Abstract

The goal of this work was to develop and validate a whole bone organ culture model to be utilized in biomimetic mechanotransduction research. Femurs harvested from 2-day-old neonatal rat pups were maintained in culture for 1 week post-harvest and assessed for growth and viability. For stimulation studies, femurs were physiologically stimulated for 350 cycles 24 h post-harvest then maintained in culture for 1 week at which time structural tests were conducted. Comparing 1 and 8 days in culture, bones grew significantly in size over the 7-day culture period. In addition, histology supported adequate diffusion and organ viability at 2 weeks in culture. For stimulation studies, 350 cycles of physiologic loading 24 h post-harvest resulted in increased bone strength over the 7-day culture period. In this work, structural proof of concept was established for the use of whole bone organ cultures as mechanotransduction models. Specifically, this work established that these cultures grow and remain viable in culture, are adequately nourished via diffusion and are capable of responding to a brief bout of mechanical stimulation with an increase in strength.

Keywords: Mechanotransduction, Organ culture, Rat femur, Biomimetic, Biomechanics

1 Introduction

Mechanotransduction models are utilized in bone research to investigate the mechanisms by which bone cells perceive and respond to a mechanical stimulus. Depending upon the research question asked and the goal of the study, mechanotransduction research is most commonly pursued using in vitro (cellular) or in vivo (loading/unloading) models. While much has been learned about the response of bone cells to stimulation from in vitro cell models, these systems have several drawbacks including the utilization of cells in monolayer, dissociation of the cells from the extracellular matrix and the inability to correctly preserve the three-dimensional (3D) architecture of the communication networks found in living bone. While these drawbacks serve as arguments for the use of in vivo models, these systems also present complications. For example, normal loading of the bone can desensitize it to experimental stimulation. Rubin and Lanyon overcame this issue by using an isolated turkey ulna whose mechanical loading could be tightly controlled throughout experimentation (Rubin and Lanyon 1984, 1985). However, this model did not lend itself well to molecular studies. Currently, rodent models are commonly utilized given the availability of antibodies and transgenics (Turner et al. 1991; Hillam and Skerry 1995). Using an ex vivo or organ culture modeling approach, whole bone maintained in culture may be subjected to stimulation and the effect of the stimulation assessed in a physiologic milieu maintaining appropriate cell types and numbers within their 3D, communication-intact environment. Thus, we believe that the organ culture models are more ‘biomimetic’ than in vitro models and as such have tremendous potential in mechanotransduction research aimed at dissecting load-induced osteogenic pathways and mechanisms.

Organ culture systems are not a new concept and their use can be found in the literature throughout the last several decades. Mammalian organ culture systems have ranged from mouse and rat to pig and human and have included aortic, skeletal muscle, diaphragm, pancreatic, liver, tumor, cartilage and bone tissues (Lyubimov and Gotlieb 2004; Swanson et al. 2002; Del Rizzo et al. 2001; Takezawa et al. 2000; Voisard et al. 1999; Merrick et al. 1997; Wetzel and Salpeter 1991; Merrilees and Scott 1982; Jubb 1979; Barrett and Trump 1978; Stepita-Klauco and Dolezalova 1968). Culture durations have ranged from a few hours in bone systems to 14 and 18 weeks in arterial and aortic models, respectively. Not surprisingly, longer-term viability in the highly vascularized, compliant tissues has been more successful than in the harder tissues. For instance, cartilage models have generally not exceeded 1 week for neonatal models or 2 weeks for embryonic models (Ishizeki et al. 1995; Weiss et al. 1988). While the models vary greatly, the similar intent of these systems is to provide a more physiologically relevant culture system in comparison with cell culture, enable the study of isolated systems and enable structural studies.

Early experimental validation of the effects of mechanical loading on bone came from the embryologist Glucksmann using embryonic chick limbs under constrained growth in culture (Boyd 2005; Glucksmann 1942). While both cartilage and bone organ culture models have been developed, one of the earliest routine uses of bone organ cultures focused on their utilization in bone resorption assays and the measurement of radioactive calcium release during matrix degradation precipitated by resorptive agent administration (Fell et al. 1976; Raisz and Niemann 1967; Raisz 1965). To date, several organ systems have been utilized including calvarial, long and vertebral bones (Murrills 1996; Reynolds 1976). Organ culture models of the whole bone are much less common in mechanotransduction research than cell culture or in vivo approaches. Nonetheless, they have been used in short-term studies. For example, a single 20 min episode of bending (650 με @ 0.4 Hz) maintained the levels of alkaline phosphatase in tibiotarsi from embryonic chickens, when compared with nonloaded controls (Zaman et al. 1992). In addition, expression of collagen type I was significantly greater at 18 h following loading than at 4 h. In this study, the osteogenic response was elicited at strain magnitudes equivalent to those observed in vivo, in immature chicks (Zaman et al. 1992). Further, the loading effects observed in bones from embryonic chicks were similar to those seen in other species (Dallas et al. 1993). In particular, activation of PGE2-dependent signaling suggests the validity of organ culture for dissecting mechanotransduction pathways and mechanisms.

Our goal was to develop and validate a whole bone organ culture model to be utilized in biomimetic mechanotransduction research. For the whole bone organ culture modeling approach to mechanotransduction research to be successful, it is necessary to demonstrate that the organs remain viable in culture, grow and respond to mechanical stimulation with a response indicative of bone formation, such as an increase in structural properties (mechanical strength, stiffness) or matrix protein production (at the molecular and/or cellular levels). While an exhaustive evaluation of these models will require thorough histological, histomorphometrical, mechanical, and cellular and molecular analyses, in the current work, initial structural proof of concept is established for a novel whole bone organ culture system that utilizes neonatal rat femurs. The bones remain viable in culture, grow and respond to mechanical stimulation with structural adaptations that increase bone strength up to 7 days following loading in culture. In addition to short-term viability (<1 week), histology of the model out to 2 week in culture was also assessed to address the feasibility of the model for longerterm studies.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Organ culture system

Femurs were obtained from 2-day-old Wistar rat pups. Care was taken to minimize handling; blunt finger dissection was used to extract the bones with the periosteum intact, and all animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institute’s Animal Care and Use Committee. Upon harvesting, bones were weighed, measured via digital imaging techniques and placed in BGJb (Gibco) medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). To enable oxygen diffusion through the tissues, the bones were placed in 12-well culture dishes on sterile stainless steel mesh inserts to position them at the liquid/gas interface (Garrett 2003). Prior to reuse, meshes were washed in a mixture of distilled water and 10% nitric acid, rinsed in distilled water and baked for 1 h (Garrett 2003). Medium was added as needed to counteract daily evaporation and changed every 72 h. For growth and stimulation studies, bones were maintained in culture for a period of time not exceeding 8 days; for viability studies, bones were maintained in culture for a period of time not exceeding 15 days (Fig. 1).

