Abstract

Past research has linked physical activity and sports participation with improved mental and social well-being, including reduced risk of depression and suicidality. In this study we examined relationships among several dimensions of athletic involvement (team sport participation, individual sport participation, athlete identity, and jock identity), gender, and depression and suicidal behavior in a sample of 791 undergraduate students. Both participation in a team sport and athlete identity were associated with lower depression scores. Athlete identity was also associated with lower odds of a past-year suicide attempt, whereas jock identity was associated with elevated odds of a suicide attempt. The findings are discussed in light of the relationship between mental well-being and a larger constellation of health-risk behaviors linked to a “toxic jock” identity.

Past research has frequently linked physical activity and sports participation with improved mental and social well-being in young adults. These relationships are of interest because diagnoses of depression have grown increasingly common among U.S. college students in recent years (American College Health Association [ACHA], 2007), and many students experience symptoms of depression that go undiagnosed and untreated (Suicide Prevention Resource Center [SPRC], 2004). This trend is additionally disquieting because of the well-established link between depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior (Kisch, Leino, & Silverman, 2005). Although previous studies have identified regular physical exercise and/or athletic participation as protective against depression and suicidality, the mechanisms by which this protective effect operates—especially with respect to sports—are not well understood. The relationship between sport and mental health outcomes is further complicated by preliminary studies suggesting that different sport-related identities may have distinctly different implications for problem behavior (Miller, Sabo, Melnick, Farrell, & Barnes, 2006).

In common U.S. parlance, the label “jock” is often used as a slang or shorthand designation for “athlete,” frequently with uncomplimentary connotations. However, on closer examination, these two terms differ markedly in their cultural referents (e.g., the disciplined, overachieving “student-athlete” vs. the socially gregarious, ego-oriented “dumb jock”), gender associations, and implications for risky behavior, suggesting that they may in fact constitute two distinct if overlapping sport-related identities (Miller, in press; Miller, Sabo, et al., 2006). In this study, therefore, we have examined relationships among several dimensions of athletic involvement, gender, and depression and suicidal behavior, with particular attention to the roles of “athlete” identity and “jock” identity. Specifically, we used multivariate analyses of a sample of Western New York undergraduate students to test hypotheses that self-identification as an athlete would protect against both depression and likelihood of a suicide attempt whereas self-identification as a jock would exacerbate both outcomes. We further hypothesized that these relationships would be moderated by gender, with stronger effects for men than for women, and that sport-related identities would mediate the relationships between sports participation and depression and suicide. The following review of the extant literature on the links between depression/suicidality and exercise/sports activity, and the subsequent discussion of how an understanding of sport-related identities might inform such links, provide the context and rationale for these hypotheses.

Depression and Suicidality

Suicide is the third leading cause of death among U.S. adolescents and young adults today, comprising 12.9% of all deaths among 15- to 24-year-olds. Young men are at particularly high risk, with suicide completion rates more than six times those of their female peers. Most attempts do not result in death; the American Association of Suicidology estimates that only 1 in every 100–200 attempted youth suicides is completed. Young women are three times as likely as their male peers to experience an uncompleted suicide attempt (American Association of Suicidology [AAS], 2006; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control [NCIPC], 2007).

Though recurrent spotlighting by the popular media has problematized teen suicide in the public consciousness, college-age young adults are actually more likely to kill themselves; in 2004, the suicide rate for ages 20–24 was 12.5/100,000, compared with 8.2/100,000 for ages 15–19 (NCIPC, 2007). Controlling for age, college enrollment is actually associated with reduced suicidal behavior. With a completion rate of 7.5/100,000, college students are approximately half as likely to kill themselves as their nonstudent peers comparable in age, race, and gender (Silverman, Meyer, Sloane, Raffel, & Pratt, 1997). Viewed through the lens of Durkheim's classic theory of suicidality, this pattern would suggest that students are more tightly integrated into conventionally supportive social networks that reinforce prosocial norms and buffer them against the psychological consequences of social isolation and anomie (Durkheim, 1966 [1897]).

Though the links between depression and suicidality are widely recognized (e.g., Kisch et al., 2005; Konick & Gutierrez, 2005), far more students report symptoms of severe depression than are diagnosed and treated (SPRC, 2004). Two decades ago, Fehring, Brennan, and Keller (1987) estimated that one in six college students experienced depressive symptoms, half of them severe enough to require clinical intervention. The proportion of college students diagnosed with depression has increased markedly in recent years, from 10% in 2000 to 16% in 2005 (ACHA, 2007, 2006), potentially heralding an accompanying increase in suicidal ideation and/or behavior (Furr, Westefeld, McConnell, & Jenkins, 2001; Westefeld et al., 2006).

Linking Regular Exercise, Sports Activity, and Mental Well-Being

Research suggests a link between physical activity and mental health. In a meta-analysis of 37 research studies on the link between regular exercise and depressive and anxiety disorders, Dunn, Trivedi, and O'Neal (2001) concluded that exercise is associated with reduced depression and that the effect appears to be robust across levels (moderate vs. vigorous) and types of exercise (resistance vs. aerobic). However, the authors also decried the lack of randomized controlled trials to test for a dose-response relationship between levels of intensity, duration, and frequency of physical activity and levels of depression. A second meta-analysis of 14 studies (Lawlor & Hopker, 2001) reached a similarly cautious conclusion that, although frequent exercise appears to reduce symptoms of depression, widespread methodological weaknesses in the extant literature invites further high-quality research, particularly with respect to clinically depressed populations. A few studies have begun to fill this gap; for example, Simon, Powell, and Swann (2004) found that in a sample of Americans ages 13–34, those who made near-lethal suicide attempts were far less likely than controls to report exercising in the past month, a finding robust across levels of intensity, frequency, and duration of activity. However, it should be noted that the nature and universality of the link among regular exercise, depression, and suicidality remains in dispute (e.g., Galambos, Leadbeater, & Barker, 2004).

Mounting evidence suggests that the relationship between exercise and suicidality is conditioned by gender (Unger, 1997; Brown & Blanton, 2002). Where physical activity is generally associated with reduced depression and suicidal ideation for males, frequent exercise may signal an elevated suicide risk in their female counterparts, possibly due to links among negative body image, low self-esteem, depression, and suicidality. Unger (1997) identified frequent exercise (six or seven days a week) as a significant predictor of suicidal behavior in adolescent girls. Brown and Blanton (2002) similarly found that college women who were vigorously physically active every day or nearly every day had higher odds of suicidality than their less active peers. However, if depressed or suicidal women are disposed to use physical activity as a coping mechanism, findings by Ahmadi, Samavat, Sayyad, and Ghanizadeh (2002) suggest that the strategy may be to some degree successful; female college students scored significantly lower on the Beck Depression Inventory after embarking on a regular course of bodybuilding or swimming.

