Abstract

Objective

Low Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) concentrations have been observed in impaired fasting glucose (IFG). It is uncertain if these abnormalities contribute directly to the pathogenesis of IFG and impaired glucose tolerance. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors raise incretin hormone concentrations enabling an examination of their effects on glucose turnover in IFG.

Research Design and Methods

We studied 22 subjects with IFG using a double blind, placebo-controlled parallel group design. At the time of enrollment, subjects ate a standardized meal labeled with [1-13C]-glucose. Infused [6-3H] glucose enabled measurement of systemic meal appearance (MRa). Infused [6,6-2H2] glucose enabled measurement of endogenous glucose production (EGP) and glucose disappearance (Rd). Subsequently, subjects were randomized to100mg of sitagliptin daily or placebo. After an 8-week treatment period, the mixed meal was repeated.

Results

As expected, subjects with IFG who received placebo did not experience any change in glucose concentrations. Despite raising intact GLP-1 concentrations, treatment with sitagliptin did not alter either fasting or postprandial glucose, insulin or C-peptide concentrations. Postprandial EGP (18.1±0.7 vs. 17.6±0.8 µmol/kg/min, p = 0.53), Rd (55.6±4.3 vs. 58.9±3.3 µmol/kg/min, p = 0.47) and MRa (6639±377 vs. 6581±316 µmol/kg per 6h, p = 0.85) were unchanged. Sitagliptin was associated with decreased total GLP-1 implying decreased incretin secretion.

Conclusions

DPP-4 inhibition did not alter fasting or postprandial glucose turnover in people with IFG. Low incretin concentrations are unlikely to be involved in the pathogenesis of IFG.

Keywords: sitagliptin, impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, incretins, insulin action, glucagon

Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) confers a high risk of progression to diabetes [1]. Its pathogenesis has been an area of active investigation, with defects in insulin and glucagon secretion as well as insulin action likely to play a role [2]. Several studies have suggested that the prediabetic [3] and diabetic [4] state are associated with alterations in circulating incretin concentrations. More recently, a large study of non-diabetic individuals demonstrated decreased GLP-1 concentrations after a glucose challenge in individuals with prediabetes but concluded that defects in GLP-1 secretion were unrelated to insulin secretion [5]. In impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), defects in incretin-induced insulin secretion coexist with defects in glucose induced insulin secretion [6].

Worsening degrees of glucose tolerance are associated with decreased insulin secretion for the prevailing insulin action. Moreover early glucagon suppression is impaired in IGT [2]. Since GLP-1 is an insulin secretagogue and suppresses glucagon, it is conceivable that defects in GLP-1 secretion could contribute to the pathogenesis of pre-diabetes. Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4), an enzyme which rapidly degrades the incretin hormones, has been shown to be a useful therapeutic strategy in type 2 diabetes [7]. DPP-4 inhibitors increase (model-calculated) insulin secretion and decrease glucagon concentrations resulting in a lowering of fasting (and postprandial) glucose concentrations in people with type 2 diabetes [8]. Their effects in people with IFG are less certain [9, 10]. However, DPP-4 inhibitors provide an opportunity to directly examine the contribution of abnormal incretin concentrations to the pathogenesis of IFG, by raising concentrations of endogenous incretin hormones.

The current experiments tested this hypothesis by measuring insulin secretion and action and fasting and postprandial glucose turnover before and after 8 weeks of therapy with a DPP-4 inhibitor.

Research Design and Methods

Subjects

After approval from the Mayo Institutional Review Board, 22 subjects with a fasting glucose > 5.5mmol/L (99mg/dL) but < 7.0mmol/L (125mg/dl) on two or more occasions, gave written informed consent to participate in the study. All subjects were in good health, at stable weight and did not engage in regular vigorous exercise. Subjects had no history of diabetes or of prior therapy with anti-diabetic medication. All subjects were instructed to follow a weight maintenance diet containing ~55% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 15% protein for the period of study. Body composition was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DPX scanner; Lunar, Madison, WI).

Experimental Design

We utilized a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled parallel group design. After a baseline meal study, subjects received either sitagliptin 100mg or an identical placebo taken before breakfast over an eight-week treatment period. Participants underwent a second meal study at the end of the treatment period (when they received study medication prior to meal ingestion). Participants were assessed in the Clinical Research Unit (CRU) 4 weeks after the first study when compliance was assessed by counting remaining medication. The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov. Identifier: NCT00364377.

