Abstract

This is an historical essay about Nicolas Andry, a French medical doctor (Lyon 1658–Paris 1742) who wrote in 1741 the famous book called “L’orthopedie”, which was soon after translated into English (1742) “Orthopaedia or the art of correcting and preventing deformities in children”. His life and works are detailed as the containment of the book composed of two volumes and many engravings (the crooked tree has become the symbol of numerous orthopaedic societies around the world). A discussion of semantics (ORTHO-PEDIE) and evolution of the meaning of this word is also discussed.

Keywords: History of orthopaedics, The word “orthopaedics”, The crooked tree

Although all orthopaedic surgeons know of the name Nicolas Andry, at least because of the word “orthopaedics” that he forged, and also because of the famous engraving of the “crooked tree” which illustrates his work and which has become a symbol for our specialty, very few know about his life and his work. Therefore, we thought that it would be interesting to present this illustrious author.

Homage needs to be made to a Lyonnais surgeon named Lucien Michel, passionately interested in culture and history, who was, we believe, the first to carry out extensive research on Andry, published in 1941 in the Album du Crocodile (the magazine of the residents of the Lyon Hospitals) in the middle of the Second World War, a period hardly conducive to the memorial ceremonies suggested on that occasion [1].

His life

Nicolas Andry was born in Lyon, in 1658, in the Catholic parish of Saint Nizier, on the banks of the river Saône (see the baptism certificate of August 24) of a relatively poor merchant family (Fig. 1). He had two older brothers (Antoine and Claude), both of whom were priests. After studying theology for a time, he abandoned this ecclesiastical career in 1690, took on the surname of Bois-Regard and went to study medicine at the Faculty of Rheims (a faculty that vied in reputation with the Faculty of Paris). When it was dissolved in 1694 by King Louis XIV, he retook his exams in Paris. In 1697, he defended one of his theses with the funny title “The relationship in the management of diseases between the happiness of the doctor and the obedience of the patient”. Such a subject can make us smile now but was usual at that time. We will quote several titles of theses of that time which will give us an idea of how medicine was perceived:

Is music necessary for good health?

Is heroism passed down from father to son?

Is love beneficial?

Are women easier to cure than men?

Is it a good idea to eat walnuts after fish, cheese after meat, lettuce before apples?

He himself directed some more serious titles of obvious interest to present times:

Is moderate exercise the best way to remain in good health?

Does frequent use of tobacco shorten one’s life?

Fig. 1.

Parish of Saint Nizier and the bridge La Feuillée (on the bank of the river Saône). Historical engraving

There are few references to the town of Lyon in his writings, apart from this sentence: “drinking water may come from a river, as in Paris, but the water from the Rhône and Saône is unhealthy and children should be given water taken from wells”.

The second half of the 17th century (when he was studying) corresponds, from a surgical point of view, to the infancy of surgery with the so-called barber surgeons. Andry pursued his career in the 18th century, under the reign of Louis XIV and especially Louis XV, who was very interested in surgery [2]. Surgery will progress significantly with some great names and this explains why Nicolas Andry will soon be fighting a rearguard battle. The presence of great classical authors is important (La Fontaine, Voltaire, Diderot) and we will return to these.

Although he was ambitious and very energetic, Andry had a rather turbulent life, being constantly in conflict with his peers. As a substitute, then full-blown Professor at the College of France and then Dean of the Faculty (1724), a critic for the Journal des Savants, he never ceased to hound his peers, particularly the “barber surgeons” and reduced them to the level of “sous médecins”: he suppressed the five recently created posts in operative medicine, forbade them to operate other than in the presence of a doctor and prevented them from granting exemption from the restrictive customs of Lent which amounted to sheer harassment. This virulence, well illustrated in his pamphlet of 1738 “Cleon à Eudoxe touchant la prééminence de la médecine sur la chirurgie” (on the pre-eminence of medicine over surgery), which raises a smile when one realises that its author is the man that, two centuries later, orthopaedists will recognise as their “father”: “barbers are these people who shave their customers every day in their shops where one can read: In this house we shave you clean”. This pamphlet, Cléon à Eudoxe, earned him an equally spiteful reply from the surgeon Des Rosiers, in the form of a satirical engraving that we will come back to. He then turned his controversial talents to his faculty colleagues who described him as a “superb, scornful, confused, contemptuous, irascible and jealous doctor journalist!” Andry was eventually “beaten” after a merciless battle: he was dismissed from his job at the Journal des Savants and forced to resign as a Dean.