In contrast, while some uncertainty remains regarding the effects of regular exercise in general, a somewhat clearer pattern has emerged with respect to the links between suicidality and sports participation in particular. Involvement in organized sports places the individual within a complex social network characterized by regular interaction with peers, coaches, and health professionals; this engagement strengthens social bonds. Adolescents and young adults enmeshed in such a network may be less susceptible to the psychosocial consequences of anomie, defined by Durkheim (1897/1966) as a breakdown in social norms that leaves the individual alienated, socially and morally adrift, and at elevated risk for suicide. Compared with peers not involved in sports, athletes at the high school or college level generally report less frequent feelings of hopelessness (Baumert, Henderson, & Thompson, 1998), depression (Dishman et al., 2006; Gore, Farrell, & Gordon, 2001; Oler et al., 1994; Sanders, Field, Diego, & Kaplan, 2000), suicidal ideation (Harrison & Narayan, 2003; Oler et al., 1994; Sabo, Miller, Mel-nick, Farrell, & Barnes, 2005), and suicide attempts (Ferron, Narring, Cauderay, & Michaud, 1999; Harrison & Narayan, 2003; Oler et al., 1994; Page, Hammer-meister, Scanlan, & Gilbert, 1998), particularly suicide attempts by male adolescents (Tomori & Zalar, 2000; Unger, 1997). For example, Brown and Blanton (2002) found that participation on a college sports team significantly reduced students’ odds of seriously thinking about, planning, or attempting suicide; nonathlete men were 2.5 times as likely, and nonathlete women marginally more likely, to be suicidal than their athlete peers.

Notably, Choquet, Kovess, and Poutignat (1993) found no relationship between sports activities and suicidal ideation in 15- 18-year-old Quebecois or French adolescents. However, their single, undifferentiated sports measure (“very often engages in sports activities”) might well have obscured motivations to escape depression or body dissatisfaction via sport. Measures of this sort are also ill-equipped to distinguish between positive and negative athletic experiences, which may mediate the effects of low social acceptance and body dissatisfaction on adolescent depressive symptoms (Boone & Leadbeater, 2006). Choquet et al.'s study exemplifies a number of previous studies that have been hampered to some degree by cross-sectional designs (e.g., Brown & Blanton, 2002; Dishman et al., 2006) and/or crude, binary measures of athletics (Oler et al., 1994).

Although the potential for athletic involvement to complement other strategies for mental health promotion is increasingly recognized, coherent implementation of programs incorporating sport as a component of suicide prevention depends on a clearer understanding of connections as yet poorly understood. The links among sport, depression, and suicidality tend to be complex and conditional upon other factors such as gender (Sabo et al., 2005; Unger, 1997), peer and parental support (Gore et al., 2001; Kidd et al., 2006), or self-esteem (Dishman et al., 2006). Intensity or frequency of involvement also moderates the effects of sports participation. Page and his colleagues (1998) found that participants on one or two high school sports teams were less likely to attempt suicide than nonparticipants, but participation on three or more teams conferred no such protection. Similarly, Sanders et al. (2000) found that adolescents who devoted a moderate amount of time to sports (i.e., 3–6 hr/week) reported lower depression scores than those who spent less time, but those who invested more time in sports (7 or more hours/week) did not, a curvilinear relationship that the authors speculated might be due to the debilitating effects of overtraining. These studies suggest that excessive sports participation may actually cancel out the benefits associated with more moderate levels of participation. However, it is possible that these diminishing returns have less to do with how much or how often young people engage in sports than with how they interpret, contextualize, and assign meaning to the athletic experience; for example, an intense schedule of training and competition might be more isolating than sociable, or might heighten the conflict between prosocial norms (e.g., teamwork, fair play) and individualistic ones (e.g., winning at all costs).

Sport-Related Identities

Though a growing body of research has begun exploring links among sport, depression, and suicidality, these studies have generally employed objective measures of athletic participation, such as indicators of team membership or frequency of athletic activity. Yet the lived athletic experience includes a second, subjective dimension as well, in the form of sport-related psychosocial identities. With a few notable exceptions (e.g., Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, 2003; Miller, Farrell, Barnes, Melnick, & Sabo, 2005), very few studies have attempted to disaggregate the effects of objective sports participation (what one does) from the effects of subjective identity (what one feels and whom one is perceived to be, by oneself or others). Lantz and Schroeder (1999) have critiqued the widespread use of sport measures that fail to address the strength or exclusivity of the individual's identification with, or commitment to, the roles of “athlete” and/or “jock.” These terms have often been used interchangeably, but preliminary evidence suggests that the designations “athlete” and “jock” tap distinct if overlapping identities (Miller, in press).

The distinction between objective and subjective athletic involvement is important, because the overlap between dimensions is not absolute. For example, in one recent study, the correlation between frequency of athletic activity and identification with the label “jock” was only .31 overall; this correlation was significant for white but not black adolescents (Miller, Farrell, et al., 2005). Although the great majority of jocks participate in organized sports, Eccles and her colleagues found that a considerable proportion of sports participants identified more strongly with an alternative, non-sport-related identity (Barber, Eccles & Stone, 2001; Eccles & Barber, 1999). Furthermore, despite their overlap, athletic participation and sport-related identities may be associated with distinctly different profiles with respect to problem behaviors. In a series of analyses of adolescent problem behaviors, we have identified an emergent pattern: whereas sports activity tends to correlate with more salutary behavioral outcomes, self-reported “jock” identity correlates with less desirable outcomes with respect to problem drinking (Miller et al., 2003), sexual risk taking (Miller, Farrell, et al., 2005), academic misconduct (Miller, Melnick, Barnes, Farrell, & Sabo, 2005), interpersonal violence (Miller, Melnick, Farrell, Sabo, & Barnes, 2006), and delinquency (Miller, Melnick, Barnes, Sabo, & Farrell, 2007). However, none of those analyses assessed relationships between problem behaviors and self-reported “athlete” identity.