Subjects were admitted to the CRU at 1700 on the evening prior to the meal study. Subsequently, they consumed a standard 10 cal/kg meal (55% carbohydrate, 30% fat and 15% protein) after which they fasted overnight. At 0630 (−210 minutes), a forearm vein was cannulated with an 18g needle to allow infusions to be performed. An 18g cannula was inserted retrogradely into a vein of the dorsum of the contra-lateral hand. This was placed in a heated Plexiglas box maintained at 55°C to allow sampling of arterialized venous blood. At −180 minutes, a primed (12mg/kg) continuous (0.12mg/kg/min) infusion of [6,6-2H2] glucose was initiated. Study medication was administered at −30 minutes on the second study day. At time 0, subjects consumed a meal consisting of 3 scrambled eggs, 55g of Canadian bacon, 240ml of water and Jell-O containing 75g of glucose labeled with [1-13C] glucose – (4% enrichment). The meal provided 510 Kcal (61% carbohydrate, 19% protein and 21% fat). An infusion of [6-3H] glucose was started at this time, and the infusion rate varied to mimic the anticipated appearance of meal [1-13C] glucose [8]. The rate of infusion of the [6,6-2H2] glucose was altered to approximate the anticipated fall in endogenous glucose production [8].

Analytical techniques

Plasma samples were placed on ice, centrifuged at 4°C, separated, and stored at −20°C until assayed. Glucose concentrations were measured using a glucose oxidase method (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma insulin was measured using a chemiluminescence assay (Access Assay; Beckman, Chaska, MN). Plasma glucagon and C-peptide were measured by Radio-Immunoassay (Linco Research, St. Louis, MO). Collection tubes for GIP and GLP-1 had 100 µM of DPP-4 inhibitor (Linco Research, St. Louis, MO) added. Total and intact GLP-1 and GIP concentrations were measured using C-terminal and N-terminal assays [11, 12]. Plasma [6,6-2H2] glucose and [1-13C] glucose enrichments were measured using gas chromatographic mass spectrometry (Thermoquest, San Jose,CA) to simultaneously monitor the C-1 and C-2 and C-3 to C-6 fragments, as described by Beylot et al. [13]. In addition, [6-3H] glucose specific activity was measured by liquid scintillation counting following deproteinization and passage over anion and cation exchange columns [8].

Calculations

The systemic rates of meal appearance (Rameal), endogenous glucose production (EGP) and glucose disappearance (Rd) were calculated using Steele’s two compartment model [14]. Rameal was calculated by multiplying rate of appearance of [1-13C] glucose (obtained from the infusion rate of [6-3H] glucose and the clamped plasma ratio of [6-3H] glucose and [1-13C] glucose) by the meal enrichment. EGP was calculated from the infusion rate of [6,62H2] glucose and the ratio of [6,62H2] glucose to endogenous glucose concentration. Glucose disappearance was calculated by subtracting the change in glucose mass from the overall rate of glucose appearance (i.e. Rameal + EGP). Values from –30 to 0 minutes were averaged and considered as basal. Area above basal was calculated using the trapezoidal rule.

Net insulin sensitivity (SI) was measured using the oral minimal model [15]. β-Cell responsivity indexes were estimated using the oral C-peptide minimal model [16], incorporating age-associated changes in C-peptide kinetics [17]. The model assumes that insulin secretion is comprised of a static (ϕstatic) and dynamic (ϕdynamic) component [16]. Disposition indices (DI) were calculated by multiplying ϕtotal, ϕdynamic, and ϕstatic, by SI.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Paired comparisons (within groups) to examine differences between the baseline study and after 8-weeks of treatment were made using Student’s two-tailed t-test for paired samples. Between-group comparisons were made using Student’s two-tailed t-test for unpaired samples. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Given the previously observed variation in fasting glucose in this and prior experiments [8], a sample size of 11 subjects provided > 99% power to detect a 1.0mmol/l difference in fasting glucose and 80% power to detect a 0.6mmol/l difference using a two-sided test with an α of 0.05.

Results

Volunteer Characteristics

Participants were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive sitagliptin or placebo. For baseline characteristics see Table 1. Both at baseline and post-intervention, there was a trend to between group (Placebo vs. Sitagliptin) differences in total weight and lean body mass. However there were no within-group differences over the course of treatment or no between-group differences in % change ((Post-intervention value – baseline value)/ baseline value) – expressed as a percentage - Please see supplementary table 1 for additional information).

Table 1. Group Characteristics.

