Abstract

Hemoptysis in patients with lung cancer is not uncommon and sometimes have dangerous consequences. Hemoptysis has been managed with various treatment options other than surgery and medicine, such as endobronchial tamponade, transcatheter arterial embolization and radiation therapy. However, these methods can sometimes be used only temporarily or are not suitable for a patient's condition. We present a case in which uncontrollable hemoptysis caused by central lung cancer was successfully treated by inserting a covered self-expanding bronchial stent. The patient could be extubated and was able to undergo further palliative therapy. No recurrent episodes of hemoptysis occurred for the following three months. As our case, airway stenting is a considerable option for the tamponade of a bleeding lesion that cannot be successfully managed with other treatment methods and could be used to preserve airway patency in a select group of patients.

Keywords: Hemoptysis, Stents

INTRODUCTION

Hemoptysis is not uncommon manifestation of pulmonary disease including lung cancer (1, 2). Hemoptysis can be fatal and therefore early detection and proper management is critical. Management options for hemoptysis include pharmacological or bronchoscopic therapy, transcatheter embolization and surgical resection. Endobronchial tamponade is another treatment option for hemoptysis, especially in cases involving central airway lesions. Endobronchial tamponade is used not only to control bleeding but also to protect the contralateral lung. Endobronchial tamponade is commonly achieved using a double-lumen endobronchial tube or by the placement of an endobronchial balloon. These methods are effective, but require prolonged mechanical ventilation (3).

We present a case in which bleeding caused by cancer in the left central lung was successfully managed by tamponade with a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered self-expanding bronchial stent that allowed the patient to be extubated and to undergo further palliative therapy.

CASE REPORT

49-yr-old male visited our hospital because of dysphasia, hoa-rseness and a 10 kg weight loss experienced over the previous three months. Approximately five months prior to this visit, the patient was diagnosed with a central lung mass in the left hilar area based on a chest radiograph obtained during a health check. However, the patient refused further evaluation at the time. We performed computed tomography (CT) imaging, which revealed a huge central lung mass obstructing the left main bronchus and the proximal portion of the left upper and lower lobar bronchi. This mass invaded the carina, adjacent esophagus and left main pulmonary artery surrounding the descending thoracic aorta. A bronchoscopic biopsy was performed and the mass was finally confirmed as non-small cell lung cancer, specifically a squamous cell carcinoma. After a 12 cm covered esophageal stent was inserted to relieve dysphagia, chemotherapy was started. About one month later, the patient revisited the emergency department with sudden aggravation of dyspnea and coughing. Respiration rates were initially 36/min and increased to 44/min for one hour after hospitalization. The patient was intubated for mechanical ventilator support and was managed in the intensive care unit. Blood-tinged sputum developed during the first day of admission. Three days after admission, a chest radiography showed the left lung had totally collapsed and bloody secretions were aggravated with no evidence of coagulopathy. The hemoglobin level had dropped from 10.7 g/dL to 8.8 g/dL during the course of one day. At this time, a bronchoscopic examination demonstrated the presence of an endoluminal protruding mass with extrinsic compression from the distal trachea to the left main bronchus. The orifice of the left main bronchus was completely obstructed by the mass and was coated by bloody and fibrinous clots. There was diffuse bleeding from the mucosal surface of the mass without a localized focus. Epinephrine was sprayed on the area to control the bleeding. However, this was only temporarily effective and bleeding continued intermittently. From the eighth day after admission, blood was aspirated through endotracheal tube continuously. Bronchial artery embolization could not be considered as an option to control the bleeding, because it was not active arterial bleeding and there was no prominent contrast enhancement of the mass as seen on a CT scan. Surgical resection also could not be considered because of the advanced stage of the cancer. On the tenth day after admission, a bronchial stent was inserted to achieve a tamponade effect to stop the bleeding and to maintain luminal patency of the left main bronchus. A hydrophilic guidewire (Radiofocus: Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted under bronchoscopic guidance and an angiographic catheter (Angled Taper; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was then advanced into the lower lobar bronchus. A small amount of non-ionic contrast material was injected into the airway to identify the bronchial tree, as we were unable to discriminate the airway on a fluoroscopic image due to the total collapse of the left lung. A stiff guidewire (Amplatz Super Stiff; Boston Scientific, Watertown, MA, USA) was inserted into the left lower lobar bronchus and a 12 mm-6 cm self-expanding polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-covered nitinol stent (Taewoong Medical, Seoul, Korea) was deployed in the left main bronchus under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 1). Blood in the endotracheal tube decreased markedly and dyspnea was relieved soon after bronchial stent placement. Two days after the stent placement, the patient was extubated and blood-tinged sputum had disappeared completely four days later (Fig. 2). Radiation therapy was started eleven days after stent placement. During radiation therapy, a total collapse of the left lung again developed. A mass in the proximal left main bronchus that was not covered by the stent was removed by bronchoscopy and left lung aeration improved. The patient expired three months after stent placement due to disease progression. During this period, there was no frank hemoptysis, except for several episodes of blood-tinged sputum.

