Abstract

Background

Comparative effectiveness of interventional treatment strategies for the very elderly with acute coronary syndrome remains poorly defined due to study exclusions. Interventions include percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), usually with stents, or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). The elderly are frequently directed to PCI because of provider perceptions that PCI is at therapeutic equipoise with CABG and that CABG incurs increased risk. We evaluated long-term outcomes of CABG versus PCI in a cohort of very elderly Medicare beneficiaries presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Methods

Using Medicare claims data, we analyzed outcomes of multivessel PCI or CABG treatment for a cohort of 10,141 beneficiaries age 85 and older diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome in 2003 and 2004. The cohort was followed for survival and composite outcomes (death, repeat revascularization, stroke, acute myocardial infarction) for three years. Logistic regressions controlled for patient demographics and comorbidities with propensity score adjustment for procedure selection.

Results

Percutaneous coronary intervention showed early benefits of lesser morbidity and mortality, but CABG outcomes improved relative to PCI outcomes by three years (p < 0.01). At 36 months post-initial revascularization, 66.0% of CABG recipients survived (versus 62.7% of PCI recipients, p < 0.05) and 46.1% of CABG recipients were free from composite outcome (versus 38.7% of PCI recipients, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

In very elderly patients with ACS and multivessel CAD, CABG appears to offer an advantage over PCI of survival and freedom from composite endpoint at three years. Optimizing the benefit of CABG in very elderly patients requires absence of significant congestive heart failure, lung disease, and peripheral vascular disease.

Elderly individuals are the fastest growing segment of the US population. Projections show that those age 75 and older, currently 5% of the population, will triple in number by the middle of this century, and those age 85 and older, currently 4.7 million, will double in number to 9.6 million by 2030 [1, 2]. With age comes an increasing incidence of symptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD) requiring revascularization. Physicians will be challenged to advise elderly patients to choose among medical management, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). Published randomized trials comparing PCI with CABG demonstrate superior results for CABG in terms of long-term (5 to 6 years) composite outcome of death, repeat revascularization, repeat acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and stroke. Survival analysis from these same trials have generally favored CABG, but these study populations excluded the very elderly (age 85 and older) [3, 4].

Outcomes among the very elderly in cardiac surgery are associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared with outcomes for persons younger than 65 years [5]. A recent systematic review with meta-analysis from investigators concluded that coronary revascularization in octogenarians is reasonably tolerated but the preferred mechanism of revascularization remains unresolved [6]. The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group evaluated their own experience in octogenarians with multivessel disease undergoing PCI or CABG, concluding that CABG provided increased risk in the short term but enhanced long-term survival (up to eight years) [7].

To compensate for low representation and to include current drug-eluting stent (DES) therapy, we evaluated the comparative effectiveness of CABG versus PCI for very elderly Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and multivessel disease using a retrospective administrative database with a three-year follow-up period. The study analyzes two outcomes over time: survival and freedom from composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and revascularization.

Material and Methods

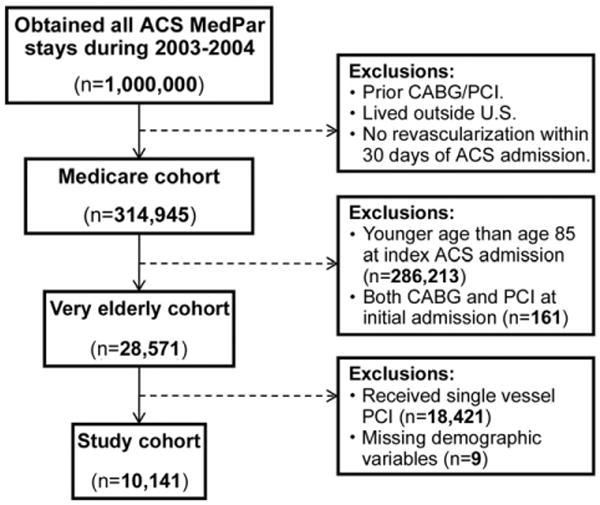

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina Biomedical Institutional Review Board. To identify our sample (Fig 1), we selected data for Medicare beneficiaries age 85 and older with an acute-care hospital Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) discharge record from January 2003 through mid-October 2004 with an ACS diagnosis and no diagnosis indicating prior (1 year) revascularization or valve disease.