Group Characteristics before and after intervention

| Placebo | Sitagliptin | P# | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M / F) | 3 / 8 | 1 / 10 | |

| Age (Years) | 54.1 + 2.4 | 55.2 + 2. 5 | 0.77 |

| FPG (mmol/l) | 6.11 + 0.08 | 6.12 + 0.10 | 0.97 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.6 + 0.1 | 5.4 + 0.1 | 0.16 |

| Baseline Weight (Kg) | 95.2 + 2.7 | 84.6 + 4.4 | 0.08 |

| Post-Intervention Weight (Kg) | 96.0 ± 2.6 | 85.5 ± 4.7 | 0.09 |

| P* | 0.22 | 0.07 | |

| Baseline BMI (Kg/M2) | 33.8 + 1.3 | 31.9 + 1.7 | 0.43 |

| Post-Intervention BMI (Kg/M2) | 34.1 ± 1.4 | 32.3 ± 1.8 | 0.46 |

| P* | 0.17 | 0.06 | |

| Baseline LBM (Kg) | 44.6 + 2.5 | 38.7 + 1.1 | 0.06 |

| Post-Intervention LBM (Kg) | 46.0 ± 2.4 | 38.6 ± 1.0 | 0.02 |

| P* | 0.05 | 0.89 | |

| Baseline FPG at −180min (mmol/l) | 5.86 ± 0.10 | 5.97 ± 0.23 | 0.70 |

| Post-Intervention FPG at −180min (mmol/l) | 5.95 ± 0.18 | 5.72 ± 0.09 | 0.23 |

| P* | 0.52 | 0.17 | |

| Baseline FPG at 0min (mmol/l) | 5.96 ± 0.10 | 5.79 ± 0.15 | 0.47 |

| Post-Intervention FPG at 0min (mmol/l) | 5.92 ± 0.14 | 5.81 ± 0.11 | 0.71 |

| P* | 0.75 | 0.91 | |

P value for unpaired, two-way t-test between treatment groups;

P value for paired, two-way t-test within a treatment group.

FPG = Fasting Plasma Glucose. BMI = Body Mass Index. LBM = Lean Body Mass

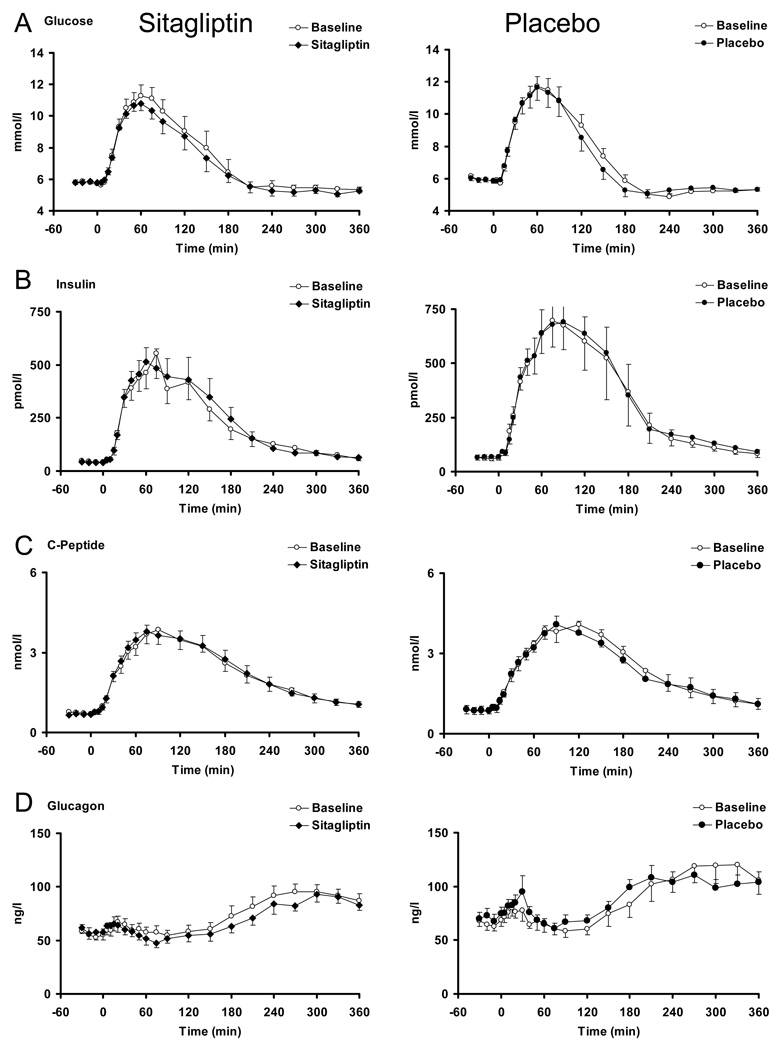

GLP-1 and GIP concentrations (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Intact GIP, Total GIP, Intact GLP-1 and Total GLP-1 in the presence (black squares = solid bars) and absence (white squares = open bars) of sitagliptin (left panels) and placebo (right panels).

