Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between hospital context, nursing unit structure, and patient characteristics and patients’ satisfaction with nursing care in hospitals.

Background

Although patient satisfaction has been widely researched, our understanding of the relationship between hospital context and nursing unit structure and their impact on patient satisfaction is limited.

Methods

The data source for this study was the Outcomes Research in Nursing Administration Project, a multi-site organizational study to investigate relationships among nurse staffing, organizational context and structure and patient outcomes. The sample for this study was 2720 patients and 3718 RNs in 286 medical-surgical units in 146 hospitals.

Results

Greater availability of nursing unit support services and higher levels of work engagement were associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction. Older age, better health status and better symptom management were also associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction.

Conclusions

Organizational factors in hospitals and nursing units, particularly support services on the nursing unit and mechanisms that foster nurses’ work engagement and effective symptom management, are important influences on patient satisfaction.

A federal survey based on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) paints a sobering picture of patients’ experiences in U.S hospitals with many respondents reporting dissatisfaction with some aspects of their care. (1, 2) Many patients reported a lack of courtesy and respect, problems managing their pain, and poor communication with providers. Understanding patients’ satisfaction is important so caregivers can better anticipate patient needs and develop plans to meet them. From an organizational perspective, creating work environments that foster higher levels of patient satisfaction depends on understanding the interrelationships among hospital and nursing unit characteristics and their impact on patient satisfaction. Therefore, we examined relationships among organizational context (characteristics of the hospital and nursing unit environments), patient characteristics, nursing unit structure (unit capacity, work engagement and work conditions), and effectiveness (patient satisfaction) in acute care hospitals.

