Abstract

In an effort to advance an understanding of the phenomenology of bipolar II depression, the current study used methods based in item response theory to evaluate differences in DSM-IV depression symptom endorsement in an epidemiological sample of individuals with a history of hypomania (i.e., bipolar II depression) in comparison to: a) individuals with a history of mania (i.e., bipolar I depression), and b) individuals without a history of hypomania or mania (i.e., unipolar depression). Clinical interview data were drawn from a subsample (n = 13,753) of individuals with bipolar II, bipolar I, or unipolar depression who had participated in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. A two-parameter item response model was used to estimate differential item functioning (DIF) between these groups. Differences in severity parameter estimates revealed that suicidal ideation/attempt was less likely to be endorsed across most levels of depression severity in bipolar II versus bipolar I disorder. There were no significant differences between groups on the remaining DSM-IV symptoms. Although preliminary, current study data are consistent with recent assertions that depression may be understood as a clinical phenomenon that is consistent across the major affective disorders. An exception to this conclusion may be in the area of suicidal ideation, which requires additional attention.

Keywords: bipolar II depression, bipolar I depression, unipolar depression, item response theory

1. Introduction

Although typically considered a more mild form of bipolar illness, emerging data indicate that bipolar II disorder (BP II) is associated with frequent and debilitating depressive episodes that largely account for the significant morbidity and mortality associated with the disorder (Judd et al., 2003). Given such a depression-predominant course of illness, clinicians must often rely on retrospective reports of hypomanic episodes to inform diagnostic decisions. Not surprisingly, initial misdiagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD) is most common (Hirschfeld et al., 2003). Yet even when MDD is ruled out, it may still be difficult to discern between BP II and bipolar I disorder (BP I) when patients present with depressive symptoms.

Indeed, the literature is mixed as to whether there are specific symptoms of depression that can be used to differentiate BPII from its BPI and unipolar counterparts. Some (Akiskal & Benazzi, 2005; Hantouche & Akiskal, 2005; Perugi et al., 1998), but not all (Parker et al., 2000; Robertson et al., 1996), have reported a greater prevalence of atypical symptoms in BP II relative to MDD. Others have reported greater rates of anxious and agitated depression (Vieta & Suppes, 2008; MacQueen & Young, 2001) in BP II versus MDD. Even less is known about whether there are distinct features of depression that differentiate BP II and BP I. A literature search revealed only one relevant study, which reported a greater prevalence of atypical depressive symptoms in BP II vs. BP I, and a greater prevalence of psychosis in BP I (Brugue et al., 2008). Yet in contrast to an emphasis on differences across disorders, a recent review concluded that bipolar and unipolar depression are more similar than different (Cuellar et al., 2005), and others have recently argued that depression cannot be differentiated across bipolar and unipolar mood disorders (Joffe et al., 1999).

The majority of research comparing bipolar II depression to either unipolar or bipolar I depression has been limited in that it has targeted atypical or other features specifiers and has not addressed potential differences across all of the DSM-IV depressive symptoms (Akiskal & Benazzi, 2005; Brugue et al., 2008; Hantouche & Akiskal, 2005; Parker et al., 2000; Perugi et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 1996). Research in this area has also been limited by the use of relatively small clinic-based (vs. epidemiological) samples (Akiskal & Benazzi, 2005; Brugue et al., 2008; Parker et al., 2000; Perugi et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 1996), lack of statistical correction for multiple comparisons (cf., Cuellar et al., 2005), and a failure of control for overall depression symptom severity between groups (Brugue et al., 2008; Parker et al., 2000; Perugi et al., 1998; Robertson et al., 1996). This last point is critical because it is unclear whether any differential symptom expression reported in the literature is due to true phenomenological differences between BP II and its BP I and MDD counterparts, or whether such differences are reflective of greater overall symptom severity in one group versus another.

