Abstract

The kinetics of the RAFT polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene using a trithiocarbonate chain transfer agent, S-1-dodecyl-S′-(α,α′-dimethyl-α″-acetic acid)trithiocarbonate, DDMAT, was investigated. Parameters including temperature, percentage initiator, concentration, monomer-to-chain transfer agent ratio and solvent were varied and their impact on the rate of polymerization and quality of the final polymer examined. Linear kinetic plots, linear increase of Mn with monomer conversion and low final molecular weight dispersities were used as criteria for the selection of optimized polymerization conditions, which included a temperature of 70 or 80 °C with 10 mol% AIBN initiator in bulk for low conversions or in 1,4-dioxane at a monomer-to-solvent volume ratio of 1:1 for higher conversions This study opens the way for the use of DDMAT as a chain transfer agent for RAFT polymerization to incorporate p-acetoxystyrene together with other functional monomers into well-defined copolymers, block copolymers and nanostructures.

Keywords: Reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization, trithiocarbonate, 4-acetoxystyrene, p-acetoxystyrene, poly(4-acetoxystyrene), poly(p-acetoxystyrene)

Introduction

Phenolic functional polymers such as poly(p-hydroxystyrene) and its derivatives have attracted much attention due to their potential applications as polar, functional, stimuli-responsive and reactive materials in research and industry. For instance, they have performed as components of high resolution imaging materials, light-emitting materials, photoresists, adhesives, supports for solid-phase and combinatorial synthesis, stabilizers, polymeric antioxidants, polymer blends and metal treatment materials.1–8 Poly(p-hydroxystyrene) has also been incorporated into block copolymers as sites for further functionalization or to incur pH-responsive properties to the block copolymers and their subsequent nanoscopic assemblies.9–12 For each of these utilizations of the phenolic functionalities, it is important to control their locations within the overall macro-, micro- or nanoscopic materials, which are determined by the sequence with which p-hydroxystyrene is placed topologically along the polymer frameworks.

The synthesis of well-defined polymers of p-hydroxystyrene requires protection/deprotection strategies, in most cases, because the reactivity of the phenolic unit presents difficulties of handling and polymerization control. Although, standard free radical polymerization allows for the synthesis of low molecular weight poly(p-hydroxystyrene), ~104 Da, it offers little control over the molecular weight of the polymers obtained due to the phenolic OH group acting as a transfer agent. In addition, synthesis of polymers with higher molecular weights via this technique is limited due to aromatic hydroxy compounds being inhibitors or retarders for radical chain reactions.13–14 p-Hydroxystyrene is not compatible with anionic polymerization as the acidic phenolic proton undergoes reaction with both anionic initiators and active propagating chain ends. Although well defined polymers of p-hydroxystyrene have been obtained using cationic polymerization,15 early reports of the cationic polymerization of p-hydroxystyrene stated that the strong phenolic activation of the ring could result in some degree of alkylation of the aromatic ring yielding a polymer with a structure which is not completely polyvinylic.16 Examples of protecting groups include tert-butyl, tert-butoxycarbonyl, trimethylsilyl, tert-butyldimethylsilyl and acetyl. The acetyl protecting group is attractive because it is more atom economical than is the tert-butoxycarbonyl unit, is more easily removed than is the tert-butyl and is more stable than is the trimethylsilyl group. Polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via anionic13 and cationic17 polymerizations has not been largely successful in part due to the electronic nature of the pendant group. However, with the development of controlled radical polymerization methods, such as nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP),18 atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP),19–20 and reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization,21–22 tools have been made available to access well-defined poly(p-hydroxystyrene) by the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene, followed by deprotection.

