Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the Western world. Screening and detection of its precursor lesion, the adenoma could prevent development of colorectal cancer. Many studies have been done to evaluate the prevalence of colorectal cancer in different countries. In daily practice, it was noticed that colorectal cancer was rarely seen in patients of Turkish decent.

Aim

To evaluate the prevalence of colorectal cancer and adenoma in patients living in the Zaanstreek region, the Netherlands, and correlate these findings with ethnicity.

Materials and methods

All patients undergoing endoscopy of the colon and rectum during a period of 16 consecutive years in whom colorectal cancer and/or a polyp were diagnosed, were included in this study. All available histological data were retrieved in order to confirm the endoscopic diagnosis.

Results

In the study period, 907 patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Of these 13 (1.4%) were of Turkish descent (10 men and 3 women). The remaining 894 were authentic Dutch (473 men and 421 women). A total of 2,744 patients had one or more polyp(s) during endoscopy. There were 2,705 authentic Dutch (1,386 men, 1,319 women) and 39 Turkish patients (25 men, 14 women). There was no significant difference in gender in either of the groups.

Conclusion

Colorectal cancer and colonic adenoma are rare in patients of Turkish descent living in the Zaanstreek region, the Netherlands.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Adenoma, Turkish, Colonoscopy, Epidemiology

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies in the Western world. It is one of the diseases that has a well-known precursor lesion, namely the adenoma. Removal of adenomas ultimately could prevent development of colorectal cancer. For this reason, screening with faecal occult blood testing or colonoscopy in asymptomatic individuals above the age of 50 years is advocated in many countries.

Data are available on the prevalence of colorectal cancer in many countries (Rim et al. 2009; Weir et al. 2003; Ries et al. 2000; Siesling et al. 2008; Stirbu et al. 2006). Some recent papers reported on the prevalence of the disease in patients of different race and ethnicity (Chu et al. 1995; Siegel et al. 2008; Mahoney et al. 2009; Le et al. 2009). In a previous study in the Zaanstreek region in the Netherlands, it was already noted that diverticulosis of the colon is very rare in people of Turkish descent (Loffeld 2005). Also, reflux oesophagitis is rare in these individuals (Loffeld and van der Putten 2004). Hence, there appears to be a difference in morbidity patterns.

In daily practice it was noticed that colorectal cancer is rarely seen in patients of Turkish descent.

For this reason, a study was done in order to evaluate the prevalence of colorectal cancer and its precursor lesion, the adenoma, in the Zaanstreek and correlate the findings with Turkish ethnicity.

Materials and methods

All consecutive patients undergoing endoscopy of the colon and rectum in a period of 16 years (1992–2006) at the Endoscopy Department of the Zaans Medical Centre, the community hospital of the Zaanstreek region, the Netherlands were studied.

All endoscopies, the absolute majority being colonoscopies (Loffeld and van der Putten 2005), were done with Olympus endoscopes (EVIS 100, EXERA 160 and 180). Colon cleansing was done with Dulcolax®, Prunacolon® and enema or cleansing with PEG solution via nasogastric tube, in the beginning of the 1990s. Since 1995 this was done ambulatory with a commercial PEG solution (Klean prep® and Moviprep®).

All patients, undergoing an endoscopy, in whom a colorectal cancer and/or colon polyp(s) were diagnosed, were included in the present study. All available histology reports were retrieved in order to assess the histological characteristics of the polyps and to confirm the endoscopic diagnosis of cancer.

The patients were divided in two groups: group 1 all patients of Turkish descent, and group 2 all authentic Dutch patients. Patients of Turkish descent were identified via the specific, and well-known, Turkish family names.

A control group was defined as patients in whom endoscopy did not reveal abnormalities.

Statistical analysis was done with Chi-square test for contingency tables and t-test. A value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The Zaanstreek region has a population of approximately 132,500. According to the population registry 10–11% of these are immigrants from Turkey (first, second and third generation). These people originate mainly from rural Turkey. Turkish people of second and even third generation find their spouse mostly in their homeland. Mixed marriage between Turkish people and authentic Dutch is not present.

Control group

A total of 3,626 patients undergoing endoscopy did not have macroscopic abnormalities in colon or rectum. Of these 356 (9.8%) were Turkish. This number reflects the percentage of this population in the Zaanstreek region. It can be concluded that Turkish patients undergo colonoscopy as often as authentic Dutch. One hundred and fifty-five (43%) Turkish patients were male. In the authentic Dutch patients this was 1,281 (39%) (P = ns).