To further characterize the phenomenology of bipolar II depression, the current study used methods based in Item Response Theory (IRT) (Lord, 1980) to evaluate differences in the likelihood of DSM-IV major depression symptom endorsement among individuals with a history of hypomania (i.e., bipolar II depression) in comparison to individuals with a history of mania (i.e., bipolar I depression) and individuals without a history of hypomania or mania (i.e., unipolar depression). Given that the specific aim of current study analyses was to clarify depression symptom expression in BP II, we did not directly compare bipolar I and unipolar depression. Interested readers are referred to Weinstock et al. (2009) for this analysis. Advantages of using an IRT-based approach over other statistical methodologies is that it allows one to examine the likelihood that a particular symptom will be endorsed at a particular level of depression severity. Thus, differences in symptom endorsement between groups can be evaluated while simultaneously equating for individual levels of depression symptom severity. Further extending this literature, we conducted analyses using a large, epidemiological sample of individuals.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were drawn from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (Grant et al., 2003a), a NIAAA-funded survey of adults in the United States aged 18 years or older. To date, the NESARC represents the largest epidemiological survey of psychiatric conditions in the United States. Methods for obtaining the sample have been detailed elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004). In brief, informed consent was obtained from all participants. Only those respondents who reported lifetime depressed mood or anhedonia completed the section of the NESARC assessing lifetime occurrence of all DSM-IV symptoms of a major depressive episode (MDE). Of the 43,093 adults surveyed, 695 endorsed lifetime depressive symptoms and a lifetime history of hypomanic episodes (i.e., bipolar II depression), 1154 endorsed lifetime depressive symptoms and a lifetime history of manic episodes (i.e., bipolar I depression) and 11,904 endorsed lifetime depressive symptoms in the absence of hypomania or mania (i.e., unipolar depression). The present analysis consisted of only those individuals (N = 13,753; 32% of the total NESARC sample). For participants with bipolar II depression, average age was 36.2 (SD = 14.0), 60% (n = 414) were female, 74% (n = 516) were Caucasian, and 81% (n = 566) were of non-Hispanic ethnicity. Among participants with bipolar I depression, average age was 39.4 (SD = 14.8), 63% (n = 727) were female, 78% (n = 898) were Caucasian, and 83% (n = 958) were of non-Hispanic ethnicity. Among participants with unipolar depression, average age was 47.1 (SD = 17.2), 66% (n = 7,857) were female, 80% (n = 9,544) were Caucasian, and 84% (n = 9,999) were of non-Hispanic ethnicity.

2.2. Clinical Assessments

The Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities Schedule-DSM-IV version (AUDADIS-IV; Grant et al., 2001;Grant et al., 2003b) was used to assess hypomanic and manic episode criteria and MDE symptoms. NESARC estimates of lifetime and 12-month prevalence of illness for BP II were 1.1% and 0.8%, for BP I were 3.3% and 2.0%, and for MDD were 13.2% and 5.3%. These estimates are generally comparable to those found in other recent epidemiological surveys (Kessler et al., 2005b), although it should be noted that the prevalence rates for BP I in the NESARC “slightly exceeded the upper end of the range” of previously reported estimates (Grant et al., 2005; p. 1211). The slightly higher prevalence of BP I in the NESARC may also reflect a cohort effect for bipolar disorder that was identified in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, in which prevalence has been shown to be increasing over time (Kessler et al., 2005a; Parker et al., 2006).

For purposes of analysis, bipolar II depression was characterized by endorsement of lifetime MDE symptoms and of lifetime threshold-level hypomanic episode criteria. Bipolar I depression was characterized by endorsement of lifetime MDE symptoms and of lifetime threshold-level manic episode criteria. Unipolar depression was characterized by endorsement of lifetime MDE symptoms in the absence of any hypomanic or manic episodes. Analyses focused on the 7 MDE symptoms assessed by the AUDADIS-IV once depressed mood and/or anhedonia were endorsed: appetite/weight disturbance, sleep disturbance, psychomotor disturbance, fatigue, worthlessness/guilt, concentration difficulty, and suicidal ideation/attempt.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Overview

In order to estimate differential item functioning (DIF) in bipolar II versus bipolar I and unipolar depression, a 2-parameter item response model was used. Item response modeling allows us to examine the likelihood that a particular symptom will be reported at a particular level of depression severity (i.e., the latent trait) in different groups. One particular advantage of IRT is that it overcomes the assumption that total number of symptoms determines severity (e.g., endorsement of 2 symptoms is twice as severe as endorsement of 1 symptom), and instead focuses on the pattern of symptom endorsement, relying on a common metric (i.e., standard deviation units) to quantify underlying severity. As this method ensures that individual characteristics do not affect interpretation of total symptom counts, equal comparisons can be made across groups. The estimate of DIF involved comparing a series of analyses that isolate and compare each item parameter across each identified group (Camilli & Shepard, 1994; Holland & Wainer, 1993). If the symptoms function similarly across groups, then the parameters that describe the symptoms of depression will be estimated similarly in different samples.

