Abstract

Current evidence indicates that individuals and families who engage in self-management (SM) behaviors improve their health outcomes. While the results of these studies are promising, there is little agreement as to the critical components of SM or directions for future study. This paper offers an organized perspective of similar and divergent ideas related to SM. Unique contributions of prior work are highlighted and findings from studies are summarized. A new descriptive mid-range theory, Individual and Family Self-management Theory, is presented; assumptions identified, concepts defined, and proposed relationships outlined. This theory adds to the literature on self-management by focusing on individual, dyads within the family, or the family unit as a whole; explicating process components of self-management; and proposing use of proximal and distal outcomes.

The need to manage chronic conditions and to actively engage in a lifestyle that fosters health is increasingly recognized as the responsibility of the individual and their family. Health problems have shifted from acute to chronic and personal behaviors are linked to over half of chronic health problems.1,2 Health care delivery has shifted to non-hospital venues with hospitalizations often eliminated or shortened. Criteria for hospital discharge are related to outcomes of conditions or procedures rather than the ability of patients or families to manage care.1 It is estimated that half of all Americans are managing a serious chronic health condition at home. Over 12% of children have special health care needs and 23% of these children are significantly impacted by their condition.3 In adults, 7% of persons between the ages of 45 and 54 and 37% of person over the age of 75 are managing three chronic conditions.1 While the values of health promotion are increasingly realized for individuals and families, few health-promoting strategies are routinely incorporated into the delivery of health care in many settings. Individuals and families are expected to sort through the myriad of contradictory health information of varying quality and engage in behaviors promoting their health. Personal efforts to engage in healthy behaviors are often derailed by social factors incongruent with health,1, 4 such as neighborhoods unsafe for exercise, peer-group norms related to food choices and alcohol, and expectations inherent is some family traditions.

As nurses and other health care professionals our expectations for individuals and families to assume responsibility for managing their health care have outpaced our understanding of how to assist them to acquire the knowledge, skills, and social facilitation for health management. Studies related to the efficacy of self-management (SM) behaviors offer significant promise to improving health outcomes.5–11 For individuals and families the management of chronic health conditions leads to the improvement of their health outcomes, increased quality of life, realignment of health care expenditures including a decreasing demand for health services, and SM also contributes to the overall health of society.12 Likewise, managing risk factors can improve health outcomes by preventing, delaying, or attenuating health conditions. While SM appears to offer significant promise, widespread agreement of what individual and family self-management actually is and how it can be developed is just beginning to be understood.

The purposes of this paper are to identify gaps in the science of SM and present a descriptive mid-range SM theory. Specific aims include (a) defining SM and identifying issues related to the conceptual clarity of the concept, (b) providing an understanding of the divergence in current conceptual and theoretical thinking and research; (c) presenting The Individual and Family Self-management Theory (IFSMT), including a description of assumptions, concepts, and the relationships among concepts; (d) and identifying opportunities for future study of SM. Select conceptual and methodological issues related to the study of individual and family SM are identified.

Definition and Conceptual Clarity

Recognizing what is known about SM and identifying gaps in theory and research enhances a shared understanding of the phenomenon of SM. Comparing and contrasting similar but different phenomenon leads to a clearer conceptualization.13 Individuals or families assume responsibility for the SM of chronic conditions or engagement in healthy behaviors by purposefully performing of a cluster of learned behaviors.8,9,12,14–18 Living with a condition or engaging in healthy behavior is complex and requires integration of SM behaviors into the lifestyles of individuals and families.16,19 SM is a multidimensional, complex phenomenon that can be conceptualized as affecting individuals, dyads, or families across all developmental stages. Traditionally SM focused on individuals or families. SM, as defined here, uniquely combines these parallel theories; integrating individual and family self-management. From the perspective of systems theory, a change in one component of a system, i.e., family member leads to changes in the system (family), and all of its members. An individual’s capacity and needs affects the success or failure of the individual or the family to SM. Combining individual and family perspectives enhances our understanding the dynamic shifts in balance. Family members assume different roles over time; for example there are times when adults assume a major role in the management with chronic conditions in children. But roles change when children transition into adolescence or when older adults experience diminishing capacity. Continual changes in family balance occur day-to-day over time necessitating SM and SM support to be dynamic and fluid.

An understanding of the term SM differs across authors and programs of research hampering a unified approach. Blurring of the concept results in delaying knowledge development, impedes the development of sensitive measures and interventions, and slows the translation of research to practice. Historically, SM has been used to refer to three different phenomena; namely a process, a program, or an outcome. The process of SM refers to the use of self-regulation skills to manage chronic conditions or risk factors.6,15,20–24 These processes generally include activities such as goal setting, self monitoring and reflective thinking, decision making, planning for and engaging in specific behaviors, self evaluation and management of physical, emotional and cognitive responses associated with health behavior change. SM programs or interventions are designed by health care professionals with the intent of preparing persons to assume the responsibility for managing their chronic illnesses or engaging in health promotion activities.6,8,9,17,25–34 SM has also been used to describe outcomes achieved by engaging in the SM process, such as stabilization of Hemoglobin A1C levels in persons with diabetes or smoking cessation.1,7,35–38

Self-care and patient education are concepts related, but distinct from, SM.39 SM and self-care are similar in that a person engages in specific behaviors to achieve an outcome. However the activities or processes and outcomes differ between self-care and SM. Self-care is a term which has been used to refer to performance of activities of daily living such as bathing or toileting;40 engagement in health behaviors without collaboration or direction from a legitimate health care source;41 or as a construct of a nursing grand theory, The Self Care Theory.42 When individuals and families self-manage they control and are responsible for management of chronic conditions or healthy behaviors by purposefully engaging in performance of learned behaviors.8,9,12,14–18 Unlike focusing on performance of daily activities or engaging in behaviors independent of the traditional health care system, SM involves knowledge and beliefs, self-regulation skills and abilities, and social facilitation to manage chronic conditions or engage in healthy behaviors.