The controlled radical polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene was first reported by Leduc et al. in 1996 as “living” free radical polymerization.23–24 The NMP of p-acetoxystyrene was then further evaluated through a full kinetic study,25 which allowed for investigation of the influences of chain length and molecular weight dispersity on polymer solubility in relation to the use of poly(p-hydroxystyrene) in photoresists. The effects of different initiating systems26 was shown to allow for control over the chain end compositions, which was followed by homolysis of the alkoxyamino chain terminus and radical addition onto C60 to produce photoreactive polymer-bound C60 composite materials. The preparation of random, gradient and block copolymers of p-hydroxystyrene via NMP has also been reported, as interesting multi-functional materials, with applications ranging from polymer blends to reconstructed surfaces to high functionality and pH-responsive nanoassemblies.10,27–31

ATRP of p-acetoxystyrene was first reported in 1997 by Gao et al.,32 and its homo- and co-polymerizations were then studied.5,33–35 The preparation of block copolymers with poly(p-acetoxystyrene) either as the first or second block was demonstrated, confirming the living nature of the polymerization.34,36–37 More recently, Luo et al. reported the use of iron-based activator generated by electron transfer (AGET) ATRP38 for the preparation of well-defined poly(p-acetoxystyrene).

In recent years, the RAFT polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene was developed, and it has seen significant advancement as a controlled radical polymerization technique for a broad variety of functional monomers.39–44 Benicewicz reported the use of several dithioester chain transfer agents for the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene,45 and then extended to a new cyanobenzyl-dithioester.46 This ability to modify the chain end functionality by the nature of the chain transfer agent employed is of great importance to the preparation of functional materials.47 Moreover, control over the macromolecular topology has been demonstrated with the synthesis of linear and star polymers48 as well as the preparation of block copolymers.40

With our interest in the preparation of multi-functional block and graft copolymers having a high degree of control over every aspect of their composition and structure, while also doing so via atom economical synthetic methodologies, we investigated the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene using a trithiocarbonate chain transfer agent. S-1-dodecyl-S′-(α,α′-dimethyl-α″-acetic acid)trithiocarbonate, DDMAT, is a versatile chain transfer agent, which incorporates chain end functionality and allows for (block) copolymerization of a wide variety of functional comonomers, including styrenics, methacrylates, acrylates, acrylamides, N-vinylpyrrolidinone, isoprene and acrylic acid.49–56 Herein, is reported a kinetic investigation of the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene using DDMAT as the chain transfer agent, examining the influence of several experimental parameters on the rate of polymerization and the quality of the final polymers.

Results and Discussion

In order to identify optimized conditions for the preparation of well-defined polymers containing p-acetoxystyrene using RAFT polymerization, several parameters were evaluated (Table 1). The impact of variation of temperature, percentage initiator, concentration, targeted degree of polymerization and solvent on the rate of the polymerization, the control of the polymerization, and the quality of the final polymer obtained were assessed. Standard polymerization conditions are shown in Scheme 1.

Table 1.

Conditions for the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT polymerization with DDMAT as RAFT agent and AIBN as initiator and the resulting monomer conversion data.

| Exp. | Temp. (°C) | Initiator (mol%)c | Monomer: Solvent (v/v ratio) | [Monomer]/[DDMAT] | Solvent | Monomer conv. after 3 h (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 10 | n/a | 100 | bulk | 6 ± 4a |

| 2 | 70 | 10 | n/a | 100 | bulk | 28 ± 9a |

| 3 | 80 | 10 | n/a | 100 | bulk | 65 ± 10a |

| 4 | 70 | 5 | n/a | 100 | bulk | 15 ± 1b |

| 5 | 70 | 20 | n/a | 100 | bulk | 40 ± 5a |

| 6 | 70 | 10 | 1:1 | 100 | 1,4-dioxane | 10 ± 1a |

| 7 | 80 | 10 | 1:1 | 100 | 1,4-dioxane | 22 ± 4a |

| 8 | 70 | 10 | 2:1 | 100 | 1,4-dioxane | 32 ± 2a |

| 9 | 70 | 10 | 1:2 | 100 | 1,4-dioxane | 9 ± 3a |

| 10 | 70 | 10 | n/a | 50 | bulk | 46 ± 4b |

| 11 | 70 | 10 | n/a | 200 | bulk | 25 ± 3b |

| 12 | 80 | 10 | 1:1 | 50 | 1,4-dioxane | 31 |

| 13 | 80 | 10 | 1:1 | 120 | 1,4-dioxane | 22 |

| 14 | 80 | 10 | 1:1 | 200 | 1,4-dioxane | 15 |

| 15 | 80 | 10 | 1:1 | 416 | 1,4-dioxane | 10 |

| 16 | 70 | 10 | 1:1 | 100 | DMF | 15 ± 3b |

| 17 | 70 | 10 | 1:1 | 100 | 2-butanone | 18 ± 1b |

Calculated from experiments performed in triplicate.

