Abstract

Background

We report the results of a longitudinal study of former child delinquents in Germany, stratified according to the number of offenses they committed before and after attaining the age of criminal responsibility (14 years).

Methods

A control group consisted of persons who had had no contact with the police as children. A total of 263 individuals aged 18 years and above (mean age, 22 years) were studied with a standardized personal interview about their life history, family, health, schooling, and vocational training, as well as an intelligence test (WIP), a personality questionnaire (FPI), and a questionnaire about parental child-rearing styles. They were also given a questionnaire developed especially for this study about delinquent activities before age 14 for which they had not been apprehended by the police. Data on their interactions with the law enforcement authorities were taken from their uncensored childhood and adult criminal records up to age 40.

Results

At the most recent data collection (1996), the subjects had reached a mean age of 42 years. They were classified into three groups: non-offenders, “persisters” (former child delinquents who continued to commit crimes), and “desisters” (former child delinquents who stopped committing crimes). Logistic regression analysis enabled the retrospective prediction of multiple delinquency in childhood and adolescence, as well as of delinquency over the course of life. The main prognostically relevant factors were the summated social and familial risk factors, followed by personality traits and the number of unregistered (self-reported) property offenses in childhood.

Conclusion

These findings show that early delinquency does not necessarily develop into a long-term criminal career, and that the risk factors for criminality are nearly the same as those for mental disturbances. Only three risk factors seem to be specific to criminality: male sex, the early onset of aggressiveness, and the negative influence of delinquent peers.

The term “child delinquency” refers to the commission of criminal offenses by minors. In Germany, the age of criminal responsibility begins on a person’s fourteenth birthday; thus, child delinquency in Germany is the commission of criminal offenses by children up to and including age 13. Such persons are excluded from criminal responsibility by the German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch, StGB; §19 StGB) and cannot be criminally prosecuted. The establishment of the fourteenth birthday as the onset of criminal responsibility is, admittedly, arbitrary.

In criminology and sociology, offenses against criminal norms are considered to be a subcategory of socially deviant behavior. Antisocial or dissocial behavior is said to be present only when the individual’s behavior offends against societal norms and the rights of other persons (1).

Deviation from a societal or legal norm cannot be equated with a mental disturbance. There is no special category for delinquency in either of the international classification systems for psychiatric disease, ICD-10 and DSM-IV.

In the ICD-10, criminal offenses are coded as “disturbances of social behavior” when they fulfill certain defined criteria, e.g., the use of a dangerous weapon, physical cruelty or violence against persons, destruction of the property of others, or arson.

Only recently has it become widely appreciated that many criminals suffer from mental disturbances and neuropsychological abnormalities which play a major role in the development of dissocial and delinquent behavior (2).

Epidemiology

Nearly all children commit offenses against the law, of varying type and severity, as part of the process of norm acquisition and growing into one’s place in society. Little is known about the true extent of such offenses, not least because only a very small number of them result in a complaint to the police, in consequence of the age and developmental state of the offenders. Children also tend to commit relatively minor offenses, with the exception of a small group who later develop into intensive offenders.

The epidemiological study of child delinquency generally relies on two data sources: police statistics on criminal activity, and attempts to collect information about offenses that were committed but did not result in a complaint to the police.

Police statistics, by their nature, deal with persons suspected of having committed an offense. Their usefulness in estimating the amount of actually occurring delinquency by minors is thus limited by multiple factors:

the public’s general reluctance to complain to the police about a child’s behavior;

the incomplete ascertainment of offenses;

the large number of cases that remain undetected;

major differences between regions.

Despite these limitations, police statistics are nevertheless used to study the development of criminality, for lack of more accurate data sources. Police statistics in Germany reveal a mild overall decline in child delinquency since 1988, but, over the same period, a marked increase in violent behavior (simple and aggravated assault).

