Abstract

Background

Human rhinovirus (HRV) infections are a major cause of exacerbations in chronic respiratory conditions such as asthma and COPD, but HRV-induced immune responses of the lower airway are poorly understood. Earlier work examining cytokine release following HRV infection has focused on epithelial cells because they serve as the principal site of viral replication, and internalization and replication of viral RNA appears necessary for epithelial cell mediator release. However, during HRV infection, only a small proportion of epithelial cells become infected. As HRV-induced cytokine levels in vivo are markedly elevated, this observation suggests that other mechanisms independent of direct viral infection may induce epithelial cell cytokine release.

Objective

Our aim was to test for the importance of interactions between human bronchial epithelial cells and monocytic cells in the control of mediator release during HRV exposure.

Methods

In vitro models of HRV serotype-16 (HRV16) infection of primary human bronchial epithelial cells and human monocytic cells, in mono or co-culture, were used. We assessed HRV16- induced CXCL10 and CCL2 protein release via ELISA.

Results

Co-culture of human monocytic and bronchial epithelial cells promoted a synergistic augmentation of CXCL10 and CCL2 protein release following HRV16 challenge. Transfer of conditioned media from HRV16-treated monocytic cells to epithelial cultures induced a robust release of CXCL10 by the epithelial cells. This effect was greatly attenuated by type I interferon receptor blocking antibodies, and could be recapitulated by IFNα addition.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that epithelial CXCL10 release during HRV infection is augmented by a monocytic cell-dependent mechanism involving type I interferon(s). Our findings support a key role for monocytic cells in the amplification of epithelial cell chemokine production during HRV infection, and help explain how an inflammatory milieu is created in the lower airways even in the absence of extensive viral replication and epithelial infection.

Keywords: Monocytes/Macrophages, epithelial cells, rhinovirus, inflammation, cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are a primary cause of the common cold, and are frequently associated with exacerbations of chronic respiratory disorders such as asthma [1–3], cystic fibrosis [4], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [5]. HRV infections affect the upper and lower airways [6–8], and induce elevated levels of cytokines/chemokines (e.g. G-CSF, IL-1, CXCL8) in airway secretions that are associated with both increased leukocyte numbers and greater severity of respiratory symptoms [9–12]. For those with chronic respiratory conditions, respiratory infections that lead to lower airway inflammation can result in exacerbation of symptoms and considerable morbidity and health care costs [13, 14]. The immune reaction that occurs in the lower airway in response to HRV, however, remains poorly understood.

As epithelial cells serve as the primary site of HRV replication in the airway, numerous investigations have examined the response of human airway epithelial cells to HRV infection. Several studies have also examined HRV-induced pulmonary inflammation in mouse models using minor group HRV serotypes [15, 16]. However, the study of major group HRV serotypes, which constitute ~90% of known strains, has been largely confined to in vitro work with human cells because of the specificity of major group HRV serotypes for human ICAM-1, which is necessary for viral entry [17]. Although recent work has led to the development of a transgenic mouse with a chimeric mouse-human ICAM-1 for the study of major group HRV serotypes [16], most information on these viruses has come from infection of human cells in culture. In vitro studies using human airway epithelial cells challenged with HRV demonstrate increased production of inflammatory mediators including interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, CXCL8 (IL-8), IL-11), interferon-β, CXCL10 (IP-10), CXCL5 (ENA-78), granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), CXCL1 (GROα), and CCL5 (RANTES) [18–22]. Several reports have noted that the early expression of certain cytokines, such as CXCL8, may not be dependent on viral replication [18, 23]. Conversely, other studies have indicated that the secretion of many of these pro-inflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells appears to be dependent on the internalization and replication of viral RNA, as UV-inactivated HRV does not elicit a similarly strong response, whereas transfection of dsRNA does result in robust cytokine release [20–22].

Analysis of biopsies from the epithelium of HRV-infected human subjects, however, reveals an apparent complication in the model wherein epithelial cell infection is necessary for cytokine release. Although the above studies suggest that HRV-stimulated cytokine production by epithelial cells is dependent on the presence of replicative virus, only a very small proportion of cells in primary human cultures [24] or epithelium biopsies from human volunteers appear to be actively infected [25, 26]. Nonetheless, during in vivo HRV infection there are marked elevations in the concentrations of numerous inflammatory mediators that are believed to be produced primarily by epithelial cells [9–12]. These observations suggest that uninfected epithelial cells may also be producing pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, possibly as a result of a paracrine stimulus from adjacent airway cells.

In contrast to epithelial cells, previous reports indicate that internalization of HRV by monocytic cells (monocytes and alveoloar macrophages) does not result in a productive infection and does not cause cell death [27, 28]. As such, monocytic cells in the airway are poised to respond to the presence of HRV and may act as continuing sentinels during infection. Studies conducted in our laboratory and others have revealed that monocytes/macrophages are a source of immune modulators following HRV challenge, as HRV stimulates monocyte/macrophage production of type I interferons, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-α, CXCL8, CCL2 (MCP-1), and CXCL10 [27–32]. Studies in which HRV-induced release of CCL2 and CXCL10 from human blood monocytic cells and human alveolar macrophages were examined in parallel showed a similar cytokine response between the two cell types [29, 32], indicating the use of blood monocytic cells, as a more readily available source of immune cells, can be useful in the study of CCL2 and CXCL10 release in response to HRV.

The chemokine CCL2, or monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), was originally identified as a chemotactic factor for monocytes, but has since been shown to also attract activated T cells, NK cells, and basophils [33]. Our lab has examined CCL2 release by alveolar macrophages after experimental HRV infection of human volunteers, and found that CCL2 release is significantly increased after infection [34]. The cytokine CXCL10, or interferon-gamma inducible protein-10 (IP-10), is a chemotactic factor for CXCR3+ cells, including T lymphocytes and natural killer cells, and has become a focus of many studies due to its association with HRV-induced pathology [21, 32, 35]. CXCL10 levels are increased not only in airway secretions, but also systemically to levels not seen with other cytokines examined in human volunteers following experimental HRV infection [36]. Higher CXCL10 levels are also associated with higher viral titers and greater lymphocyte numbers in nasal secretions as well as an increase in the severity of respiratory symptoms [21]. Recently, serum CXCL10 measurements have also been proposed to be a clinically useful biomarker of virally-induced asthma exacerbations [35]. As both bronchial epithelial cells and monocytic cells are capable of releasing CXCL10 in response to HRV [21, 32], their close proximity in vivo allows for intercellular interactions between these two cell types that may enhance CXCL10 production elicited by HRV exposure.

