wrist or hand symptoms

| Repetitive Task | Amitriptyline n=59 |

Placebo n=59 |

|---|---|---|

| No. Tasks (%) | No. Tasks (%) | |

| Keyboarding/mousing | 41 (69.5) | 46 (78.0) |

| Playing musical instrument | 9 (15.3) | 9 (15.0) |

| Construction, mechanical repair, assembly work |

6 (10.1 ) | 15 ( 25.4) |

| Materials handling | 6 (10.2) | 9 (15.3) |

| Arts/crafts work | 4 (6.8) | 2 (3.4) |

| Home cleaning | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.7) |

| Handwriting | 2(3.4) | 0( 0) |

| Other | 20 (33.9) | 14 (23.7 ) |

| Total Tasks | 90 | 96 |

During the enrollment visit, the examining physician assigned clinical diagnoses for the causes of arm pain, noting the one diagnosis that was the most prominent or important. The frequencies of “most important” diagnoses are summarized in Table 3. The majority fell into the categories of tendonitis or epicondylitis.

Table 3.

Frequencies of Most Important Diagnoses

| Amitriptyline N (%) n=59 |

Placebo Pill N (%) n=59 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Tendonitis/Epicondylitis Group | ||

| Wrist/Forearm Flexor Tendonitis or Tenderness |

11 (18.6) | 7 (11.9) |

| Wrist/Forearm Extensor Tendonitis or Tenderness |

14 (23.7) | 12 (20.3) |

| Medial Epicondylitis | 6 (10.2) | 5 (8.5) |

| Lateral Epicondylitis | 9 (15.3) | 10 (17.0) |

| DeQuervain’s Tendonitis | 4 (6.8) | 5 (8.5) |

| Neuropathic/Neuralgia Group | ||

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | 6 (10.2) | 3 (5.1) |

| Cubital tunnel syndrome | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.4) |

| Non-specific upper extremity pain | 5 (8.5) | 8 (13.6) |

| Other diagnoses | 2(3.4) | 7 (11.9%) |

| Total | 59 | 59 |

3.2 Outcomes

During the treatment period, there were no significant differences in the mean changes in pain (primary outcome), symptom severity, grip strength or sleep difficulties (Table 4). However, upper extremity function in the amitriptyline group improved by 3.9 points compared to the placebo group’s change of 0.8, and the difference was statistically significant (p=0.023). The amitriptyline group also showed small, but statistically greater improvement in General Well-Being scale (p=0.034). Change in depression score was in the direction of improvement but did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.066).

Table 4.

Changes in outcome measures at the end of treatment

| Amitriptyline (n=59) |

Placebo Pill (n=59) |

Difference | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | [95% CI] | ||

| Pain (10 point scale) | ||||

| Baseline | 4.7 (1.8) | 4.3 (1.8) | ||

| End Rx | 4.0 (1.8) | 3.9 (1.9) | 0.277 | |

| Change | −0.7 (1.5) | −0.4 (1.8) | − 0.3 [−0.95, 0.28] | |

| Symptom Severity Scale1 | ||||

| Baseline | 2.1 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.5) | ||

| End Rx | 1.9 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.5) | 0.518 | |

| Change | −0.2 (0.4) | −0.1 (0.4) | −0.1 [−0.19, 0.10] | |

| Upper Extremity Function Scale 2 | ||||

| Baseline | 23.4 (11.9) | 19.5 (10.9) | ||

| End Rx | 19.6 (10.6) | 18.7 (11.9) | 0.023 | |

| Change | −3.9 (7.4) | −0.8 (7.0) | −3.1 [−5.67, −0.44] | |

| Grip Strength (pounds) | ||||

| Baseline | 65.0 (24.6) | 63.9 (24.0) | ||

| End Rx | 65.7 (25.6) | 63.2 (25.1) | 0.411 | |

| Change | 0.8 (8.6) | −0.6 (9.9) | 1.4 [−1.97, 4.79] | |

| Sleep (10 point scale) | ||||

| Baseline | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.5) | ||

| End Rx | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.8 (1.5) | 0.100 | |