Colorectal cancer

In the study period, 907 patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Of these 13 (1.5%) were of Turkish descent (10 men and 3 women). The remaining 894 were authentic Dutch (473 men and 421 women). There was no difference in gender between both groups.

Table 1 shows the localisation of the cancer in both groups of patients. There was no significant difference. Two Turkish patients (15%) with cancer had concomitant polyps. In the authentic Dutch group this was 290 (32%) (P = ns).

Table 1.

Localisation of the cancers on both groups of patients

| Authentic Dutch | Turkish | |

|---|---|---|

| Rectum | 189 | 4 |

| Sigmoid | 367 | 6 |

| Descending colon | 41 | – |

| Transverse colon | 57 | – |

| Ascending colon | 133 | 4 |

| Cecum | 115 | – |

In one Turkish patient a double tumor was diagnosed in the sigmoid and the ascending colon

P = ns

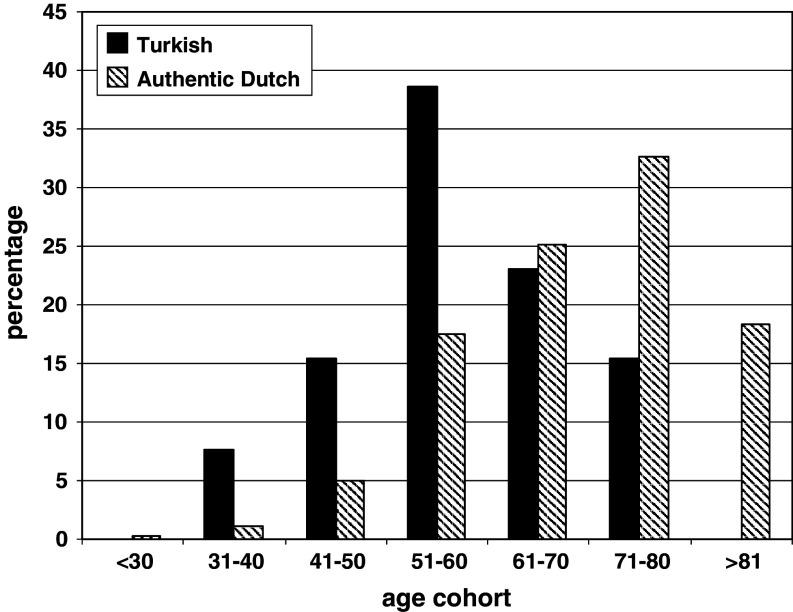

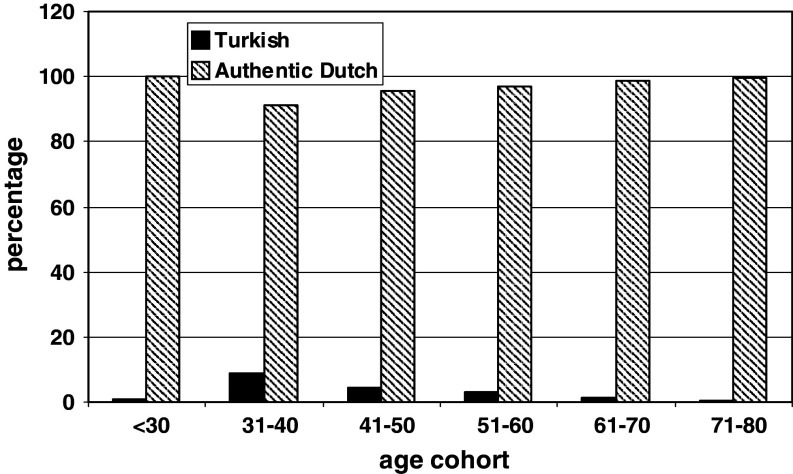

Mean age of Turkish cancer patients was significantly lower compared with the authentic Dutch, 57 years (range 35–75) versus 69 years (range 25–96), P < 0.001. Figure 1 shows the distribution of different age cohorts in both groups. Figure 2 shows the distribution of Turkish patients and authentic Dutch in each age cohort. There was an equal percentage of Turkish patients and authentic Dutch in every age cohort. Only in the oldest age cohort, there is an under representation of Turkish patients.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of colorectal cancer in the age cohorts in Turkish patients and authentic Dutch

Fig. 2.

