Abstract

Early loss of proteoglycan 4 (PRG4), a lubricating glycoprotein implicated in boundary lubrication, from the cartilage surface has been associated with degeneration of cartilage and early onset of osteoarthritis. Viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid and other macromolecules has been proposed as a treatment of osteoarthritis, however efficacy of viscosupplementation is variable and may be influenced by the short residence time of lubricant in the knee joint after injection. Recent studies have demonstrated the use of aldehyde (CHO) modified extracellular matrix proteins for targeted adherence to a biological tissue surface. We hypothesized that CHO could be exploited to enhance binding of lubricating proteoglycans to the surface of PRG4 depleted cartilage. The objective of this study was to determine the feasibility of molecular resurfacing of cartilage with aldehyde modified PRG4. PRG4 was chemically functionalized with aldehyde (PRG4-CHO), and aldehyde plus Oregon Green (OG) fluorophore (PRG4-OG-CHO) to allow for differentiation of endogenous and exogenous PRG4. Cartilage disks depleted of native PRG4 were then treated with solutions of PRG4, PRG4-CHO, or PRG4-OG-CHO and then assayed for the presence of PRG4 by immunohistochemistry, ELISA, and fluorescence imaging. Repletion of cartilage surfaces was significantly enhanced with the inclusion of CHO compared to repletion with unmodified PRG4. These findings suggest a generalized approach that may be used for molecular resurfacing of tissue surfaces with PRG4 and other lubricating biomolecules, perhaps leading in the future to a convenient method for overcoming loss of lubrication during the early stages of osteoarthritis.

Keywords: cartilage, PRG4, aldehyde, biolubrication

1. Introduction

Articular cartilage is a stratified connective tissue located at the ends of long bones that normally provides a load-bearing, low friction, wear-resistant surface. The compressive modulus of cartilage increases with depth from the articular surface and directly correlating with GAG content [1]. In the superficial zone, which corresponds to the uppermost 10% of the total cartilage thickness, the cells have a flattened morphology, are organized in clusters parallel to the articular surface [2], and exist at a high cell density compared to deeper zones [3]. Upon damage due to disease, injury or as a consequence of aging, articular cartilage possesses limited capacity for self-repair [4, 5]. Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common degenerative joint disease, begins with superficial fibrillation [6] and can result in extensive degeneration and eventual loss of cartilage.

The zonal organization of cartilage has implications for the biomechanical properties of the tissue. Boundary lubricants encoded by the gene PRG4 [7] include the protein products Superficial Zone Protein (SZP) [8, 9], secreted by chondrocytes of the superficial zone [9]; synoviocytes [8, 9], and meniscal cells [10]; lubricin [11], abundant in synovial fluid [12]; megakaryocte stimulating factor [13]; and proteoglycan 4 (PRG4). These highly homologous molecules are thought to contribute to the low friction properties of articular cartilage and can collectively be referred to as PRG4 [14]. The role of PRG4 as a boundary lubricant is supported by its presence at the surface of articular cartilage [9], its abundance in synovial fluid, its mutated form resulting in camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa varapericaritis syndrome [15], and its reduction of the friction coefficient when applied between natural and artificial materials [16–19]. In addition, expression and localization of PRG4 was found to be down-regulated in several animal models of OA [20–23] suggesting a relationship between loss of PRG4 and pathogenesis of OA.

Current clinical strategies for treating osteoarthritis include intra-articular hyaluronic acid (HA) viscosupplementation. Efficacy of viscosupplementation is variable [24, 25] and may be influenced by the short residence time of HA in the knee joint after injection[24]. Further, treatment of rat knee joints with injections of recombinant lubricin[26], which bound to the cartilage surface, has indicated chondroprotective effects during the progression of OA [27], suggesting the benefits of lubricating molecules in the knee joint as a possible therapy for OA. While promising, one drawback of this potential treatment is the lack of semi-permanent adhesion to the cartilage surface, similar to current viscosupplementation treatments. Approaches that enhance the presence of lubricating biomolecules at the tissue surface may offer advantages by increasing the biolubricant concentration at the boundary layer.