Fig 1.

Diagram of cohort identification and exclusions. (ACS = acute coronary syndrome; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; MedPAR = Medicare Provider Analysis and Review; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.)

The October 2004 requirement was necessary to comply with a CMS (Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services) data request requirement of limiting our full sample to less than 1 million beneficiaries. Our sample therefore represents the full population of Medicare beneficiaries meeting our sample inclusion and exclusion criteria from January 2003 through mid-October 2004. This time period enabled our sample to include beneficiaries both before and after the initiation of Medicare reimbursement for drug-eluting stents in April 2004.

This process identified the “index admission” and the MedPAR records prior to the index admission were utilized to exclude patients with hospital stays identifying diagnoses or procedures indicating revascularizations or other exclusion conditions (eg, valve disease, heart transplant) prior to the index admission. The index admission record and subsequent MedPAR records identified patients with PCI (diagnosis-related group [DRG] codes 516, 517, 555, 556 for bare-metal stents or codes 526, 527, 557, 558 for drug-eluting stents) or CABG (DRG codes 106, 107, 109, 547, 548, 549, or 550) within 30 days at any hospital. This iterative methodology created a data file with 28,571 patients; of those, 22,768 were PCI patients with bare metal stents or DES (reimbursed by Medicare starting in April 2004) and 5,803 underwent CABG. The PCI sample was limited to 4,338 patients with intervention on more than one vessel (multivessel disease), resulting in a final analysis file of 10,141 Medicare beneficiaries. Among the patients with PCI, 47.7% received bare metal stents, 39.8% received DES, 8.3% received both types of stents, and 4.2% had PCI without a stent.

Outcomes were identified through December 2007 by the following: (1) the Medicare denominator file to observe date of death and (2) MedPAR hospital records to determine events of repeat hospitalization for revascularization, stroke, or subsequent AMI. Beneficiary characteristics (age, gender, race, and state (Medicaid) Part B buy-in status) came from the denominator file. Coding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality permitted construction of an Elixhauser comorbidity adjustment from diagnoses during the index and revascularization admission as well as admissions for one year prior to the index admission (see www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/ comorbidity.jsp for the coding algorithm; we modified the coding to include indicators for primary disease as well as comorbidities).

The analyses consisted of logistic regressions to determine the following: (1) the characteristics associated with treatment selection (PCI or CABG); and (2) the effect of CABG versus PCI on survival or time until the composite outcome of death, repeat revascularization, stroke, or subsequent AMI. All regressions controlled for patient characteristics and comorbidities. Results from the first logistic regression of procedure choice (CABG vs PCI) were used to construct a propensity score included as an additional covariate in the outcome regressions [8].

The outcomes analysis was limited to three years after the initial revascularization for which we had complete follow-up information for the full sample. This approach simplified the analysis by avoiding the need to make assumptions inherent in survival analysis techniques (eg, we avoided the proportional hazard assumption implicit in Cox regression, as this assumption was violated by the data). The three-year time period remains relevant for this older population as this population is subject to mortality from competing risks. A series of “stacked” logits using monthly outcomes were conducted using all observations free of the specified outcomes at the beginning of each month. For example, for the analysis of survival, the likelihood of surviving to the end of the first month after revascularization was estimated using all observations; subsequently the observations that remained alive at the end of the first month to estimate the (conditional) likelihood of surviving to the end of the second month, repeating this process 35 times. Each “monthly” logistic regression provided an estimate of surviving (ie, not dying, or not experiencing one of the four combined outcomes of death, repeat revascularization, stroke, or acute myocardial infarction) for persons receiving CABG versus PCI for multivessel disease. The logistic regression enabled the generation of survival curves for the two treatment strategies. Confidence intervals were generated from bootstrapping the survival estimates. To assess the relative impacts of patient characteristics and comorbidities, two additional logistic regressions were completed: one for the likelihood of surviving the first two months (“early” outcome) and a second regression for surviving to 36 months conditional upon surviving the first two months (“late” outcome). We present odds ratios for the patient characteristics and comorbidities to assess the relative effects on the likelihood of “early” versus “late” survival/freedom from death and the four combined outcomes.