The term patient education is often used interchangeably with SM interventions or programs. Failure to distinguish patient education from SM programs results in failure to understand differences in the impact of the two different types of interventions on specific outcomes. Patient education as a method of providing information has been associated with outcomes such as increased knowledge, increased satisfaction, or change in readiness to engage in a health behavior; whereas SM programs and interventions facilite development of SM skills and activities designed to enhance health behavior change, decreased health care costs, and increased quality of life or well being.6,19,43,44

Substantive differences in definitions and key concepts blur the realization that SM involves the use of specific processes, can be affected by specific programs and interventions, and results in specific types of outcomes. Distinguishing patient education and self-care from SM enhances the clarity of the concepts and promote knowledge development. Precise definitions and conceptual clarity enhance knowledge development.

Review of SM Literature: Conceptual and Theoretical Perspectives

The literature on the underpinning of SM contains a number of similar and divergent perspectives. Definitions, conceptual perspectives, and descriptions of theoretically based interventions are widely varied. While there is evidence some scholars and researchers have been influenced by the work of others and their work builds upon each other, it is equally apparent other researchers and scholars hold different and unique perspectives. This review of SM literature includes divergent sources of conceptual perspectives. These divergent perspectives can be seen across three types of literature; specifically (a) articles focusing on theoretical constructs including risk and protective factors and complementary outcomes, processes of self-regulation, and tasks common across chronic conditions, (b) articles that included descriptions of theoretically based SM interventions and programs, and (c) articles focusing on the efficacy of theoretically based SM reviews of research. Divergence was explored to facilitate identification of new and blended perspectives.

Theoretical constructs

Risk and protective factors and complementary outcomes

In “Self and Family Management Framework” Grey, Knafl, and McCorkle16 purport that SM occurs within the context of families, communities and the environment and is influenced by risk and protective factors. Based on a review of literature and combined findings of their quantitative and qualitative funded, productive programs of nursing research these authors identified and categorized risk and protective factors and their complementary outcomes. These contextual risk and protective factors include health status, individual factors, family factors, and environmental factors. Each risk and protective factor had empirically based subcategories; such as the category of health status having subcategories of severity of the condition, characteristics of the treatment regimen, disease trajectory, and genetics. Outcome categories for health status complement or match risk and inclusion factors and include perceptions of control, morbidity, and mortality. Their work focused on understanding SM in children and their families.

This work makes a major contributions by furthering the understanding of self and family management, the delineation of risk and protective factors associated with family SM, and resultant health outcomes. Gaps in the work includes omitting a description of the actual processes families use to engage in SM behaviors. In addition, short and long-term outcomes are combined, obscuring the potential to discover the impact of short-term outcomes on long-term outcomes. This framework refers to persons and families but focuses on impact of the child on families and the families need to manage the care required for children with chronic conditions. Missing is the impact of the child on the needs of the adult person and other family members to manage their own health and the potential impact children can have on the health and well-being of the family and other members.

The process of self-regulation

The writings of Baumeister,45 Boekaerts,20 Carver,21,22 Creer,15, Holroyd,23 and Tobin46 focus on self-regulation, a process integral to engaging in SM behaviors. This work is based on the Social Learning Theory/Social Cognitive Theory47–49 which identifies reciprocal impact of an individual’s social and physical environment, thoughts or cognitive processes, and actual behaviors upon each other: A concept called reciprocal determinism. These authors purport that engagement in self-regulation behaviors enhances self-efficacy and leading to engagement in SM behaviors (such as lower intake of simple carbohydrates). Self-regulation includes goal-setting, self-monitoring and reflective thinking, decision-making, planning and action, self-evaluation, and management of physical, emotional and cognitive responses associated with health behavior change. Considerable empirical work supports the essential components and outcomes achieved when these behaviors are utilized singularly and in combination. For these authors, SM is the process of engaging in specific behaviors enhancing a person’s ability to manage a chronic illness or risk behaviors (health promotion).

Tasks common across chronic conditions

Clark, Becker, Janz, Lorig, Rakowski, and Anderson41 conducted a review of literature published in the 70s and 80s to determine whether or not SM tasks were common across chronic diseases in adults and older adults. They evaluated five chronic diseases; heart disease (11 articles), asthma (11), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (6), arthritis (10), and diabetes (5). Self-management was operationalized either as tasks performed “handling clinical aspects of the disease away from the hospital or physicians office” (p.4) or as psychosocial coping. They concluded there were 12 tasks common to SM across chronic diseases; specifically, symptom management, taking medications, recognizing acute episodes, nutrition, exercise, smoking, stress reduction, interaction with health providers, need for information, adapting to work, managing relations, and managing emotions. While there were only five studies that included an adequate number of older adults in the review, there was no evidence of differences in tasks between adults and older adults. Knowledge and social support were mentioned as critical to the success of a person’s ability to self manage. They found the Social Cognitive Theory47–49 and the principles of self-regulation helpful in explaining this early work. This article by Clark and colleagues41 documents aspects of the historical research related to SM and reflects the insights and integration of well-recognized and respected researchers. Documented associations among concepts paved the way for testing causative relationships among concepts and outcomes.

Interventions and Programs

Individual interventions and programs containing SM

Lorig and colleagues8–10,29,45,50–53 conducted numerous empirical studies testing the impact of SM programs on outcomes. In a 2003 article, Lorig identified that SM is based on the work of a number of theorists;19 specifically Bandura’s work on self-efficacy, Creer’s original work on SM, D’Zurilla on problem solving, Corbin and Straus on chronic illness, and Patterson shifting perspectives from chronic illness to wellness. In a more recent communication (Personal communication, September 17, 2008) she noted Banduras work on self-efficacy as the dominant theoretical perspective influencing her work and shared content from a slide presentation explicating this perspective. Accordingly SM “is the tasks individual must undertake to live with one or more chronic condition. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with the medical management, role management and emotional management of this condition.” (http://patienteducation.stanford.edu)

While individuals engage SM, health care professionals provide SM support consisting of education and supportive interventions. She identified six management skills; specifically problem solving, decision-making, resource utilization, formation of patient-provider relationship, development of an action plan, and self-tailoring.

Lorig and colleagues have made consistent and major contributions to knowledge related to SM programs. Studies conducted across a number of different conditions have resulted in an understanding that there are SM requirements common across chronic conditions; such as, management of medication, roles, symptoms, and relationships with persons in the health care system. Core content has been identified and tested across conditions, cultures, and languages. Successful delivery methods span small groups and electronic delivery methods and the importance of lay advisors has been identified and validated across studies. These programs are recognized and used nationally and internationally by individual providers, health care systems, and health organizations (http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/).

