Abstract

Background

Mutations in the gene coding for transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI) have been identified in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Mutations coincided with immunodeficiency in families, suggesting dominant inheritance.

Objective

Because most subjects with CVID have no immunodeficient family members and heterozygous mutations predominate, the role of TACI mutations in sporadic CVID is unclear.

Methods

TACI was sequenced from the genomic DNA of 176 subjects with CVID and family members. B cells of subjects with or without mutations were examined for binding to the ligand, a proliferation inducing ligand (APRIL), and for proliferation and immunoglobulin production after ligand

Results

Heterozygous TACI mutations were found in 13 subjects (7.3%). Six with mutations (46%) had episodes of autoimmune thrombocytopenia, in contrast with 12% of 163 subjects without mutations; splenomegaly and splenectomy were significantly increased (P = .012; P = .001.) B cells of some had impaired binding of APRIL and on culture with this ligand were defective in proliferation and immunoglobulin production; however, this was not different from B cells of subjects without mutations. Eight first-degree relatives from 5 families had the same mutations but were not immune-deficient, and their B cells produced normal amounts of IgG and IgA after APRIL stimulation.

Conclusion

Mutations in TACI significantly predispose to autoimmunity and lymphoid hyperplasia in CVID, but additional genetic or environmental factors are required to induce immune deficiency.

Clinical implications

Additional causes of this common immune deficiency syndrome remain to be determined.

Keywords: Common variable immune deficiency, TACI, B cell, IgG, IgA, immune thrombocytopenia purpura, splenectomy

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is a heterogeneous primary immunodeficiency disease characterized by low levels of serum IgG, IgA, and/or IgM, antibody deficiency, and recurring infections.1–4 Mutations in the B cell–activating factor (BAFF) receptor gene or the gene (TNFRSF13B) encoding the transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI) have been identified in 7% to 10% of subjects.5–8 TACI is expressed on mature B cells, and activation leads to T-cell–dependent and T-cell–independent responses and isotype switch.9–11 However, TACI signaling also plays an inhibitory role, because knockout mice have B-cell hyperplasia, increased immunoglobulin production, autoimmunity, splenomegaly, and B-cell lymphomas.12–14 B cells of subjects with CVID with homozygous mutations had in vitro proliferation defects and impaired immunoglobulin production when cultured with the ligands BAFF and a proliferation inducing ligand (APRIL).5,6 One mutation in the extracellular domain (C104R) leads to a disruption of a cysteine-rich region important for ligand binding.15,16 In addition, transfected mutants bearing C104R dominantly interfered with TACI signaling in vitro,17 perhaps explaining how some mutations described in CVID appeared to be inherited in a dominant fashion.5,6,18 However, because at least 90% of subjects with CVID do not have immune-deficient family members,2 the role of TACI mutations in subjects with sporadic inheritance is unclear. Some of the TACI mutations identified occur at a low frequency in healthy donors,5,19 further complicating the association with immune deficiency. In this study, we examined a large population of subjects with CVID for mutations in TACI to assess immunologic and clinical phenotypes associated with mutations and to evaluate the effect of specific heterozygous mutations in patients and carrier family members on B-cell function.

METHODS

Patients and blood samples

We studied 176 patients with CVID from Mount Sinai Medical Center1 enrolled in an Institutional Review Board–approved study of B-cell defects. These subjects were 90% white, aged 17 to 85 years. Of these, 166 had no family history of immune deficiency; 10 others were from 7 families in which other members had either CVID or IgA deficiency. First-degree family members of subjects with CVID with TACI mutations were also tested.

DNA and cDNA sequencing

Peripheral blood cells or B cells from EBV B-cell lines were lysed, genomic DNA was isolated, and cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription. The 5 exons of TNFRSF13B were PCR-amplified by using primers hybridized to intronic sequences. PCR products were isolated and DNA amplicons sequenced and aligned to the wild-type sequence by using standard methods.5,6 These results were compared with results for anonymous DNA samples obtained with informed consent from 100 unrelated healthy individuals of mixed ethnic backgrounds.

B cells and APRIL binding

EBV B-cell lines were established from PBMCs and kept in culture in complete medium (RPMI 1640 medium with 20% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine.) To assess binding of APRIL, B cells were incubated with 200 ng/mL megaAPRIL (FLAG-APRIL Axxora, San Diego, Calif) for 30 minutes on ice in the presence of 1 μL heparin (1000 U/mL); 1 μg/mL biotin-anti FLAG monoclonal M2 antibody (Sigma, St Louis, Mo) was added for 30 minutes, and the cells were washed and examined by using streptavidin-phycoerythrin (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif) gating on CD19+ cells (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif).

