Abstract

An ability to quantitate the beta cell mass by noninvasive nuclear imaging will be very useful in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diabetes. However, to be successful, radioactivity from the pancreas must not be obscured by the background radioactivity in the abdomen. Pretargeting offers the promise of achieving high target organ to normal tissue ratios. In preparation for pancreas imaging studies by pretargeting using morpholino oligomers (MORF/cMORF), it was necessary to develop a simple and efficient method to radiolabel the cMORF effector. Because we have shown that labeling the cMORF with 111In via DTPA reduces excretion into the intestines compared to labeling with 99mTc via MAG3, the conjugation of DTPA to cMORF were investigated for the 111In labeling. The amine-derivatized cMORF was conjugated with DTPA using EDC (1-Ethyl-3(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride) as an alternative to the conventional cyclic anhydride. The conjugation efficiency (represented by the number of DTPA groups attached per cMORF) was investigated by changing the EDC, DTPA and cMORF molar ratios. Different open columns were considered for the purification of DTPA-cMORF. Before conjugation, each cMORF molecule was confirmed to have an amine by trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) assay using the ω-amino butyric acid as positive standrad and the non-amine derivatized cMORF as negative standard. The average number of DTPA groups per cMORF was 0.15–0.20 following the conjugation with DTPA over a cMORF/DTPA molar ratio of 0.5 to 5 and over a cMORF/EDC molar ratio of 20 to 60. The conjugation efficiency was lower than expected probably due to steric hindrance. A 1×50 cm P-4 column using ammonia acetate as eluting buffer provided an adequate separation of DTPA-cMORF from free DTPA. The 111In labeling efficiency by transchelation from acetate exceeded 95%, thus avoiding the need for postlabeling purification. Despite the lower than expected conjugation efficiency in which no more than one-fifth of the cMORF were DTPA-derivatized, a specific radioactivity of at least 300 µCi/µg or 1.90 Ci/µmol of cMORF was achieved. In conclusion, a protocol is described for 111In-DTPA-cMORF that provides the high specific activity favorable to beta cell imaging because of the low mass fraction of beta cells in pancreas (1–2%) and obviates the need for postlabeling purification.

Keywords: DNA analog, conjugation, purification, radiolabeling, Indium-111

INTRODUCTION

Insulin is secreted by the beta cells in the islets of Langerhans that are scattered throughout pancreas. By the time hyperglycemia appears in animals or in humans, up to 90% of beta cell mass has been destroyed (Gepts et al., 1981; Saito et al., 1979; Bonner-Weir et al., 1983; Tominaga et al., 1986; Polonsky et al., 1996). An ability to quantitate the beta cell mass in the pancreas by any noninvasive means will be invaluable to the diagnosis of diabetes, the monitoring of its progression, and the function evaluation of transplanted islets (Souza et al., 2006). Since the islets of Langerhans consitute only about 1–2% of the pancreas mass (Souza et al., 2006), only those extremely sensitive modalities, such as nuclear imaging, hold promise of success. In addition, as shown by previous attempts to image the pancreas by targeting beta cells (Goland et al., 2009; Kung et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2006; Korner et al., 2007; Wild et al., 2006; Kwan et al., 2005; Moore et al., 2001; Saudek et al. 2008), accumulation of the radiolabel in the normal organs forming the pathways of excretion in the proximity of the pancreas can severely compromise the detection. In addition, the approaches currently under consideration each have its own disadvantages. One imaging approach targets the vesicular monoamine transporter-type 2 (VMAT2), but the accumulation of the VMAT2 targeting agents is not pancreas specific (Goland et al., 2009; Kung et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2006). Another approach targets the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor, but the accumulation of GLP-1 targeting agents strongly depend on the glucose level in blood (Korner et al., 2007; Wild et al., 2006; Kwan et al., 2005). Efforts have also been made to target islet cells with radiolabeled antibodies (Moore et al., 2001; Saudek et al. 2008), but the slow clearance that characterizes intact radiolabeled antibodies is problematic. We believe that pretargeting may offer a useful alternative to these and other approaches since pretargeting approach using radiolabeled effector combines the high detection sensitivity characteristic of nuclear imaging with improved target/nontarget ratios (Karacay et al., 2005; Sharkey et al 2005; Pagel et al., 2003; Subbiah et al., 2003; Magnani et al., 1996).

To our knowledge, pretargeting has not yet been considered for targeting diseases other than cancers. This laboratory is developing a pretargeting approach in which a phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (MORF) is conjugated to the targeting antibody while its complement (cMORF) is radiolabeled and administered after the antibody has cleared from normal organs (Liu et al., 2008). In previous studies in mouse models, the radiolabel for the cMORF is usually 99mTc. Although the 99mTc-cMORF clears from the circulation into the bladder rapidly, about 2% accumulates into the intestines. This small percent of hepatobilliary clearance can interfere with pancreas imaging especially since the radioactivity is subject to movement. Fortunately, we have shown that replacing 99mTc with 111In using DTPA as the chelator eliminates this abdominal accumulation (Liu et al., 2009).