Since the inception of these programs family members or significant others have been included in the program as support persons – but the focus has not been “family-management”. The concept of self-efficacy plays an increasingly important role across Lorig’s program of research. Engagement in SM programs results in positive outcomes related to personal health status, system use, and cost. While all SM programs are evidence based, Lorig’s approach to SM programs begins with and focuses on the issues and concerns relevant to the individual.

Lorig and colleagues have focused primarily on chronic conditions rather than health promotion or risk and protective factors. Sample sizes are generally large and many programs are tested in real world clinical settings rather than settings established for the purposes of the study; hence the external validity or generalizability of these studies tends to be high. Their SM programs are based on the perceived needs and experiences of persons actually living with a condition as obtained via focus group interviews. Outcome measures typically include single items and clinically relevant assessment tools in addition to standardized instruments with demonstrated psychometrics. Crossover designs are used frequently possibly because these researchers have repeatedly demonstrated positive outcomes. Crossover designs circumvent the ethical issues associated with not providing a treatment with strong evidence of effectiveness to one group of persons but the design limits comparison of treatment group with a control group over time.

Significant contributions to SM by other groups must be noted. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services contracted with the Rand Corporation to prepare a report on behalf of the Southern California Evidence Based Practice Center12. Rand proposed six elements central to SM programs; specifically, tailoring, group delivery methods, feedback, focus on medical care, and a focus on psychological responses. They categorized studies based on medical conditions (diabetes, n=12; hypertension, n=14; osteoarthritis, n=7; and post myocardial infarction care n=9) and concluded there was inadequate evidence to support any of these six factors as essential to the success of SM programs. Alternatively, they found no evidence refuting the importance of any of these factors. They did find evidence that chronic disease SM programs were effective in reducing health care costs. Outcomes were not evaluated in terms of the six proposed elements of SM alone or in combination–thus it is not possible to determine whether outcomes were associated with the elements of the programs. Physician reviewers developed the list of the six program components rather than drawing the list from a theoretical model or using criteria from prior research.

Component of a comprehensive program

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) developed by Wagner and colleagues identifies SM support as one of its six essential components.6,17,18,26–28,34,35,54 The CCM is a complex, multi-dimensional structured process designed to facilitate the health care management of persons with chronic illnesses. CCM involves the entire community (resources as well as public and private policies), the health care system including payment structures, and the provider organization ranging from small clinics to integrated delivery systems. The six essential components of this model include community resources and policies, health care organizations, SM support, delivery-system design, decision support for health care providers, and an electronic clinical information system. In this model SM support focuses on assisting persons to develop the skills necessary to increase their confidence, provision of necessary equipment and tools (e.g., glucometers, exercise prescriptions, or referrals), and regular contact with members of the health care team to address problems and acknowledge accomplishments.

Bodenheimer6 conducted a review of the effectiveness of the CCM and found that no single element emerges as essential to the model. However he found that patient outcomes improved in 19 of the 20 studies that included SM support–providing evidence of the impact observed when SM support is a component of chronic care. Details of SM support are available in manuals prepared by the CCM team (http://www.improvingchroniccare.org).

Parry, Kramer, and Coleman32,55–58 developed and are testing a program to facilitate transitioning across care delivery systems while maintaining or improving patient outcomes. Their Care Transition program is an interdisciplinary program that occurs over a 30-day period of time. The intervention focuses on medication SM, a patient-centered record, and follow-up with health care providers, and knowledge/self management of conditions. All participants have a specifically designed Personal Health Record. Nurses serve as transition coaches, teaching persons about their conditions and enhancing their skills to manage their illness and communicate with members of the health care team. Details of the program are available in manuals prepared and used in during formal testing. Efficacy of the program is being tested currently (http://www.caretransitions.org/).

Efficacy of Interventions and Programs

A review of 145 articles was conducted by Barlow and colleagues14 to determine the efficacy of SM interventions and programs. This review was limited to chronic conditions (66 articles related to asthma, 18 to diabetes, and 17 to arthritis). While the majorities of studies were conducted in the United States (n=82), studies were also from the United Kingdom (n=13), Australia (n=10), and in other countries (n=40). Most of the studies focused on adults, and several studies included both children and adults with asthma. SM programs were delivered across all venues via numerous delivery methods. In the majority of studies more than one delivery method was used. SM interventions included content related to condition-specific information, drug management, symptom management, self-regulation enhancement, and social support. Outcomes measures included physical, psychological, health status, knowledge, medication usage, self-efficacy, and use of SM behaviors. Compared to standard care recipients, participants benefited in terms of knowledge, performance of SM behaviors, self-efficacy, and health status. Venue and delivery method did not alter the positive impact of delivering SM interventions.

Summary: Gaps and Opportunities

The concept of SM has been developed, tested, and used over the past four decades. Interventions and programs have been designed and tested. There is a growing body of empirical evidence that SM interventions and programs improve the outcomes of persons with chronic illness. There is increasing evidence there is a common grouping of SM tasks across multiple chronic conditions–providing evidence of the need for condition specific as well as non-condition specific interventions to enhance SM. SM interventions and programs are effective for adults and children and their families. There is very promising evidence that outcomes from SM interventions and programs are more effective than usual care or traditional patient education. Inclusion of SM interventions into well-respected and innovative chronic care programs provides testimony to their effectiveness in clinical setting.

However, gaps exist in the understanding individual and family SM, the process of SM, and identification and measurement of outcomes sensitive to short term behavior change and the impact of health behavior on long range outcomes such as health status, cost, and quality of life. There is a considerable gap in our understanding of the similarities and differences of SM across developmental stages (young to older adult) and reciprocal relationships other’s play in SM. Individual and family SM needs to be studied in children as well as in adults. While it is evident that parents and other adults are actively involved in SM tasks of children; significant others, as well as children, impact SM of adults.

The processes individuals and families use to SM need to be explicated. Is the process similar for individuals and families? As young children develop, SM is most likely a transitional process. Is this transition process similar in any respect to declining SM abilities in older adults? Isn’t it possible that young children and older adults have the capacity to contribute to adult SM?