APRIL-induced B-cell proliferation

PBMCs were suspended in prewarmed PBS/0.5% BSA at 1 × 106/mL, and 1 μL 5 mmol/L stock carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif) was added for a concentration of 5 μmol/L to assess cell proliferation.20 Cells were incubated for 5 minutes, washed 3 times with 0.5% BSA/PBS, and incubated with megaAPRIL (200 ng/mL; Axxora) with or without IL-10 (10 ng/mL; R&D, Minneapolis, Minn). Positive controls were CD40L (300 ng/mL; Axxora) + IL-10, or in some cases, 0.6 μg/mL CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 2006 (InvivoGen, San Diego, Calif). Cultures were continued for 5 to 7 days. After this, cells were collected, washed, and analyzed for cell divisions by using flow cytometry with 488-nm excitation and emission filters appropriate for fluorescein.

APRIL-induced immunoglobulin production

Peripheral mononuclear cells were incubated with megaAPRIL (200 ng/mL) with or without IL-10 (10 ng/mL) or CD40-ligand (300 ng/mL) plus IL-10 for 10 days in complete medium. Cell supernatants were tested for IgG and IgA content by using ELISA reagents (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, Tex).

Statistical analysis

Significance of TACI mutations and the presence of autoimmunity, splenectomy, or splenomegaly between patient groups with or without these mutations was explored by using χ2 testing.

RESULTS

Patients and mutational analyses

Thirteen unrelated white, non-Hispanic subjects with CVID, aged 17 to 66 years (8.3%), had heterozygous TACI mutations. Ten had single and 3 had compound heterozygous mutations, including 2 with different stop codons (Table I). The mutations included some previously described (C104R, A181E, S144X, S194X) as well as new ones: R72H, L171R, and C172Y (included in Pan-Hammarstrom et al19). These subjects had no known family members with immune defects, and none of the 10 patients from 7 families with immune deficient family members had mutations.

TABLE I.

Clinical information and immunoglobulin levels on patients with mutations*

| Patient no. | Sex | Age (y) | Mutation | Clinical | IgG§ | IgA | IgM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 62 | C104R | ITP*, splenomegaly, splenectomy | 251 | <6 | 27 |

| 2 | M | 46 | C172Y | Frequent URI, chronic otitis media, hearing loss | 490 | 18 | 33 |

| 3 | F | 44 | C104R S194X |

AIHA/Coombs positive anemia ×3, ITP ×3; numerous pneumonias; pulmonary infiltrates, splenomegaly; splenectomy | 200 | <6 | 24 |

| 4 | F | 44 | L171R A181E |

URIs, arthritis, Sweet syndrome, pneumonia, aseptic meningitis | 392 | 59 | 6 |

| 5 | F | 58 | C104R S144X |

Urticaria and angioedema, allergies/joint pain | 332 | 48 | 14 |

| 6 | F | 66 | A181E | Juvenile RA, rheumatic fever, microscopic colitis pneumonia, sinusitis, otitis, cardiac valve replacement, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, ITP, anti-IgA Ab | 594 | <7 | 34 |

| 7 | F | 43 | C104R | Seizure disorder, colitis, sinusitis | 164 | <5 | 5 |

| 8 | F | 50 | R72H | Recurrent URI, sinusitis, pneumonia, breast cancer | 293 | 110 | 90 |

| 9 | M‡ | 45 | C104R | ITP, pan-sinusitis, pneumonia ×4; granulomatous skin disease | <7 | <7 | 6 |

| 10 | F | 41 | C104R | ITP, lymphadenopathy, granulomatous infiltrates, neutropenia, splenomegaly, splenectomy | 475 | 47 | 54 |

| 11 | F | 17 | A181E | Sinusitis, myringotomy tubes | 371 | 14 | 4 |

| 12 | F | 26 | A181E | Granulomatous lesions skin, lungs: fibronodular infiltrates, arthritis, ITP, splenomegaly, splenectomy, diarrhea/uveitis AIHA/Coombs positive anemia | 164 | 5 | 20 |

| 13 | F | 67 | C104R | Chronic sinusitis, bronchitis, chronic rectal herpes simplex | 530 | 11 | <5 |

Of the 176 subjects with CVID, 30 (17%) had an exon five P251L single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), and 7 others had V220A SNP, both found previously in normal subjects. In 2 of the subjects with CVID, the P251L SNP was homozygous. (These subjects are not considered further here.)