Studies estimating the number of offenses committed by children that are never reported to the police have shown that criminal behavior in childhood is the rule, rather than the exception. Some 90% of children commit criminal offenses, mostly mild ones.

Prospective longitudinal studies have yielded the most useful information on this topic (3– 5). Their main finding is that delinquency is highly age-dependent: its incidence and prevalence rise continually into adolescence (approximately age 17 to 20) and fall rapidly thereafter (6). By age 28, about 85% of former law-breakers have stopped offending against the law (7). These findings and others provided the motivation for Moffitt’s (8) empirically based taxonomy of delinquent behavior, which distinguishes “life-course-persistent” from “adolescence-limited” delinquency. Lifelong delinquency, in Moffitt’s theoretical framework, arises as the combined result of two factors. The first factor is a behavioral disturbance in early childhood, such as attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), aggressiveness, or disturbances of social behavior, which limit the individual’s developmental possibilities. The second factor is the affected persons’ active seeking out of deleterious influences and living environments that make allowance for their deficits. In contrast, delinquency that begins during puberty and that remains restricted to adolescence (up to young adulthood) is thought to be a product of social-psychological and phase-specific precipitating factors.

Causes

There is no doubt that biological and psychosocial factors play a role in the causation of dissocial (antisocial) and delinquent behavior, and most of these factors can already be found in childhood (3, 4). The biological factors include, for example, abnormal autonomic responses and neuroendocrine disturbances; the psychosocial factors include a breakdown of normal family relationships, child abuse, and certain types of mental disturbance.

As a rule, the contributions of biological and psychosocial risk factors to the causation of dissocial and delinquent behavior are interactive, rather than merely additive. Thus, when a certain biological risk factor and a certain psychological risk factor are both present, the delinquency rate is markedly higher than the sum of the rates associated with each factor alone.

The risk factors are opposed by protective mechanisms that hinder the development of dissocial and delinquent behavior. Like the risk factors, these protective mechanisms act in a variety of ways and are operative at different times. They are not merely defined as the absence of risk factors; rather, they consist of independent traits and conditions that can be identified in the individual, in the family, and in the social environment. They include the following:

A favorable genetic predisposition, without relevant abnormalities or illnesses in the family

Normal reactivity of the autonomic nervous system

Above-average intelligence

Capacity for empathy

Scholastic and social success

A harmonious family atmosphere, with parents who are competent in child-rearing

Good familial and social conditions for personal development.

It would be wrong, however, to consider the occurrence of dissociality and/or delinquency merely as the result of an interplay of risk factors and protective factors. The onset, course, and termination of delinquent behavior are also influenced by individual decision processes, which, in turn, are affected by personal experiences and turning points in life history (3– 5).

The Marburg Juvenile Delinquency Study

Purpose and methods

The goal of this long-term study was to follow delinquent children in their further interactions with the law beyond the age of 40, and to derive predictive factors for delinquent behavior in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. A further goal was to follow the course of delinquent behavior over the person’s entire life span. The study was explicitly not intended to evaluate interventions or preventive measures.

The study included all boys who committed criminal offenses in the State Court District (Landgerichtsbezirk) of Marburg, Germany, from 1962 to 1971, and who reached the age of criminal responsibility (age 14) no later than in 1971 (n = 1006). This group of boys was stratified according to the number offenses registered by the police before and after they became 14 years old, and the group was then reduced in size by random sampling. The control groups consisted of subjects who had no contact with the police in childhood or adolescence (Group 0–0) and subjects who were registered as committing multiple offenses in adolescence, but not in childhood (Group 0–2) (0 = no offenses registered in childhood, 2 = at least 2 offenses registered in adolescence). The subjects in both of these control groups had, however, committed offenses that never became known to the police.