Recent studies have established chemical modification of extracellular matrix proteins with aldehyde (CHO) groups as a viable approach for adhering biomolecules to a tissue surface. Chondroitin sulphate, one of the main extracellular matrix components in cartilage, was multifunctionalized with methacrylate and aldehyde groups in order to generate a bioadhesive which could be used for cartilage integration[28] [29]. We hypothesized that functionalization of lubricating biomolecules with CHO would enhance binding to the surface of PRG4 depleted cartilage. Thus, the objectives of this study were to prepare aldehyde modified PRG4 (PRG4-CHO), and to determine whether the presence of CHO enhances immobilization of PRG4 to articular cartilage tissue surfaces.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cartilage Harvest

Cartilage disks (6 mm diameter; ~0.3 mm thick, representing ~15% of the total cartilage thickness) were harvested from the patellofemoral groove and femoral condyles of bovine calve stifle joints (Research 87, Boylston, MA) using aseptic technique. Disks were cut to include the intact articular surface.

2.2. Cartilage Culture and PRG4 Purification

Cartilage disks were incubated in medium (low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 0.4 mM L-proline, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B) supplemented with 0.01% bovine serum albumin, 10 ng/ml human transforming growth factor-β1, and 25 μg/ml ascorbic acid [30]. Disks were cultured for 12–19 days with culture medium collected every three days. PRG4 was purified as previously described [9, 30]. Briefly, pooled culture medium was fractionated by anion-exchange chromatography. The sample was applied on DEAE-Sepharose, previously equilibrated with 0.15M NaCl, 0.005M EDTA, and 0.05M sodium acetate, pH 6.0. The 0.3–0.6M eluate was collected, concentrated with a Centricon Plus 100 kDa MW cutoff filter, and then quantified for protein content by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Presence of PRG4 protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis using monoclonal antibody 4D6. Samples (0.5 μg of total PRG4 per lane) were separated on a 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gel by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred overnight to a polyvinyl difluoride membrane. The membrane was probed with mAb 4D6 using ECL Plus detection system (GE BioSciences, Piscataway, NJ). Production of monoclonal antibody 4D6 was directed against purified PRG4 at the Monoclonal Antibody Facility at Northwestern University (Chicago, IL). Mouse hybridoma cell lines secreting PRG4-specific antibody were generated and then purified (data not shown).

2.3. Chemical Modification of PRG4

PRG4 was chemically modified with aldehyde only (PRG4-CHO) or both aldehyde and Oregon Green (PRG4-OG-CHO) as shown in Figure 1. OG functionalization was employed to distinguish between applied (exogenous) and native (endogenous) PRG4. PRG4-CHO was prepared by modifying PRG4 with succinimidyl 4-formylbenzamide (Solulink, San Diego, CA hereafter referred to as CHO) at a PRG4:CHO molar ratio of 1:1000 in 100 mM PO4 buffer, pH 8.5, overnight at 4°C with shaking. To prepare PRG4-OG-CHO, purified PRG4 in solution was combined with Oregon Green 488 carboxylic acid, succinimidyl ester (OG-SE, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) at a PRG4:OG molar ratio of 1:100 and agitated for 3 hours at room temperature. Excess and unreacted OG-SE was removed by illustra NAP-5 column purification (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). PRG4-OG was then modified as described above with S-4FB (PRG4-OG:CHO molar ratio of 1:1000 in 100 mM PO4 buffer, pH 8.5) overnight to yield PRG4-OG-CHO. Samples were then gel purified with NAP-5 column. In all reactions, excess amounts of small molecule linkers were applied in order to ensure complete modification of PRG4 with OG and/or CHO. Reaction of PRG4 with OG, PRG4-OG with CHO, or PRG4 with CHO was confirmed by gel electrophoresis and fluorescence gel imaging (unpublished data). Final concentrations of PRG4-CHO and PRG4-OG-CHO samples were measured by BCA assay and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and SYPRO Ruby Red Stain (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), as previously described [9]. Finally, all sample concentrations were adjusted to be 450 μg/ml, the approximate concentration of PRG4 in synovial fluid obtained from bovine calf knees [31]. Modification substitution ratio (MSR) of CHO was determined using 2-hydrazinopyridine-2HCl assay (Solulink, San Diego, CA).