Labeling with 111In usually involves either diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA) or 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclodecance-N,N’,N”,N’’’-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) with different linkers (Brechbiel 2009; Liu 2008). Although we have used the commercially available p-SCN-Bz- DOTA to label a 25 mer MORF with 90Y and 111In (Liu et al., 2003), the labeling method used then is now considered unsatisfactory because of the need for postlabeling purification and because of slight instabilities of the 111In in serum (data not presented). Since we also experienced instability with the commercially available p-SCN-Bz-DTPA, we selected DTPA along with 1-Ethyl- 3(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (Yamada et al., 1981) as an alternative, despite the loss of one carboxylate group in the conjugation to cMORF (Brechbiel et al., 1986; Brockmann et al., 1999). The carbodiimide coupling of DTPA to cMORF was used alternative to the cyclic DTPA anhydride (Hnatowich et al., 1983; Zhang et al., 1983) because of its versatility for conjugating carboxylates to amine derivatized biologicals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The MORF and cMORF with the base sequences of 5′-TCT TCT ACT TCA CAA CTA and 5′-TAG TTG TGA AGT AGA AGA respectively were obtained from Gene-Tools (Philomath, OR) both with and without the 3’amine. The 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS or picrylsulfonic acid), ω-amino butyric acid, and DTPA were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The EDC (1-Ethyl-3(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride) was from Pierce Company (Rockford, IL). The P-4 resin (Bio-Gel P-4 Gel, medium) was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). The G25 was recovered from a commercial PD-10 column (Neorex Corp, Seattle, WA). The 111InCl3 was from Perkin Elmer Life Science Inc (Boston, MA). All other chemicals were reagent grade and used without purification.

The MORF concentrations were quantitated by UV spectrophotometer (U-2000, Hitachi Instruments Inc., Danbury, CT) using the molar absorbance values provided by Gene-Tools. Size exclusion HPLC was used to analyze the conjugation mixtures and the fractions from open columns and to monitor the stability of modified cMORFs in different media. The Superdex™ 75 column (optimal separation range: 1×102 to 7×103 Da; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) was eluted with 0.10 M pH 7.2 phosphate buffer at a flow rate of 0.60 mL/min. An in-line radioactive detector and an in-line Waters 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector were used. Recovery was routinely measured in the analysis of all radiolabeled samples using a dose calibrator.

Measuring the amines on cMORF

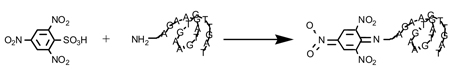

The presence of amines on the commercial cMORF was confirmed by the TNBS analysis illustrated below (Satake et al., 1960): A curl has been used to represent the cMORF to suggest that the chain may not be linear in solution.

Along with the amine derivatized cMORF, an ω-amino butyric acid and the non-amine derivatized cMORF (native cMORF) were used as positive and negative standards respectively. Specifically, 0-60 µL of NH2-cMORF (0.125 mM), NH2(CH2)3COOH (0.200 mM), or cMORF (0.083 mM) was mixed with 50 µL 4% NaHCO3 and 50 µL of 0.02% TNBS and finally diluted with H2O to 160 µL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h and then combined with 25 µL of 1 N HCl and 15 µL of 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate before measuring the OD values at 335 nm. The OD values for each reagent were plotted against its concentration and the curve was fitted linearly. The average numbers of amines per cMORF was calculated by (Slope NH2-cMORF-Slope cMORF)/Slope NH2(CH2)3COOH.

Conjugation of DTPA to NH2-cMORF

The conjugation of DTPA to NH2-cMORF in the presence of EDC is illustrated below:

The conjugation was achieved in 0.1 M MES (pH 5.0) by mixing a solution of DTPA (1 µg/µL) with an EDC solution (4 µg/µL) and then with a NH2-cMORF solution (3 µg/µL). The influences of conjugation time and molar ratios of EDC and DTPA to NH2-cMORF on the conjugation efficiency (defined by the average number of DTPA groups per molecule of cMORF, gpm) were examined. The gpm was measured by labeling the conjugation mixture before purification with 111In acetate followed by SE HPLC analysis assuming that free and conjugated DTPAs have the same affinity for indium (Hnatowich et al., 1982).