Details of the design and methods of this study can be found in the supplement accompanying this article (ebox) and in Remschmidt and Walter (4). The temporal course of the study is shown in Table 1, together with the composition of the study samples at Time Points 1 (1972), 2 (1975–77), and 3 (1996). In Table 2, detailed information is presented on how the group of 256 subjects came into being. The criminal records of these subjects were evaluated at Time Point 3 (register sample).

eBOX. Methods of the Marburg Juvenile Delinquency Study.

The initial study group included all boys who were registered as having committed criminal offenses in the Marburg State Court District from 1962 to 1971 and who had attained the age of criminal responsibility—i.e., had reached their fourteenth birthday—by 1971 (N = 1,006). This group was stratified according to the commission of crimes up to age 13 and from age 14 onward and reduced in size by random sampling. There were control groups consisting of subjects who had no contact with the police in their childhood (Group 0–0) and subjects who were registered as having committed offenses multiple times during their adolescence, but not in childhood (Group 0–2) (0 = never registered in childhood, 2 = registered multiple times in adolescence). Subjects in both of these control groups had committed offenses that remained unknown to the police. A total of 263 subjects were studied in the period 1975–77. They were then at least 18 years old (mean, 22 years). The subject dropout rate (rate of refusal to continue participation in the study) was 17% among all of the subjects (offenders and control subjects) who met the inclusion criteria for the study (n= 344). Of the remaining 283 subjects, 20 were excluded after corrections for group membership and parallelization of unregistered offenses committed before age 14. Thus, 263 subjects remained in the study.

The battery of instruments used in the study included:

-

A standardized interview to obtain information on life history

family

health

schooling

vocational training

An intelligence test (WIP)

A personality questionnaire (Freiburg Personality Inventory, FPI)

A questionnaire on parental child-rearing styles.

In addition, a specially constructed questionnaire was used to obtain information on offenses that were committed before the subjects reached age 14 and that remained unknown to the police (cf. Reference [9]). The methods used are described in greater detail in the authors’ monograph (4). The above tests were all carried out in the period 1975–77 by two project participants, a psychologist and a research assistant (cf. also Table 1). Unrestricted access to criminal records made it possible to follow the subjects’ further interactions with the judicial system up to age 40 and beyond. The last data acquisition was performed in 1996 (Time Point 3), at which time the subjects had attained an average age of 42 years. This study design enabled the subjects to be divided into three groups at Time Point 3, so that the predictive value of data acquired at Time Points 1 and 2 with respect to membership in these three groups could be retrospectively evaluated. The three groups were:

Subjects who committed no offenses coming to the attention of the police over the entire time of the study (n = 46; Group 0)

Offenders who committed no further offenses after Time Point 2, at which time the subjects had reached the average age of 22 years (n = 142; Group 2)

Chronic offenders, defined as subjects who committed offenses that were registered by the police both in childhood (Time Point 1) and in adolescence (up to age 22), and then committed at least two further offenses between Time Points 2 (mean age, 22 years) and 3 (mean age, 42 years) (n = 68; Group 3).

Table 1. The temporal course of the longitudinal study.

| Evaluation of documents from the prosecutor’s office | Individual assessment of subjects | Evaluation of educational and criminal records |

| n = 1758 children from the Marburg State Court District (Landgerichtsbezirk) with offenses registered by the police from 1962 to 1971 | n = 263 subjects age 18 and above with variable frequency of registered offenses before and after their 14th birthday, including two control groups: | n = 256 subjects who were assessed at Time Point 2 and were still alive at Time Point 3; 7 subjects died between 1977 and 1996 |

| ↓ |

|

Examination of the subjects’ criminal records when they had reached a mean age of 42 years revealed the following: |

| Reduced to n = 1006 boys who were under age 14 in 1971 |

|

|

| Stratification by police registration of offenses committed up to age 13 and from age 14 onward followed by random sampling, n = 283 | Instruments: | |

| 20 persons were excluded because they did not fulfill the parallelization criteria; thus, there were 263 subjects in the study. |

|

|

| 1972 | 1975 to 1977 | 1996 |

| Time Point 1 | Time Point 2 | Time Point 3 |

Table 2. Sample of subjects assessed individually at Time Point 2 (n = 263) and sample of subjects whose criminal records were evaluated at Time Point 3 (n = 256).