After 8 weeks of sitagliptin treatment, fasting (5.7±1.6 vs. 8.6±1.6 pmol/l, p = 0.05) and postprandial (11.0±0.8 vs. 24.0±1.5 nmol per 6h, p < 0.01) intact GIP concentrations were increased. Interestingly, placebo treatment was associated with a slight, but significant, rise in fasting (3.1±0.9 vs. 6.7±1.7 pmol/l, p = 0.03) but not postprandial intact GIP concentrations (9.9±1.1 vs. 10.6±1.2 nmol per 6h, p = 0.29 - Panel A).

Sitagliptin lowered fasting (6.5±1.1 vs. 1.9±1.3 pmol/l, p = 0.003) and postprandial total GIP concentrations (22.3±2.4 vs. 16.5±1.2 nmol per 6h, p = 0.01) after 8 weeks of treatment whereas there was a trend to higher fasting (2.6±1.0 vs. 5.6±1.7 pmol/l, p = 0.02) and postprandial (20.1±2.6 vs. 21.7±2.8 nmol per 6h, p = 0.09) concentrations after treatment with placebo – (Panel B).

Sitagliptin treatment did not alter fasting (0.8±0.2 vs. 1.3±0.3 pmol/l, p = 0.15) but increased postprandial (814±130 vs. 1240±170 pmol per 6h, p = 0.003) intact GLP-1 concentrations. Placebo did not alter intact GLP-1 concentrations – (Panel C).

Sitagliptin decreased postprandial total GLP-1 concentrations (5652±357 vs. 5034±257 pmol per 6h, p = 0.02). Intriguingly, while total GLP-1 concentrations were unchanged (5008±428 vs. 5560±446 pmol per 6h, p = 0.11) by placebo – (Panel D), there was a suggestion of higher total GLP-1 concentrations 30 (20.6±2.3 vs. 29.9±7.0 pmol/l, p = 0.10) and 60 (14.7±1.5 vs. 19.1±2.8 pmol/l, p = 0.07) minutes after meal ingestion in the placebo group. Please also refer to supplementary table 2 for further details.

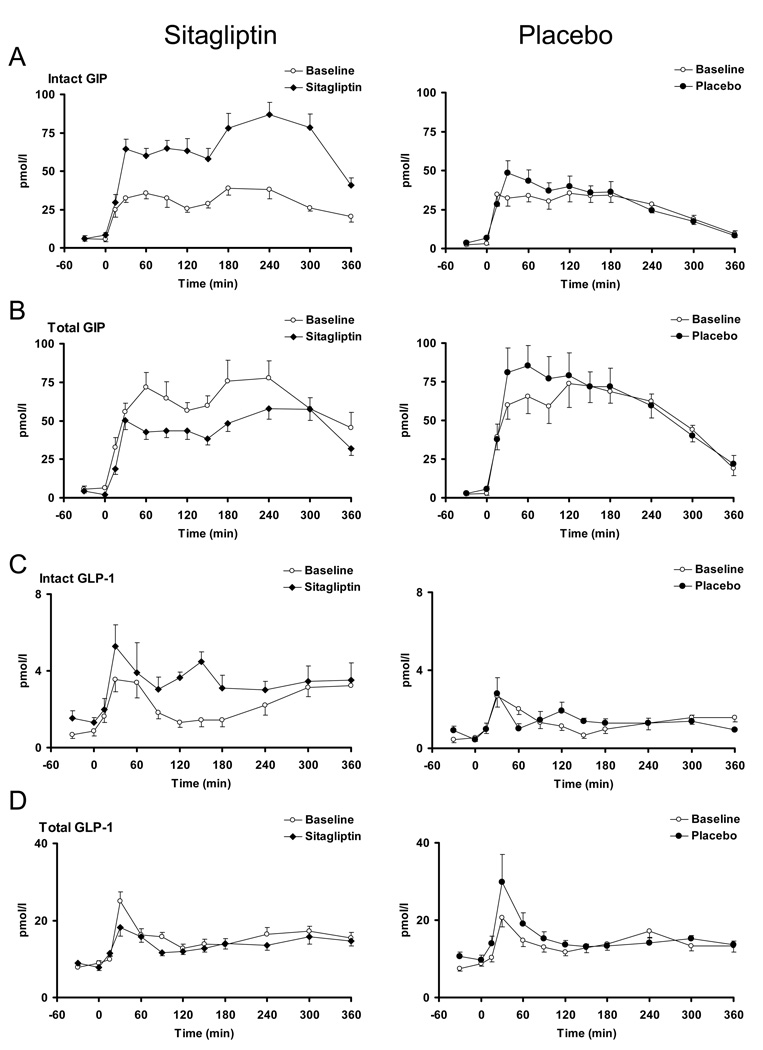

Plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide and glucagon concentrations (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Glucose, Insulin, C-Peptide and Glucagon concentrations in the presence (black squares = solid bars) and absence (white squares = open bars) of sitagliptin (left panels) and placebo (right panels).