ITP, Immune thrombocytopenia purpura; AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; F, female; JRA, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis; M, male; ND, not done; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; URI, upper respiratory tract infections.

X-linked agammaglobulinemia excluded by genetic analysis of Btk.

Before immunoglobulin replacement: serum immunoglobulins (mg/dL); normal ranges for adults: IgG, 694–1618; IgA, 81–463; IgM, 48–271 mg/dL; IgG1, 344–966; IgG2,133–622; IgG3,12–138; IgG4, 1–115 mg/dL.

Autoimmunity and clinical complications

Six (46%) of the subjects with mutations had significant splenomegaly and 1 or more episodes of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP); 4 had undergone splenectomy (31%; Table I). Other autoimmune/inflammatory conditions included autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), granulomatous disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, uveitis, and psoriasis. For 163 subjects with CVID without mutations, 20 had a history of ITP, 17 had splenomegaly, 8 had splenectomy, and 6 had AIHA. Comparing subjects with CVID with and without mutations, these differences were significant: ITP, P = .012; splenomegaly, P = .012; and splenectomy, P = .001.

Immunologic functions

The immunologic phenotypes of these patients, even those with mutations in the same codon, were diverse. B-cell numbers, baseline levels of serum immunoglobulins, and antibody function ranged from absence of B cells, IgG, IgA, and IgM, and no antibody in some, to increased numbers of B cells, more normal serum immunoglobulin levels, and retention of some antibody production in others (see this article’s Table E1 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). IgA levels were normal in 1 and detectable in 6 others; a few produced some level of antibody to pneumococcal serotypes. For 3 subjects (patient 6, A181E; patients 7 and 10, both with C104R mutations), a decline in serum IgG and IgM had occurred over a period of 4 to 18 years before immunoglobulin replacement was instituted (see this article’s Table E2 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). The decline in serum immunoglobulin levels, increasing numbers of infections, and lack of functional antibody led to the institution of immunoglobulin therapy.

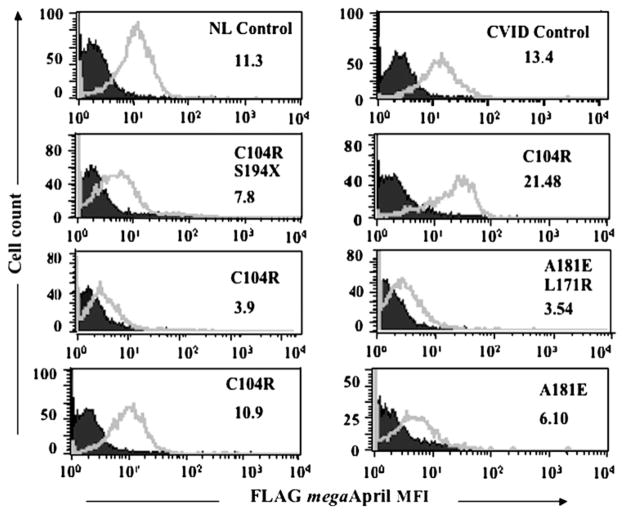

Heterozygous mutations may lead to impaired APRIL binding

Homozygous C104R mutations prevent the binding of APRIL.5,6 Here we tested B cells of 4 unrelated subjects with heterozygous C104R mutations (Fig 1). Although cells of 2 of these subjects demonstrated normal ligand binding, B cells of the other 2 had reduced or almost absent affinity for APRIL. Reduced ligand binding was also found for B cells of 2 other subjects with transmembrane mutations (A181E and A181E/L174R), showing that heterozygous TACI mutations can also impair receptor ligand interactions.

FIG 1.

Heterozygous mutations may lead to reduced ligand binding. B cells (EBV cell lines) of subjects with TACI mutations indicated were tested to determine the binding of APRIL in comparison with the controls indicated. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI, x-axis) for B cells (cell counts, y-axis) is shown. Isotype controls are marked in closed areas, surface APRIL fluorescence in open areas. NL, Normal.

