Abstract

Increased apoptotic cell death is believed to play a pathological role in septic patients and experimental animals. Apoptosis can be induced by either a cell death receptor (extrinsic) or mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway. Bid, a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family, is thought to mediate cross talk between the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis; however, little is known about the action of Bid in the development of apoptosis and organ specific tissue damage/cell death as seen in polymicrobial sepsis. Our results show that following the onset of sepsis, tBid (the active form of Bid) is significantly increased in mitochondrial fractions of the thymus, spleen, Peyer’s patches and liver and that Fas or FasL deficiency blocks Bid activation in various tissues after septic challenge. Increased Bid activation is correlated with increased active caspase-3, -9 and apoptosis during sepsis. Bid deficient mice exhibit significantly reduced apoptosis in the thymus, spleen and Peyer’s patches compared with background mice after sepsis. Furthermore, Bid deficient mice had significantly reduced systemic and local inflammatory cytokine levels and improved survival after sepsis. These data support not only the contribution of Bid to sepsis-induced apoptosis and the onset of septic morbidity/mortality, but also the existence of a bridge between extrinsic apoptotic signals, e.g., FasL:Fas, TNF:TNFR, etc., and the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway via Bid-tBid activation during sepsis.

Keywords: Fas-FasL, cytokine, chemokine, Bcl-2, mice

INTRODUCTION

The inability of present therapies to mitigate the devastating effects of sepsis and multiple organ failure in the critically ill patient indicates that more knowledge of the pathophysiology of sepsis is needed to develop effective interventions (1). Programmed cell death, or apoptosis not only is critical for the development and homeostasis in the immune and central nervous systems of many organisms (2), but also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of many diseases, such as HIV immune depression, cancer, autoimmune disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, inflammatory bowel disease and ischemic injury (3). Over the past decade, growing evidence suggests that apoptosis plays a crucial role in the outcome of experimental animals and patients with sepsis. The increased apoptosis occurring during sepsis suggests a loss of immune and/or nonimmune cell populations, thereby contributing to immunosuppression and subsequent multiple organ failure (4, 5). Most consistently, increased lymphoid apoptosis has been found in a variety of tissue sites after sepsis; importantly, inhibition of lymphocyte apoptosis has been shown to improve survival in animal models of sepsis (6–9). Studies have also shown that mice lacking functional lymphocytes (i.e., RAG−/− (10) or γδT −/− mice (11)) had a higher mortality when subjected to sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP).

There are two major apoptotic pathways in mammalian cells: cell death receptor (extrinsic) and mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathways. The extrinsic pathway is triggered by death receptors, including Fas (CD95 or APO-1), tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1), DR3 (APO-3), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (TRAILR)1 (DR4) and TRAILR2 (DR5). Engagement of these receptors with their ligands recruits the Fas associated death domain (FADD), or TNF Receptor I associated death domain (TRADD), procaspase-8 (FADD-like IL- 1 -converting enzyme [FLICE]), etc. to form a death –inducing signaling complex (DISC). This complex can activate caspase-8, which in turn cleaves and activates a signaling cascade of downstream proteases including caspase-3, -6 or 7, leading to apoptosis (12).

The intrinsic mitochondrial pathway is regulated by B-cell CCl/lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family members that include both anti-apoptotic (e.g. Bcl-2 and Bcl-2XL) and pro-apoptotic proteins. All of the members share up to four conserved Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains 1–4. Pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 members are further divided into multiple BH domain-containing proteins, such as Bax and Bak, and BH-3 only proteins, such as Bid, Bim, and Bad, etc. In response to various stress stimuli, pro-apoptotic members are activated and induce the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane where they provoke permeability transition and the release of apoptogenic factors including cytochrome C. Cytosolic cytochrome C binds to apoptosis protease activating factor-1 (Apaf-1), which activates procaspase-9 and subsequently initiates a downstream caspase cascade resulting in cell death (13).

Although these two apoptotic pathways can act independently, it appears that there is cross talk between the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. It has been proposed that FasL-Fas driven “extrinsic-” or “-intrinsic-” apoptosis depends on whether or not it takes place in a type I or type II cell (14). Type I cells (e.g. B-lymphoblasts) appear to activate large amount of caspase-8 by the DISC and directly activate downstream caspase-3 and/or other proteases resulting in apoptosis. These cells bypass the mitochondria in Fas-mediated apoptosis, which cannot be blocked by Bcl-2 overexpression (15). Alternatively, type II cells (e.g. Jurkat T– cells or hepatocytes) appear to produce less active caspase-8, and the mitochondria are needed to trigger downstream caspase activation for apoptosis, which can be inhibited by Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL (14). The nature of the transition of apoptotic signals from death receptors to the mitochondria became clear when Bid protein was discovered. Upon the engagement of death receptors and their ligands, caspase-8 is activated and cleaves cytoplasmic Bid into truncated Bid (tBid), which then translocates to the mitochondria where it promotes Bax and Bak activation and the subsequent intrinsic death pathway (16). Studies have shown that hepatocytes lacking Bid are resistant to Fas or TNF-α induced-cell death (17, 18). Furthermore, wild type mice treated with Fas agonist antibody (clone Jo2) exhibited massive hepatocyte apoptosis and severe liver injury; a response not observed in bid-deficient mice (17). Several studies, including ours, have demonstrated that immune cell apoptosis is increased in a variety of tissue sites during sepsis (4, 19–21), and that organ damage and mortality associated with sepsis in mouse models are at least in part due to the activation of the Fas-FasL signaling pathway (19). Our previous studies demonstrated that the inhibition of FasL-Fas signaling due to either FasL gene deficiency, delayed (12 h post-CLP) treatment with FasL binding protein (FasFP) or siRNA silencing of Fas not only protected some immune cell populations from apoptosis, but also reduced the morbidity and mortality seen in sepsis (9, 19, 20). However, the basis for the cross talk between Fas-mediated and mitochondrial driven apoptosis during sepsis remains largely unclear. While much is known about the action of Bid in various cell lines or death receptor-induced mortality/liver injury models, its role in immune versus non-immune cell apoptosis as seen in sepsis is less well characterized. Therefore, in the current study, we examined the impact of Bid protein activation on sepsis-induced mortality, apoptosis and inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The studies described here were carried out according to the National Institute of Health Guide for the care and use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital Committee on Animal Use and Care. Bid deficient mice (Bid−/−, which is generated on a C57BL/6 background) were a gift from the late Dr. Stanley Korsmeyer (17). Fas receptor (lpr, B6.MRL-Tnfrsf6lpr/J) or FasL (gld, B6Smn.C3-Faslgld/J) deficient and the background control C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson’s laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were age (8-10 weeks) and sex (male) matched for all experiments.