Administration of sitagliptin (5.71±0.14 vs. 5.78±0.12 mmol/l, p = 0.60) or placebo (5.87±0.10 vs. 5.83±0.12 mmol/l, p = 0.68) did not alter fasting glucose prior to meal ingestion. Postprandial glucose concentrations were unchanged by sitagliptin (540±132 vs. 415±91 mmol per 6h, p = 0.09) and placebo (421±62 vs. 392±73 mmol per 6h, p = 0.28), (Panel A).

Baseline, peak or overall postprandial insulin (Panel B) or C-peptide (Panel C) concentrations did not differ after administration of sitagliptin or placebo.

Sitagliptin or placebo did not appreciably alter postprandial glucagon concentrations (Panel D). Fasting glucagon concentrations decreased minimally after sitagliptin administration (60.5±5.9 vs. 58.2±5.9 ng/l, p < 0.01) but not after placebo.

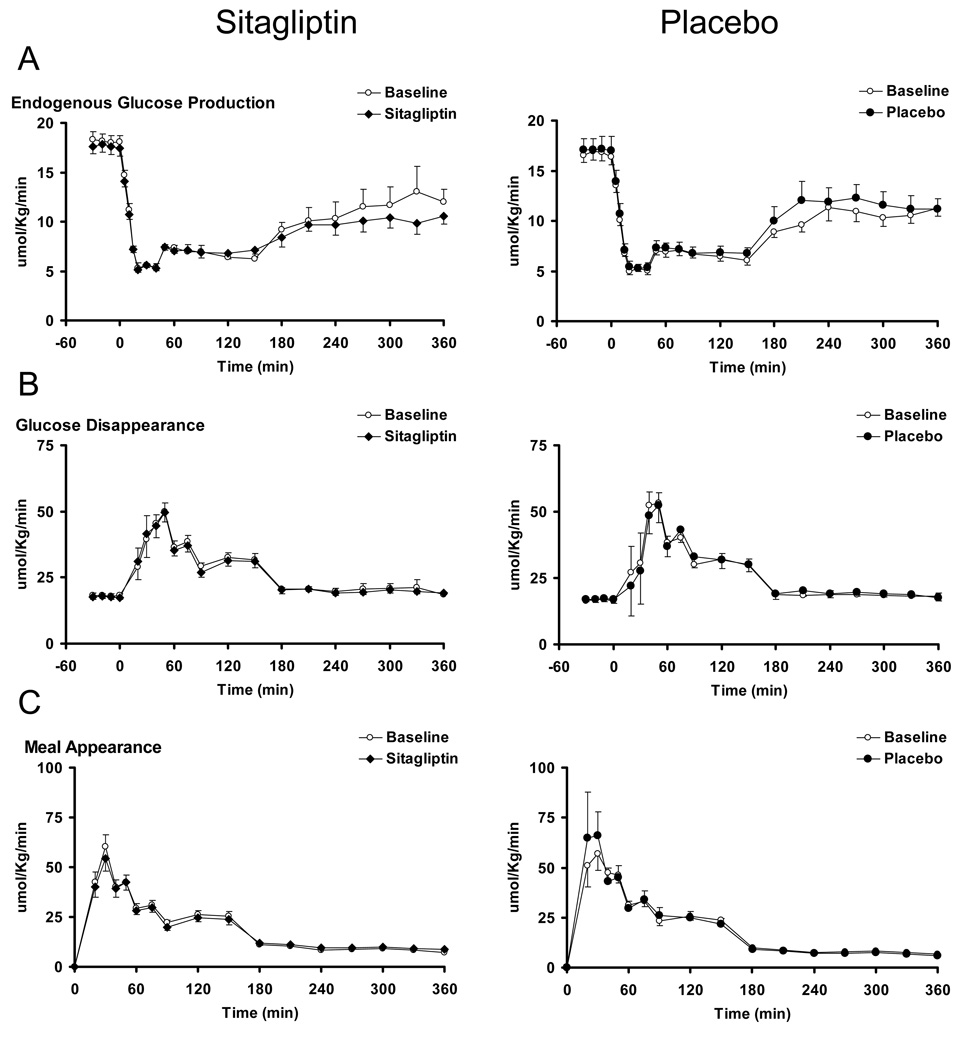

Endogenous Glucose Production, Glucose Disappearance and Meal Appearance (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Endogenous glucose production, glucose disappearance and meal appearance in the presence (black squares = solid bars) and absence (white squares = open bars) of sitagliptin (left panels) and placebo (right panels).