| Number of offenses committed up to age 13 | Number of offenses committed from age 14 onward | Total | |

| 0 | ≥ 2 | ||

| 0 | 47 (– 1) | 43 | 90 (– 1) |

| 1 | 48 (– 1) | 49 | 97 (– 1) |

| ≥ 2 | 32 | 44 (– 5) | 76 (– 5) |

| Total | 127 (– 2) | 136 (– 5) | 263 (– 7) = 256 |

The numbers in parentheses refer to subjects who died between Time Point 2 (1975–1977) and Time Point 3 (1996). 256 subjects were available for study at Time Point 3. Their criminal records were used to classify them into three groups based on long-term outcomes (cf. last column of Table 1)

Results

A main goal of this study was to find a way to predict the variable course of delinquent behavior from data acquired in a person’s childhood and adolescence. Doing this required making use of data on the subjects up to age 42 that were obtained from the Federal Central Registry (Bundeszentralregister, a nationwide registry of court records in Germany). Stepwise logistic regression—a statistical procedure that can be used without the need to formulate a specific hypothesis in advance—was applied to data pertaining to the subjects’ childhood, adolescence, and adulthood up to age 42. The following variables were taken into consideration:

Unregistered offenses committed up to age 13 (subdivided into property offenses and violent offenses)

The sum of psychosocial risk factors that were operative up to age 13

Physical health, including any type of developmental delay if present

Familial risk factors

Parental risk factors

Learning difficulties in school

Lack of vocational training, or premature termination of vocational training

Parental child-rearing style, as perceived by the child

Personality variables measured with the Freiburg Personality Inventory (FPI).

All variables relating to childhood were ascertained from 1975 to 1977, retrospectively in some cases. The mean age of the subjects at Time Point 2 was 22 years. The logistic regression analysis was based on an additive prediction model and enabled identification of the variables that significantly contributed to an improved prediction. At the same time, intercorrelations between predictors were eliminated.

Prediction of events occurring in childhood

Offenses committed in childhood that were registered by the police were, in general, not predictable on the basis of earlier data, except in the case of repeat offenders. The rate of correct classification was only 62.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 56.6%–68.4%; p = 0.05). The only factor contributing significantly to prediction was the variable “learning difficulty in school.”

Prediction of events occurring in adolescence

The probability of multiple offenses being registered by the police in adolescence (ages 14 to 22) rose to 71.5% (95% CI: 66%–77%, p = 0.05) when the unregistered offenses of persons of the same age were taken for comparison. The best single predictor was dropping out of school, followed by the sum of social and familial risk factors (up to age 13), maternal strictness, and the sum of unregistered property offenses up to age 13.

Prediction of events occurring up to age 42

With regard to the entire course of life up to age 42, the subjects could be separated into three groups:

persons who never committed offenses that were registered by the police (“non-offenders”),

chronic offenders (“persisters”),

offenders whose delinquency was temporally limited (“desisters”).

Persons in the last category committed no further offenses after age 22 (mean age). Data regarding events occurring in adulthood were obtainable only from the Federal Central Registry and were acquired when the subjects had reached a mean age of 42 years. On the basis of these data, we studied whether one could predict which of the three abovementioned groups a subject would eventually belong to, and, if so, which variables could be used to make this prediction.