His private life saw him married three times with the arrival of a daughter from his third wife. He died in Paris on 13 March 1742, at the age of 84, a year after writing his famous book L’orthopédie. Such was the life of this man with his strong personality, who, even after two and a half centuries, appears to have been as much a persecutor as persecuted himself. In fact, we can read the following comments about him in the Dictionnaire des Sciences Médicales (quoted by Kirkup [3, 4]: “if he had spent as much time on useful work as he spent on base intrigues he could have had a place alongside the most famous doctors France has produced” and also “he mercilessly criticised the writings of his fellow doctors and showed himself to be an unfair detractor rather than an impartial critic. The famous Jean-Louis Petit, who has been avenged by posterity, was all too often exposed to his envious, ill humour” (in 1705, Jean-Louis Petit wrote Les maladies des os [bone diseases], which was a far more instructive book than the “superficial” book written by Andry. When the second edition of this work was published in 1723, Andry launched a virulent attack on its author).

His work

Among his many writings, there are several philosophical texts of little interest and others which are no more than lampoons, but some of his publications were original and constructive and bear witness to careful observation, making recommendations which, even today, continue to be of interest. We will focus on two books written, respectively, at the age of 40 and then 80 years old and which deal with very different subjects: parasitology and orthopaedics.

-

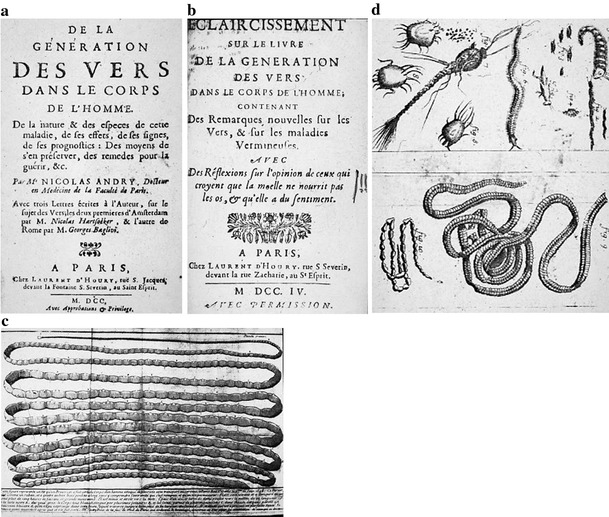

In 1700, he published his first book (Fig. 2): “De la géneration des vers dans le corps de l’homme. De la nature et des espèces de cette maladie, les moyens de s’en preserver et de la guérir”, translated as “The generation of worms in the human body. The different kinds and types of this disease and the ways of preventing and curing it”.