Sepsis Model of Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP)

Polymicrobial sepsis was induced in mice with the CLP model as described previously (8). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (Abbott Laboratory, Chicago, IL); their abdomen was shaved and scrubbed with betadine. A midline incision (1.0–1.5 cm) was made below the diaphragm to expose the cecum. The cecum was ligated, punctured twice with a 22-gauge needle and gently compressed to extrude a small amount of fecal content through the punctures. The cecum was returned to the abdomen, and the incision was closed in layers with 6–0 Ethilon suture (ETHICON, INC., Somerville, NJ). The animals then were resuscitated with 1.0 ml of lactated Ringer’s solution by subcutaneous injection. The sham-controls were subjected to the same surgical procedure, i.e., laparotomy and cecal isolation, but the cecum was neither ligated nor punctured. For survival studies, C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice were subjected to CLP and survival was monitored for 10 days.

Sample Preparation

Mice were sacrificed and the thymus, spleen, Peyer’s patches, liver and lung were collected at various time points. Thymocytes and splenocytes were obtained by gently grinding the organs between frosted glass slides according to the methods described previously (22). Contaminating red blood cells were lysed with a hypotonic solution. Cells were then centrifuged, counted (by trypan blue exclusion) and either lysed in lysis buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 5mM EDTA, 150mM NaCl, 10mM Sodium Phosphate, 10mM NaF, 1mM Sodium Orthovanadate, 0.5% TritonX100 and protease inhibitor cocktail) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or used for other analyses. Peyer’s patches, liver and lung samples were homogenized in lysis buffer using a PowerGen 125 homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and centrifuged. Protein content of cell/tissue lysate was determined using the BIO-RAD protein assay reagents (Hercules, CA).

Preparation of Mitochondrial and Cytosolic Fractions

Mitochondria were isolated using the Mitochondrial Fractionation kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) (22). In brief, cells/tissues were collected as described above, washed with PBS, resuspended in cytosolic buffer, incubated and homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer (Wheaton, Millville, NJ) 30–50 strokes on ice. Nuclei and unbroken cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 800xg for 20 minutes at 4 C. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 16,000xg for 20 minutes at 4 C to separate the supernatant (cytosolic fraction) and mitochondrial pellet, which was then washed and resuspended in lysis buffer. Protein content of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions was measured as described above.

Western Blot Analysis

The presence of Bid, tBid, active caspase-3 and active caspase-9 in samples was assessed by Western blot as previously described (22). In brief, samples were boiled, separated on 16% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and transferred to Polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Novex, San Diego, CA). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and incubated with anti-mouse Bid and tBid (MAB860, R & D System, Minneapolis, MN), -active caspase-3 (which detects cleaved caspase-3 p17 and p19, but does not recognize full length caspase-3 or other cleaved caspases) (9664S, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) or -active caspase-9 (9509, Cell Signaling) antibodies overnight at 4 C. Membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. After washing, proteins were visualized by ECL and densitometrically assessed by Alpha-Innotech image analyzer. VDAC1 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) was used as a mitochondrial loading control and β-Actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used as a cytosolic loading control.

Assessment of Apoptosis

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Thymocytes and splenocytes were stained with propidium iodide (0.1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium citrate and 50mg/mL PI; Sigma) or TUNEL reagent (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescin, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and analyzed by BD FACSArray Bioanalyzer (22).

Microscopic Examination of Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E), TUNEL or Active Caspase-3 Tissue Section Staining

The thymus, spleen, lung, liver and Peyer’s patches were excised and fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde, and paraffin embedded tissue sections were prepared. H & E staining was performed by Core Research Laboratories at Rhode Island Hospital. TUNEL staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). Active caspase-3 was detected by immunohistochemical staining as described previously (23). In brief, paraffin- embedded tissue slides were dewaxed, rehydrated and incubated with 3% H2O2 in PBS to block endogenous peroxidase followed by non-specific blocking with 5% normal goat serum. After blocking, the slides were incubated with the anti-active-caspase-3 antibody, washed, incubated with a biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit antibody (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), followed by a streptavidin-biotin peroxidase (Sigma). Chromogenic peroxidase substrate, metal enhanced diaminobenzidine (Pierce, Rockford, IL), was added to visualize active caspase-3 staining. Methyl green was used to counter-stain nuclei. The slides were examined under a light or fluorescent microscope for evidence of apoptosis by blinded observers. Image processing and analysis for TUNEL and caspase-3 staining was performed using iVision (BioVision Technologies, Exton, PA). Positive staining was expressed as percent area stained over total area (% area stained).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The thymus, spleen and liver were excised, submerged in half-strength Karnovsky’s fixative in 0.15M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4oC and immediately prepared into 1mm3 blocks and allowed to fix overnight. After fixation, the tissue was washed and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) for 1 hour at 4oC. Following post-fixation, samples were rinsed and dehydrated in a graded series of acetone and embedded in Spurr’s epoxy resin. Semi-thin sections (1 μm) were prepared using a Reichert Ultracut S microtome, stained with methylene blue-azure II and evaluated for areas of interest. Ultra-thin sections (50– 60 nm) were then prepared, retrieved onto 300 mesh copper grids, and contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were examined using a Morgagni 268 transmission electron microscope and images were collected with an AMT Advantage 542 CCD camera system.