2.3.2. IRT model

Parametric models begin with a specific model of how the relationship between the probability of an item response (i.e., endorsement of a particular depression symptom) and an individual’s level of the underlying trait (i.e., depression severity) should look (i.e., the item response function), and then models the estimated parameters that describe the relationship. The 2-parameter item response model estimates: 1) a severity parameter to describe the point on the continuum of the latent trait where a symptom becomes likely to be observed (e.g., > 50%) and 2) a discrimination parameter to describe how rapidly the probability of observing the symptom changes across increasing levels of the latent continuum (e.g., the slope of the item response function). In the current study, we were most interested in DIF that occurred in the severity parameter because it is reflective of the likelihood that a given symptom will occur at a given severity level. However, the discrimination parameter is important in that it can be used to identify, by group, whether a given symptom is a good or poor indicator of the underlying latent trait.

2.3.3. IRT Assumptions

The primary assumption of item response models is that responses to symptom endorsement is a function of individual variation along a single underlying dimension (i.e., depression severity), which we tested using confirmatory common factor analysis. This assumption is meaningful for both theoretical and statistical reasons. Theoretically, the DSM-IV stipulates that symptoms are summed to determine the presence or absence of a depression diagnosis. In so doing, DSM-IV assumes that responses are linked to a single construct of depression severity (Thurstone, 1928). Statistically, information regarding symptom functioning may be biased if a unidimensional item response model is applied to multidimensional data.

An additional IRT assumption is that symptoms be locally independent. That is, symptoms must not be correlated for reasons other than measurement of the latent trait (Lord, 1980). For the MDE symptoms that comprise appetite/weight disturbance, sleep disturbance, and psychomotor disturbance, one could reliably predict the absence of one symptom (e.g., insomnia) from the presence of the other (e.g., hypersomnia), irrespective of depressive severity. Thus, we can assume that the component parts of these symptoms are locally dependent and thus not appropriate for evaluation separately in an IRT analysis. To properly account for this assumption, the symptoms of appetite/weight disturbance, sleep disturbance, and psychomotor disturbance were therefore evaluated as compound items that directly parallel the larger DSM-IV criteria that are used in the assignment of MDE diagnosis. For descriptive purposes, frequencies of endorsement for each of the component parts of these symptoms are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial Symptom Parameters and Differential Item Functioning of DSM-IV MDE Symptoms for Bipolar II Depression (n = 695) in Comparison to those with Bipolar I (n = 1154) and Unipolar (n = 11,904) depression

| Bipolar II Depression (n = 695) |

Bipolar I Depression (n = 1154) |

Unipolar Depression (n = 11,904) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV MDE Symptoms | % | a | b | % | G2 (df = 2) | Severity DIF | Discrimination DIF | % | G2 (df = 2) | Severity DIF | Discrimination DIF |

| Depressed Mood | 90.2 | – | – | 92.8 | – | – | – | 93.1 | – | – | – |

| Anhedonia | 85.8 | – | – | 91.6 | – | – | – | 74.6 | – | – | – |

| Appetite/Weight Disturbance | 77.7 | 1.41 | -1.66 | 84.4 | 0.5 | -0.06 | 0.02 | 62.6 | 0.3 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Decreased Appetite/Weight Loss | 56.7 | – | – | 63.4 | – | – | – | 45.0 | – | – | – |

| Increased Appetite/Weight Gain | 33.7 | – | – | 44.0 | – | – | – | 25.4 | – | – | – |

| Sleep Disturbance | 86.0 | 2.30 | -1.76 | 91.2 | 0.5 | -0.02 | 0.11 | 71.2 | 5.6 | 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Insomnia | 70.5 | – | – | 79.6 | – | – | – | 58.9 | – | – | – |

| Hypersomnia | 45.0 | – | – | 52.0 | – | – | – | 31.1 | – | – | – |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | 67.5 | 1.71 | -1.13 | 79.1 | 1.2 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 45.2 | 4.1 | -0.14 | -0.13 |

| Psychomotor Agitation | 53.5 | – | – | 68.7 | – | – | – | 34.4 | – | – | – |

| Psychomotor Retardation | 41.3 | – | – | 47.3 | – | – | – | 24.5 | – | – | – |

| Fatigue | 74.1 | 1.75 | -1.39 | 80.4 | 5.4 | -0.03 | 0.37 | 59.3 | 9.3* | 0.14 | -0.17 |