| Change | −0.3 (1.0) | 0.1 (1.2) | −0.4 [−0.74, 0.07] | |

| General Well-Being 3 | ||||

| Baseline | 64.7 (9.4) | 64.9 (10.1) | ||

| End Rx | 66.4 (8.3) | 64.0 (10.6) | 0.034 | |

| Change | 1.7 (6.9) | −0.9 (6.0) | 2.6 [0.20, 4.95] | |

| CES Depression 4 | ||||

| Baseline | 10.0 (7.7) | 9.6 (6.9) | ||

| End Rx | 8.4 (6.9) | 10.2 (7.7) | 0.066 | |

| Change | −1.6 (6.9) | 0.7 (6.4) | −2.3 [−4.69, 0.15] | |

Levine’s Symptom Severity Scale: mean score on eleven items, each scored on a 5 point scale. A higher mean score is worse.

Pransky’s Upper Extremity Function Scale: 8 types of arm function scored on 10 point scales, with higher scores indicating worse function; total score 8-80

Abbreviated General Well-Being Schedule: composite score 0-84 with higher scores indicating greater well-being

CES depression scale: composite score 0-60 with higher scores indicatng more depression

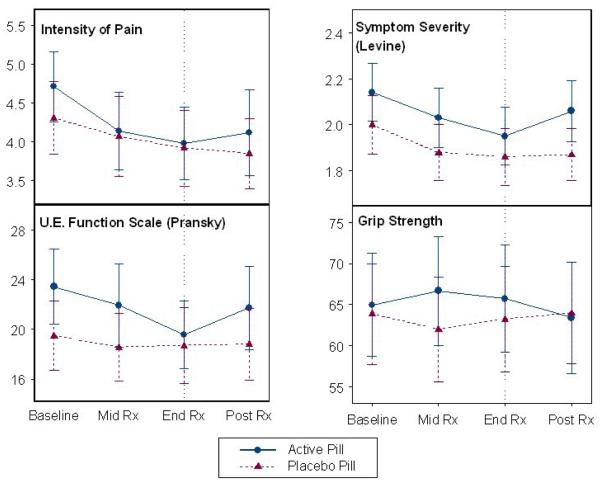

In the initial longitudinal analysis the rate of weekly improvements in arm function (UEFS) was 0.51 points/week faster in the amitriptyline group compared to the placebo group after adjusting for the baseline function score (Table 4). The improvement in the arm function score remained significant (0.45 points/week faster than placebo) after multiple regression analyses adjusting for age, sex, duration of pain, expectation of relief, NSAID use, and baseline function score (p= 0.015). No statistically significant differences were found in the rate of change for arm pain or arm symptom severity scores after adjustment for baseline values (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal changes (mean ± 95 % confidence interval) of outcome measures in pill treatment groups. Vertical line indicates end of treatment period.

Assessments done one month after treatment stopped showed that there was mild worsening of function and symptoms in the amitriptyline group (figure 2).

3.3 Blinding

At the end of the treatment period, the proportion of participants who believed they were receiving active treatment was slightly higher in the amitriptyline group than in the placebo group, but this difference was not significant. (64.4% versus 49.2%, p = 0.094).

3.4 Adherence

At the midpoint of treatment, mean pill adherence based upon pill counts was 90% in amitriptyline group and 92% for the placebo group. Comparable figures at the end of treatment were 87% and 89%, respectively.