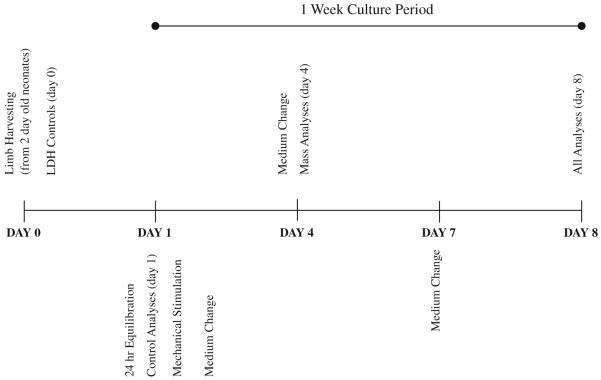

Fig. 1.

Timeline of analyses completed to validate the whole bone femur as a viable organ culture mechanotransduction model. In addition to the analyses in the timeline, LDH staining was completed at 15 days of culture

2.2 Assessment of organ culture viability

Bones were subjected to a variety of viability and growth analyses to verify adequate culture conditions. Alcian blue/alizarin red staining was completed to verify that the bone diaphysis was undergoing mineralization and contained calcium at 1 and 8 days in culture (Kimmel and Trammell 1981). Tissue viability via passive diffusion was established using a theoretical bone permeability analysis (Beno et al. 2006; Botchwey et al. 2003a,b). From scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of ashed bone at day 8, pore diameter, area, volume and number were determined. Based upon these numbers, the pore volume fraction was calculated as the ratio of pore to total bone (shaft) volume. Nutrient diffusion and consumption in the absence of active perfusion were determined by approximating osteocyte density (Botchwey et al. 2003a,b) and calculating Darcy’s permeability constant (Botchwey et al. 2003a,b) assuming a tortuosity of 2 (Steck and Knothe Tate 2004). Solving for nutrient diffusion, oxygen concentrations at the center of the cortical bone and endosteal surface were approximated and compared to concentrations at the periosteal surface. Topical dye tracer studies were completed to experimentally validate this approach. Utilizing a technique similar to that of Knothe Tate, bones were dyed with sterile procion red dye (0.8% MW 300–400 procion in a 10% v/v solution of culture medium). Bones were stained on day 1 or 8 for 6 h then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and cryosectioned. White light microscopy was used to verify passive dye diffusion (Knothe Tate et al. 1998).

To address osteocyte viability, 6 pr of femurs were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) staining. Manual osteocyte cell counts following H&E staining were completed to quantify the number of empty lacunae. For H&E staining, bones were maintained in culture for either 1 or 8 days at which time they were placed in fixative (10% buffered formalin for 24 h) then decalcified in Formical 2000 using an endpoint decalcification test comprised of a cocktail of ammonium oxylate and ammonium hydroxide. Once decalcified, the bones were placed in 70% ethanol and paraffin embedded. Bones were then sectioned at 5–10 microns, stained with H&E and assessed using white light microscopy for the presence of osteocytes in the lacunae. A minimum of 12 midshaft regions per section (200× magnification) and a minimum of 6 sections per bone were analyzed at each time point.

LDH is an enzyme catalyst of the lactate to pyruvate conversion in energy production and is therefore a useful approach to distinguish viable (LDH+) from nonviable (LDH−) osteocytes (Mann et al. 2006; Wong et al. 1982). To quantify the maximum cell viability, LDH controls were stained on day 0 within three hours of harvest and compared to bones at 1 week (day 8) and 2 week (day 15) of culture. For LDH staining, bones were washed in HBSS and incubated in nitroblue tetrazolium. After washing in distilled water, bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and decalcified in Formical 2000. Following decalcification, bones were washed and stored in 15% sucrose in HBSS at 4°C. Twenty-four hour prior to cryosectioning, the bones were transferred to a 50:50 mixture of OCT and 15% sucrose in HBSS for 24 h at 4°C. To ease visualization, bones were counterstained with methyl green and a weak eosin in 100% ethanol. Bones were cut into 5- to 10-micron-thick sections and assessed with light microscopy. Negative controls were analyzed following autoclave (Liebergall et al. 1998). A minimum of 12 midshaft regions per section (200× magnification) and a minimum of 6 sections per bone were analyzed at each time point for LDH+ and LDH− osteocytes.

2.3 Assessment of organ culture growth

To assess growth in culture, bone dimensions were determined using a Nikon dissecting microscope outfitted with a Nikon digital camera and analyzed with ImageJ software (NIH). Thirty-eight paired femurs were randomly assigned to measurement at day 1 or day 8, and overall femur lengths, shaft lengths and shaft diameters were determined from the average of three measurements. Twenty-four femur pairs were repetitively weighed on a balance (Sartorius CP64) to determine changes in wet, dry and ash weight occurring in culture between days 1 and 4 (8 pair), days 4 and 8 (8 pair), and days 1 and 8 (8 pair). Bones were weighed wet (wet weight), after being defatted in acetone (72 h) and air-dried (24 h) (dry weight), and after being heated to 600°C for 6 h in a muffle furnace (ash weight). Percent ash fraction was determined using previously established techniques (Mikic et al. 2002). Changes in cross-sectional morphology between days 1 and 8 were determined for 10 femoral pairs. For this analysis, bone shafts were embedded in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) following serial dehydration in alcohol, sectioned on a low-speed diamond saw (Isomet) and digitally imaged. Moments of inertia and cortical and medullary bone areas as a function of growth in culture were calculated using digital imaging techniques.

Changes in bone mineral density (BMD) in femoral pairs were also assessed through 72 h in culture to verify that bones were viable and capable of continued mineralization in culture, independent of stimulation. A Scanco vivaCT 40 scanner was used to assess cortical bone volume and density in the central diaphysis of 4 femurs at 24 h intervals from 0 to 72 h. Scans were acquired using machine settings of 45 kVP, 88 mA and integration time of 0.4 s. Images were reconstructed in 2,048 × 2,048 pixel matrices and stored in 3D arrays with an isotropic voxel size of 10.5 μm.