Calculated from experiments performed in duplicate.

The mol% initiator is relative to chain transfer agent, DDMAT.

Scheme 1.

General conditions for the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT polymerization with DDMAT as RAFT agent.

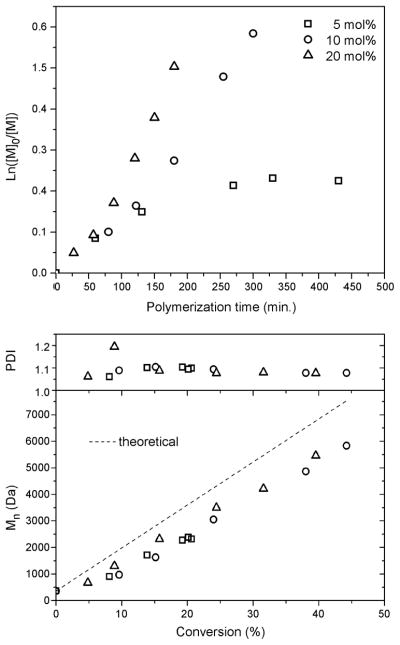

The temperature was varied in bulk (experiments 1–3, Table 1) and in the presence of 1,4-dioxane as solvent (experiments 6 and 7, Table 1). The polymerization in bulk at 60 °C gave varying results and generally was very slow, leading to only 10% conversion after 4 h. An increase of temperature from 70 to 80 °C, for the bulk- or solution-state polymerizations, resulted in an increase of the polymerization rate by three-fold (Fig. 1). The addition of 1,4-dioxane as a solvent, in a 1:1 volume ratio with respect to monomer, resulted in an expected decrease in the rate of polymerization, compared to the polymerization in bulk; the polymerization at 70 °C in bulk showed a similar rate to that at 80 °C in 1,4-dioxane. Kinetic plots for all polymerizations were linear, molecular weight increased linearly with conversion and PDI decreased (Fig. 1). All polymers exhibited final polydispersity indices around 1.1. Variation in the polymerization temperature did not influence the living/controlled character of the polymerization and well-defined polymers could be obtained both at 70 and 80 °C in bulk and in the presence of 1,4-dioxane. Polymerizations were repeated several times to assess the reproducibility of the results (Fig. 1). Deviation between the kinetic plots of the different runs was low. The results obtained were, therefore, considered reproducible.

Figure 1.

Influence of temperature and solvent on the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT with DDMAT as RAFT agent: kinetic plots and plots of Mn and PDI vs. conversion.

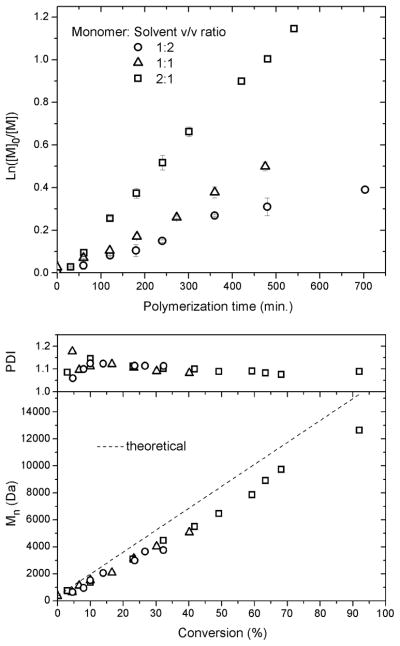

The amount of AIBN with respect to chain transfer agent, DDMAT, was varied from 5 to 10 and 20 molar percent (experiments 2, 4 and 5, Table 1), with all other parameters held constant. The polymerizations were carried out in bulk at 70 °C with [Monomer]/[DDMAT] = 100. An increase in the amount of AIBN resulted in an increase in the rate of polymerization (Fig. 2). Both polymerizations with 10 and 20 mol% AIBN resulted in linear kinetics (Fig. 2), and gave Mn vs. conversion plots that were linear and decreasing PDI values with monomer conversion (Fig. 2) to 1.07. Polymerizations conducted with 5 mol% AIBN to DDMAT showed some decrease in the rate of polymerization with time and monomer conversion halted at ca. 20%. Although the final PDIs were similar to those obtained with 10 and 20 mol% AIBN, this amount of initiator did not allow for a living/controlled system as the polymerizations ceased.