Determining impact of health behavior change on health status is especially challenging for numerous condition and measurement related issues. Yet there is a real need to determine the efficacy of interventions on behaviors long before any change to health status could be observed. Hence there are opportunities to conceptualize SM outcomes as both proximal and short term and distal or long term.

Individual and Family Self-management Theory (IFSMT): A New Mid-Range Descriptive Theory

Gaps in SM knowledge and opportunities for continued knowledge development benefit from new theories. A new theory, IFSMT, is presented here as an alternative perspective. This new theory is being used to influence study designs, intervention and measurement development, and is being tested across multiple conditions and populations. Rodgers, a recognized and well respect nurse theorist and University of Milwaukee Wisconsin Self-management Center Scientist, proposed this new mid-range theory be considered a descriptive theory. Descriptive theories are based on deductive and inductive processes and

…reveal the substance of a situation yet without structured linkages showing the specific nature of relationships among components. Over time parts of theories can be explored further to clarify vague aspects or to identify the scope of contexts in which it is reasonable to apply the theory. Theories, as a result, may move progressively toward a more formal end of the continuum because relational statements are refined to the point that they take the form of propositions. In the process of theory development, it is important not to expect all theory to be moved to a formal level. The value of descriptive, substantive theory easily can be overlooked in such a scheme”59(p. 192)

SM is a multidimensional, complex phenomenon that can be conceptualized as affecting individuals, dyads, or families across all developmental stages. SM includes condition specific risk and protective factors, component of the physical and social environment, and unique characteristics of individuals and family members. It includes the processes of SM; specifically, facilitation of knowledge and beliefs, enhancement of self-regulation skills and abilities, and social facilitation. SM affects a number of outcomes, both short and long term. SM behaviors are used to manage chronic conditions as well as to engage in health promotion behaviors. New theory is needed to provide the conceptual basis for development and testing of SM.

While individual centered practice contributes to the understanding of SM expanding from the individual to the individual and family SM has the potential to add further insight to SM behaviors. According to family systems theory, a change in one family member leads to changes in the system and all members of it. Building on the perspective of Feetham and Thomson60 outcomes improve when individuals and families are seen through both the “individual lens” and the “family lens”. Using both lenses simultaneously allows the health care provider a comprehensive perspective; maintaining a focus on the individual while taking into account the family, friendship network, and community relationships. This multidimensional vision can reflect a changing balance in the individual and family systems. In the past analysis of pairs, small groups, and intergeneration of families was limited by statistical analysis. The state of the science for analysis now offers promising solutions to these problems.61,62

Applying for and receiving a P20 award to establish the Self-management Science Center (Marek, 1P20NR0010674-01) provided an opportunity to combine Ryan’s Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC)63,64 in review and to expand prior work on SM with concepts from Sawin and colleagues Ecological Model of Secondary Conditions and Adaptation.65,66 The ITHBC originally emerged from a review of interventions used to facilitate health behavior change. It was observed that successful change in health behavior was associated with interventions that addressed condition specific knowledge and health beliefs, fostered an increase in self-regulation skills and abilities, and enhanced social facilitation. The ITHBC was used in practice settings with individual persons, provided the structure for clinical programs of care, and provided the theoretical foundation for development of interventions being prepared for testing in efficacy studies. Select instruments were identified or developed and early results of tests of this theory are very promising67.

Sawin and her colleagues focused on the individual in the context of family, specifically identifying and measuring risk and protective factors leading to the enhancement of SM. Ryan and Sawin saw their work as complementary and when combined led to unique and promising opportunities to test and understand different dimension of self-management. Together with feedback and suggestions from Center directors and faculty, these models provided the foundation for a newly expanded theory, IFSMT. This theory provides the theoretical foundation for the five competitive studies that are being conducted as part of the P20 award. This new theory will provide a foundational to the work of UWM doctoral and masters students related to SM. The continued work of Center scientists will contribute to the testing of this theory with current and proposed research.

Individual and Family SM: Conceptual Definition

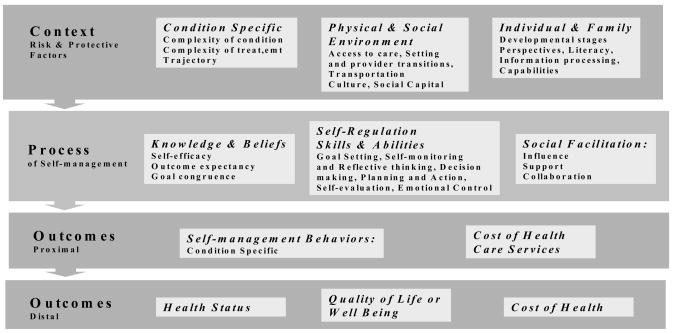

Individual and family SM includes the purposeful incorporation of health related behaviors into an individual or family’s daily functioning. The family unit is not limited to biological families. Individual and family SM prevents or attenuates illness or facilitates the management of complex health regimens in ways that reflect individual and family values and beliefs in personally meaningful ways. The individual or family assumes responsibility for individual and family SM and may occur in collaboration with health care professionals (Model, Figure 1; Conceptual Definitions, Table 1; and Assumptions, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Model of the Individual and Family Self-management Theory

Table 1.

Individual and Family SM Theory: Definition of Major Concepts.