Column purification of DTPA-cMORF

Three open columns (1.5 × 8, 0.7 × 20 and 1 × 50 cm) each with two different solid resins (P-4 or G25) were evaluated with 0.25 M ammonium acetate (pH 5.2) and 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) as eluant for the purification. In each case an aliquot of the conjugated mixture, after radiolabeling by the addition of 111In acetate, was loaded onto the column and fractions were collected and counted in a NaI(Tl) well counter (Cobra II automatic gamma counter, Packard Instrument Company, CT). In this manner, combinations of columns and elution buffers were tested under the assumption that the unlabeled and the radiolabeled forms of DTPA-MORF and DTPA have the same elution profiles. Fractions were collected as before with each fraction measured at 265 nm for its OD value and an aliquot of each fraction was also radiolabeled simply by adding the 111In acetate and analyzed by HPLC. Eventually the combination of P-4, the ammonium acetate buffer, and 1 × 50cm column was selected for the purification of DTPA-cMORF. Peak fractions were combined as a stock solution.

Stability of DTPA-cMORF

Stability of the unlabeled DTPA-cMORF was examined in the ammonium acetate buffer by removing aliquots periodically for radiolabeling, while the stability of the radiolabel in mouse serum was measured by incubating 10–20 µL (about 0.2 µg/µL) of labeled cMORF in 250 µL mouse serum at 37 °C followed by HPLC analysis. The integrity of cMORF after conjugation and labeling was also examined by HPLC before and after the addition of MORF in excess.

RESULTS

Measuring the amines on cMORF

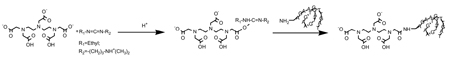

Fig 1 presents the OD values at 335 nm versus the concentrations for NH2-cMORF, ω-amino butyric acid, and native cMORF after incubation with TNBS. Although it was reported that guanine moieties may react with TNBS (Azegami et al., 1964), only a slight absorbance was observed for the native cMORF (six guanines per molecule), suggesting that either the base moieties do not react with TNBS under our experimental conditions or the trinitrophenylized cMORFs do not absorb at this wavelength. By contrast, the absorbance of NH2-cMORF exceeded that of the positive standard ω-amino butyric acid. However, after correcting for the contribution of the native cMORF, the absorbance of TNB=N-cMORF (slope 0.0105) was identical within experimental error to that of TNB=N-(CH2)3COOH (slope 0.0107), resulting in a value of 0.98 for the average number of amines per cMORF and suggesting almost each cMORF bears an amine as it theoretically should be.

Fig 1.

The OD values at different concentrations of the reaction products of TNBS with NH2- cMORF (solid circles), ω-amino butyric acid (open circles) and native cMORF (triangles). The error bars represent one standard deviation.