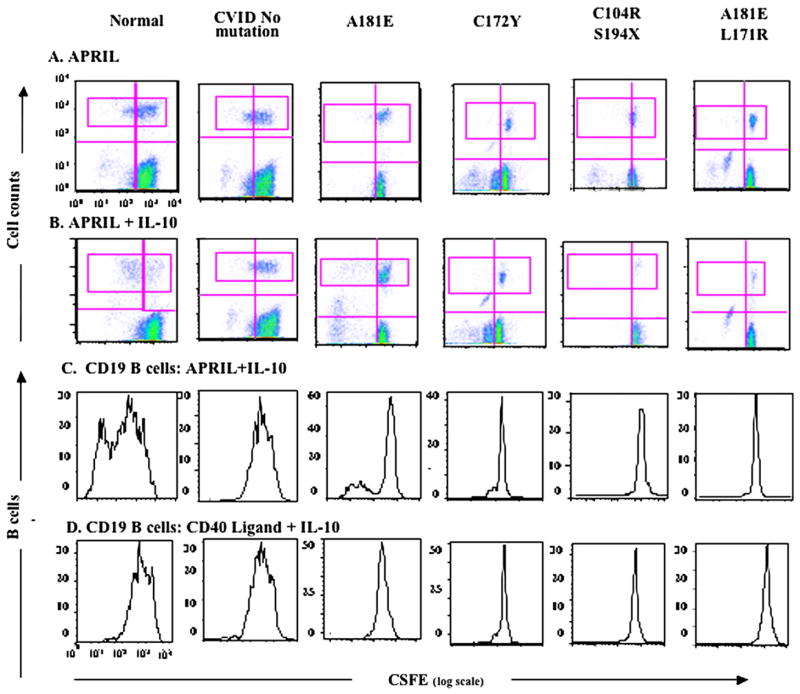

APRIL and B-cell proliferation

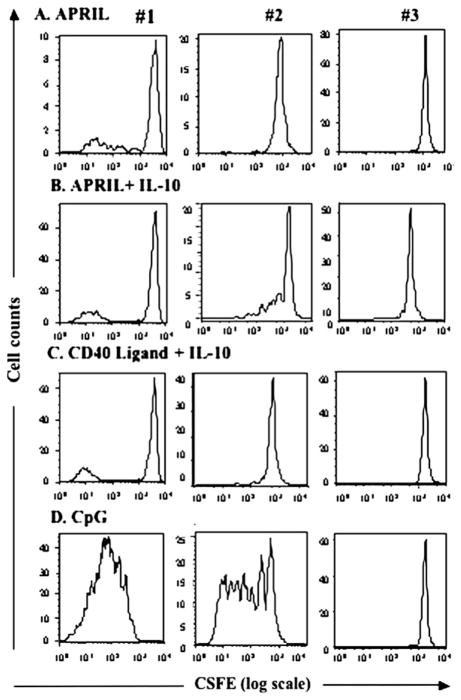

B cells of subjects with CVID with homozygous TACI mutations were shown to proliferate poorly in the presence of APRIL.5 For subjects with CVID with heterozygous mutations, proliferation of cells cultured with APRIL gave variably abnormal results; however, they were not clearly distinguishably different from cells of subjects with CVID without TACI mutations, many of whom had poor responses to this ligand (as well as other cell activators). Fig 2 shows results for 1 normal control, a subject with CVID with some proliferative responses, and 4 subjects with mutant TACI proteins. B cells of the subject with a A181E mutation showed some response to APRIL+ IL-10; cells of another with a different transmembrane mutation, C172Y, showed little or no proliferation, although his cells also did not respond to CD40L + IL-10. Both subjects with compound heterozygous mutations demonstrated similarly poor proliferative responses to APRIL with or without IL-10, and also CD40L. We also compared the cell proliferative capacities of 3 subjects with the same mutation, C104R (Fig 3). Although B cells of subject 1 demonstrated some B-cell proliferation when cultured with APRIL or APRIL + IL-10 and to control stimulators CD40L + IL-10 and CpG DNA, cells of subject 2 had some response to APRIL + IL-10 and CpG-DNA but not to APRIL alone or CD40L + IL-10. Cells of subject 3 were unresponsive to all stimulators. Thus the intrinsic cellular dysfunction in CVID makes it difficult to determine the degree to which specific heterozygous TACI mutations impair cell proliferation.

FIG 2.

APRIL-induced proliferation of B cells. Cells were stained with CFSE (log scale, x-axis, wavelength, 492 nm) and cultured with indicated stimulators for 6 days; y-axis = cell counts. A and B, Non-B and nondividing cells = dense population at the lower right of each panel. The CD19+ B-cell population is indicated (top pink rectangle). C and D, CFSE-stained B-cell populations.

