Abstract

Chemotaxis and integrin activation are essential processes for neutrophil transmigration in response to injury. CalDAG-GEFI plays a key role in the activation of β1, β2, and β3 integrins in platelets and neutrophils by exchanging a GDP for a GTP on Rap1. Here, we explored the role of CalDAG-GEFI and Rap1b in integrin-independent neutrophil chemotaxis. In a transwell assay, CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils had a 46% reduction in transmigration compared with WT in response to a low concentration of LTB4. Visualization of migrating neutrophils in the presence of 10 mM EDTA revealed that CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils had abnormal chemotactic behavior compared with WT neutrophils, including reduced speed and directionality. Interestingly, Rap1b−/− neutrophils had a similar phenotype in this assay, suggesting that CalDAG-GEFI may be acting through Rap1b. We investigated whether the deficit in integrin-independent chemotaxis in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils could be explained by defective cytoskeleton rearrangement. Indeed, we found that CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils had reduced formation of F-actin pseudopodia after LTB4 stimulation, suggesting that they have a defect in polarization. Overall, our studies show that CalDAG-GEFI helps regulate neutrophil chemotaxis, independent of its established role in integrin activation, through a mechanism that involves actin cytoskeleton and cellular polarization.

Keywords: Rap1, adhesion, F-actin, polarization

Introduction

Neutrophil chemotaxis and transmigration toward a source of inflammation are two crucial processes for host defense against infection. Circulating neutrophils respond to a variety of inflammatory stimuli such as cytokines, chemokines, and LTs [1,2,3]. Through a multi-step process, neutrophils first roll on the activated endothelium via a mechanism that depends on P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 on the neutrophil and selectins on the endothelium [4]. Rolling leukocytes on the endothelium become activated [5, 6]. In this process, integrins on their surface transition from a low-affinity state that does not allow ligand binding to a high-affinity state that does allow ligand binding [7]. Integrins in the high-affinity conformation allow leukocyte firm adhesion to the endothelium. Finally, the neutrophil transmigrates into the tissue, where it migrates to the site of tissue injury or infection.

Although neutrophil adhesion to the inflamed endothelium is dependent on integrin function [4, 8], several authors have shown that cell migration is also possible in the absence of functional integrins. Neutrophils have been shown to chemotactically migrate in the presence of EDTA and blocking antibodies against β1 and αVβ3 [9]. In addition, neutrophils from a patient with leukocyte adhesion deficiency type-I (lacking β2 integrins) were also able to polarize and chemotax [10]. More recently, Lammermann and colleagues [11] showed that dendritic cells lacking all integrins on their surface were able to migrate to the lymphatic nodes when injected into the dermis, revealing that integrin-independent migration is not restricted to in vitro experimental settings but can also occur in vivo.

CalDAG-GEFI is a signaling molecule that in response to calcium and diacylglycerol, activates the small GTPase Rap1 by exchanging a GDP for a GTP [12]. Its expression is restricted to the basal ganglia and blood cells [12]. In platelets and neutrophils, CalDAG-GEFI is required for integrin activation [13, 14], and in human T cells, it is needed for LFA-1-mediated adhesion [15]. As a result, mice lacking CalDAG-GEFI present impaired inflammatory responses as a result of reduced leukocyte infiltration into the inflamed tissues and deficient platelet aggregation manifested as bleeding [13, 14]. Rap1 proteins are GTPases of the Ras family broadly expressed in tissues. There are two isoforms of Rap1: Rap1a and Rap1b. Rap1b is the major isoform in platelets [16], B cells [17], and neutrophils [18], and Rap1b−/− mice show a bleeding phenotype and impaired integrin activation similar to that of CalDAG-GEFI-deficient mice [19].

We were interested in examining whether CalDAG-GEFI may have biological activities other than integrin activation. Here, we report that CalDAG-GEFI plays a role in neutrophil chemotaxis, independent of integrin function, by a mechanism that involves F-actin distribution and cell polarization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Six- to eight-week-old C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). CalDAG-GEFI−/− [13] and CD18−/− [20] mice were bred and housed in our animal facility. Rap1b−/− mice [19] and their WT controls were on a mixed background and obtained from the Blood Research Institute, Blood Center of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI, USA). Experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the Immune Disease Institute and Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA, USA).