Several studies support the importance of monocyte/macrophage-epithelial cell interactions in the production of various immune mediators [37–44], but the interaction between primary human bronchial epithelial cells and isolated human monocytic cells during the immune response to HRV has not yet been examined. Accordingly, the present work focused on defining the intercellular responses to HRV established by the two most abundant cell types found in the lower airway under homeostatic conditions, namely monocytic cells and bronchial epithelial cells, and sought to provide insight into the mechanisms by which airway inflammation is established upon HRV exposure. We tested the hypothesis that intercellular interactions between human monocytic and bronchial epithelial cells amplify cytokine production following HRV serotype-16 (HRV16) challenge, and that soluble factors in the intercellular environment, as opposed to direct monocytic-epithelial cell interactions, are sufficient to mediate the enhanced cytokine response. Our findings demonstrate that monocytic-epithelial cell co-cultures exhibit synergistic augmentation over mono-cultures of CXCL10 and CCL2 protein following exposure to major group HRV16. Furthermore, this work supports a model wherein HRV indirectly activates robust epithelial cell CXCL10 release through the production of type I IFNs by monocytic cells. Our findings suggest that monocytic/epithelial cell interactions may be an important factor in augmenting cytokine elaboration during HRV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Collagen IV was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). RosetteSep human monocyte enrichment cocktail was purchased from StemCell Technologies Inc. (Vancouver, BC). Anti-CD118 (anti-interferon receptor type I) was purchased from Endogen/Pierce (Rockford, IL), and the isotype control IgG2aκ was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Recombinant human IFNα2b (Intron A) was obtained from Schering (Kenilworth, NJ).

Human Bronchial Epithelial Cell Culture

Human bronchial epithelial cells were obtained by enzymatic digestion of surgical specimens of human bronchi or trachea from lung transplant donors, as previously described [20]. The experimental protocols were approved by the University of Wisconsin Human Subjects Health Sciences Review Board. Isolated epithelial cells (passage 1–4) were plated in serum-free bronchial epithelial cell growth medium containing supplements (complete BEGM; BEGM bullet kit; Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville, Inc., Walkersville, MD) at a density of 1.25 × 105 cells/ml (for wells with monocytic cells) or 2.5 × 105 cells/ml (for wells without monocytic cells; 1 ml/well) in 6-well tissue culture plates (Corning Inc.Costar, Acton, MA) that were coated with 50 µg/ml collagen IV. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, prior to the addition of monocytes, at which point the epithelial cell number doubled from the initial number plated as determined using a hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH; n=3). After 24–48 h incubation with stimulus the supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C to remove non-adherent cells, and either frozen for subsequent protein analysis or transferred to mono-cultures for analysis of soluble factors.

Human Monocytic Cell Culture

Human monocytes were isolated from heparinized human blood acquired from volunteer donors using protocols approved by the University of Wisconsin Human Subjects Health Sciences Review Board. Volunteer donors were categorized as having allergic asthma (N=2), exercise/occupational induced asthma (N=1), having allergic rhinitis with no asthma (N=7), or being healthy controls (N=1). Monocyte enrichment was achieved as previously described [11] using a negative selection antibody cocktail, RosetteSep. The resulting cell population consisting of adherent and non-adherent leukocytes was 85–95% CD14+ (n=4) as determined by flow cytometry. Analysis of the resulting cell populations present after purification indicates that the CD45+, CD14− cells present are 0.3–1.5% CD3+, and 0.4–1% CD19+, with the majority of CD14 negative cells located in the lymphocyte gate, as determined by forward and side scatter, but negative for CD4, CD8, CD3, CD19, and CD16. To further characterize the monocytes using flow cytometry, gating by forward and side scatter revealed that the cells in the monocyte gate were 87±7% CD14hi, HLADRhi, CD206lo, and 13±7%CD14mid, HLADRhi, CD206lo. Of the CD14+ cells, 6% were CD16+. These cells were resuspended in complete BEGM and plated in collagen IV-coated (50 µg/ml) 6-well tissue culture plates with or without epithelial cells at a density of 2.5 × 105 or 5.0 × 105 cells/ml (1ml/well) respectively. Following a 2 h incubation, cells were rinsed with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Mediatech, Herndon, VA), and medium was replaced with reduced hydrocortisone (0.001%) BEGM (1 ml/well). Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 prior to stimulation and were subsequently called monocytic cells. Following 24–48 h incubation with stimulus, supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C to remove non-adherent cells, and either frozen for subsequent protein analysis or transferred to mono-cultures of monocytic cells or epithelial cells for analysis of the effects of conditioned medium on CXCL10 elaboration.

Production and Purification of HRV16

HRV16 was grown in HeLa cells as previously described [45] and virions were purified from the infected cell lysate by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion and sedimentation through a sucrose-step gradient to remove contaminants. The yield of the HRV16 particles was measured by optical density, and the multiplicity of infection (MOI), which refers to the number of infectious HRV particles per cell (typically 1 infectious HRV particle per 300 total particles), was determined by measuring the infectivity of the virions in HeLa cell monolayers.

Detection of cytokine release by monocytic cells and epithelial cells

Human monocytes and epithelial cells were plated in 6-well plates as described above. Following overnight incubation, cells were pretreated with or without neutralizing antibodies as described in the figure legends and subsequently stimulated with control vehicle, HRV16, or recombinant cytokines for 48 h at 37°C. Following incubation, cell supernatants were harvested, centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and frozen at −80°C until analysis. The protein levels of CXCL10 and CCL2 were measured utilizing a two-step sandwich-type ELISA as previously described [46]. Recombinant protein, coating, and biotinylated antibodies were purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN) for CXCL10, and BD biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ) for CCL2. Streptavidin conjugated to a HRP polymer (POLY-HRP-40; Fitzgerald Industries, Concord, MA), was used to increase assay sensitivity. A one-component substrate, 3,3',5'5'-tetramethylbenzidine (BioFx Laboratories, Owings Mills, MD), was used for color development, and the reaction was stopped by addition of 0.18 M sulfuric acid. OD at 450 nm was determined with a ELx800 universal microplate reader, and data were analysed with Ascent Software (Thermo Labsystems, Vantaa, Finland). The concentration of protein in cell supernatants was calculated by comparison with a standard curve generated with known amounts of human cytokine. The assay sensitivity was 12.5 pg/ml for CXCL10, and 3.125 pg/ml for CCL2.

Cell Viability Assay

Human monocytes were resuspended in the serum-supplemented RPMI-based media and plated in 96-well tissue culture plates at a density of 1×106 cells/ml (0.1 ml/well). Cells were pretreated with neutralizing or isotype control antibodies followed by stimulation with control vehicle or virus for 24 h at 37°C. Following these incubations, an MTS assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). The quantity of product was measured by the amount of absorbance at 490 nm using an ELx800 ELISA Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc. Winooski, VT), and is directly proportional to the number of metabolically-active/viable cells.