Conjugation of DTPA to cMORF

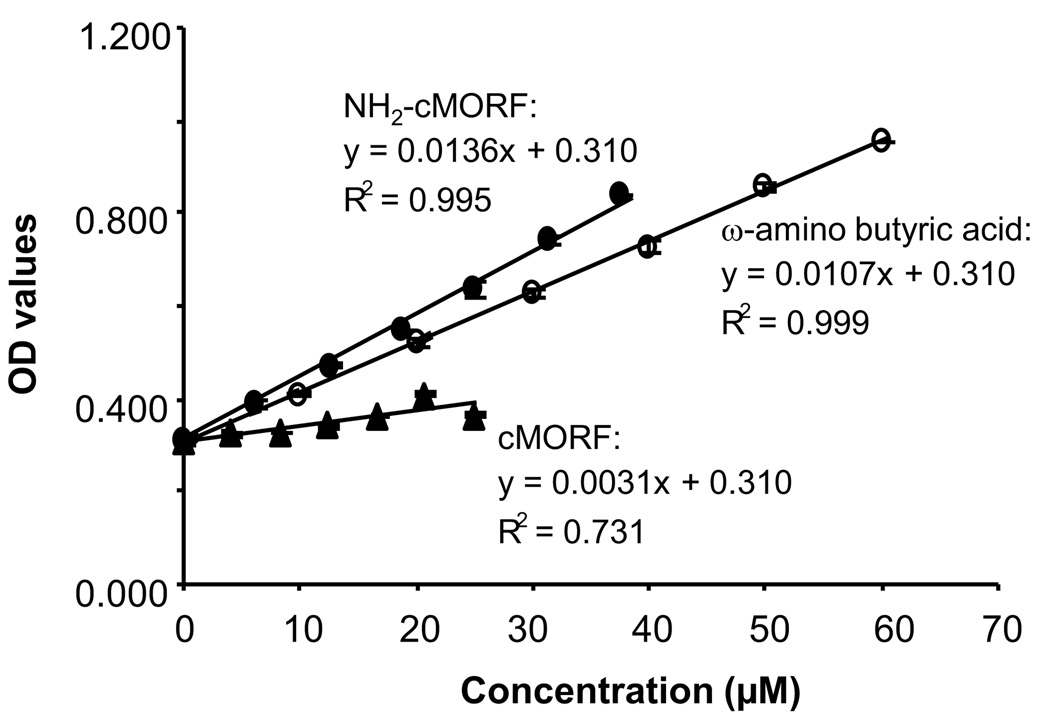

The conjugation efficiency (represented by the average gpm of DTPA on cMORF) was neither improved by waiting more than 5 min prior to the addition of NH2-cMORF after mixing EDC and DTPA nor by waiting more than 1 h thereafter (data not presented). Also, no major increase in conjugation efficiency was observed by increasing the EDC molar ratios between 1:(20–60):1 (DTPA:EDC:NH2-cMORF), which is as expected since EDC was always present in large excess. However, it was surprising that an increase in conjugation efficiency was not observed by increasing the DTPA molar ratio between (0.5–5):45:1 as shown in Fig 2, since the DTPA was not in great excess. The average gpm of DTPA never exceeded 0.20 and increasing the molar ratio of DTPA to cMORF actually lowered the gpm. Since the lower than expected gpm was not due to insufficient DTPA, it may be due to spatial hindrance of the activated EDC-DTPA ester to the amine on the cMORF.

Fig 2.

The conjugation efficiency (represented by gpm, the number of DTPA groups per cMORF molecule) vs. increasing DTPA/cMORF molar ratio in the range of DTPA:EDC: NH2- cMORF of (0.5–5):45:1.

Column purification of DTPA-cMORF

Although the separation of free DTPA from DTPA-cMORF was largely independent of the choice of eluant on both P-4 or G25, the 0.25 M ammonium acetate (pH 5.2) buffer was selected to avoid aggregate formation in phosphate buffer. If the phosphate buffer was used as open column eluting-buffer, in the subsequent HPLC analysis the recovery of the conjugate was poor and repetitive injections increased the HPLC system pressure. The P-4 gel was selected over G25 for the subsequent studies simply for convenience.