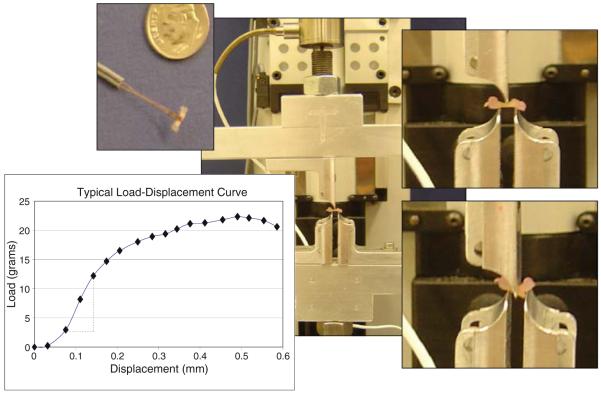

2.4 Mechanical stimulation

As previously described, a custom built small-scale loading platform was used for mechanical stimulation (Saunders and Donahue 2004; Saunders et al. 2006). Bones (8 pr) were loaded 24 h after harvest (day 1). One limb from each pair was randomly assigned to loading with the contralateral limb serving as a control. Bones were placed on padded three-point bend fixtures and oriented with the anterior cortex of the diaphysis in tension. Loaded bones underwent a single loading regime of 350 cycles (5 min) utilizing an oscillatory waveform and maximum and minimum compressive strain of 500 microstrain (με) and 50 με, respectively, with bone strain determined using fully bonded strain gauges placed on the anterior surface of the mid-diaphyseal bone shaft. The loading regime was based upon the in vivo loading of mouse tibiae in the mediolateral orientation for 70 cycles per day for 5 days (Gross et al. 2002). The total number of cycles (350) employed was the same as that previously used, but in the present case all cycles were applied in a single application to study the immediate, short-term responses, and organ cultures were loaded in the anteroposterior orientation. The latter modification was more appropriate to the true loading orientation of the bone in contrast to the mediolateral loading that was selected largely to separate effects from the experimental loading and normal ambulation in the animal models; a concern not applicable to the organ culture systems. Following mechanical stimulation, the bones were returned to culture for 1 week (day 8) after which they were subjected to structural analysis.

2.5 Assessment of organ culture mechanoresponse

Structural properties of the bones (day 8) were obtained from destructive mechanical testing utilizing the small-scale loading platform outfitted with a 50-g load cell and 25-mm displacement sensor. Bones were placed in the three-point bend fixtures in the same orientation as utilized for the stimulatory loading regime (without padded bumpers) and tested to failure utilizing a linear ramp waveform at 0.35 mm/s and a data acquisition rate of 10 Hz. Linear stiffness, defined as the slope of the load-displacement curve in the linear region, load to failure and failure location were determined.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Raw data were summarized and are presented as means and standard errors within bar charts or box plots. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc comparisons made using the Tukey (ordinary ANOVA) or Bonferroni (nonparametric ANOVA) methods. Nonparametric t-tests were executed when only two groups were compared. All analyses were accomplished with Instat software (GraphPad).

3 Results

3.1 Assessment of organ culture viability

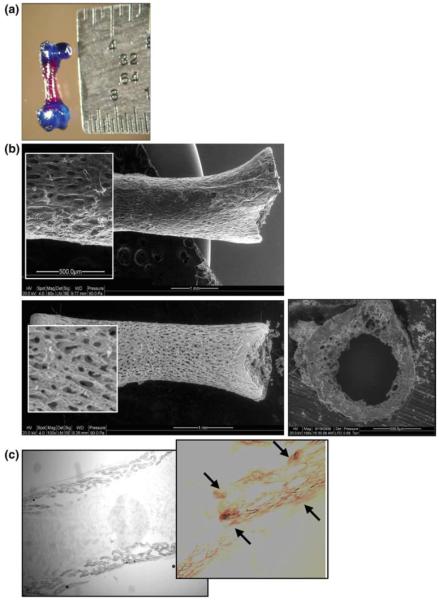

As shown in Fig. 2a, after 8 days in culture, the glycosaminoglycans in the cartilage stained blue while the bone shaft stained red, indicating mineralization; a similar result was found for day 1 femurs (data not shown). Thus, we concluded that while the neonatal bones were not fully calcified, mineralization was well underway making the model suitable for assessing osteogenic changes in response to mechanical stimulation. Diffusion calculations were based upon ashed bone shaft images acquired from SEM on femurs following 8 days of culture. The highly porous nature of the neonatal bones at this time point was visible in the resulting images (Fig. 2b). Solving for nutrient diffusion, oxygen concentrations at the center of the cortical bone and endosteal surface were determined to be within 1.5% of that at the periosteal surface (296 vs. 300 g/m3). Given the oxygen concentration at the inner bone surface was approximately equal to that of the outer bone surface, it was concluded that there was adequate passive diffusion for viability. This was further verified by topical procion red dye diffusion studies indicating dye penetration to the endosteal surface upon cryosection (Fig. 2c).

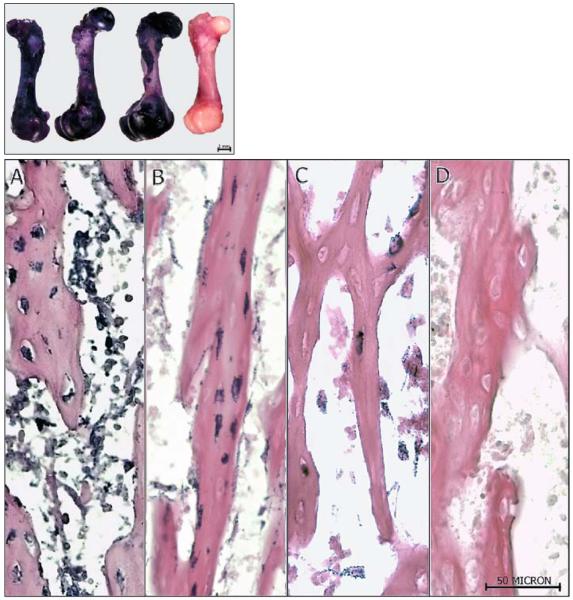

Fig. 2.