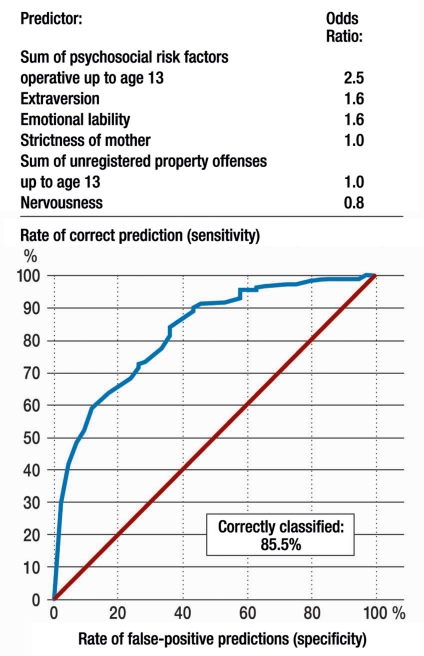

First, we compared the group of persons who committed no offenses coming to the attention of the police in their entire lifetimes (n = 46) with the overall group of offenders (n = 210). As seen in the Figure, 85.5% of subjects were correctly classified (95% CI: 81.2%–89.8%, p = 0.05). The sum of psychosocial risk factors, e.g., alcoholism in a parent, being raised in a children’s home up to age 5, parental separation/divorce, or dropping out of school, had the highest predictive value, with an odds ratio of 2.5. The variables “maternal strictness” (a strict child-rearing style of the mother, as perceived subjectively by the child) and “sum of unregistered property offenses up to age 13” also retained their predictive value. Among the personality variables, three were found to have predictive value:

Figure.

Results of stepwise logistic regression analysis: long-term comparison of subjects without any registered offenses (n=46) and subjects with registered offenses (n=210) (From: Remschmidt H, Walter R: Kinderdelinquenz. Gesetzesverstöße Straf-unmündiger und ihre Folgen. Heidelberg: Springer 2009. Reprinted with the kind permission of Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg.)

Extraversion

Emotional lability

Nervousness.

A pairwise comparison of the three groups of subjects yielded the results displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Results of stepwise logistic regression analyses: long-term comparison of subjects with no registered offenses (n = 46), chronic offenders (n = 68), and non-chronic offenders (n = 42).

| Comparison | Correctly classified (%)* | Predictors | Odds Ratio | |

| Subjects with no registered offenses versus chronic offenders | 80.2 | – | Sum of social and familial risk factors that were operative up to age 13 | 3.0 |

| (73.2–87.2) | ||||

| – | Extraversion | 1.6 | ||

| – | Emotional lability | 1.5 | ||

| – | Sum of unregistered property offenses up to age 13 | 1.0 | ||

| Subjects with no registered offenses versus non-chronic offenders | 77.9 | – | Sum of psychosocial risk factors that were operative up to age 13 | 1.9 |

| (72.0–83.8) | ||||

| – | Spontaneous aggressiveness | 1.4 | ||

| – | Extraversion | 1.3 | ||

| Non-chronic versus chronic offenders | 73.1 | – | Problems in school | 2.5 |

| (67.1–79.1) | – | Depressivity | 1.3 | |

* The figures in parentheses are the 95% confidence intervals for the percentages given

The most predictable condition was the chronic offender state (rate of correct classifications: 80.9%), followed by the desister state (77.9%), both compared to persons without any registered offenses. The rate of correct classification of chronic offenders compared to desisters was 73.1%.

When all offenders were combined into a single group and compared to non-offenders, the rate of correct classifications was 85.5%. In three of four group comparisons, the sum of social and familial risk factors was the best predictor. This sum failed to have predictive value only for distinguishing persisters from desisters.

All long-term (lifelong) prognoses were found to depend to a significant extent on personality traits; these were generally the second most important predictive factor, after the sum of social and familial risk factors. The personality traits in question were, in particular: extraversion, emotional lability, nervousness, and spontaneous aggressiveness. The more pronounced any of these traits was, the higher the risk of delinquency.