Statistical Analysis

The measurements of CXCL10 were log-transformed for analysis. All comparisons were carried out using ANOVA models (one measurement per EC donor/monocytic cell donor combination) or mixed-effects ANOVA models (repeated measures per donor combination). A two-sided 5%-level test result was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of HRV16 on CXCL10 release by epithelial and monocytic cell mono-cultures and co-cultures

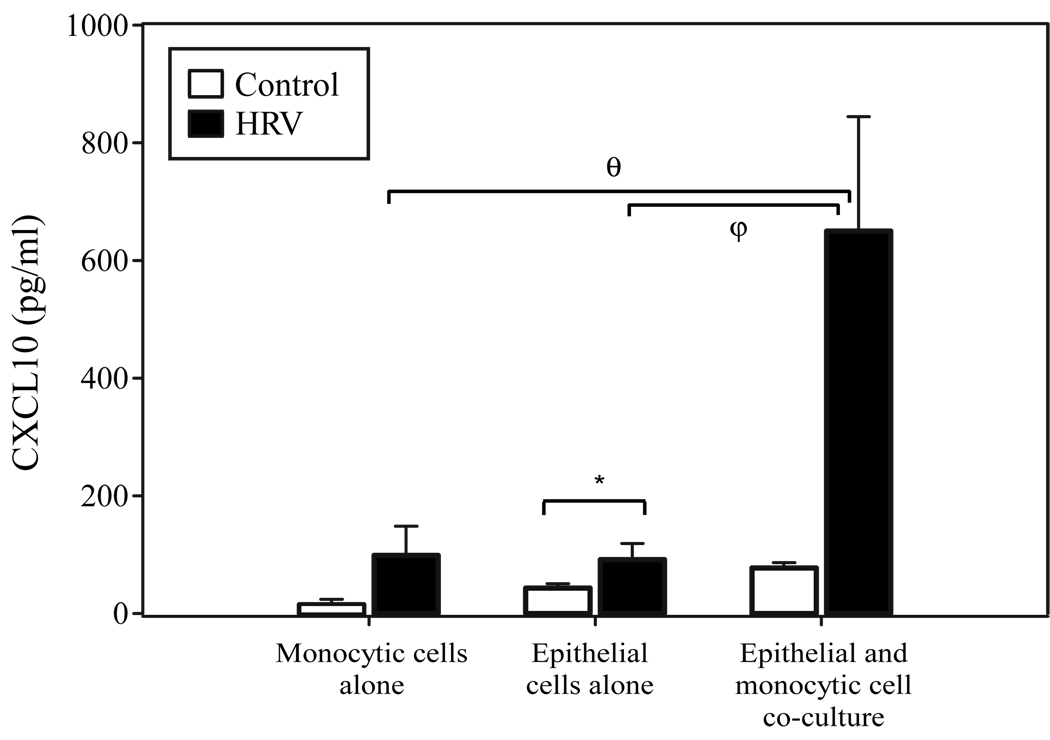

Under homeostatic conditions, the predominant cells on the luminal surface of the lower respiratory tract are epithelial cells and macrophages. To examine whether the release of CXCL10 observed in epithelial or monocytic cell cultures during HRV infection [21, 32] is affected by the simultaneous presence of the other cell population, we treated mono-cultures and co-cultures of primary human bronchial epithelial cells and peripheral blood monocytic cells with HRV16 and examined the supernatant for levels of the inflammatory cytokine CXCL10. Our previous findings had demonstrated that monocytic cells cultured in an RPMI based serum-supplemented medium respond robustly to HRV16 in release of CXCL10 [32], and we observed similar results in the present study (vehicle control = 62.8 ± 11 pg/ml, HRV16 = 26,400 ± 5,830 pg/ml; p < 0.0001 n=6, data not shown). Co-culture of monocytic cells and bronchial epithelial cells, however, necessitated the use of a defined, serum-free media, as the presence of serum has been shown to induce terminal squamous differentiation of human bronchial epithelial cells [47]. Monocytic cells exposed to HRV16 under serum-free conditions produce much smaller amounts of CXCL10, and these levels are comparable to that observed with bronchial epithelial cells treated with HRV under similar conditions (Fig. 1). Epithelial cells and monocytic cells cultured together in the presence of HRV16, however, resulted in a significant synergistic augmentation of CXCL10 production (Fig. 1). These data are consistent with a model of intercellular cooperation between epithelial cells and monocytic cells for the HRV-induced release of CXCL10.

Figure 1.

CXCL10 secretion from HRV16-simulated monocytic cell mono-cultures, epithelial cell mono-cultures, and epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures. Bronchial epithelial cells were plated at a density of 1.25 × 105 cells/ml (for co-culture) or 2.5 × 105 cells/ml (for mono-culture) in 6-well collagen-coated tissue culture plates. The following day monocytes were plated at a cell density of 5 × 105 cells/ml for mono-cultures and 2.5 × 105 cells/ml for epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures. Cells were incubated in reduced-hydrocortisone (0.001%HC) BEGM for 24 h prior to stimulation, then stimulated with vehicle control (HBSS + 0.1% BSA) or HRV16 (MOI = 10; resuspended in HBSS + 0.1% BSA) for 48 h (*, p= 0.05; φ, p < 0.03; θ, p < 0.004 by mixed-effects ANOVA). Data are summarized as the mean ± SEM from 6 experiments.

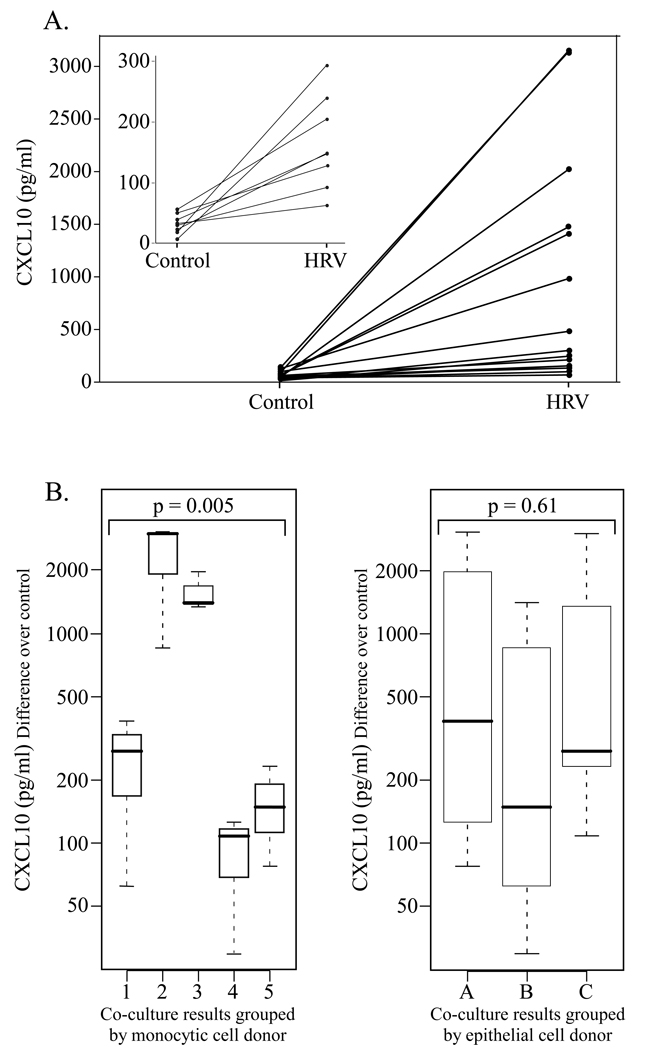

Variability in CXCL10 production by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures following HRV exposure