a Alician blue/alizarin red staining of day 8 femur depicting the red mineralized diaphysis contrasted with the blue staining cartilage. Presence of the calcium-rich shaft supports the model’s use as an organ culture system capable of osteogenesis. The neonatal system increases the likelihood of survival in culture given the incomplete mineralization present at this time point and the current use of passive diffusion. b SEM images collected to determine pore geometry and approximate the adequacy of passive oxygen diffusion in maintaining organ viability over the culture period. Top image of intact bone shaft prior to ashing, illustrating presence of the periosteum. Bottom image of ashed bone shaft showing the microporosity longitudinally and right transversely. Using these images, pore numbers and dimensions were approximated and used to calculate oxygen diffusion from the periosteal to the endosteal bone surface. c Procion red dye was added to intact cultures for 6 h, followed by snap-freezing and cryosectioning. White light microscopy was used to verify dye diffusion through the cortex

H&E staining showed the presence of osteocyte bodies in the majority of lacunae at both 1 and 8 days in culture, suggesting adequate organ culture viability at the cellular level. Specifically, from a total of 7,373 lacunae counted from day 1 bones, 8.3% (614) were empty. In contrast, from a total of 8,155 lacunae counted from day 8 bones, 21.7% (1,772) were empty. In addition, both osteoclasts and osteoblasts were found on the bone surfaces indicating turnover at day 1 and 8 (data not shown). While the H&E staining demonstrated the presence of the osteocytes, it was not a sufficient technique to verify osteocyte viability.

LDH stains were completed to quantify osteocyte viability (Table 1;Fig. 3). From LDH staining of the control bones analyzed immediately upon harvesting (day 0), it was determined that 92.7% of the lacunae housed viable osteocytes. In contrast, 69.8% of the lacunae housed viable osteocytes at day 8 of culture. Viability was severely compromised by day 15 where only 42.0% of the lacunae housed viable osteocytes.

Table 1.

Osteocyte viability quantified at 0, 8 and 15 days in culture

| Day 0 (A) | Day 8 (B) | Day 15 (C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viable osteocytes | 4,115 | 3,008 | 1,498 |

| Nonviable osteocytes | 296 | 1,173 | 1,763 |

| Empty lacunae | 27 | 131 | 301 |

| Cells (N) | 4,438 | 4,312 | 3,562 |

| Viable (%) | 92.7 | 69.8 | 42.0 |

| Nonviable (%) | 6.7 | 27.2 | 49.5 |

| Empty lacune (%) | 0.6 | 3.0 | 8.5 |

Fig. 3.

LDH staining demonstrating octeocyte viability for 0 (a), 8 (b) and 15 (c) days in culture. For control comparisons, LDH was quantified immediately following harvest (day 0) to determine the maximum viability of the cultures, and an autoclaved ‘dead’ explant d served as a negative control. In addition, while the 1-week (day 1) counts were completed to quantify the viability of the bones over the culture period in which mechanoresponsiveness was assessed, 2-week counts were completed to determine the rate at which these systems were dying under our culture conditions

3.2 Assessment of organ culture growth

Changes in bone dimensions as a function of time in culture are plotted in Fig. 4a–c. Analysis of overall femur length and shaft dimensions in 38 pr revealed significant increases in bone size as a function of time. Specifically, there was a 10.3% increase in femur length, a 6.3% increase in shaft length and a 6.5% increase in shaft diameter during the 8-day culture period. All time points were statistically significant. Changes in mass as a function of time in culture are plotted in Fig. 5a–c. Bones significantly increased in wet weight as a function of time in culture. Specifically, bone weights increased 33.8% between days 1 and 4; 38.4% between days 4 and 8; and 85.2% between days 1 and 8. All time points were statistically significant. In addition, dry weight increased 17.9% between days 1 and 4; 26.9% between days 4 and 8; and 49.5% between days 1 and 8. The increase in dry weight between days 1 and 8 was statistically significant. Ash weight increased 14.9% between days 1 and 4; 37.0% between days 4 and 8; and 57.5% between days 1 and 8. Ash weight comparisons between days 1 and 8 were statistically significant. Ash fractions from days 1, 4 and 8 in culture were 18.7, 18.2 and 19.6%, respectively. Assessing changes in wet, dry and ash weights, it was found that on day 1, dry weight was reduced 82.3% from wet weight and ash weight was reduced 96.7% from wet weight and 81.4% from dry weight. Similar trends were noted for day 8 where dry weight was reduced 85.7% from wet weight and ash weight was reduced 97.2% from wet weight and 80.4% from dry weight. Thus, it was apparent that cartilage and tissue hydration accounted for the majority of the bone weight in the organ cultures. However, given the similar ash fractions as a function of time in culture and the continued increase in dry and ash weight, it was concluded that the bones continued to grow in culture over the duration of the experimental studies. Furthermore, to verify that the growth in culture was due to cell-mediated phenomena, ‘dead’ explants (Meghji et al. 1998) frozen and thawed three times on day 1 were cultured and assessed for growth on day 8. Dimensions from 3 pr of dead femurs on day 8 were not significantly different from their day 1 counterparts but were significantly smaller than their nonfrozen, organ culture day 8 counterparts (data not shown).

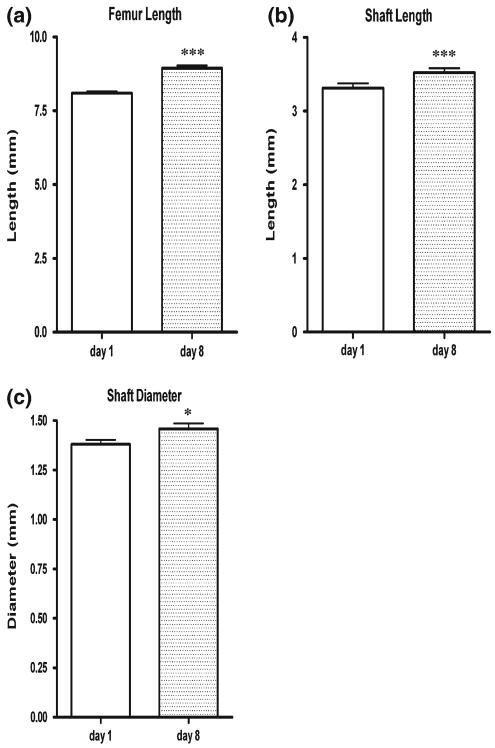

Fig. 4.