Quantification of Cytokine/Chemokine Levels in Plasma or Peritoneal Fluids and Liver Enzyme-ALT in Plasma

Blood was collected in heparinized syringes by cardiac puncture and plasma was obtained by centrifugation and stored at −70 °C until analyzed. Peritoneal fluids were obtained from mice by lavage, clarified by centrifugation and stored at −70 °C as previously described (20). Mouse TNF-α , MCP-1, IL-6 and IL-10 levels were determined in plasma or peritoneal fluids using cytometric bead array technique (BD Cytometric Bead Array Mouse Inflammation Kit, BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (23). In brief, 50 μl of Mouse Inflammation Capture Bead Suspension and 50 μl phycoerythrin-labeled Detection Reagent were added to an equal amount of sample or standard dilution and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature in the dark. Samples were washed with wash buffer and centrifuged at 200xg at room temperature for 5 minutes. Supernatant was discarded; samples were resuspended in wash buffer and analyzed on a BD FACSArray bioanalyzer. Plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), as an index of liver injury, were determined using an assay kit (Pointe Scientific, Inc., Canton, MI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Presentation of Data and Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as a mean ± SEM for each group. Mann-Whittney U-test was used to analyze the comparison between 2 groups. For data comparing more than 2 groups, a one-way ANOVA was executed followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test to determine the differences. The survival data were compared using the Logrank survival analysis. P 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Bid is activated/cleaved and tBid is translocated from the cytosol to the mitochondria after the onset of sepsis

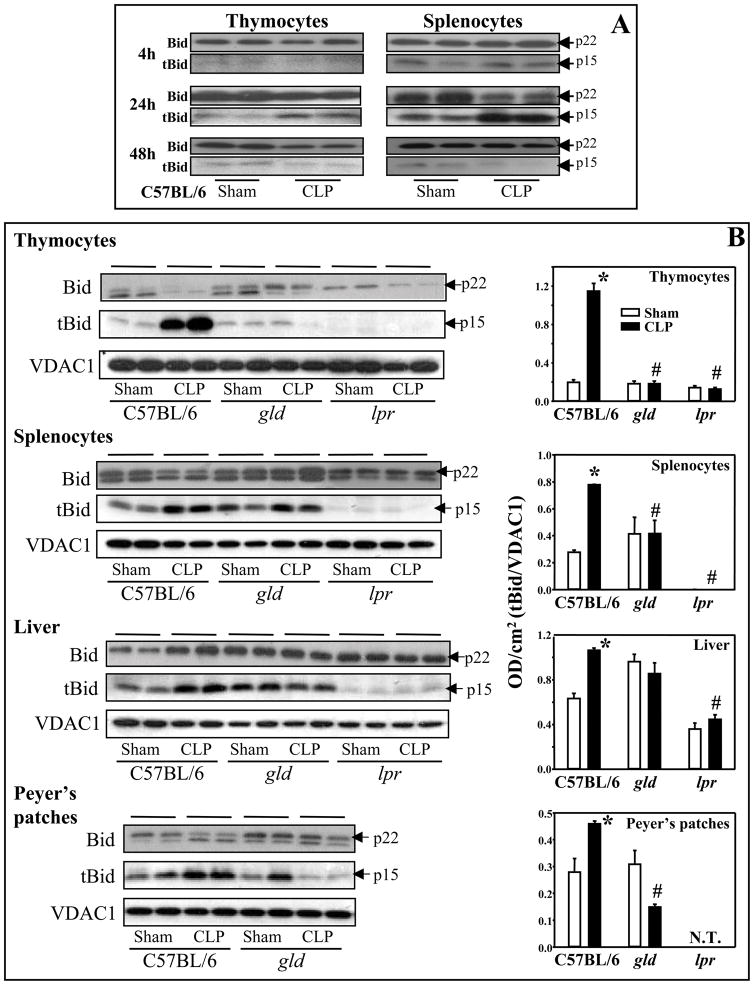

It has been clearly documented that upon activation, cytosolic full length Bid is cleaved into truncated-Bid (tBid) by active caspase-8 (16). tBid translocates to the mitochondrial membrane and activates the caspase-mediated apoptotic cascade. To verify that there was activation of Bid after the onset of sepsis, we initially did a time course using thymocytes and splenocytes. C57BL/6 mice were subjected to sham or CLP procedures, and cells were harvested 4, 24 and 48 hours post-surgery for assessment of Bid (cytosolic fractions) and tBid (mitochondrial fractions) by immunoblottting. At 4 hours post-CLP, tBid was detected in splenocytes (no difference was observed between sham and septic mice), but not in thymocytes. tBid expression peaked at 24 hours and was barely detectable at 48 hours after CLP in both sites (Fig. 1A). Based on these data, 24 hours was chosen for assessment in most of the subsequent experiments. We observed that in C57BL/6 mice, polymicrobial sepsis induced an increase in activation of Bid and translocation of tBid from the cytoplasm to mitochondria in Peyer’s patches and liver as well as the thymocytes and splenocytes, but not in the lung, when compared with sham controls at 24 hours post-CLP (Fig. 1B). Since Bid has been identified as a critical protein in connecting the death receptor (Fas, TNF receptor 1, etc.) and mitochondrial death pathways, and as our laboratory has previously shown the signaling through the Fas/FasL pathway contributes to septic morbidity/mortality (9, 19, 20), we investigated the effects of Fas-mediated pathway on Bid activation after septic challenge. Bid and tBid were determined by immunoblotting of cells/tissues taken from Fas−/− (lpr) or FasL−/− (gld) mice 24 hours after surgery. Interestingly, it appears that when the Fas-FasL pathway is disrupted through Fas or FasL deficiency, the activation of Bid is differentially affected in various tissues taken from lpr or gld mice (Fig. 1B). Our results show that not only was Bid activation after sepsis diminished in thymocytes, splenocytes and the livers of lpr mice as compared with C57BL/6 CLP mice, but this activation in lpr sham animals was also reduced as compared with C57BL/6 sham mice. In gld mice, septic insult did not lead to an increase in Bid activation/translocation in all cells/tissues tested as seen in C57BL/6 CLP mice. However, unlike lpr mice, the basal mitochondrial levels of tBid in gld sham and CLP animals were generally comparable to C57BL/6 shams, with the exception of the liver where tBid activation in both gld sham and CLP mice was comparable to C57BL/6 CLP mice (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Sepsis-induced changes in Bid activation and tBid translocation from cytosol to mitochondria that the activation was differentially affected by blockade of Fas-FasL signaling. A, C57BL/6 mice were subjected to sham or CLP. Thymocytes and splenocytes were harvested at 4, 24, and 48 hours after surgery. The extent of total Bid (p22) in cytosolic fractions and tBid (p15) protein in the mitochondrial fractions were determined by Western blot analyses. B, C57BL/6 background, gld or lpr mice were subjected to sham or CLP, and 24 hours later, thymocytes, splenocytes, liver and Peyer’s patches were harvested. The extent of total Bid and tBid were determined by Western blot analyses (left panels) and semi-quantitated by densitometry and expressed as integrated density (IDT) values of tBid relative to IDT values of VDAC1 (right panels). *, P<0.05, versus respective sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=4–8 mice/group. N.T., not tested.