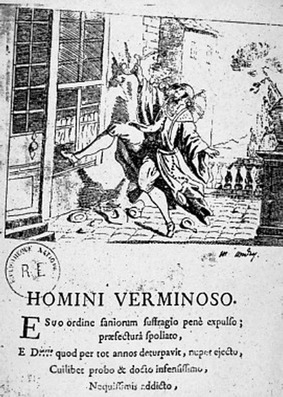

This work earned him the title of the “father of parasitology”, even if his explanation of the worm pathology was often fanciful. There are 12 chapters (the 11th of which is about “spermatic worms”: it compares spermatozoa with other worms and this desire to connect spermatozoa and parasites is somewhat curious!). However, the work contains beautiful engravings. In 1704, another book will supplement the former on “verminous diseases”. These two books gave rise to notoriety and mockery (not to mention contempt), but the controversial context that surrounded him can easily explain these reactions. Valisnieri baptised him “homo vermiculosus” and, later, he will be given the nickname of “homini verminoso” on the cover of “In answer to the lampoon Cléon to Eudoxe” (Fig. 3). In 1748, Julien Offray de la Metrie, a doctor and satirical writer, wrote the “Portrait of verminosus” in the following terms: “I have shown you this original engraving representing a doctor from the Faculty kicking down the door of a barber-surgeon, carrying on his back a pot of eau de fougère (a purgative) crying “Fresh water! Who wishes to drink?” (an allusion to worms, which, according to Andry, were the cause of all illness). He then adds: “this man is the dishonoured father of orthopaedics”. Even Voltaire mentions Andry in his novel L’homme aux quarante écus (1785) saying: “these little men who are such good swimmers” (spermatozoa). “Andry spends so much time looking at man under a microscope that he reduces him to a caterpillar”.

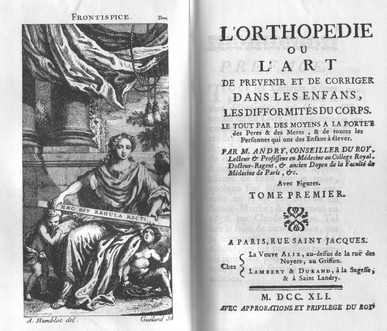

However, at the end of his life (when he was 82!), he wrote the work which would give him his present notoriety: “L’orthopédie ou l’art de prévenir et corriger dans les enfants les difformités du corps” (Fig. 4). This book was first published in Paris in 1741 in two volumes (in 12). It was an immediate success and was soon published abroad: in Brussels (1742), then London (1743) in English (“Orthopaedia or the art of correcting and preventing deformities in children”) (Fig. 5) and, finally, in Berlin (1744) in German (Orthopaedie).

Fig. 2.

a Treatise on the generation of worms, 1700. b Clarification of the treatise, 1704. c, dTwo plates illustrating worms

Fig. 3.

Satirical engraving of “Homini Verminoso” (French National Library)

Fig. 4.

The engraved frontispiece of the French edition of L’Orthopédie (1741)

Fig. 5.

The English edition “Orthopaedia” (1743)

It is pleasant to read, with simple suggestions full of practical, common sense in a similar style to the “Art d’être grand’père” (How to be a grandfather). This is underlined in the subtitle to his book in these words: “by such means as may easily be put into practice by PARENTS themselves, and all such as are employed in educating children”. It was illustrated with 12 superb engravings designed by Humblot and sculpted in wood by Guelard.

It is important to realise that this treatise is written neither for doctors nor for surgeons. It is a sort of homage to the grace and beauty of children; he wrote thus: “one must not neglect the body and let it become deformed, this would be against the intention of the Creator; this is the basic principle of orthopaedics” and then “this book is aimed exclusively at fathers and mothers and all people bringing up children who must try to prevent and correct any deformed part of the child’s body”. If one looks only at the principle of prevention, then these words have real meaning today.

The work is divided into four books, with the first three making up the first volume. A long “semantic” preface explains the origin of the word orthopaedia: “as to the title in question it is formed from two Greek words, “orthos” which means straight, devoid of deformity and “paidos” which means child. From these two words I formed that of Orthopaedics to express in one word what I have set out to do, namely to teach several ways of preventing and correcting deformities in children”.

This neologism, he explained, is similar to the method used previously by other authors like Scevolle de Sainte Marthe who, in 1584, wrote a work called “Pédo/trophie” (how to breastfeed infants) or Claude Quillet in 1656, who wrote “la Calli/pédie” (how to have beautiful children).