Neutrophil isolation

Mouse neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow by negative immunoselection as described [14]. Bone marrow cells were incubated with a cocktail of rat anti-mouse mAb against non-neutrophil cell markers, followed by a second incubation with anti-rat IgG coupled to magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). The cells were run through a magnetic column (Miltenyi Biotec) and the eluted neutrophils counted by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Only samples with >90% of neutrophils were used.

Transwell migration assay

Neutrophils (105) in RPMI 1640 + 10 mM HEPES + 0.5% BSA (all from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) were placed in the upper well of a 12-transwell plate (Corning Inc., Acton, MA, USA). Different concentrations of LTB4 (Sigma Chemical Co.) or medium alone were placed in the lower well, and the system was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Neutrophils that transmigrated into the lower well were counted by flow cytometry. In some experiments, EDTA (10 mM) or a β2-integrin-blocking antibody (GAME-46, 10 μg/mL; BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) or CytoD (10 μM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was added to the cell suspension 10 min before starting the experiment.

Adhesion assay

Neutrophils (105) in RPMI 1640 with 10 mM HEPES and 0.5% BSA were loaded into a 24-well plate in the presence or absence of 10 mM EDTA and were activated or not with 10 ng/mL LTB4. Cells were let to adhere 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After washing twice with PBS, adherent neutrophils were counted using light microscopy.

Chemotaxis assay

Neutrophils were subjected to horizontal chemotaxis using the EZ-TAXIScan apparatus [21, 22] (Effector Cell Institute, Tokyo, Japan). Between 70 and 100 neutrophils in RPMI 1640 + 10 mM HEPES + 0.1% BSA + 10 mM EDTA were aligned on one edge of the chemotaxis channel. At the other end, 1 pg LTB4 was injected, creating a gradient along the channel. Pictures were taken every 30 s for 20 min, and recorded movies were analyzed using DIAS (Soll Technologies Inc., Iowa City, IA, USA).

F-actin quantification by flow cytometry

Neutrophils in suspension (105) were incubated for 10 min with 10 mM EDTA and stimulated with 0.1 ng/mL LTB4 for 30, 60, 180, or 300 s. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformadehyde. Unstimulated cells (Time 0) received the same volume of PBS and were fixed immediately. Cells were permeabilized and stained with 0.1% Triton X-100 and Alexa 488 phalloidin (6.6 nM; Molecular Probes). Mean fluorescent intensity of phalloidin-stained neutrophils was measured by flow cytometry.

F-actin staining and visualization

Isolated neutrophils (105) were incubated with 10 mM EDTA for 10 min and stimulated in suspension with 0.1 ng/mL LTB4 for 30 s. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeablilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with Alexa 488 phalloidin (6.6 nM) and Hoechst (1 μg/mL). Cells were observed in wide-field fluorescence microscopy (100×). Neutrophils with pseudopods with a width and length that exceeded 10% of the cell’s diameter were counted by two individuals blinded to their source.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± sem. Student’s t-test was performed, and results were considered to be statistically significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils have an integrin-independent defect in chemotactic transmigration

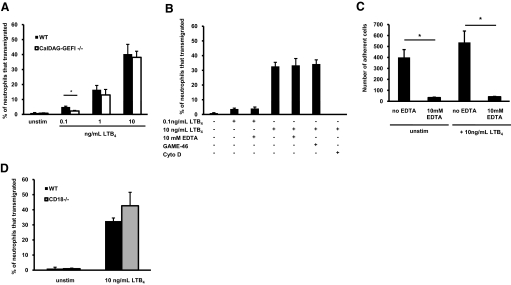

To reach a site of inflammation or infection, neutrophils have to adhere to the inflamed endothelium, transmigrate through endothelial cells, and chemotax through the extravascular tissue matrix toward the focus of inflammation [8]. Although integrins are critical for the adhesion of neutrophils to activated endothelium, their role in chemotaxis through the extravascular space is less understood. CalDAG-GEFI is a small signaling molecule that has been shown to play a key role in integrin activation by activating the small GTPase Rap1 [12]. Here, we show that CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils, whose only known phenotype is defective integrin activation, present impaired chemotaxis in integrin-independent assays as compared with WT neutrophils. In a transwell assay, WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils transmigrated toward LTB4 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). When no LTB4 was added to the medium (unstimulated) only 1% of WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils transmigrated into the lower well. Increasing concentrations of LTB4 resulted in increased numbers of transmigrated neutrophils. At high LTB4 concentrations, the percentage of WT neutrophils that transmigrated was similar to CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils but was higher at the lowest concentration of LTB4 (0.1 ng/mL; 5±0.5% WT vs. 2±0.4% CalDAG-GEFI−/−; P<0.05).