Figure 2.

Influence of the percentage of AIBN initiator on the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT with DDMAT as RAFT agent: kinetic plots and plots of Mn and PDI vs. monomer conversion.

Study of the bulk polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene was limited due to the high viscosity of the polymerization mixture past 30% conversion, therefore, 1,4-dioxane was employed as a solvent to reach higher conversions. In order to assess the amount of solvent necessary to decrease the viscosity of the polymerization mixture at high conversion, while still providing high polymerization rates and well-defined final polymers, polymerizations were carried out with varying ratios of monomer to 1,4-dioxane, from 2:1 to 1:1 and 1:2 (experiments 8, 6 and 9, respectively, Table 1). The polymerizations were performed at 70 °C with [Monomer]/[DDMAT] = 100 and 10 mol% AIBN initiator. It was found that, as can be expected, diluting the polymerization mixture resulted in a decrease in the polymerization rate. Monomer to solvent ratios of 2:1 and 1:1 gave linear kinetic plots, whereas a 1:2 ratio showed a slight decrease in the rate of polymerization with time (Fig. 3). Although, Mn vs. conversion was linear for all polymerizations, a higher final PDI was observed with the 1:2, monomer:solvent ratio. With a ratio of 2:1, it was possible to reach 90% conversion and maintain the PDI below 1.1, and at a ratio of 1:1, well controlled polymerization occurred also, while maintaining a lower viscosity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Influence of 1,4-dioxane dilution on the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT with DDMAT as RAFT agent: kinetic plots and plots of Mn and PDI vs. monomer conversion.

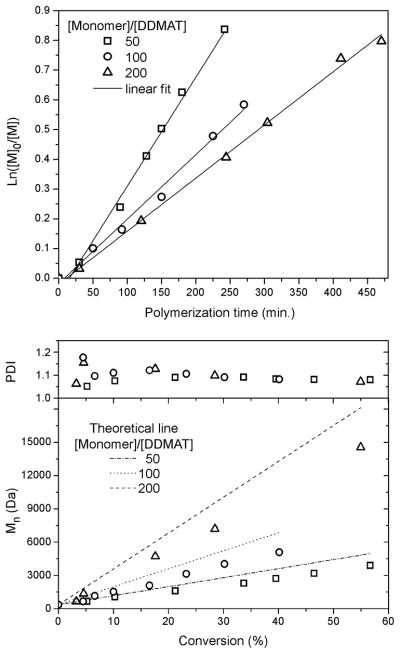

The influence of the relative concentrations of monomer to chain transfer agent was evaluated by a series of experiments that involved variation of the [monomer]/[DDMAT] values from 50, 100 and 200 in bulk (experiments 2, 10–11, Table 1), and up to 400 in 1,4-dioxane (experiments 12–15, Table 1). In each case, the monomer conversion was allowed to proceed to ca. 50%, giving polymers having degrees of polymerization of ca. 25, 50, 100 and 200, respectively (Table 2). The ratio of AIBN initiator to DDMAT chain transfer agent and the temperature were held constant at 10 mol% and 70 °C, with the absolute amounts of AIBN and DDMAT being held constant, while the amounts of monomer (and solvent, for those polymerizations that were performed with 1,4-dioxane) were increased. In the polymerizations performed in 1,4-dioxane, the volume ratio of monomer to solvent was maintained at 1:1. Increase of the targeted degree of polymerization corresponded to a dilution of the radicals and, thereby, resulted in a decrease in the rate of polymerization (Fig. 4). Mn vs. conversion plots were linear for all polymerizations. In general, although conversion was lower for higher targeted DPs, more units were added per growing chain with monomer conversion, giving higher Mn with conversion. They also all showed PDIs decreasing with conversion and low final PDIs (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained in 1,4-dioxane with the exception that when a degree of polymerization of ca. 200 was targeted, the final polymer exhibited an increased PDI, Table 2. Increase in [monomer]/[DDMAT] from 50 to 200 did not result in significantly broader molecular weight distributions (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene in 1,4-dioxane (1:1 monomer/solvent volume ratio) with 10 mol% AIBN at 80 °C with varying [monomer]/[DDMAT], allowed to proceed to similar extents of monomer conversion, and therefore, giving different targeted DP values.