Though differing outcomes associated with objective vs. subjective athletic measures clearly indicate the tapping of distinct, if overlapping, constructs, to date there has been little focus on disaggregating their effects. Even less attention has been devoted to the partitioning of deceptively similar sport-related identities that appear synonymous on the surface yet may have distinctly different implications for health-risk outcomes. For example, in the above analyses, we contrasted sports participation with only one sport-related identity (“jock”). Empirical evidence regarding jock/athlete differences remains sparse and largely anecdotal. No previous study has disaggregated the effects of sports participation, athlete identity, and jock identity.

However, in a recent focus group study of undergraduate college student-athletes, discussants identified several key differences between jocks and athletes (Miller, Sabo, et al., 2006). Most notably, an athlete identity was associated with academic commitment and performance, whereas jocks were perceived as deemphasizing academics and in many instances receiving special assistance or privileges designed to overcome scholastic shortcomings; athletes emphasized teamwork and collective achievement, whereas jocks emphasized self-promotion and glory seeking; and while both athletes and jocks were likely to be popular, jocks were also perceived through twin lenses of vanity and bullying. While any sport might produce an athlete identity, only a handful of high-profile sports with significant physical contact and rich in “masculine” imagery were likely to generate a jock identity.

Sport-related identities may differ markedly in terms of how they evoke the contemporary gender order. Connell (2005) introduced the concept of “hegemonic masculinity” to signify an aspirational, culturally exalted version of ideal masculinity as broadly defined within mainstream U.S. culture. While multiple masculinities exist, and the hegemonic ideal is always subject to ongoing negotiation, this core set of largely uncontested prescriptive norms and body practices occupies a prominent and privileged position in a broadly accepted, contemporary U.S. gender hierarchy (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). As a strategy for perpetuating that hierarchy (Demetriou, 2001), hegemonically masculine beliefs and practices have the ironic effect of undermining the health and well-being of those whose dominance they protect (Courtenay, 2000). For example, the norms associated with high-status, high-profile U.S. sports (most notably, male body-contact sports such as football) may compromise health by promoting violence and discouraging self-regard for injuries (Messner & Sabo, 1990; Messner, 1992). However, not all sport subcultures or identities are equally enmeshed in this version of masculinity. In one study of Western New York undergraduate students, self-reported jock identity was characterized by broad conformity to conventionally masculine normative approaches to violence, domination, risk taking, and sexual promiscuity. In contrast, self-identified “athletes” did not endorse any of these norms. In fact, the only point of normative agreement between jocks and athletes was a strong emphasis on winning (Miller, in press). Thus the linkage among athletic involvement, gender practice, and health consequences is likely contingent upon sport-related identity. To the extent that a culturally dominant masculine ethic is perceived to be at odds with admitting or seeking treatment for suicidal ideation and behavior (Connell, 2005; Courtenay, 2000; Emslie, Ridge, Ziebland, & Hunt, 2006), jock identity—but not athlete identity—may be theorized as a risk factor for suicidality.

Another key distinction between athletes and jocks may lie in the extent to which each identity reflects and/or promotes integration within a conventional prosocial network revolving around sports participation. This distinction may have health-related implications when considered in light of Durkheim's (1897/1966) classic thesis that social integration is associated with a reduced risk of suicide. With their greater emphasis on teamwork and commitment to the school, athletes may be better protected against the mental health consequences of poor social integration than jocks.

Hypotheses

If different sport-related identities derive from different experiences and generate different characteristic profiles, it is reasonable to infer that they are likely to differ in their mental health implications as well. We suggest that the negative relationship between sports activity and depression and suicidality derives in part from the development of an athlete identity, whereas the development of a jock identity will have less salutary associations. We have accordingly drawn on the qualitative focus-group insights of college sports participants (Miller, Sabo, et al., 2006) as well as quantitative findings regarding the differences between jocks and athletes (e.g., Miller, in press) to generate the following four hypotheses about the relationships among sports participation, sport-related identities, gender, depression, and suicidal behavior. Specifically, we hypothesize that (1) Strength of athlete identity will be inversely related to depression and to likelihood of a suicide attempt; (2) Strength of jock identity will be directly related to depression and to likelihood of a suicide attempt; (3) The relationships between individual and team sport participation and depression and suicide attempts will be mediated by sport-related identities; and (4) The relationships between sport-related identity and depression will be moderated by gender. Because of its strong association with conventionally masculine imagery, jock identity will more effectively predict depression for men than for women.

Methods

Data

The 2006 Athletic Involvement Study was conducted to develop comprehensive measures of athletic involvement and to examine links among athletic involvement, gender norms, and adolescent/young adult health risks, including substance use, unsafe sex, and other high-risk behaviors. Undergraduate college students enrolled in large-section Sociology, Communications, and Economics courses at a large Northeastern university completed a 45-minute anonymous questionnaire. Each participant received $10.00 compensation. In the case of the Communications students, the study also counted for research credit that could be applied toward fulfillment of a course requirement. Of the approximately 1500 students invited to participate in the study, 791 submitted viable questionnaires, for an approximate response rate of 53%. (An exact response rate could not be calculated due to overlapping course enrollments by some students.).

Dependent Measures

Depression

Depression was measured using a 10-item abbreviated version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977, 1991). Respondents were asked to rate the frequency of ten symptoms experienced in the past week, including how often they “were bothered by things that don’t usually bother me,” “had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing,” “felt like everything was an effort,” or “could not get going”; had feelings of hopelessness, fear, loneliness, or unhappiness; or experienced loss of energy or difficulty sleeping. Responses for each item ranged from 1 (“rarely or none of the time”) to 4 (“all of the time”). The alpha reliability score for the depression scale was .82.

Suicide attempt

Respondents were also asked if they had tried to commit suicide at any time in the past year, with responses coded dichotomously (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Independent Measures

Sport-related identities

To measure sport-related identities, subjects were asked to respond to a series of self-evaluative statements, with 5-point response ranges from “strongly disagree” (= 1) to “strongly agree” (= 5). Strength of jock identity was assessed with the statement: “I tend to see myself as a jock.” A parallel statement, “I tend to see myself as an athlete,” assessed strength of athlete identity. Because jock and athlete identities were conceptualized as overlapping rather than mutually exclusive, these two measures were scored independently of each other.

Continuous measures such as these provide inherently more information about strength of identity than dichotomous measures; therefore, the continuous “strength of identity” measures were used in all multivariate analyses. However, it is intuitively easier to compare discrete high/low categories. For use in descriptive comparisons only, then, the continuous jock identity and athlete identity measures were also dichotomized so that respondents scoring 4 (agree) or 5 (strongly agree) were distinguished from those scoring 3 or lower (neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree). Respondents who scored high on jock identity were designated “jocks” and those who scored high on athlete identity were designated “athletes.” Again, because these measures were scored independently, the categories of “jock” and “athlete” were not mutually exclusive; in fact, there was considerable overlap between the two.