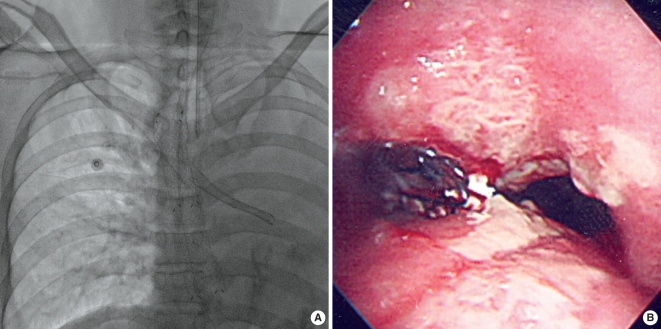

Fig. 1.

A bronchial stent was placed in the left main bronchus. (A) A fluoroscopic image shows the bronchial stent and a totally collapsed left lung. (B) Bronchoscopy performed just after the bronchial stent placement shows the proximal end of the stent, which was exactly positioned at the orifice of the left main bronchus.

Fig. 2.

A multi-planar reformatted oblique coronal CT image obtained six days after the bronchial stent placement shows the bronchial stent in the left main bronchus with internal bubbly material, suggesting secretion and an aerated left lung.

DISCUSSION

Common causes of hemoptysis are benign diseases; however, hemoptysis can also occur in patients with lung cancer with a rate as high as 27% (1, 2). Hemoptysis due to lung cancer is usually mild, resulting in blood-streaked sputum (4). In most cases, hemoptysis results from the erosion of small, friable mucosal vessels. Massive hemoptysis can sometimes occur due to malignant invasion of central pulmonary vessels by tumors (4). Hemoptysis can be life threatening and the condition can delay the proper treatment of underlying disease.

Hemoptysis can be managed by localizing the bleeding source and by providing specific treatment. To protect the contralateral lung, patients may be selectively intubated or ventilated with a double-lumen endotracheal tube. There have been occasional reports of successful tamponade by the use of airway balloons deployed by bronchoscopy (3). However, these methods offer only temporary relief and prolonged mechanical ventilation is needed. Conventional radiation therapy also offers excellent palliation of hemoptysis in lung cancer in up to 80% of cases (5). However, patients must be physically able to undergo radiation therapy, and sometimes multisession treatments are necessary. Bronchial artery embolization has been accepted as an effective modality to temporize the bleeding. However, most reports of bronchial artery embolization are limited. with a few cases of lung cancer (6-8).