Figure 1.

Chemical modification of PRG4 with Oregon Green (OG) and aldehyde (CHO). Purified PRG4 was reacted with succinimidyl ester of Oregon Green 488 carboxylic acid, or succinimidyl-4-formylbenzamide (S-4FB), generating PRG4-OG or PRG4-CHO, respectively. A portion of PRG4-OG was further reacted with S-4FB to generate PRG4 conjugated with both OG and CHO (PRG4-OG-CHO).

2.4. Surface Modification of Cartilage with PRG4, PRG4-CHO, and PRG4-OG-CHO

Cartilage disk surfaces (6 mm diameter) were depleted of endogenous PRG4 prior to surface modification with chemically modified PRG4. The disks were first swabbed with 10% SDS, and then subsequently incubated in 1% SDS solution for 24 hours at room temperature with nutation (Figure 2) [31]. As a control, some cartilage disks were not depleted of PRG4 and were instead incubated in PBS. After 24 hours, the depleted and non-depleted cartilage disks were rinsed with PBS (six 10-min rinses), then incubated with 100 μl of PBS or PRG4 solutions (PRG4, PRG4-CHO, PRG4-OG-CHO at 450μg/ml) for 24 hours with agitation at 4°C (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic of methods used to investigate surface modification of cartilage disks with chemically modified PRG4.

Effects of surface modification on chondrocyte viability were assessed by viability assay (Live/Dead™ assay, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Freshly harvested cartilage disks were either left unmodified (t=0) or incubated in modification solution (PRG4, PRG4-CHO, and PRG4-OG-CHO at 450 ug/ml in complete DMEM media) for 20 hours (t=20 h) at 37°C. Disks were then transferred to Live/Dead™ staining solution for 20 minutes, rinsed in PBS, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Live/Dead analysis confirmed that surface modification did not affect chondrocyte viability (94±1.8%).

2.5. PRG4 Analyses

The amount of PRG4 repleted on the cartilage surface was qualitatively visualized by immunohistochemistry analyses and quantified in 4M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) extracts by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

PRG4 Quantification

Three modified or unmodified cartilage disks were incubated in 800 μl 4M GuHCl, 0.02M Tris, pH 8.2 (with proteinase inhibitors: 0.005M Benzamide HCl, 0.01 M N-ethylmaleimide, 0.005 M disodium EDTA, and 0.001 phenylmethylsulfonulfluoride) with nutation overnight at 4°C [10]. The disks were removed and extract solutions were saved for analysis. An ELISA for PRG4 in the extract solution was performed essentially as described previously [10]. Briefly, extract samples, as well as PRG4 standard samples, were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane with a Bio-Dot apparatus, reacted with mAb 4D6, followed by reaction with anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody with rinses of PBS-0.1% Tween between steps. Sample areas were removed from the membrane with a 6 mm diameter dermal punch, transferred to individual wells in a 48 well plate, and reacted with 2.2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) substrate (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The optical density of reaction solutions was then read on a spectrophotometer (Tecan Safire I, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 405 nm. Amounts of PRG4 were calculated using a purified PRG4 standard.

Visualization of Modified Cartilage Surfaces

Portions of unmodified and modified cartilage disks were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Samples were rinsed in PBS, embedded in OCT compound, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen cooled isopentane, and stored at −20°C until further analysis. Vertical cryosections (10 μm) were reacted with mAb 4D6, or as a negative control mouse IgG (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and detected with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Results were documented using phase and fluorescence microscopy using a Leica DM IRB microscope (Leica Microsystems, McHenry, IL) equipped with a SPOT RT camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Fluorescence micrographs were obtained for both green (Oregon Green) and red (rhodamine detected PRG4) fluorescence color channels.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Effects of surface treatment of PRG4 at the cartilage surface and on CHO substitution efficiency was assessed by ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of PRG4