FIG 3.

Proliferation of B cells of subjects with C104R TACI mutations. As for Fig 2, proliferation of CFSE (x-axis)–labeled B cells of 3 unrelated subjects with CVID with C104R mutations were compared by using stimulators shown. y-axis = cell counts. A, APRIL alone. B, APRIL + IL-10. C, CD40 ligand + IL-10. D, CpG.

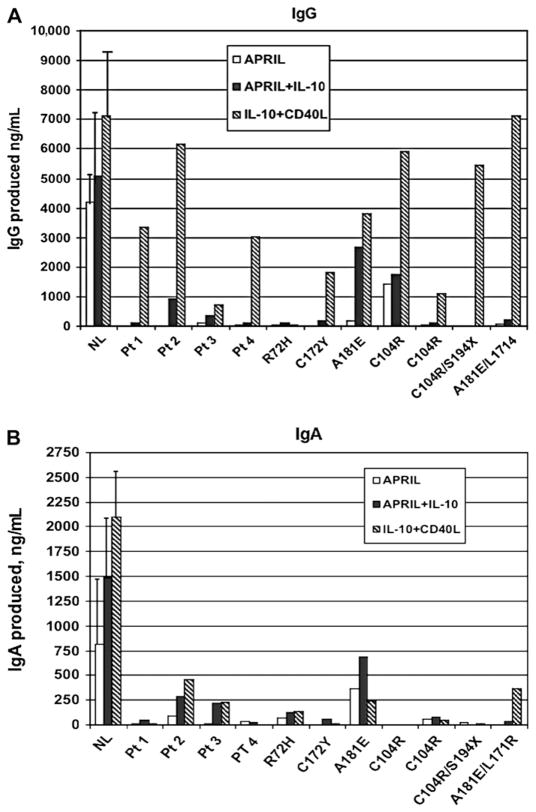

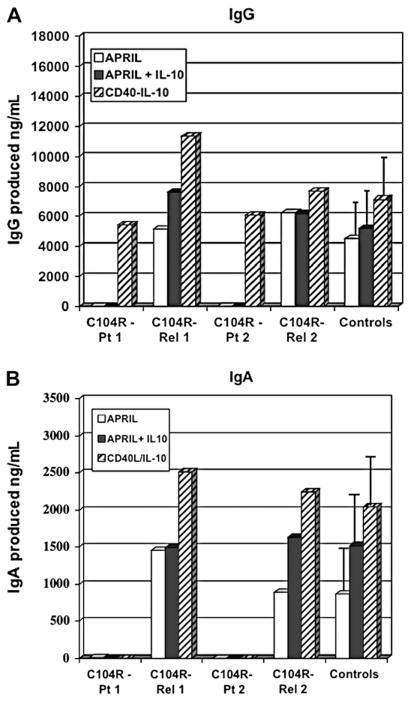

APRIL-induced IgG and IgA production

To investigate APRIL-induced immunoglobulin production, peripheral B cells of subjects with CVID with TACI mutations were compared with cells of subjects with no mutations and healthy controls. B cells of normal controls produced IgG (Fig 4, A) and IgA (Fig 4, B) when incubated with APRIL and APRIL + IL-10 or CD40L + IL-10. Although B cells of subjects with CVID cultured with CD40L + IL-10 did produce some IgG (but less IgA) compared with normal controls, B cells of subjects 1 to 4 with CVID (no mutations) were at least as dysfunctional as B cells of subjects with CVID with single heterozygous mutations R72H, C172Y, A181E, or C104R, or compound heterozygous mutations (C104R/S194X, and L171R/A181E) in this system.

FIG 4.

IgG and IgA production. Peripheral blood cells of subjects were cultured as shown to assess IgG (A) or IgA (B) production (ng/mL); values minus baseline levels. Four subjects with CVID (no mutations) and 8 subjects with the heterozygous mutations shown are compared or are indicated, ng/mL (y-axis). Results for 8 normal controls are given as means (± SEs). NL, Normal; Pt, patient.