The first book reminds us of the surface “artistic” anatomy of the whole body, with a curious and interesting chapter on its external proportions. The style is pleasing and full of poetic, literary and historical quotations: the use of the word “gaster” refers to a fable by La Fontaine called Les membres révoltés contre l’estomac (the limbs that revolted against the stomach).

Books II and III deal with one of the most important parts of our specialty, more exactly that of “paediatric orthopaedics” in its modern meaning. Book II describes useful methods for preventing and correcting postural deformities of the trunk and the spine. Apart from a few comments which give rise to a smile, the therapeutic suggestions are correct and sensible: a healthy posture (a straw-seated chair, a writing table, the right position for sewing), the importance of active movement (as opposed to passive manipulations), using curiosity to help with a stiff neck, carrying a ladder or a weight on the side opposite the deformity (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

He recommends the carrying of a ladder to help correct scoliosis

And finally, to treat scoliosis, he suggests wearing a padded brace which should be changed every three months. Book III covers limb deformities: Andry distinguishes between inequalities that are congenital or acquired (by “emaciation”) and pseudo shortenings of the limbs due to dislocation (in this case, he recommends “a speedy intervention on the part of the surgeon”). We may notice that he also recommends loose swaddling in the fashion of the “negroes in Africa and the savages in Canada”, a principle still adhered to today. For curvature of the tibia, he suggests a “conservative” treatment: a gradual straightening of the limb “by bandaging the bent limb to an iron plate as if one wanted to straighten the crooked trunk of a young tree”. This is the famous engraving of the “crooked tree” often considered as representing a scoliosis correction, but this is wrong (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The famous engraving of the “crooked tree” (p. 282 of vol. 1)

Club foot, according to Andry, should be treated early and without operation (which corresponds to present day practice in the method described by Ponseti!). He also recommended bandaging and shoes.

Finally, certain chapters remain interesting, such as, for example, the treatment of extra fingers with no bone structure (dealt with by a strangulation thread), the one about left-handed children where one glimpses a modern day approach (namely, not to contrary the child in his everyday life except for gestures of “politeness”). Trauma are not dealt with in volume I.

And lastly in the fourth book (the whole of Volume II), he covers the deformities of the head and face in considerable detail. Orthopaedia today does not deal with these sorts of deformities. However, many other specialists will enjoy this section, namely, maxillofacial surgeons, dental orthopaedics and aesthetic surgeons. He covers the harelip, sticking out ears, the principle of using strips of flesh (to repair a broken nose, taken from the arm) and even certain principles of speech therapy. The work ends curiously enough with some moral advice which is actually rather aggressive towards nannies who were “badly trained in looking after the physical and moral development of children”. He made three recommendations: everything should be done to avoid the child experiencing revenge, lies and fear.

Throughout the book, Andry emphasises his love of the beauty of the human form and this gives him what is nowadays a very modern approach. In a chapter on surgery and orthopaedics, published in the Encyclopaedia by Diderot and D’Alembert, there is considerable mention made of Andry and this will help establish the term and concept of orthopaedics (illustrated by an amusing engraving of a child righting a tree) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Engraving illustrating the chapter “Orthopaedics” in the Encyclopaedia, Paris, 1763

Today, it is virtually impossible to find this book by Nicolas Andry, even amongst book lovers. It was re-published as a facsimile in 1996 at the request of the present author and with the backing of the SOFCOT.

On the good fortune of the word “orthopaedics”