Fasting and postprandial suppression of endogenous glucose production was unchanged by treatment with sitagliptin as well as placebo (Panel A).

Peak and postprandial glucose disappearance did not differ from baseline after sitagliptin or placebo treatment (Panel B).

The appearance of ingested glucose did not differ from baseline after treatment with sitagliptin or placebo. (Panel C). Please also refer to supplementary table 3 for further details.

Insulin Action, Insulin secretion and Disposition Indices (Table 2)

Table 2.

Insulin Secretion and action before and after intervention

| Placebo | Sitagliptin | P# | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline ϕStatic (10−9 min−1) | 42.9 ± 4.4 | 46.9 ± 5.7 | 0.58 |

| Post-Intervention ϕStatic (10−9 min−1) | 45.7 ± 5.3 | 52.5 ± 5.7 | 0.39 |

| P* | 0.48 | 0.32 | |

| Baseline ϕDynamic (10−9) | 625 ± 92 | 680 ± 105 | 0.70 |

| Post-Intervention ϕDynamic (10−9) | 688 ± 164 | 694 ± 100 | 0.97 |

| P* | 0.68 | 0.90 | |

| Baseline ϕTotal (10−9 min−1) | 49.5 ± 5.1 | 61.3 ± 12.9 | 0.40 |

| Post-Intervention ϕTotal (10−9 min−1) | 52.4 ± 5.4 | 62.6 ± 8.5 | 0.33 |

| P* | 0.51 | 0.93 | |

| Baseline SI (10−4 dl/kg/min per µU/ml) | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 0.13 |

| Post-Intervention SI (10−4 dl/kg/min per µU/ml) | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 0.09 |

| P* | 0.92 | 0.31 | |

| Baseline DIStatic (10−14 dl/kg/min2 per pmol/l) | 92.0 ± 18.5 | 134 ± 22.8 | 0.16 |

| Post-Intervention DIStatic (10−14 dl/kg/min2 per pmol/l) | 104.5 ± 22.0 | 191.3 ± 41.4 | 0.08 |

| P* | 0.34 | 0.04 | |

| Baseline DIDynamic (10−14 dl/kg/min per pmol/l) | 1233 ± 245 | 1893 ± 386 | 0.16 |

| ntervention DIDynamic (10−14 dl/kg/min per pmol/l) | 1475 ± 446 | 2287 ± 484 | 0.23 |

| P* | 0.57 | 0.38 | |

| Baseline DITotal (10−14 dl/kg/min2 per pmol/l) | 107 ± 22 | 161 ± 26 | 0.12 |

| Post-Intervention DITotal (10−14 dl/kg/min2 per pmol/l) | 120 ± 24 | 228 ± 53 | 0.08 |

| P* | 0.20 | 0.08& | |

P value for unpaired, two-way t-test between treatment groups;

P value for paired, two-way t-test within a treatment group;

P value for paired, one-way test = 0.04.

Sitagliptin did not alter net insulin action (SI) or secretion (ϕtotal). DItotal demonstrated a slight increase after 8 weeks treatment with sitagliptin. DIstatic but not DIDynamic, was increased by sitagliptin.

Discussion

The present studies indicate that use of DPP-4 inhibition to raise circulating concentrations of intact GLP-1 and GIP did not lower fasting or postprandial glucose concentrations in IFG. This would imply that circulating incretin concentrations play no role in the pathogenesis of IFG. While DPP-4 inhibition resulted in a slight improvement in β-cell function (as manifest by a slightly increased Disposition Index), this was not sufficient to alter endogenous glucose production, meal appearance or glucose uptake.

These observations differ from previous observations in type 2 diabetes where DPP-4 inhibitors lower fasting and postprandial glucose concentrations [18] due to enhanced insulin secretion and suppression of glucagon secretion [8], and perhaps by an effect on insulin action [19]. A potential explanation is that incretins are less potent stimulators of insulin secretion in IFG. While there is limited data in IFG [9], incretins stimulate insulin secretion in IGT [10]. Both prior published studies examining the effect of DPP-4 inhibition in IFG / IGT, like the present study, reported no effect on fasting glucose concentrations.

A second explanation is that DPP-4 inhibition does not raise incretin hormones sufficiently. However, the magnitude by which the fasting and postprandial concentrations of intact hormone are increased by DPP-4 inhibition are similar to those observed in diabetes. It has been suggested that increased intact GLP-1 produces negative-feedback inhibition of the L cell [20]. A single dose of sitagliptin in people with type 2 diabetes resulted in decreased total GIP and GLP-1 concentrations [21]. In this study, DPP-4 inhibition decreased total GLP-1 and GIP concentrations suggesting an inhibitory effect on the L and K cells respectively. It is unknown if the effect of sustained DPP-4 inhibition on enteroendocrine secretion differs in type 2 diabetes and IFG.