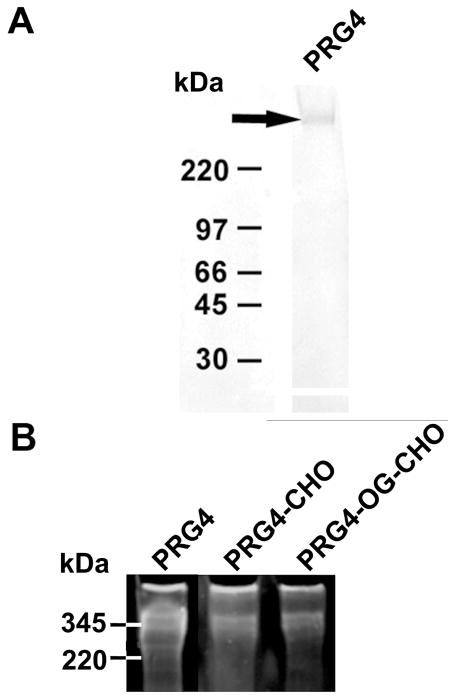

Immunoreaction of PRG4 with mAb 4D6 revealed a major band at approximate molecular weight of 345 kDa (Fig. 3A). Chemically modified PRG4 (PRG4-CHO) and (PRG4-OG-CHO) were also visualized at 345 kDa (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Characterization of PRG4. (A) Western blot of purified PRG4 probed with mAb 4D6 after separation on a 4–15% gradient polyacrylamide gel. A band was visualized at ~345 kDa. (B) PRG4 (non-functionalized), PRG4-CHO, and PRG4-OG-CHO were visualized by Ruby Red fluorescent stain gel at ~345 kDa.

CHO and OG-CHO were conjugated to PRG4 effectively. An aldehyde assay revealed similar levels of CHO modification of PRG4 (83 CHO per PRG4) and PRG4-OG (121 CHO per PRG4).

3.2. Surface Modification of Cartilage with PRG4, PRG4-CHO, and PRG4-OG-CHO

Chemical functionalization of PRG4 with CHO enhanced the concentration of PRG4 adherent to the cartilage surface (Fig. 4). Samples depleted of PRG4 with SDS treatment had 2.2-fold less PRG4 compared to unreacted (control) samples (p<0.05) (0.2±0.1 vs. 0.5±0.1 μg/cm2), and 2.7-fold less PRG4 than samples repleted with non-functionalized PRG4 (1.1±0.2 μg/cm2, p<0.05). In addition, SDS-treated samples had 5.0-fold less PRG4 at the surface compared to samples repleted with PRG4-CHO (p<0.001), or PRG4-OG-CHO (p<0.001). Samples repleted with non-functionalized PRG4 had similar amounts of PRG4 at the surface (0.6±0.1 μg/cm2) compared to unreacted (control) samples (0.5±0.1 μg/cm2, p=0.9). The amount of PRG4-CHO or PRG4-OG-CHO on the cartilage surface was 2.0-fold higher (1.1±0.2 μg/cm2) than samples treated with non-functionalized PRG4 (p<0.05). PRG4-CHO and PRG4-OG-CHO adhered to the cartilage surface in similar amounts (p=0.9).

Figure 4.

PRG4 content of native cartilage (white), cartilage depleted of native PRG4 by SDS treatment (gray), and cartilage repleted with PRG4 (striped), PRG4-CHO squares), and PRG4-OG-CHO (black). Mean±SEM, n= 4–6, (▲) p<0.001, (●) p<0.01, (◆) p<0.05.