Results

Sample characteristics at the time of the index admission (Table 1) demonstrate that based on bivariate t tests, CABG beneficiaries appear to be slightly younger, more likely to be male, have Part B deductible paid for by Medicaid. The CABG patients were less likely to have a number of medical-comorbid conditions: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), congestive heart failure (CHF), hypothyroidism, depression, hypertension with complications, or cancer. The first column of Table 2 provides the results for the logistic regression for procedure choice (CABG vs PCI). Patients were more likely to be selected for CABG if younger, male, and absent the following comorbidities: CHF, STEMI, depression, hypertension with complications, or cancer. Patients with electrolyte irregularities were more likely to receive CABG.

Table 1. Cohort Descriptive Statistics.

| Descriptor | Full Sample | CABG | PCI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of observations | 10,141 | 5,803 | 4,338 | |

| Beneficiary characteristics | ||||

| Age | 87.2 | 86.8 | 87.7 | 0.000 |

| Non-white | 5.2% | 5.1% | 5.3% | 0.722 |

| Male | 49.4% | 54.9% | 41.9% | 0.000 |

| State Medicaid buy-in | 8.2% | 6.7% | 10.2% | 0.000 |

| Comorbidities prior to index admission | ||||

| Prior stroke | 5.7% | 5.7% | 5.9% | 0.629 |

| CHF | 7.6% | 6.3% | 9.4% | 0.000 |

| Valvular disease | 4.1% | 3.9% | 4.4% | 0.283 |

| Conditions/comorbidities prior to/including index admission | ||||

| STEMI | 20.6% | 17.8% | 24.3% | 0.000 |

| Pulmonary circulatory disease | 3.6% | 3.6% | 3.6% | 0.976 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 14.5% | 15.0% | 13.8% | 0.097 |

| COPD | 18.4% | 18.9% | 17.8% | 0.164 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13.4% | 12.3% | 15.0% | 0.000 |

| Electrolyte irregularity | 22.1% | 25.0% | 18.3% | 0.000 |

| Depression | 3.5% | 3.1% | 4.0% | 0.010 |

| Hypertension with complications | 72.9% | 71.2% | 75.2% | 0.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 21.6% | 21.3% | 22.0% | 0.410 |

| Cancer | 3.7% | 3.3% | 4.3% | 0.013 |

| Anemia | 16.8% | 16.4% | 17.3% | 0.236 |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CHF = congestive heart failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 2. Adjusted Odds Ratios for Death and Composite Outcomes.

| Descriptor | CABG vs PCI (Propensity Score) | Death | Composite Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early (Death in 1–2 Months) | Late (Death by 36 Months if Alive at 3 Months) | Early (Poor Outcome in 1–2 Months) | Late (Poor Outcome by 36 Months if Alive at 3 Months) | ||

| Procedure | |||||

| CABG | 1.487a (1.345–1.646) | 0.608a (0.532–0.696) | 1.714a (1.550–1.895) | 0.837a (0.763–0.919) | |

| Beneficiary characteristics | |||||

| Age | 0.841a (0.008) | 1.075 (0.842–1.373) | 1.211 (0.978–1.499) | 1.113 (0.922–1.345) | 1.343b (1.050–1.718) |

| Non-white | 1.083 (0.106) | 1.133 (0.842–1.524) | 1.003 (0.785–1.283) | 0.847 (0.675–1.063) | 1.028 (0.798–1.325) |

| Male | 1.619a (0.070) | 0.764 (0.383–1.523) | 1.057 (0.578–1.934) | 0.689 (0.405–1.173) | 0.613 (0.308–1.223) |

| County of residence (reference: rural) | |||||

| Metropolitan | 0.993 (0.058) | 0.983 (0.831–1.162) | 1.176b (1.025–1.350) | 1.064 (0.942–1.203) | 1.017 (0.890–1.162) |

| Micropolitan | 0.996 (0.075) | 0.797 (0.634–1.001) | 1.064 (0.891–1.272) | 0.933 (0.794–1.096) | 0.928 (0.780–1.105) |