| Context: Risk and Protective Factors: Condition specific factors that challenge or protect individuals and families engagement in SM. | |

| Condition Specific | Physiological, structural, or functional characteristics of the condition, its treatment, or prevention of the condition that impact the amount, type, and critical nature of behaviors needed to manage the condition during times of stability or transition (e.g., complexity of condition or treatment, trajectory, physiological stability, or physiological transitions). |

| Physical & Social Environment | Physical or social factors including factors such as access to health care, transition in health care provider or setting, transportation, neighborhoods, schools, work, culture, and social capital that enhance or present barriers to individual and family SM. |

| Individual & family factors | Characteristics of the individual and family that enhance or diminish SM; for example individual cognitive status, perspectives, information processing, developmental stages, individual and family capabilities and cohesion, literacy, resourcefulness. |

| Processes and their enhancement: based on the dynamic interaction among the following: a) condition-specific knowledge and beliefs, b) acquisition and use of self-regulation skills and abilities, and c) social facilitation and negotiation. | |

| Knowledge & Beliefs | Factual information and perceptions about a health condition or health behavior. Including self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and goal congruence Self-efficacy is a behavior specific concept and refers to the degree of confidence one has in his/her ability to successfully engage in a behavior under normal and stressful situations. Outcome expectancy is a belief that engagement in a particular behavior will result in desired outcomes. Goal congruence is a person’s ability to resolve the confusion and anxiety occurring from apparent contradictory and competing demands associated with health goals |

| Self–regulation | Self-regulation is an iterative process people engage in to achieve a change in health behaviors. Self-regulation includes a number of skills and abilities including:

|

| Social facilitation | Social facilitation occurs within relationships and enhances an individual’s capacity to change: includes social influence, support, and negotiated collaboration. Social influence is a message or dialogue in which respected persons in positions of perceived authority with expert knowledge advises and encourages individuals and families to engage in specific health behaviors. These respected persons may be health care providers, family, friends, neighbors, work colleagues, and members of community groups or printed or electronic medium such as magazines, television, or the internet. Social support consists of emotional, instrumental, or informational support provided to a person or family with the explicit goal of assisting or facilitating their engagement in health behaviors. Negotiated Collaboration occurs when “your, mine, and our” perspectives are respected and influential. Professional expertise and standards, individual meaning, and mutual family roles and responsibilities influence goals and recommended treatments. |

| Outcomes: includes proximal or short term outcomes that lead to attainment of distal outcomes | |

| Proximal Outcomes | Individual and family self-management behaviors: including engagement in activities/treatment regimens, symptom management, or use of recommended pharmacological therapies. Engagement in health behaviors may or may not impact cost of health care services. |

| Distal Outcomes |

|

Table 2.

Assumptions of the Individual and Family Self-management Theory

|

The definition of SM used in the IFSMT is consistent with situation specific SM definitions, providing evidence of the utility of this mid-range theory to specific clinical situations.68 For example, Sawin and colleagues adapted Shilling and colleagues definition of SM for youths with diabetes.37 for their work with adolescents with spina bifida (adaptation in italics).66

…an ongoing process of shared decision-making and responsibility among youth with disabilities and their parents to achieve control of their condition, health, and well being through a wide range of activities and skills. The goal of this increasing responsibility is to develop skills needed for transition to adulthood and independent living.

Individual and Family Self-management Theory

The Individual and Family Self-management Theory proposes that SM is a complex dynamic phenomenon consisting of three dimensions: context, process, and outcomes.69, 70 Factors in the contextual dimension influence individual and family engagement in the process of SM as well as directly impact outcomes. Enhancing the individuals and families SM processes results in more positive outcomes. The third dimension of the theory relates specifically to outcomes. Outcomes are proximal or distal. While the outcomes of concern are those related to individuals and families, improvement of individual and family outcomes translate to improved outcomes for health care practitioners and systems

Context dimension: risk and protective factors

Contextual factors, drawn primarily from Sawin and colleagues’ work and the literature, are risk or protective factors and include condition specific factors, physical and social environments, and individual and family characteristics.37,65,66 Condition specific factors are those physiological, structural, or functional characteristics of the condition, its treatment, or prevention of the condition that impact the amount, type, and nature of behaviors needed to SM. Examples of condition specific factors are complexity of condition or treatment, trajectory, physiological stability, or physiological transitions.71–76 Environmental factors are physical or social and include factors such as access to health care, transition from one health care provider or setting to another, transportation, neighborhood, work, school, culture,77–81 or social capital.38,82–86 Individual/family factors are those characteristics of the individual and family directly.63, 87 in review

Process dimension

Concepts of the process dimension are consistent with the Institute of Medicine report on Health and Behavior4 and based in health behavior theories, research, and practice. The model was influenced by theories of health behavior change,4,41,47–49,88–102 self-regulation theories,15,20–24,45 social support theory,4,47,49,88–90,103–107 and research related to SM of chronic illnesses.8,11,14,15,17,19,23,26,28,29,31,33,36,41,108–110 According to this descriptive theory, persons will be more likely to engage in the recommended health behaviors if they have information about and embrace health beliefs consistent with behavior, if they develop self-regulation abilities to change their health behaviors, and if they experience social facilitation that positively influences and supports them to engage in preventative health behaviors.14,50,111,112 Knowledge and beliefs impact behavior specific self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and goal congruence. Self regulation is the process used to change health behavior and includes activities such as goal setting, self monitoring and reflective thinking, decision making, planning for and engaging in specific behaviors, self evaluation and management of physical, emotional and cognitive responses associated with health behavior change. Social facilitation includes the concepts of social influence, social support, and negotiated collaboration between individuals and families and health care professionals.

Outcome dimension

Outcomes in this theory are both proximal and distal. The proximal outcome is actual engagement in SM behaviors specific to a condition, risk, or transition, in addition to managing symptoms, and pharmacological therapies. Cost associated with health care use is a proximal outcome. Distal outcomes are related, in part, to successful achievement of proximal outcomes. These outcomes fall into three primary categories: health status; quality of life or perceived well being and cost of health--both direct and indirect.

Interactions Among Constructs

The context, risk and protective factors affect each other. For example it is well documented that disability and the number of chronic diseases are linked with socioeconomic status, access to care, quality of care, and work and educational opportunities.1,4,12,65,77–83,105,113,114 Likewise years of education, personal characteristics, and literacy are linked to individual’s ability to manage complex regimens.39,41,65,72–76,113,115–120 The young and old are increasingly vulnerable, persons with poor health literacy experience poorer health outcomes, individuals cognitively challenged, even with the support of family, cannot manage complex health regimes as well as individuals not cognitively challenged. Together factors in the context dimension affect an individual’s and family’s ability to engage in the process dimension and have direct impact on outcomes.