Although all co-cultures showed a synergistic enhancement of CXCL10 release, we noted a marked variability in the magnitude of the response. Therefore, to assess if CXCL10 expression was directed by phenotypic/functional characteristics of epithelial cells or that of monocytic cells, we conducted a comparison wherein epithelial cells from 3 donors were each paired with monocytic cells from 5 donors for a total of 15 co-culture populations. The amount of CXCL10 released in response to control or HRV16 is presented for each of the 15 co-culture experiments (Fig. 2A), with the inset magnifying the lowest responders. No significant differences in the CXCL10 response were detected when the co-culture results were grouped according to epithelial cell (EC) donor (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the magnitude of CXCL10 response differed significantly when the co-culture results were grouped according to the monocytic cell donor (Fig. 2B). If both EC donor and monocytic cell donor are included in the analysis, we find that the monocytic cell component of the co-culture explained most (84%) of the variance in CXCL10 responses, while the EC component contributed more modestly (8%). These data support the concept that phenotypic/functional features of monocytic cells influence the magnitude of CXCL10 elaboration by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures following HRV challenge.

Figure 2.

Examination of the variability in HRV-induced CXCL10 release according to cell type in co-culture. Human monocytic cells and bronchial epithelial cells were co-cultured and treated as described in Fig. 1. A. CXCL10 release by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures in response to control or HRV16 stimulation. Epithelial cells from 3 different donors and monocytic cells from 5 different donors were used to make 15 co-culture combinations, which showed variable CXCL10 release in response to HRV16. The inset magnifies the lower portion of the graph to show increased CXCL10 release in response to HRV16 for all co-cultures. B. HRV16-induced CXCL10 results from all 15 co-cultures plotted by donor cell type to examine the source of the variability. Control-treated CXCL10 values were subtracted from HRV16-treated for each epithelial/monocytic cell co-culture. On the left, results were plotted according to the monocytic cell donor, with each boxplot indicating CXCL10 release from co-cultures of 3 different EC donors with the same monocytic cell donor. On the right, the same 15 co-culture results were plotted according to the EC donor, with each boxplot indicating CXCL10 release from co-cultures of 5 different monocytic cell donors with the same EC donor.

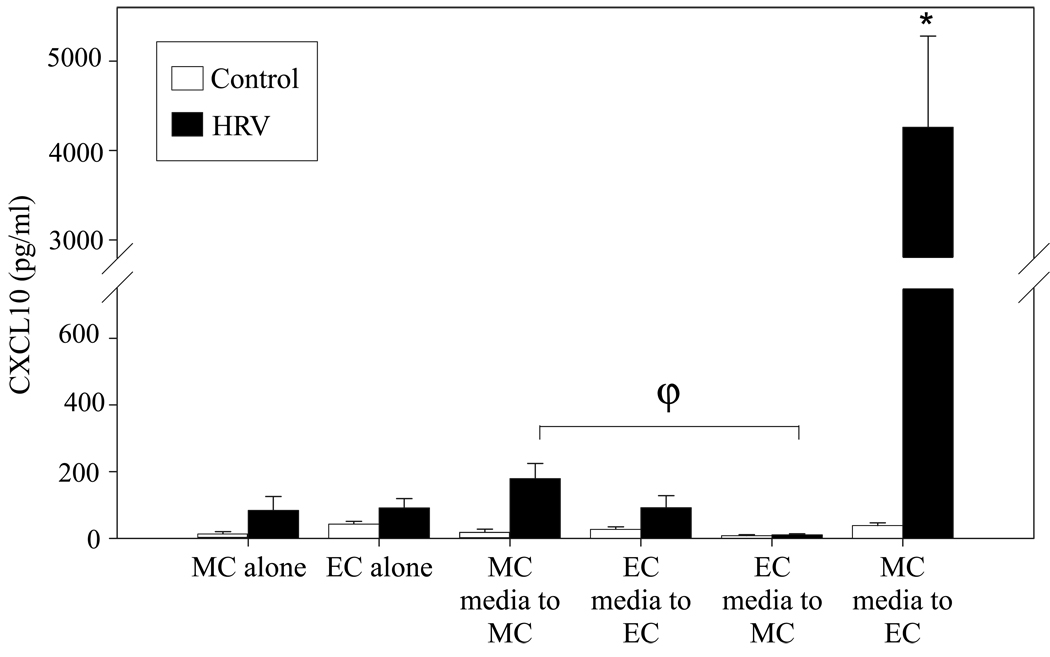

Effect of conditioned medium on CXCL10 production by epithelial and monocytic cell mono-cultures

To assess the nature of the cellular crosstalk responsible for the synergistic CXCL10 response seen in co-culture, a series of medium-transfer experiments were performed. Conditioned medium was transferred from a mono-culture of each cell type to a mono-culture of either the same or the other cell type to test the hypothesis that soluble factors released by monocytic cells in response to HRV stimulation enhance the production of CXCL10 by bronchial epithelial cells. Mono-cultures of primary monocytic and epithelial cells that did not undergo medium transfer were treated with HRV16 or control vehicle for comparison to conditioned medium transfers. Strikingly, epithelial cells incubated with medium from RV-treated monocytic cells displayed vigorous CXCL10 production. In comparison, considerably lower levels of CXCL10 were produced in response to other treatments/conditions, including a) mono-cultures of monocytic cells or epithelial cells following HRV16 challenge for 48 h, b) monocytic cells incubated with medium from HRV16 treated monocytic cells or medium from HRV16 treated epithelial cells, and c) bronchial epithelial cells incubated with medium from HRV16 treated epithelial cells (Fig. 3). All transfers of conditioned medium from HRV16 treated cells induced significantly more CXCL10 release than medium from control-treated cells (p < 0.05 for all pairs), however, only bronchial epithelial cells exposed to media conditioned by HRV16-treated monocytic cells produced a robust response. These data support the idea that one or more HRV-induced monocytic cell-derived soluble factors can mediate CXCL10 release by bronchial epithelial cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of cell-conditioned medium on CXCL10 production by epithelial and monocytic cells. Human bronchial epithelial cells and monocytic cells were plated in mono-culture as described in Fig. 1. After treatment with HRV16 (MOI=10) or vehicle control for 24 h, the cell-conditioned media was centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and then transferred to mono-cultures of the same or the other cell type. After 48 h, the supernatants were collected for analysis of CXCL10 protein concentration. In parallel, mono-cultures of epithelial cells and monocytic cells were exposed to control or HRV16 for 48 h. Release of CXCL10 protein by epithelial cell cultures that received conditioned medium from HRV16 treated monocytic cells was significantly increased over all other conditions. (*, p<0.015 by mixed-effects ANOVA for all comparisons; ϕ, p<0.03). EC = epithelial cell, MC = monocytic cell. Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 or more experiments.