Family studies

DNA samples of first-degree relatives of subjects in Table I were examined to determine the inheritance of the TACI mutations and to determine whether an immune deficiency was found in carrier relatives (see this article’s Table E3 and Fig E1 in the Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Eight parents, siblings, or children, aged 9 to 77 years, from 5 families had the same heterozygous mutations as the index patients; all had normal serum immunoglobulins, and none had significant ongoing medical illness. To examine in vitro immunoglobulin production of relatives, peripheral B cells of subjects with CVID and relatives with the same mutation were examined (Fig 5, A and B). Although the subjects with CVID had very little IgG or IgA production, relatives with the same heterozygous C104R mutation had normal immunoglobulin production. These studies suggest that the sheer presence of this mutation does not impair this B-cell response.

FIG 5.

Immunoglobulin production for normal relatives. As for Fig 4, peripheral blood cells of subjects (#3 C104R patient [Pt], and #10 C104R Pt 2) and their first-degree relatives with the same mutation (C104R Rel-1, C104R Rel-2) were tested for IgG (A) and IgA (B) production. The amounts of IgG or IgA over baseline are given in ng/mL (y-axis). The median (± SE) is shown for 8 normal controls.

DISCUSSION

One of the more puzzling aspects of CVID has been the highly variable immunologic and clinical phenotype in what is considered a genetic defect.2,3,21 Recent studies have implicated the mutations in the tumor necrosis family members BAFF-receptor and TACI.5,6,21 In mice, BAFF and its receptor are responsible for B-cell survival and maturation22; APRIL appears required for T-cell independent antibody responses and isotype switch.6 The observation that mutations in TACI are associated with CVID suggests that TACI signaling is also important for normal B-cell function in human beings.5,6,21 However, the in vitro abnormalities of ligand binding, cell proliferation, and immunoglobulin production in response to APRIL or BAFF were most clearly demonstrated for subjects with CVID with homozygous TACI mutations, although the inheritance of the immune defect was associated with the presence of a single mutant allele.5,6 Because approximately 90% of subjects with CVID do not have family members with immune defects,2,3 the role of heterozygous TACI mutations in producing or contributing to B-cell dysfunction is unclear.

Salzer et al5 found that 10 (7.4%) of 135 subjects with sporadic CVID had heterozygous mutations in TACI, and 1 had a homozygous mutation. We tested 176 subjects with CVID; 13 (7.3%) had mutations, none of these had a family history of immune deficiency, and none of our 10 familial cases had TACI mutations. TACI knockout mice have deficient responses to vaccination with T independent antigens12; however, subjects with CVID with heterozygous mutations had a widely varied ability to respond to pneumococcal vaccine, ranging from absent to some antibody production. Although signaling via TACI may facilitate immunoglobulin class switch,9,23 B cells of some subjects with heterozygous TACI mutations had varying levels of serum IgA, and B cells of one of these subjects produced more IgA in vitro than subjects with CVID with no mutations, when cultured with APRIL.

The TACI receptor is composed of trimers or higher-order oligomers; the effect of a heterozygous mutation would depend on the complex assembly, ligand binding, downstream signaling, and the requirements for a sufficient number of functioning receptors.12,22 The extracellular mutation (C104R) prevents binding of BAFF and APRIL,5,6,16 and in the presence of wild-type TACI acts as a dominant-negative in nuclear factor-κB activation,17 suggesting how dominant inheritance in families might arise. We show that the same heterozygous mutation in cells of 4 unrelated subjects with CVID, as well as trans-membrane mutations, produces variably reduced ligand binding. B cells of subjects with CVID with homozygous TACI mutations were shown to have reduced or absent immunoglobulin production when cultured with APRIL.5 However, B cells of patients proliferate poorly and have reduced immunoglobulin production in vitro when exposed to many stimulators24–27; we could not attribute impaired in vitro functions solely to heterozygous mutations in TACI, especially because relatives with the same mutations had normal serum immunoglobulin levels and in vitro immunoglobulin secretion. The effect of APRIL on B cells is known to be complex, because heparin sulfate proteoglycans such as CD44 and syndecan 1, expressed on B cells, may provide effective APRIL binding partners, inducing cell proliferation, class switch recombination, and immunoglobulin production.28–30 However, current understanding of how APRIL signals via TACI and this third receptor does not explain how heterozygous mutations in TACI can be associated with immune deficiency and autoimmunity in patients but not in heterozygous normal relatives. It may be pertinent that 3 of the subjects with TACI mutations were originally IgA-deficient or mildly hypogammaglobulinemic and had falling serum IgG and IgM levels over a period of years. Although in these cases the mutation in TACI was clearly congenital, the full immune defect appeared to develop only with time.