3.5 Influence of treatment side effects on study outcomes

There were no serious adverse effects attributable to amitriptyline. At each assessment point, participants were asked if they had experienced any side effects during the preceding two weeks that they attributed to the pill treatment and, if so, to indicate the type(s) and severity(ies) of symptoms on a checklist. During the treatment period, more of the amitriptyline group (53%) reported side-effects at the midpoint of treatment than those in the placebo group (53% vs.27%, p=0.005). By the end of the treatment period, the frequency of reported side effects declined, and there was no statistical difference between amitriptyline and placebo groups (31% vs. 22%, p= 0.30). Drowsiness was the most frequent side effect reported and occurred in 41% of the amitriptyline group versus 15% of the placebo groups (p=0.002). During treatment, two participants in the amitriptyline group discontinued treatment because of presumed side effects.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest randomized controlled trial to examine very low dose amitriptyline (25mg) for treatment of distal arm pain associated with repetitive use. The study was carefully designed, demonstrated excellent adherence to prescribed regimens and subject blinding, and had very few dropouts. This study did not demonstrate that very low dose amitriptyline reduced arm pain more than placebo. However, we did observe greater improvement in arm function and general well being. In the longitudinal analysis, the weekly improvement in arm function score was found to be faster in the amitriptyline group compared to the placebo group after adjusting for the baseline function score and other variables. The level of improvement seen in function and well being (at this low dose and short time frame) was small and may not be clinically discernible. We cannot exclude the possibility that some of the observed significant findings may be false positives, particularly if making a correction for multiple comparisons, but most of the measures demonstrating improvement favored the amitriptyline group. The finding that arm function scores worsened in the amitriptyline group, but not in the placebo group, after the treatment stopped also suggests reversal of positive treatment effects. Overall, treatment with 25 mg per day of amitriptyline was well-tolerated despite some reports of daytime drowsiness. The observation that side effects decreased in frequency over the course of treatment is consistent with reports that tolerance develops to most anticholinergic effects within a few weeks[7].

Consideration of the mechanisms of action of amitriptyline has implications for the interpretation of its effects in people with arm pain and dysfunction due to repetitive use. Amitriptyline inhibits reuptake of both norepinephrine and serotonin, which is thought to be part of the mechanism of action for its anti-depressive effects [22]. The mechanism for the analgesic action is not entirely understood, but appears to be mostly associated with the effects on norepinephrine[15,31]. In a rat study involving local injection of various tricyclic antidepressants into the sciatic nerve, amitriptyline was found to demonstrate the best efficacy as a long acting local anesthetic [32]. The authors propose, along with other reports, that the ability to act as a potent use-dependent blocker of Na+ channels may in part explain its analgesic actions in vivo. Studies of treatment for chronic low back pain have found that the antidepressants that inhibit norepinephrine reuptake (tricyclic or tetracyclic antidepressants) were more effective than serotonin reuptake inhibitors [31]. The impact of tricyclics medications on functional status is less clear [31]. During the short time frame (6 weeks of treatment) of our study, there appeared to be greater improvement on reported function measures than intensity of pain. These improvements were independent of effect on sleep, since our population reported little sleep difficulties. We also observed a small improvement in the sense of well being, and it is difficult to know if that was a contributing factor to the increased function, or possibly an effect. The analgesic effects of low-dose amitriptyline have been considered to be independent from its antidepressant effects, since improvements have been seen in persons without depression [17,16,10,15]. Yet this observation does not exclude the possibility of improvement in the sense of well being, and consequently a feeling of being able to do more. One study, for example, noted an improvement in wellbeing in fibromyalgia patients without a clinical diagnosis of depression [8] .

The main limitations of the study were the low dose of amitriptyline used and the relatively short 6-week duration of treatment. We chose 25mg per day because this is a frequent dose used to treat fibromyalgia, musculoskeletal disorders, and mild neuropathic pain conditions and because we wanted to limit the medication side effects associated with higher doses [20]. Larger and more durable effects, perhaps including pain reduction, might have been observed with higher doses of amitriptyline and/or longer periods of treatment. The 6-week treatment period was selected as a compromise between the practicalities of enrolling participants and maintaining adherence to study protocols and the duration of treatment likely needed to have substantial effects on symptoms. Longer treatment, which would be common in clinical practice, might yield more clinically significant and sustained results, even at this low dose. In addition, although other studies have found tricylics to be helpful with sleep, particularly for those with fibromyalgia, [20,7,8], we were limited in exploring the impact on sleep given the low prevalence of sleep problems in our study population. Since the mean baseline sleep score was 1.7, very close to the lowest anchor point of 1.0 (“no sleep problems”) on the 10 point sleep scale, there was little room to demonstrate improvement with treatment. Interestingly, our study suggested improvement in some parameters with amitriptyline even in the absence of sleep problems.