Distribution of colorectal cancer in each age cohort

Polyps

A total of 2,744 patients had one or more polyps during endoscopy. There were 2,705 authentic Dutch (1,386 men, 1319 women) and 39 Turkish patients (25 men, 14 women). There was no significant difference in gender.

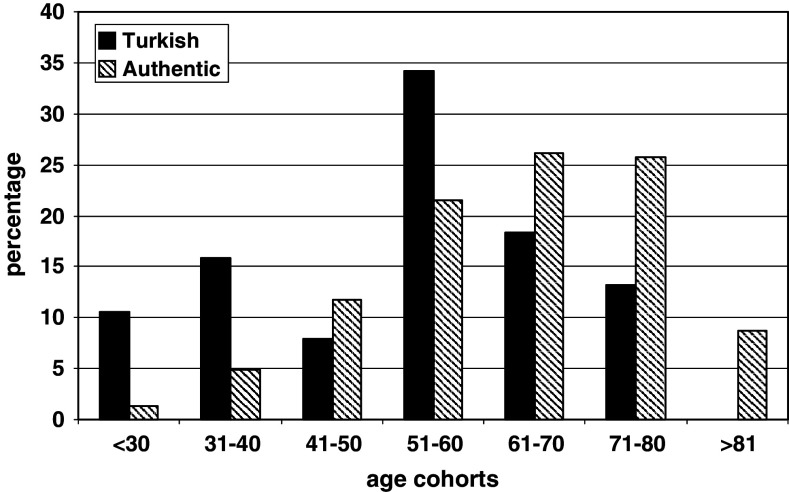

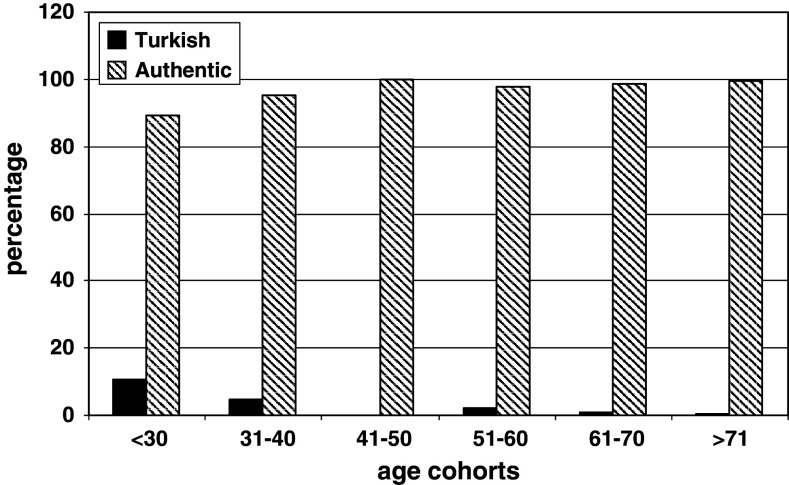

Turkish patients with polyps were significantly younger, 52.9 years (range 24–82) versus 63.4 years (range 17–96) (P < 0.001). Figure 3 shows the age cohorts of both groups of patients. Figure 4 shows the percentage of Turkish patients and authentic Dutch in each age cohort.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of polyps in the age cohorts in Turkish patients and authentic Dutch

Fig. 4.

Distribution of polyps in each age cohort

Unfortunately in 19% of the Turkish patients and 20% of the authentic Dutch no data were available on histology of the removed polyps (P = ns). From the authentic Dutch 2,126 cases and from the Turkish patients 31 cases were evaluable. Tables 2 and 3 show the histological characteristics in both groups.

Table 2.

Histological characteristics of the polyps in both groups of patients

| Polyp | Turkish | Authentic Dutch |

|---|---|---|

| Tubular adenoma | ||

| Low-grade dysplasia | 16 | 933 |

| Moderate dysplasia | 7 | 242 |

| High-grade dysplasia | 1 | 19 |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | ||

| Low-grade dysplasia | 1 | 29 |

| Moderate dysplasia | 1 | 110 |

| High-grade dysplasia | – | 14 |

| Villous adenoma | ||

| Low-grade dysplasia | – | 70 |

| Moderate dysplasia | 1 | 134 |

| High-grade dysplasia | – | 22 |

| Inflammatory polyp | 2 | 48 |

| Unknown histology | 8 | 521 |

| Haemangioma | 1 | |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 1 | 566 |

Table 3.