Research Model

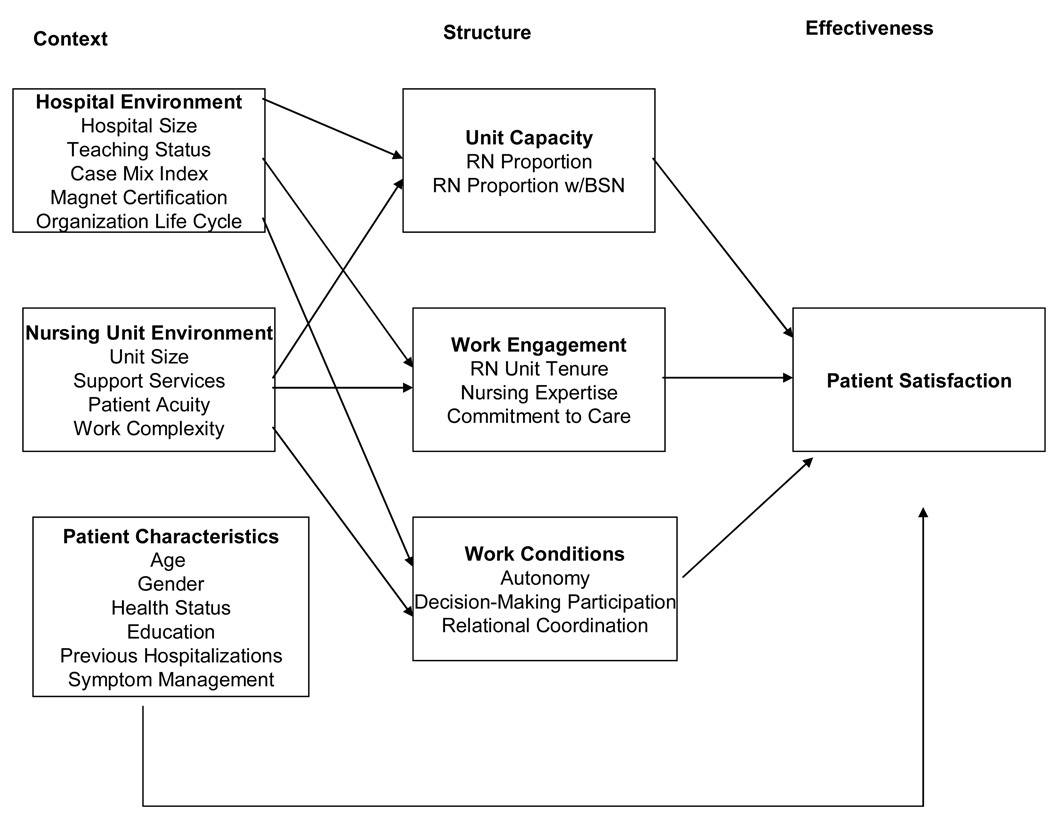

The major constructs of our research model and the variables used to measure them are presented in Figure 1. Below we provide more details about the model.

Figure 1.

Research Model

Context

Contextual variables representing the hospital environment included hospital size, teaching status, case mix index, Magnet™ certification, and organizational life cycle. Hospital size is important because patients in smaller hospitals report higher levels of satisfaction with their care than patients in larger hospitals. (3) Hospital teaching status is thought to be important to patient satisfaction because patients in teaching hospitals report more complicated problems than those in non-teaching hospitals. (3). Case mix index was included because patients who are more severely ill tend to report lower levels of satisfaction (4) than the less severely ill. Magnet status was included because Magnet hospitals have been linked to higher patient satisfaction. (5) Finally, organizational life cycle, which refers to changes in the pattern of hospital admissions over 2 consecutive years, was included because previous studies (6) have found that changes in hospital admission patterns negatively affect the professional practice environment on nursing units which may negatively influence patient satisfaction.

Contextual factors of the nursing unit include unit size, availability of support services, patient acuity, and work complexity. Similar to the relationship between hospital size and patient satisfaction, patients on larger nursing units tend to be less satisfied. (7) Patient satisfaction may also be influenced by the degree of support provided to nurses on the units (6) because support services allow nurses more time for direct patient care. High patient acuity levels on the unit, and the corresponding complexity of the work required to care for them, can increase the demands that are placed on nurses limiting the time nurses can devote to meeting patient needs which then may influence patient satisfaction.

We also included patient characteristics that have been consistently identified as important influences on patient satisfaction including age, gender, health status, education, and prior experiences with the health care system. (3, 12) Because we expected that the extent to which nurses were able to respond to patient symptoms would influence their overall level of satisfaction, we also included patients’ perceptions of management of their symptoms.

Structure

Structure was conceptualized as nurse staffing and the practice environment in which care was delivered. Based on prior work, we included unit capacity, work engagement and work conditions as structural variables. (7) Because patient satisfaction has been linked to nurse staffing levels, with patients reporting higher levels of satisfaction on units with higher proportions of RN caregivers and with a higher proportion of RNs with baccalaureate degrees, (5), our measure of unit capacity reflects registered nurse (RN) staffing and the educational preparation of RNs on the unit.

Work engagement is integral to the practice environment and was defined conceptually as personal involvement in and commitment to the work that motivates an employee to invest greater time, energy, and initiative in completing job assignments. (8) Highly engaged nurses may respond proactively to patient needs, increasing patient satisfaction with the nursing care that they receive. Three important aspects of work engagement are tenure on the unit, expertise, and commitment to care. Nurses’ tenure on the unit is important because nurses who have worked longer on the unit should be more familiar with the type of patients who receive care on their unit and may be better able to anticipate their needs. In addition, nursing expertise and commitment to care are consistently documented as important contributors to patient satisfaction. (9–10)

Work conditions in which nurses have autonomy, participate in decision-making, and engage in collaborative relationships with other providers can produce highly satisfied patients. (11, 12) Autonomy, which refers to the degree to which nurses have independence or freedom in their jobs, and participation in decision making, which refers to the possession of authority to make decisions, are important components of professional practice and have been positively associated with patient outcomes. (5) These factors provide nurses with the discretion needed to act quickly to meet patient needs, which may result in high levels of patient satisfaction. Moreover, workgroups with strong relational coordination may be more likely to achieve high levels of patient satisfaction because they accurately communicate important patient information, share knowledge, and engage in effective group problem solving. (13)