We did not measure serum levels of amitriptyline since we were using very low doses, and so did not need to reach a specific therapeutic level, nor were we concerned about monitoring to avoid toxic high levels.. We used pill counts as a measure of adherence rather than plasma serum levels because it was much less bothersome for participants and less complicated for implementation

Since most participants indicated that computer work was an important cause of their arm pain, our results may not generalize to other groups with arm strain problems, such as assembly-line workers. The large and ever-increasing number of computer workers and numerous reports of arm and hand problems in these individuals [33,24,30,12], however, underscores the importance of effective treatment for this population. Moreover, it is highly likely that people with similar arm problems will exhibit similar responses to amitriptyline regardless of the precipitating tasks. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications have been the primary starting treatment for these persistent arm problems, yet there may be circumstances in which they are not medically desirable or are contraindicated, or prove to be ineffective.

In summary, the ideal is to prevent or limit arm symptoms by designing workspaces to be more ergonomic. However, sometimes symptoms arise and persist despite various adjustments. Although this study did not provide evidence of efficacy of low dose amitriptyline in reducing overuse arm pain during a short treatment time, it did suggest improvements in function and mood that are encouraging. Future investigations that evaluate the effects of titrating higher doses, and providing treatment over longer periods of time are needed to more fully assess whether amitriptyline will prove to be a useful treatment for persons with arm pain due to repetitive use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants 1RO1 AT00402-01 and 1 K24 AT004095 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. The authors thank Lin Nulman and Melbeth Marlang, research assistants for recruitment and evaluation of participants; Joyce Singer for assistance in screening; Catherine E. Kerr, Ph.D.for her assistance with expectancy issues and assisting with assessments; Hyun Kim statistics assistant; Anna T.R. Legedza, Sc.D for initial organization of the data base; Patricia Muldoon, administrative assistant; Jacqueline Savetsky and Andrea Hrbek for additional administrative support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No author had or now has any financial interest in any for-profit organization related to the treatment of patients with repetitive strain injuries or related disabling conditions. Dr. Rose Goldman sometimes serves as a paid expert witness, independent medical examiner, and/or consultant in workers’ compensation and disability cases that might involve musculoskeletal problems and repetitive strain injuries.

References

- [1].Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 62: Diagnosis and Treatment of Worker-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Upper Extremity. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [2].Ashina S, Bendtsen L, Jensen R. Analgesic effect of amitriptyline in chronic tensiontype headache is not directly related to serotonin reuptake inhibition. Pain. 2004;108:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Department of Labor) Repetitive motion leads to longest work absences.

- [4].Daut RI, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain. 1983;17:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fazio AF. A concurrent validational study of the NCHS Well-Being Schedule. [PubMed]