| State Medicaid buy-in | 0.707a (0.056) | 1.114 (0.646–1.921) | 1.965a (1.232–3.136) | 1.376 (0.907–2.086) | 1.848b (1.084–3.151) |

| Comorbidities prior to index admission | |||||

| Prior stroke | 0.996 (0.091) | 1.330b (1.038–1.704) | 1.328a (1.084–1.627) | 1.609a (1.345–1.926) | 1.551a (1.241–1.938) |

| CHF | 0.615a (0.053) | 1.921 (0.934–3.951) | 2.490a (1.328–4.669) | 1.586 (0.909–2.768) | 3.866a (1.883–7.939) |

| Valvular disease | 1.107 (0.125) | 1.228 (0.887–1.699) | 1.230 (0.930–1.625) | 1.059 (0.822–1.364) | 0.863 (0.635–1.174) |

| Conditions/comorbidities prior to/including index admission | |||||

| STEMI | 0.655a (0.034) | 2.210b (1.193–4.094) | 1.730b (1.008–2.969) | 2.048a (1.272–3.298) | 1.911b (1.029–3.547) |

| Pulmonary circulatory disease | 1.116 (0.127) | 1.110 (0.789–1.561) | 1.149 (0.863–1.531) | 1.061 (0.819–1.375) | 0.936 (0.688–1.274) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.100 (0.066) | 1.117 (0.898–1.388) | 1.117 (0.935–1.335) | 1.134 (0.966–1.331) | 1.149 (0.949–1.392) |

| COPD | 0.998 (0.055) | 1.242a (1.068–1.446) | 1.405a (1.244–1.588) | 1.033 (0.922–1.158) | 1.329a (1.172–1.507) |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.889 (0.055) | 0.723b (0.557–0.937) | 0.914 (0.744–1.123) | 0.876 (0.728–1.054) | 1.181 (0.950–1.469) |

| Electrolyte irregularity | 1.705a (0.090) | 1.622 (0.766–3.436) | 0.942 (0.491–1.806) | 1.045 (0.587–1.860) | 0.596 (0.283–1.253) |

| Depression | 0.767b (0.087) | 0.947 (0.570–1.573) | 1.533b (1.015–2.316) | 1.009 (0.691–1.473) | 1.917a (1.215–3.025) |

| Hypertension w/complication | 0.859a (0.042) | 0.590a (0.459–0.758) | 0.954 (0.768–1.185) | 0.856 (0.707–1.037) | 1.228 (0.966–1.561) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.955 (0.049) | 0.912 (0.771–1.079) | 1.451a (1.277–1.648) | 0.955 (0.847–1.076) | 1.441a (1.262–1.645) |

| Cancer | 0.674a (0.074) | 1.065 (0.558–2.034) | 2.308a (1.348–3.953) | 1.266 (0.777–2.062) | 2.759a (1.496–5.090) |

| Anemia | 1.032 (0.059) | 0.944 (0.795–1.121) | 1.173b (1.027–1.340) | 0.959 (0.847–1.086) | 1.004 (0.875–1.153) |

| Observations | 10,141 | 10,141 | 8,922 | 10,141 | 7,299 |

z-statistics in parentheses for the treatment choice logit (CABG vs PCI).

95% confidence interval in parentheses for the outcome equations.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.05.

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CHF = congestive heart failure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