Perceptions of sport-related identities

No operational definitions of “jock” or “athlete” were supplied to subjects, who were left to interpret these terms for themselves. However, some insight into the prevailing definitions may be derived from subject ratings of overall jock and athlete characteristics. The Jock/Athlete Characteristic Inventory (JACI) lists a series of descriptive characteristics, such as “plays fair,” “parties a lot,” “talented,” and “bully.” On a response continuum from 1 (“doesn't describe at all”) to 5 (“describes extremely well”), respondents were asked to assess how closely they thought each of these characteristics described jocks and how closely they thought it described athletes. To confirm that subjects in the Athletic Involvement Study sample broadly endorsed the conceptual distinctions between these two sport-related identities we have identified here, we compared subject rankings on selected characteristics. A mean score on six items related to prosocial norms (“good team player,” “plays fair,” “works/practices hard,” “self-disciplined,” “careful to follow the rules,” and “good role model”) was calculated to construct an index of Prosocial characteristics (Cronbach's alpha for jocks = .75, alpha for athletes = .82). The six-item Risky Masculinity index included the items “tough,” “handles pain well,” “risk-taker,” “macho,” “win by any means necessary,” and “sexually aggressive” (jock alpha = .83, athlete alpha = .70). Susceptibility to Substance Use included “drinks a lot,” “parties a lot,” “likely to binge drink,” and “likely to use steroids” (jock alpha = .84, athlete alpha = .79). Finally, the gender flexibility of each identity was assessed with a single JACI measure, “could be female.”

Individual and team sports participation

To permit distinctions between sport-related identity and sport-related activity, we included two dichotomous measures of recent sports participation. Respondents were provided with a list and asked to identify any school or community sports in which they had participated in the past year. Listed sports were subsequently divided into two categories. Team sports (requiring two or more people on the same side to coordinate their movements) included baseball, cheerleading, dance, field hockey, football, ice hockey, lacrosse, rugby, soccer, softball, and volleyball. Individual sports (requiring no coordination, though scores may be aggregated across individuals) included boxing, bowling, cross country, golf, gymnastics, martial arts, skiing, swimming/diving, tennis, track/field, and wrestling. Approximately 31% reported participating in at least one team sport. Individual sports participation was less common; 9% reported participating in at least one such sport. While these two categories were not mutually exclusive, most students restricted their involvement to one or the other; of the 285 respondents who participated in any sport in the past year, 74% engaged in a team sport only, 14% engaged in an individual sport only, and 12% engaged in both.

Sociodemographic measures

Data were collected on gender (male = 0; female = 1), age, race, parental educational attainment, and college grade point average (GPA). After preliminary analysis, responses to a multicategory, self-referential question on race were collapsed into a dichotomous measure (0 = white, 1 = non-white) to generate large enough cell sizes for optimal hypothesis testing. Parental educational attainment was included as a proxy for social class. Students were asked to identify each parent's highest level of education from among five options: did not finish high school (coded as 10 years); high school degree or GED (12 years); some college or technical certification (14 years); bachelor's degree (16 years); and postgraduate or professional degree, e.g., MA, MBA, PhD, or MD (18 years). Parental educational attainment was coded as the higher available response if mother's and father's education levels differed, or if the respondent provided data for only one parent. Cases where neither parent's educational history was available (n = 14) were recoded to the whole-sample mean of 15.37 years. College GPA was measured on a 4.00 scale, by respondent self-report.

Analyses

To assess perceptions about the typical characteristics associated with jocks vs. athletes, we conducted Wilcoxon signed-rank tests of selected JACI characteristics related to prosocial norms, risky masculine norms, susceptibility to substance use, and gender. These nonparametric tests compare the distributions of two related variables and are a more appropriate mechanism for comparing ordinal variables than t tests, which require interval-level data. JACI scores were also compared by gender, using one-way ANOVAs to check for significant mean differences on the perceptions of female and male subjects.

To test hypotheses regarding the relationships among sport-related identities, gender, depression, and suicidality, we conducted a series of multivariate analyses. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were used to predict CES-D depression scores. Because the measure of suicidal behavior was dichotomous, the effect of sport-related identities on college student suicide attempts was examined using logistic regression analysis. In both instances, we controlled for gender, age, race, parental education, college GPA, and recent individual and team sports participation.

Several follow-up analyses were conducted to explore the nuances of the relationships among athletic involvement, gender, and depression. First, product terms were entered into the regression to test for gender interactions that would justify separate follow-up analyses for women and for men. Significant interactions were probed by follow-up with separate, gender-specific analyses. Second, mediation analyses were performed to examine whether either jock identity or athlete identity mediates the relationships between individual or team sports participation and depression and suicide attempts. Where conditions for mediation were met, the significance of the findings was assessed via posthoc application of the Sobel test (Frazier, Tix, & Barron, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, in press).

Results

Table 1 presents both overall and gender-specific descriptive statistics for the Athletic Involvement Study sample. Of the 791 valid respondents, 48% identified themselves as female, and the average age was 20. Students of color were over-represented, with nonwhites comprising a third of the sample, compared with approximately 20% of the overall undergraduate population. The mean level of parental education was 15.37 years, indicating at least some college experience. Women's mean GPA (3.06) significantly exceeded men's GPA (2.86), but men scored higher on three of the four sport-related measures; 40% of men had participated on a school or community sports team in the past year, compared with 20% of women, and men indicated significantly stronger identification as both jocks and athletes. Depression scores were normally distributed, and neither depression (mean score 1.97 on a 1–4 scale) nor past-year suicide attempts (3% of respondents) differed by gender.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics by Gender

| All (N = 791) | Females (n = 374) | Males (n = 416) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | |||

| female (= 1) | .48 | — | — |

| age | 20.02 | 19.94 | 20.09 |

| nonwhite (= 1) | .34 | .33 | .35 |

| parental education, in years | 15.37 | 15.30 | 15.43 |

| college GPA (0.00–4.00) | 2.95 | 3.06 | 2.86* |

| individual sport participation (= 1) | .09 | .09 | .10* |

| team sport participation (= 1) | .31 | .20 | .40 |

| Sport-related identities | |||

| athlete identity (low = 1, high = 5) | 3.02 | 2.55 | 3.43* |

| jock identity (low = 1, high = 5) | 2.00 | 1.67 | 2.30* |

| Mental well-being | |||

| depression scale (low = 1, high = 4) | 1.97 | 1.98 | 1.96 |

| suicide attempt, past year (= 1) | .03 | .03 | .02 |

Note: Sample total does not equal sum of female and male subsamples because one respondent did not provide information on gender.

p < .001.

