Abstract

The relative TONs of productive and nonproductive metathesis reactions of diethyl diallylmalonate are compared for eight different ruthenium-based catalysts. Nonproductive cross metathesis is proposed to involve a chain-carrying ruthenium methylidene. A second more-challenging substrate (dimethyl allylmethylallylmalonate) that forms a trisubstituted olefin product is used to further delineate the effect of catalyst structure on the relative efficiencies of these processes. A steric model is proposed to explain the observed trends.

The widespread application of olefin metathesis in various fields of chemical synthesis has fueled the continued search for transition metal catalysts that exhibit high reactivity, selectivity, and stability.1 Studies have described the effect on reactivity upon modifying every ligand of ruthenium-based catalysts. Generally, activity is reported as yield or turnover number (TON) for the reaction of a substrate of interest, which does not account for nonproductive metathesis events.

The role of nonproductive metathesis in the cross metathesis (CM) of terminal olefins has been studied in detail for early hetero- and homogeneous molybdenum and tungsten catalysts.2 In general, the rate of degenerate metathesis greatly exceeds that of the productive metathesis reactions and evidence suggests the chain-carrying intermediate is a metal alkylidene (M=CHR), not a methylidene (M=CH2). Thus, the TON determined from the amount of product formed is less than the total number of metathesis events that the catalyst has accomplished. An efficient catalyst must perform many turnovers and be selective for productive pathways. Although degenerate reactions do not result in a net change in concentration of the catalyst or the substrate, they can provide additional opportunities for catalyst decomposition, and therefore can decrease efficiency. Recently, Hoveyda and Schrock reported that degenerate processes in asymmetric ring-closing metathesis (RCM) reactions are both prevalent and key to achieving high levels of enantioselectivity.3

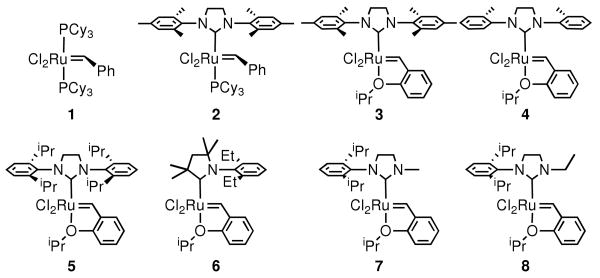

While measuring conversion of substrate is a common and straightforward method of assessing catalyst activity in olefin metathesis, and other catalytic reactions, degenerate metathesis reactions must also be assayed in order to provide a more complete picture of catalyst efficiency. No data on the rates of degenerate processes are available for modern ruthenium-based catalysts (Chart 14), or for RCM reactions. Herein we report studies aimed at understanding the relative rates of degenerate and productive metathesis reactions.

Chart 1.

Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalysts.

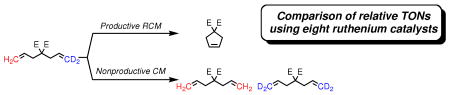

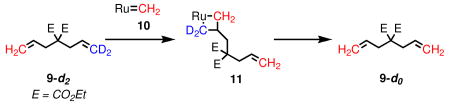

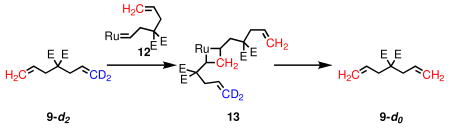

Diethyl diallylmalonate (9) and allylmethallylmalonate (15) have become benchmark substrates for evaluation of olefin metathesis catalysts in RCM.5 Besides the productive pathway, there are at least two potential nonproductive pathways. The first begins with a ruthenium methylidene (10), and forms a β-substituted metallacycle (11); breakdown of this intermediate regenerates the starting material, but exchanges the methylene termini (eq 1). Alternatively, methylene exchange could take place via a α,α-disubstituted metallacycle (13) by coordination of a substrate molecule to ruthenium alkylidene 12 (eq 2).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

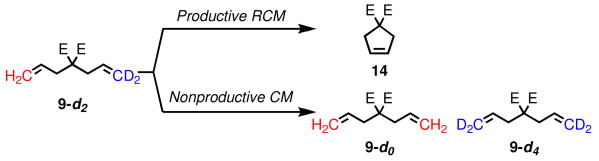

To investigate these productive and nonproductive pathways, diethyl d2-diethyldiallylmalonate (9-d2) was prepared and subjected to catalysts 1-8. The conversion to cyclopentene 14 was monitored by GC, while degenerate metathesis reactions were monitored by the appearance of 9-d0 and 9-d4 by TOF-MS (Scheme 1).6,7

Scheme 1.