| Worthlessness/Guilt | 72.1 | 1.57 | -1.33 | 84.0 | 3.7 | -0.03 | -0.47 | 51.0 | 3.6 | -0.14 | -0.40 |

| Concentration | 86.2 | 2.31 | -1.77 | 90.7 | 2.0 | -0.03 | 0.26 | 66.4 | 2.1 | -0.07 | 0.11 |

| Suicide | 55.1 | 1.16 | -0.75 | 72.0 | 9.6* | 0.39** | 0.17 | 39.4 | 0.6 | -0.06 | 0.00 |

Note. a = discrimination parameter estimate. b = severity parameter estimate. Differences between groups were evaluated using 1 df tests, and p-values for 1 df tests were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Parameters that a) represent a statistically significant difference between groups, and b) meet our critiera for clinical significance are underlined. Frequencies for the component parts of appetite/weight, sleep, and psychomotor disturbance are presented for descriptive purposes only. Due to assumptions of local independence required for IRT analysis, these component items were not evaluated separately.

p < .01.

p < .003.

2.3.4. Differential Item Functioning

We employed version 2.0 of IRTLRDIF (Thissen, 2001) to complete DIF analyses. IRTLRDIF automatically accommodates group differences with respect to the latent trait. IRTLRDIF sets the scale of item parameters using the population distribution for the reference group. With the reference group mean set to zero and standard deviation set to 1, the estimated focal group mean reflects a standardized difference from the reference group and the standard deviation reflects the ratio of the focal and reference group standard deviations (Thissen, 2001). With respect to the current study analyses, the focal group was comprised of individuals with bipolar II depression whereas the reference group was comprised of individuals with bipolar I or unipolar depression.

Following Thissen et al. (1993), we used a likelihood-ratio test statistic to provide a significance test for the null hypothesis that the item response parameters do not differ between the identified groups. Analyses proceeded by initially constraining both discrimination and severity parameter estimates to be equal for the two subgroups across all seven symptoms (Model A). For each of the seven symptoms, a model was then fit that constrains all of the remaining symptoms’ discrimination and severity parameters to be equal, but allows the estimates for one symptom to differ across the two groups (Model B). The difference in the log- likelihoods (ll) of Model A and Model B (G2 = -2(llModel A – llModel B)) provides an omnibus test (df = 2) of whether there is DIF for the discrimination and/or severity parameter for this symptom. If significant, follow-up tests can be conducted to identify whether DIF is present in discrimination or severity parameters by further constraining models.

Given that we conducted DIF analyses across multiple symptoms, it is important to account for risk of Type I error. Although Bonferroni correction has typically been used to do so, this strategy can be conservative and may result in reduced power to detect differences. As an alternative, we employed the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995), using methods described elsewhere (Thissen et al., 2002). For all DIF analyses, we set alpha at .05. We used the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to adjust p-values for all 1df tests.

Given the large sample size employed in the current study, relatively small differences between groups may emerge as statistically significant. A priori, we decided that a difference greater or equal to .25 in item severity or discrimination parameters would represent a clinically meaningful difference. As described by Steinberg and Thissen (2006), a difference of .25 can be interpreted as one quarter “standard unit difference between the values of the [underlying] trait necessary to have a 50% chance of responding positively in one group compared to another” (Steinberg & Thissen, 2006; pp. 405-406). This may be considered to be a small effect size (Cohen, 1988). For example, a DIF of .25 for a given item severity would mean that, depending on the values of the discrimination parameters as well as how close the actual group severity parameters are to 0, differences in total group proportions responding affirmatively to a given item could range from 2% to 8% (for discrimination parameters range from 0.50 to 2.00) (Steinberg & Thissen, 2006).

3. Results

3.1. Unidimensionality Assumption

Fit statistics for the unidimensional model were calculated separately the bipolar and unipolar subgroups. For the BP II sample, fit indices (X2 = 39.53, df = 13; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.054) indicated a reasonable fit to the data. Fit statistics for the BP I sample (X2 = 62.11, df = 13; CFI = 0.945; TLI = 0.953; RMSEA = 0.057) and unipolar sample (X2= 543.95, df = 13; CFI = 0.977; TLI = 0.978; RMSEA = 0.059) were also adequate. We determined that these fit statistics were sufficient to proceed with fitting IRT models.