Methods

Design

This study was conducted with data from the Outcomes Research in Nursing Administration Project-II. ORNA-II is a large, multi-site study designed to investigate relationships among hospital context, structure and organizational, nurse and patient outcomes. (14) After obtaining IRB approval, ORNA-II data were collected in 2003 and 2004 on 2 medical-surgical units in 146 U.S. acute care hospitals that were randomly selected from the 2002 American Hospital Association Guide to Hospitals. Eight nursing units withdrew from the study, resulting in a final sample of 278 units.

Data Collection

Each hospital selected an on-site study coordinator to assist with data collection after they completed a 1 1/2 day training session with the study team.

Registered nurses with more than 3 months experience on their unit completed 3 questionnaires, each with a different set of instruments, over a 6 month period of time. RN response rates were 75% (N=4,911) for the first data collection, 58% (N=3,689) for the second collection, and 53% (N=3,272) for the third collection. Nurse data from the first 2 waves of data collection were included in the analysis described here.

Patients completed a questionnaire detailing their satisfaction with their care. Ten patients were randomly selected from each nursing unit who were at least 18 years of age, hospitalized for a minimum of 48 hours, able to speak and read English and not planned for imminent discharge. A total of 2720 patients responded (response rate 91%).

Measures

Context

Hospital Environment Variables

Hospital size was measured as the number of staffed beds and teaching status was measured as the ratio of medical and dental residents to the number of hospital beds; these data were obtained from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals. Case mix index, designed to capture illness severity, was measured using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services case mix index. Magnet status was measured by whether the hospital was certified by the American Nurses Credentialing Center for Excellence in Nursing. Organization life cycle was measured by classifying hospitals as “growers” if admissions to the hospital increased 5% or more during 2 consecutive years; “decliners” if admissions had not increased or decreased more than 5% during 2 consecutive years; “unstable” if admissions had increased or decreased more than 5% in one but not both consecutive years; and “highly unstable” if admissions had increased more than 5% in the first years and then decreased more than 5% in the second year or decreased more than 5% in the first year and then increased more than 5% in the second year. (14) Study coordinators obtained the data on Magnet status and organization life cycle.

Nursing Unit Environment Variables

Unit size was measured as the number of staffed beds. Support services availability was measured using a 21-item checklist of unit-level support services, including, for example, respiratory therapy services and computerized order entry systems. (6). Patient acuity was measured using a 14-item Likert-type questionnaire that elicited nurses’ perceptions of patient-related demands on their unit including the type and variety of patients admitted to the unit and the extent to which patient conditions changed rapidly. (6, 15–16) Work complexity was measured by a 7-item Likert-type questionnaire on which nurses rated the extent to which their work is characterized by frequent interruptions or unanticipated events. (17) Cronbach’s alpha for perceptual measures can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Variables in the Model.

| Variable: | Mean (S.D) | % | Coefficient α |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORGANIZATIONAL CONTEXT | |||