Prosocial, Risky Masculinity, Substance Use, and Gender JACI scores assigned to athletes and to jocks by the sample as a whole showed clear differences in perceptions about these sport-related identities (data not shown in tabular form). Prosocial characteristics (i.e., good team player, plays fair, works/practices hard, self-disciplined, careful to follow the rules, good role model) were collectively perceived as more descriptive of athletes than jocks (athlete mean = 4.18, jock mean = 2.86; Wilcoxon Z = –22.65, p < .001). In contrast, Risky Masculinity characteristics (i.e., tough, handles pain well, risk taker, macho, win by any means necessary, sexually aggressive) were collectively perceived as more descriptive of jocks than athletes (jock mean = 4.07, athlete mean = 3.41; Wilcoxon Z = –17.59, p < .001), as were characteristics related to Susceptibility to Substance Use (i.e., drinks a lot, parties a lot, likely to binge drink, likely to use steroids; jock mean = 4.14, athlete mean = 2.63; Wilcoxon Z = –21.92, p < .001). The single Gender item, “could be female,” received a significantly higher ranking as a descriptor of athletes than of jocks (athlete mean = 4.41, jock mean = 2.96; Wilcoxon Z = –18.40, p < .001). These findings, while not definitive, are consistent with an interpretation that situates athlete identity within the context of a prosocial network, while situating jock identity within the context of a brand of masculinity that marries sport with risk taking.

Between-gender comparisons showed no significant differences in how females and males perceived the characteristics of jocks. However, female subjects assigned significantly higher Prosocial and Gender scores, and lower Risky Masculinity scores, to athletes than their male counterparts did. These findings may indicate a somewhat greater tendency for women to distinguish between the two sport-related identities, possibly because one (athlete) is perceived as more accessible to women than the other (jock).

Though the sport-related identities of “athlete” and “jock” overlap considerably (correlation coefficient = .62, p < .01), most students personally embraced the identity of athlete more strongly; this outcome was unsurprising, in light of the broad tendency to attribute more conventionally desirable JACI traits to athletes and less desirable JACI traits to jocks. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics by sport-related identity, where for comparison purposes each identity has been dichotomized. Only 12% of respondents met the “jock” criterion (scoring 4 or 5 on the applicable 1–5 identity scale), whereas 43% could be similarly classified as “athletes.” Jocks were more likely than nonjocks to be male and to report team sport participation; however, jock identity did not significantly predict participation in an individual sport. In contrast, athletes were significantly higher than nonathletes in socioeconomic status (i.e., parental education), less likely to be nonwhite or female, and more likely to participate in both individual and team sports. Most notably, athletes scored significantly lower than nonathletes on the depression scale.

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics by Sport-Related Identities

| Nonathletes (n = 448) | Athletes (n = 343) | Nonjocks (n = 699) | Jocks (n = 92) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | ||||

| female (= 1) | .59 | .32*** | .51 | .22*** |

| age | 20.06 | 19.95 | 20.01 | 20.04 |

| nonwhite (= 1) | .39 | .27*** | .35 | .26† |

| parental education, in years | 15.15 | 15.69** | 15.38 | 15.46 |

| college GPA (0.00–4.00) | 2.95 | 2.97 | 2.97 | 2.86† |

| individual sport participation (= 1) | .06 | .13** | .09 | .12 |

| team sport participation (= 1) | .13 | .55*** | .27 | .64*** |

| Sport-related identities | ||||

| athlete identity (low = 1, high = 5) | — | — | 2.82 | 4.51*** |

| jock identity (low = 1, high = 5) | 1.49 | 2.67*** | — | — |

| Mental well-being | ||||

| depression scale (low = 1, high = 4) | 2.05 | 1.87*** | 1.98 | 1.89 |

| suicide attempt, past year (= 1) | .03 | .02 | .02 | .05 |

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .10.

To assess the relationships between sport-related identities and depression net of the effects of gender, age, race, social background, and individual and team sports participation, we conducted three multiple regression analyses (Table 3). In Model One, which excludes sport-related identities, both college GPA and team (but not individual) sport participation were associated with lower depression scores. As shown in Model Two, however, the effect of objective team sport participation ceased to be statistically significant when athlete (but not jock) identity was included in the equation. The Model Three analysis including product terms for gender and each of the four sport-related measures uncovered a significant interaction between gender and participation in an individual sport. In separate, exploratory gender-specific regressions (data not shown), we found that both individual sport participation (β = –.10, p < .05) and athlete identity (β = –.18, p < .01) were inversely related to depression in a male-only model but not in a female-only model, suggesting that the salutary effects of both objective and subjective athletic involvement may be a largely male phenomenon.

Table 3.

Regressions Predicting College Student Depression (N = 737)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | β | R2 | β | R2 | β | R2 |

| .04 | .05 | .06 | ||||

| Female | .01 | –.02 | –.08 | |||

| Age | .02 | .01 | .01 | |||

| Nonwhite | .07† | .06 | .06 | |||

| Parental education | –.04 | –.04 | –.04 | |||

| College GPA | –.08* | –.08* | –.09* | |||

| Individual sport participation | –.03 | –.03 | –.10+ | |||

| Team sport participation | –.12** | –.07† | –.08 | |||

| Athlete identity | –.14** | –.19** | ||||

| Jock identity | .05 | .08 | ||||

| Female × individual sport | .11* | |||||

| Female × team sport | –.00 | |||||

| Female × athlete identity | .12 | |||||

| Female × jock identity | –.07 | |||||

Note: Sample N was 723 because of missing responses for the depression variable.

p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .10.