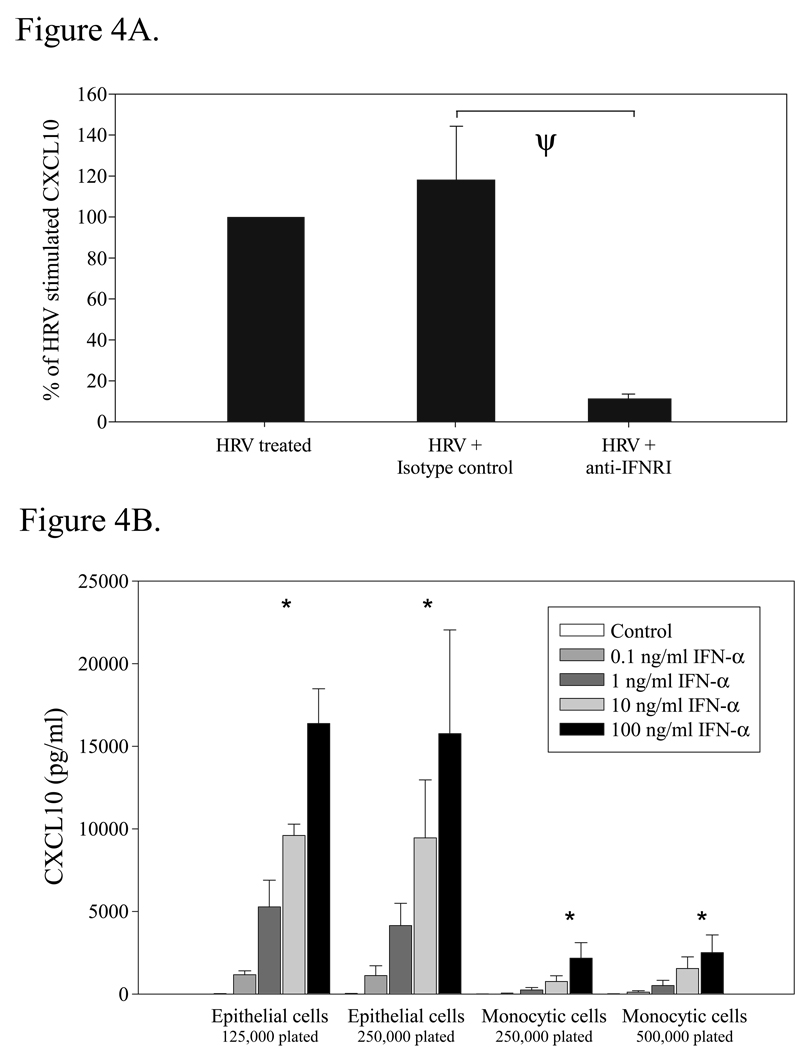

Neutralization of the type I IFN receptor attenuates HRV16-stimulated CXCL10 release by epithelial-macrophage co-cultures

We previously reported that type I IFN receptor ligation mediates HRV16-stimulated CXCL10 production by monocytes, thereby suggesting that this process is regulated by autocrine and paracrine action of type I IFNs [32]. Similarly, the present data support the idea that production of a soluble factor(s) by monocytic cells following HRV exposure promotes CXCL10 release from epithelial cells. Therefore, we tested the concept that intermediate production of type I IFNs also regulates the synergistic augmentation of CXCL10 by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures following HRV16 challenge. As shown in Fig. 4A, we observed that blocking the type I IFN receptor by pre-treatment of epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures with an anti-IFN receptor type I antibody (anti-IFNRI) significantly suppressed HRV16-induced CXCL10 production. Conversely, treatment with an isotype control antibody (IgG2aκ) had no significant effect on HRV16-induced CXCL10 release (Fig. 4A). The decrease in CXCL10 release by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures in the presence of anti-IFNRI did not appear to be the result of cytotoxic effects, as mean cell viability was 105 ± 7 % relative to control treatment (n = 4). These findings support the idea that HRV16-induced CXCL10 release by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures is mediated by autocrine and paracrine action of type I IFNs.

Figure 4.

Role of type I interferons in HRV-induced CXCL10 release by epithelial and monocytic cells. Human bronchial epithelial cells and monocytic cells were plated in co-culture (A) or mono-culture (B) as described in Fig. 1. A. Co-cultures were pretreated with isotype control (IgG2aκ; 5 µg/mol) or anti-IFN receptor type I blocking antibody (anti-IFNRI; 5 µg/mol) for 30 min, then stimulated with vehicle control (HBSS + 0.1% BSA) or HRV16 (MOI = 10) for 48 h. (ψ, p<0.0001 for comparison to HRV + IgG by mixed-effects ANOVA). The data represent the percent of CXCL10 released compared to HRV16-treated cells ± SEM of % treated from 4 independent experiments. B. Epithelial and monocytic cells were plated to reflect the cell numbers present during mono or co-culture experiments, with half the number of each cell type present in co-culture in order to keep total cell number constant. Cells were treated with vehicle control (HBSS + 0.1% BSA) or doses of the type I interferon IFNα2b ranging from 0.1–100 ng/ml (resuspended in HBSS + 0.1% BSA), and then incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The dose response was significant within all conditions (*, p<0.0001 by mixed-effects ANOVA), and between epithelial cell and monocytic cell responses (p<0.0001 by mixed-effects ANOVA). Data represent mean ± SEM from 4 experiments.

Effect of a type I interferon on CXCL10 release in monocytic cells and bronchial epithelial cells

As blockade of the type I interferon receptor largely abrogated CXCL10 release, we examined if exposure to type I interferons was sufficient for the magnitude of CXCL10 release observed in our in vitro system. Mono-cultures of monocytic cells and bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to several concentrations of recombinant human IFNα2b (Fig. 4B) which spanned the measured quantity of IFNα released by monocytes exposed to HRV16 in vitro under serum-supplemented conditions [32]. Whereas CXCL10 release increased for both cell types in a dose-dependent manner, bronchial epithelial cells produced more CXCL10 in response to IFNα than monocytic cells (Fig. 4B), and suggests that in our culture conditions, type I IFNs may be present in the 0.1–1 ng/ml range as evidenced by the magnitude of CXCL10 release. These data support the idea that a type I interferon can induce CXCL10 production in a dose-dependent manner in monocytic cells and bronchial epithelial cells.