- [6].Garfinkel MS, Singhal A, Katz W. Yoga based intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome. JAMA. 1998;280:1601–1603. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Godfrey RG. A Guide to the Understanding and Use of Tricyclic Antidepressants in the Overall Management of Fibromyalgia and Other Chronic Pain Syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1047–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Goldenberg D, Mayskiy M, Mossey C, Ruthazer R, Schmid C. A Randomized, Double-Blind Crossover Trial of Fluoxetine and Amitriptyline in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Athritis and Rheumatism. 1996;39(11):1852–1859. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Goldman RH, Stason WB, Park SK, Kim R, Schnyer RN, Davis RB, Legedza ATR, Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture for treatment of persistent arm pain due to repetitive use. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):211–218. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31815ec20f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hannonen P, Malminiemi K, Yli-Kerttula U, Isomeri R, Roponen P. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Moclobemide and Amitriptyline in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia in Females without Psychiatric Disorder. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.12.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kaptchuk TJ, Stason WB, Davis RB, Legedza ATR, Schnyer RN, Kerr CE, Stone DA, B.H. N, Kirsch I, Goldman RH. Sham device versus inert pill: a randomized controlled trial comparing two placebo treatments for arm pain due to repetitive use. Br Med J. 2006;332(7538):391–397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38726.603310.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lassen CF, Mikkelsen S, Kryger AI, Andersen JH. Risk factors for persistent elbow, forearm and hand pain among computer workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2005;31(2):122–131. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Levine DW, Simmons BP, Koris MJ, Daltroy LH, Hohl GG, Fossel AH, Katz JN. A self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1993;75A(11):1585–1592. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using general linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lynch ME. Anitdepressants as analgesics; a review of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26(1):30–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Magni G. The Use of Antidepressants in the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Drugs. 1991;42(5):730–748. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Max MB, Culnane M, Schafer SC, Gracely RH, Walther DJ, B. S, Dubner R. Amitriptyline relieves diabetic neuropathy pain in patients with normal or depressed mood. Neurology. 1987;37:589–596. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Max MB, Lynch SA, Muir J, Shoaf SE, Smoller B, Dubner R. Effects of Desipramine, Amitriptyline, and Fluoxetine on Pain in Diabetic Neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1250–1256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205073261904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McDowell I, Newell C. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [20].McQuay HJ, Carroll D, Glynn CJ. Dose-response for analgesic effect of amitriptyline in chronic pain. Anaesthesia. 1993;48:281–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].McQuay HJ, Tramer M, Nye BA, Caroll D, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. A systematic review of antidepressants in neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mico JAA, Denis, Berrocoso E, Eschalier A. Antidepressants and pain. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27(7):348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Repetitive Motion Disorders Information Page.

- [24].Ortiz-Hernandez L, Tamez-Gonzalez S, Martinez-Alcantara S, Mendez-Ramirez I. Computer use increases the risk of musculoskeletal disorders among newspaper office workers. Arch Med Res. 2003;34(4):331–342. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(03)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Piligian G, Herbert R, Hearns M, Dropkin J, Landsbergis P, Cherniack M. Evaluation and management of chronic work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the distal upper extremity. Am J Ind Med. 2000;37(1):75–93. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(200001)37:1<75::aid-ajim7>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pransky G, Feuerstein M, Himmelstein J, Katz JN, Vickers-Lahti M. Measuring functional outcomes in work-related upper extremity disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39(12):1195–1202. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199712000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement. 1977;1:387. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Reider B. The Orthopaedic Physical Examination. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Salerno SM, Browning R, Jackson JL. The effect of antidepressant treatment on chronic back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:19–24. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schlossberg EB, Morrow S, Llosa AE, Mamary E, Dietrich P, Rempel DM. Upper extremity pain and computer use among engineering graduate students. Am J Ind Med. 2004;46(3):297–303. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Staiger TO, Gaster B, Sullivan MD, Deyo RA. Systematic review of antidepressants in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Spine. 2003;28(22):2540–2545. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000092372.73527.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sudoh Y, Cahoon EE, Gerner P, Want GK. Tricyclic antidepressants as long-acting local anesethetics. Pain. 2003;103:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tittiranonda P, Rempel D, Armstrong TJ, Burastero S. Effect of Four Computer Keyboards in Computer Users With Upper Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders. Am J Ind Med. 1999;35:647–661. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199906)35:6<647::aid-ajim12>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Repetitive strain injury. Lancet. 2007;369:1815–1822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yassi A. Repetitive strain injuries. Lancet. 1997;349:943–947. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.