Figure 1.

Integrin-independent chemotaxis by mouse neutrophils. Defect in CalDAG-GEFI deficiency. (A) Percentage of neutrophils that transmigrated toward increasing concentrations of LTB4 in the transwell assay (n=4–11). (B) Percentage of WT neutrophils that transmigrated in the transwell assay in response to 0.1 or 10 ng/ml LTB4. Neutrophils were incubated with 10 mM EDTA, 10 μm/mL blocking β2 antibody (GAME-46), or 10 μM CytoD (n=3–6). (C) Adherent neutrophils on plastic after 1 h at 37°C, in the presence or absence of 10 mM EDTA. Cells were stimulated or not with 10 ng/mL LTB4 (n=3). (D) Transmigration of WT and CD18−/− neutrophils in the transwell assay (n=4); *, P < 0.05. Results represent mean ± sem. unstim, Unstimulated.

The fact that CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils were able to transmigrate in the transwell assay, despite a prominent defect in integrin activation [14], suggested that integrin function is not required in the transwell assay. To confirm this hypothesis, we used two approaches to interfere with integrins in the transwell assay. First, WT neutrophils were treated 10 min before starting the experiment with a β2-blocking antibody (GAME-46) or 10 mM EDTA. WT neutrophils stimulated with 0.1 or 10 ng/mL LTB4 were able to transmigrate into the lower well when 10 mM EDTA was used. Addition of a β2-blocking antibody did not affect the ability of WT neutrophils to transmigrate toward 10 ng/mL LTB4. These results suggest that integrin function was not required for transmigration (Fig. 1B). In contrast, CytoD, an actin polymerization inhibitor, abolished neutrophil transmigration completely (Fig. 1B). We confirmed that 10 mM EDTA inhibits neutrophil integrins by performing adhesion assays on plastic in the presence and absence of 10 mM EDTA, and little neutrophil adhesion was seen when EDTA was used (Fig. 1C). To confirm further that integrins were not required for transmigration in the transwell assay, we subjected CD18−/− neutrophils (lacking β2 integrins) to the transwell assay and compared them with WT neutrophils. LTB4 stimulation induced transmigration of CD18−/− neutrophils (42±8.9% neutrophils transmigrated), which was comparable with WT-transmigrated neutrophils (32±2.0%; P>0.05; Fig. 1D).

Our results are consistent with other studies showing that neutrophil chemotaxis and migration on nonendothelial surfaces can occur independently of integrin function [9,10,11, 23]. In vitro studies showed that CD4+ T cells were able to migrate in a collagen matrix even when β1, β2, β3, and αυ integrins were blocked [23]. In vivo studies showed that dendritic cells, in which all of their integrins were genetically ablated from their surface, were able to migrate to lymph nodes when injected into the dermis of a mouse. However, they could not migrate if they were injected into the circulation, a process that would require adhesion of the cells to the endothelium via integrins [11]. This study also showed that cell migration within a three-dimensional matrix is mediated through actin flow at the front of the cell and actomyosin contraction at the back, squeezing the cell within the scaffold of the matrix [11].

Impaired horizontal chemotaxis in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils (integrin-independent)

To study further the defect of CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils in chemotaxis, we used the EZ-TAXIScan apparatus that allows real-time visualization of neutrophil movement toward a source of chemoattractant on a horizontal glass surface. In these assays, neutrophils were aligned to one edge of the glass surface, and the chemoattractant was deposited on the other edge of the channel, creating a gradient of chemoattractant in the channel. To focus on neutrophil chemotaxis, independent of integrins, we used 10 mM EDTA in all buffers and cell suspensions. Because in the transwell assay, we saw the defect in transmigration at a low concentration of LTB4, we tested different concentrations of LTB4 and used 1 pg LTB4 (1 μL from a 1 ng/mL LTB4 solution), as it was the lowest concentration that induced chemotaxis (data not shown). The results revealed that WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils were able to migrate toward the gradient LTB4, showing again that neutrophil chemotaxis is possible in the absence of integrin function.