| Exp. | [monomer]/[DDMAT] | Final monomer conversion (%) | Final DP (NMR) | PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 50 | 42 | 23 | 1.07 |

| 13 | 121 | 50 | 61 | 1.08 |

| 14 | 200 | 64 | 128 | 1.10 |

| 15 | 416 | 56 | 235 | 1.28 |

Figure 4.

Influence of [monomer]/[DDMAT] on the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT: kinetic plots and plots of Mn and PDI vs. monomer conversion.

Figure 5.

GPC chromatograms of final polymers obtained with different targeted DP values for polymerizations of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT with DDMAT as RAFT agent in 1,4-dioxane.

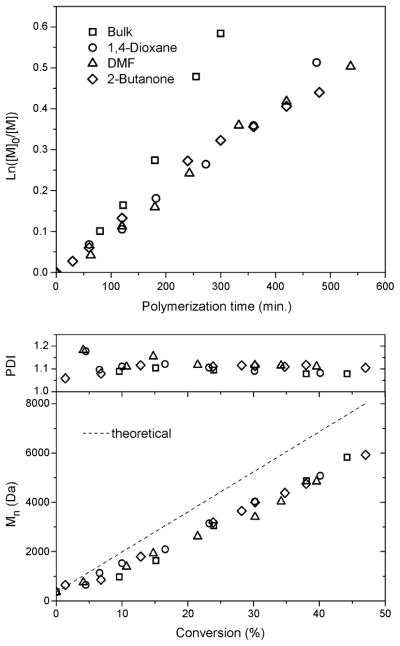

Study of the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene was extended to other solvents; N,N-dimethylformamide and 2-butanone were used in addition to 1,4-dioxane (experiments 16, 17 and 7, Table 1). All other parameters were kept constant. Polymerizations were carried out at 70 °C with 10 mol% AIBN initiator, [Monomer]/[DDMAT] = 100 and a volume ratio of monomer to solvent of 1:1. The kinetic and molecular weight versus conversion plots were compared to that of a polymerization conducted in bulk. As reported earlier, addition of solvent to the polymerization resulted in a decrease in the polymerization rate. All polymerizations with solvent proceeded at similar rates (Fig. 6). The kinetic plots were generally linear, although the polymerizations in bulk and in 1,4-dioxane provided the best linear fits. Mn vs. conversion plots for all polymerizations were linear and followed the same trend (Figure 6, right panel). PDIs for the polymerizations in 2-butanone and DMF did not decrease with conversion and stayed relatively constant, above 1.1. Both polymerizations in bulk and with 1,4-dioxane showed a decrease of PDI with conversion, with a final PDI around 1.08 (Fig. 6). Although, from this study, it may be considered that 1,4-dioxane is an optimal solvent, the performance of the polymerization in each of the three solvents is suitable for the preparation of well-defined poly(p-acetoxystyrene). Having an ability to perform the polymerization in a number of different solvents will be beneficial as this RAFT polymerization is extended to copolymerizations that include p-acetoxystyrene.

Figure 6.

Influence of different solvents on the polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene via RAFT with DDMAT as RAFT agent: kinetic plots and plots of Mn and PDI vs. monomer conversion.