Constructs in the process dimension are linked to constructs in the context dimension, are internally related, and affect the outcome dimension. While it is well recognized that knowledge, in and of itself, does not lead to behavior change, enhancement of knowledge and specific health beliefs are linked to engagement in self-regulation behaviors.2,19,43,44,51,110,118,121–123 Social facilitation is inter-related with knowledge and beliefs and self-regulation. Knowledgeable engagement in supported self-regulation behaviors leads to engagement in SM behavior, or proximal outcomes.8–10,12,14,27,30,33,51,52,124

Constructs of the outcome dimensions are affected by both context and process dimensions. Outcomes are proximal and distal; with achievement of proximal outcomes, causing, at least in part, distal outcomes. For example, SM of diabetes resulting in controlled Hemoglobin A1C results in improved morbidity and mortality. SM of heart failure resulting in accurate use of pharmacological agents and weight management results in improved quality of life as well as improved health status. Engagement in disease specific behaviors is associated with decreased cost.1,25,34,36

Continued use and testing of the model should result in increased parsimony of the theory, revealing concepts essential to SM. Quantitative and qualitative approaches to using and testing the theory will improve clarity and provide an increased understanding of which concepts mediate and moderate SM. Testing is needed to determine whether or not select concepts are supported across the phenomenon of SM in general and whether or not concepts are applicable for sub-populations or conditions; hence the ability to use this mid-range theory as a situation-specific theory.68

Interventions

Individual and family-centered interventions impact SM by addressing either the context or the SM process. Interventions aimed at the context can reduce risk or foster conditions that support SM. Interventions aimed at the SM process can enhance knowledge and beliefs, increase an individual’s use of self-regulation behaviors and foster social facilitation.

Potential Impact of IFSMT

This new, descriptive theory strengthens the prior work on self-management. Risk and protective factors have been expanded. The process components of SM have been delineated, a noteworthy addition to prior conceptual models. Social forces have been expanded and developed. Outcomes have been conceptualized as proximal and distal and formalize the addition of quality of life, well being, and cost to health status outcomes. This theory is novel in that it provides the foundation for expanding our understanding of SM from the adult or the child and his or her family to individual as a member of a social unit. This theory expands the focus from health behavior change for chronic illness to the potential to include health behavior change required for health promotion. The IFSMT provides a foundation for development of interventions and measures and the proposed relationships will facilitate testing of mediation and moderation. This theory recognizes and uses the major contributions of decades of research and scholarship that has emerged from the collaboration of nurses and other health care professionals.

Summary

The IFSMT is a new descriptive theory that offers a number of advantages. This theory combines and expands prior work related to individual and family SM, focusing on the individual, dyads within the family, or the family unit. This theory attends to the contextual factors known to affect SM, the process of SM, and proposes relationships among contextual and process dimensions. The expanded theory is robust offering numerous new opportunities for expanding knowledge related to SM. Work of researchers, both internal and external to the UWM SMS Center, will over time, help identify those theoretical concepts essential to engagement in SM behaviors. Research, planned and in progress, is exploring contextual factors in individuals and family processes components from qualitative and quantitative perspectives.

This paper offers scholars an organized perspective on the similar and divergent ideas reflected in past and current publications on SM. This article contributes to the literature on SM in several ways. A substantive body of SM literature has been reviewed and organized by issues and themes. Critical and widely divergent articles have been selected for review. The contributions to SM have been identified for the select articles, programs of research, and clinical programs. The IFSMT is introduced, concepts defined, and proposed relationships outlined. This expanded theory combines family and individuals in a way that facilitates study of individuals, family dyads, or the family unit. Constructs of context, process, and outcomes are uniquely combined within this theory. Concepts related to context have been expanded. Process components have been clearly explicated. Outcomes are viewed as proximal and distal. Future articles will provide exemplars of how the IFSMT is foundational to proposal and intervention development. Discussion of issues, like contributions of quantitative and qualitative research to theory development and testing, are forthcoming.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Center for Enhancement of Self-management in Individuals and Families (Marek, 1P20NR0010674-01)

Tailored Computerized Intervention for Behavior Change (Ryan, 1R15NR009021-01A2)

Patient Centered Informational Interventions (Brennen, Ryan Post-Doctoral Fellowship, T32NR07102)

Secondary Conditions and Adaptation in Spina Bifida. (Brie, Sawin, Monasterio & Webb) Association of University Centers on Disability and CDC Special Collaborative Grants Project

Adaptation in Spina Bifida: Longitudinal Study of Adolescents and Young Adults. University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Research Growth Incentives Award (Sawin)

Suzanne Feetham for her critique, comments and suggestions during the preparation of the manuscript. Faculty involved in the Self-management Science Center at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee College of Nursing for their insights and questions related to the IFSMT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Polly Ryan, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Center Scientist, Self-management Science Center.

Kathleen J. Sawin, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and College of Nursing, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Center Scientist, Self-management Science Center.

References

- 1.Center For Disease Control: Chronic Disease Program. [Accessed March 28, 2008];Chronic Disease Overview. http://www.cdc.gov/print.do?url=http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/overview.htm.

- 2.Speaking of Health: Assessing Health Communitions Strategies for Diverse Populations. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2002. Institute of Medicine: Committee on Communication for Behavior Change in the 21st Century. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dyck PC, Kogan MD, McPherson MG, Weissman GR, Newacheck PW. Prevalence and characteristics of children with special health care needs. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:884–890. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences: Committee on Health and Behavior: Research, Practice and Policy Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed March 27, 2008];Preventing disability in the elderly with chronic disease. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/elderdis.htm.

- 6.Bodenheimer T. Interventions to improve chronic illness care: Evaluating their effectiveness. Disease Management. 2003;6(2):63. doi: 10.1089/109350703321908441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, et al. Meta-analysis: Chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;143:427–438. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorig K, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Medical Care. 2001;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorig K, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization. Medical Care. 1999;37:5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(6):256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman S, Steed L, Mulligan K. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. The Lancet. 2004;364:1523–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Evidence Report and Evidence Based Recommendations: Chronic Disease Self Management for Diabetes, Osteoarthritis, Post-Myocardial infarction Care, and Hypertension. [Accessed July, 2007]; http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PrevntionGenInfo/Downloads/CDSM%20Report.pdf.