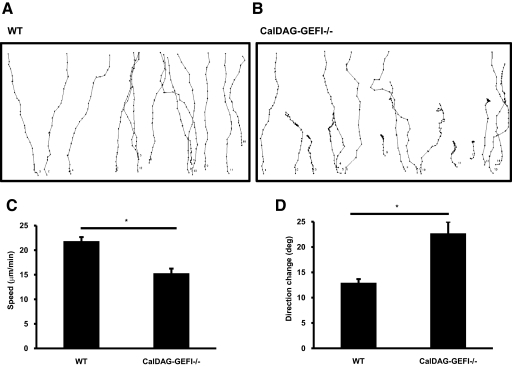

Using DIAS, we analyzed the migration characteristics of WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. Single cells were tracked, and their paths were analyzed (Fig. 2, A and B). We saw that the chemotactic defect observed in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils could be explained by significant abnormalities in their chemotactic behavior. First, CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils had slower migration speed compared with WT neutrophils (15±0.9 μm/s CalDAG-GEFI−/− vs. 22±0.8 μm/s WT; P<0.05; Fig. 2C). Second, CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils exhibited increased direction change (13±0.7° WT vs. 23±2° CalDAG-GEFI−/−; P<0.05; Fig. 2D). The direction change is a parameter that measures, in degrees, the number and frequency of turns a cell makes. A higher number indicates more turns and thus, less efficient chemotaxis. Third, CalDAG-GEFI−/−neutrophils had a reduced directionality index (Table 1). The directionality index indicates how straight a cell moves from point A to point B. It represents the minimum distance between A to B divided by the actual distance the cell migrated. Therefore, the straighter the cell migrates, the closer its directionality index will be to 1 and more efficient chemotaxis. Lastly, CalDAG-GEFI−/−neutrophils showed reduced upward directionality (Table 1). This parameter is the ratio between the distance moved in the direction of the chemoattractant and the real distance moved. It indicates how straight the cell goes from its starting point to the source of chemoattractant. In summary, CalDAG-GEFI−/−neutrophils present an overall defective chemotaxis compared with WT neutrophils. CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils are slower, make unnecessary turns, are less apt to migrate in a straight line, and do not move in the direction of the source of chemoattractant as efficiently as WT neutrophils. Thus, CalDAG-GEFI facilitates neutrophil migration toward LTB4 and this, in the absence of integrin-mediated adhesion.

Figure 2.

Impaired chemotaxis in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. (A and B) WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophil paths in response to a gradient of LTB4 in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. Paths shown are from one experiment representative of three independent experiments. (C) Speed (in μm/min) of WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. (D) Direction change of chemotactic neutrophils in degrees. Results are expressed in mean ± sem of 15–20 cells, each from three different movie sequences; *, P < 0.05.

TABLE 1.

Impaired Directionality in CalDAG-GEFI–/– Neutrophils

| WT (mean±sem) | CalDAG-GEFI–/– (mean±sem) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Directionality index | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | <0.05 |

| Upward directionality | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | <0.05 |

Impaired pseudopod formation and F-actin distribution in stimulated CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils

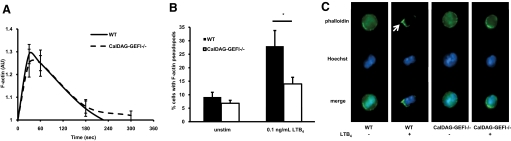

Our group has shown previously that CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils sense LTB4 normally, as measured by calcium flux after stimulation [14], suggesting that intracellular signaling immediately downstream of the LTB4 receptor is normal in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. Cytoskeleton rearrangement and in particular, F-actin polymerization and distribution are crucial processes for correct neutrophil chemotaxis. Indeed, blocking F-actin polymerization with CytoD resulted in abolished neutrophil transmigration in the transwell assay (Fig. 1B). We therefore wondered whether loss of CalDAG-GEFI could be affecting the actin cytoskeleton in response to LTB4. To address this question, we stimulated WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils and measured total F-actin polymerization by flow cytometry. As in the previous experiments, we used a low concentration of LTB4 (0.1 ng/mL), and to assure an integrin-independent environment, we stimulated neutrophils in suspension in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/−-unstimulated neutrophils (Time 0) did not show any change in their F-actin levels, but addition of 0.1 ng/mL LTB4 produced a rapid increase in F-actin in both genotypes (Fig. 3A). WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils showed similar kinetics of F-actin polymerization, reaching a peak after 30 s and decreasing rapidly after 1 min (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that CalDAG-GEFI is not required for total F-actin polymerization.