3.2. Differential Item Functioning

Table 1 lists frequency of endorsement of each of the depression symptoms for each group, as well as discrimination and severity parameter estimates for those with BP II. As reflected in the pattern of raw symptom endorsement (see Table 1), there were overall depression severity differences such that mean depression severity was 0.56 standard deviation units higher in BP I versus BP II, and that mean depression severity was 0.63 standard deviation units higher in BP II versus the unipolar group. These findings underscore the importance of using IRT DIF analyses that account for these overall differences in depression severity.

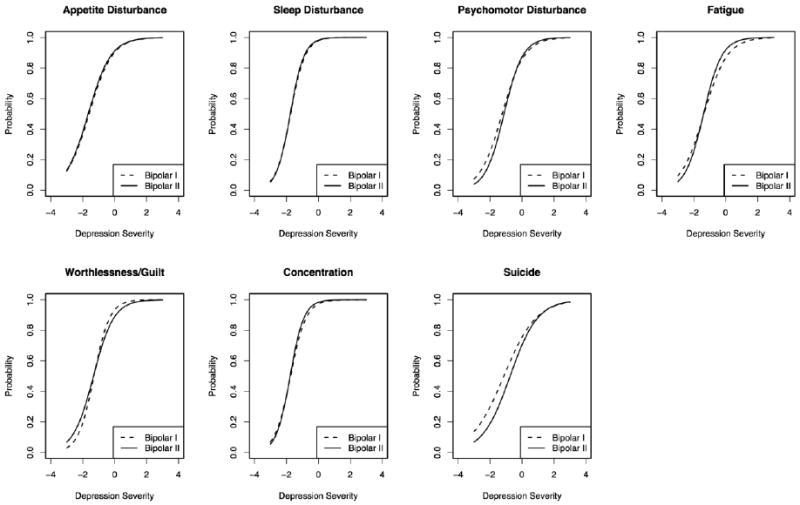

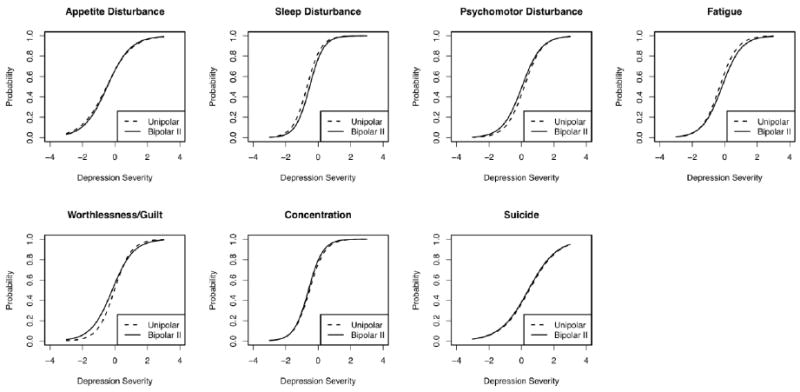

Table 1 also lists group differences in severity and discrimination parameter estimates for each symptom. Figures 1 and 2 represent pictorial representations of DIF analyses. As evidenced in Table 1, only one item exceeded study criteria for statistically and clinically significant severity DIF. Differences in severity parameter estimates for bipolar II and bipolar I depression revealed that suicidal ideation was endorsed at lower levels of severity, and thus more frequently, in bipolar I versus bipolar II depression (bbipolar II = -0.75, bbipolar I = -1.14, bdifference = 0.39). This difference was statistically significant (G2 = 9.1, df = 1, p < 0.003). Severity and discrimination DIF for BP II and BP I on all remaining symptoms was not significant. There was no significant severity or discrimination DIF between bipolar II and unipolar depression.

Figure 1.

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) between bipolar II and bipolar I depression for DSM-IV MDE symptoms.

Figure 2.

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) between bipolar II and unipolar depression for DSM-IV MDE symptoms.