Experimental

Instrumentation

Infrared spectra were obtained on a Perkin–Elmer Spectrum BX FTIR system as neat films on NaCl plates. 1H NMR (300 and 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (75 and 125 MHz) spectra were recorded on either a Varian Mercury 300 MHz or Inova 500 MHz spectrometer using the solvent as internal reference. Tetrahydrofuran-based gel permeation chromatography (THF GPC) was conducted on a system equipped with a Waters Chromatography, Inc. (Milford, MA) model 1515 isocratic pump, a model 2414 differential refractometer, and a Precision Detectors, Inc. (Bellingham, MA) model PD-2026 dual-angle (15° and 90°) light scattering detector and a three-column set of Polymer Laboratories, Inc. (Amherst, MA) Styragel columns (PLgel 5μm Mixed C, 500 Å, and 104 Å, 300 × 7.5 mm columns). The system was equilibrated at 35 °C in THF, which served as the polymer solvent and eluent (flow rate set to 1.00 mL/min). Polymer solutions were prepared at a known concentration (ca. 3 mg/mL) and an injection volume of 200 μL was used. Data collection was performed with Precision Detectors, Inc. Precision Acquire software. Data analysis was performed with Precision Detectors, Inc. Discovery 32 software. The differential refractometer was calibrated with standard polystyrene material (SRM 706 NIST), of known refractive index increment dn/dc (0.184 mL/g).

Materials

p-Acetoxystyrene (AcS) (99 %) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO) and was purified by passage over a column of neutral alumina prior to use. AIBN (98%, Aldrich) was recrystallized from methanol. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), 1,4-dioxane (99%), tetrahydrofuran (THF, ≥99.0%, with 250 ppm BHT as inhibitor), diethyl ether (≥99 %, anhydrous), methanol (≥99.9%), hexanes (ACS reagent, ≥98.5%) and 2-butanone (ACS reagent, ≥99.0%) were used as received from Sigma Aldrich. Chloroform-d, 1,4-dioxane-d8 (Cambridge Isotope Labs) were used as received. Nitrogen ultra-high purity grade gas (99.999%) was used as received from Praxair (St. Louis, MO). The RAFT agent, S-1-dodecyl-S′-(α,α′-dimethyl-α″-acetic acid)trithiocarbonate, DDMAT, was prepared as previously reported.49,57

General procedure for RAFT polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene in bulk

In a dry Schlenk tube were added S-1-dodecyl-S′-(α,α′-dimethyl-α″-acetic acid)trithiocarbonate, DDMAT (0.0902 g, 0.247 mmol), p-acetoxystyrene (4.0035 g, 24.7 mmol), AIBN (4.2 mg, 0.025 mmol). The tube was sealed with a rubber septum, the solution degassed via three freeze-pump-thaw cycles and then placed under nitrogen atmosphere. The polymerization was started by placing the tube in an oil bath at 70 °C. The polymerization was sampled regularly for 1H NMR and GPC analyses. The polymerization was stopped after 300 minutes by allowing it to cool, venting the tube, and adding tetrahydrofuran. The polymer was isolated by three consecutive precipitations from THF into methanol/water (9/1 v/v). Final conversion 56%, expected yield 2.36 g, recovered 1.61 g (68%). Mnconversion = 9,500 Da, MnGPC = 8,400 Da, Mw/Mn = 1.07. (Tg) = 93 °C. Tdecomp = 200–325 °C (10% mass), 325–450 °C (complete). IR (cm−1): 3033, 2924, 2853, 1762, 1604, 1504, 1422, 1368, 1213, 1195, 1166, 1015, 911, 847, 558. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, ppm): δ 7.1-6.2 (broad, ArH), 3.25-3.19 (broad, S-CS-S-CH2-), 2.3-2.2 (broad, -COO-CH3), 2.2-1.2 (broad, -CH2-CH(Ar)-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, ppm): δ 169.1, 148.5, 142.1, 128.2, 121.3, 44-38, 20.9.