Bid deficiency reduces septic mortality

To determine whether deficiency of pro-apoptotic Bid protein could provide protection against septic mortality, C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice were subjected to CLP and their survival was monitored for 10 days (Fig. 2). The survival rate for the C57BL/6 background mice steadily declined over the 1st 7 days to ~30%. This was significantly different from the Bid−/− mice, which exhibited slower mortality that resulted in a survival rate of ~78% from day 4 until day 10.

Figure 2.

Bid deficiency improved survival following sepsis. C57BL/6 background and Bid deficient mice were subjected to CLP and ten-day survival was recorded. Bid−/− mice showed an improvement in survival when compared with C57BL/6 background mice and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05, Logrank survival analysis; n=13–17 mice/group).

Bid deficiency reduces sepsis-induced apoptosis in different cells/tissues

To compare the extent of sepsis-induced apoptosis between C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice, several methods were used. Flow cytometric assessment of apoptotic DNA fragmentation was performed using the DNA binding agent propidium iodide and TUNEL staining. A significant increase in apoptosis of thymocytes and splenocytes was observed in both the septic C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice when compared with their respective shams at 24 hours post-CLP (Fig. 3). However, the extent of apoptosis in cells taken from septic Bid−/− mice was significantly lower than that from septic C57BL/6 mice. In addition to DNA analysis, increased active capsase-3 was detected by Western blot analysis, verifying the increased apoptosis in these cells. The results also show that Bid deficiency reduced caspase-3 activation in the spleen, thymus and Peyer’s patches 24 hours after sepsis (Fig. 4A). Additionally, we examined the kinetics of caspase-3 activation in thymocytes and splenocytes at 4 and 48 hours post-CLP in the C57BL/6 mice. Figure 4B shows an increase in active caspase-3 in thymocytes but no changes in splenocytes when compared with shams 4 hours after sepsis. Similar to Bid activation, active caspase-3 levels peaked at 24 hours and diminished to lower than sham controls 48 hours after CLP. These results suggest that the kinetics of caspase-3 activation is slightly different between thymocytes and splenocytes during sepsis; however, both cell types showed a peak of caspase-3 activation at 24 hours post-CLP. Since caspase-9 is the central initiator caspase of the intrinsic death pathway, we also determined whether the activation of caspase-9 was affected by Bid deficiency after sepsis. Immunoblot results demonstrated that while active caspase-9 was increased 24 hours after sepsis in C57BL/6 background mice, no such increase was observed in the spleen and thymus of septic Bid−/− mice (Fig. 5). Alternatively, caspase-9 was equally activated in the septic livers of both C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Bid deficiency reduced sepsis-induced apoptosis in thymocytes and splenocytes. Cells were isolated from C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice 24 hours after subjected to sham or CLP procedures. Apoptosis was determined by terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay or Propidium Iodide (PI) staining. A decreased apoptosis in thymocytes (A) and splenocytes (B) taken from Bid−/− mice after sepsis was observed when compared with C57BL/6 background mice. *, P<0.05, versus respective sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=4-8 mice/group.

Figure 4.

Active caspase-3 levels in Bid−/− mice were reduced after sepsis. A, thymocytes, splenocytes and Peyer’s patches were collected from C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice 24 hours after subjected to sham or CLP procedures. Active caspase-3 (p17/p19) was determined by Western blot analyses (left panels) and semi-quantitated by densitometry, expressed as integrated density (IDT) values of tBid relative to IDT values of β-Actin (right panels). B, Kinetics of caspase-3 activation in C57BL/6 mice after CLP. *, P<0.05, versus respective sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=4-8 mice/group.

Figure 5.

Deficiency of Bid reduced active caspase-9 levels in thymocytes and splenocytes after sepsis. Thymocytes, splenocytes and the liver were harvested from C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice 24 hours after subjected to sham or CLP procedures. Activate caspase-9 was determined by Western blot analyses (left panels) and semi-quantitated by densitometry, expressed as integrated density (IDT) values of tBid relative to IDT values of β-Actin (right panels). *, P<0.05, versus respective sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman- Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=4-8 mice/group.

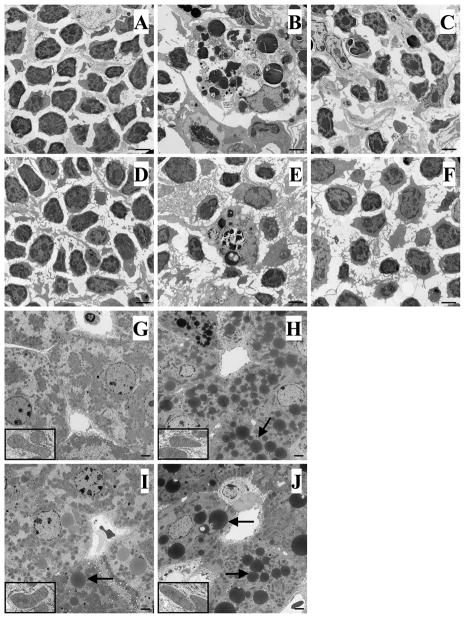

To further confirm that the results observed in the isolated cells/tissues was representative of in vivo changes at the tissue level, we sought morphologic evidence of apoptosis in the thymus, spleen, Peyer’s patch and liver using light and electron microscopy. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate typical light microscopic pictures of H & E-stained tissue sections and electron micrographs, respectively. A marked increase in apoptotic cells, characterized by cell shrinkage, pyknosis and deformation of the cell membrane, was seen in the thymus (Fig. 6B, 7B [C57BL/6] & 6C, 7C [Bid−/−]), spleen (Fig. 6E, 7E [C57BL/6] & 6F, 7F [Bid−/−]) and Peyer’s patches (Fig. 6H [C57BL/6] & 6I [Bid−/−]) taken from C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice at 24 hours after sepsis as compared with shams (note: since there was no difference between C57BL/6 and Bid−/− shams, one set of sham was used as representative in figures 6, 7, 8 and 9). However, these types of morphological changes were much less evident in septic Bid−/− mice (Fig. 6C, 6F, 6I & 7C, 7F) compared with septic C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 6B, 6E, 6H & 7B, 7E). Interestingly, in the liver, the electron micrographs indicated relatively normal mitochondrial morphology (see insets) and minimum signs of overt apoptosis after sepsis in either mouse strain (Fig. 7H [C57BL/6], 7J [Bid−/−]) compared with their respective shams (Fig. 7G [C57BL/6], 7I [Bid−/−]). The most apparent finding was a loss of glycogen stores and a substantial increase in lipid-like vesicles (which may be related to sepsis-induced steatosis or fatty change often seen in patients) encountered in the hepatocytes of both septic C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice. Of note, while less obvious compared with the septic mouse hepatocytes, the Bid−/− sham mice appear to have more of these lipid-like droplets than the background shams (Fig. 7G, 7I). This could be associated with the unexpected role of tBid in transfer and recycling of mitochondrial phospholipids (24) and in the regulation of lipid beta-oxidation (25).