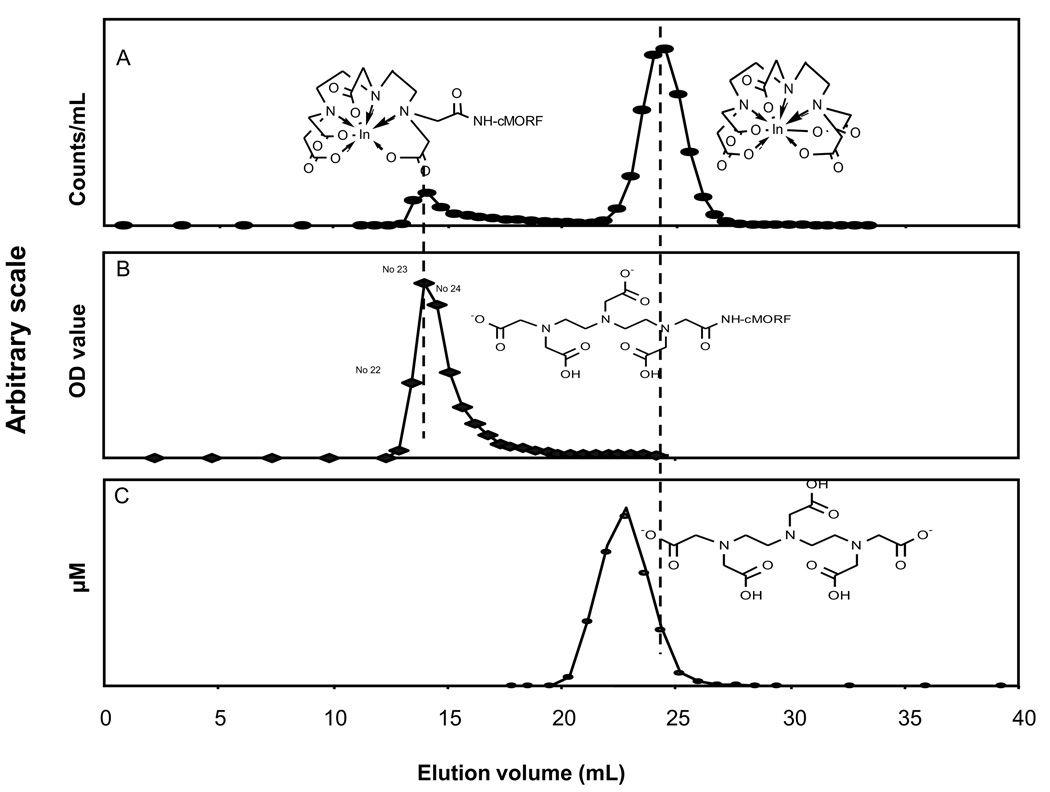

The elution profile of a 111In labeled conjugation mixture (conjugation molar ratio DTPA/EDC/cMORF 1/45/1) on the 1×50 cm P-4 column using the ammonium acetate buffer is presented in Fig 3 (panel A). As shown, the 111In labeled cMORF and the 111In labeled DTPA are well separated under these conditions. Also presented in the figure is the UV profile at 265 nm of the unlabeled mixture (panel B), only showing the elution profile of DTPA-cMORF since DTPA does not absorb at this wavelength. The retention time of DTPA-cMORF is clearly unchanged after labeling. The elution profile of unlabeled DTPA (panel C) under these conditions was obtained by adding a known amount of DTPA-cMORF to each fraction containing only DTPA and labeling each with 111In. By assuming that free and conjugated DTPA have the same affinity for indium (Hnatowich et al., 1982), the DTPA concentrations was calculated for each fraction from the areas of the two 111In peaks. As shown, free DTPA (panel C) elutes earlier than 111In- DTPA (panel A) but under these conditions the separation of free DTPA from DTPA-cMORF is satisfactory. However, using either of the two shorter columns (1.5 × 8 and 0.7 × 20 cm), elution of the free DTPA overlapped sufficiently with that of the DTPA-cMORF such that an adequate separation was not possible (data not presented), although separation between labeled DTPA-and labeled DTPA-cMORF seems satisfactory.

Fig 3.

Elution profiles obtained on the 1×50 cm P-4 column with 0.25M ammonium acetate eluant of the radiolabeled conjugation mixture by radioactivity detection (panel A) and the unlabeled conjugation mixture by UV detection at 265 nm (panel B). Also presented is the elution profile of unlabeled DTPA (panel C).

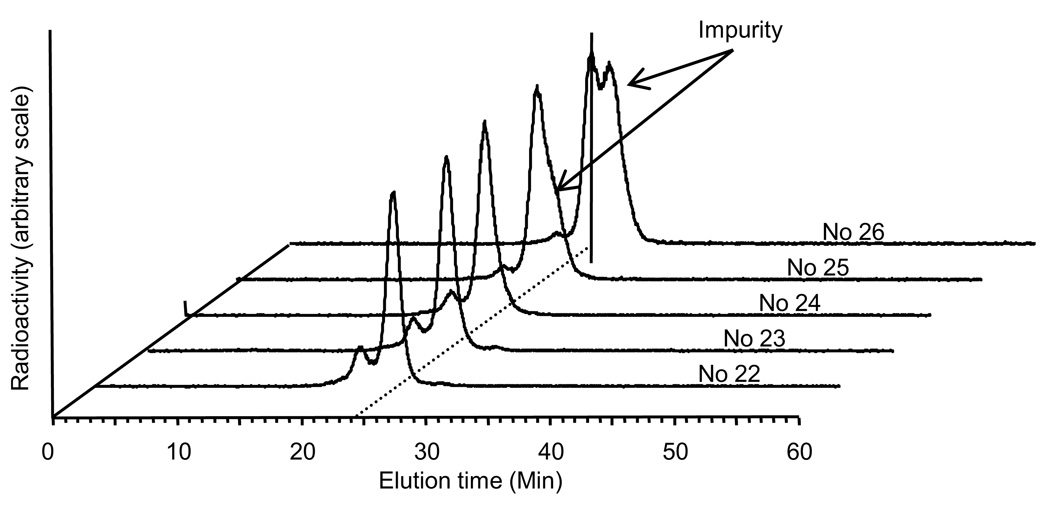

Fig 4 presents HPLC radiochromatograms of five peak fractions of a conjugation mixture (conjugation molar ratio DTPA/EDC/cMORF of 1/45/1) off the 1 × 50 cm P-4 column, after each fraction was radiolabeled with 111In. The labeled DTPA eluting at 28.5 min is absent in all the five fractions. However, an unidentified impurity peak appears in fraction 25 and 26. Before the main peak at 24.5 min, another small peak at 21.5 min is present in the early fractions but it is not due to an impurity since the species responsible for this peak may be converted into the DTPA-cMORF by slight heating (data not presented). Fractions 22 to 24 were pooled and aliquots were radiolabeled with the labeling efficiency exceeding 95%.

Fig 4.

Radiochromatographic profiles by HPLC analysis of five fractions off the P-4 column after 111In labeling. The Superdex™ 75 column was eluted with a 0.10 M pH 7.2 phosphate buffer at a flow rate of 0.60 mL/min.