- 13.Morse JM. Exploring the gheoretical basis of nursing using advanced techniques of concept analysis. Advances in Nursing Science. 1995;17(3):31–46. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barlow J, Sturt J, Hearnshaw H. Self-management interventions for people with chronic conditions in primary care: Examples from arthritis, asthma and diabetes. Health Education Journal. 2002;61(4):365–378. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creer TL, Holroyd KA. Self-management. In: Baum A, Newman S, Weinman J, West R, McManus C, editors. Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grey M, Knafl K, McCorkle R. A framework for the study of self- and family management of chronic conditions. Nursing Outlook. 2006;54(5):278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH. [Accessed July 20, 2007];Chronic Care Model. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/ChronicConditions/AllConditions/Changes.

- 18.Wagner EH, Davis C, Schaefer J, von Korff M, Austin BT. A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: Are they consistent with the literature. Managed Care Quarterly. 1999;7(3):56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management and education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boekaerts M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M. Handbook of Self-Regulation. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the Self-Regulation of Behavior. NY: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Boekaerts M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M. Handbook of Self-Regulation. San Diego: Academic Press: Harcourt; 2002. On the structure of behavioral self-regulation; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holroyd KA, Creer TL. Self-Management of Chronic Disease: Handbook of Clinical Interventions and Research. Orlando: Academic Press, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karoly P. Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 44. 1993. Mechanisms of self-regulation: A systems view; pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodenheimer T. Helping patient improve their health-related behaviors: What system changes do we need? Disease Management. 2005;8(5):319–330. doi: 10.1089/dis.2005.8.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodenheimer T, Lorig KR, Holman HR, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jounal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chronic Care: Self-Management Guideline Team CCsHMC. [Accessed February, 2008];Chronic Care: Self-Management. www.cincinnatichildrens.org/syc/alpha/h/health-policy/ev-based/chronic-care.htm.

- 29.Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management of heart disease, arthritis, diabetes, asthma, bronchitis, emphysema and others. Palo Alto (CA): Bull; 2000. Living a healthy life with chronic conditions. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorig K, Ritter P, Gonzalez VM. Hispanic chronic disease self-management: A randomized community-based outcome trial. Nursing Research. 2003;52(6):361–369. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorig KR. Chronic Disease Self-Management. American Behavioral Scientist. 1996;39(6):676–683. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parry C, Coleman EA, Smith CE, Frank JC, Kramer AM. The Care Transitions Interventions: A patient-centered approach to ensuring effective transfers between sites of geriatric care. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2003;22(3):1–17. doi: 10.1300/J027v22n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic disease. The Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagner EH, Austin BT, von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams SG, Smith PK, Allan PF, Anzueto A, Pugh JA, Cornell JE. Systematic review of the Chronic Care Model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and management. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:551–561. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Center for the Advancement of Health. [Accessed January, 2008];Health Behavior Change in Managed Care: A Status Report Executive Summary. http://www.cfah.org/pdfs/health_execsumm.pdf.

- 37.Schilling LS, Grey M, Knafl K. The concept of self-management of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37(1):87–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schilling LS, Grey M, Knafl K. A review of measures of self-management of type 1 diabetes by youth and their parents. The Diabetes Educator. 2002;28(5):796–808. doi: 10.1177/014572170202800520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riegel B, Dickson VV, Goldberg LR, Deatrick JA. Factors associated with the development of expertise in heart failure self-care. Nursing Research. 2007;56(4):235–243. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280615.75447.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed March 28, 2008];NCHS Definitions. http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/datawh/nchsdefs/adl.htm.

- 41.Clark NM, Becker MH, Janz NK, Lorig KR, Bakowski W, Andereson L. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults: A review and questions for research. Journal of Aging and Health. 1991;3(1):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renpenning KM, Taylor SG, editors. Self-Care Theory in Nursing: Selected papers of Dorothea Orem. New York: Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorig KR. Self-management education: More than a nice extra. Medical Care. 2003;41(6):699–701. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000072811.54551.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorig KR. Taking patient ed to the next level. RN. 2003;66(12):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory, and Applications. NY: The Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tobin DL, Reynolds RVC, Holroyd KA, Creer TL. Self-management and social learning theory. In: Holroyd KA, Creer TL, editors. Self-Management of Chronic Disease: Handbook of Clinical Interventions and Research. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1986. pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thoughts & Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorig K, Ritter PL, Plant K. A disease-specific self-help program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;53(6):950–957. doi: 10.1002/art.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lorig KR, Mazonson PH, Holman HR. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health costs. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1992;36(4):439–446. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Fries JF. Long-term randomized controlled trials of tailored-print and small-group arthritis self-management interventions. Medical Care. 2004 Apr;42(4):346–354. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118709.74348.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: A randomized trial. Medical Care. 2006;44(11):964–971. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glasgow RE, Hiss RG, Anderson RM, et al. Report of the Health Care Delivery Work Group. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(1):124–130. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-j. The care transitions intervention. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2002;2 doi: 10.5334/ijic.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parry C, Kramer HM, Coleman EA. A qualitative exploration of a patient-centered coaching intervention to improve care transitions in chronically ill older adults. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2006;25 doi: 10.1300/J027v25n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.University of Colorado Health Sciences Center; Division of Health Care Policy and Research. An interdisciplinary team approach to improving transitions across sites of geriatric care. [Accessed February 14, 2008]; http://www.caretransitions.org/documents/manual.pdf.