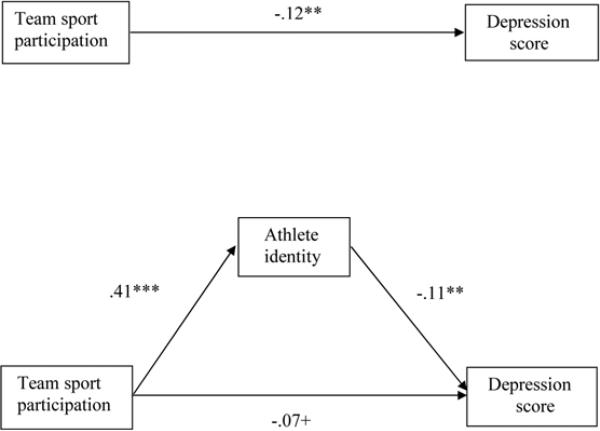

It was hypothesized that both jock identity and athlete identity would mediate the relationships between individual and team sports participation and depression. To demonstrate mediation, it is necessary to satisfy four conditions: (1) that the independent variable (IV) significantly predicts the dependent variable (DV); (2) that the proposed mediator (M) significantly predicts the DV; (3) that the association between the DV and the IV is significantly reduced when M is added to the equation; and (4) that the IV significantly predicts M (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The analyses shown in Table 3 satisfied the first three of these conditions with respect to athlete identity. The fourth condition was satisfied in a supplemental analysis showing that team sports participation predicted strength of athlete identity (R2 = .30, β = .41, F(7,779) = 173.42, p < .001). Finally, the Sobel test was performed to assess whether the addition of the mediator to the equation had a significant effect on the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. This test confirmed that strength of athlete identity fully mediated the relationship between team sports participation and depression (z = –2.72, p < .01; See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mediation of relationship between team sport participation and depression by strength of athlete identity. Note. Sobel z = –2.72**. ***p < .001. **p < .01. *p < .05. +p < .10.

Table 4 presents results of a hierarchical series of logistic regressions predicting college student suicide attempts, controlling for gender, age, race, parental education, maternal employment, college GPA, and past-year sports team participation. Contrary to prior studies (e.g., Brown & Blanton, 2002; Ferron et al., 1999; Harrison & Narayan, 2003; Oler et al., 1994; Page et al., 1998), sports team participation did not buffer against attempted suicide (Model One). However, athlete identity was significantly associated with reduced odds of a suicide attempt, whereas jock identity was actually associated with increased odds of the same (Model Two). Because Model Three showed no significant gender interactions, separate gender-specific logistic regression analyses for females and for males were not conducted. Nor were the necessary criteria met to demonstrate that either jock or athlete identity mediated the relationship between sports team participation and suicide attempts, since sports team membership did not significantly predict suicidality.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logistic Regressions Predicting College Student Suicide Attempts: Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals (N = 786)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Female | 1.92 | (.74–4.98) | 1.93 | (.70–5.28) |

| Age | .93 | (.71–1.24) | .93 | (.70–1.24) |

| Nonwhite | .97 | (.36–2.59) | .81 | (.30–2.19) |

| Parental education | .98 | (.80–1.20) | .98 | (.80–1.21) |

| College GPA | .49† | (.22–1.08) | .52 | (.23–1.17) |

| Individual sport participation | .46 | (.06–3.56) | .51 | (.07–3.99) |

| Team sport participation | 2.29† | (.89–5.91) | 2.81† | (.92–8.57) |

| Athlete identity | .54* | (.32–.93) | ||

| Jock identity | 1.98* | (1.14–3.45) | ||

| –2 Log Likelihood | 179.46 | 172.22 | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | .04 | .08 | ||

p < .05.

p < .10.

Discussion

Past findings have repeatedly pointed to a complex and contradictory relationship among athletic involvement, gender, depression, and suicidality. Though various researchers have illuminated aspects of this relationship, including its inconsistencies, none have sought to explain these inconsistencies by disaggregating elements of the athletic experience. If there is a core insight to be derived from the current study, it is that athletic involvement is not monolithic in nature. In other words, objective measures of athletic participation cannot encapsulate the underlying commitment to a sport-related identity; nor are all sport-related identities alike in their antecedents or their implications.

Parallel images of sport have long dominated public discourse and popular imagery. The disciplined Olympic gold medalist and the high school bully clad in a varsity letter jacket (a recurrent character in decades of U.S. teen movies) may share a common interest in sports, but they manifestly do not evoke the same aesthetic. It is no great stretch of the imagination to find that these images, cartoonish in their extremity, nevertheless reflect—in however distorted a fashion—a fundamental underlying reality of the athletic experience. That is, sports participants and enthusiasts vary widely in the structure and subjective content of their athletic involvement, leading to the development of categorically different sport-related identities with measurably different characteristics and implications for mental well-being and associated health-risk outcomes such as depression and suicidality. Our findings in the present analysis support that contention, with respect to both the perceived differences between athletes and jocks (i.e., our JACI findings) and the relationships between sport-related self-identification and depression/suicidal behavior outcomes.

In this study, we hypothesized that (1) strength of athlete identity would be inversely related to both depression and odds of a suicide attempt, whereas (2) strength of jock identity would be directly related to both outcomes, (3) both sport-related identities would mediate the relationships between team sports participation and depression and suicide attempts, and (4) these relationships would be moderated by gender, with stronger effects of jock identity for men than for women. Our findings were moderately supportive of the first three hypotheses. Athlete identity was significantly negatively associated with both depression and suicidal behavior. Nor can athlete identity be dismissed as merely symptomatic of objective athletic activity. As demonstrated in Table 3, team sports participation was associated with lower rates of depression, but the significance disappeared when sport-related identities were added to the equation. Specifically, athlete identity mediated the relationship between team sport participation and depression (Figure 1). It must be remembered that the cross-sectional nature of the data does not permit conclusions regarding the causal directions of these relationships. However, this finding is at least consistent with the interpretation that the experience of playing on a team may contribute to the development of a prosocial athlete identity that in turn buffers against depression. Notably, jock identity had no such mediating effect.

Although jock identity did not significantly predict depression scores, it was positively associated with elevated odds of a suicide attempt. Given that this finding is at odds with the bulk of extant research on sports participation and suicidality (Brown & Blanton, 2002; Ferron et al., 1999; Harrison & Narayan, 2003; Oler et al., 1994; Sabo et al., 2005; Page et al., 1998), it is clear that jock identity is not reducible to a side effect of objective athletic activity either. The nature of the modest but statistically significant association between jock identity and suicide risk calls for closer examination.