Stability and integrity of the labeled cMORF

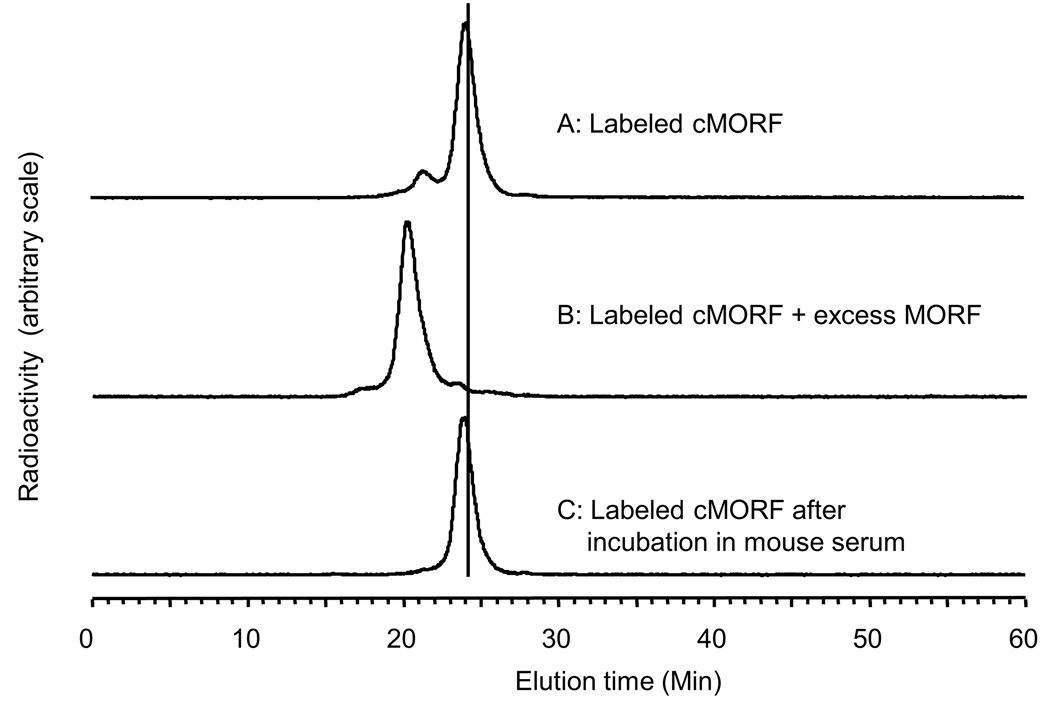

The purified DTPA-cMORF was found to be stable in the ammonium acetate buffer at room temperature for at least 3 days and has now been stored in that buffer at freezer temperatures for over a year with no sign of instability. Figure 5 presents a typical HPLC radiochromatgram of radiolabeled DTPA-cMORF (panel A). The radiolabeled cMORF can be completely shifted to higher molecular weight following the addition of MORF in excess (panel B). Incubation of the radiolabeled DTPA-cMORF in 37 °C mouse serum showed no evidence of dissociation over 6 hours (panel C). The only small difference in the radioactivity profiles of the labeled cMORF between buffer and serum is that the small peak at 21.5 min seen in buffer (panel A) disappears in serum (panel C). By HPLC with UV detection, the NH2-cMORF and native cMORF also show this small peak. It also disappears upon heating and binding to MORF (data not presented). Therefore, the peak is probably the result of intermolecular self-association in equilibrium with the main peak in labeling buffer at room temperature.

Fig 5.

Radiochromatographic profiles by HPLC analysis of labeled DTPA-cMORF before (panel A), and after the addition of excess MORF (panel B) and after incubation at 37 °C up to 6 h in mouse serum (panel C). The Superdex™ 75 column was eluted with a 0.10 M pH 7.2 phosphate buffer at a flow rate of 0.60 mL/min.

DISCUSSION

Even though pretargeting can provide much lower background radioactivity levels compared to conventional immunoscintigrapy, the target/nontarget ratio does depend in part upon the nature of the effector. For example, we have shown that cMORF effectors when radiolabeled with 99mTc via MAG3 show reduced retention of radioactivity in the kidneys with decreasing cytosines residues (Liu et al., 2002a). While the levels of normal tissue accumulations achieved with our selected cMORF sequence (shown in the material section) may be acceptable for most pretargeting applications, pancreas imaging by beta cell pretargeting will require extraordinarily low radioactivity levels of normal tissue accumulations especially in the intestines. Using the same cMORF sequence, we have shown that labeling with 111In via DTPA provides much lower intestinal radioactivity compared to the 99mTc-labeled cMORF via MAG3 (Liu et al., 2009). This investigation was performed to optimize the conjugation and purification of DTPA-cMORF for the 111In labeling.