| Hospital Environment | |||

| Hospital Size (number of staffed beds) | 345.8 (185.2) | ||

| Teaching Status | 0.13 (0.25) | ||

| Case Mix Index | 1.44 (0.31) | ||

| Magnet Certification (%) | 13 | ||

| Organizational Life Cycle (%) | |||

| Stable | 57 | ||

| Growers | 5 | ||

| Decliner | 3 | ||

| Highly unstable | 2 | ||

| Unstable | 2 | ||

| Nursing Unit Environment | |||

| Unit Size (number of staffed beds) | 33.5 (11.1) | ||

| Support Services Availability (scale range 0–42) | 32.4 (2.5) | 0.80 | |

| Patient Acuity (scale range 14–70) | 45.6 (3.6) | 0.81 | |

| Work Complexity (scale range 7–42) | 26.8 (3.5) | 0.85 | |

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 56.9 (7.5) | ||

| Gender (% females) | 56 | ||

| Health Status | 3.5 (0.4) | ||

| Education (% ≥ high school) | 50 | ||

| Prior Hospitalization Experience in Past Year (%) | 53 | ||

| Symptom Management | 27.4 (2.4) | 0.86 | |

| NURSING UNIT STRUCTURE | |||

| Unit Capacity | |||

| RN Proportion | 59.4 | ||

| RN Proportion with BSN | 36.5 | ||

| Work Engagement | |||

| RN Unit Tenure (number of months) | 74.7 (33) | ||

| Nursing Expertise (scale range 8–48) | 42.4 (2.1) | 0.92 | |

| Commitment to Care (scale range 8–48) | 36.6 (19.4) | 0.82 | |

| Work Conditions | |||

| Autonomy (scale range 16–112) | 89.6 (6.3) | 0.92 | |

| Participation in Decision-Making (scale range 6–30) | 15.7 (2.1) | 0.78 | |

| Relational Coordination (scale range 63–315) | 226.1 (12.7) | 0.95 | |

| ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS | |||

| Patient Satisfaction | 44.4 (2.76) | 0.97 |

Note. Variables measured at the nominal or ordinal level were summarized using %; Variables measured at the interval or ratio level were summarized using means and standard deviations.

Patient Variables

Patients recorded their age, gender, education level, and whether they had been hospitalized in the last year. Patients also rated their health status, with responses ranging from very good to very poor. Finally, patients rated the extent to which nurses managed their symptoms in a 5-item Likert-type scale with response options ranging from much more than expected to much less than expected. (18)

Organizational Structure

Unit capacity was measured with a factor-based scale as the proportion of RNs among the total nursing staff on each unit and the proportion of RNs with a baccalaureate degree in nursing. Work engagement was measured as a factor-based scale that included tenure on the unit, and aggregated responses to 16 Likert-type items from the Nursing Expertise and Commitment to Care Scale. (19) Work conditions was measured as a factor-based scale based on the aggregated scores obtained from 3 separate instruments. Autonomy was measured with the 16-item Control over Practice Scale. (20) Participation in decision making was measured with a 6-item 5-point Likert-type scale in which nurses rated their involvement in unit decisions. (21) Relational coordination was measured using the 5-point-Likert type Relational Coordination Scale. (22)

Organizational Effectiveness

Patient satisfaction

Patients rated thirteen items on a 4 point scale ranging from poor to excellent (7). Sample items included the ability of caregivers to work together, the promptness of nurses in answering calls, and the quality and thoroughness of the nursing care. Patients were also asked to rate on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to always, the extent to which they perceived respect and dignity from nurses, if they considered the hospital a place for good nursing care, and whether they would be comfortable recommending the hospital to a friend or relative.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with path analysis using the Mplus statistical program. (23) First, the structural variables were regressed on the contextual variables and then the patient satisfaction variable was regressed on the structural variables and the patient characteristics variables. We used the “complex” modeling method because it generates correct standard errors for nested data (2 nursing units in a single hospital). We also evaluated the theoretical model with tests of model fit including the chi square statistic (in which a non-significant value indicates a well-fitting model), goodness of fit (GFI) and Tucker-Lewis (TLI) indices, with values close to 1.0 for each indicating a well-fitting model, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values less than 0.05 indicating a well-fitting model.

Results

Descriptive Results

Descriptive statistics for all study variables along with relevant psychometric information are presented in Table 1. Hospitals reported, on average, 345 beds (S.D. = 185), with a case mix index of 1.44 (S.D. = .317). The typical patient was 56 years, female, and had been hospitalized at least once during the past year. On average, patients rated their health status as fair to good. Patients rated their satisfaction between “good” and “excellent” (mean 44.4 out of a total possible score of 52).