The hypothesis regarding gender moderation was not supported, owing to the lack of statistically significant gender interactions in whole-sample analyses. This somewhat surprising finding must be interpreted with caution. It may be to some extent artifactual, deriving from the atypical similarity in overall depression scores in women and men in our sample. Although it has been widely documented that women suffer from higher rates of depression than men (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, 1990; Piccinelli & Wilkinson, 2000), we found no gender difference in unadjusted mean CES-D scores. However, in separate gender-specific equations, jock identity significantly predicted lower rates of depression for men but not for women. Coupled with previous studies that identified different sport/suicidality dynamics for female and male adolescents (e.g., Sabo et al., 2005; Unger, 1997), these exploratory analyses were at least indicative of potential gender differences in the link between sport-related identities and depression that might fruitfully be explored by future researchers.

Identifying empirical differences in outcomes associated with athlete and jock identities is a more straightforward enterprise than explaining those differences. The cross-sectional data used in these analyses did not permit us to test for causal relationships, so our interpretations must remain speculative. Building on the as-yet unproven supposition that the links between sport-related identities and suicidality are in some part causal rather than merely correlative, though, what is it about being an “athlete” that might enhance mental and social well-being or otherwise buffer against health-compromising behaviors? There is most likely more to the dynamic than the salutary effects of regular exercise alone, since young adults with strong athlete identities report significantly lower depression scores (Table 2) even after controlling for both individual and team sport participation (Table 3). To the extent that such an identity is associated with prosocial, culturally approved characteristics such as teamwork and academic achievement (Miller, Sabo, et al., 2006), it may be representative of both a broad adherence to conventional norms and participation in a sport-related social network that together provide some protection from depression and suicidality.

In contrast, our past studies have shown that a strong jock identity is more likely to be a red flag for a variety of problem behaviors (Miller et al., 2003; Miller, Farrell, et al., 2005; Miller, Melnick, et al., 2005; Miller, Melnick, et al., 2006; Miller, Melnick, et al., 2007). Moreover, this identity appears to owe some of its impetus to hegemonic masculinity, which in contemporary U.S. culture includes imperatives regarding violence, risk-taking, stoicism in the face of pain or injury, and an assortment of other potentially health-compromising behaviors (e.g., Connell, 2001; Messner & Sabo, 1990; Weinstein, Smith, & Wiesenthal, 1995). Collectively, these findings raise the specter of a “toxic jock” identity that marries sports involvement to a broadly self-destructive worldview and set of normative expectations for behavior (Miller, in press). Further consistent with this supposition, our JACI findings reveal a perceptual equation between a jock identity and a brand of masculinity that emphasize risk-taking, including some degree of tolerance for health-compromising behaviors such as substance use and sexual aggression.

At first glance, it seems unlikely that the outcomes of interest in the current study would fit into this constellation of “masculine” health risks. Depression, classified as an internalizing rather than externalizing disorder (Leadbeater, Blatt, & Quinlan, 1995; Leadbeater, Kuperminc, Blatt, & Hertzog, 1999), and attempted suicide are both disproportionately seen in women (AAS, 2006). However, upon finding that sports participation—while decreasing the odds of suicidal ideation in female adolescents—was associated with an increased likelihood of serious self-injury in suicidal male adolescents, Sabo and his colleagues (2005) speculated that under some circumstances athletic norms might actually facilitate such injury by inuring already-suicidal teens against pain-related inhibitions. In keeping with this interpretation, which is consistent with the parameters of hegemonic masculinity, it may be that jock identity facilitates not suicidality per se but rather the likelihood of acting affirmatively on suicidal ideation and lethality of the outcome, a distinction our dichotomous “suicide attempt” measure was not designed to address.

Limitations of the Study and Directions for Future Research

As with most research studies, the nature of our data limited the conclusions that could safely be drawn. The sample was drawn from students at a single regional university, limiting its national or crossnational generalizability; moreover, although the courses whose enrollments were sampled generally served a broad range of students seeking to fill general electives, it is possible that a sample drawn from more specialized courses (e.g., physical education or sport sciences) would have yielded different findings. Slightly more than half of the students sent invitations to participate in this study responded by submitting a viable questionnaire; although the demographics of the sample closely resembled the overall student population except for a disproportionately high response rate by African Americans, self-selection bias may have distorted our results in unforeseen ways. These data were also cross-sectional, permitting us to identify associations but not causal relationships. It remains to be seen in future studies whether athletic involvement does indeed affect psychological well-being and risk for suicidality, or whether the relationship is in fact reversed, reciprocal, or even spurious. Our measures of athlete and jock identity were self-referential, lacking peer confirmation, and we could not rule out the possibility that these identities held different meanings for women and for men. Therefore, potential ambiguity in subject interpretations of our measures may have undermined their validity to some extent, although the JACI findings regarding perceived jock/athlete characteristic differences provide some reassurance in this respect. Finally, to accommodate the limited available space in our survey instrument, our single measure of suicidal behavior did not include other key aspects of suicidality such as suicidal ideation, degree of lethality, or frequency of suicide attempts. Collectively, the lack of refinement in our measures may have further suppressed the already low variance in depression/suicidal behavior explained by our analyses.

Despite these limitations, the current study has broken new ground in our understanding of the nexus of sport and mental health outcomes by introducing two previously unexamined avenues of inquiry: differences between objective and subjective athletic involvement, and differences between distinct sport-related identities. We have posited the emergence of a “toxic jock” identity, particularly for young men, which may impact on the likelihood of engaging in a constellation of health-risk behaviors. Primary testing of this construct involved multivariate analyses of survey data, but its evolution was informed by in-depth focus group interviews that provided insight into the subjective perceptions of sport-involved young people themselves. Future studies should likewise draw upon both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, marrying empirical rigor and interpretive nuance to capture the richness and variation of sport-related identities and their implications. Most importantly, longitudinal studies will be needed to better assess whether a toxic jock identity exists—and, if so, whether it has a causal effect of its own or is merely an outgrowth of other distal causes of problem behavior.