Prior to conjugation, the presence of an amine on each of the commercial amine-derivatized cMORF was confirmed. The influence of EDC and DTPA molar ratios on the DTPA groups attached (gpm) was then evaluated. Thereafter, different column materials and dimensions and different eluants were evaluated for purification of the DTPA-cMORF from free DTPA. Eventually a 1 × 50 cm P-4 column using 0.25 M ammonia acetate buffer was selected. The conjugated cMORF could be stored for prolonged periods without degradation and radiolabeling provides consistently a radiochemical purity of greater than 95%, obviating the need for a postlabeling purification.

In previous studies with amine-derivatized cMORF (Liu et al, 2003; Liu et al. 2002b; 2006; Wang et al., 2006), the presence of the amine was not in doubt and not confirmed. However, after the conjugation efficiency of DTPA to cMORF was found to be about 20%, measuring the amine group on each cMORF became necessary. Using a TNBS assay, we were able to confirm that the low conjugation efficiency was not due to an incomplete amine derivatization of cMORF. One possible explanation for the lower than expected conjugation efficiency is steric hindrance. Due to interaction between base residues, the MORF oligomer in the pH 5 MES solution may be assuming a folded configuration such that the primary amine may not be exposed in all of the configurations and therefore less available for conjugation. However, that the 0.98 amine groups per cMORF obtained is close to the theoretical value of 1 indicates the spatial hindrance of amine on cMORF for TNBS is not so serious. The unrestricted accessibility for the TNBS maybe explained if the higher pH condition of 8–9 have opened the folded cMORF structure.

Despite a lower than expected conjugation efficiency (only about 20% of the amines on cMORF were conjugated with DTPA), the conjugation product was still radiolabeled at a specific radioactivity as high as 300 µCi/µg (1.90 Ci/µmol). At this specific activity, about 4 % of the total cMORF molecules and about 25% of the DTPA-cMORF molecules are associated with 111In.