The histological characteristics of the adenomas in both groups

| Turkish | Authentic Dutch | |

|---|---|---|

| Tubular adenoma | 24 (88.8%) | 1194 (79%) |

| Tubulovillous adenoma | 2 (7.4%) | 153 (10.1%) |

| Villous adenoma | 1 (3.8%) | 163 (10.9%) |

P = ns

Adenomas were diagnosed in 27 out of 31 Turkish patients and in 1,510 out of 2,126 authentic Dutch (P = ns).

There was no difference in histology of the adenomas between both groups.

In 83 authentic Dutch patients a macroscopically benign polyp was removed which contained cancer.

None of the polyps removed in Turkish patients contained cancer.

Discussion

It is interesting to study the morbidity patterns in individuals of different races of ethnicity. Socioeconomic differences, genetic background and environmental factors play essential roles in development and expression of diseases.

The Zaans Medical Centre is a regional hospital and the patient adherence is higher than the population in the region. Hence, it can be assumed that all people, including the Turkish immigrants, visit this hospital seeking medical care. Ten percent of people living in the Zaanstreek region are of Turkish descent. The present study clearly shows that colorectal cancer and its precursor lesion, the adenoma is rare in patients from Turkish descent. Only 1.4% of patients with colorectal cancer are Turkish.

All inhabitants in the Netherlands regardless of race or ethnicity have health insurance. There is no difference in accessibility of health care facilities. This is shown in the control group. The percentage of patients of Turkish descent undergoing colonoscopy equals the percentage in the population in the Zaanstreek region. Hence, it can be concluded that the low prevalence of colorectal cancer and adenomas cannot be explained by a lower access to medical care by Turkish people.

Unfortunately there are no exact data available on the prevalence of colorectal cancer in Turkey. Real incidence in Turkey has never been properly studied nationwide.

The Ministry of Health established a passive cancer registration system in 1983. There has been a threefold increase in cancer incidence in the period of 1983–1999. Probably this increase is mainly due to better registration (Turkey Health report, the Ministry of Health of Turkey, february 2004). Data on colorectal cancer are not registered separately. In most reports it is filed under the heading gastrointestinal cancer. In a 12-month survey, the incidence of colorectal cancers was lower than the series reported from the United States (Turhal et al. 2003). In another paper, in which the presence of cancer in a specified region in Turkey was reported, prevalence of colorectal cancer was 7.8% of all cancers in women and 13.6% in men (Köksal et al. 2009). Incidence of colorectal cancer is reported to be low in Turkey (Vetter et al. 1992). In all age cohorts colorectal cancer is rare. It is not in the top five types of cancer.

The majority of cancer patients (74%) in Turkey did not have a family history of cancer. Genetic abnormalities play an important role in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Despite the low incidence, the mutations are as often present in Turkey compared with the rest of the world (Akkiprik et al. 2008).

The reason for the difference in prevalence of colorectal cancer is not obvious. In the literature it is postulated that certain diets can be protective against the development of cancer (Wu et al. 2009; Smith-Warner et al. 2002; Mathew et al. 2004; Millen et al. 2007). The major difference in diet between authentic Dutch and the Turkish people is that Turks consume more fibre. Although there are no exact data in the Zaanstreek region on fibre intake, it is wellknown that Turkish people eat lots of fruit and vegetables. This is not only true for the first generation born in Turkey, but also for Turkish people born and raised in the Zaanstreek region. Of course, it is very interesting to study the prevalence of adenomas and CRC in the years to come. It can be expected that, especially young people, adapt to the regional food pattern. Possibly the prevalence of colorectal neoplasia will rise in the next decennia.

The Turkish patients are younger than the authentic Dutch. This was already noticed in Turkey. Subjects below the age of 55 years with sedentary jobs in Turkey show a higher risk for colorectal cancer than did the older age group (Vetter et al. 1992) probably due to adoption of a more western lifestyle.

However, under representation of the oldest age cohort in the Turkish population can be a flaw. In the younger age cohorts there is no difference between the percentage of Turkish patients and authentic Dutch.