Bone growth in culture—dimensional changes. a Increases in femur length during the 1-week culture period. b Increases in shaft length during the 1-week culture period. c Increases in shaft diameter during the 1-week culture period. Bone and shaft lengths and shaft diameter increases from day 1 to 8 were statistically significant ( p < 0.001 and p < 0.05). All values are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 38 pr)

Fig. 5.

Bone growth in culture—weight changes. a Increases in whole bone wet weight between days 1, 4 and 8 in organ culture. b Increases in dry bone weight between days 1, 4 and 8 in organ culture. c Increases in ash bone weight between days 1, 4 and 8 in organ culture. Wet weights at day 8 were statistically larger ( p < 0.05) than day 1 and day 4 weights; dry and ash weights at day 8 were statistically larger ( p < 0.05) than ash weights at day 1. All values are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 24 pr). d Photograph of ashed bone shaft depicting mineralized matrix

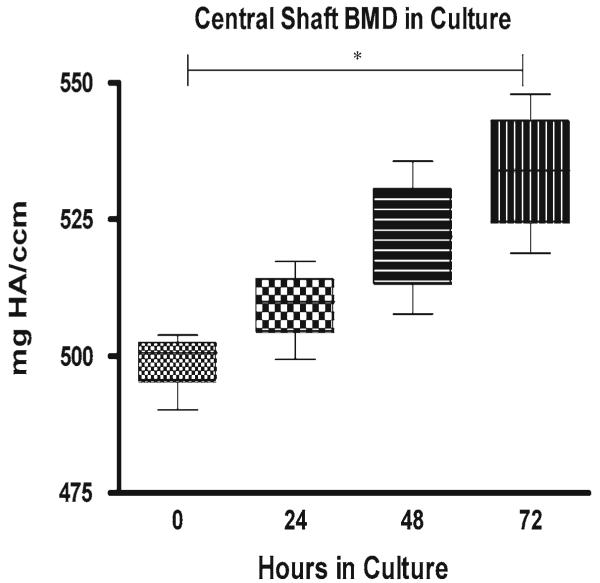

Cross-sectional properties also significantly increased with time in culture (Fig. 6a–b). Moments of inertia (Ixx and Iyy) increased 40.9 and 34.9% in culture, while the polar moment of inertia (Jo) increased 37.7% and cortical and medullary area increased 16.6 and 17.3%, respectively. All comparisons with the exception of medullary area were statistically significant. From microCT scans on four bones at 24 h intervals from 0 to 72 h, bone shaft BMD, expressed as mg hydroxyapatite/cm3 (mgHA/ccm), was also found to steadily increase (Fig. 7). Specifically, BMD increased 2.1% at 24 h, 4.6% at 48 h, and 7.0% at 72 h. BMD increases from 0 to 72 h were statistically significant and further verified the incomplete mineralization of our model in contrast to fully mineralized bone with a BMD value on the order of 1,200 mgHA/ccm (Krug et al. 2008). In contrast to standard DEXA-based BMD quantification, the microCT approach yielded a true volumetric measurement of BMD (Koller and Laib 2007). These studies showed that the organ cultures in the absence of stimulation could be kept viable and continued to grow in culture during the initial days of the culture period when inflammatory pathways were activated by harvesting trauma. Based upon these results, we concluded that the organ culture model was viable, growing and adequately nourished via diffusion during the culture period.

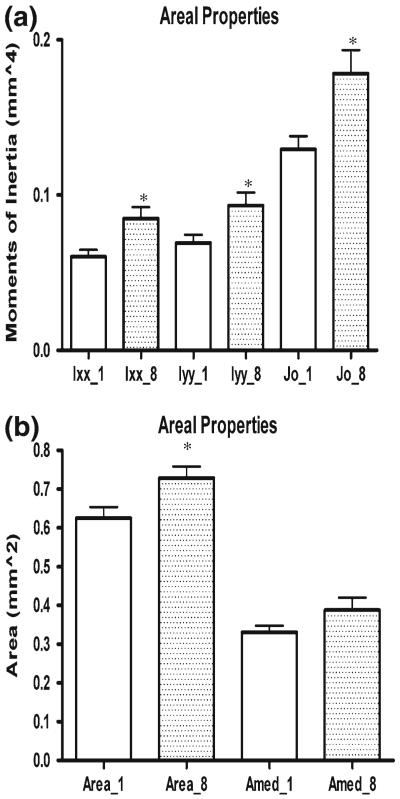

Fig. 6.

Bone growth in culture—areal changes. a Increases in moment of inertia (Ixx and Iyy) and polar moment of inertia (Jo) between days 1 and 8. All increases were statistically significant ( p < 0.05). b Increases in cortical area (Area) and medullary area (Amed) between days 1 and 8. Increases in cortical area (Area) were statistically significant (p < 0.05). All values are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 10 pr)

Fig. 7.

BMD increases in organ culture from time of harvest (0) to 72-h (72) post-harvest. All bones (n = 4) demonstrated a steady increase in shaft BMD with changes between 0 and 72 h statistically significant (p < 0.05)

3.3 Assessment of organ culture mechanoresponse

Destructive mechanical testing results are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 8 for 8 bone pr. Three-hundred and fifty cycles of stimulation increased bending stiffness 34.5%, increased failure load 5.8% and decreased failure displacement 11.2%. Increases in stiffness were significant (p < 0.1). With the exception of one control specimen, all fractures occurred midshaft. The increases in stiffness and failure load with a corresponding decrease in displacement would support an increase in bone strength as a result of mechanical stimulation. Based upon these results, we concluded that the organ culture model was mechano-responsive.

Table 2.

Structural increases in strength determined by mechanical testing

| Stiffness (gm/mm) | Load (gm) | Displacement (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulated | 111.3 ± 6 | 23.3 ± 1 | 0.48 ± 1 |

| Control | 82.8 ± 9 | 22.0 ± 1 | 0.54 ± 1 |

Structural properties are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 8 pr). Mechanical stimulation significantly increased bone stiffness (p < 0.1)

Fig. 8.