Earlier versus later onset of delinquency

A comparison of subjects who first committed offenses that became known to the police before or after attaining the age of criminal responsibility, i.e., before or after their 14th birthday (early onset, n=96; late onset, n=43) showed that those who became delinquent later were more aggressive (both reactively and spontaneously), more depressive, and more emotionally labile than those who became delinquent earlier. Persons whose delinquency was restricted to childhood were not included in this comparison.

The effect of protective factors

In order to identify the variables that protect against delinquency, we looked at subjects whose risk factors predicted that they were likely to become delinquent, and we compared those who committed at least two offenses with those who remained resilient, i.e., committed only one offense or none at all despite their risk factors. For this purpose, high-risk subjects were defined as those with two or more psychosocial risk factors. The comparison was based on 32 subjects who committed at most one offense up to age 14 and 117 subjects who committed at least two offenses over the course of their lives. We found that the criminally resilient subjects had committed fewer unregistered offenses up to age 13; thus, they were more norm-oriented and socially adapted. Moreover, they were less aggressive (both reactively and spontaneously), less depressed, less excitable, and less emotionally labile. Overall, they were more emotionally stable and balanced. No features of parental child-rearing style (strictness or supportiveness of either father or mother) exerted any protective effect.

Discussion

The results presented here with regard to long-term course support the empirically based taxonomy of Moffitt (8) in that they allow the identification of two different types of delinquents, namely, chronic delinquents and those whose delinquency is temporally limited. We were, however, unable to show any consistent relationship between this typology and the early or late onset of delinquency. Offenses committed in childhood, whether known to the police or not, had no effect on the later (chronic) course of delinquency. We, the authors of this article, think that the Moffitt taxonomy needs to be revised and made more precise, as has already been proposed by others (10, 11). An earlier onset of delinquency need not lead to a chronic criminal career, and, conversely, not all chronic offenders were already delinquent or dissocial in childhood (4, 12).

It remains less than fully clear whether the risk factors identified in this and other longitudinal studies are specific for the development of delinquency or might also predict other deviations from the norm, such as mental illness, alcoholism, and drug abuse. The current, provisional state of knowledge seems more compatible with the latter possibility (13, 14). Up to the present time, only three variables have been found to predict delinquency specifically, and not any other of the types of deviation just mentioned: male sex, aggressiveness as a trait, and the negative influence of delinquent friends (15).

In the present study, other personality traits besides aggressiveness were found among the risk factors as well as among the protective factors. Their effect on prediction cannot be attributed to the influence of familial and social factors, because this was eliminated by statistical methods. Moreover, in the overall group of subjects, no correlation was found between personality traits on the one hand, and social and familial factors on the other. These factors had no effect on traits such as emotional lability, nervousness, aggressiveness, or depressiveness. Personality traits thus take on greater importance, and it seems that more attention should be paid to them with a view toward prevention (training of pro-social behavior). The opportunities to alter social and familial risk factors are limited in any case.

Limitations

The goal of this study was not to acquire epidemiological data covering a broad segment of the population, but rather to illuminate the course of early-onset delinquent behavior. Therefore, we did not employ an unselected sample that would have been representative of children as a whole. It follows that we cannot draw any conclusions about non-delinquent abnormalities, which would be beyond the scope of the study methods that we applied. The sample was, however, representative of the children who were found to have committed offenses during the period of data acquisition. It was derived by random sampling of this overall group. Furthermore, the study sample was drawn from a mainly rural area of Germany, and the conclusions reached cannot necessarily be extrapolated to urban centers. Lastly, it should be remembered that the socioeconomic conditions under which the subjects grew up have changed markedly over the last two decades. Nonetheless, we still find it striking that, when the results presented here are compared with those of other studies performed abroad, with different methods, and on different study samples, the similarities turn out to be far more pronounced than the differences.

Key Messages.

Children who have not yet reached the age of criminal responsibility already commit criminal offenses that are registered in police crime statistics; such statistics, by their nature, have to do with the suspicion that a particular person has committed a crime. The amount of child delinquency that is committed, but remains unknown to the police, can be estimated with the aid of suitable questioning techniques.