Figure 3.

F-actin polymerization and distribution in WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. Neutrophils in suspension containing 10 mM EDTA were stimulated or not with 0.1 ng/mL LTB4. (A) Kinetics of F-actin polymerization. Mean fluorescence intensity as measured by flow cytometry of F-actin staining with phalloidin was normalized to unstimulated cells for the time-points shown. Results represent mean ± sem (n=5–12). (B) Quantification of the percentage of neutrophils with F-actin-positive pseudopods. Neutrophils with pseudopods with a width and length that exceeded 10% of the cell’s diameter were counted. Results represent mean ± sem (n=6); *, P < 0.05. (C) Representative photographs of the cellular distribution of F-actin (phalloidin green) in WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils with (+) and without (–) LTB4 stimulation. Nuclear staining is in blue (Hoechst). Arrow indicates a pseudopod.

Because of the chemotactic defects in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils, we next wished to assess if there were any differences in the cellular distribution of F-actin upon stimulation. Neutrophils stimulated as described above were stained with phalloidin green, and F-actin distribution in individual cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Unstimulated WT neutrophils were round with uniform F-actin staining throughout the cytoplasm. Addition of LTB4 induced cell polarization with pseudopod formation and redistribution of the F-actin to the pseudopods in 28 ± 6% of the WT cells. In contrast, only 14 ± 2% of CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils formed pseudopods with F-actin after stimulation (P<0.05; Fig. 3B). Those neutrophils that did not respond to LTB4 showed a round morphology and uniform F-actin distribution in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 3C).

These results suggest that the defective chemotaxis seen in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils (a lower speed and defective chemotactic directionality compared with WT neutrophils) is likely a result of impaired cell polarization and defective F-actin localization at the pseudopods upon LTB4 stimulation, although their total F-actin polymerization is normal.

Impaired chemotaxis in Rap1b−/− neutrophils

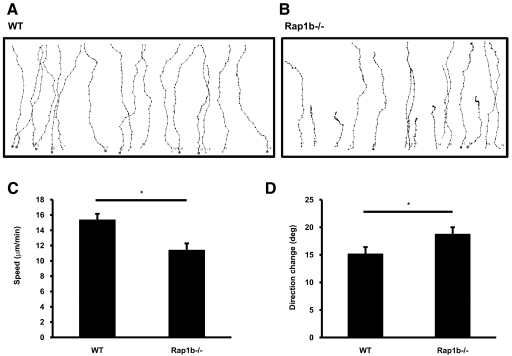

Small GTPases such as Rac, RhoA, and Cdc42 have emerged as key regulators of cell polarization by controlling formation of lamellipodia at the front of the cell (Rac) [24], organizing the actomyosin meshwork (RhoA) [25] or establishing cell polarity directly (Cdc42) [26]. In a recent study, depletion of Cdc42 in dendritic cells resulted in impaired chemotaxis and abnormal cytoskeleton organization with normal actin polymerization [27]. This phenotype highly resembles the chemotactic phenotype of CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils, suggesting that there could be a possible link between CalDAG-GEFI and Cdc42. In neurons, Rap1b was shown to activate Cdc42 regulating axon specification and neuronal polarity [28]. Interestingly, CalDAG-GEFI is highly expressed in neurons of the basal ganglia [12, 29], and it is known to activate Rap1 in platelets and neutrophils [12, 14]. In platelets, Rap1b rapidly incorporates into the cytoskeleton upon activation [30]. Therefore, we wondered whether the signaling pathway CalDAG-GEFI uses to regulate chemotaxis in neutrophils is through Rap1b. Rap1b−/− neutrophils and their respective WT control neutrophils were subjected to horizontal chemotaxis using the EZ-TAXIScan apparatus in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. WT and Rap1b−/− neutrophils sensed and migrated toward the gradient of LTB4 (Fig. 4, A and B). Rap1b−/− neutrophils presented reduced speed when compared with WT neutrophils (15±0.8 μm/s WT vs. 11±0.9 μm/s Rap1b−/−; P<0.05; Fig. 4C), and their direction change was higher than WT neutrophils (15±1.3° WT vs. 19±1.3° Rap1b−/−; P<0.05; Fig. 4D). On the other hand, the directionality index and upward directionality were similar in Rap1b−/− and WT neutrophils (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Impaired chemotaxis in Rap1b−/− neutrophils. (A and B) WT and Rap1b−/− neutrophil paths in response to a gradient of LTB4 in the presence of 10 mM EDTA using the EZ-TAXIScan apparatus. Paths shown from one experiment are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Speed (in μm/min) of WT and Rap1b−/− neutrophils. (D) Direction change (in degrees) of chemotactic cells. Results are expressed in mean ± sem of 16 cells, each from three different movie sequences; *, P < 0.05.