A typical load-displacement curve. Structural properties were determined from 3-point bending on day 8; fractures were shaft fractures. Bending stiffness (slope of linear region defined by dashed lines), failure load and failure displacement were determined

4 Discussion

We set out to develop an organ culture system that could maintain whole bone viability under basic culture conditions in the absence of anabolic agents. In addition, it was important to develop a model using a long bone in which aspects of cell communication and signaling retain their 3D relationships of tissues and cells in vivo and which demonstrates mechanosensitivity (Alam et al. 2005; Hagino et al. 2005; Gibson et al. 2004; Watanuki et al. 2002; Carter and Orr 1992; Turner and Bell 1986). Because the embryonic organ culture has a natural tendency for activation of resorption, it has been used largely to test the efficacy of anti-resorptive agents (Raisz and Niemann 1967; Raisz 1965). Our goal was to prove that the model could be maintained in a viable state for osteogenic studies, in which some growth and development continues and supports the application of mechanical stimuli. Although we anticipated that the efficiency of diffusion would decrease with increasing age of the model, the embryonic bone was too soft and lacked the structural integrity needed in a mechanotransduction model. Harvesting femurs from Wistar rats 1 and 2 days post-birth, we determined that the 1-day-old neonates were also easily damaged upon harvesting and thus likely to have unintentional inflammatory responses and elevated PGE2 levels (Meghji et al. 1998) perhaps expediting bone resorption. Therefore, we used a model of the neonatal rat femur taken from 2-day-old Wistar pups. Given the neonatal state of the model, animals were not sexed. While the age matching of the neonatal rat model to a human equivalent is not an exact science (Quinn 2005), we approximated the age of our rat model to represent the neonatal state of childhood development. Thus, our model would be an appropriate model for neonatal issues such as examining the role of mechanotransduction in neonatal airway obstruction treated by mechanical distraction. We acknowledge that this model, as described, is not appropriate for addressing mechanotransduction mechanisms in mature bone. Moreover, given that age-matched controls were not included in this study, we are not able to quantifiably assess the effect of culture on this model. However, our current studies in a 5-day-old neonatal model investigating mechanical distraction would suggest a significant decrease in all properties of the culture model in comparison with their age-matched counterparts (data not shown). While not surprising, we find it a good indication/justification that our present development of a perfusion chamber to enhance organ culture viability is necessary.

Differences in the H&E and LDH results may be attributed to differences in technique. For instance, while the H&E staining was completed using 10% buffered formalin fixative, the LDH required a rapid fixative infiltration using 4% paraformaldehyde. Not surprisingly, the more rapid infiltration of the LDH technique resulted in a decrease in empty lacunae. Furthermore, whereas the H&E stains were completed to correlate with the time points chosen to assess growth and mechanoresponsiveness, the LDH stains were completed to quantify viability in its extreme. That is, viability was assessed immediately post-harvest (maximum viability) and at 15 days in culture (minimum viability). The latter data would suggest that longer-term organ culture studies would need to incorporate a method to increase culture viability such as active perfusion and/or topical stimulants and that future studies utilize paraformaldehyde for all fixation procedures.

Organ culture models offer a unique environment in which bone cell responses and interactions may be studied. While mechanically loaded bone has been studied in culture, whole bones have typically been maintained in culture for only short durations or cored into explants maintaining long-term viability by, among other things, utilizing trabecular bone plugs (Chan et al. 2009; Davies et al. 2006; Takai et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2003). For example, Guo’s group, utilizing bovine metacarpal trabecular explants subjected to pressure showed that osteocyte viability was enhanced by mechanical load and that the osteocyte–osteoblast interactions enhanced osteoblast response (Takai et al. 2004). In more recent explant work, they demonstrated the importance of cell–cell heterotypic communication between osteocytes and osteoblasts in bone mechanoresponsiveness (Chan et al. 2009). These studies, not unlike our previous in vitro work, examined relationships between cell communication, prostaglandin E2response and mechanical stimulation (Taylor et al. 2007; Saunders et al. 2001, 2003) and further support the need for biomimetic mechanotransduction systems to study multicellular interactions in a native, 3D milieu. However, the use of the trabecular bone, while providing for increased viability eliminated the periosteum, which has proven to be important (El Haj et al. 2009; Stevens et al. 2005). In the current work, we laid the foundation for the utilization of whole bone organ culture models (with intact periosteum) in mechanotransduction research. While long-term goals include the development of adult bone models, the neonatal system with its incomplete mineralization was conducive to viability maintenance without augmentative perfusive strategies. Here, the preliminary proof of concept of using whole bone cultures in mechanotransduction research has been established as it has been demonstrated that the bones remain viable in culture, grow and are responsive to mechanical stimulation. While continued work is necessary to refine these testing techniques and expand analysis to include cellular and molecular activity, preliminary structural results would support the use of whole bone organ culture systems in mechanotransduction research.

Simply stated, for bone to respond to mechanical loading, bone cells must be able to sense and respond to the mechanical stimulus such that bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts can coordinate their activity. Bone cellular mechanotransduction is the process by which bone cells sense and respond to a physical stimulus. For in vitro mechanotransduction studies, cells are generally isolated as primary cells from bone or obtained from immortalized lines and seeded on an artificial matrix. They are grown to relative confluence, controlling for pH, CO2 and temperature and then subjected to mechanical stimulation by various means, including poke, stretch, bending and shear. As previously detailed (Brown 2000), these stimulation methods vary greatly in the amount of control one has over the stimulus, its reproducibility and its ability to be quantified. At the macroscopic scale, one of the more reproducible loading modes is fluid shear. Physiologically, the use of fluid shear as a stimulus is an extension of the premise put forth by Piekarski and Munro (1977), in which osteocytes embedded in the bone matrix, housed within lacunae and bathed by interstitial fluid would be subjected to fluid forces as bone loading resulted in shifts in fluid pressure gradients (Piekarski and Munro 1977). While it has been 30 years since Piekarski originally proposed a role for fluid flow in bone cell responsiveness, it is only recently that researchers have come to appreciate and routinely utilize fluid shear in bone cell stimulation studies. However, the biological foundation on which these systems are based is out of date. That is, as we learn more about bone adaptation in response to mechanical loading, there is a significant volume of research that would suggest that osteocytes, residing within the bone matrix, are able to ‘detect’ the mechanical load and communicate the signal to osteoblasts and osteoclasts that are able to ‘effect’ a response. Evidence suggests that signals may be communicated from osteocytes directly to osteoclasts and osteoblasts (Bonewald 2007). Current in vitro systems do not address these interactions, failing to correctly mimic the biological environment. For instance, in general, in vitro cell models utilize single cell types (osteocyte or osteoblast) in monolayer, dissociate the cells from the extracellular matrix and do not correctly preserve the 3D architecture of the osteocyte and osteoblast communication networks found in living bone. With respect to the first two issues, the utilization of the cells in monolayer falls short of adequately representing the 3D architecture of the bone matrix. Artificial substrates, such as glass or plastic, are generally utilized and in the event that protein coatings are applied to the substrate, the intention is often to increase adherence of the cells to the substrate and not to enable examination of the cell–matrix interactions. In addition, these systems do not incorporate the 3D communication networks present in bone, and more recent data support the importance of studying the multicellular (osteocyte/osteoblast/osteoclast) interactions in bone in response to loading. Thus, to advance the bone biology field, it is essential that we develop biomimetic models that incorporate and accurately mimic the bone environment. Inherently, the organ culture models accomplish this task, and as such, we believe the organ culture approach may provide valuable insights into mechanotransduction mechanisms and pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Glen O Njus, Associate Professor, The University of Akron (1953–2009). Funding for this project was provided by awards from The Life Sciences Greenhouse of Central PA; The Whitaker Foundation; and, National Institutes of Health (K25AG022464).