4. Discussion

Results from the current study revealed that depression symptom expression in BP II was remarkably similar to that in BP I and unipolar depression. A visual inspection of the item response functions (see Fig 1 & 2) indicated that, with the exception of suicidal ideation in BP I, symptom expression was virtually identical in the three conditions. Although additional research is necessary to confirm such a conclusion, it is notable that these data are in keeping with recent arguments (Cuellar et al., 2005; Joffe et al., 1999; Swann, 1994) that depression may be understood as a clinical phenomenon that is relatively consistent across mood disorders. For example, using IRT methodology, our research group previously reported very few differences between BP I and unipolar depression, and the differences that did emerge fell into the small-to-medium effect size range (Weinstock et al., 2009). Nevertheless, as suggested by Brugue et al. (2008), it is also important to note that there may be clinical features that differentiate BP II from BP I and unipolar depression that are otherwise not DSM-IV symptoms of depression (e.g., anxiety) or that were not assessed in the NESARC (e.g., mood reactivity).

Indeed, there is a growing body of literature focused on atypicality of depression in BP II (Akiskal & Benazzi, 2005), and it is important to note that current study cannot be generalized to form conclusions about depressive subtypes. To the extent that we did have data on atypical symptoms (i.e., hypersomnia and hyperphagia), we could not evaluate these symptoms separately from their counterparts (i.e., insomnia and loss of appetite) due to the assumption of local independence described in the Methods. Of note, however, is that frequency of endorsement of the component parts of these items (see Table 1) reveals highest rates of atypical symptom endorsement in BPI and not BPII. Although these endorsement rates are unadjusted, they nevertheless provide some preliminary descriptive data that can be used to inform future research on depressive features specifiers across the mood disorders. Such research will be necessary in order to fully characterize any differential phenomenology of depression in BP II.

As noted above, current study analysis revealed a significant difference between BP II and BP I in the endorsement of suicidal ideation/attempt. The direction of this effect suggested that individuals with bipolar I depression were more likely to experience suicidal ideation at lower levels of depression severity, and thus more frequently than those with bipolar II depression. This finding runs counter to recent arguments that suicidal ideation and behaviors occur more frequently in bipolar II depression (Rihmer & Pestality, 1999). Also counter to the argument that suicide risk may be greatest in BP II, there were no significant differences in suicidal ideation/attempt between bipolar II and unipolar depression, and our prior IRT research evaluating bipolar I versus unipolar depression revealed greater likelihood of endorsement of suicidal ideation among those with BPI (Weinstock et al., 2009). Taken together, this pattern of findings suggests that the likelihood of endorsing suicidal ideation/attempt may actually be highest in bipolar I relative to bipolar II and unipolar depression, and no different between bipolar II and unipolar depression.

One possible explanation for this discrepancy from the published literature is that IRT analysis adjusts for overall depression severity, whereas most prior research comparing mood disorders has not (cf., Rihmer & Pestality, 1999). It is also important to note that mixed data concerning suicidality across the mood disorders may be related to how suicidal ideation and behaviors are measured in the extant literature (MacQueen & Young, 2001; Valtonen et al., 2009). Nevertheless, a visual inspection of the item response functions suggested that, at an average level of depression severity (i.e., latent trait = 0), the probability of endorsing suicidal ideation was approximately 76% for individuals with bipolar I depression in comparison to approximately 70% for individuals with bipolar II depression (see Fig. 1). Although we set a minimum effect size threshold for interpretation of clinical significance in the current study, it is notable that the effect size for the difference in suicidal ideation/attempt between BPII and BPI fell into the small effect size range. Such a subtle difference may not directly guide clinical decision making in applied settings (e.g., differential diagnosis), yet it is nevertheless important from a public health and empirical perspective. Perhaps most striking are the high rates of suicidal ideation endorsement in both groups, which clearly warrant continued clinical and empirical attention.

When interpreting the findings above, it is important to acknowledge study limitations. First, in order to be included in the data analysis, individuals must have endorsed either depressed mood or anhedonia. In the NESARC, the remaining DSM-IV depression symptoms were not assessed if one or both of these symptoms had not been endorsed. Thus, given that all of the current study sample endorsed either depressed mood or anhedonia, and most endorsed both, it would not be terribly meaningful, from a statistical perspective, to conduct DIF analyses on these items. It is also important to acknowledge that current study analyses did not account for clinical course characteristics (e.g., length of illness, rates of depressive or (hypo)manic episode recurrence or hospitalization, or medication regimen) that might have potentially influenced symptom profiles. Indeed, the data used in this study were cross-sectional, allowing for the evaluation of endorsement patterns of lifetime depressive symptoms only. Future research will be necessary in order to evaluate differences in depression symptom expression across mood disorders over longitudinal course of illness. Finally, it is important to reiterate that current study analyses cannot be used to form conclusions regarding depressive subtypes, nor can these data be used to form conclusions regarding bipolar mixed states, when individuals present with concurrent depression and (hypo)mania.