In addition to the function TACI plays in amplifying humoral immunity, the functioning of this receptor includes a regulatory role. TACI knockout mice have expanded numbers of B cells, lymphoid hyperplasia, splenomegaly, and autoimmunity, and a significant percent develop lymphoma.14 Six of 19 subjects with TACI mutations previously reported had splenomegaly. Similar to one of these subjects who had homozygous S144X,5 our patient with compound heterozygous mutations (C104R and S194X) had medical complications reminiscent of the TACI knockout mouse, with lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, 3 episodes of AIHA, and severe and recurrent ITP requiring rituxan and finally splenectomy.14,31 The highly significant prominence of autoimmunity and lymphoid hypertrophy in subjects with CVID with mutations in TACI suggests that abnormal receptor signaling might interfere with appropriate suppression of B-cell proliferation and/or self-reactivity. In keeping with the confirmed suppressive effect of TACI signaling on B cells, activation of the TACI intracellular domain induces apoptosis.14 Agonistic TACI-specific antibodies also inhibit BAFF-driven and CD40-enhanced IgG production by human B cells, indicating that the sequence of these signals in B-cell differentiation is crucial.10 Several of these stages are known to be abnormal in CVID, because there is a preponderance of naive B cells,31,32 impaired B-cell responses to basic signals,33 and insufficient expression of CD40L.26

A related immunologic and clinical phenotype exists for another TNF receptor family (CD95, FAS), mutations of which lead to autoimmune lymphoproliferative disease. Although the majority of subjects have heterozygous mutations, this defect is inherited as an autosomal-dominant trait with incomplete penetrance; family members with the same mutation do not necessarily exhibit autoimmunity, lymphadenopathy, or splenomegaly.34 However, similar to TACI mutations in CVID, the development of the phenotype may depend on a second signal, still unknown genetic or environmental influences.

We conclude that heterozygous mutations in TACI found in CVID may lead to impaired ligand binding and contribute to defects in cell activation, but the connection between heterozygous mutations and hypogammaglobulinemia is not clear, because normal relatives may have the same mutations without evidence of immune deficiency. We suggest that abnormal or deficient TACI receptor signaling may promote the autoimmune/lymphoproliferative phenotype observed in so many of these subjects.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI 101093, AI-467320, AI-48693) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Contract 03-22; and U19 AI0167152 and AR043274 to T.W.B. and N01-AI-30070 to B.G.

Abbreviations

- AIHA

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- APRIL

A proliferation inducing ligand

- BAFF

B cell–activating factor

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- CVID

Common variable immunodeficiencyl

- ITP

Immune thrombocytopenia purpura

- TACI

Transmembrane activator and calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand interactor