Although the overall number of offenses committed by children has gone down since 1988, police crime statistics show a continuous rise in the number of violent offenses (simple and aggravated assault) over the same time period, and also, to a lesser extent and with temporal fluctuations, a rise in the number of robberies.

Factors playing a causal role in child delinquency include biological factors (e.g., abnormal autonomic responses, neuropsychological abnormalities), psychological factors (e.g., mildly low intelligence, developmental disturbances, an unfavorable social environment), mental disturbances (e.g., attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], disturbances of social behavior), and situational influences (e.g., opportunities to commit offenses, group influence, access to weapons).

Longitudinal studies reveal that the course of delinquency is highly age-dependent, and that two types of cousrse can be distinguished: time-limited delinquency and persistent delinquency. Most criminal offenses committed by children and adolescents fall into the first category, while the second category comprises 5% to 7% of all male criminals and consists of former child delinquents who persist in committing crimes (often, violent ones) in adulthood. To a certain, restricted extent, this development can be predicted on the basis of psychosocial traits and biographical stress factors.

This study and other, similar ones also show that child delinquency need not be the prelude to a lifelong criminal career. Such a career can be triggered, however, by social and familial risk factors, by certain personality traits, and, to some extent, by the person’s having committed a large number of offenses in childhood that did not come to the attention of the police.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

This study was supported for many years by the German Research Foundation.

We thank Dipl.-Math. Dr. Cornelius Gutenbrunner for the statistical evaluation of data and Dipl.-Psych. Jürgen Schönberger for the preparation of the graphic elements. We also thank the directorate of the Federal Ministry of Justice for permission to use excerpts from the Federal Central Registry (a registry of criminal records).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Hinshaw SP, Zupan BA. Assessment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behaviour. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeiren R. Psychopathology and neu-ropsychological deficits in delinquent adolescents. Antwerpen: Universiteit Antwerpen; 2002. Delinquents disordered? [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Child delinquence. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remschmidt H, Walter R. Gesetzesverstöße Strafunmündiger und ihre Folgen. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009. Kinderdelinquenz. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boers K, Loesel F, Remschmidt H, editors. Entwicklungskriminologie und kriminologische Lebenslaufforschung. MschrKrim. 2009;(Sonderheft 2/3) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tolan PH, Thomas P. The implications of age of onset for delinquency risk. II. Longitudinal data. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;23:157–181. doi: 10.1007/BF01447087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrington DP. Stepping stones to adult criminal careers. In: Olweus D, Block J, Radke-Yarrow M, editors. Development of antisocial and prosocial behaviour. London-New York: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 359–384. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: adevelopmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remschmidt H, Merschmann W, Walter R. Zum Dunkelfeld kindlicher Delinquenz. Eine Erhebung an 483 Probanden. MschKrim. 1975;58:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albrecht H-J, Grundies V. Justizielle Registrierungen in Abhängigkeit vom Alter. Befunde aus der Freiburger Kohortenstudie. MschKrim. 2009;91(2/3):326–343. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kratzer L, Hodgins S. A typology of offenders: A test of Moffitt’s theory among males and females from childhood to age 20. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1999;9:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson GR, Forgatch MS, Yoerger KL, Stoolmiller M. Variables that initiate and maintain an early-onset trajectory for juvenile offending. Developmental Psychopathology. 1998;10:531–547. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lawton JM. Vulnerability to childhood problems and family social background. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1990;31:1145–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werner EE. Antecedents and consequences of deviant behavior. In: Hurrelmann K, et al., editors. Health hazards in adolescence. Prevention and intervention in childhood and adolescence. Berlin: De Gruyter; 1990. pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roff JD, Wirt RD. The specifity of childhood problem behavior for adolescent and young adult maladjustment. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1985;41:564–571. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198507)41:4<564::aid-jclp2270410420>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]