Contributor Information

Marnie M. Saunders, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA

Linda A. Simmerman, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA

Gretchen L. Reed, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA

Neil A. Sharkey, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA

Amanda F. Taylor, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA

References

- Alam I, Warden SJ, Robling AG, Turner CH. Mechanotransduction in bone does not require a functional cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20(3):438–446. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LA, Trump BF. Maintaining human aortas in long-term organ culture. Meth Cell Sci. 1978;4(13):861–862. [Google Scholar]

- Beno T, Yoon Y, Cowin SC, Fritton SP. Estimation of bone permeability using accurate microstructural measurements. J Biomech. 2006;39(13):2378–2387. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonewald LF. Osteocytes as dynamic multifunctional cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1116:281–290. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchwey EA, Dupree MA, Pollack SR, Levine EM, Laurencin CT. Tissue engineered bone: measurement of nutrient transport in three-dimensional matrices. Wiley; 2003a. pp. 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchwey EA, Pollack SR, El-Amin S, Levine EM, Tuan RS, Laurencin CT. Human osteoblast-like cells in three-dimensional culture with fluid flow. Biorheology. 2003b;40:299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JD. Embryology in war-time Britain. Anat Rec. 2005;87(1):91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TD. Techniques for mechanical stimulation of cells in vitro: a review. J Biomech. 2000;33(1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter DR, Orr TE. Skeletal development and bone functional adaptation. J Bone Miner Res Suppl. 1992;2:S389–S395. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650071405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan ME, Lu XL, Huo B, Baik AD, Chiang V, Guldberg RE, Lu HH, Guo XE. A trabecular bone explant model of osteocyte-osteoblast co-culture for bone mechanobiology. Cell Molec Bioeng. 2009;2(3):405–415. doi: 10.1007/s12195-009-0075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas SL, Zaman G, Pead MJ, Lanyon LE. Early strain-related changes in cultured embryonic chick tibiotarsi parallel those associated with adaptive modeling in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(3):251–259. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CM, Jones DB, Stoddart MJ, Koller K, Smith E, Archer CW, Richards RG. Mechanically loaded ex vivo bone culture system ‘Zetos’: systems and culture preparation. Eur Cell Mater. 2006;11:57–75. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v011a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rizzo DF, Moon MC, Werner JP, Zahradka P. A novel organ culture method to study intimal hyperplasia at the site of a coronary artery bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1273–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Haj AJ, Hampson K, Gogniat G. Bioreactors for connective tissue engineering: design and monitoring innovations. Adv Biochem Eng/Biotechnol. 2009;112:81–93. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69357-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell HB, Balls M, Monnickendam MA. Organ culture in biomedical research. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett R. Assessing bone formation using mouse calvarial organ cultures. In: Helfrich MH, Ralston SH, editors. Bone research protocols. Humana Press; Totowa: 2003. chap 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JH, Mitchell A, Harries MG, Reeve J. Nutritional and exercise-related determinants of bone density in elite female runners. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(8):611–618. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glucksmann A. The role of mechanical stresses in bone formation in vitro. J Anat. 1942;76:231–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross TS, Srinivasan S, Liu CC, Clemens TL, Bain SD. Non-invasive loading of the murine tibia: an in vivo model for the study of mechanotransduction. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(3):493–501. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagino H, Kuraoka M, Kameyama Y, Okano T, Teshima R. Effect of a selective agonist for prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP4 (ONO-4819) on the cortical bone response to mechanical loading. Bone. 2005;36(3):444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillam RA, Skerry TM. Inhibition of bone resorption and stimulation of formation by mechanical loading of the modeling rat ulna in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10(5):683–689. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizeki K, Takigawa M, Harada Y, Suzuki F, Nawa T. Meckel’s cartilage chondrocytes in organ culture synthesize bone-type proteins accompanying osteocytic phenotype expression. Anat Embryol. 1995;185:421–430. doi: 10.1007/BF00186834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DB, Broeckmann E, Pohl T, Smith EL. Development of a mechanical testing and loading system for trabecular bone studies for long term culture. Eur Cell Mater. 2003;5:48–60. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v005a05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubb RW. Effect of hyperoxia on articular tissues in organ culture. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979;38(3):279–286. doi: 10.1136/ard.38.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CA, Trammell C. A rapid procedure for routine staining of cartilage and bone in fetal and adult animals. Stain Technol. 1981;56(5):271–273. doi: 10.3109/10520298109067325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knothe Tate ML, Niederer P, Knothe U. In vivo tracer transport through the lacunocanalicular system of rat bone in an environment devoid of mechanical loading. Bone. 1998;22(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller B, Laib A. Advanced bioimaging technologies in assessment of the quality of bone and scaffold materials: techniques and applications. Springer; 2007. Calibration of micro-CT data for quantifying bone mineral and biomaterial density and microarchitecture; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Krug R, Carballido-Gamio J, Burghardt AJ, Kazakia G, Hyun BH, Jobke B, Banerjee S, Huber M, Link TM, Majumdar S. Assessment of trabecular bone structure comparing magnetic resonance imaging at 3 Tesla with high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography ex vivo and in vivo. Osteoporos Int. 2008;29:653–661. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebergall M, Simkin A, Mendelson S, Rosenthal A, Amir G, Segal D. Effect of moderate bone hyperthermia on cell viability and mechanical function. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;349:242–248. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199804000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubimov EV, Gotlieb AI. Smooth muscle cell growth monolayer and aortic organ culture is promoted by a nonheparin binding endothelial cell-derived soluble factors. Cardiovas Pathol. 2004;13(3):139–145. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(04)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann V, Huber C, Kogianni G, Jones D, Noble B. The influence of mechanical stimulation on osteocyte apoptosis and bone viability in human trabecular bone. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6(4):408–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghji S, Hill PA, Harris M. Bone organ cultures. In: Henderson B, Arnett T, editors. Methods in bone biology. Thomson Science; New York: 1998. chap 4. [Google Scholar]