Figure 6.

Representative H&E staining of tissue sections for detection of apoptosis by morphology examined under light microscopy. C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice were subjected to sham or CLP procedures and 24 hours later paraffin embedded tissue sections were prepared. Sham animals (C57BL/6 and Bid−/−) display normal histology of thymus (A), spleen (D) and Peyer’s patches (G). While septic C57BL/6 mice exhibited typical apoptotic morphology (Arrows) in all three tissues (B, thymus; E, spleen; H, Peyer’s patches) when compared with sham–operated mice, Bid deficient animals showed fewer apoptotic cells in these tissues after sepsis (C, thymus; F, spleen; I, Peyer’s patches). Original magnifications, X 400.

Figure 7.

Representative electron micrographs of tissue sections for morphological detection of apoptosis. C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice were subjected to sham or CLP procedures and 24 hours later tissue sections were prepared for electron microscopy. Sham animals (C57BL/6 and Bid−/−) display normal histology of thymus (A) and spleen (D). While septic C57BL/6 mice exhibited a typically cluster of apoptotic cells in these tissues (B, thymus; E, spleen) when compared with sham– operated mice, Bid deficient animals showed fewer apoptotic cells after sepsis (C, thymus; F, spleen). Original magnification, 4400X. In the liver, the electron micrographs showed relatively normal mitochondria (inset, original magnification, 5540X) and minimum signs of apoptosis after sepsis in either C57BL/6 (H) or Bid−/− (J) mice compared with their shams (G, C57BL/6; I, Bid−/−). However, Bid−/− mice appear to have more of the lipid-like droplets (Arrows) (I, sham; J, CLP). Original magnification, 2800X.

Figure 8.

Representative immunohistochemical staining of active caspase-3 in tissue sections. C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice were subjected to sham or CLP procedures and 24 hours later paraffin embedded tissue sections were prepared and stained with anti-caspase-3. Sham animals display no or slight staining of active caspase-3 in the thymus (A), spleen (D) and Peyer’s patches (G). While septic C57BL/6 mice exhibited extensive active caspase-3 staining (Arrows) in all three tissues (B, thymus; E, spleen; H, Peyer’s patches) when compared with sham–operated mice, Bid deficient animals showed less staining in these tissues after sepsis (C, thymus; F, spleen; I, Peyer’s patches). Original magnifications, X 400. Quantification of the images was processed and analyzed using iVision software. Positive staining was defined through thresholding, the resulting images were analyzed, and data were expressed as percent area stained over total area (% area stained). *, P<0.05, versus sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=3/group.

Figure 9.

Representative immunohistochemical TUNEL staining in tissue sections. C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice were subjected to sham or CLP procedures and 24 hours later paraffin embedded tissue sections were prepared and stained with TUNEL. Sham animals display no or slight staining of TUNEL in thymus (A) and spleen (D). While septic C57BL/6 mice exhibited extensive a typical apoptotic morphology in tissues (B, thymus; E, spleen) when compared with sham–operated mice, Bid deficient animals showed less TUNEL staining in these tissues after sepsis (C, thymus; F, spleen). Original magnifications, X 400. Quantification of the images was processed and analyzed using iVision software. Positive staining was defined through thresholding, the resulting images were analyzed, and data were expressed as percent area stained over total area (% area stained). *, P<0.05, versus sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=3/group.

Immuno-histochemical staining for active caspase-3 (Fig. 8) and TUNEL (Fig. 9) were also performed to further assess the extent of apoptosis. We observed results consistent with the earlier morphologic assessment. A substantial increase in active caspase-3 (thymus, spleen and Peyer’s patches) and TUNEL (thymus and spleen) staining were observed in both C57BL/6 (Fig. 8B, 8E, 8H and Fig. 9B, 9E) and Bid−/− (Fig. 8C, 8F, 8I and Fig. 9C, 9F) mice 24 hours after the induction of sepsis as compared with shams (Fig. 8A, 8D, 8G and Fig. 9A, 9D). However, Bid−/−mice had a reduction in sepsis-induced apoptosis in the tissues tested. As seen with H & E staining, we did not observe obvious changes in active caspase-3 or TUNEL staining in the liver (data not shown). Additionally, while we found that sepsis induced a significant elevation in plasma levels of the liver enzyme ALT in C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice when compared with their respective shams, ALT levels were not different between the septic mice of both strains (C57BL/6 Sham: 8.7 ± 2.3 IU/mL; C57BL/6 CLP: 35.6 ± 6.7 IU/mL; Bid−/− Sham: 10.6 ± 2.8 IU/mL; Bid−/− CLP: 45.7 ± 16.1 IU/mL). This suggests that other mechanisms (necrotic death and/or autophagy) could contribute to cell death in the liver in our model of sepsis.

Bid deficiency reduces sepsis-induced systemic and local pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines

Plasma cytokines/chemokines were measured in sham and septic mice 12 and 24 hours after surgery. Plasma levels of TNF-α , MCP-1, IL-10 and IL-6 were markedly increased in C57BL/6 mice 12 (Fig. 10A & B) and 24 hours (Fig. 10C & D) after the onset of sepsis compared with sham mice. However, Bid−/− mice did not respond to septic challenge as vigorously as C57BL/6 mice. At 12 hours after CLP, while plasma levels of TNF-α , MCP-1 and IL-6 (but not IL-10) in Bid−/− septic mice were significantly elevated compared with their shams, IL-6 and IL-10 levels were markedly lower and TNF-α and MCP-1 were slightly lower than C57BL/6 septic mice. By 24 hours after CLP, all four cytokine levels in plasma of Bid−/− mice were significantly lower compared with C57BL/6 mice. Likewise, Bid deficiency reduced local cytokine/chemokine production in the peritoneal cavity of septic mice. MCP-1 and IL-10 levels at 12 hours (Fig. 10E & F) and TNF-α , MCP-1 and IL-10 levels at 24 hours (Fig. 10G & H) in peritoneal fluids from Bid−/− septic mice were significantly lower than those in septic C57BL/6 mice.

Figure 10.