Assay for Nonproductive RCM of 9.

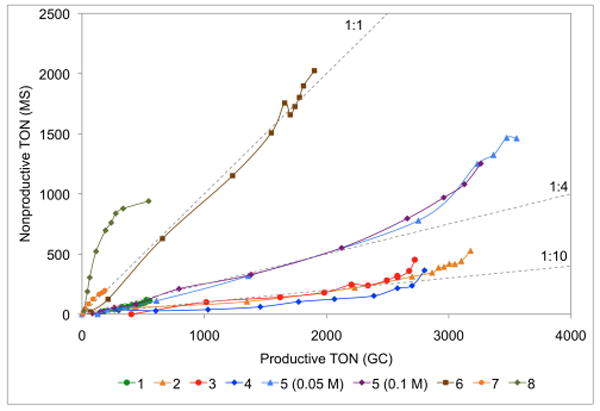

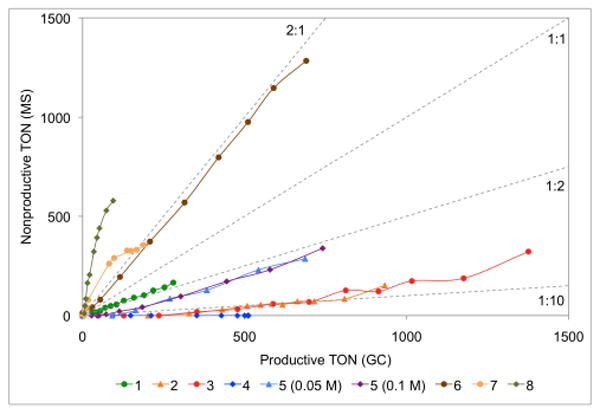

Figure 1 shows the degenerate TON versus productive TON. Surprisingly, significant levels degenerate events were detected with many catalysts. NHC-bearing catalysts 2-4 display degenerate:productive ratios of approximately 1:10, while 5, which catalyst containing the bulky 2,6-diisopropylphenyl (DIPP) substituent, is closer to 1:4. Cyclic alkylaminocarbene (CAAC)-containing catalyst 6 catalyzes nearly equal number of degenerate and productive metathesis events, as well as N-alkyl catalysts 7-8.

Figure 1.

Plot of nonproductive versus productive conversion for the RCM reaction shown in Scheme 1. Reaction conditions were 50 °C in toluene (1 mL) with substrate (0.1 mmol) and catalyst (1 – 1000 ppm, 2, 3, 4, 5 – 250 ppm, 6 – 500 ppm, 7 – 5000 ppm, 8 – 1000 ppm).

Catalyst 5 was evaluated at two concentrations, and no change in the ratio of degenerate to productive metathesis events was detected; this is highly suggestive that nonproductive metathesis events are catalyzed by a methylidene species (eq 1), as the alternative mechanism (eq 2) is second order in substrate, and would be expected to have some concentration dependence.

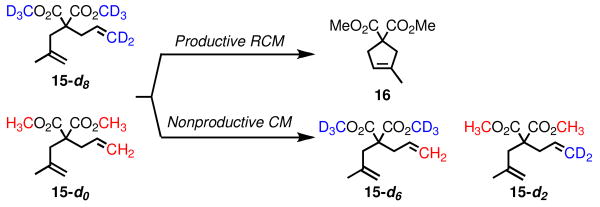

To evaluate the significance of degenerate metathesis in the RCM of a more challenging substrate, deuterated dimethyl allylmethallylmalonate 15-d8 was prepared. A mixture of this isotopomer and the per-protio compound (15-d0) was prepared, and subjected to catalysts 1-8 (Scheme 2). Nonproductive metathesis was measured via TOF-MS by monitoring the appearance of 15-d6 and 15-d2. Again, NHC catalysts 2-4 perform the fewest degenerate events – in fact almost none were detected with 4 (Figure 2). Bulky NHC-bearing complex 5 and diphosphine catalyst 1 perform around one degenerate event for every two productive turnovers. Catalysts 6-8, however, perform two or more nonproductive reactions for every productive RCM event. As in the RCM of 9, no concentration dependence on the ratio of degenerate to productive turnovers was detected with catalyst 5.

Scheme 2.

Assay for Nonproductive RCM of 15.

Figure 2.

Plot of nonproductive TON versus productive TON for the RCM reaction shown in Scheme 2. Reaction conditions were 50 °C in toluene (1 mL) with substrate (0.1 mmol) and catalyst (1 – 1000 ppm, 2, 3, 4, 5 – 250 ppm, 6 – 500 ppm, 7 – 5000 ppm, 8 – 1000 ppm).