Impact of Hospital and Nursing Unit Characteristics on Unit Structure

Unit Capacity

Based on unstandardized regression coefficients (Table 2), we found higher levels of unit capacity in larger hospitals, teaching hospitals, and those with more severely ill patients, but lower levels of unit capacity in hospitals characterized by declining or highly unstable admission patterns. Magnet status was not associated with unit capacity. None of the nursing unit characteristics significantly predicted unit capacity.

Table 2.

Unstandardized Parameter Estimates and Standard Errors for Variables in Model.

| Unit Capacity | Work Engagement | Work Conditions | Patient Satisfaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std Error | Estimate | Std Error | Estimate | Std Error | Estimate | Std Error | |

| Hospital Environment | ||||||||

| Hospital Size | 0.001 * | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||

| Teaching Status | 1.808 ** | 0.425 | −0.028 | 0.554 | 0.016 | 0.914 | ||

| Case Mix Index | 0.545 * | 0.257 | 0.998 | 0.527 | 0.464 | 0.390 | ||

| Magnet Certification | 0.377 | 0.317 | 0.181 | 0.455 | 1.116 ** | 0.383 | ||

| Organizational Life Cycle | ||||||||

| Growers | 0.483 | 0.273 | −1.299 * | 0.626 | −0.900 | 0.555 | ||

| Decliner | −0.963 * | 0.448 | −0.724 | 0.580 | −1.565 * | 0.731 | ||

| Highly Unstable | −1.014 * | 0.464 | 0.667 | 0.500 | −0.789 | 0.665 | ||

| Unstable | −0.257 | 0.210 | −0.152 | 0.350 | −0.041 | 0.306 | ||

| Nursing Unit Environment | ||||||||

| Unit Size | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.010 | −0.009 | 0.011 | ||

| Support Services Availability | 0.016 | 0.042 | 0.090 | 0.068 | 0.214 ** | 0.066 | 0.219 *** | 0.061 |

| Patient Acuity | 0.024 | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.034 | 0.028 | 0.037 | ||

| Work Complexity | −0.051 | 0.026 | −0.114 ** | 0.048 | −0.212 ** | 0.042 | ||

| Patient Characteristics | ||||||||

| Age | 0.047 ** | 0.019 | ||||||

| Gender (% Females) | 1.309 | 0.769 | ||||||

| Health Status | 0.762 ** | 0.326 | ||||||

| Education | −0.354 | 0.621 | ||||||

| Hospitalization in Past Year | −0.090 | 0.809 | ||||||

| Symptom Management | 0.367 *** | 0.078 | ||||||

| Nursing Unit Structure | ||||||||

| Unit Capacity | −0.112 | 0.106 | ||||||

| Work Engagement | 0.202 *** | 0.063 | ||||||

| Work Conditions | 0.092 | 0.065 | ||||||

| Intercept | −1.571 | 1.814 | −1.594 | 3.575 | −3.056 | 3.024 | 21.465 | 3.517 |

| R2 | 0.255 | 0.097 | 0.258 | 0.313 | ||||

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Work Engagement

The only hospital level variable to predict work engagement was organizational life cycle, with lower levels of work engagement in hospitals classified as growers. The only nursing unit characteristic associated with work engagement was work complexity, which was negatively associated with work engagement.

Work Conditions

Selected hospital and nursing unit level variables predicted work conditions. Nurses in hospitals with a declining pattern of admissions reported poorer work conditions than did nurses in other hospitals. Higher levels of work complexity were also associated with poorer work conditions. In contrast, nurses in Magnet hospitals reported significantly better work conditions than did their non-magnet counterparts. Greater availability of support services on the unit was also associated with better work conditions.