Cytokine/chemokine levels in plasma (circulation) and peritoneal cavity (local). C57BL/6 background or Bid−/− mice were subjected to sham or CLP procedures; 12 and 24 hours later, plasma and peritoneal fluid were collected for measurement of cytokine/chemokine concentration (pg/mL) by cytometric bead array. Plasma levels of TNF-α , MCP-1, IL-10 and IL-6 were significantly increased in septic C57BL/6 mice at 12 (A, B) and 24 (C, D) hours compared with their shams. Although TNF-α , MCP-1 and IL-6 at 12 hours and MCP-1 and IL-6 at 24 hours in septic Bid−/− mice were also increased compared with shams, these plasma cytokine/chemokine levels were significantly decreased compared with C57BL/6 mice at 24 hours and to a lesser extent at 12 hours after CLP. Bid deficiency also reduced local cytokine/chemokine production in the peritoneal cavity after CLP. MCP-1 and IL-10 levels at 12 hours (E, F) and TNF-α , MCP-1 and IL-10 levels at 24 hours (G, H) in peritoneal fluids from Bid−/− septic mice were significantly lower than those in septic C57BL/6 mice. *, P<0.05, versus respective sham; #, P<0.05, versus C57BL/6 CLP. One-way ANOVA and a Student-Newman-Keuls’ test, Mean ± SEM; n=6-8 mice/group.

DISCUSSION

Many studies, including experimental animal and clinical studies, have demonstrated that apoptotic cell death via either the death receptor or mitochondrial pathway plays a critical role in sepsis (4, 19–21). However, the function of BH3-only, pro-apoptotic protein Bid, which is thought to be a key protein connecting the extrinsic to the intrinsic cell death pathway, in sepsis-induced apoptosis has not been clearly defined. In the current study, we examined the contribution of Bid protein to apoptosis in several tissues, its impact on mortality, and its effect on inflammation in response to a polymicrobial septic challenge (CLP) in mice.

While much is known about the action of Bid in various cell lines and acute death receptor-induced mortality/liver injury (17, 18, 26), its role in sepsis is less well characterized. A recent clinical study demonstrated that gene expression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, including Bim and Bid, was up-regulated and anti-apoptotic members were down-regulated in the peripheral blood from patients with severe sepsis (27). However, due to the nature of such observational clinical data, whether Bid gene expression in these patient samples contributed to sepsis pathology could not be determined.

To investigate the involvement of Bid in the increased apoptosis as seen in sepsis, we initially compared the changes in Bid activation in several organs taken from sham or septic C57BL/6 mice at 4, 24 and 48 hours after procedures. Our results demonstrated that there is a significant increase in Bid cleavage/activation (tBid) and translocation of tBid to mitochondria of cells within the thymus, spleen, Peyer’s patches and liver 24 hours after the onset of polymicrobial sepsis induced by CLP. Since Bid is a unique BH3-only member and is thought to be required for the connection of extrinsic cell death initiated by the Fas-FasL pathway and the activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, we chose to utilize lpr (Fas deficient) or gld (FasL deficient) mice to examine the effects of Fas-FasL signaling on Bid activation during sepsis. We found that inhibition of the Fas-FasL pathway did affect Bid activation during sepsis. The activation of Bid was completely blocked after septic insult, as indicated by its translocation to the mitochondria in all tissues assessed from sham or CLP lpr mice when compared with C57BL/6 wild type mice. However, the degree of Bid activation in gld mice appeared to be somewhat more tissue dependent. While Bid activation due to CLP was still blunted in the thymus, spleen and Peyer’s patches taken from gld mice, we observed higher basal levels, equivalent to C57BL/6 sham level, of tBid in both sham and CLP mice. Interestingly, Bid activation in the liver of both gld sham and CLP mice was as high as septic C57BL/6 mice. These results suggest that FasL-independent pathways of basal Bid activation may exist in the liver. There are, however, other possible explanations: 1) In the absence of having a functional FasL protein, compensatory mechanisms involving other death receptor ligands are upregulated to account for this higher basal mitochondrial level of tBid; or 2) It is also possible that besides caspase-8, there are other proteases activated during sepsis including caspase-2, caspase-3, caspase-10 or granzyme B, which may serve to cleave/activate Bid as well (28).

As a pathologic index of sepsis, apoptosis has been observed in septic patients and experimental animals (4, 19–21). Using the CLP model of sepsis, we found that deletion of the Bid gene significantly reduced apoptosis in the spleen, thymus and Peyer’s patches, but this was less evident in the lung and liver. From our past experiences, sepsis produced by CLP had minimal effects on lung function (29); therefore, we did not anticipate finding substantial changes in lung tissue apoptosis 24 hours after CLP. However, other studies have indicated that Bid deficiency ameliorated lung injury and provided early protection from mortality in a mouse model of endotoxemia (30), suggesting a role for Bid in lung cell apoptosis. Unfortunately, while endotoxic shock is an excellent model of acute inflammatory and/or toxic shock, it is not considered by many to be an adequate model of sepsis as the levels of endotoxin utilized are substantially higher than those encountered in CLP or in septic patients (see review in (5)). With respect to the liver, neither background nor Bid−/− mice had obvious evidence of apoptosis histologically (light or electron microscopy) after sepsis, even though tBid translocation to the mitochondria was increased in the livers of septic background C57BL/6 mice. In fact, the livers taken from septic Bid−/− mice exhibited similar levels of active caspase-9 and more lipid-like droplets in electron micrographs when compared with septic C57BL/6 mice. The reason for this is not clear; however, this is possibly due to the activation of diverse downstream signaling pathways. It appears that Bid is essential for hepatocyte apoptosis. Deletion of Bid has been shown to result in an effective blockade of Fas-mediated hepatocyte apoptosis, liver damage, and mortality using an agonist anti-Fas antibody (Jo2) treatment in vivo (17). Nearly 90% of wild type mice die within 4 hours in this acute model of liver injury. However, the same laboratory also demonstrated that although Bid deficient mice were significantly more resistant to TNF-α - mediated (an alternative death receptor activator) liver injury and lethality, it only temporarily delayed hepatocyte cell death, liver injury and mortality (8 hours as compared with 4 hours) (26). Hence, sepsis induced by CLP, which is a complex stimulus, affects most of the organs and activates numerous biological responses and mediators that might affect the apparent actions of Bid on apoptosis as it occurs in various tissues/organs. We noted that after CLP, Bid deficiency only partially suppressed apoptosis in various tissues. This is not unexpected as Bid-independent mitochondrial activation can also be induced by other mechanisms including reactive oxygen species accumulation, JNK activation (31) and reactive oxygen species-induced mitochondrial permeability transition (32). Unlike the anti-Fas-induced liver injury model, Bid deficiency appears to have less effect on the liver in our model of sepsis induced by CLP. Despite the lack of morphological evidence of obvious apoptotic cell death in the liver after sepsis in both mouse strains, we observed elevated plasma levels of ALT, an index of liver injury, in both septic C57BL/6 and Bid−/− mice. This suggests that other cell death mechanisms (necrotic death and/or autophagy) may be involved in sepsis-induced liver injury. Conversely, the decrease in sepsis-induced apoptosis in Bid−/− mice was evident mainly in lymphoid organs such as thymus, spleen and Peyers’ patches, and less overt in non-lymphoid tissues such as the lung or liver. Interestingly, previous studies from our laboratory have documented that sepsis-induced thymocyte apoptosis is steroid driven and is not dependent on endotoxin, TNF-α or Fas pathways (33). We believe that the observation of reduced thymus apoptosis in septic Bid−/− mice is likely not related to Fas activation. Indeed, studies have shown that glucocorticoid, which increases during stress/injury, can induce the cleavage/activation of Bid in cultured lymphocytes(34) and eosinophils (35). tBid can then activate the mitochondrial death pathway and induce steroid-mediated apoptosis in leukocytes.