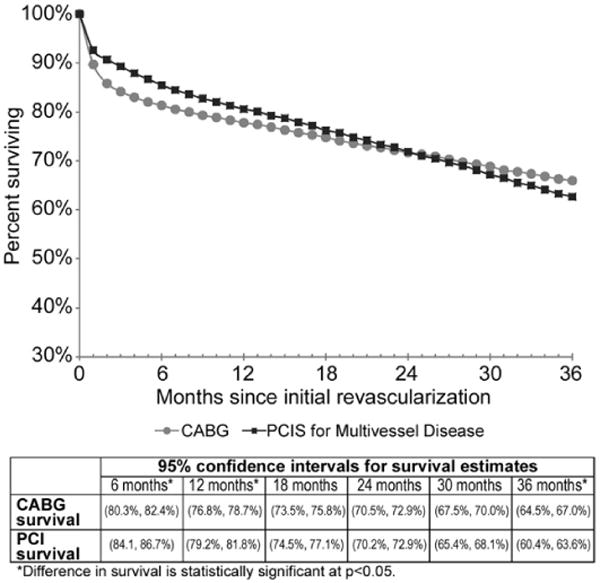

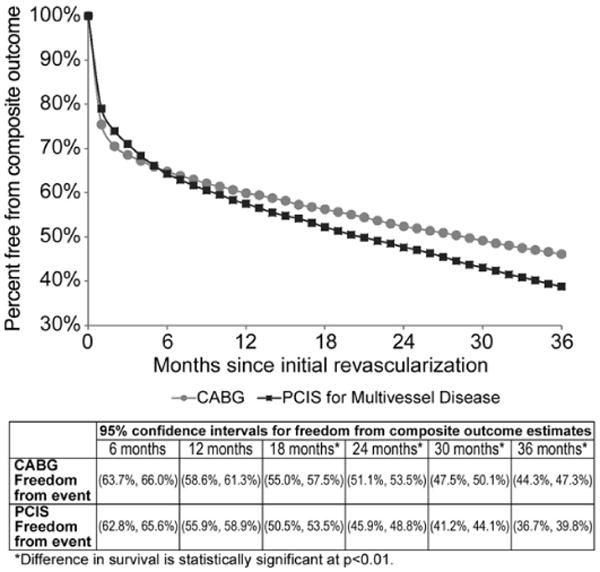

The monthly logistic regression identified lower survival (p < 0.01) for CABG recipients the first two months after primary revascularization, but CABG provided significantly better survival (p < 0.05) and freedom from the composite outcome at 36 months (p < 0.01). Monthly logistic regressions for adjusted outcomes (survival and freedom from composite outcome) are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. The adjusted survival curves cross in favor of CABG at roughly 24 months with a 3.3% advantage at three years (p < 0.05). Similarly, in the adjusted freedom from composite outcome cross in favor of CABG at approximately five months with a 7.3 percentage- point advantage at three years (p < 0.01). Both figures have 95% confidence intervals for the estimates of percent of patients surviving or free from composite outcome at six-month intervals.

Fig 2.

Adjusted survival with confidence interval for persons age 85 and older. (CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; p < 0.05.)

Fig 3.

Adjusted freedom from composite outcome (composite of death, repeat revascularization, stroke and acute myocardial infarction) for persons age 85 and older. (CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; p < 0.01.)

Because outcomes for CABG shifted from initially inferior to superior over time, the additional columns of Table 2 provide coefficients from the logistic regressions for the “early outcome” (death or composite outcome within the first two months after initial revascularization) and “late outcome” (death or composite outcome at 36 months conditional upon surviving or without composite outcome by two months post-revascularization). The odds ratios for the effect of PCI on death or composite outcome reinforce the findings that PCI recipients have lower likelihood of death or composite outcome early, but the likelihood of death or manifesting a composite outcome is greater at three years. The odds ratio in Table 2 also illustrates the effect of covariates.

In an attempt to understand factors associated with early (within two months of CABG) versus late mortality (two to 36 months post-CABG conditional upon survival to two months), a logistic regression was performed comparing documented descriptors (Table 3). Early CABG death was associated with increasing age, STEMI, prior stroke, preexisting CHF, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Late CABG mortality was associated with age, STEMI, prior stroke, preexisting CHF, COPD, diabetes and cancer. Time-dependent factors such as progression of pre-procedure CHF and cancer appear to be contributing to late CABG death.