- Merrick AF, Shewring LD, Cunningham SA, Gustafsson K, Fabre JW. Organ culture of arteries for experimental studies of vascular endothelium in situ. Transpl Immunol. 1997;5(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(97)80019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrilees MJ, Scott L. Organ culture of rat carotid artery: maintenance of morphological characteristics and of pattern of matrix synthesis. In Vitro. 1982;18(11):900–910. doi: 10.1007/BF02796346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikic B, Battaglia TC, Taylor EA, Clark RT. The effect of growth/differentiation factor-5 deficiency on femoral composition and mechanical behavior in mice. Bone. 2002;30(5):733–737. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00699-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrills RJ. In vitro bone resorption assays. In: Bilezekian JP, Raisz LG, Rodan GA, editors. Principles of bone biology. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. chap 90. [Google Scholar]

- Piekarski K, Munro M. Transport mechanism operating between blood supply and osteocytes in long bones. Nature. 1977;269:80–82. doi: 10.1038/269080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn R. Comparing rat’s to human’s age: how old is my rat in people years? Nutrition. 2005;21:775–777. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisz L. Bone resorption in tissue culture. Factors influencing the response to parathyroid hormone. J Clin Inv. 1965;44:103–116. doi: 10.1172/JCI105117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisz L, Niemann I. Early effects of PTH and thyrocalcitonin in bone organ culture. Nature. 1967;214:486–488. doi: 10.1038/214486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JJ. Organ cultures of bone: studies on the physiology and pathology of resorption. In: Balls M, Monnickendam M, editors. Organ culture in biomedical research. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1976. pp. 355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin CT, Lanyon LE. Regulation of bone formation by applied dynamic loads. J Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin CT, Lanyon LE. Regulation of bone mass by mechanical strain magnitude. Calcif Tissue Int. 1985;37:411–417. doi: 10.1007/BF02553711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders MM, Donahue HJ. Development of a cost-effective loading machine for biomechanical evaluation of mouse transgenic models. Med Eng Phys. 2004;26:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders MM, You J, Trosko JE, Yamasaki H, Donahue HJ, Jacobs CR. Gap junctions and fluid flow in MC3T3-E1 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281(6):1917–1925. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders MM, You J, Zhou Z, Li Z, Yellowley CE, Kunze E, Jacobs CR, Donahue HJ. Fluid-flow induced prostaglandin E2 response of osteoblastic ROS 17/2.8 cells is gap junction-mediated and independent of cytosolic calcium. Bone. 2003;32(4):350–356. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders MM, Taylor AF, Du C, Zhou Z, Pellegrini VD, Jr, Donahue HJ. Mechanical stimulation effects on functional end effectors in osteoblastic MG-63 cells. J Biomech. 2006;39(8):1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck R, Knothe Tate ML. Application of stochastic network models for the study if molecular transport process in bone; Proceedings 2004 ASME international mechanical engineering congress and exposition (IMECE2004-59746).2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stepita-Klauco M, Dolezalova H. Organ culture of skeletal muscle subjected to intermittent activity. Biomed Lif Sci. 1968;24(9):971. doi: 10.1007/BF02138691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M, Marini RP, Schaefer D. In vivo engineering of organs. Bone Bioreactor. 2005;102(32):11450–11455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504705102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson N, Javed Q, Hogrefe K, Gershlick A. Human internal mammary artery organ culture model of coronary stenting: a novel investigation of smooth muscle cell response to drug-eluting stents. Clin Sci. 2002;103(4):347–353. doi: 10.1042/cs1030347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai E, Mauck RL, Hung CT, Guo XE. Osteocyte viability and regulation of osteoblast function in a 3D trabecular bone explant under dynamic hydrostatic pressure. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(9):1403–1410. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa T, Inoue M, Aoki S, Sekiguchi M, Wada K, Anazawa H, Hanai N. Concept of organ engineering: a reconstruction method of rat liver for in vitro culture. Tiss Eng. 2000;6(6):641–650. doi: 10.1089/10763270050199587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AF, Saunders MM, Shingle D, Cimbala JM, Zhou Z, Donahue HJ. Osteocytes communicate fluid flow-mediated effects to osteoblasts altering their phenotype. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C545–C552. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00611.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CH, Akhter MP, Raab DM, Kimmel DB, Recker RR. A noninvasive in vivo model for studying strain adaptive bone remodeling. Bone. 1991;12:73–79. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(91)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Bell NH. The effects of immobilization on bone histomorphometry in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1986;1(5):399–407. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisard R, v Eicken J, Baur R, Gschwend JE, Wenderoth U, Kleinschmidt K, Hombach V, Hoher M. A human arterial organ culture model of postangioplasty restenosis: results up to 56 days after ballooning. Atherosclerosis. 1999;144(1):123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanuki M, Sakai A, Sakata T, Tsurukami H, Miwa M, Uchida Y, Watanabe K, Ikeda K, Nakamura T. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in skeletal adaptation to acute increases in mechanical loading. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(6):1015–1025. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss A, Livne E, von der Mark K, Heinegard D, Silbermann M. Growth and repair of cartilage: organ culture system utilizing chondroprogenitor cells of condylar cartilage in newborn mice. J Bone Miner Res. 1988;3(1):93–100. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650030114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel DM, Salpeter MM. Fibrillation and accelerated A Ch R degradation in long-term muscle organ culture. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14(10):1003–1012. doi: 10.1002/mus.880141012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SY, Dunstan CR, Evans RA, Hills E. The determination of bone viability: a histochemical method for identification of lactate dehydrogenase activity in osteocytes in fresh calcified and decalcified sections of human bone. Pathology. 1982;14(4):439–442. doi: 10.3109/00313028209092124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman G, Dallas SL, Lanyon LE. Cultured embryonic bone shafts show osteogenic responses to mechanical loading. Calcif Tissue Int. 1992;51(2):132–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00298501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]