These results show that Rap1b−/− neutrophils present some degree of impaired chemotaxis. Although these results cannot be compared directly with the results obtained with CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils, as CalDAG-GEFI−/− and Rap1b−/− mice were on a different genetic background, the defect observed in Rap1b−/− neutrophils was reminiscent of that seen in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. Considering these similarities, we propose that CalDAG-GEFI is controlling neutrophil integrin-independent chemotaxis, at least in part, by a mechanism involving Rap1b. The fact that CalDAG-GEFI is expressed in neurons and that Rap1b is known to have a role in establishing neuron polarity suggests that CalDAG-GEFI could also be involved in the regulation of neuron polarity, but to the best of our knowledge, this has not been investigated.

Increasing concentrations of LTB4 rescued the defect of CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils in the transwell assay (Fig. 1A) and also in the horizontal chemotaxis (not shown), suggesting that alternative pathways may exist in the regulation of neutrophil chemotaxis. Interestingly, increasing concentrations of the agonist overcame the defect in Rap1 activation in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils [14], and protein kinase C signaling has been proposed as an alternative signaling pathway for integrin activation in CalDAG-GEFI−/− platelets [31]. Throughout our studies, we used concentrations of LTB4 of 1 or 0.1 ng/mL, as these were the concentrations where a major defect in neutrophil chemotaxis was seen in CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils. We believe these concentrations are biologically relevant, as they are in the concentration range described in inflammatory diseases, for example, in the synovial fluid of rheumatoid arthritis [32] or in the sputum of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [33].

Although our results strongly support the existence of integrin-independent migration of neutrophils [9, 10], the exact mechanism these cells use to migrate is not known. In the EZ-TAXIScan machine, the depth of the channel through which the neutrophils migrate is 4 μm, meaning that the neutrophils, averaging 10–12 μm in diameter, have to squeeze in between the upper and lower surfaces of the channel. A similar setting was used by Malawista and de Boisfleury Chevance [9], where human neutrophils were located between a glass coverslip and a glass slide, separated by 5.7 μm. Here, they showed that human neutrophil chemotaxis is possible, even in the presence of 10 mM EDTA or blocking antibodies to β1 and αVβ3 integrins [9]. In addition, neutrophils from a patient with leukocyte adhesion deficiency I (lacking β2 integrins), similar to the mouse β2-integrin-deficient neutrophils, underwent chemotaxis [9, 10]. The authors called this type of movement “chimney” and suggest that like a rock climber in a chimney, the cells use the contact with the surfaces as a force to locomote, minimizing the need for adhesion molecules. This is probably the same strategy WT and CalDAG-GEFI−/− neutrophils used to migrate in the channel of the EZ-TAXIScan chamber. However, the exact mechanism the cells use to migrate in these confined environments is still unknown. Hawkins et al. [34] proposed a mathematical model in which the cell migration in a channel relies on the coupling of actin polymerization to geometric confinement without the need for specific adhesion points. This model would be in accordance with our studies that suggest that the actin cytoskeleton directs cell movement when no integrin function is present. Indeed, Renkawitz and coworkers [35] documented recently that integrin-independent migration of ameboid dendritic cells is the result of retrograde flow of the actin filaments and accelerated actin polymerization at the leading edge. This mechanism maintains constant membrane protrusion and migration velocity of the cells [35]. It remains to be defined exactly how CalDAG-GEFI and Rap1 regulate this type of integrin-independent ameboid movement of the neutrophils.