Table 3. Factors Associated With Mortality Less Than Two Months After CABG Surgery.

| Factor | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.06 (1.02–1.20) | 0.004 |

| Male | 0.74 (0.63–0.87) | 0.000 |

| STEMI | 1.81 (1.51–2.16) | 0.000 |

| Prior stroke | 1.45 (1.07–1.97) | 0.017 |

| Preexisting CHF | 1.88 (1.40–2.51) | 0.000 |

| COPD | 1.32 (1.10–1.59) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 0.79 (0.65–0.97) | 0.023 |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CHF = congestive heart failure; CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

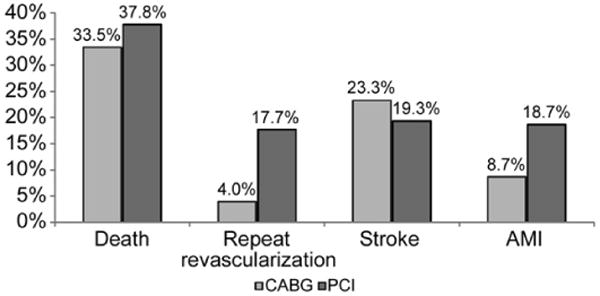

As morbidity associated with procedures is critical to very elderly patients for decision making, the breakdown of the composite endpoint (death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and subsequent revascularization) is of interest. Figure 4 provides information on the unadjusted rates of the four outcomes by three years after the initial revascularization. The outcomes are not mutually exclusive, as patients may have experienced more than one of the outcomes (eg, a patient may have suffered a stroke and then died) or may have experienced one of the outcomes more than once in the three years after the initial revascularization. Although the rate of stroke by 36 months was higher for persons revascularized by CABG, the rates of death, repeat revascularization, and recurrent AMI were lower at 36 months for patients initially receiving CABG versus PCI. Specifically, the rate of subsequent revascularizations was more than four times higher in the PCI group (17.7% vs 4.0%). The incidence of AMI was more than twice as frequent in the PCI group. All differences are significant (p < 0.01).

Fig 4.

Unadjusted 3-year composite outcomes (not mutually exclusive) for patients age 85 and older. (CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; p < 0.01 for all groups.)

Comment

This retrospective analysis of Medicare claims data provides evidence of three-year mortality and morbidity benefits of CABG in a large cohort of very elderly patients presenting with ACS and multivessel CAD. Rates of survival and freedom from composite morbidity are both initially higher for PCI recipients. Coronary artery bypass grafting provides enhanced survival and freedom from composite morbidity at 36 months relative to PCI. Comorbidities previously identified to negatively affect outcomes from CABG apply to this population as well; COPD, CHF, peripheral vascular disease, and STEMI. The size of the population studied, the availability of DES, and the broad demographic representation suggest that these findings are widely applicable in the current era. In appropriately selected very elderly ACS patients with multivessel CAD, CABG remains a viable strategy despite the availability of DES.

Given the improved survival and morbidity benefits over time for CABG versus PCI, an important question is whether the initial mortality risk of CABG, its postsurgical functional limitations, and its recovery period are worth the longer term survival advantage. Patients, especially persons over age 85, may be willing to discount additional months of life for the early benefits of PCI. Although this analysis prohibits an unambiguous recommendation for CABG versus PCI for any particular patient, the results provide evidence that CABG may be preferred and may provide improved outcomes for selected patients. Albeit speculative, the advantage of surgery may arise from a more complete revascularization strategy and (or) the durability advantages of left internal thoracic artery grafts. The Synergy between PCI with the Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial published a higher risk of stroke with CABG compared with left main PCI [9], and our results are consistent with this observation. The incidence of stroke was surprisingly high in both treatment groups with an increased incidence in CABG patients. It is possible that this analysis of very elderly patients has identified a particularly high-risk patient population that is highly vulnerable to cerebrovascular complications of coronary revascularization.