Examination of HRV16-induced release of CCL2 in bronchial epithelial and monocytic cell cultures

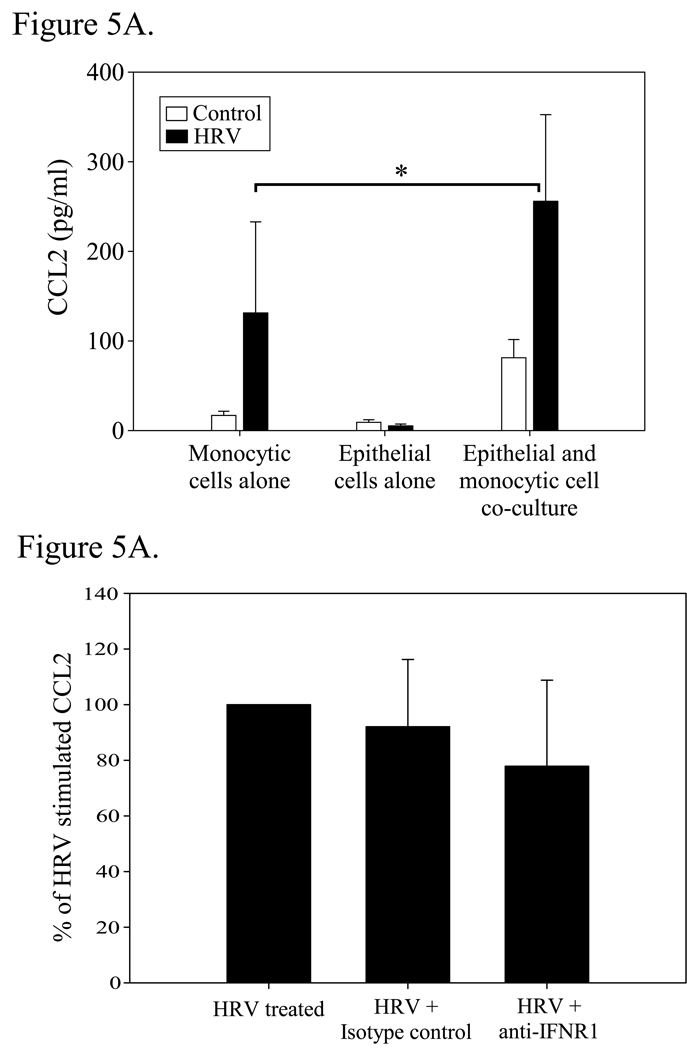

Because a synergistic release of CXCL10 protein was observed when monocytic and airway epithelial cells were co-cultured, we hypothesized that additional HRV-sensitive chemokines are increased when these cells are co-cultured. In this regard, we and others have shown that monocytic and bronchial epithelial cells release CCL2 in response to viral exposure [29, 48], and CCL2 induction has been reported to be dependent on the effect of type I interferons after viral stimulation [49]. Therefore, we examined CCL2 levels in the culture supernatants. As shown in Fig. 5A, CCL2 was significantly increased in monocytic-epithelial cell co-culture over mono-culture following HRV16 stimulation. Antibody blockade of the type I interferon receptor did not, however, significantly reduce CCL2 (Fig 5B), suggesting that, as opposed to CXCL10, HRV-induced CCL2 release is not highly dependent on IFNR1 ligation.

Figure 5.

Secretion of CCL2 (MCP-1) by epithelial/monocytic cell mono and co-cultures in response to HRV16. A. Bronchial epithelial cells and monocytic cells were plated in mono or co-culture as described in Fig. 1, and treated with vehicle control or HRV16 for 48h. Supernatants were analysed for the presence of CCL2 by ELISA. (*, p=0.05). Data represent mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. B. Effect of type I interferon receptor blockade on the release of CCL2. Co-cultures were treated as described in 4A, and then examined for CCL2 levels by ELISA after 48h. Data are expressed as the percent of CCL2 released from HRV16-treated cells ± SEM of % treated from 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The close proximity of macrophages and airway epithelial cells in vivo suggests that interactions between these two cell types may play an important role in regulating cytokine production profiles in response to various immunological stimuli. The present study is the first to demonstrate that the intercellular crosstalk between isolated human monocytic cells and primary human bronchial epithelial cells has a profound effect on HRV-induced CXCL10 elaboration, as evidenced by the observation that monocytic/bronchial epithelial cell co-cultures exhibit synergistic augmentation of CXCL10 production following in vitro HRV16 challenge. Our data indicates that a soluble factor produced by the monocytic cell component of the co-culture, as opposed to the epithelial cell component, significantly influences HRV-induced CXCL10 release. Additionally, antibody-mediated blockade of the type I interferon receptor strongly attenuates HRV16-stimulated CXCL10 release by epithelial-monocytic cell co-cultures. These data support a model wherein HRV indirectly activates epithelial cells for the release of CXCL10 protein through a monocytic cell-dependent mechanism involving, at least in part, the release and autocrine/paracrine action of type I interferon(s).

It is interesting to note that in our media transfer and co-culture experiments, incubation of epithelial cells with conditioned media from HRV16-stimulated monocytic cells resulted in substantially more CXCL10 production than what was produced by co-cultures following HRV16 challenge (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). Although differing epithelial cell numbers can account for some of the response seen (mono-culture of 5×105 epithelial cells/well for medium transfer, vs. 2.5×105 epithelial cells/well in co-culture), the difference in magnitude is such that other mechanisms are likely involved. In co-culture, mediators that are rapidly metabolized (e.g. nucleotides, lipid mediators) may inhibit CXCL10 release when in close proximity, but may not persist in the medium transfer experiments. Cell contact between epithelial cells and monocytic cells may also transduce signals that suppress CXCL10 production or release. Evidence suggests that airway epithelial cells express membrane-associated TGF-β that continuously inhibits alveolar macrophages in a contact-dependent manner [50], which would be present in a co-culture, but not in a medium transfer setting. Lung epithelial cells have also been shown to release inhibitory soluble factors that decrease LPS-induced inflammatory responses in alveolar macrophages [51]. In our studies, we saw evidence of an inhibitory soluble factor as well, as epithelial cell-conditioned medium acted to suppress CXCL10 release by monocytic cells (Fig. 3: monocytic cells incubated with MC-conditioned medium vs. monocytic cell with EC-conditioned medium, p< 0.03 from HRV stimulated cells). As the lung has been suggested to have an immunosuppressive microenvironment [52, 53], these observations are consistent with concurrent anti-inflammatory responses that may occur even during an active infection. The present studies also support the concept that the experimental use of mono-cultures may not fully describe the physiologically-relevant responses that occur in vivo to respiratory viruses, as intercellular interactions can alter the observed immune response.

It is noteworthy that the present epithelial cell data differ from previous findings in regard to the amount of CXCL10 protein released following HRV16 challenge. Although there was a reproducible and significant increase in epithelial cell CXCL10 production in response to HRV16 (p=0.05), the magnitude is modest in comparison to the levels previously reported [21, 35]. Earlier studies have suggested that infection and viral replication in bronchial epithelial cells is necessary for HRV-induced mediator release by epithelial cells [20, 21]. The smaller magnitude of chemokine release in our epithelial cell cultures may result from a lower rate of HRV replication, as our cultures were incubated at a higher temperature (37°C) than that used in other studies, and one that may be less optimal for HRV replication in bronchial epithelial cells [20]. Preliminary analysis of HRV RNA by qPCR also indicates that little viral replication was occurring in our epithelial cultures (47×106 copies of viral RNA at time zero; 13×106 copies for epithelial cells at 24 h; and 161×106 copies in HeLa cells at 24 h as a positive control). However, a smaller proportion of cultured cells with active infection may be a reasonable in vitro model for the airway, as studies have shown that only small subsets of respiratory epithelium are HRV-infected in vivo [26]. In vitro studies using epithelial cells grown at an air/liquid interface also indicate that differentiated epithelial cell cultures have a lower rate of infection than traditional submerged undifferentiated cultures, as HRV infects only 1% of cells in fully differentiated cultures [24]. Lower CXCL10 release in our cultures was specific to HRV, as epithelial cells cultured under the described conditions were capable of responding robustly to stimuli such as IFNα, IFNγ, TNFα, and supernatants from macrophages-exposed to HRV16 (Fig. 3, Fig. 5, and unpublished data).