To the best of our knowledge, there is one case report that has described airway stent placement to achieve tamponade and isolation of the bleeding source from lung cancer (9). However, bleeding was successfully controlled after the second stent placement that isolated the bleeding mass lesion in the previous case. We achieved successful tamponade with the first stent in the main bronchus, as the lung cancer, which was the source of bleeding, was centrally located. We also achieved patency of the stenotic main bronchus that had been invaded by the tumor. The second event of left lung collapse without hemoptysis occurred during radiation therapy. Considering the relative short period and the findings of bronchoscopy that was performed just after stent placement and showed the exact location of the proximal end of the stent at the orifice of the left main bronchus, we presumed that the finding was probably due to minimal distal migration of the stent rather than tumor overgrowth. We used a full covered stent; therefore, the possibility of migration was inevitable. Covered airway stents are effective to prevent tumor ingrowth or mucosal hyperplasia; however, stent migration, accumulation of secretion and sometimes membrane disruption can occur (10). Other significant complication such as an aortobronchial fistula, especially in cases with non-covered stent, have also been rarely reported (11). A covered airway stent is designed as a retrievable stent and the sent can be removed when the patient responds to radiotherapy/chemotherapy and no longer requires the stent. However, stent removal is not commonly performed for malignant strictures and removal time has not been established even for benign lesions (10, 12-14). The effectiveness of stent placement according to the location or tumor type has also not been established. Therefore, a further study is needed.

In conclusion, airway stenting is a considerable option for the tamponade of a bleeding lesion in an airway that cannot be successfully managed with other treatment methods. Airway stenting also could be used to preserve airway patency in a select group of patients.

References

- 1.Chute CG, Greenberg ER, Baron J, Korson R, Baker J, Yates J. Presenting conditions of 1539 population-based lung cancer patients by cell type and stage in New Hampshire and Vermont. Cancer. 1985;56:2107–2111. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851015)56:8<2107::aid-cncr2820560837>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RR, McGregor DH. Hemorrhage from carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1980;46:200–205. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800701)46:1<200::aid-cncr2820460133>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dweik RA, Stoller JK. Role of bronchoscopy in massive hemoptysis. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:89–105. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson JL. Manifestations of hemoptysis. How to manage minor, moderate, and massive bleeding. Postgrad Med. 2002;112:101–106. 108–109, 113. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2002.10.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langendijk JA, ten Velde GP, Aaronson NK, de Jong JM, Muller MJ, Wouters EF. Quality of life after palliative radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:149–155. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mal H, Rullon I, Mellot F, Brugiere O, Sleiman C, Menu Y, Fournier M. Immediate and long-term results of bronchial artery embolization for life-threatening hemoptysis. Chest. 1999;115:996–1001. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osaki S, Nakanishi Y, Wataya H, Takayama K, Inoue K, Takaki Y, Murayama S, Hara N. Prognosis of bronchial artery embolization in the management of hemoptysis. Respiration. 2000;67:412–416. doi: 10.1159/000029540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kvale PA, Simoff M, Prakash UB. Lung cancer. Palliative care. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):284S–311S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.284s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandes JC, Schmidt E, Yung R. Occlusive endobronchial stent placement as a novel management approach to massive hemoptysis from lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:1071–1072. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318183af75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nam DH, Shin JH, Song HY, Jung GS, Han YM. Malignant esophageal-tracheobronchial strictures: parallel placement of covered retrievable expandable nitinol stents. Acta Radiol. 2006;47:3–9. doi: 10.1080/02841850500334989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onishi H, Kuriyama K, Komiyama T, Tanaka S, Marino K, Tsukamoto T, Araki T. A case of aorto-bronchial fistula after insertion of left main bronchial self-expanding metallic stent in a patient with recurrent esophageal cancer. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:288–290. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-0052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song HY, Shim TS, Kang SG, Jung GS, Lee DY, Kim TH, Park S, Ahn YM, Kim WS. Tracheobronchial strictures: treatment with a polyurethane-covered retrievable expandable nitinol stent--initial experience. Radiology. 1999;213:905–912. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc02905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JH, Shin JH, Song HY, Shim TS, Yoon CJ, Ko GY. Benign tracheobronchial strictures: long-term results and factors affecting airway patency after temporary stent placement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1033–1038. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyazawa T, Yamakido M, Ikeda S, Furukawa K, Takiguchi Y, Tada H, Shirakusa T. Implantation of ultraflex nitinol stents in malignant tracheobronchial stenoses. Chest. 2000;118:959–965. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]