Immunolocalization of PRG4 in cartilage disks agreed qualitatively (representative images presented in Figure 5) with the aforementioned quantitative results. PRG4 was visualized at the surface of control samples (Fig. 5CDE-i), as well as in superficial cells near the articular surface, but was absent from cartilage samples treated with SDS (Fig. 5CDE-ii). Depleted samples which were further repleted with PRG4 (Fig. 5CDE-iii), PRG4-CHO (Fig. 5CDE-iv), or PRG4-OG-CHO (Fig. 5CDE-v) showed presence of PRG4 at the surface. In particular, PRG4-CHO and PRG4-OG-CHO treated surfaces exhibited intense staining for PRG4 (Fig. 5E-iv, E-v respectively). Labeling with OG fluorophore indicated PRG4 at surfaces modified with PRG4-OG-CHO to be from applied (exogenous) PRG4 (Fig. 5D-v), distinct from native PRG4. PRG4-OG-CHO at the surface was also detectable by probing with mAb 4D6 (Fig. 5-v). Some PRG4 was also localized near the cartilage surface in disks which treated with PRG4-CHO and PRG4-OG-CHO. For all groups, cartilage disks probed with nonspecific IgG antibody did not exhibit staining for PRG4 (Fig. 5A-i:B-v).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical localization of PRG4 at the articular surface in (A-i:E-i) no reaction (control), (A-ii:E-ii) SDS dissociated, or (A-iii:E-iii) PRG4, (A-iv:E-iv) PRG4-CHO, or (A-v:E-v) PRG4-OG-CHO repleted samples. Cartilage sections were probed with (C-i:E-v) mAb 4D6 or (A-i:B-v) non-specific mouse IgG. Images were grouped as (i) no reaction, (ii) SDS dissociated, or (iii) PRG4, (iv) PRG4-CHO, (v) PRG4-OG-CHO repleted samples. The letters (A–E) were used to denote the imaging field of view, i.e., IgG phase, IgG rhodamine, PRG4 phase, PRG4 OG, PRG4 rhodamine, for the aforementioned groupings. Bar = 0 μm.”

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that aldehyde modification of PRG4 significantly enhances the amount of PRG4 bound to the cartilage surface. PRG4 was first isolated from media used to culture cartilage disks and identified with monoclonal antibody 4D6. Purified PRG4 was then modified with CHO or CHO and OG in order to distinguish applied chemically modified PRG4 from native PRG4 in subsequent PRG4 repletion studies. Western blot analysis confirmed immunoreaction of PRG4 with mAb 4D6 (Figure 3A). Ruby Red analysis (Figure 3B) indicated presence of PRG4 protein in chemically modified samples. Biochemical quantification (Figure 4) of PRG4 depleted cartilage disks after immersion in PRG4 solution demonstrated the presence of PRG4 at the cartilage surface, with the highest PRG4 levels being observed for repletion with CHO functionalized PRG4, regardless of whether OG fluorophore was present. These results agreed with qualitative immunohistochemical results (Figure 5). PRG4-OG-CHO was primarily localized at the cartilage surface (Figure 5), indicting successful application of PRG4 at the surface. A small amount of OG was observed very close to the cartilage surface (Figure 5D-v), likely unreacted OG (not conjugated to PRG4).

Increased repletion of PRG4 at the articular surface by chemically functionalized PRG4 suggests a contribution to surface attachment by a chemical mechanism. Succinimidyl 4-formylbenzamide (S-4FB) reacted with primary amines available in PRG4 to obtain aldehyde (CHO) functionalized PRG4 (PRG4-CHO). CHO groups on the resulting PRG4-CHO conjugate were likely utilized in attachment to the cartilage surface via coupling to amines present in extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins of cartilage and thus leading to formation of Schiff bases (Figure 6) [32]. While the stability of Schiff bases is generally dependent on the availability of a reductive agent[28, 33, 34], formation of Schiff bases can also favored at physiological pH [28] [29] and thus, less likely to be converted into advanced glycation endproducts [35]. In previous studies, CHO functionalized chondroitin sulfate was employed for sealing corneal incisions[29] and for cartilage integration [28]. While Schiff base formation with ECM components of the cartilage is likely the dominant reaction product of PRG4-CHO, the formation of PRG4 aggregates could also occur via intermolecular reactions with available lysine and cysteine residues on other PRG4 conjugates to form dimers and multimers [26, 36]. In addition, unmodified amine groups on PRG4-CHO conjugates or unmodified PRG4 may interact electrostatically with carboxyl groups available in the extracellular matrix. However, this potential mechanism is less likely to contribute to the overall binding of PRG4 to the cartilage surface since unmodified PRG4 was shown to replete cartilage surfaces to a significantly lesser extent compared to chemically functionalized PRG4.

Figure 6.