As mentioned previously, many animal studies have shown that overexpression of anti-apoptotic or deletion/knock down of pro-apoptotic genes can improve septic survival. Our previous studies also indicate that blocking Fas-FasL signaling using Fas fusion protein or Fas siRNA reduced septic mortality (9, 19, 20). In agreement with these studies, reduced apoptosis is associated with an improved survival rate in Bid −/− mice subjected to CLP, indicating that Bid protein plays an important role in sepsis-induced apoptosis and mortality. This is supported by a recent report by Chang, et al. (36) in which an increased survival rate was observed in Bid−/− mice after CLP.

Septic mortality is thought to be closely related to the development of a systemic inflammatory response. Dysregulation of the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance has been postulated to play an important role in the outcome of sepsis (37). In this regard, our present data indicates that Bid deficiency reduced inflammation not only systemically, but also locally. While plasma levels of cytokine/chemokine (TNF-α , IL-6, IL-10 and MCP-1) were significantly elevated in C57BL/6 mice at 12 and 24 hours after sepsis, Bid deficiency markedly reduced these circulating cytokine/chemokine levels especially at 24 hours post-CLP. Similarly, these cytokine/chemokine levels in the local peritoneal cavity were also significantly reduced in Bid−/− mice after insult, with the exception of IL-6. However, the sources and mechanisms behind the release of these mediators and how Bid protein regulates the inhibition by Bid−/− are not clear.

In addition to its initially characterized pro-apoptotic role, Bid protein may also be involved in other cellular functions. Studies have indicated that Bid may play a role in promoting hepatocarcinogenesis (38) and DNA damage-induced or replicative stress-induced apoptosis or cell cycle arrest (39), although Kaufmann et al. have reported that Bid protein does not function in the DNA damage response (40). Bid has also been shown to be required for maintenance of myeloid homeostasis and suppression of myeloid tumorigenesis (41). Moreover, Bid appears to be essential for the resolution of inflammation in a mouse model of arthritis, as Bid deficiency prolonged joint inflammation and delayed the resolution of arthritis (42). The significance of these divergent functions of Bid remains open to debate and needs more investigation to broaden our understanding of this protein.

In summary, our findings indicate that sepsis induces Bid activation and translocation of tBid from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria. Bid deficiency rescues mice from septic mortality, and this is associated with reduced apoptosis in lymphoid organs as well as the suppression of local and systemic cytokine/chemokine levels during sepsis. BH3 domain-only proteins can regulate Bcl-2 proteins by neutralizing (depressing) anti-apoptotic proteins, activating pro-apoptotic proteins, or directly binding and activating Bax/Bak to induce apoptosis (43). These BH3-only proteins appear to be critical to mediating the cell death program and thus, understanding their function will be important to identify how the induction of apoptosis contributes to septic mortality, which may provide insight into a novel therapeutic target for management of this condition.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH project grants GM53209-10. The authors would like to thank Mr. Paul Monfils and Ms. Virginia Hovanesian, Core Research Laboratories, Rhode Island Hospital, for assistance with histology and imagine analysis.

Contributor Information

Chun-Shiang Chung, Division of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

Fabienne Venet, Division of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

Yaping Chen, Division of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

Leslie N Jones, Division of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

Douglas C Wilson, Department of Pathobiology, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

Carol A Ayala, Core Research Lab, Rhode Island Hospital, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

Alfred Ayala, Division of Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Brown University, Providence RI 02903.