- 59.Rodgers BL. Developing Nursing Knowledge: Philosophical Traditions and Influences. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feetham SL, Thomson EJ. Keeping the Individual and Family in Focus. In: Miller SM, MCDaniel SH, Rolland JS, Feetham SL, editors. Individual, Families, and the New Era of Genetics: Biopsychosocial Perspectives. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knafl GJ, Grey M. Factor analysis model evaluation through likelihood cross-validation. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2007;16:77–102. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knafl GJ, Knafl KA. Mixed models incorporating intra-familial correlation through spatial autoregression. Research in Nursing & Health. 2005;28:348–356. doi: 10.1002/nur.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ryan P. Patient Centered Intervention for Osteoporosis Supported by Training Grant from NINR T32 NR 07102. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryan P, Pumilia NJ, Henak B, Chang T. Evaluating performance usability of a tailored intervention. Computers Informatics in Nursing. 2007 doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181b21779. in review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sawin KJ, Cox AW, Metzfer . Transitions to adulthood. In: Allen PJ, Vessey JA, editors. Primary Care of the Child with a Chronic Condition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sawin KL, Bellin MH, Roux G, Buran CF, Brei TJ. The expereince of self-management in adolescent women with spina bifida. Rehabilitation Nursing. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2009.tb00245.x. in Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiss M. Weight Management in Post-partum Women: Reigner Award. Marquette University College of Nursing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Im E-O, Meleis AI. Situation-specific theories: Philosophical roots, properties, and approach. Advances in Nursing Science. 1999;22(2):11–24. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199912000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fawcett J, Watson J, Neuman B, Walker PH, Fitzpatrick JJ. On Nursing Theories and Evidence. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2001;33(2):115–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meleis AI. Theoretical Nursing: Development and Progess. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Botelho RH, Dudrak R. Home assessment of adherence to long-term medication in the elderly. The Journal of Family Practice. 1992;35(1):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Geest S, von Rentein-Kruse W, Steeman E, Degraeve S, Abraham IL. Compliance issues with the geriatric population: Complexity with aging. The Nursing Clinics of North America. 1998:467–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilbert A, Luszcz M, Owen N. Medication use and its correlates among the elderly. Australian Journal of Public Health. 1993;17(1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1993.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kane RL, Kane RA, Arnold SB. Prevention and the elderly: Risk factors. Health Services Research. 1985;19(6 Pt2):945–1006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ryan AA. Medication compliance and older people: A review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1999;36(2):153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(99)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simons LE. Identifying barriers to medication adherence in adolescent transplant recipients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(7):831–844. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aday L. At Risk in America: The Health and Health Needs of Vulnerable Populations in the United States. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equality in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(4):254–258. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Danziger S, Corcoran MSD, et al. Barriers to the employment of welfare recipients. Poverty Research and Training. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 80.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work strategies (NEWWS) Washington, D. C: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams D. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: The added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1999;896:588–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. The Health of Nations: Why Inequality is Harmful to Your Health. New York: The New Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, eds. In: Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Medicine Io, editor. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sin M-K, Kang D-H, Weaver M. Relationships of asthma knowledge, self-management, and social support in African American adolescents with asthma. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;42:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skinner TC, John M, Hampson SE. Social support and personal models of diabetes as predictors of self-care and well-being: A longitudinal study of adolescents with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25(4):257–267. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.4.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tieffenberg JA, Wood EI, Alonso A, Tossutti MS, Vicente MF. A randomized field trial of ACINDES: A child-centered training model for children with chronic illness (asthma and epilepsy) Journal of Urban Health. 2000;77(2):280–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02390539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ryan P, Weiss M, Cerns S, Csuka M. Using theory to develop and evaluate a tailored intervention. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007 in review. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ajzen I. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ajzen I, Albarracin D, Hornick . Predicting and change of health behavior: Applying the reasoned action approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, JJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and personal health behaviors. Thorofare, NJ: Charles B. Slack, Inc; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 92.DiClemente C, Kegler MC. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. SF, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Glasgow RE, Funnell MM, Bonomi AE, Diavis C, Beckham V, Wagner EH. Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(2):80–87. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gochman DS, editor. Handbook of Health Behavior Research II: Provider Determinants. New York: Plenum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gochman DS. Health Behavior: Emerging Research Perspectives. New York: Plenum Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Haynes B, Taylor DW, Sackett DL. Compliance in Health Care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: A decade Later. Health Education & Behavior. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nigg CR, Allegrante JJP, Ory M. Theory-comparison and multiple-behavior research: Common themes advancing health behavior research. Health Education Research. 2002;17(5):670–679. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pender NJ, Murdaugh C, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. Vol. 4. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lang; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene JK, McBee WL, editors. The Handbook of Health Behavior Change. 2. New York, New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH. Social Support Measurement and Intervention. NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Greene J, Yedidia MJ The Take Care to Learn Evaluation Collaborative. Provider behaviors contributing to patient self-management of chronic illness among underserved populations. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16:808–824. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jenerett CM, Phillips RCS. An examination of differences in intra-personal resources, self-care management, and health outcomes in older and younger adults with sickle cell disease. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research. 2006:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mancini JA, Bowen GL, Martin JA. Community social organization: A conceptual linchpin in examining families in the context of community. Family Relations. 2005;54(5):570–582. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shoor S, Lorig KR. Self-care and the doctor-patient relationship. Medical Care. 2002;40(4 Supplement):II-40–II-44. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Burckhardt CS. Educating patients: Self-management approaches. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2005;27(12):703–709. doi: 10.1080/09638280400009097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Coates VE, Boore JR. Self-management of chronic illness: Implications for nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1995;32(6):628–640. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(95)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley M, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease: A systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(15):1641–1649. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gage H, Hampson S, Skinner TC, et al. Educational and psychosocial programmes for adolescents with diabetes: Approaches, outcomes and cost-effectiveness. Patient Education and Counseling. 2004;53(3):333–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sobel DS. The cost-effectiveness of mind-body medicine interventions. Vol. 122. Elsevier Science; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Doldy D, Silfo E. Chronic disease self-management by people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds: Action planning and impact. Journal of Integrated Care. 2006;14(4):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 114.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Carmona R. [Accessed 2003/11/07];Health Literacy in America: The Role of Health Care Professionals. 2003 http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/news/speeches/ama061403.htm.

- 116.Institute of Medicine:Committee on Health Literacy: Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington D.C: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Paasche-Orlow MK, Schillinger D, Greene SM, Wagner EH. How health care systems can begin to address the challenge of limited literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:884–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf M. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(S1 ):S19–S26. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kovach CR, Cashin JR, Sauer L. Deconstruction of a complex tailored intervention to assess and treat discomfort of people with advanced dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;55(6):678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yoos HL, Kitzman H, Henderson C, et al. The impact of the parental illness representation on disease management in childhood asthma. Nursing Research. 2007;56(3):167–174. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000270023.44618.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Blanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Parcel GS, Bartlett EE, Bruhn JG. The role of health education in self-management. In: Holroyd KA, Creer TL, editors. Self-Management of Chronic Disease: Handbook of Clinical Interventions and Research. Orlando: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 123.The Centers for the Advancement of Health. [Accessed March, 2008];Essential Elements of Self-Management Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Medical Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]