Potential mechanism of PRG4-CHO modification of the articular cartilage surface (not drawn to scale). A. PRG4-CHO conjugates react via Schiff base formation with primary amines present in ECM components of the cartilage surface. B. PRG4-CHO may bind to the tissue surface as monomers (i) or as multimeric complexes formed in solution by intermolecular Schiff base formation (ii, iii).

Previous studies have indicated the importance of the secondary structure of PRG4 in binding to the articular cartilage surface [26, 31]. Disruption of PRG4 binding was observed when cartilage surfaces were reduced and alkylated, thereby breaking disulfide bonds [26, 31]. However, in this study, the secondary structure of PRG4 was likely preserved, since prior studies have indicated that chemical functionalization of proteins with CHO maintains protein functionality [28]. Although kinetics of molecular interactions are likely to be temperature dependent[37] and repletion experiments carried out at 4°C may differ from those at 37°C, we chose a previously established reaction condition for association and repletion (4°C)[31], and one that would slow cartilage metabolism, minimizing changes in PRG4 concentration due to biosynthesis, and allow for analysis of PRG4 binding.

The amount of PRG4-CHO or PRG4-OG-CHO which bound to articular cartilage surfaces in our experiments is similar to previously reported values where repletion of cartilage surfaces was conducted by incubation in synovial fluid [31]. Our results suggest that PRG4 (chemically functionalized or unmodified) can bind to the cartilage surface in absence of other synovial fluid constituents such as hyaluronic acid, although in vivo such molecules may still play an important role in facilitating PRG4 binding from synovial fluid. In addition, radiolabeled lubricin injected into the synovial joints of rats has been localized in cartilage, meniscus, and synovium tissues [27]. In clinical application, it is possible that injected PRG4 or PRG4-CHO would adhere to the surfaces of the aforementioned relevant tissues, and potentially increase therapeutic effect.

These findings are the first to exploit chemical functionalization to significantly enhance binding of PRG4 to cartilage surfaces. The increase in chemically modified PRG4 concentration at the cartilage surface suggests a possible therapeutic benefit of locally immobilizing lubricating molecules at the cartilage surface. Follow-up studies will be necessary to determine the durability and maintenance of PRG4-CHO at the cartilage surface as well as assess the impact of chemically immobilized PRG4 on the tribological properties of treated articular cartilage surfaces. Ultimately, it will be informative to translate these studies to the in vivo environment. Application of functionalized PRG4 to cartilage surfaces altered by early OA may delay further progression of the disease and provide a convenient method for overcoming loss of lubrication and associated articulation. Extracellular matrix molecules capable of reacting with CHO functionalized biomolecules are ubiquitous in all tissues; thus the concept of molecular resurfacing with functionalized biolubricants can likely be applied to other tissues such as meniscus and tendon. Finally, we note that lubricity is also a desirable surface property for a number of biomedical devices such as catheters, endoscopes and implants used in total hip or knee replacements[38]. In the future, we envision variations of the molecular resurfacing strategy described here being applied to biolubrication of synthetic materials, providing an alternative to existing approaches for enhancing functional lubrication of medical devices [39] [40].