Our data supports current opinion that epithelial cells are the primary source of CXCL10 during HRV infection, but suggests that direct viral exposure may be a minor factor in the in vivo epithelial cytokine response. A larger contributor may be the paracrine release of cytokines from HRV-stimulated monocytic cells, allowing uninfected epithelium to participate in the immune response as well. These data suggest that monocytic cells are likely a very important component to HRV-induced inflammation, and one that has been not well studied. Although monocytic cells are capable of robustly releasing CXCL10 under serum supplemented conditions, and may be producing high levels of HRV-induced CXCL10 in vivo, our data indicate that they would also be releasing type I interferons. As the density of epithelial cells is much higher than the density of alveolar macrophages in the airway, the cumulative amount of epithelial cell IFN-induced CXCL10 is likely to substantially contribute to its overall level in the airway.

A key issue in this analysis pertains to how the present culture conditions relate to physiological conditions and whether the amount of CXCL10 released by monocytic cells under serum-free conditions is representative of how much CXCL10 is released from these cells in vivo. Indeed, our study revealed a substantial difference in the amount of CXCL10 released by monocytic cells cultured in serum-supplemented media and under serum-free conditions. In this regard, although serum-supplementation may reflect certain conditions in the blood, serum-free conditions are important to assess, since in vivo alveolar macrophages and bronchial epithelial cells are not submerged in serum in the airway. As such, both serum-supplemented and serum-free culture conditions provide valuable information in studying cellular responses to HRV, as they emulate different physiological compartments.

Besides assessing CXCL10 production by epithelial-monocytic cell co-culture, we also noted that CCL2 levels were synergistically increased in co-culture following HRV treatment (Fig. 5A), but that IFNR1 blockade did not substantially reduce CCL2 release as it did for CXCL10 release (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5B). Although type I interferons have been implicated in CCL2 release in response to other viruses [49], our data suggests that additional factors may be critical for HRV-induced CCL2 release. In our system there is no direct evidence that epithelial cells are producing CCL2, since HRV16-induced CCL2 release from monocytic cells alone (131±101 pg/ml, Fig. 5A) was similar in magnitude to levels of CCL2 measured from epithelial cells treated with conditioned media from HRV-treated monocytic cells (99±21 pg/ml, data not shown), and may simply represent CCL2 already present in the conditioned media. We have previously shown that HRV-induced CCL2 release by monocytes and macrophages is increased as early as 4 h after HRV exposure [29]. In contrast, HRV-induced CXCL10 release by mono-cultures of human monocytic and bronchial epithelial cells is not substantially increased until 24 h after virus addition [21, 32]. These time frames suggest that HRV-induced CCL2 release may occur via both direct and autocrine mechanisms, whereas CXCL10 release is significantly affected by an HRV-induced intermediate factor that acts to augment CXCL10 production. Our data support this idea, as CXCL10 in our cultures is produced primarily by epithelial cells exposed to soluble factors released by HRV-treated monocytic cells (Fig. 3), and CCL2 release is seen even in mono-cultures of monocytic cells exposed to HRV16 (Fig. 5A). CCL2 levels are increased in co-culture, however, indicating epithelial cells may be acting on monocytic cells to augment CCL2 release in contrast to the mechanism for CXCL10 release in co-culture. While the differences in the regulation of CXCL10 and CCL2 suggested by our data adds to our knowledge of HRV-induced inflammation, examination of other cytokines and their regulation will be necessary to further our understanding of anti-viral inflammatory pathways of the airway.