AUTHORSHIP

C.C., T.G., H.R.L., and D.D.W. designed research; C.C., D.D., T.G., H.H., J.S., and S.M.C. performed research; C.C., D.D., H.R.L., and D.D.W. analyzed data; G.C.W. and M.C-W. bred and provided the rare Rap1b−/− animals; and C.C. and D.D.W. wrote the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL056949 and P01 HL066105 (both to D.D.W.); grant DFG GO1360/4-1 and IMF Münster (T.G.); NIH grants HL085100, AI076471, HL092020, and GM076084; and a research scholar grant from the American Cancer Society (H.R.L.). We thank Kulandayan Subramanian and Ian del Conde for helpful discussions and Lesley Cowan for assistance in preparing the manuscript. We thank Ann Graybiel, David Housman, and Jill Crittenden for providing the CalDAG-GEFI-deficient mice.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CalDAG-GEFI=calcium and diacylglycerol-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor I, CytoD=cytochalasin D, DIAS=Dynamic Image Analysis software, LTB4=leukotriene B4, Rap1=Ras-proximate-1, WT=wild-type

References

- Bokoch G M. Chemoattractant signaling and leukocyte activation. Blood. 1995;86:1649–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devreotes P N, Zigmond S H. Chemotaxis in eukaryotic cells: a focus on leukocytes and dictyostelium. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:649–686. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson T S, Ley K. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in leukocyte trafficking. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R7–R28. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00738.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D D, Frenette P S. The vessel wall and its interactions. Blood. 2008;111:5271–5281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-078204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorant D E, Patel K D, McIntyre T M, McEver R P, Prescott S M, Zimmerman G A. Coexpression of GMP-140 and PAF by endothelium stimulated by histamine or thrombin: a juxtacrine system for adhesion and activation of neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:223–234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers T W, Tool A T, van der Schoot C E, Ginsel L A, Onderwater J J, Roos D, Verhoeven A J. Membrane surface antigen expression on neutrophils: a reappraisal of the use of surface markers for neutrophil activation. Blood. 1991;78:1105–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R O. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky M I, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawista S E, de Boisfleury Chevance A. Random locomotion and chemotaxis of human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) in the presence of EDTA: PMN in close quarters require neither leukocyte integrins nor external divalent cations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11577–11582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malawista S E, de Boisfleury Chevance A, Boxer L A. Random locomotion and chemotaxis of human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes from a patient with leukocyte adhesion deficiency-1: normal displacement in close quarters via chimneying. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2000;46:183–189. doi: 10.1002/1097-0169(200007)46:3<183::AID-CM3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammermann T, Bader B L, Monkley S J, Worbs T, Wedlich-Soldner R, Hirsch K, Keller M, Forster R, Critchley D R, Fassler R, Sixt M. Rapid leukocyte migration by integrin-independent flowing and squeezing. Nature. 2008;453:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Springett G M, Toki S, Canales J J, Harlan P, Blumenstiel J P, Chen E J, Bany I A, Mochizuki N, Ashbacher A, Matsuda M, Housman D E, Graybiel A M. A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden J R, Bergmeier W, Zhang Y, Piffath C L, Liang Y, Wagner D D, Housman D E, Graybiel A M. CalDAG-GEFI integrates signaling for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2004;10:982–986. doi: 10.1038/nm1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier W, Goerge T, Wang H W, Crittenden J R, Baldwin A C, Cifuni S M, Housman D E, Graybiel A M, Wagner D D. Mice lacking the signaling molecule CalDAG-GEFI represent a model for leukocyte adhesion deficiency type III. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1699–1707. doi: 10.1172/JCI30575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour H, Cullere X, Alvarez A, Luscinskas F W, Mayadas T N. Essential role for Rap1 GTPase and its guanine exchange factor CalDAG-GEFI in LFA-1 but not VLA-4 integrin mediated human T-cell adhesion. Blood. 2007;110:3682–3690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-077628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinz F J, Seifert R, Schwaner I, Gausepohl H, Frank R, Schultz G. Generation of specific antibodies against the rap1A, rap1B and rap2 small GTP-binding proteins. Analysis of rap and ras proteins in membranes from mammalian cells. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H, Awasthi A, White G C, II, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Malarkannan S. Rap1b regulates B cell development, homing, and T cell-dependent humoral immunity. J Immunol. 