The conclusion of the present study is that colorectal cancer is rare amongst patients of Turkish descent living in the Zaanstreek region. Obviously there is still an under representation of the oldest cohorts of patients of Turkish descent. But if the oldest age cohorts were excluded, the fact remains that there is a similar age distribution in both age groups and that Turkish cancer patients are younger than the authentic Dutch patients.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Akkiprik M, Cehkel CA, Düsünceh F, Sönmez O, Güllüoğlu BM, Sav A, Ozer A (2008) Relationship between overexpression of ras p21 oncoprotein and K-ras codon 12 and 13 mutations in Turkish colorectal cancer patients. Turk J Gastroenterol 19:22–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu KC, Tarone RE, Chow WH, Alexander GA (1995) Colorectal cancer trends by race, anatomic subsites, 1975–1991. Arch Fam Med 4:849–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köksal A, Sorkun HÇ, Demirhan H, Tomatur AG, Alan T, Özerdem F (2009) Evaluation of cancer records from 2000–2004 in Denizli Turkey. Genet Mol Res 8:64–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le H, Ziogas A, Taylor TH, Lipkin SM, Zell JA (2009) Survival of distinct Asian groups among colorectal cancer cases in California. Cancer. 115(2):259–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffeld RJLF (2005) Diverticulosis of the colon is rare amongst immigrants living in the Zaanstreek region in the Netherlands. Colorectal Dis 7:559–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffeld RJ, van der Putten AB (2004) Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in immigrants living in the Zaanstreek region in the Netherlands. Dis Esophagus 17(1):87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffeld RJLF, van der Putten ABMM (2005) The annual yield of diagnostic endoscopy of the lower digestive tract. Eur J Int Med 16:37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney MC, Va P, Stevens A, Kahn AR, Michalek AM (2009) Fifty years of cancer in an American Indian population. Cancer 115(2):419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew A, Peters U, Chatterjee N, Kulldorff M, Sinha R (2004) Fat, fiber, fruits, vegetables, and risk of colorectal adenomas. Int J Cancer 108(2):287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millen AE, Subar AF, Graubard BI, Peters U, Hayes RB, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, Ziegler RG PLCO, Team Cancer Screening Trial Project (2007) Fruit and vegetable intake and prevalence of colorectal adenoma in a cancer screening trial. Am J Clin Nutr 86:1754–1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, Howe HL, Weir HK, Rosenberg HM, Vernon SW, Cronin K, Edwards BK (2000) The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer 88:2398–2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rim SH, Seeff L, Ahmed F, King JB, Coughlin SS (2009) Colorectal cancer incidence in the United States, 1999–2004: an updated analysis of data from the National Program of Cancer Registries and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and end results program. Cancer 115(9):1967–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Jemal A, Thun MJ, Hao Y, Ward EM (2008) Trends in the incidence of colorectal cancer in relation to county-level poverty among blacks and whites. J Natl Med Assoc 100(12):1441–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siesling S, van der Aa MA, Coebergh JW, Pukkala E (2008) Working group of the Netherlands cancer registry. Time-space trends in cancer incidence in the Netherlands in 1989–2003. Int J Cancer 122:2106–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Warner SA, Elmer PJ, Fosdick L, Randall B, Bostick RM, Grandits G, Grambsch P, Louis TA, Wood JR, Potter JD (2002) Fruits, vegetables, and adenomatous polyps: the Minnesota cancer prevention research unit case–control study. Am J Epidemiol 155:1104–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbu I, Kunst AE, Vlems FA, Visser O, Bos V, Deville W, Nijhuis HG, Coebergh JW (2006) Cancer mortality rates among first and second generation migrants in the Netherlands: convergence toward the rates of the native Dutch population. Int J Cancer 119:2665–2672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turhal NS, Aliustaoglu M, Gurses I, Gumus M, Atalay G, Karamanoglu A, Sengoz M (2003) Neoplastic diseases prevalence in a Turkish university hospital. J BUON 8:45–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkey Health report, the Ministry of Health of Turkey, february 2004, http://www.saglik.gov.tr/EN/Tempdosyalon/215_turkeyhealthreport.pdf

- Vetter R, Dosemeci M, Blair A, Wacholder S, Unsal M, Engin K, Fraumeni Jr JF (1992) Occupational physical activity and colon cancer risk in Turkey. Eur J Epidemiol 8:845–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir HK, Thun MJ, Hamkey BF, Ries LA, Howe HL, Wingo PA, Jemal A, Ward E, Anderson RN, Edwards BK (2003) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:1276–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Dai Q, Shrubsole MJ, Ness RM, Schlundt D, Smalley WE, Chen H, Li M, Shyr Y, Zheng W (2009) Fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with lower risk of colorectal adenomas. J Nutr 139(2):340–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]