References

- 1.Smith JA. Neutrophils, host defense, and inflammation: a double-edged sword. J Leukocyte Biol. 1994;56:672–686. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.6.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson CB. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science. 1995;267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann KC, Bonzon C, Green DR. The machinery of programmed cell death. Pharmac Ther. 2001;92:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–1251. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayala A, Chung CS, Chaudry IH. Lymphocyte apoptosis in sepsis. Sepsis. 1998;2:55–71. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotchkiss RS, Chang KC, Swanson PE, Tinsley KW, Hui JJ, Klender P, Xanthoudakis S, Roy S, Black C, Grimm E, Aspiotis R, Han Y, Nicholson DW, Karl IE. Caspase inhibitors improve survival in sepsis: a critical role of the lymphocyte. Nature Immunol. 2000;1:496–501. doi: 10.1038/82741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberholzer C, Oberholzer A, Bahjat FR, Minter RM, Tannahill CL, Abouhamze A, LaFace D, Hutchins B, Clare-Salzler MJ, Moldawer LL. Targeted adenovirus-induced expression of IL-10 decreases thymic apoptosis and improves survival in murine sepsis. PNAS. 2001;98:11503–11508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181338198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung CS, Xu YX, Wang W, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Is Fas ligand or endotoxin responsible for mucosal lymphocyte apoptosis in sepsis? Arch Surg. 1998;133:1213–1220. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.11.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wesche DE, Chung CS, Lomas-Neira J, Doughty LA, Gregory SH, Ayala A. In vivo delivery of caspase 8 or Fas siRNA improves the survival of septic mice. Blood. 2005;106:2295–2301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Knudson CM, Chang KC, Cobb JP, Osborne DF, Zollner KM, Buchman TG, Korsmeyer SJ, Karl IE. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice decreases apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. J Immunol. 1999;162:4148–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung CS, Watkins L, Funches A, Lomas-Neira JL, Cioffi WG, Ayala A. Deficiency of gamma-delta T-lymphocytes contributes to mortality and immunosuppression in sepsis. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:1338–1343. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00283.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorburn A. Death receptor-induced cell killing. Cellular Signalling. 2004;16:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borner C. The Bcl-2 protein family: sensors and checkpoints for life-or-death decisions. Mol Immunol. 2003;39:615–647. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, Friesen C, Li F, Tomaselli KJ, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strasser A, Harris AW, Huang DCS, Krammer PH, Cory S. Bcl-2 and Fas/APO-1 regulate distinct pathways to lymphocyte apoptosis. EMBO J. 1995;14:6136–6147. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Zhu H, Xu C, Yuan J. Cleavage of BID by Caspase 8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell. 1998;94:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin X-M, Wang K, Gross A, Zhao Y, Zinkel S, Klocke B, Roth KA, Korsmeyer SJ. Bid-deficient mice are resistant to Fas-induced hepatocellular apoptosis. Nature. 1999;400:886–891. doi: 10.1038/23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Yin X-M, Gores GJ. Bid is upstream of lysosome-mediated caspase 2 activation in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced hepatocyte apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:269–284. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung CS, Yang SL, Song GY, Lomas J, Wang P, Simms HH, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Inhibition of Fas signaling prevents hepatic injury and improves organ blood flow during sepsis. Surgery. 2001;130:339–345. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung CS, Song GY, Lomas J, Simms HH, Chaudry IH, Ayala A. Inhibition of Fas/Fas ligand signaling improves septic survival: differential effects on macrophage apoptotic and functional capacity. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:344–351. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0102006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hotchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:813–822. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung CS, Chen YP, Grutkoski PS, Doughty LA, Ayala A. SOCS-1 is a central mediator of steroid-increased thymocyte apoptosis and decreased survival following sepsis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1143–1153. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perl M, Chung CS, Lomas-Neira J, Rachel TM, Biffl WL, Cioffi WG, Ayala A. Silencing of Fas- but not caspase-8 in lung epithelial cells ameliorates pulmonary apoptosis, inflammation, and neutrophil influx after hemorrhagic shock and sepsis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1545–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esposti MD, Erler JT, Hickman JA, Dive C. Bid, a widely expressed proapoptotic protein of Bcl-2 family, displays lipid transfer activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7268–7276. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7268-7276.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giordano A, Calvani M, Petillo O, Grippo P, Tuccillo F, Melone MA, Bonelli P, Calarco A, Peluso G. tBid induces alterations of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation flux by malonyl-CoA-independent inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2005;12:603–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Ding W-X, Ni H-M, Gao W, Shi Y-H, Gambotto AA, Fan J, Beg AA, Yin X-M. Bid-independent mitochondrial activation in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis and liver injury. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:541–553. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01166-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuber F, Weber SU, Schewe JC, Lehmann LE, Muller S, Book M, Klaschik S, Stuber Induction of Bim and Bid gene expression during accelerated apoptosis in severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2008;12:R128. doi: 10.1186/cc7088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin X-M. Bid, a BH3-only multi-functional mlecule, is at the cross road of life and death. Gene. 2006;369:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayala A, Chung CS, Lomas J, Song GY, Doughty LA, Gregory SH, Cioffi WG, LeBlanc BW, Reichner J, Simms HH, Grutkoski PS. Shock-induced PMN mediated priming for acute lung injury in mice: divergent effects of TLR-4 and TLR-4/FasL deficiency. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2283–2294. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64504-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang HL, Akinci IO, Baker CM, Urich D, Bellmeyer A, Jain M, Chandel NS, Mutlu GM, Budinger GRS. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is required for lipopolysaccharide-induced lung endothelial cell death. J Immulogy. 2007;179:1834–1841. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Smaele E, Zazzeroni F, Papa S, Nguyen DU, Jin R, Jones J, Cong R, Franzoso G. Induction of gadd45β by NF-κB downregulates pro-apoptptic JNK signaling. Nature. 2001;414:308–313. doi: 10.1038/35104560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y, Ding WX, Qian T, Watkins S, Lemasters JJ, Yin X-M. Bid activates multiple mitochondrial apoptotic mechanisms in primary hepatocytes after death receptor engagement. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:854–867. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayala A, Xu YX, Chung CS, Chaudry IH. Does Fas ligand or endotoxin contribute to thymic apoptosis during polymicrobial sepsis? Shock. 1999;11:211–217. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199903000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Planey SL, Derfoul A, Steplewski A, Robertson NM. Inhibition of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in 697 pre-B lymphocytes by the mineralocorticoid receptor N-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42188–42196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segal M, Niazi S, Simons MP, Galati SA, Zanhrilli JG. Bid activation during induction of extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis in eosinophils. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2007;85:518–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang KC, Unsinger J, Davis CG, Schwulst SJ, Muenzer JT, Strasser A, Hotchkiss RS. Multiple triggers of cell death in sepsis: death receptor and mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis. FASEB J. 2007;21:708–719. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6805com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bai L, Ni H-M, Chen X, Difrancesca D, Yin X-M. Deletion of bid impedes cell proliferation and heptic carcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1523–1532. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62368-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinkel SS, Hurov KE, Ong C, Abtahi FM, Gross A, Korsmeyer SJ. A role for proapoptotic BID in the DNA-damage response. Cell. 2005;122:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaufmann T, Tai L, Ekert PG, Huang DCS, Norris F, Lindemann RK, Johnstone RW, Dixit VM, Strasser A. The BH3-only protein Bid is dispensable for DNA damage- and replicative stress-induced apoptosis or cell-cycle arrest. Cell. 2007;129:423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zinkel SS, Ong CC, Ferguson DO, Iwasaki H, Akashi K, Bronson RT, Kutok JL, Alt FW, Korsmeyer SJ. Proapoptotic BID is required for myeloid homeostasis and tumor suppression. Genes & Development. 2008;17:229–239. doi: 10.1101/gad.1045603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scatizzi JC, Hutcheson J, Bickel E, Haines GK, III, Perlman H. Pro-apoptotic Bid is required for the resolution of the effector phase of inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R49. doi: 10.1186/ar2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baskin-Bey ES, Gores GJ. Death by association: BH3 domain-only proteins and liver injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G987–G990. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00371.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]