Our observations support the idea that responses to HRV are multi-cellular and interactive. The data indicate that epithelial-monocytic cell interactions result in synergistic augmentation and release of CXCL10 and CCL2 protein following HRV challenge, and suggest that phenotypic/functional features of monocytic cells direct the CXCL10 synergistic response, at least in part, through the release of soluble factors including type I interferons. Inflammatory responses heightened by cytokine cross-talk between cells such as seen in our studies could be an explanation as to how an inflammatory milieu is created in the lower airways even in the absence of extensive viral replication and epithelial infection, and provide a potential target for limiting pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Further understanding of the multi-cellular immune response to HRV will help in the design of new therapies to decrease rhinovirus-induced pro-inflammatory events, in the hopes of controlling lower airway inflammation and reducing the frequency and severity of HRV-induced exacerbations in asthma, cystic fibrosis, and COPD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to several individuals affiliated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison including Drs. James Gern and Wai Ming Lee for preparation of virus stocks, Rebecca Brockman-Schneider for help with bronchial epithelial cell culture, Dr. Nizar Jarjour for providing the CCL2 and CXCL10 ELISA reagents, and Dr. Julie Sedgwick for preparation of PBMCs.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants U19 AI070503, R01 HL069116, P01 AI50500, MolRR03186, and T32 HD041921.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pattemore PK, Johnston SL, Bardin PG. Viruses as precipitants of asthma symptoms. I. Epidemiology. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22:325–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb03094.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory viruses and exacerbations of asthma in adults. Bmj. 1993;307:982–986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6910.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston SL, Pattemore PK, Sanderson G, et al. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9–11 year old children. Bmj. 1995;310:1225–1229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collinson J, Nicholson KG, Cancio E, et al. Effects of upper respiratory tract infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 1996;51:1115–1122. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.11.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seemungal TA, Harper-Owen R, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Detection of rhinovirus in induced sputum at exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:677–683. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16d19.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser L, Aubert JD, Pache JC, et al. Chronic rhinoviral infection in lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1392–1399. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-489OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gern JE, Galagan DM, Jarjour NN, Dick EC, Busse WW. Detection of rhinovirus RNA in lower airway cells during experimentally induced infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1159–1161. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadopoulos NG, Bates PJ, Bardin PG, et al. Rhinoviruses infect the lower airways. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1875–1884. doi: 10.1086/315513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarjour NN, Gern JE, Kelly EA, et al. The effect of an experimental rhinovirus 16 infection on bronchial lavage neutrophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1169–1177. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proud D, Gwaltney JM, Jr, Hendley JO, et al. Increased levels of interleukin-1 are detected in nasal secretions of volunteers during experimental rhinovirus colds. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1007–1013. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner RB, Weingand KW, Yeh CH, Leedy DW. Association between interleukin-8 concentration in nasal secretions and severity of symptoms of experimental rhinovirus colds. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:840–846. doi: 10.1086/513922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gern JE, Vrtis R, Grindle KA, Swenson C, Busse WW. Relationship of upper and lower airway cytokines to outcome of experimental rhinovirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2226–2231. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2003019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1608–1613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proud D, Chow CW. Role of viral infections in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:513–518. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0199TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newcomb DC, Sajjan US, Nagarkar DR, et al. Human rhinovirus 1B exposure induces phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent airway inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1111–1121. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1243OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartlett NW, Walton RP, Edwards MR, et al. Mouse models of rhinovirus-induced disease and exacerbation of allergic airway inflammation. Nat Med. 2008;14:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nm1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greve JM, Davis G, Meyer AM, et al. The major human rhinovirus receptor is ICAM-1. Cell. 1989;56:839–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90688-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griego SD, Weston CB, Adams JL, Tal-Singer R, Dillon SB. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in rhinovirus-induced cytokine production by bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:5211–5220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terajima M, Yamaya M, Sekizawa K, et al. Rhinovirus infection of primary cultures of human tracheal epithelium: role of ICAM-1 and IL-1beta. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L749–L759. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroth MK, Grimm E, Frindt P, et al. Rhinovirus replication causes RANTES production in primary bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:1220–1228. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spurrell JC, Wiehler S, Zaheer RS, Sanders SP, Proud D. Human airway epithelial cells produce IP-10 (CXCL10) in vitro and in vivo upon rhinovirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L85–L95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Hamati E, Lee PK, et al. Rhinovirus Induces Airway Epithelial Gene Expression through Double-Stranded RNA and IFN-Dependent Pathways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:192–203. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0417OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaul P, Biagioli MC, Singh I, Turner RB. Rhinovirus-induced oxidative stress and interleukin-8 elaboration involves p47-phox but is independent of attachment to intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and viral replication. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1885–1890. doi: 10.1086/315504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Souza N, Dolganov G, Dubin R, et al. Resistance of differentiated human airway epithelium to infection by rhinovirus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L373–L381. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arruda E, Boyle TR, Winther B, et al. Localization of human rhinovirus replication in the upper respiratory tract by in situ hybridization. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1329–1333. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosser AG, Brockman-Schneider R, Amineva S, et al. Similar frequency of rhinovirus-infectible cells in upper and lower airway epithelium. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:734–743. doi: 10.1086/339339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gern JE, Dick EC, Lee WM, et al. Rhinovirus enters but does not replicate inside monocytes and airway macrophages. J Immunol. 1996;156:621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston SL, Papi A, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. Rhinoviruses induce interleukin-8 mRNA and protein production in human monocytes. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:323–329. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall DJ, Bates ME, Guar L, et al. The Role of p38 MAPK in Rhinovirus-Induced Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Production by Monocytic-Lineage Cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:8056–8063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stockl J, Vetr H, Majdic O, et al. Human major group rhinoviruses downmodulate the accessory function of monocytes by inducing IL-10. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:957–965. doi: 10.1172/JCI7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laza-Stanca V, Stanciu LA, Message SD, et al. Rhinovirus replication in human macrophages induces NF-kappaB-dependent tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Virol. 2006;80:8248–8258. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00162-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korpi-Steiner NL, Bates ME, Lee WM, Hall DJ, Bertics PJ. Human rhinovirus induces robust IP-10 release by monocytic cells, which is independent of viral replication but linked to type I interferon receptor ligation and STAT1 activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1364–1374. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0606412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu L, Tseng SC, Rollins BJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Chem Immunol. 1999;72:7–29. doi: 10.1159/000058723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bates ME, Korpi NL, Hall DJ, Heuser RL, Aga M, Busse WW, Bertics PJ. Human Bronchoalveolar (BAL) Cells Secrete Increased Amounts of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 (MCP-1) During an Experimental Rhinovirus (RV) Infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:S316. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wark PA, Bucchieri F, Johnston SL, et al. IFN-gamma-induced protein 10 is a novel biomarker of rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kakumanu S, Evans MD, Busse WW, Gern JE. Infection with rhinovirus induces a systemic IP-10 response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:S114. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tao F, Kobzik L. Lung macrophage-epithelial cell interactions amplify particle-mediated cytokine release. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:499–505. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.4.4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujii T, Hayashi S, Hogg JC, et al. Interaction of alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells following exposure to particulate matter produces mediators that stimulate the bone marrow. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:34–41. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.27.1.4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishii H, Hayashi S, Hogg JC, et al. Alveolar macrophage-epithelial cell interaction following exposure to atmospheric particles induces the release of mediators involved in monocyte mobilization and recruitment. Respir Res. 2005;6:87. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torvinen M, Campwala H, Kilty I. The role of IFN-gamma in regulation of IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) expression in lung epithelial cell and peripheral blood mononuclear cell co-cultures. Respir Res. 2007;8:80. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Phan SH, Rollins BJ, Strieter RM. Alveolar macrophage-derived cytokines induce monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression from human pulmonary type II-like epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9912–9918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii H, Fujii T, Hogg JC, et al. Contribution of IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha to the initiation of the peripheral lung response to atmospheric particulates (PM10) Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L176–L183. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00290.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Psarras S, Volonaki E, Skevaki CL, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated induction of angiogenesis by human rhinoviruses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xatzipsalti M, Psarros F, Konstantinou G, et al. Modulation of the epithelial inflammatory response to rhinovirus in an atopic environment. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:466–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee WM, Wang W. Human rhinovirus type 16: mutant V1210A requires capsid-binding drug for assembly of pentamers to form virions during morphogenesis. J Virol. 2003;77:6235–6244. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6235-6244.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly EA, Rodriguez RR, Busse WW, Jarjour NN. The effect of segmental bronchoprovocation with allergen on airway lymphocyte function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1421–1428. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.5.9703054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lechner JF, Haugen A, McClendon IA, Shamsuddin AM. Induction of squamous differentiation of normal human bronchial epithelial cells by small amounts of serum. Differentiation. 1984;25:229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1984.tb01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Casola A, Saito T, et al. Cell-specific expression of RANTES, MCP-1, and MIP-1alpha by lower airway epithelial cells and eosinophils infected with respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 1998;72:4756–4764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4756-4764.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hokeness KL, Kuziel WA, Biron CA, Salazar-Mather TP. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and CCR2 interactions are required for IFN-alpha/beta-induced inflammatory responses and antiviral defense in liver. J Immunol. 2005;174:1549–1556. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takabayshi K, Corr M, Hayashi T, et al. Induction of a homeostatic circuit in lung tissue by microbial compounds. Immunity. 2006;24:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubovitch V, Gershnabel S, Kalina M. Lung epithelial cells modulate the inflammatory response of alveolar macrophages. Inflammation. 2007;30:236–243. doi: 10.1007/s10753-007-9042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bingisser RM, Holt PG. Immunomodulating mechanisms in the lower respiratory tract: nitric oxide mediated interactions between alveolar macrophages, epithelial cells, and T-cells. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131:171–179. doi: 10.4414/smw.2001.09653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raychaudhuri B, Fisher CJ, Farver CF, et al. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)-mediated inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production by human alveolar macrophages. Cytokine. 2000;12:1348–1355. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]