A third explanation is that the minimal incretin-induced increase in insulin secretion could not overcome the defect in insulin action. We favor this view since DI is modestly increased and since we and others have shown that insulin resistance decreases postprandial glucose uptake and is primarily the cause of postprandial hyperglycemia [2, 22]and elevated fasting glucose concentrations [2, 23]. DPP-4 inhibition did not increase fasting insulin secretion. It is interesting to speculate that the limited ability of DPP-4 inhibitors to increase insulin secretion in IFG may be due to the fact that incretin induced insulin secretion is glucose dependent, and glucose concentrations are only modestly elevated in IFG. This would be compatible with the absence of effect of DPP-4 inhibition on insulin secretion and glucose concentrations in healthy humans [24]. Glucose dose-response studies to examine incretin-induced insulin secretion in IFG will be required to determine if the effects of DPP-4 inhibition in prediabetes are dependent on the prevailing glucose concentrations. This explanation may also explain the differing effectiveness of DPP-4 inhibition on postprandial glucose concentrations in this study compared to other studies in glucose-intolerant subjects with higher postprandial glucose concentrations [9, 10].

Glucagon concentrations are variable in IFG or IGT [4, 25]. In previous studies we noted that fasting glucagon concentration did not differ in IFG and NFG (normal fasting glucose) but postprandial suppression was impaired in IFG [2]. Since we did not include a control group with NFG and normal glucose tolerance in the present studies, we cannot determine if regulation of glucagon concentrations was abnormal in the present subjects. DPP-4 inhibition lowered fasting glucagon concentrations but did not alter postprandial suppression. On the other hand, DPP-4 inhibition increased both fasting and postprandial GLP-1 concentrations. The increased fasting GLP-1 concentration may have suppressed fasting glucagon concentrations but postprandial GLP-1 concentrations may have been insufficiently high to counteract the stimulatory effect of the meal protein. The previously published studies of DPP-4 inhibition in prediabetes did not report a consistent effect on glucagon concentrations [9, 10]. Of note the postprandial pattern of change of insulin and C-peptide concentrations were virtually identical before and after treatment indicating that increased circulating incretin concentrations had no effect on hepatic insulin clearance

In summary, this study demonstrates that short-term DPP-4 inhibition in IFG does not alter glucose concentrations and glucose metabolism. This would suggest that incretin hormones play little role in the pathogenesis of IFG. In addition to raising concentrations of GLP-1 and GIP by inhibiting DPP-4 mediated degradation, sitagliptin lowered total GLP-1 and GIP suggesting negative feedback inhibition of enteroendocrine secretion. Whether this alters the magnitude of response and whether this also occurs after extended treatment in type 2 diabetes remains unknown. It also remains to be determined whether longer periods of DPP-4 inhibition in people with IFG measurably alter β-cell function, fasting and postprandial glucose concentrations in a way that is sustained even after treatment discontinuation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments / Disclosure

Grant Support: We thank Merck Pharmaceuticals for providing sitagliptin and matched placebo. The authors acknowledge the support of the Mayo Clinic General Clinical Research Center. Dr. Vella and Dr. Cobelli are supported by DK78646, Dr. Basu and Dr. Rizza by DK29953.

AV has received research grants from Merck and has consulted for Sanofi-Aventis and Daiichi-Sankyo. RAR is a member of the advisory boards of Merck, Novo Nordisk, Takeda, Mankind and Eli Lilly and a consultant for Abbott and Eli Lilly. CFD has received lecture fees from Merck, Novartis and Novo Nordisk; CFD’s spouse is employed by Merck and holds stock in Merck and Novo Nordisk. JJH has consulted for Merck, and has received lecture fees from Merck, Novartis and research grants from both Merck and Novartis