Patient Satisfaction

An initial model regressing patient satisfaction on unit capacity, work engagement, work conditions and patient characteristics fit moderately well (chi square value 49.7, p = .009; CFI = .92; TLI .79; RMSEA = .05), and a modification index suggested that the model could be improved by including the availability of support services as a regressor. Using the suggested modification, we found that support services and work engagement were significantly related to higher levels of patient satisfaction. In addition, patient age, health status, and symptom management were all significantly positively related to higher levels of patient satisfaction. This model had an excellent fit to the data with a chi-square value of 39.5 (df = 31; p = 0.14); CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.92; and RMSEA = 0.03.

Discussion

Hospital characteristics, with the exception of Magnet status, had a significant impact on unit capacity, but none of the nursing unit characteristics predicted unit capacity. This suggests that unit staffing may be determined more by the hospital itself than conditions on the nursing unit. This is surprising because it seems that the size of the nursing unit and the availability of support services, as well as the level of patient acuity and the complexity of the work would have a substantial influence on the composition of the nursing staff.

We can speculate on 2 possible reasons for these findings. The first is that the sample for the ORNA study was comprised of medical, surgical, and medical-surgical units, limiting variability in our measures. This may have obscured possible relationships among these variables. The second reason relates to the use of perceptual measures for patient acuity and work complexity. These variables are extremely difficult to operationalize, and while our measures had acceptable psychometric properties, they may lack sensitivity to adequately capture the full range of patient acuity and work complexity.

We found few significant predictors of work engagement. The finding that hospitals that had a pattern of substantial increases in admissions (i.e., growers) was associated with lower levels of work engagement indicates that nurse executives should be aware of the stress that such rapid growth may place on nurses and their ability to adequately meet patient needs. Nurse staffing should be adjusted to avoid overloading unit staff because of the increased demand that these additional admissions place on them. Such stressors can lead to not only less committed nurses but increased levels of burnout and turnover which may negatively influence patient satisfaction.

Our finding that work complexity was also associated with lower levels of work engagement suggests that nurse executives should implement measures to reduce work complexity, such as improvements in support services and infrastructure, which should reduce nurses’ administrative tasks and increase time available at the bedside. Nurse executives play a critical role in ensuring organizational support for work environments that foster and reward nurses’ personal involvement in and commitment to the work. High levels of support make it more likely that they will become cultural norms in the institution and bolster nurse satisfaction. More satisfied nurses will in turn be more likely to remain on their units, lengthening unit tenure and strengthening nursing expertise, which will lead to more satisfied patients.

As expected, Magnet status was associated with better work conditions, probably because the Magnet hospital program emphasizes the importance of autonomy, decision-making participation, and coordination with other disciplines – our measures of work conditions. In addition, a pattern of rapid decreases in the number of hospital admissions was associated with poorer work conditions, perhaps because uncertainty about the meaning of such reductions in admissions, e.g. poor financial performance, possible hospital closure, was reflected in efforts to increase bureaucratic control over nurses work, and tensions across disciplines that led to less frequent and less meaningful collaboration. Higher levels of work complexity were associated with poorer work conditions suggesting that nurses faced with increased work complexity must focus on the immediacy of the day-to-day challenges in completing their work rather than on building environments that improve their autonomy, decision making and relational coordination capacities.

Patient satisfaction was higher on nursing units that had greater availability of support services and higher levels of work engagement. Because these support services generally assist in reducing time spent in non-direct care tasks, nurses are more able to spend time engaged in the cognitive tasks associated with autonomous practice, with participation in decision-making and in collaboration with other disciplines. Nurses employed in hospitals with better working conditions are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs, (12) which may lead them to exhibit higher levels of work engagement which in turn should lead to more satisfied patients.

Findings about patient demographics mirror results from other studies i.e. older and less sick patients are more highly satisfied. Further, our finding of a significant relationship between symptom management and patient satisfaction is important because this highlights the critical role that effective management of patient symptoms plays in determining their satisfaction. Nurse executives must be mindful that effective symptom management is important to patient satisfaction in medical surgical units and should assure that their systems of care are designed to meet these patient expectations.