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: C. Cunningham-Rundles is on advisory boards for OMRIX and Talacris and has received grants/research support from the National Institutes of Health. T. W. Behrens is an employee of Genentech. B. Grimbacher has received grants/research support from DFG, USIDnet, and the European Union. J. Bussel is on advisory boards for Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Baxter; has stock or other equity ownership in Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline; has received grants/research support from Amgen, Biogen-IDEC, Cangene, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sysmex; and is on the speakers’ bureau for Baxter. The rest of the authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Conley ME, Notarangelo LD, Etzioni A. Diagnostic criteria for primary immunodeficiencies. Representing PAGID (Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiencies) Clin Immunol. 1999;93:190–7. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:34–48. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham-Rundles C. Common variable immunodeficiency. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2001;1:421–9. doi: 10.1007/s11882-001-0027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapel H, Geha R, Rosen F. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;132:9–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salzer U, Chapel HM, Webster AD, Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Schmitt-Graeff A, Schlesier M, et al. Mutations in TNFRSF13B encoding TACI are associated with common variable immunodeficiency in humans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:820–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castigli E, Wilson SA, Garibyan L, Rachid R, Bonilla F, Schneider L, et al. TACI is mutant in common variable immunodeficiency and IgA deficiency. Nat Genet. 2005;37:829–34. doi: 10.1038/ng1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salzer U, Grimbacher B. Monogenetic defects in common variable immunodeficiency: what can we learn about terminal B cell differentiation? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:377–82. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000231906.12172.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldacker S, Warnatz K. Tackling the heterogeneity of CVID. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:504–9. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000191888.97397.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castigli E, Wilson SA, Scott S, Dedeoglu F, Xu S, Lam KP, et al. TACI and BAFF-R mediate isotype switching in B cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:35–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakurai D, Kanno Y, Hase H, Kojima H, Okumura K, Kobata T. TACI attenuates antibody production costimulated by BAFF-R and CD40. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:110–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litinskiy MB, Nardelli B, Hilbert DM, He B, Schaffer A, Casali P, et al. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:822–9. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Bulow GU, van Deursen JM, Bram RJ. Regulation of the T-independent humoral response by TACI. Immunity. 2001;14:573–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan M, Wang H, Chan B, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Baker T, et al. Activation and accumulation of B cells in TACI-deficient mice. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:638–43. doi: 10.1038/89790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seshasayee D, Valdez P, Yan M, Dixit VM, Tumas D, Grewal IS. Loss of TACI causes fatal lymphoproliferation and autoimmunity, establishing TACI as an inhibitory BLyS receptor. Immunity. 2003;18:279–88. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallweber HJ, Compaan DM, Starovasnik MA, Hymowitz SG. The crystal structure of a proliferation-inducing ligand, APRIL. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hymowitz SG, Patel DR, Wallweber HJ, Runyon S, Yan M, Yin J, et al. Structures of APRIL-receptor complexes: like BCMA, TACI employs only a single cysteine-rich domain for high affinity ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7218–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garibyan L, Lobito AA, Siegel RM, Call ME, Wucherpfennig KW, Geha RS. Dominant-negative effect of the heterozygous C104R TACI mutation in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1550–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI31023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan-Hammarström Q, Du L, Björkander J, Cunningham-Rundles C, Nelson DL, Salzer U, et al. Mutations in TNFRSF13B encoding TACI and selective IgA deficiency. Nat Genet. 2007 doi: 10.1038/ng0407-429. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Salzer U, Du L, Bjorkander J, Cunningham-Rundles C, Nelson DL, et al. Reexamining the role of TACI coding variants in common variable immunodeficiency and selective IgA deficiency. Nat Genet. 2007;39:429–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0407-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyons BA. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243:147–54. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammarstrom L, Vorechovsky I, Webster D. Selective IgA deficiency (SIgAD) and common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:225–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackay F, Schneider P, Rennert P, Browning J. BAFF AND APRIL: a tutorial on B cell survival. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:231–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castigli E, Scott S, Dedeoglu F, Bryce P, Jabara H, Bhan AK, et al. Impaired IgA class switching in APRIL-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3903–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307348101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North ME, Spickett GP, Allsop J, Webster AD, Farrant J. Defective DNA synthesis by T cells in acquired “common-variable” hypogammaglobulinaemia on stimulation with mitogens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;76:19–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer MB, Hauber I, Eggenbauer H, Thon V, Vogel E, Schaffer E, et al. A defect in the early phase of T-cell receptor-mediated T-cell activation in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Blood. 1994;84:4234–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrington M, Grosmaire LS, Nonoyama S, Fischer SH, Hollenbaugh D, Ledbetter JA, et al. CD40 ligand expression is defective in a subset of patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1099–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kondratenko I, Amlot PL, Webster AD, Farrant J. Lack of specific antibody response in common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) associated with failure in production of antigen-specific memory T cells. MRC Immunodeficiency Group. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:9–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-993.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingold K, Zumsteg A, Tardivel A, Huard B, Steiner QG, Cachero TG, et al. Identification of proteoglycans as the APRIL-specific binding partners. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1375–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bischof D, Elsawa SF, Mantchev G, Yoon J, Michels GE, Nilson A, et al. Selective activation of TACI by syndecan-2. Blood. 2006;107:3235–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurai D, Hase H, Kanno Y, Kojima H, Okumura K, Kobata T. TACI regulates IgA production by APRIL in collaboration with HSPG. Blood. 2007;107:2961–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-041772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan M, Marsters SA, Grewal IS, Wang H, Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Identification of a receptor for BLyS demonstrates a crucial role in humoral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:37–41. doi: 10.1038/76889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agematsu K, Futatani T, Hokibara S, Kobayashi N, Takamoto M, Tsukada S, et al. Absence of memory B cells in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2002;103:34–42. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham-Rundles C, Radigan L, Knight AK, Zhang L, Bauer L, Nakazawa A. TLR9 activation is defective in common variable immune deficiency. J Immunol. 2006;176:1978–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Worth A, Thrasher AJ, Gaspar HB. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome: molecular basis of disease and clinical phenotype. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:124–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.05993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]