2008;181:3373–3383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yan J, De P, Chang H C, Yamauchi A, Christopherson K W, II, Paranavitana N C, Peng X, Kim C, Munugalavadla V, Kapur R, Chen H, Shou W, Stone J C, Kaplan M H, Dinauer M C, Durden D L, Quilliam L A. Rap1a null mice have altered myeloid cell functions suggesting distinct roles for the closely related Rap1a and 1b proteins. J Immunol. 2007;179:8322–8331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Smyth S S, Schoenwaelder S M, Fischer T H, White G C., II Rap1b is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:680–687. doi: 10.1172/JCI22973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Lu H, Norman K, van Nood N, Munoz F, Grabbe S, McArthur M, Lorenzo I, Kaplan S, Ley K, Smith C W, Montgomery C A, Rich S, Beaudet A L. Spontaneous skin ulceration and defective T cell function in CD18 null mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:119–131. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanegasaki S, Nomura Y, Nitta N, Akiyama S, Tamatani T, Goshoh Y, Yoshida T, Sato T, Kikuchi Y. A novel optical assay system for the quantitative measurement of chemotaxis. J Immunol Methods. 2003;282:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori H, Subramanian K K, Sakai J, Jia Y, Li Y, Porter T F, Loison F, Sarraj B, Kasorn A, Jo H, Blanchard C, Zirkle D, McDonald D, Pai S Y, Serhan C N, Luo H R. Small-molecule screen identifies reactive oxygen species as key regulators of neutrophil chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3546–3551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914351107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Entschladen F, Conrad C, Niggemann B, Zanker K S. CD4+ T lymphocytes migrating in three-dimensional collagen lattices lack focal adhesions and utilize β1 integrin-independent strategies for polarization, interaction with collagen fibers and locomotion. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2331–2343. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2331::AID-IMMU2331>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glogauer M, Marchal C C, Zhu F, Worku A, Clausen B E, Foerster I, Marks P, Downey G P, Dinauer M, Kwiatkowski D J. Rac1 deletion in mouse neutrophils has selective effects on neutrophil functions. J Immunol. 2003;170:5652–5657. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Pertz O, Hahn K, Bourne H. Neutrophil polarization: spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity support a self-organizing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3639–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600092103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S. Cdc42—the centre of polarity. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1291–1300. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammermann T, Renkawitz J, Wu X, Hirsch K, Brakebusch C, Sixt M. Cdc42-dependent leading edge coordination is essential for interstitial dendritic cell migration. Blood. 2009;113:5703–5710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamborn J C, Puschel A W. The sequential activity of the GTPases Rap1B and Cdc42 determines neuronal polarity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:923–929. doi: 10.1038/nn1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Kawasaki H, Tashiro N, Housman D E, Graybiel A M. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors CalDAG-GEFI and CalDAG-GEFII are colocalized in striatal projection neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2001;437:398–407. doi: 10.1002/cne.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T H, Gatling M N, McCormick F, Duffy C M, White G C., II Incorporation of Rap 1b into the platelet cytoskeleton is dependent on thrombin activation and extracellular calcium. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17257–17261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuni S M, Wagner D D, Bergmeier W. CalDAG-GEFI and protein kinase C represent alternative pathways leading to activation of integrin αIIbβ3 in platelets. Blood. 2008;112:1696–1703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-139733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E M, Rae S A, Smith M J. Leukotriene B4, a mediator of inflammation present in synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983;42:677–679. doi: 10.1136/ard.42.6.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks S W, Bayley D L, Hill S L, Stockley R A. Bronchial inflammation in acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: the role of leukotriene B4. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:274–280. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15b09.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins R J, Piel M, Faure-Andre G, Lennon-Dumenil A M, Joanny J F, Prost J, Voituriez R. Pushing off the walls: a mechanism of cell motility in confinement. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:058103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.058103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkawitz J, Schumann K, Weber M, Lammermann T, Pflicke H, Piel M, Polleux J, Spatz J P, Sixt M. Adaptive force transmission in amoeboid cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1438–1443. doi: 10.1038/ncb1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]