Conclusion

Our study does have limitations. Even though we used random sampling to recruit patients, sampling bias remains a potential problem. Our patient sample, primarily female, and in self-rated good health, are those who tend to report higher levels of satisfaction. Thus our sample may have excluded patients who would have been likely to report lower levels of satisfaction. Further, we were unable to collect information about patients’ encounters with other areas of the hospital or clinical information, which might also affect patient satisfaction.

Despite these limitations, our study is one of only a few to examine whether organizational, nursing unit and patient characteristics influence patient satisfaction. In particular, our findings show that work engagement and availability of support services have a significant impact on patient satisfaction, a finding that should be considered by nurse executives in designing the best systems of care. Our findings also reinforce the importance of effective symptom management and the critical role that nursing care plays in achieving patient satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: National Institute of Nursing Research (National Institutes of Health).

Grant number 5R01NR003149 “A Model of Patient and Nursing Administration Outcomes;” National Institute for Nursing Research Grant number 5T32NR008856 “Research Training: Health Care Quality and Patient Outcomes.”

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.United States Department of Health & Human Services. [Accessed November 2, 2008];Hospital Compare - A quality tool for adults, including people with Medicare page. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov.

- 2.Jha A, Orav E, Zheng J, Epstein A. Patients’ perceptions of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young G, Meterko M, Desai K. Patient satisfaction with hospital care: Effects of demographic and institutional characteristics. Med Care. 2000;38:325–334. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson J, Chamberlin J, Kroeneke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott J, Sochalski J, Aiken L. Review of magnet hospital research: Findings and implications for professional nursing practice. J Nurs Adm. 1999;29:9–18. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mark B, Hughes L, Belyea M, et al. Does safety climate moderate the influence of staffing adequacy? and work conditions on nurse injuries? Journal of Safety Research. 2007;38(4):431–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mark B, Salyer J, Wan T. Professional nursing practice: Impact on organizational and patient outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33:224–234. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200304000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnetag S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between work and nonwork. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88:518–528. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soafer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larabee J, Ostrow C, Winthrow M, Janney M, Hobbs G, Burant C. Predictors of patient satisfaction with inpatient hospital nursing care. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:254–268. doi: 10.1002/nur.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue M, Piazza I, Griffin M, Dykes P, Fitzpatrick J. The relationship between nurses' perceptions of empowerment and patient satisfaction. Appl Nurs Res. 2008;21:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClure M, Poulin M, Sovie M, Wandelt M. Magnet hospitals: Attraction and retention of professional nurses. Kansas City: American Nurses Association; 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gittell J. Organizing work to support relational co-ordination. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2003;11:517–539. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark BA. A model of patient and nursing administration outcomes. Funded by NINR, Grant # 5RO1 NR003149. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overton P, Schneck R, Hazlett C. An empirical study of the technology of nursing subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1977;22:203–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mark B, Hagenmueller A. Technological and environmental characteristics of intensive care units: Implications for job re-design. J NursAdm. 1994;24(4S):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salyer J. Development and psychometric evaluation of an instrument to measure staff nurses’ perception of uncertainty in the hospital environment. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1978;4:33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCorkle R, Young K. Development of a symptom distress scale. Cancer Nursing. 1978;1:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minick P, Dilorio C, Mitchell P, Dudley C. The early recognition of patient problems: Developing an instrument reflecting nursing expertise. Working paper. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerber R. Control over nursing practice scale; Paper presented at the National Conference on Instrumentation in Nursing; September 4, 1990; Tuscon, AZ: University of Arizona; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mark B, Hagenmueller A. Technological and environmental characteristics of intensive care units: Implications for job re-design. J NursAdm. 1994;24:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gittell J, Fairfield K, Bierbaum B, et al. Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and functioning, and length of stay: A 9-hospital study of surgical patients. Med Care. 2000;38:807–819. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus user’s guide. 4th Ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]