CONCLUSION

A conjugation protocol has been developed for radiolabeling DTPA-cMORF with 111In that provides a labeling efficiency of at least 90 % and therefore may be suitable for kit formulation. In addition, the high specific activity reached (at least 300 µCi/µg) should be favorable to the beta cell imaging by pretargeting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Financial supports are from Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International (JDRF 37- 2009-7) and National Institutes of Health (CA94994 and CA107360).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Azegami M, Iwai K. Specific modification of nucleic acids and their constituents with trinitrophneyl group. J Biochem. 1964;55:346–348. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a127892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner-Weir S, Trent DF, Weir GC. Partial pancreatectomy in the rat and subsequent defect in glucoseinduced insulin release. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:1544–1553. doi: 10.1172/JCI110910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechbiel MW. Bifunctional chelates for metal nuclides. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:166–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechbiel MW, Gansow OA, Atcher RW, Schlom J, Esteban J, Simpson D, Colcher D. Synthesis of 1-(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl) derivatives of DTPA and EDTA. Antibody labeling and tumor-imaging studies. 1986;25:2772–2781. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann J, Rosch F. Determination of stability constants in Y-DTPA-peptide-systems: Evaluation of a radiochemical method using n. c. a. Yttrium-88. Radiochim Acta. 1999;87:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts W, Lecompte PM. The pancreatic islets in diabetes. Am J Med. 1981;70:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goland R, Freeby M, Parsey R, Saisho Y, Kumar D, Simpson N, Hirsch J, Prince M, Maffei A, Mann JJ, Butler PC, Van Heertum R, Leibel RL, Ichise M, Harris PE. 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine PET of the pancreas in subjects with long-standing type 1 diabetes and in healthy controls. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:382–389. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnatowich DJ, Layne WW, Childs RL. The preparation and labeling of DTPA-coupled albumin. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1982;33:327–332. doi: 10.1016/0020-708x(82)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnatowich DJ, Layne WW, Childs RL, Lanteigne D, Davis MA, Griffin TW, Doherty PW. Radioactive labeling of antibody: a simple and efficient method. Science. 1983;220(4597):613–615. doi: 10.1126/science.6836304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karacay H, Brard PY, Sharkey RM, et al. Therapeutic advantage of pretargeted radioimmunotherapy using a recombinant bispecific antibody in a human colon cancer xenograft. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7879–7885. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner M, Stöckli M, Waser B, Reubi JC. GLP-1 receptor expression in human tumors and human normal tissues: potential for in vivo targeting. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:736–743. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.038679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung MP, Hou C, Lieberman BP, Oya S, Ponde DE, Blankemeyer E, Skovronsky D, Kilbourn MR, Kung HF. In vivo imaging of beta-cell mass in rats using 18F-FP- (+)-DTBZ: a potential PET ligand for studying diabetes mellitus. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1171–1176. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan EP, Gaisano HY. Glucagon-like peptide 1 regulates sequential and compound exocytosis in pancreatic islet beta-cells. Diabetes. 2005;54:2734–2743. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CB, Liu GZ, Liu N, Zhang YM, He J, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Radiolabeling morpholinos with 90Y, 111In, 188Re and 99mTc. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, He J, Zhang S, Liu C, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Cytosine residues influence kidney accumulations of 99mTc-labeled morpholino oligomers. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2002a;12:393–398. doi: 10.1089/108729002321082465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Zhang S, He J, et al. Improving the labeling of S-acetyl NHS-MAG3- conjugated morpholino oligomers. Bioconjug. Chem. 2002b;13:893–897. doi: 10.1021/bc0255384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Dou S, He J, et al. R adiolabeling of MAG3-morpholino oligomers with 188Re at high labeling efficiency and specific radioactivity. Appl Radiat Isot. 2006;64:971–978. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Hnatowich DJ. A semiempirical model of tumor pretargeting. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:2095–2104. doi: 10.1021/bc8002748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Cheng D, Dou S, Chen X, Liang M, Pretorius PH, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Replacing 99mTc with 111In improves MORF/cMORF pretargeting by reducing intestinal accumulation. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11:303–307. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0209-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. Bifunctional coupling agents for radiolabeling of biomolecules and target-specific delivery of metallic radionuclides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1347–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Dang H, Middleton B, Zhang Z, Washburn L, Stout DB, Campbell-Thompson M, Atkinson MA, Phelps M, Gambhir SS, Tian J, Kaufman DL. Noninvasive imaging of islet grafts using positron-emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11294–11299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603909103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani P, Paganelli G, Modorati G, et al. Quantitative comparison of direct antibody labeling and tumor pretargeting in uveal melanoma. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:967–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Bonner-Weir S, Weissleder R. Noninvasive in vivo measurement of beta-cell mass in mouse model of diabetes. Diabetes. 2001;50:2231–2236. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel JM, Hedin N, Subbiah K, et al. Comparison of anti-CD20 and anti-CD45 antibodies for conventional and pretargeted radioimmunotherapy of B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2003;101:2340–2348. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky KS, Sturis J, Bell GI. Seminars in Medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Non-insulindependent diabetes mellitus - a genetically programmed failure of the beta cell to compensate for insulin resistance. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:777–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake K, Okuyama T, Ohashi M, Shinoda T. The spectrophotometric determination of amine, amino acid and peptide with 2,4,6-tronitrobenzene 1-sulfonic acid. J Biochem. 1960;47:654–660. [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Yaginuma N, Takahashi T. Differential volumetry of A, B and D cells in the pancreatic islets of diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Tohoku. J Exp Med. 1979;129:273–283. doi: 10.1620/tjem.129.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudek F, Brogren CH, Manohar S. Imaging the Beta-cell mass: why and how. Rev Diabet Stud. 2008;5:6–12. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2008.5.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey RM, Cardillo TM, Rossi EA, et al. Signal amplification in molecular imaging by pretargeting a multivalent, bispecific antibody. Nat Med. 2005;11:1250–1255. doi: 10.1038/nm1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza F, Freeby M, Hultman K, et al. Current progress in non-invasive imaging of beta cell mass of the endocrine pancreas. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:2761–2773. doi: 10.2174/092986706778521940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiah K, Hamlin DK, Pagel JM, et al. Comparison of immunoscintigraphy, efficacy, and toxicity of conventional and pretargeted radioimmunotherapy in CD20- expressing human lymphoma xenografts. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Maruyama H, Bolli G, et al. Simulation of the normal glucopenia-induced decline in insulin partially restores the glucagon response to glucopenia in isolated perfused pancreata of streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Endocrinology. 1986;118:886–887. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-2-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu G, Hnatowich DJ. Methods for MAG3 conjugation and 99mTc radiolabeling of biomolecules. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1477–1480. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild D, Béhé M, Wicki A, Storch D, Waser B, Gotthardt M, Keil B, Christofori G, Reubi JC, Mäcke HR. [Lys40(Ahx-DTPA-111In)NH2]exendin-4, a very promising ligand for glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor targeting. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:2025–2033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Imoto T, Fujita K, Okazaki K, Motomura M. Selective modification of aspartic acid-101 in lysozyme by carbodiimide reaction. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4836–4842. doi: 10.1021/bi00520a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YM, Liu N, Zhu ZH, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Influence of different chelators (HYNIC, MAG3 and DTPA) on tumor cell accumulation and mouse biodistribution of technetium-99m labeled to antisense DNA. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:1700–1707. doi: 10.1007/s002590000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]