This word alone triggered, as its author did in his time, a certain amount of controversy, even though one has to admit that this is the word used worldwide today to mean “surgical orthopaedics” (adults and children) in its two facets: “orthopaedic” (conservative) and “surgical” (operative). As Andry describes in his preface, this neologism was made up of two Greek roots. This invention followed other less successful ones (callipédie and pédotrophie). The term will be taken up by Diderot in his Encyclopaedia, which will help establish it. In his turn, Venel will use it when he decides to call his clinic in Switzerland an “orthopaedic Institute” and then many others will follow suit during the 19th century. These institutes specialised in “physiotherapy” for well off young girls. In 1805, this term appeared for the second time in a treatise “New orthopaedics” published by Desbordeaux before being in common use in the many orthopaedic treatises that were published around that time. Purists were alarmed by this term, which essentially meant the correction of children’s deformities, thus, turning the expression “paediatric orthopaedics” into a pleonasm and making nonsense of the term “orthopaedics in adults”. In 1820 in the Dictionary of Medical Science, Fournier-Bescay had already declared that the etymology of the word “orthopaedics” was incorrect, which no doubt explains the different terms being used: l’orthomorphie created by Delpech in 1828 in Montpellier, l’orthosomatique by Bricheteau and d’Invernois from Paris and l’orthopraxie suggested by Heather-Bigg in London in 1867. Nevertheless, it is the word ORTHOPAEDICS which has survived, no doubt because it is easy to pronounce! It has been adopted and translated all over the world: orthopédie, orthopaedica, orthopedic, orthopaedische, orthopedia, orthopedicka, orthopaedics.

The change in meaning of this word is interesting, as the sense has been narrowed and then enlarged. To begin with, we saw that this word concerned children, with the connotation of prevention and seeking a beautiful human form. The importance of “conservative treatment” rather than using “surgery” corresponds well to this first definition. Then, a century later, in the 1840s, there was a rapid increase in surgical procedures (tenotomies with Stromayer in Hanover, surgery with Little in London) and it was now accepted that it was bone and joint surgery that had come to the forefront. Professors of “orthopaedic and infantile surgery” in the 20th century illustrate this semantic confusion. Even if the term has been adopted today, one must, nevertheless, distinguish between surgical orthopaedics which concerns adults (and which includes both conservative and operative treatments) and “paediatric orthopaedic surgery” which is reserved for children and adolescents. Many logos have been derived from the crooked tree; we can mention those of two French Orthopaedic Societies that exist side by side in good harmony: the French Society of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology (SOFCOT) and the French Society of Paediatric Orthopaedics (SOFOP) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Two logos derived from the “crooked tree” (SOFCOT and SOFOP)

The portrait of Nicolas Andry (lost, found, lost again…)

In conclusion, it may be interesting to look at the portrait of this man who had so many ups and downs in his life [5]. Andry’s portrait is not to be found on the frontispiece of his works (which was the norm in the 13th century). An authentic canvas of Andry was part of the collection of the Paris Faculty of Medicine until the end of the 19th century: this “very good portrait” referred to by Chereau, mysteriously disappeared and was then found 50 years later in the office of the Dean. This supposed portrait, painted by De Troy in 1738, shows him wearing a wig, an ermine cape and a red coat (Fig. 10). In the opinion of Bonnola (a pupil of Putti’s), this canvas cannot represent Andry (who appeared much younger than his real age of 80). Doubt must remain though since this supposed portrait was no sooner found than it disappeared again! Our recent research, with the help of curators in Paris, has not turned up anything new.

Fig. 10.

The portrait of N. Andry by Chereau

The irony of fate (or the revenge of his contemporaries?) has left us with only one representation of Andry, which is the etching entitled “Homini verminoso” (Worm man) to be found in the French National Library.

Acknowledgment

Thanks go to Scott Mubarak (MD) for reviewing the English manuscript.

References

- 1.Michel L. A propos du prochain bicentenaire de “l’orthopédie”. Rev Chir Orthop. 1938;25:282–286. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sicard A. Les origines de l’Académie Nationale de Chirurgie. Ann Chir. 1998;52:338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dictionnaire des Sciences Médicales . Nicolas Andry in T1. Paris: Panckouke; 1820. pp. 252–254. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkup J. Nicolas Andry et l’orthopédie. Hist Sci Méd T. 1993;28(3):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michel L. Le portrait de N. Andry a-t-il été retrouvé? Rev Chir Orthop. 1939;26:382. [Google Scholar]