General procedure for RAFT polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene in 1,4-dioxane

In a dry Schlenk tube were added DDMAT (0.0899 g, 0.246 mmol), p-acetoxystyrene (8.0139 g, 49.4 mmol), AIBN (4.0 mg, 0.024 mmol) and 1,4-dioxane (8 mL). The tube was sealed with a rubber septum, the solution degassed via three freeze-pump-thaw cycles and then placed under nitrogen atmosphere. The polymerization was started by placing the tube in an oil bath at 70 °C. The polymerization was sampled regularly for 1H NMR analysis. The polymerization was stopped after 600 minutes by venting the tube and cooling down. The polymer was isolated by three subsequent precipitations from THF into methanol/water (8/2 v/v). Final conversion 64%, expected yield 5.12 g, recovered 3.96 g (77%). Mnconversion = 21,100 Da, MnGPC = 17,200 Da, Mw/Mn = 1.07. (Tg) = 95 °C. Tdecomp = 200–325 °C (10% mass), 325–450 °C (complete). IR (cm−1): 3034, 2925, 2854, 1763, 1604, 1505, 1432, 1369, 1216, 1199, 1166, 1016, 911, 847, 559. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, ppm): δ 7.1-6.2 (broad, ArH), 3.25-3.19 (broad, S-CS-S-CH2), 2.3-2.2 (broad, -COO-CH3), 2.2-1.2 (broad, -CH2-CH(Ar)-). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3, ppm): δ 169.3, 148.8, 142.4, 128.5, 121.2, 47-39.5, 21.3.

Conclusions

In this investigation into the kinetics of the RAFT polymerization of p-acetoxystyrene with DDMAT as a RAFT agent, parameters including temperature, percentage initiator, concentration, targeted degree of polymerization and solvent were varied and their impact on the rate of polymerization assessed. Optimized polymerization conditions were defined as a temperature of 70 or 80 °C with 10 mol% AIBN initiator in bulk for low conversions or in 1,4-dioxane for higher conversions, and at a monomer to solvent volume ratio of 1:1. Linear kinetic plots, linear increase of Mn with monomer conversion and low molecular weight dispersities were obtained under these conditions. Targeting high degrees of polymerization (>400) was shown to result in broadened molecular weight distributions. Future work will include the use of DDMAT as chain transfer agent for RAFT polymerization to incorporate p-acetoxystyrene together with other functional monomers into well-defined copolymers, block copolymers and nanostructures.58–59

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health as a Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology (HL080729) and the National Science Foundation under grant numbers DMR-0451490 and DMR-0906815.