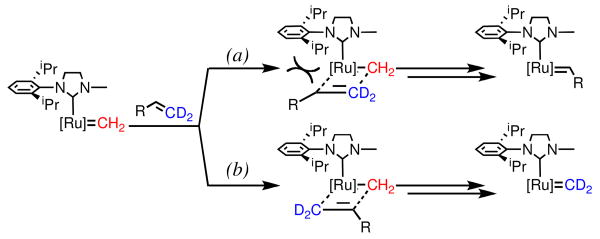

From these two datasets, it is plausible to propose that sterics is the overriding determinant of the relative rates of degenerate to productive events. Specifically, a catalyst bearing an unsymmetric carbene ligand with significantly different-sized groups will favor degenerate metathesis pathways (e.g., CMe2 vs. N-2,6-Et2Ph in 6, N-Me vs. N-2,6-iPr2Ph in 7, N-Et vs. N-2,4,6-Me3Ph in 8). Scheme 3 illustrates this model beginning with the methylidene derived from catalyst 7. Coordination of a terminal olefin can proceed in two possible regiochemistries: the first generates an α-substituted metallacycle (path a), and results in the formation of an alkylidene that ultimately leads to a productive turnover event; the second generates a β-substituted metallacycle (path b), which exchanges the olefin termini, but does not generate a molecule of product. The nonproductive pathway is especially facile with catalysts 6-8 due to the absence of any significant steric interactions between the ligand and the approaching olefin en route to the β-substituted metallacycle. Catalysts with symmetric and bulky groups (e.g., N-2,6-iPr2Ph on both sides of 5) would experience similar interactions along path a, but increased steric repulsion along path b – resulting in fewer nonproductive events and thus higher overall efficiency.

Scheme 3.

Steric Model for Ligand Effect on Nonproductive Metathesis.

Herein we have described the study of nonproductive reactions in ring-closing metathesis using ruthenium catalysts. The number of nonproductive events in relatively simple substrates is strikingly high, but comparable with early work on hetereogeneous systems. The steric model proposed can be applied to other important metathesis processes where selectivity is important.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The NIH (K99GM084302 to ICS, 5RO1GM31332 to RHG) for generous financial support, Hosea Nelson and Brian M. Stoltz (Caltech) for assistance with and use of their TOF-MS instrument, and Scott Virgil (Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis) for assistance with automation and analytical equipment.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and details of quantitative analysis.

References

- 1.Grubbs RH. Handbook of Metathesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2003. and references cited therein. Hoveyda AH, Zhugralin AR. Nature. 2007;450:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06351.Schrodi Y, Pederson RL. Aldrichimica Acta. 2007;40:45–52.Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:4490–4527. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500369.Grubbs RH. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7117–7140.Furstner A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2000;39:3013–3043.

- 2.(a) Casey CP, Tuinstra HE. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:2270–2272. [Google Scholar]; (b) Casey CP, Tuinstra HE, Saeman MC. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:608–609. [Google Scholar]; (c) Handzlik J. J Mol Cat A. 2004;218:91–100. [Google Scholar]; (d) McGinnis J, Katz TJ, Hurwitz S. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:605–606. [Google Scholar]; (e) Tanaka K, Takeo H, Matsumura C. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2422–2425. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meek SM, Malcolmson SJ, Li B, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16407–16409. doi: 10.1021/ja907805f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For the original report of catalysts 1-6 used in this study, see, respectively: Schwab P, Grubbs RH, Ziller JW. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:100–110.Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Org Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q.Kingsbury JS, Harrity JPA, Bonitatebus PJ, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:791–799.Stewart IC, Ung T, Pletnev AA, Berlin JM, Grubbs RH, Schrodi Y. Org Lett. 2007;9:1589–1592. doi: 10.1021/ol0705144.Courchay FC, Sworen JC, Wagener KB. Macromolecules. 2003;36:8231–8239.Anderson DR, Lavallo V, O'Leary DJ, Bertrand G, Grubbs RH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:7262–7265. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702085.

- 5.(a) Ritter T, Hejl A, Wenzel AG, Funk TW, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2006;25:5740–5745. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuhn KM, Bourg JB, Chung CK, Virgil SC, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5313–5320. doi: 10.1021/ja900067c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Note that exchanges of olefin termini that do not result in a change in isotopic composition are also occurring. For a complete discussion of how degenerate TONs were calculated see the Supporting Information. Kinetic isotope effects are beyond the scope of the current discussion.

- 7.For a discussion on the reversibility of the RCM reaction, see the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.