References

- 1.Tirosh A, Shai I, Tekes-Manova D, Israeli E, Pereg D, Shochat T, et al. Normal fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes in young men. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 6;353(14):1454–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock G, Dalla Man C, Campioni M, Chittilapilly E, Basu R, Toffolo G, et al. Pathogenesis of pre-diabetes: mechanisms of fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia in people with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2006 Dec;55(12):3536–3549. doi: 10.2337/db06-0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rask E, Olsson T, Soderberg S, Holst Jj J, Tura A, Pacini G, et al. Insulin secretion and incretin hormones after oral glucose in non-obese subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Metabolism. 2004 May;53(5):624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toft-Nielsen MB, Damholt MB, Madsbad S, Hilsted LM, Hughes TE, Michelsen BK, et al. Determinants of the impaired secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001 Aug;86(8):3717–3723. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laakso M, Zilinskaite J, Hansen T, Boesgaard TW, Vanttinen M, Stancakova A, et al. Insulin sensitivity, insulin release and glucagon-like peptide-1 levels in persons with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance in the EUGENE2 study. Diabetologia. 2008 Mar;51(3):502–511. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0899-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritsche A, Stefan N, Hardt E, Haring H, Stumvoll M. Characterisation of beta-cell dysfunction of impaired glucose tolerance: evidence for impairment of incretin-induced insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2000 Jul;43(7):852–858. doi: 10.1007/s001250051461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006 Nov 11;368(9548):1696–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalla Man C, Bock G, Giesler PD, Serra DB, Ligueros Saylan M, Foley JE, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition by vildagliptin and the effect on insulin secretion and action in response to meal ingestion in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009 Jan;32(1):14–18. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utzschneider KM, Tong J, Montgomery B, Udayasankar J, Gerchman F, Marcovina SM, et al. The dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor vildagliptin improves beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. Diabetes Care. 2008 Jan;31(1):108–113. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenstock J, Foley JE, Rendell M, Landin-Olsson M, Holst JJ, Deacon CF, et al. Effects of the dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor vildagliptin on incretin hormones, islet function, and postprandial glycemia in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2008 Jan;31(1):30–35. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orskov C, Rabenhoj L, Wettergren A, Kofod H, Holst JJ. Tissue and plasma concentrations of amidated and glycine-extended glucagon-like peptide I in humans. Diabetes. 1994 Apr;43(4):535–539. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vilsboll T, Agerso H, Krarup T, Holst JJ. Similar elimination rates of glucagon-like peptide-1 in obese type 2 diabetic patients and healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Jan;88(1):220–224. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beylot M, Previs SF, David F, Brunengraber H. Determination of the 13C-labeling pattern of glucose by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1993 Aug 1;212(2):526–531. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steele R, Bjerknes C, Rathgeb I, Altszuler N. Glucose uptake and production during the oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes. 1968 Jul;17(7):415–421. doi: 10.2337/diab.17.7.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalla Man C, Caumo A, Basu R, Rizza R, Toffolo G, Cobelli C. Measurement of selective effect of insulin on glucose disposal from labeled glucose oral test minimal model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Nov;289(5):E909–E914. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00299.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breda E, Cavaghan MK, Toffolo G, Polonsky KS, Cobelli C. Oral glucose tolerance test minimal model indexes of beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2001 Jan;50(1):150–158. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Cauter E, Mestrez F, Sturis J, Polonsky KS. Estimation of insulin secretion rates from C-peptide levels. Comparison of individual and standard kinetic parameters for C-peptide clearance. Diabetes. 1992 Mar;41(3):368–377. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vella A, Bock G, Giesler PD, Burton DB, Serra DB, Saylan ML, et al. Effects of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibition on Gastrointestinal Function, Meal Appearance, and Glucose Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2007 May;56(5):1475–1480. doi: 10.2337/db07-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azuma K, Radikova Z, Mancino J, Toledo FG, Thomas E, Kangani C, et al. Measurements of islet function and glucose metabolism with the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor vildagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Feb;93(2):459–464. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deacon CF, Wamberg S, Bie P, Hughes TE, Holst JJ. Preservation of active incretin hormones by inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV suppresses meal-induced incretin secretion in dogs. J Endocrinol. 2002 Feb;172(2):355–362. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1720355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herman GA, Bergman A, Stevens C, Kotey P, Yi B, Zhao P, et al. Effect of single oral doses of sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, on incretin and plasma glucose levels after an oral glucose tolerance test in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Nov;91(11):4612–4619. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weyer C, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Metabolic characteristics of individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 1999 Nov;48(11):2197–2203. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.11.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bock G, Dalla Man C, Campioni M, Chittilapilly E, Basu R, Toffolo G, et al. Effects of nonglucose nutrients on insulin secretion and action in people with pre-diabetes. Diabetes. 2007 Apr;56(4):1113–1119. doi: 10.2337/db06-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman GA, Stevens C, Van Dyck K, Bergman A, Yi B, De Smet M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of sitagliptin, an inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase IV, in healthy subjects: results from two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies with single oral doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Dec;78(6):675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henkel E, Menschikowski M, Koehler C, Leonhardt W, Hanefeld M. Impact of glucagon response on postprandial hyperglycemia in men with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2005 Sep;54(9):1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]