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Izolda Popova, of the Monoclonal Antibody Core at Northwestern University and the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, for assistance with antibody generation. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Marsha Ritter-Jones and Dr. Hyung-Do Kim for helpful advice and discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 DE013030 and R01 EB005772).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schinagl RM, Gurskis D, Chen AC, Sah RL. Depth-dependent confined compression modulus of full-thickness bovine articular cartilage. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:499. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumacher BL, Su J-L, Lindley KM, Kuettner KE, Cole AA. Horizontally oriented clusters of multiple chondrons in the superficial zone of ankle, but not knee articular cartilage. Anat Rec. 2002;266:241. doi: 10.1002/ar.10063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jadin KD, Wong BL, Bae WC, Li KW, Williamson AK, Schumacher BL, Price JH, Sah RL. Depth-varying density and organization of chondrocyte in immature and mature bovine articular cartilage assessed by 3-D imaging and analysis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:1109. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6511.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckwalter JA, Mankin HJ. Articular cartilage. Part II: degeneration and osteoarthrosis, repair, regeneration, and transplantation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79-A:612. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mankin HJ. The response of articular cartilage to mechanical injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64-A:460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meachim G, Ghadially FN, Collins DH. Regressive changes in the superficial layer of human articular cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis. 1965;24:23. doi: 10.1136/ard.24.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikegawa S, Sano M, Koshizuka Y, Nakamura Y. Isolation, characterization and mapping of the mouse and human PRG4 (proteoglycan 4) genes. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;90:291. doi: 10.1159/000056791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schumacher BL, Hughes CE, Kuettner KE, Caterson B, Aydelotte MB. Immunodetection and partial cDNA sequence of the proteoglycan, superficial zone protein, synthesized by cells lining synovial joints. J Orthop Res. 1999;17:110. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schumacher BL, Block JA, Schmid TM, Aydelotte MB, Kuettner KE. A novel proteoglycan synthesized and secreted by chondrocytes of the superficial zone of articular cartilage. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:144. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher BL, Schmidt TA, Voegtline MS, Chen AC, Sah RL. Proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) synthesis and immunolocalization in bovine meniscus. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:562. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jay GD, Britt DE, Cha D-J. Lubricin is a product of megakaryocyte stimulating factor gene expression by human synovial fibroblasts. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swann DA, Silver FH, Slayter HS, Stafford W, Shore E. The molecular structure and lubricating activity of lubricin isolated from bovine and human synovial fluids. Biochem J. 1985;225:195. doi: 10.1042/bj2250195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jay GD, Tantravahi U, Britt DE, Barrach HJ, Cha CJ. Homology of lubricin and superficial zone protein (SZP): products of megakaryocyte stimulating factor (MSF) gene expression by human synovial fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes localized to chromosome 1q25. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:677. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanson SAV. Friction, Wear, and Lubrication. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult Articular Cartilage. Tunbridge Wells, England: Pitman Medical; 1979. p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcelino J, Carpten JD, Suwairi WM, Gutierrez OM, Schwartz S, Robbins C, Sood R, Makalowska I, Baxevanis A, Johnstone B, Laxer RM, Zemel L, Kim CA, Herd JK, Ihle J, Williams C, Johnson M, Raman V, Alonso LG, Brunoni D, Gerstein A, Papadopoulos N, Bahabri SA, Trent JM, Warman ML. CACP, encoding a secreted proteoglycan, is mutated in camptodactyly-arthropathy-coxa vara-pericarditis syndrome. Nat Genet. 1999;23:319. doi: 10.1038/15496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid TM, Su J-L, Lindley KM, Soloveychik V, Madsen L, Block JA, Kuettner KE, Schumacher BL. Superficial Zone Protein (SZP) is an Abundant Glycoprotein in Human Synovial Fluid with Lubricating Properties. In: Kuettner KE, Hascall VC, editors. The Many Faces of Osteoarthritis. New York: Raven Press; 2002. p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jay GD. Characterization of a bovine synovial fluid lubricating factor. I. Chemical, surface activity and lubricating properties. Connect Tissue Res. 1992;28:71. doi: 10.3109/03008209209014228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jay GD, Carpten JD, Rhee DK, Torres JR, Marcelino J, Warman ML. Analysis of the frictional characteristics of CACP knockout mice joints with the modified stanton pendulum technique. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 2003;28:136. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt TA, Gastelum NS, Nguyen QT, Schumacher BL, Sah RL. Boundary lubrication of articular cartilage: role of synovial fluid constituents. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:882. doi: 10.1002/art.22446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young A, McLennan S, Smith M, Smith S, Cake M, Read R, Melrose J, Sonnabend D, Flannery C, Little C. Proteoglycan 4 downregulation in a sheep meniscectomy model of early osteoarthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2006;8:R41. doi: 10.1186/ar1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elsaid KA, Jay GD, Chichester CO. Reduced expression and proteolytic susceptibility of lubricin/superficial zone protein may explain early elevation in the coefficient of friction in the joints of rats with antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;56:108. doi: 10.1002/art.22321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teeple E, Fleming BC, Jay GD, Aslani K, Crisco KK, Mechrefe AP. Coefficients of friction, lubricin, and cartilage damage in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient guinea pig knee. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2008;26:231. doi: 10.1002/jor.20492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsaid KA, Fleming BC, Oksendahl HL, Machan JT, Fadale PD, Hulstyn MJ, Shalvoy R, Jay GD. Decreased lubricin concentrations and markers of joint inflammation in the synovial fluid of patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2008;58:1707. doi: 10.1002/art.23495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt KD, Smith GNJ, Simon LS. Intraarticular injection of hyaluronan as treatment for knee osteoarthritis: what is the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1192. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200006)43:6<1192::AID-ANR2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strauss EJ, Hart JA, Miller MD, Altman RD, Rosen JE. Hyaluronic Acid Viscosupplementation and Osteoarthritis: Current Uses and Future Directions. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0363546508326984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones ARC, Gleghorn JP, Hughes CE, Fitz LJ, Zollner R, Wainwright SD, Caterson B, Morris EA, Bonassar LJ, Flannery CR. Binding and localization of recombinant lubricin to articular cartilage surfaces. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2007;25:283. doi: 10.1002/jor.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flannery CR, Zollner R, Corcoran C, Jones AR, Root A, Rivera-Bermúdez MA, Blanchet T, Gleghorn JP, Bonassar LJ, Bendele AM, Morris EA, Glasson SS. Prevention of cartilage degeneration in a rat model of osteoarthritis by intraarticular treatment with recombinant lubricin. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;60:840. doi: 10.1002/art.24304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang DA, Varghese S, Sharma B, Strehin I, Fermanian S, Gorham J, Fairbrother DH, Cascio B, Elisseeff JH. Multifunctional chondroitin sulphate for cartilage tissue-biomaterial integration. Nat Mater. 2007;6:385. doi: 10.1038/nmat1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes JMG, Herretes S, Pirouzmanesh A, Wang D-A, Elisseeff JH, Jun A, McDonnell PJ, Chuck RS, Behrens A. A modified chondroitin sulfate aldehyde adhesive for sealing corneal incisions. Invest Ophthal & Visual Sci. 2005;46:1247. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt TA, Schumacher BL, Klein TJ, Voegtline MS, Sah RL. Synthesis of proteoglycan 4 by chondrocyte subpopulations in cartilage explants, monolayer cultures, and resurfaced cartilage cultures. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2849. doi: 10.1002/art.20480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nugent-Derfus GE, Chan AH, Schumacher BL, Sah RL. PRG4 exchange between articular cartilage surface and synovial fluid. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:1269. doi: 10.1002/jor.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate Techniques. New York: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraehenbuhl JP, Galardy RE, Jamieson JD. Preparation and Characterization of an Immuno-Electron Microscope Tracer Consisting of a Heme-Octapeptide Couple to Fab. J Exp Med. 1973;139:208. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galardy RE, Stafford SS, Schaefer ML, Ho H, LaVorgna KA, Jamieson JD. Biologically Active Derivatives of Angiotensin for Labeling Cellular Receptors. J Med Chem. 1978;21:1279. doi: 10.1021/jm00210a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baynes JW, Monnler VM, editors. The Maillard Reaction in Aging, Diabetes, and Nutrition. Alan R. Liss, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt TA, Plaas AJK, Sandy JA. Disulfide-bonded multimers of proteoglycan 4 (PRG4) are present in normal synovial fluids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauffenburger DA, Linderman JJ. Receptors: Models for Binding, Trafficking, and Signaling. New York, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikada Y. Lubricating polymer surfaces. Technomic Publishing Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S, Spencer ND. Poly(L-lysine)-graft-Poly(ethylene glycol) (PLL-g-PEG): A universal aqueous lubricant additive for tribosystems involving thermoplastics. Lubrication Science. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chawla K, Lee S, Lee BP, Dalsin JL, Messersmith PB, Spencer ND. A Novel Low Friction Surface for Biomedical Applications: Modification of Poly(dimethylsiloxane) with Poly(ethylene glycol)-DOPA-Lysine. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;90A:742. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]