In conclusion, by addressing several limitations of the existing research, and employing a methodology grounded in Item Response Theory, current study results add to a small, yet growing literature focused on the phenomenology of bipolar II depression. Consistent with some recent assertions (Cuellar et al., 2005; Joffe et al., 1999; Swann, 1994), data suggested that DSM-IV depression symptom expression in BP II was very similar to that in BP I and unipolar depression. Although the frequency of suicidal ideation/attempt was higher in BP I relative to BP II, it should be noted that the effect size for this difference was small and that rates of endorsement in both groups were quite high and deserve continued clinical and empirical attention. Future research that continues to explore depression features specifiers in BP II remains an important area of inquiry; however, it is imperative that this research account for underlying depression severity when evaluating the distinct versus shared characteristics of BP II relative to its BP I and unipolar counterparts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akiskal HS, Benazzi F. Atypical depression: a variant of bipolar II or a bridge between unipolar and bipolar II? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;84:209–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Brugue E, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, Cruz N, Vieta E. Depression subtypes in bipolar I and II disorders. Psychopathology. 2008;41:111–114. doi: 10.1159/000112026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilli G, Shepard LA. Methods for Identifying Biased Test Items. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar AK, Johnson SL, Winters R. Distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:307–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B, Kaplan K, Shepard J, Moore T. Source and Accuracy Statement for Wave 1 of the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003a. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Difficulties Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003b;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12- month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:361–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:1205–15. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantouche EG, Akiskal HS. Bipolar II vs. unipolar depression: psychopathologic differentiation by dimensional measures. Journal of Affective Disorders. 84:127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld RM, Lewis L, Vornik LA. Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:161–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW, Wainer H. Differential Item Functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe RT, Young LT, MacQueen GM. A two-illness model of bipolar disorder 1. Bipolar Disorders. 1999;1:25–30. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.1999.10107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:261–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005a;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord F. Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen GM, Young LT. Bipolar II disorder: Symptoms, course, and response to treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:358–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Brotchie H, Fletcher K. An increased proportional representation of bipolar disorder in younger depressed patients: analysis of two clinical databases. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;95:141–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Roy K, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. The nature of bipolar depression: implications for the definition of melancholia. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;59:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Lattanzi L, Cecconi D, Mastrocinque C, Patronelli A, et al. The high prevalence of “soft” bipolar (II) features in atypical depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998;39:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihmer Z, Pestality P. Bipolar II disorder and suicidal behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1999;22:667–73. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HA, Lam RW, Stewart JN, Yatham LN, Tam EM, Zis AP. Atypical depressive symptoms and clusters in unipolar and bipolar depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1996;94:421–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Thissen D. Using effect sizes for research reporting: examples using item response theory to analyze differential item functioning. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:402–15. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC. Is bipolar depression a specific biological entity? In: Young LT, Joffe RT, editors. Bipolar Disorder: Biological Models and their Clinical Application. New York: Dekker; 1994. pp. 225–86. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D. IRTLRDIF v.2.0b: Software for the Computation of the Statistics Involved in Item Response Theory Likelihood-Ratio Tests for Differential Item Functioning. 2001 www.unc.edu/~dthissen/dl.html.

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Kuang D. Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2002;27:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Wainer H. Detection of differential item functioning using the parameters of item response models. In: Holland PW, Wainer H, editors. Differential Item Functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. pp. 67–113. [Google Scholar]

- Thurstone LL. Attitudes can be measured. American Journal of Sociology. 1928;33:529–54. [Google Scholar]

- Valtonen HM, Suominen K, Sokero P, Mantere O, Avilommi P, Leppamaki S, et al. How suicidal bipolar patients are depends on how suicidal ideation is defined. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Colom F, Martinez-Aran A, Benabarre A, Reinares M, Gasto C. Bipolar II disorder and comorbidity. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41:339–43. doi: 10.1053/comp.2000.9011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Suppes T. Bipolar II disorder: arguments for and against a distinct diagnostic entity. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10:163–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock LM, Strong D, Uebelacker LA, Miller IW. Differential item functioning of DSM-IV depressive symptoms in individuals with a history of mania versus those without: an item response theory analysis. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:289–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]