References

- Ahmadi J, Samavat F, Sayyad M, Ghanizadeh A. Various types of exercise and scores on the Beck depression inventory. Psychological Reports. 2002;90:821–822. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2002.90.3.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association American College Health Association national college health assessment (ACHA-NCHA) spring 2005 reference group data report (abridged). Journal of American College Health. 2006;55:5–16. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.1.5-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association American College Health Association National college health assessment spring 2006 reference group data report (abridged). Journal of American College Health. 2007;55:195–206. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.4.195-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Suicidology [March 26, 2007];Youth suicide fact sheet. 2006 ( http://www.suicidology.org/associations/1045/files/Youth2003.pdf)

- Barber BL, Eccles JS, Stone MR. Whatever happened to the jock, the brain, and the princess? Young adult pathways linked to adolescent activity involvement and social identity. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16:429–455. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumert PW, Jr., Henderson JM, Thompson NJ. Health risk behaviors of adolescent participants in organized sports. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;22:460–465. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone EM, Leadbeater BJ. Game on: Diminishing risks for depressive symptoms in early adolescence through positive involvement in team sports. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Blanton CJ. Physical activity, sports participation, and suicidal behavior among college students. Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise. 2002;34:1087–1096. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet M, Kovess V, Poutignat N. Suicidal thoughts among adolescents: an intercultural approach. Adolescence. 1993;28:649–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Studying men and masculinity. Resources for Feminist Research. 2001;29:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. 2nd ed. Polity Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt J. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society. 2005;19:829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou DZ. Connell's concept of hegemonic masculinity: A critique. Theory and Society. 2001;30:337–361. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Hales DP, Pfeiffer KA, Felton G, Saunders R, Ward DS, et al. Physical self-concept and self-esteem mediate cross-sectional relations of physical activity and sport participation with depression symptoms among adolescent girls. Health Psychology. 2006;25:396–407. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O'Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Medicine & Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001;33:S587–S597. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. In: Suicide: A study in sociology. Spaulding JA, Simpson G, editors. Free Press; New York: 1897/1966. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber BL. Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:10–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber BL, Stone M, Hunt J. Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59:865–889. [Google Scholar]

- Emslie C, Ridge D, Ziebland S, Hunt K. Men's accounts of depression: Reconstructing or resisting hegemonic masculinity? Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:2246–2257. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring RJ, Brennan PF, Keller ML. Psychological and spiritual well-being in college students. Research in Nursing & Health. 1987;10:391–398. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron C, Narring F, Cauderay M, Michaud P-A. Sport activity in adolescence: Associations with health perceptions and experimental behaviours. Health Education Research. 1999;14:225–233. doi: 10.1093/her/14.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Furr SR, Westefeld JS, McConnell GN, Jenkins JM. Suicide and depression among college students: A decade later. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2001;32:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Leadbeater BJ, Barker ET. Gender differences in and risk factors for depression in adolescence: A 4-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Farrell F, Gordon J. Sports involvement as protection against depressed mood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison P, Narayan G. Differences in behavior, psychological factors, and environmental factors associated with participation in school sports and other activities in adolescence. Journal of School Health. 2003;73:113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2003.tb03585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S, Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Davidson L, King RA, Shahar G. The social context of adolescent suicide attempts: Interactive effects of parent, peer, and school social relations. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36:386–395. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisch J, Leino EV, Silverman MM. Aspects of suicidal behavior, depression, and treatment in college students: Results from the spring 2000 National College Health Assessment Survey. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:3–13. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.1.3.59263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konick LC, Gutierrez PM. Testing a model of suicide ideation in college students. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:181–192. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.2.181.62875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz CD, Schroeder PJ. Endorsement of masculine and feminine gender roles: Differences between participation in and identification with the athletic role. Journal of Sport Behavior. 1999;22:545–557. [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, Hopker SW. The effectiveness of exercise as an intervention in the management of depression: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:763–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Blatt SJ, Quinlan DM. Gender-linked vulnerabilities to depressive symptoms, stress, and problem behaviors in adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater B, Kuperminc G, Blatt S, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1268–1282. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner MA. Power at play: Sports and the problem of masculinity. Beacon; Boston: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Messner MA, Sabo DF, editors. Sport, men, and the gender order. Human Kinetics; Champaign, IL: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE. Sport-related identities and the ‘toxic jock.’. Journal of Sport Behavior. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Farrell MP, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ, Sabo D. Gender/racial differences in jock identity, dating, and adolescent sexual risk. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:123–136. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-3211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Hoffman JH, Barnes GM, Farrell MP, Sabo D, Melnick MJ. Jocks, gender, race, and adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:445–462. doi: 10.2190/XPV5-JD5L-RYLK-UMJA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Melnick MJ, Barnes GM, Farrell MP, Sabo D. Untangling the links among athletic involvement, gender, race, and adolescent academic outcomes. Sociology of Sport Journal. 2005;22:178–193. doi: 10.1123/ssj.22.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Melnick MJ, Barnes GM, Sabo D, Farrell MP. Athletic involvement and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:711–723. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9123-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP, Sabo D, Barnes GM. Jocks, gender, binge drinking, and adolescent violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:105–120. doi: 10.1177/0886260505281662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Sabo D, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP, Barnes GM. Jocks and athletes: College students’ reflections on identity, gender, and high school sports.. Paper presented at the American Sociological Association annual meeting, Montreal, Quebec, Canada..Aug, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (NCICP). [March 21, 2007];Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS) 2007 ( http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars)

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Sex differences in depression. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oler MJ, Mainous AG, III, Martin CA, Richardson E, Haney A, Wilson D, et al. Depression, suicidal ideation, and substance use among adolescents: Are athletes at less risk? Archives of Family Medicine. 1994;3:781–785. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RM, Hammermeister J, Scanlan A, Gilbert L. Is school sports participation a protective factor against adolescent health risk behaviors? Journal of Health Education. 1998;29:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression: Critical review. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:486–492. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies depression scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabo D, Miller KE, Melnick MJ, Farrell MP, Barnes GM. High school athletic participation and adolescent suicide. International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 2005;40(1):5–23. doi: 10.1177/1012690205052160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders CE, Field TM, Diego M, Kaplan M. Moderate involvement in sports is related to lower depression levels among adolescents. Adolescence. 2000;35:793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, Meyer PM, Sloane F, Raffel M, Pratt D. The big ten student suicide study. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 1997;27:285–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TR, Powell KE, Swann AC. Involvement in physical activity and risk for nearly lethal suicide attempts. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center . Promoting mental health and preventing suicide in college and university settings. Education Development Center, Inc.; Newton, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tomori M, Zalar B. Sport and physical activity as possible protective factors in relation to adolescent suicide attempts. International Journal of Sport Psychology. 2000;31:405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB. Physical activity, participation in team sports, and risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1997;12:90–93. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein MD, Smith DS, Wiesenthal DL. Masculinity and hockey violence. Sex Roles. 1995;33:831–847. [Google Scholar]

- Westefeld JS, Button C, Haley JT, Jr., Kettman JJ, MacConnell J, Sandil R, et al. College student suicide: A call to action. Death Studies. 2006;30:931–956. doi: 10.1080/07481180600887130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]