Interest in the elderly and the very elderly is growing, as they account for an increasing share of the US population. Unfortunately, prospective randomized controlled trials have excluded older patients, which limit insight into this vulnerable group. More recent trials such as the Trial of Invasive versus Medical therapy in Elderly (TIME) have enrolled a greater number of older patients [10] but the over-80-year-old group remains underrepresented. Alexander and colleagues [11] successfully used the National Cardiovascular Network to study cardiac surgery outcomes in octogenarians. This thoughtful analysis observed that appropriately selected octogenarians could successfully undergo cardiac surgery with acceptable risk. In a single-center review, Akins and colleagues [5] identified 600 consecutive octogenarians undergoing cardiac operations. They not only demonstrated reasonable five-year survival but also observed that at five years, survival normalized with the general US octogenarian population. Extending beyond the single-center experience to a regional analysis, the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group [7] evaluated 1,693 octogenarians undergoing PCI or CABG for multivessel disease. They identified a short-term advantage with PCI at six months with a long-term benefit of CABG over the subsequent eight-year follow-up. This retrospective regional study was followed by a large meta-analysis published by the Mayo Clinic essentially confirming the above and advocating for prospective randomized controlled trials to provide enhanced evidence [6]. Finally, the recently published SYNTAX trial is a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing CABG with multivessel PCI using exclusively DES [9]. The SYNTAX population had a mean age of 65 years and excluded AMI patients, and therefore differed substantially from the current study. Moreover, the cohort analyzed presently is substantially larger, with two additional years of follow-up. No randomized trials of myocardial revascularization are currently planned in the 85-and-older population, which increases the importance of observational studies to provide data from real-world clinical practice to aid decision making.

Despite these strengths, this study has several limitations. It is a retrospective administrative analysis without clinical records such as ejection fraction. As medical record data were unavailable, the comorbidity data reflect only those codes included on the MedPAR claims and may underestimate the true prevalence of comorbid disease in the population due to missing data or important unobserved health status measures. Administrative data may also over-represent new conditions such as stroke. While propensity score adjustment of the treatment groups for comorbidities and other clinical and demographic characteristics improves the precision of these results, unmeasured differences may persist and result in significant confounding. Additional factors, including onset of comorbidities over time, socioeconomic status, support systems, premorbid functional status, and hospital and health care providers, may have influenced treatment selection beyond the controlling influence of the propensity adjustment methodology. Although unavailable, this study would also benefit from outcomes data specifying functionality (activities of daily living and self-report questionnaire) as well as a cost analysis.

In very elderly patients with ACS and multivessel CAD, CABG appears to offer an advantage over PCI of survival and freedom from composite endpoint at three years. To optimize the benefit of CABG in very elderly patients requires the absence of significant CHF, lung, and peripheral vascular disease. Despite improved safety of PCI and the development of drug-eluting stents, the advantage of CABG (albeit modest) over PCI appears to persist even after age 85. Improved patient selection, enhanced surgical techniques, and postprocedural care sensitive to the unique physiology in this vulnerable population will ensure that CABG remains an important therapeutic option for the treatment of multivessel CAD in this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants 1R01AG025801 and 2T32GM008719.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CHF

congestive heart failure

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DES

drug-eluting stents

- MedPAR

Medicare Provider Analysis and Review

- OR

odds ratios

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- RCT

randomized controlled trials

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarct

Footnotes

Presented at the Fifty-sixth Annual Meeting of the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, Marco Island, FL, Nov 4–7, 2009.

References

- 1.Johnson WM, Smith JM, Woods SE, Hendy MP, Hiratzka LF. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: does age alone influence outcomes? Arch Surg. 2005;140:1089–93. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.11.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson ED, Alexander KP, Malenka DJ, et al. Multicenter experience in revascularization of very elderly patients. Am Heart J. 2004;148:486–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Booth J, Clayton T, Pepper J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of coronary artery bypass surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: six-year follow-up from the Stent or Surgery Trial (SoS) Circulation. 2008;118:381–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serruys PW, Ong AT, van Herwerden LA, et al. Five-year outcomes after coronary stenting versus bypass surgery for the treatment of multivessel disease: the final analysis of the Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study (ARTS) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:575–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akins CW, Daggett WM, Vlahakes GJ, et al. Cardiac operations in patients 80 years old and older. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:606–15. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00615-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKellar SH, Brown ML, Frye RL, Schaff HV, Sundt TM., 3rd Comparison of coronary revascularization procedures in octogenarians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:738–46. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dacey LJ, Likosky DS, Ryan TJ, Jr, et al. Long-term survival after surgery versus percutaneous intervention in octogenarians with multivessel coronary disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1904–11. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfisterer M, Buser P, Osswald S, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary artery disease with an invasive vs optimized medical treatment strategy: one-year results of the randomized TIME trial. JAMA. 2003;289:1117–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander KP, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, et al. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients > or = 80 years: results from the National Cardiovascular Network. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:731–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]