References

- 1.Macdonald SA, Willson CG, Frechet JMJ. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1994;27:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang CB, Lennon EM, Fredrickson GH, Kramer EJ, Hawker CJ. Science. 2008;322:429–432. doi: 10.1126/science.1162950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguiar M, Karasz FE, Akcelrud L. Macromolecules. 1995;28:4598–4602. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasrullah JM, Raja S, Vijayakumaran K, Dhamodharan R. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2000;38:453–461. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho H, Kim J, Patil P, Kim JY, Kim TH. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2007;103:3560–3566. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams RE. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 1972;10:2123–2127. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deleuze H, Sherrington DC. Journal of the Chemical Society-Perkin Transactions 2. 1995:2217–2221. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang ML, Jiang M, Zhang YB, Wu C, Feng LX. Macromolecules. 1997;30:2313–2319. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mountrichas G, Pispas S. Macromolecules. 2006;39:4767–4774. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee NS, Li YL, Ruda CM, Wooley KL. Chemical Communications. 2008:5339–5341. doi: 10.1039/b000000x/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menichetti S, Viglianisi C, Liguori F, Cogliati C, Boragno L, Stagnaro P, Losio S, Sacchi MC. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2008;46:6393–6406. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vestberg R, Piekarski AM, Pressly ED, Van Berkel KY, Malkoch M, Gerbac J, Ueno N, Hawker CJ. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:1237–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakahama S, Hirao A. Progress in Polymer Science. 1990;15:299–335. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato M. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 1969;7:2175–2184. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satoh K, Kamigaito M, Sawamoto M. Macromolecules. 2000;33:5405–5410. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato M. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 1969;7:2405–2410. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanaoka S, Eika Y, Sawamoto M, Higashimura T. Macromolecules. 1996;29:1778–1783. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawker CJ, Bosman AW, Harth E. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:3661–3688. doi: 10.1021/cr990119u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamigaito M, Ando T, Sawamoto M. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:3689–3745. doi: 10.1021/cr9901182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matyjaszewski K, Xia JH. Chemical Reviews. 2001;101:2921–2990. doi: 10.1021/cr940534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Australian Journal of Chemistry. 2005;58:379–410. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barner-Kowollik C, Perrier S. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2008;46:5715–5723. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leduc MR, Hawker CJ, Dao J, Frechet JMJ. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118:11111–11118. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawker CJ, Barclay GG, Dao JL. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1996;118:11467–11471. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barclay GG, Hawker CJ, Ito H, Orellana A, Malenfant PRL, Sinta RF. Macromolecules. 1998;31:1024–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamura H, Takemura T, Tsunooka M, Shirai M. Polymer Bulletin. 2004;52:381–391. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stehling UM, Malmstrom EE, Waymouth RM, Hawker CJ. Macromolecules. 1998;31:4396–4398. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray MK, Zhou HY, Nguyen ST, Torkelson JM. Macromolecules. 2004;37:5586–5595. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benoit D, Harth E, Fox P, Waymouth RM, Hawker CJ. Macromolecules. 2000;33:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodlert M, Harth E, Rees I, Hawker CJ. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2000;38:4749–4763. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Funk L, Brehmer M, Zentel R, Kang H, Char K. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2008;209:52–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gao B, Chen XY, Ivan B, Kops J, Batsberg W. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 1997;18:1095–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kotani Y, Kamigaito M, Sawamoto M. Macromolecules. 2000;33:6746–6751. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao B, Chen XY, Ivan B, Kops J, Batsberg W. Polymer Bulletin. 1997;39:559–565. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thibaud S, Moine L, Degueil M, Maillard B. European Polymer Journal. 2006;42:1273–1283. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Truelsen JH, Kops J, Batsberg W. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2000;21:98–102. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo SW, Huang CF, Lu CH, Lin HM, Jeong KU, Chang FC. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2006;207:2006–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo R, Sen A. Macromolecules. 2008;41:4514–4518. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evans AC, Skey J, Wright M, Qu WJ, Ondeck C, Longbottom DA, O’Reilly RK. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:6814–6826. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilles K, Theato P. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:1696–1705. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu B, Lowe AB. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:1877–1890. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li G, Wang H, Zheng H, Bai R. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2010;48:1348–1356. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen M, Moad G, Rizzardo E. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:6704–6714. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakwere H, Perrier S. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:6396–6408. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanagasabapathy S, Sudalai A, Benicewicz BC. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2001;22:1076–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li CZ, Benicewicz BC. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2005;43:1535–1543. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aoyagi N, Endo T. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:3702–3709. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaffey-Millar H, Hart-Smith G, Barner-Kowollik C. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2008;46:1873–1892. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai JT, Filla D, Shea R. Macromolecules. 2002;35:6754–6756. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang HJ, Deng JJ, Lu LC, Cai YL. Macromolecules. 2007;40:9252–9261. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noro A, Yamagishi H, Matsushita Y. Macromolecules. 2009;42:6335–6338. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang XL, Chen Z, Ran R. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2009;112:2486–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 53.He SJ, Zhang Y, Cui ZH, Tao YZ, Zhang BL. European Polymer Journal. 2009;45:2395–2401. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roy D, Cambre JN, Sumerlin BS. Chemical Communications. 2009:2106–2108. doi: 10.1039/b900374f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowe MD, Chang CC, Thamm DH, Kraft SL, Harmon JF, Vogt AP, Sumerlin BS, Boyes SG. Langmuir. 2009;25:9487–9499. doi: 10.1021/la900730b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bartels JW, Billings PL, Ghosh B, Urban MW, Greenlief CM, Wooley KL. Langmuir. 2009;25:9535–9544. doi: 10.1021/la900753r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lai JT. WO. The B.F.Goodrich Company; USA: 2001. p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J, Liu H, Boyer C, Bulmus V, Davis TP. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:899–912. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pietsch C, Fijten MWM, Lambermont-Thijs HML, Hoogenboom R, Schubert US. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2009;47:2811–2820. [Google Scholar]